Abstract

Background

Code status discussion is associated with a decrease in invasive procedures among terminally ill cancer patients. We investigated the association between code status discussion on admission and incidence of invasive procedures, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and opioid use among inpatients with advanced stages of cancer and noncancer diseases.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study in a single center, Ito Municipal Hospital, Japan. Participants were patients who were admitted to the Department of Internal Medicine between October 1, 2013 and August 30, 2015, with advanced-stage cancer and noncancer. We collected demographic data and inquired the presence or absence of code status discussion within 24 hours of admission and whether invasive procedures, including central venous catheter placement, intubation with mechanical ventilation, and CPR for cardiac arrest, and opioid treatment were performed. We investigated the factors associated with CPR events by using multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Results

Among the total 232 patients, code status was discussed with 115 patients on admission, of which 114 (99.1%) patients had do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders. The code status was not discussed with the remaining 117 patients on admission, of which 69 (59%) patients had subsequent code status discussion with resultant DNR orders. Code status discussion on admission decreased the incidence of central venous catheter placement, intubation with mechanical ventilation, and CPR in both cancer and noncancer patients. It tended to increase the rate of opioid use. Code status discussion on admission was the only factor associated with the decreased use of CPR (P<0.001, odds ratio =0.03, 95% CI =0.004–0.21), which was found by using multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Conclusion

Code status discussion on admission is associated with a decrease in invasive procedures and CPR in cancer and noncancer patients. Physicians should be educated about code status discussion to improve end-of-life care.

Introduction

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is the default standard of care in hospitals after cardiopulmonary arrest unless a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order is written with the consent of the patient.Citation1–Citation3 In the USA, physicians are required to discuss and officially order a code status when patients are admitted to a hospital.Citation3 In contrast, this practice is not obligatory in Japan. Even in the case of patients with an advanced stage of disease, some doctors discuss code status on admission and others do not. Consequently, we often observe inappropriate CPR for terminally ill inpatients in Japan, whereas some physicians do not perform CPR without discussing the code status with patients if it appears to be futile or inappropriate. No previous studies have reported whether code status discussion on admission decreases the use of invasive procedures and CPR among inpatients with advanced stages of illness in Japan. Several studies have found that end-of-life discussion decreases invasive treatments among terminal cancer patients.Citation4–Citation7 In patients who died on an oncology ward, code status documentation within 48 hours of admission was associated with less aggressive end-of-life care, regardless of the reason for admission.Citation4 However, it has not yet been elucidated whether code status discussion on admission decreases CPR and invasive procedures among inpatients with advanced stages of diseases other than cancer. Therefore, we investigated the association of code status discussion on admission with aggressive procedures among patients with not only advanced-stage cancer, but also noncancer diseases.

Methods

Ethical approval

The study protocol for this retrospective cohort study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ito Municipal Hospital, Shizuoka, Japan. Informed consent from each patient was waived by the Ethics Committee because we used only retrospective de-identified patient data.

Study population

Study participants were patients who had been admitted to Ito Municipal Hospital between October 1, 2013, and April 30, 2015, with advanced stages of diseases. Ito Municipal Hospital serves a population of 70,000 patients; ~4,000 patients are admitted to this hospital per year, with approximately half of them admitted to surgical units and half to internal medicine units. Most internal medicine patients are treated by general internists. The hospital does not have a palliative care service; therefore, internists perform palliative care by themