Abstract

Restoring sleep is strongly associated with a better physical, cognitive, and psychological well-being. By contrast, poor or disordered sleep is related to impairment of cognitive and psychological functioning and worsened physical health. These associations are well documented not only in adults but also in children and adolescents. Importantly, adolescence is hallmarked by dramatic maturational changes in sleep and its neurobiological regulation, hormonal status, and many psychosocial and physical processes. Thus, the role of sleep in mental and physical health during adolescence and in adolescent patients is complex. However, it has so far received little attention. This review first presents contemporary views about the complex neurobiology of sleep and its functions with important implications for adolescence. Second, existing complex relationships between common adolescent somatic/organic, sleep-related, and psychiatric disorders and certain sleep alterations are discussed. It is concluded that poor or altered sleep in adolescent patients may trigger and maintain many psychiatric and physical disorders or combinations of these conditions, which presumably hinder recovery and may cross into later stages of life. Therefore, timely diagnosis and management of sleep problems appear critical for growth and development in adolescent patients.

Introduction

Sleep is a universal biological feature in all species, and represents a global state of immobility with greatly reduced responsiveness to environmental stimuli, which can be distinguished from coma or anesthesia by its rapid reversibility.Citation1–Citation3 It is by no means a dormant state. When prevented from sleeping, the body tries to recover the lost sleep time. Thus, the existence of sleep rebound after deprivation reveals that sleep is not simply a period of reduced activity or alertness regulated by circadian or ultradian rhythms.Citation4 Furthermore, sleep in most vertebrates and all mammal species display a specific architecture and dramatic changes in brain electrophysiology, neurochemistry, and functional anatomy biologically distinguish the different sleep stages from one another.Citation5

Although the precise functions of sleep are still beyond a comprehensive understanding, a large body of data show its critical role in many important somatic, cognitive, and psychological processes. Its vital importance is well documented by the fact that sleep deprivation in rodents and flies can cause death more quickly than food deprivation.Citation6 It is believed that sleep is beneficial for energy conservation and neuronal recuperation,Citation3 synaptic homeostasis,Citation7 and brain plasticity.Citation8,Citation9 For example, sleep is shown to serve many metabolic, immune, thermoregulatory, cardiovascular, and respiratory functions, all responsible for the normal brain and body homeostasis.Citation2,Citation3,Citation7,Citation10, Along with these functions, sleep is shown to play a key role in important cognitive and psychological processes, including learning and offline memory consolidation,Citation8,Citation11 human heuristic creativity and insightfulness,Citation12–Citation15 cognitive abilities,Citation16–Citation21 consolidation of emotional memory,Citation22–Citation24 and emotional processingCitation25–Citation28 including stress-related coping strategies.Citation29 Also, a recent study points to a role for sleep in sustaining the so-called default mode network of the brain during quiet wake, which is important for adequate cognitive processes.Citation30 Collectively, these data emphasize the beneficial effects of restoring sleep on physical, cognitive, and psychological well-being.Citation1 Therefore, sleep is a vital feature, and its situational or pathological alterations can induce maladaptive functioning and a number of psychiatric and physical diseases.

Important maturational sleep alterations in association with changes in many other functions are normally observed during development, with the adolescence being considered an especially vulnerable period during which many physiological, cognitive, and psychological processes sharply mature and are at risk for morbidity. For these reasons, adolescence is drawing increasing attention from broad scientific fields of research. However, the functional importance of sleep in a variety of common conditions during adolescence has so far received less attention.

Adolescence is defined as the period of gradual transition between childhood and adulthood, which are overlapping yet conceptually distinct from the physical changes marking puberty and physical maturation.Citation31,Citation32 It is characterized by drastic changes in hormonal and somatic statusCitation33,Citation34 accompanied by substantial nonlinear changes in brain structural and functional organization and behavior.Citation31,Citation35 For example, during this developmental window many psychological functions such as social brain,Citation36,Citation37 emotional processing,Citation34,Citation38 and executive controlCitation39 undergo dramatic and rapid changes. The corresponding behavioral signatures that typically signify adolescence include suboptimal decisions and actions; incentive and seeking behaviors; emotional liability; stress in relation to social, working, and academic demands; and increased incidence of unintentional injuries, homicide and suicide attempts, and substance abuse.Citation32,Citation40 These behavioral changes are related to the onset of many psychiatric disorders, which increase sharply from childhood to adolescence,Citation41 with the lifetime risk for the emergence of mental illness peaking at age 14.Citation42,Citation43 Thus, adolescence is the period with nonlinearly increased onset of psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bipolar disorder (BP), depression, schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and anorexia nervosa (AN), relative to childhood and adulthood.Citation44–Citation52 Also, some of the most common child psychiatric disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and tic disorder (TD), can frequently cross into adolescent depression and OCD or exacerbate in adolescent patients.Citation53–Citation56

Importantly, the somatic, neuronal, behavioral, and psychological signatures of adolescence are associated with prominent maturational changes in sleep–wake cycle, and sleep timing, duration, and architecture – parameters during this developmental period reach those commonly observed in adults.Citation57–Citation61 These sleep changes are suggested to reflect neurobiological sleep regulatory mechanisms that undergo maturation during adolescence,Citation60–Citation62 global synaptic reorganization hallmarking this period,Citation63–Citation66 or rapid adaptation of the sleep–wake schedule in response to changes in environmental requirements.Citation57,Citation59

Given the vital importance of sleep, it can be concluded that adolescence is a critical period for normal growth and development in which sleep, in a complex association with many other processes, plays an important role. In this review, we will first present contemporary views about the complex neurobiology of sleep and its functions with implications for adolescence. Second, we will discuss existing complex relationships between common adolescent somatic/organic, sleep-related, and psychiatric disorders and certain sleep alterations.

Sleep physiology and architecture

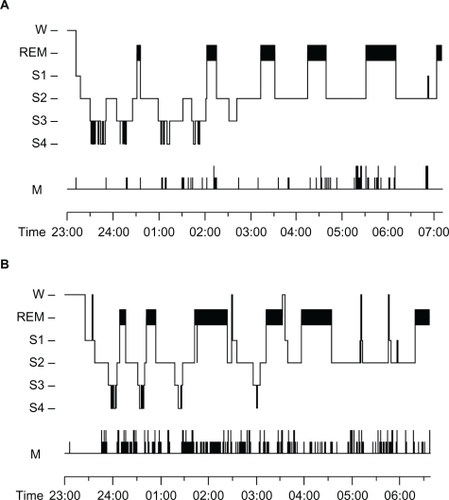

The heterogeneous nature of sleep can be seen in human and in most animal polysomnographic (PSG) records, which traditionally use electrophysiological techniques including electroencephalography (EEG), electromyography (EMG), and electro-oculography (EOG) to characterize sleep at system levels. Overnight human sleep is characterized by the cyclic occurrence of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and non-REM sleep, which includes lighter sleep (stages 1 and 2) and deeper, slow wave sleep (SWS) (stages 3 and 4).Citation67 These distinct sleep stages can be determined by their major electrophysiological signatures. SWS is hallmarked by EEG slow wave activity (SWA) comprising delta (1–4 Hz) waves and slow (<1 Hz) oscillations (SO),Citation68,Citation69 whereas REM sleep signatures include wake-like EEG activity comprising theta (∼5 Hz), beta (∼15–30 Hz), and gamma (>30 Hz) rhythms accompanied by swift occurrence of REM upon lack of muscle tone.Citation70–Citation72 Stage 2 of non-REM sleep is defined by presence of EEG sleep spindles oscillating at 12–15 Hz and K-complexes.Citation67,Citation73 Stage 1 of non-REM sleep represents a brief transition from wake to sleep, and is depicted as a replacement of waking EEG by theta or slower EEG rhythms paralleled by the appearance of very slow circular eye movements.Citation74,Citation75 Normally, sleep onset begins with a brief period of stage 1 non-REM sleep, which is subsequently followed by sleep deepening marked by the appearance of stage 2 non-REM sleep and a further progressive transition to stages 3 and 4 of SWS. The latter is followed by a relatively short transient of stage 2 non-REM sleep, after which a period of REM sleep appears. This sleep stage’s progression, and in particular, the non-REM–REM sleep alternation forms one sleep cycle of approximately 90 minutes duration, and about five or more such sleep cycles are usually observed in normal human overnight sleep.Citation67,Citation74,Citation75 Whereas SWS dominates the first half of the night, REM sleep and stage 2 non-REM sleep dominate the second half. This ultradian dynamic reflects the circadian regulation of sleep that is distinguishable from its homeostatic regulation seen after sleep deprivation.Citation76,Citation77 A typical PSG graph of a healthy adolescent’s overnight sleep is presented in .

Figure 1 Representative hypnograms of A) healthy adolescent and B) adolescent with depression.

Abbreviations: W, wake; REM, rapid eye movement sleep; S1, stage 1 of non-REM sleep; S2, stage 2 of non-REM Sleep; S3, stage 3 of non-REM sleep; S4, stage 4 of non-REM sleep; M, time of movements.

Implications for adolescence

For the purpose of this review, the following implications for adolescence can be ruled out. First, given that sleep displays a specific architecture built up by its distinct stages, it should be considered that the stages’ maturation during adolescence undergoes unequivocal changes. For example, a reduction of both SWS and REM sleep EEG signatures at the expense of a relative augmentation of stage 2 non-REM sleep EEG rhythms mark the transition from childhood to adolescence.Citation61 This indicates that the distinct sleep stages maturate more or less dissimilarly, and their regulation and functions differ. This issue will be discussed later. Second, other recent studies clearly show that a decline in EEG SWA during SWS occurring from childhood to adolescence topographically follows the global and extensive synaptic reorganization, or “pruning”, during adolescence, thus strengthening relevant synaptic networks over irrelevant ones.Citation63–Citation66 Therefore, it is the sleep architecture rather than sleep as a whole that matures during adolescence. Sleep architecture is vulnerable to a complex interaction between maturational, situational, and pathological changes in sleep during this period.

Sleep regulation

The regulation of sleep is active in its own right, and is closely related to its physiology and functions.Citation78 The respective neurobiological mechanisms are represented by complex reciprocal interactions between different neuronal populations and their chemical modulators and transmitters in distinct functional states across the sleep–wake cycle.Citation5,Citation79–Citation82 Two major brain regions are mostly considered in sleep regulation, especially when the functions of sleep and its alterations in various maturational and pathological conditions are concerned.Citation80,Citation83 The first engages neuronal populations located in the diencephalon. Briefly, these include: 1) the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus, which governs the circadian regulation of the sleep–wake cycle through circadian clock genes signaling to the rest peripheral cell oscillators, and couples the functional brain states with the nearby 24-hour light–dark cycle. Its neurons are active during wakefulness and just before sleep onset, thus oppose the homeostatic sleep drive and provide even periods of wake and sleep. 2) The ventrolateral preoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus, which consists of γ-aminobutyric (GABA)-ergic neurons that become prominently active during sleep onset and further in the course of sleep. 3) Hypocretin/Orexin (Hpcr/Orx) neurons in the lateral hypothalamus, which are active during wake and wane during sleep. Notably, along with their wake-promoting role, these neurons also regulate eating, sexual, and locomotor behaviors.Citation83 4) The histamine (His)-containing neurons in the tuberomammillary nucleus of the dorsal hypothalamus, which like Hpcr/Orx neurons are wake-active and wane during sleep. 5) The dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus, which is considered to integrate the hormonal signaling, including hypothalamo-pituitary axis (HPA), with the psychological and physiological functional states across the sleep–wake cycle.Citation84

The second brain region engages brainstem or mesopontine and basal forebrain nuclei spread in the reticular ascending system (RAS) and projecting noradrenalin (NA), serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT), and acetylcholine (Ach) neuromodulatory signals to the upper brain structures including basal ganglia and amygdala, thalamus, hippocampus, and cortex. During wake, the brainstem/mesopontine NA, 5-HT, Ach, and the hypothalamic His neurons projecting to the upper brain structures and cortex are all active, thus sustaining optimal functioning of the different brain states for environmental requirements.Citation5,Citation79,Citation80 As sleep deepens from stages 1 and 2 to SWS, all these neurotransmitters progressively decrease their activities, with their lowest during SWS. This results in strongly diminished or lacking ascending projections of RAS neuromodulation to the upper brain structures and cortex, which in turn is responsible for the non-REM sleep EEG signatures originating from thalamocortical and corticocortical interplay as reflected by the sleep spindles, K-complexes, and SWA.Citation80,Citation85,Citation86

In REM sleep, all NA, 5-HT, and His neurons cease their firing. Instead, an Ach excessive overactivity emerges projecting to the cortex and all subcortical structures and cortical areas, which results in occurrence of the electrophysiological signatures of REM sleep.Citation79,Citation80

Further concerning the mesopontine and basal forebrain sleep regulatory systems, it should be noted that they work by reciprocal interactions between the so-called REM-off, silent in REM sleep (NA-adrenergic and 5-HT-ergic neurons in locus coeruleus and dorsal raphe, respectively), and REM-on, active in REM sleep (tegmental and pedunculopontine, Ach-ergic, and glutamatergic neurons) through GABA interneurons and NA-ergic autoreceptors. These mechanisms of sleep regulation are essential for the ultradian alternating expression of non-REM–REM sleep periods.Citation79,Citation80,Citation87,Citation88

Concomitantly, important reciprocal interactions among peptides, such as growth hormone (GH)-releasing hormone (GHRH) and corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), play a role in ultradian sleep regulation. GHRH is active and GH inhibits HPA hormones, with the CRH as indicated by the cortisol release being suppressed to a minimum during the early, rich in SWS sleep, portion of night. By contrast, HPA activity and cortisol levels reach their peak during late, rich in REM, sleep at night.Citation81,Citation82

Although the levels of brain dopamine (DA) activity have not been shown to vary substantially across sleep–wake stages,Citation89 more recent data indicate an important role for the mesopontine DA-ergic system in the regulation of timing and duration of distinct sleep stages, and in particular REM sleep.Citation90,Citation91 However, the DA role in sleep regulation is still elusive.

Implications for adolescence

The following implications for adolescence should be regarded concerning sleep regulation.

Sleep and its regulatory mechanisms maturate from infancy to late adolescence.Citation60 For instance, the human newborn exhibits an even distribution of waking, REM sleep, and SWS, spending about 8 hours in each state. After birth, there is a gradual decrease in REM sleep from about 8 hours at birth to about 1 hour by age 15, beyond which there is a small decrease until senescence. The gain observed in total waking time, from about 8 hours at birth to about 16 hours at maturity, is mostly at the expense of REM sleep duration.Citation60 Animal studies indicate that the neural substrates responsible for these developmental changes in sleep–wake cycle are located in the brainstem or mesopontine/basal forebrain nuclei involved in regulation of the ultradian expression of non-REM–REM sleep alternation, as described previously. These sleep regulatory mechanisms have been suggested to comprise the so-called developmental REM sleep-suppressing system,Citation92–Citation94 which may be altered and/or not adequately matured in a spectrum of psychiatric disorders during development, including pubertal schizophrenia, panic attacks, PTSD, and anxiety depression – all exhibiting REM sleep overdrive.Citation93,Citation95 Moreover, if not properly treated, these disorders can cross into adulthood. Also, the impaired REM sleep regulation during development may lead to occurrence of major depression, insomnia, Alzheimer’s, Huntington’s, and Parkinson’s diseases later in life.Citation93,Citation95 Also in this context, depressive disorders are strongly associated with an increased secretion of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and subsequent increased cortisol levels. Both increased CRF and cortisol adversely affect sleep, thus producing delayed sleep onset, shortened REM sleep latency, increased REM sleep, reduced SWS, and increased light sleep.Citation82,Citation95 A typical PSG of an adolescent with depression is shown in .

Further, sleep in adolescents displays later sleep onset associated with earlier morning awakenings and relatively shorter duration compared with that in children. This may reflect maturational alterations of sleep’s circadian regulation, its adjustment to environmental changes, or both.Citation96,Citation97 Moreover, the dysfunctional thoughts, worries, anxiety, ruminations, and unfavorable beliefs adolescents have, all result in hyperarousal, which delays sleep onset, provokes awakenings after sleep onset, and increases early morning awakening.Citation98,Citation99 From a neurobiologic and neurocognitive point of view, it should be emphasized that the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus interacts with both suprachiasmatic and ventrolateralpreoptic nuclei. As described previously, this nucleus is more than a mere relay, and is believed to integrate cognitive and emotional information with neuroendocrinological processes as well as to trigger and modulate physiological arousal. As a result, cognitive-emotional arousal seems to increase physiological arousal and disrupt sleep via the interaction of the hypothalamic nuclei.Citation84 Thus, it might be proposed that maturation of circadian sleep regulation or its adjustment to sleep–wake schedule in adolescence are very fine processes that might be substantially affected by the nonlinear behavioral changes during this developmental window.

Contemporary interpretation of the functions of sleep

Given the heterogeneous nature of sleep, it has been recently well established that its distinct sleep stages and their specific EEG signatures contribute dissimilarly to its functions. In general, whereas non-REM sleep contributes to energy conservation and synaptic homeostasis as reflected by the use-dependent sleep changes, REM sleep is proposed to serve neuronal recuperation and emotional regulation.Citation2,Citation3,Citation7,Citation10,Citation24 More specifically, non-REM sleep, particularly SWS, provides conditions for brain plasticity at system and neural levels to take place, whereas REM sleep provides the soundest basis for brain plasticity at synaptic and genetic levels.Citation8,Citation9,Citation100,Citation101 Both non-REM sleep and REM sleep provide these conditions through their specific neuromodulatory activities and EEG signatures, as described earlier in the respective sections. Accordingly, the cognitive and psychological functions of non-REM and REM sleep are recently distinctly differentiated.

Recent studies demonstrate that SWS and the portion of non-REM sleep immediately before SWS actively consolidate memories, with the EEG delta waves, SO, and spindles playing a critical role for this memory consolidation.Citation102–Citation104 Neuroimaging data strongly indicate that the memory consolidation during SWS involves transfer of previously acquired memories stored in the hippocampus from the hippocampus to the cortex by the so-called hippocampal–cortical dialog,Citation105–Citation107 which suggests that SWS also provides conditions for a reprocessing or reconsolidation of the previously learned material.Citation108,Citation109 Indeed, it is shown that early night sleep that is rich in SWS transforms previously acquired implicit knowledge into explicit knowledge, solving the task.Citation15 A later study using the same paradigm revealed the EEG mechanism of this transformation during SWS: slow spindle (8–12 Hz) EEG activity, which is clearly distinguishable from the use-dependent changes (SWA and fast spindles) in response to presleep task performance.Citation110

Another important signature of non-REM sleep stage 2 sleep spindles, is associated with cognitive abilities,Citation20,Citation21,Citation111 and a recent study in children demonstrates stage 2 spindles beneficial for coping strategy in response to stress.Citation29

REM sleep, its neurobiology and dreaming mental signature have been proposed to serve complex cognitive and psychological functions.Citation78,Citation112,Citation113 Indeed, REM sleep has been shown to facilitate access to weak associations, thus promoting human heuristic creativity,Citation12,Citation13,Citation114,Citation115 and late night REM sleep has been demonstrated to preserve previously learned implicit knowledge.Citation15 Although it has been consistently found that REM sleep consolidates mostly procedural memory,Citation116–Citation120 more recent studies suggest a permissive rather than immediate effect of REM sleep on memory.Citation103,Citation121,Citation122 Thus, the role of REM sleep is proposed to be related to integration of recently consolidated memory in a more general and individually specific context.Citation123

Notably, REM sleep may have an important role in selective facilitation of affective memories. Earlier studies revealed the social aggression of interaction signature in dreams during REM sleep compared with those during non-REM sleep,Citation26,Citation27 which suggests that the process of REM sleep mental activity aids in the resolution of previous emotional conflict.Citation124 Indeed, REM sleep and its EEG signature, theta EEG activity, were shown to benefit consolidation of fact-based information with negative emotional salience, thus suggesting that REM sleep has a role in emotional processing.Citation22–Citation24,Citation125 However, these features of REM sleep and their respective neural grounds, if improperly set, may lead to the development of a variety of psychiatric disorders with affective component.Citation24,Citation126,Citation127 A recent observation in children and adolescents points to a bidirectional role for REM sleep in cognitive abilities and psychopathological expression depending on the presence or absence of psychiatric disorders.Citation18

Implications for adolescence

Considering the above-described sleep stages specific functions, the major implication for adolescence is that preserving normal overnight sleep architecture appears critically important for successful physical, cognitive, and psychological functioning. The sleep architecture of a healthy adolescent in comparison with that of a depressed adolescent is shown in . As can be seen in the figure, compared with the PSG of the healthy adolescent (), the PSG of the depressive adolescent is characterized by delayed sleep onset, less time spent in sleep and in SWS, shortened latency to REM sleep, and augmented REM sleep duration, all accompanied by more arousals as reflected in the movement time (). This implies that the depressive adolescent patient experiences far less physical, cognitive, and psychological benefits from his/her sleep compared with the healthy subject.

In this regard, a number of common adolescent conditions beyond highly specific somatic and psychiatric disorders during this developmental period could substantially affect sleep architecture, and thus may lead to maladaptive functioning, including obesity, poor academic achievement, and decremented psychological processing. These conditions include making suboptimal decisions and actions, emotional liability, stress in social relationships with peers, increased incidence of unintentional injuries, violence, substance abuse, and excessive use of online gambling and electronic media.Citation57,Citation59,Citation128–Citation133 These behaviors that typically hallmark adolescenceCitation32,Citation40 are accompanied by psychological and physiological hyperarousal and related chronic sleep loss,Citation98,Citation99 which in turn can deteriorate synaptic plasticity, especially during development.Citation134 Therefore, such behaviors in adolescence in association with sleep alterations may be regarded as preconditions of developmental psychiatric disorders.

Interestingly, the relationship between these adolescent conditions and altered sleep architecture seem to be bidirectional. For example, poor or insufficient sleep in adolescents is shown to be associated with increased incidents of unintentional injuries and increased risk at suboptimal decisions.Citation135 In parallel, excessive use of psychotropic substances, such as alcohol, benzodiazepines, and cannabis, which is associated with suboptimal decisions, in turn produces alterations of sleep architecture including reduction of SWS and REM sleep through action of these substances on GABA-A receptors.Citation82 Indeed, such a bidirectional relationship between substance use and sleep disturbances in adolescents is proposed and it is concluded that treatment of both sleep problems and substance use should be considered.Citation136

Furthermore, the emotional liability, stress, and homicidal/suicidal thoughts that are characteristic of adolescence are commonly associated with increased HPA activity and substantial increase in both REM sleep and nightmares, and the later sleep alterations are considered as predictors of PTSD and depression in adolescence.Citation137,Citation138 A bidirectional relationship between psychological adolescent problems and altered sleep architecture is also supported by some epidemiological observations. For example, it is reported that among a large sample of 99,668 adolescents aged 12–18 years, shorter sleep duration was related to worsened psychological status. Two years later, the follow-up evaluation of the same sample revealed that the relation between poor sleep and poor psychological status remained stable over time.Citation139

Many strategies are proposed to restore altered sleep architectures related to common but not pathological conditions in adolescence, including behavioral intervention and psychotherapy, yet regular physical exercise appears to be one very promising tool. For example, adolescents who played football three times a week displayed better sleep efficiency, more SWS, and less REM sleep compared with age-matched subjects who did not, with this effect being longlasting.Citation140 The possible reason for this finding could be that general use-dependent sleep changes in response to the physical activity, which may be suggested to normalize altered sleep architecture.

Common organic diseases and sleep alterations in adolescence

In this section, altered sleep in adolescents undergoing cleft lip and/or palate surgery and chemotherapy for oncologic diseases is reviewed.

Cleft lip and/or palate

Orofacial clefts (OFCs) are the most frequent birth defects worldwide. One in 500–700 newborns suffers from OFC.Citation141,Citation142

It is still a matter of debate as to whether a repaired cleft lip and/or palate (CL/P) is related to impaired sleep. Since the occurrence of repaired CL/P does not seem to lead to impaired sleepCitation143 or to affect psychological functioning in children and adolescents, sleep could be adversely affected if breathing is concomitantly impaired due to the occurrence of CL/P. In this respect, MacLean et alCitation145,Citation146 and Muntz et alCitation147 reported poor sleep in children and adolescents with CL/P in two specific cases: 1) if CL/P was inadequately or only partially repaired; 2) if CL/P was associated with further structural abnormalities of the airway. In these cases, the risk of sleep-disordered breathing was increased. Similarly, Muntz et alCitation147 also reported an increased risk of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), though with significant improvement after surgical repair.

Sleep in children and adolescents undergoing chemotherapy

Whereas incidence rates for cancer in children and adolescents are very small, accounting for about 44 cases per 1 million individuals per year,Citation148 the subjective burden both for parents and children is tremendous. The reason for assessing sleep in children and adolescents suffering from cancer and undergoing chemotherapy stems from the observation that poor sleep is related to poor psychological functioning. Thus, preventing or reducing poor sleep is considered a possible means of reducing any further psychological burden during chemotherapy. However, data are scarce. Walker et alCitation149 investigated subjective sleep patterns and the sleep hygiene of 51 adolescents (range: 10–19 years) prior to and during chemotherapy. Adolescents during chemotherapy reported significantly poorer sleep quality and sleep hygiene behaviors, when compared with normative data from healthy controls. But when compared with normative data from adolescents suffering from chronic pain, the opposite was true, with significantly better sleep quality and sleep hygiene behaviors in adolescents during chemotherapy. Within-group comparisons further revealed that during chemotherapy the sleep–wake pattern was similar to the weekend sleep–wake pattern but dissimilar to the weekday sleep–wake pattern prior to chemotherapy. This pattern of results suggests that during the chemotherapy of this sample a shift occurred to later bedtimes, longer sleep duration, and prolonged sleep in the morning hours. Whereas in this study the underlying mechanisms remained unclear, possible answers are provided by the study conducted by Zupanec et al.Citation150 The authors investigated children and adolescents undergoing maintenance chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and observed a variety of different factors causing altered sleep in the majority (87%) of children. Among these, side effects of medication and changed sleep habits were often reported. By contrast, factors such as sleeping with someone, comforting activities and routines, favorable effects of medications, and food and drink were reported to contribute substantially to favorable sleep. Next, Rosen and BrandCitation151 investigated sleep and daytime sleepiness in 53 children suffering from various cancers by using polysomnography, multiple sleep latency test, and actigraphy. The authors observed that children with neoplasms of the central nervous system (CNS) involving the hypothalamus, thalamus, and brainstem had the most frequent and severe sleep problems. Moreover, excessive daytime sleepiness was the most common sleep problem, seen in 60% of children with cancer and in 80% of children with CNS neoplasms involving the hypothalamus, thalamus, and brainstem. Moreover, sleep-disordered breathing was present in 40% of the entire group of children with cancer and in 46% of children with neoplasms in the hypothalamus, thalamus, and brainstem. In children suffering from leukemia, 39% complained of insomnia. The causes of the sleep problems ranged from neurological injury caused by the neoplasm and the CNS-directed treatments to seizures, adenotonsillar hypertrophy, side effects of medication, obesity, pain, anxiety, and drug abuse. Rosen and BrandCitation151 further observed that some of the sleep problems were present before the diagnosis of cancer, though most developed after treatment initiation, and that the treatments were generally successful if sleep problems and their causes were correctly identified and treatments were directed to the specific cause of the problem.

To summarize, alterations in sleep patterns are often observed in children and adolescents suffering from cancer and undergoing chemotherapy. If, on one hand, specificity for the cancer medication side effects and concomitant diseases reduce sleep, on the other hand, factors such as sleeping with someone, comforting activities and routines, favorable effects of medications, and food and drink can be considered as protective factors.

Sleep-related disorders in adolescence

This section will review some commonly observed sleep-related disorders in adolescence, including OSA, snoring, periodic leg movements in sleep (PLMS), and restless legs syndrome (RLS).

OSA and snoring in children and adolescents

Estimates of children and adolescents suffering from OSA range from 1%–3%,Citation152–Citation154 while regular snoring is observed in up to 12% of children.Citation154 Snoring and OSAs are considered to be closely related to malformations of the oral cavity, namely to adenotonsillar hypertrophy and to congenital malformations often related to CL/P.Citation144

OSA during adolescence represents a serious condition that can substantially impair sleep architecture and a number of physical and cognitive functions. The cognitive consequences include daytime somnolence, learning disabilities, and deficient memory consolidation.Citation155–Citation158 The physical consequences are described as the so-called metabolic syndrome, which includes obesity, diabetes, immune deficits, and cardiovascular problems.Citation159,Citation160 For example, Tran et al investigated 42 children (mean age: 5.8 years) with OSA confirmed by positive findings on PSG and undergoing tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy and 41 control children (mean age: 7.3 years) with no history of snoring.Citation153 All children were assessed twice for emotional, social, and behavioral functioning. Before surgery, children with OSA had significantly poorer scores for internalizing and externalizing problems and somatic complaints compared with healthy controls. After tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy, internalizing and externalizing problems and somatic complaints had significantly decreased in children with OSA and they no longer differed statistically from healthy controls. However, Mitchell reported less optimistic findings from 79 children and adolescents aged 3–14 years with OSA undergoing surgical repair.Citation161 Whereas sleep and respiratory values, as assessed by polysomnography, generally improved dramatically after surgery, changes in children’s quality of life as assessed by parents’ judgments were also significant, though, most importantly, adversely related to surgery outcome.

Since adolescents tend to have poor compliance with the noninvasive positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy for OSA, data about the effect of PAP therapy on physical, cognitive, and psychological functioning in children and adolescents are inconsistent.Citation162 Yet, a recent study demonstrated that obese adolescents with OSA who adhered to PAP treatment displayed improvement in attention and academic functioning relative to adolescents with OSA who underwent PAP therapy but did not adhere to it.Citation163

To summarize, successful surgical intervention in children and adolescents suffering from OSA brings about dramatic improvements in respiratory and sleep outcome. These improvements may be accompanied by improvements in psychological functioning and behavior,Citation153 though not necessarily in a global score of quality of life.Citation161 The reason for this heterogeneous pattern of results remains elusive, though differences related to samples (sample size, age, degree of OSA, and concomitant malformation of the oral cavity), assessment tools, and surgery outcome may all contribute to this heterogeneous picture. Similarly, PAP treatment shows positive effects on OSA and related daily behaviors in adolescents but only when adolescents adhere to it.Citation163

With respect to snoring, Blunden et al investigated the neuropsychological and psychosocial functioning of 64 children.Citation164 Of these, 11 were snorers, 13 reported behavioral sleep problems, and 9 reported both snoring and behavioral sleep problems. The remaining 31 were age and gender-matched controls. All children underwent psychological (Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence®, Children’s Memory Scale®, Test of Everyday Attention®, and Auditory Continuous Performance Test®) and psychosocial assessment (Child Behavior Checklist). Results showed a differentiated impact of snoring and behavioral sleep problems in that snoring was associated with intelligence and attention deficits whereas behavioral sleep problems were associated with memory and behavioral deficits.

To conclude, numerous studies based on different methodologies, samples, and outcome variables suggest that sleep and psychological functioning are also affected in children and adolescents suffering from impaired respiratory functions.

PLMS and RLS in children and adolescents

PLMS disorder is unique in that the movements occur during sleep. The condition is remarkably periodic. PLMS may occur with other sleep disorders and is related to, but not synonymous with, RLS. The latter is a sensorimotor disorder characterized by an irresistible urge to move the legs, often accompanied by uncomfortable sensations, which is relieved by movement and worse in the evening or night and at rest.Citation165 It is believed that alterations in brain dopaminergic systems and iron deficiency cause their core symptoms.Citation166–Citation171 Whereas prevalence rates for adults range from 5%–15%, data about the rate of PLMS and RLS in children and adolescents are largely inconsistent because these motor sleep disturbances are shown almost always coexisting with ADHD, TD, anxiety, and depression in children and adolescents.Citation168,Citation170,Citation172,Citation173 Furthermore, since alterations in brain DA systems and iron deficiency are also shown to underlie ADHD and TD psychopathology in children,Citation55,Citation167,Citation168,Citation174,Citation175 is suggested that RLS, ADHD, and TD form a spectrum of comorbid conditions.Citation170,Citation175 Interestingly, however, complaints of poor sleep in relation to PLMS and RLS among large samples of children and adolescents were shown to be more in adolescents than in children.Citation170

Given the extremely high rate of PLMS asnd RLS comorbidity in ADHD, TD, and other psychiatric conditions in children and adolescents, there is little information about how these motor sleep disorders, if present alone, affect daily functioning. Yilmaz et al investigated 3304 high school adolescents aged 15–18 years.Citation176 Participants completed a series of questionnaires related to sleep, RLS, and psychological functioning. Results showed that RLS was diagnosed in 3.6% of participants. Occurrence of RLS was associated with nocturnal bed-wetting, sleeping difficulty, daytime sleepiness, and, most importantly, with hyperactivity/inattention. With respect to PLMS and RLS comorbidity in ADHD, Chervin et al investigated 866 children and adolescents aged 2.0–13.9 years.Citation172 First, they found that prevalence of RLS was about 17% and, second, that RLS and PLMS were associated with an increased risk for suffering from inattention and hyperactivity.

Concerning the pharmacological treatment of PLMS and RLS, psychostimulants such as DA agonists have been proved effective; however, given the high rate of both sleep motor disorders in children and adolescents with ADHD, TD, and other psychiatric disorders, this therapy should be adjusted and linked to the leading condition.Citation170 In this regard, one promising treatment strategy may be iron supplementation.Citation168,Citation175

In conclusion, PLMS and RLS may affect both sleep and daily functioning and thus may lead to impaired development and poor academic achievement in adolescents. However, when subjectively reported or documented by PSG, PLMS and RLS should be treated with increased attention with respect to concomitant psychiatric disorders.

Sleep and common adolescent psychiatric disorders

In this section, the relationship between sleep alterations and ADHD, OCD, eating disorders, anxiety, and adolescent depression in adolescence will be reviewed. As introduced previously, the incidence of all these psychiatric disorders nonlinearly increases from childhood to adolescence, and their prevalence in teens is higher relative to children and adults.

Sleep and ADHD in children and adolescents

ADHD is one of most common and socially important child psychiatric disorders. Onset is already observed in early childhood with a boy-to-girl ratio of 5:1. In school-age children, prevalence rates are about 5% to 12%, and, if untreated, ADHD crosses into adolescence and adulthood with more severe symptoms accompanied by substance abuse, antisocial behaviors, depression, and poor academic achievement.Citation53,Citation54,Citation177,Citation178 Along with its core symptoms, inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity, altered sleep is a common feature in ADHDCitation179–Citation181 to the extent that sleep problems may be related to increase in ADHD symptoms during the day.Citation182–Citation186

Although sleep in ADHD is a subject of extensive research, the PSG data concerning alterations of sleep architecture in ADHD are largely inconsistent. Two meta-analyses did not provide conclusive views of whether ADHD is hallmarked by specific sleep changes. Rather, these meta-analyses showed that sleep in children with ADHD was characterized by high prevalence of OSA, PLMS, and RLS as well as by prolonged sleep onset, less actual time spent in sleep and worsened sleep efficiency, and frequent arousals.Citation180,Citation181 This inconsistency probably results from numerous confounders such as uncontrolled psychiatric and sleep-related comorbidities, loose diagnosis of ADHD without structured interviews, small sample sizes, inappropriate matching of groups for gender and age, and lack of medication control.Citation179,Citation181,Citation187 Therefore, for the purpose of this review, we will present PSG findings from some studies where such confounders were minimized.

For example, Golan et al examined sleep architecture in 32 children and adolescents with ADHD (mean age: 12.4 years; 26 boys/8 girls) and 32 controls (mean age: 12 years; 21 boys/11 girls) and found more REM sleep in ADHD patients relative to controls.Citation183 Of the ADHD patients, 15% had signs of sleep-disordered breathing occurring predominantly in REM sleep that was associated with their decreased vigilance on the next day as measured by multiple sleep latency test.Citation183 Similarly, Kirov et al compared sleep pattern in 17 boys diagnosed with ADHD (mean age: 11.2 years) with 17 healthy boys (mean age: 11.2 years) and found an REM sleep increase in the ADHD patients.Citation187 Later, the same authors also found an increased REM sleep in 18 children and adolescents with ADHD (mean age: 10.94 years; 17 boys/1 girl) compared with 18 controls (mean age: 11.58 years; 16 boys/2 girls). Importantly, the increased REM sleep in ADHD patients correlated positively with their core symptoms as assessed by Conners’ Parents Rating Scale® and Child Behavior Checklist.Citation185 By contrast, Gruber et al found less REM sleep in 15 prepubertal children (mean age: 8.93 years; 10 boys/5 girls) compared with 23 controls (mean age: 8.61 years; 13 boys/11 girls).Citation188 More recent studies also show a relationship between sleep in children and adolescents with ADHD and their daily cognitive functioning. For example, Gruber et al showed that 1 hour of sleep deprivation in an ADHD cohort strongly reduced attention capabilities and increased ADHD symptoms from subclinical to clinical values.Citation189 Another recent observation demonstrated that in children and adolescents with ADHD, REM sleep amount correlates positively with inattention scores and negatively with performance intelligence quotient.Citation18

These findings demonstrate altered sleep architecture in children and adolescents with ADHD as well as decrements in arousal, cognitive, and psychological functioning in association with the sleep alterations. Thus, a bidirectional relationship between altered sleep in ADHD patients and their daily symptom expression and functioning may be suggested. Both REM sleep abnormalities and sleep disorders in ADHD may play roles in increasing and maintaining symptoms of ADHD. However, given the largely inconsistent sleep findings in ADHD, this issue needs further evaluation.

The DA agonist methylphenidate hydrochloride (MPH) is a drug of choice for treatment of ADHD.Citation174,Citation190 However, since it is evident that sleep alterations in ADHD also need to be treated, and because methylphenidate may cause adverse effects on sleep in ADHD through action on the mesopontine DA regulatory system,Citation90,Citation91 extended release formulations of methylphenidate appear promising. They are usually given in the mornings, and copy the daily expression of ADHD symptoms, presumably without effects on DA neuromodulation in the evenings, at habitual bedtimes, and during sleep.Citation190,Citation191 Finally, a recent review suggested that pharmacological treatment of ADHD with MPH had no short- or long-term effects on children’s and adolescents’ sleep.Citation192

Sleep in adolescents with OCD and eating disorders

We discuss sleep changes in OCD and eating disorders together because they share common behavioral traits, obsession, and compulsion. OCD and eating disorders typically begin in adolescence or young adulthood, are seen in as many as 1 in 200 children and adolescents in relation to rapidly increased psychological vulnerability during this developmental period, and are frequently coexisting with other psychiatric conditions, including ADHD, TD, anxiety, and PTSD.Citation33,Citation52,Citation180,Citation193,Citation194 Whereas much attention has been given to the relationship between sleep and many emotional and behavioral disturbances and psychiatric disorders including ADHD and depression in children and adolescents, less is known about sleep changes in adolescents with OCD and eating disorders.Citation195–Citation198

OCD is characterized by recurrent intense obsessions and/or compulsions that cause severe discomfort and interfere with day-to-day functioning. In OCD, the obsessions and compulsions cause significant anxiety or distress, and they interfere with the child’s normal routine, academic functioning, social activities, or relationships.Citation177 Thus, it could be intuitively proposed that adolescents with OCD may be more likely than healthy peers to experience sleep problems for several reasons including heightened levels of OCD-related general anxiety and engagement in rituals before or during the bedtime routine that interfere with sleep onset. Although scarce, information about sleep alterations in adolescents with OCD confirms the above speculation. For example, a study of 18 pediatric OCD patients (9 adolescents with OCD and 9 matched healthy controls) reported that adolescents with OCD exhibited a number of sleep alterations including reduced sleep efficiency, increased sleep onset, and longer sleep latency to sleep stages.Citation199 In another study examining OCD-related impairment across multiple domains, Piacentini et al reported that 66% of parents noted that OCD interfered with their child “getting ready for bed at night” and “sleeping at night”.Citation200 However, other studies in adolescent and adult OCD patients infer presence of disorder-specific changes in sleep. For example, shortened REM sleep latency and increased REM sleep as well as an overnight oversecretion of adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) and cortisol were observed in patients with OCDCitation201–Citation203 – these observations were discussed in relation to 5-HT deficit in OCD.Citation201 Thus, relationships between sleep architecture changes and OCD symptoms, particularly in adolescent patients, need further studies.

Eating disorders primarily affect adolescent girls and young adult females and are considered to be rare among males. These include AN, binge eating (BE) (also known as compulsive overeating), bulimia nervosa (BN), and sleep-related eating disorder (SRED). AN is characterized by self-starvation and excessive weight loss, including psychiatric symptoms such as intense fear of weight gain or being “fat” and feeling “fat” or overweight despite dramatic weight loss, and is behaviorally expressed by sore throat and painless swelling of the cheeks from vomiting. BE is primarily characterized by periods of uncontrolled, impulsive, or continuous eating beyond the point of feeling comfortably full. Behaviorally, it is characterized by eating large amounts of food when not physically hungry, rapid eating, feelings of disgust, depression, or guilt with overeating. Patients with BE usually do not purge afterward by vomiting or using laxatives. Diagnosis of BN is more difficult than AN and BN; girls with BN try to remain at normal body weight or above while binge eating and purging.Citation204 Patients with SRED generally arouse from sleep and eat roughly 2–3 hours after sleep onset. Eating episodes are characterized by rapid ingestion of food that the patient usually reports as “out of control” or compulsive in nature.Citation204,Citation198

Since general anxiety and engagement in rituals before or during the bedtime routine are common in eating disorders,Citation198,Citation205 the sleep alterations seen so far in female adolescents with AN, BE, BN, and SRED may be proposed to share common features with those observed in OCD adolescents. Indeed, a retrospective sleep evaluation by means of questionnaires in 400 young female adults with AN and BN revealed a generally disturbed sleep;Citation196 this observation is consistent with previous PSG finding in females suffering from SRED.Citation198 However, more precise sleep evaluation by means of PSG in female adolescents consistently found a reduction of EEG SWA (0.5–4.5 Hz), in which sleep alteration was associated with the neurobiological consequences of the malnourished state.Citation206,Citation207

Further concerning sleep changes in eating disorders, it should be emphasized that hypothalamic Hpcr/Orx neurons are involved in either sleep regulation or eating behavior,Citation83 and a genetic study among females with eating disorders proposes the involvement of alterations in Hpcr/Orx system in these patients.Citation208

The behavioral consequences from altered sleep in both OCD and eating disorders include daily somnolence and fatigue and worsened academic performance.Citation196,Citation198,Citation209 Eating disorders accompanied by loss of weight or obesity in turn may produce sleep alterations.Citation198,Citation206,Citation210

Pharmacotherapy for both OCD and eating disorders include 5-HT reuptake blockers and hypnotics and, particularly for the eating disorders, also DA agonists and codeine.Citation201,Citation211,Citation212 However, benzodiazepine and nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics reduce SWS and REM sleep at the expense of lighter non-REM sleep stages,Citation82 the effects of which are proposed to impair synaptic plasticity.Citation213 Furthermore, psychostimulants are all shown to reduce REM sleep.Citation214 Since non-REM and REM sleep regulatory mechanisms develop during adolescence and their normal overnight expression is important for growth and development, the pharmacotherapy in OCD and eating disorders should be supplemented by prevention of non-REM and REM sleep abnormalities. Prevention strategies may include psychological interviews, attendance at educational lectures, sleeping in presence of parents or peer healthy adolescents, and practicing physical exercises.

Sleep in adolescents with anxiety disorders and depression

The rate of anxiety disorders and adolescent depression rapidly increases in teens and is higher during this developmental period relative to childhood and adulthood.Citation42 The rapid peaking of these psychiatric conditions in teens is associated with the behavioral changes that hallmark adolescence.Citation32,Citation40 Also, as mentioned earlier, it should be emphasized that anxiety disorders and adolescent depression may represent comorbid conditions in adolescent ADHD, TD, OCD, PTSD, and eating disorders.

Evidence from pediatric samples of patients with anxiety disorders suggests that sleep problems are prevalent and related to anxiety severity. Several studies examining the clinical presentation of pediatric generalized anxiety disorder have found rates of sleep disturbances to range from 42 to 66%.Citation215–Citation217 In a representative study of clinically anxious adolescents (n = 128) with generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and/or separation anxiety disorder, it was observed that 88% of youth complained of at least one sleep problem, with over 55% experiencing more than three sleep-related problems, including insomnia (66.6%), nightmares (54.5%), refusal to sleep alone (47.9%), being overtired without good reason (43.2%), refusal to sleep away from home (40.9%), decreased sleep (36.9%), and sleep walking/talking (22.7%). Moreover, these sleep problems were positively related to measures of anxiety severity.Citation218 Among nonclinical pediatric samples, Mindell and Barrett found a positive relationship between nightmares and trait anxiety, with more than three nightmares per week being related to parent proxy reports of clinically significant anxiety levels.Citation219 Since it is unclear whether and how sleep problems in adolescents with anxiety disorders may affect their day-by-day well-being, this issue mandates focused investigations. Also, treatment of both anxiety disorders and related sleep problems in adolescence is so far overlooked because these problems are frequently included in the broad spectrum of behavioral changes hallmarking adolescence. However, high incidence of neuroticism associated with poor sleep and nightmares mandates increased attention because such behavioral and sleep problems may be preconditions for serious psychiatric disorders, including depression.Citation138

The increased onset of depression at adolescence is a factor with highly increased risk of decrements in growth and development and further problems in adulthood.Citation42 Early depressive episodes recur or persist into adult life along with ongoing psychosocial difficulties, including disruption in interpersonal relationships, low educational attainment, poor occupational functioning and unemployment, as well as elevated risk for suicidal behavior.Citation220 Given the growing economic and psychosocial burden associated with juvenile depression, the identification of youth at highest risk for the illness will have great public health impact.Citation221

Prospective epidemiological studies have demonstrated that sleep disturbances increase the risk for depressive disorders.Citation222,Citation223 Sleep PSG alterations found in adolescent depression were shown to be the same as in adults, and thus sleep measures appear an additional diagnostic tool. These sleep alterations include shortened latency to REM sleep and increased REM sleep amount, delayed sleep onset and insomnia, more time spent awake after sleep onset, and less SWS than in healthy subjects.Citation138,Citation224–Citation226 Notably, sleep in depressive adolescents is shown to be additionally characterized by increased overnight occurrence of both OSAsCitation227 and PLMS or RLS.Citation131 A typical hypnogram of adolescent depressive patient is shown in . These sleep signatures of adolescent depression are accompanied by elevated HPA activity and increased cortisol levels.Citation138,Citation225 Further, depressive adolescents suffer from heavily increased incidence of nightmares compared with healthy peers,Citation138,Citation228,Citation229 which is associated with the elevated REM sleep.Citation230

The daily functioning of depressive patients is characterized by overall worsening of cognitive and academic abilities, as well as by emotional disregulation, which includes negative emotional tone and increased retrieval of emotional memories with negative affect.Citation231,Citation232 Also, patients with depression display a self-related memory consolidation instead of the normal consolidation of memories.Citation231 Although it is not clear whether the worsened cognitive and psychological functioning in teens is disorder-associated or a result of the strongly altered sleep architecture, bidirectional relationships between these may be proposed.

Depression is a subject of extensive psychopharmacological treatment, including psychostimulants acting on 5-HT and NA reuptake mechanisms and benzodiazepine and nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics, in combination with psychotherapy.Citation233 Given the complex role of sleep and its regulatory mechanisms for the normal physical, cognitive, and psychological functions during adolescence, timely management of sleep problems related to the behavioral and psychopathological conditions that rapidly undergo nonlinear changes in teens appears an important strategy for both minimizing the risk at depression and its prevention during this developmental period.

Conclusion

Adolescence is a critical growth and development period hallmarked by drastic and nonlinear hormonal, somatic, and behavioral changes, which are paralleled by dramatic maturational changes in sleep physiology, architecture, and regulatory mechanisms. Thus, sleep, in a complex association with many other processes, appears to play a critical role in normal functioning during adolescence.

There is a strong increase in many inappropriate behaviors, pathological somatic and psychological conditions, and psychiatric disorders in adolescence relative to childhood and adulthood. All these conditions are accompanied by more- or less-specific sleep alterations. Given that sleep and its specific architecture serves vitally important physiological, cognitive, and psychological processes, a bidirectional relationship between its maturational or pathological alterations and common somatic, cognitive, and psychiatric conditions in adolescence may be suggested to exist. Accordingly, the sleep alterations in these common adolescent pathological conditions may in turn worsen their symptom expression, and thus may lead to a number of additional somatic complications, poor academic achievement, and poor psychological well-being. Therefore, treatment of all these common adolescent conditions should also consider the alterations of sleep. This mandates an increased attention to both sleep changes in adolescence and common adolescent pathological conditions by parents, pediatricians, psychiatrists, and sleep researchers.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- CirelliCTononiGIs sleep essential?PLoS Biol20086e21618752355

- SiegelJMClues to the functions of mammalian sleepNature20054371264127116251951

- SiegelJMSleep viewed as a state of adaptive inactivityNat Rev Neurosci20091074775319654581

- DingesDFRogersNLBaynardMDChronic sleep deprivationKrygerMHRothTDementWCPrinciples and Practice of Sleep MedicinePhiladelphiaElsevier Saunders20056776

- HobsonJAPace-SchottEFThe cognitive neuroscience of sleep: neuronal systems, consciousness and learningNat Rev Neurosci2002367969312209117

- RechtschaffenACurrent perspectives on the function of sleepPerspect Biol Med1998413593909604368

- TononiGCirelliCSleep function and synaptic homeostasisSleep Med Rev200610496216376591

- DiekelmannSBornJThe memory function of sleepNat Rev Neurosci20101111412620046194

- MaquetPThe role of sleep in learning and memoryScience20012941048105211691982

- KruegerJMRectorDMRoySVan DongenHPBelenkyGPankseppSleep as a fundamental property of neuronal assembliesNat Rev Neurosci2008991091918985047

- WalkerMPStickgoldRSleep, memory, and plasticityAnnu Rev Psychol20065713916616318592

- BrandSOpwisKHatzingerMHolsboer–TrachslerEREM sleep is related to the transfer of implicit procedural knowledge following metacognitive learningSomnologie201014213220

- CaiDJMednickSAHarrisonEMKanadyJCMednickSCREM, not incubation, improves creativity by priming associative networksProc Natl Acad Sci U S A2009106101301013419506253

- WagnerUGaisSHaiderHSleep inspires insightNature200442735235514737168

- YordanovaJKolevVVerlegerRVerlegerRBornJShifting from implicit to explicit knowledge: different roles of early- and late-night sleepLearn Mem20081550851518626095

- BódizsRKisTLázárASPrediction of general mental ability based on neural oscillation measures of sleepJ Sleep Res20051428529216120103

- ClemensZFabóDHalászPOvernight verbal memory retention correlates with the number of sleep spindlesNeuroscience200513252953515802203

- KirovRUebelHAlbrechtBBanaschewskiTRothenbergerATwo faces of REM sleep in normal and psychopathological developmentEur Psychiatry201126422423

- ManderBASanthanamSSaletinJMWalkerMPWake deterioration and sleep restoration of human learningCurr Biol201121R183R18421377092

- SchabusMHödlmoserKGruberGSleep spindle–related activity in the human EEG and its relation to general cognitive and learning abilitiesEur J Neurosci2006231738174616623830

- SchabusMHoedlmoserKPecherstorferTInterindividual sleep spindle differences and their relation to learning–related enhancementsBrain Res2008119112713518164280

- NishidaMPearsallJBucknerRLWalkerMPREM sleep, prefrontal theta, and the consolidation of human emotional memoryCereb Cortex2009191158116618832332

- WagnerUGaisSBornJEmotional memory formation is enhanced across sleep intervals with high amounts of rapid eye movement sleepLearn Mem2001811211911274257

- WalkerMPThe role of sleep in cognition and emotionAnn N Y Acad Sci2009115616819719338508

- GujarNMcDonaldSANishidaMWalkerMPA role for rem sleep in recalibrating the sensitivity of the human brain to specific emotionsCereb Cortex20112111512320421251

- McNamaraPAndresenJClarkJZborowskiMDuffyCAImpact of attachment styles on dream recall and dream content: a test of the attachment hypothesis of REM sleepJ Sleep Res20011011712711422726

- McNamaraPMcLarenDSmithDBrownAStickgoldRA “Jekyll and Hyde” within: aggressive versus friendly interactions in REM and non-REM dreamsPsychol Sci20051613013615686579

- van der HelmEGujarNWalkerMPSleep deprivation impairs the accurate recognition of human emotionsSleep20103333534220337191

- MikoteitTBrandSBeckJVisually detected NREM Stage 2 sleep spindles in kindergarten children are associated with stress challenge and coping strategiesWorld J Biol Psychiatry Epub ahead of print.

- GujarNYooSSHuPWalkerMPThe unrested resting brain: sleep deprivation alters activity within the default–mode networkJ Cogn Neurosci2010221637164819702469

- ErnstMPineDSHardinMTriadic model of the neurobiology of motivated behavior in adolescencePsychol Med20063629931216472412

- SpearLPThe adolescent brain and age–related behavioral manifestationsNeurosci Biobehav Rev20002441746310817843

- PinyerdBZipfWBPuberty–timing is everything!J Pediatr Nurs200520758215815567

- RomeoRDAdolescence: a central event in shaping stress reactivityDev Psychobiol20105224425320175102

- CaseyBJGetzSGalvanAThe adolescent brainDev Rev200828627718688292

- BlakemoreSJThe developing social brain: implications for educationNeuron20106574474720346751

- BurnettSSebastianCCohen KadoshKBlakemoreSJThe social brain in adolescence: evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging and behavioural studiesNeurosci Biobehav Rev Epub ahead of print.

- WhiteAMUnderstanding adolescent brain development and its implications for the clinicianAdolesc Med State Art Rev200920739019492692

- UhlhaasPJRouxFSingerWHaenschelCSireteanuRRodriguezEThe development of neural synchrony reflects late maturation and restructuring of functional networks in humansProc Natl Acad Sci U S A20091069866987119478071

- SomervilleLHJonesRMCaseyBJA time of change: behavioral and neural correlates of adolescent sensitivity to appetitive and aversive environmental cuesBrain Cogn20107212413319695759

- CompasBEOrosanPGGrantKEAdolescent stress and coping: Implications for psychopathology during adolescenceJ Adolesc1993163313498282901

- KesslerRCBerglundPDelmerOJinRMerikangasKRWaltersEELifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey ReplicationArch Gen Psychiatry20056259360215939837

- PausTKeshavanMGieddJNWhy do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence?Nat Rev Neurosci2008994795719002191

- PostRMLeverichGSXingGWeissRBDevelopmental vulnerabilities to the onset and course of bipolar disorderDev Psychopathol20011358159811523849

- BeesdoKKnappeSPineDSAnxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM–VPsychiatr Clin North Am20093248352419716988

- VarcholLCooperHPsychotherapy approaches for adolescents with eating disordersCurr Opin Pediatr20092145746419455034

- VigodSNStewartDEEmergent research in the cause of mental illness in women across the lifespanCurr Opin Psychiatry20092239640019276809

- RajjiTKIsmailZMulsantBHAge at onset and cognition in schizophrenia: meta-analysisBr J Psychiatry200919528629319794194

- SpearLPHeightened stress responsivity and emotional reactivity during pubertal maturation: Implications for psychopathologyDev Psychopathol200921879719144224

- AngstJCuiLSwendsenJRothenSMajor depressive disorder with subthreshold bipolarity in the National Comorbidity Survey ReplicationAm J Psychiatry20101671194120120713498

- ChangKDCourse and impact of bipolar disorder in young patientsJ Clin Psychiatry201071e0520193644

- LockJFitzpatrickKKAdvances in psychotherapy for children and adolescents with eating disordersAm J Psychother20096328730320131739

- BussingRMasonDMBellLPorterPGarvanCAdolescent outcomes of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a diverse community sampleJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry20104959560520494269

- Chronis-TuscanoAMolinaBSPelhamWEVery early predictors of adolescent depression and suicide attempts in children with attention–deficit/hyperactivity disorderArch Gen Psychiatry2010671044105120921120

- LeckmanJFTourette’s syndromeLancet20023601577158612443611

- BlochMHLeckmanJFClinical course of Tourette syndromeJ Psychosom Res20096749750119913654

- LabergeLPetitDSimardCVitaroFTremblayREMontplaisirJDevelopment of sleep patterns in early adolescenceJ Sleep Res200110596711285056

- McLaughlin CrabtreeVWilliamsNANormal sleep in children and adolescentsChild Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am20091879981119836688

- O’BrienEMMindellJASleep and risk-taking behavior in adolescentsBehav Sleep Med2005311313315984914

- RoffwargHPMuzioJNDementWCOntogenetic development of the human sleep-dream cycleScience196615260461917779492

- TarokhLCarskadonMADevelopmental changes in the human sleep EEG during early adolescenceSleep20103380180920550021

- TaylorDJJenniOGAceboCCarskadonMASleep tendency during extended wakefulness: insights into adolescent sleep regulation and behaviorJ Sleep Res20051423924416120098

- BuchmannARingliMKurthSEEG sleep slow-wave activity as a mirror of cortical maturationCereb Cortex20112160761520624840

- FeinbergICampbellIGSleep EEG changes during adolescence: an index of a fundamental brain reorganizationBrain Cogn201072566519883968

- FeinbergIde BieEDavisNMCampbellIGTopographic differences in the adolescent maturation of the slow wave EEG during NREM sleepSleep20113432533321358849

- KurthSJenniOGRiednerBATononiGCarskadonMAHuberRCharacteristics of sleep slow waves in children and adolescentsSleep20103347548020394316

- RechtschaffenAKalesAA Manual of Standardized Terminology Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages in Human SubjectsUS Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Public Health Service Washington DC US Government Printing Office1968

- AchermannPBorbélyAALow-frequency (<1 Hz) oscillations in the human sleep electroencephalogramNeuroscience1997812132229300413

- SteriadeMNuñezAAmzicaFA novel slow (<1 Hz) oscillation of neocortical neurons in vivo: depolarizing and hyperpolarizing componentsJ Neurosci199313325232658340806

- AserinskyEKleitmanNRegularly occurring periods of eye motility, and concomitant phenomena, during sleepScience195311827327413089671

- CanteroJLAtienzaMStickgoldRKahanaMJMadsenJRKocsisBSleep-dependent theta oscillations in the human hippocampus and neocortexJ Neurosci200323108971090314645485

- ClemensZWeissBSzucsAErossLRásonyiGHalászPPhase coupling between rhythmic slow activity and gamma characterizes mesiotemporal rapid-eye-movement sleep in humansNeuroscience200916338839619555738

- De GennaroLFerraraMSleep spindles: an overviewSleep Med Rev2003742344014573378

- BroughtonRJPolysomnography: principles and applications in sleep and arousal disordersNiedermeyerELopes da SilvaFElectroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications and Related FieldsBaltimoreUrban and Schwarzenberg1987765802

- SintonCMMcCarleyRWNeuroanatomical and neurophysiological aspects of sleep: basic science and clinical relevanceSemin Clin Neuropsychiatry2000561910704534

- BorbélyAAA two process model of sleep regulationHum Neurobiol198211952047185792

- BorbélyAAAchermannPSleep homeostasis and models of sleep regulationJ Biol Rhythms19991455756810643753

- HobsonJASleep is of the brain, by the brain and for the brainNature20054371254125616251949

- GottesmannCNeurophysiological support of consciousness during waking and sleepProg Neurobiol19995946950810515665

- Pace-SchottEFHobsonJAThe neurobiology of sleep: genetics, cellular physiology and subcortical networksNat Rev Neurosci2002359160512154361

- SteigerASleep and the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical systemSleep Med Rev2002612513812531148

- SteigerANeurochemical regulation of sleepJ Psychiatr Res20074153755216777143

- MignotETaheriSNishinoSSleeping with the hypothalamus: emerging therapeutic targets for sleep disordersNat Neurosci20025Suppl1071107512403989

- HiggingsESGeorgeMSThe Neuroscience of Clinical Psychiatry. The Pathophysiology of Behavior and Mental IllnessPhiladelphiaLippincott Williams & Wilkins2007

- McCormickDABalTSleep and arousal: thalamocortical mechanismsAnnu Rev Neurosci1997201852159056712

- SteriadeMTimofeevINeuronal plasticity in thalamocortical networks during sleep and waking oscillationsNeuron20033756357612597855

- HobsonJAMcCarleyRWWyzinskiPWSleep cycle oscillation: reciprocal discharge by two brainstem neuronal groupsScience197518955581094539

- SteriadeMHobsonJNeuronal activity during the sleep-waking cycleProg Neurobiol197661553766996

- LénaIParrotSDeschauxOVariations in extracellular levels of dopamine, noradrenaline, glutamate, and aspartate across the sleep-wake cycle in the medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens of freely moving ratsJ Neurosci Res20058189189916041801

- MontiJMMontiDThe involvement of dopamine in the modulation of sleep and wakingSleep Med Rev20071111313317275369

- RyeDBThe two faces of Eve: dopamine’s modulation of wakefulness and sleepNeurology200463S2S715505137

- KobayashiTGoodCBiedermannJBarnesCSkinnerRDGarcia-RillEDevelopmental changes in pedunculopontine nucleus (PPN) neuronsJ Neurophysiol2004911470148115010495

- KobayashiTGoodCMamiyaKSkinnerRDGarcia-RillEDevelopment of REM sleep drive and clinical implicationsJ Appl Physiol20049673574614527968

- Garcia-RillECharlesworthAHeisterDYeMHayarAThe developmental decrease in REM sleep: the role of transmitters and electrical couplingSleep20083167369018517037

- HatzingerMHemmeterUBrandSIsingMHolsboer-TrachslerEElectroencephalo-graphic (EEG) sleep profiles in treatment course and long-term outcome of major depression: association with DEX/CRH-test responseJ Psychiatr Res20043845346515380395

- CarskadonMAAceboCRegulation of sleepiness in adolescents: update, insights, and speculationSleep20022560661412224839

- CarskadonMAAceboCJenniOGRegulation of adolescent sleep: implications for behaviorDahlRESpearLPAdolescent Brain Development: and OpportunitiesNYNew York Academy of Science2004274291

- HarveyAGA cognitive model of insomniaBehav Res Ther200240886989312186352

- RiemannDSpiegelhalderKFeigeBThe hyperarousal model of insomnia: a review of the concept and its evidenceSleep Med Rev201014193119481481

- RibeiroSMelloCVVelhoTGardnerTJJarvisEDPavlidesCInduction of hippocampal long-term potentiation during waking leads to increased extrahippocampal zif-268 expression during ensuing rapid-eye-movement sleepJ Neurosci200222109141092312486186

- RibeiroSNicolelisMAReverberation, storage, and postsynaptic propagation of memories during sleepLearn Mem20041168669615576886

- MarshallLHelgadóttirHMölleMBornJBoosting slow oscillations during sleep potentiates memoryNature200644461061317086200

- MarshallLKirovRBradeJMölleMBornJTranscranial electrical currents to probe EEG brain rhythms and memory consolidation during sleep in humansPLoS One201162e1690521340034

- WilhelmIDiekelmannSMolzowIAyoubAMölleMBornJSleep selectively enhances memory expected to be of future relevanceJ Neurosci2011311563156921289163

- DiekelmannSBüchelCBornJRaschBLabile or stable: opposing consequences for memory when reactivated during waking and sleepNat Neurosci20111438138621258327

- RaschBBüchelCGaisSBornJOdor cues during slow-wave sleep prompt declarative memory consolidationScience20073151426142917347444

- PeigneuxPLaureysSFuchsSAre spatial memories strengthened in the human hippocampus during slow wave sleep?Neuron20044453554515504332

- MarshallLBornJThe contribution of sleep to hippocampus-dependent memory consolidationTrends Cogn Sci20071144245017905642

- RaschBBornJMaintaining memories by reactivationCurr Opin Neurobiol20071769870318222688

- YordanovaJKolevVWagnerUBornJVerlegerRIncreased alpha 8–12 Hz) activity during slow-wave sleep as a marker for the transition from implicit knowledge to explicit insightJ Cogn NeurosciIn press.

- FogelSMSmithCTLearning-dependent changes in sleep spindles and Stage 2 sleepJ Sleep Res20061525025516911026

- HobsonJAPace-SchottEFStickgoldRDreaming and the brain: toward a cognitive neuroscience of conscious statesBehav Brain Sci200023793842 discussion 904–1121.11515143

- StickgoldRHobsonJAFosseRFosseMSleep, learning, and dreams: off-line memory reprocessingScience20012941052105711691983

- StickgoldRScottLRittenhouseCHobsonJASleep-induced changes in associative memoryJ Cogn Neurosci19991118219310198133

- WalkerMPListonCHobsonJAStickgoldRCognitive flexibility across the sleep–wake cycle: REM-sleep enhancement of anagram problem solvingBrain Res Cogn Brain Res20021431732412421655

- FischerSHallschmidMElsnerALBornJSleep forms memory for finger skillsProc Natl Acad Sci U S A200299119871199112193650

- KarniATanneDRubensteinBSAskenasyJJSagiDDependence on REM sleep of overnight improvement of a perceptual skillScience19942656796828036518

- MaquetPLaureysSPeigneuxPExperience-dependent changes in cerebral activation during human REM sleepNat Neurosci2000383183610903578

- PlihalWBornJEffects of early and late nocturnal sleep on priming and spatial memoryPsychophysiology19993657158210442025

- SmithCTNixonMRNaderRSPosttraining increases in REM sleep intensity implicate REM sleep in memory processing and provide a biological marker of learning potentialLearn Mem20041171471915576889

- RaschBPommerJDiekelmannSBornJPharmacological REM sleep suppression paradoxically improves rather than impairs skill memoryNat Neurosci20091239639718836440

- RaschBGaisSBornJImpaired off-line consolidation of motor memories after combined blockade of cholinergic receptors during REM sleep-rich sleepNeuropsychopharmacology2009341843185319194375

- WalkerMPStickgoldROvernight alchemy: sleep-dependent memory evolutionNat Rev Neurosci.201011218 author reply 218.20168316

- CartwrightRAgargunMYKirkbyJFriedmanJKRelation of dreams to waking concernsPsychiatry Res200614126127016497389

- WagnerUHallschmidMRaschBBornJBrief sleep after learning keeps emotional memories alive for yearsBiol Psychiatry20066078879016806090

- WalkerMPvan der HelmEOvernight therapy? The role of sleep in emotional brain processingPsychol Bull200913573174819702380

- WalkerMPHarveyAGObligate symbiosis: sleep and affectSleep Med Rev20101421521720427211

- CainNGradisarMElectronic media use and sleep in school-aged children and adolescents: A reviewSleep Med20101173574220673649

- GromovIGromovDSleep and substance use and abuse in adolescentsChild Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am20091892994619836697

- GruberRWiebeSTWellsSACassoffJMonsonESleep and academic success: mechanisms, empirical evidence, and interventional strategiesAdolesc Med State Art Rev20102152254121302859

- LofthouseNGilchristRSplaingardMMood-related sleep problems in children and adolescentsChild Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am20091889391619836695

- O’BrienLMThe neurocognitive effects of sleep disruption in children and adolescentsChild Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am20091881382319836689

- OwensJAEtiologies and evaluation of sleep disturbances in adolescenceAdolesc Med State Art Rev20102143044521302853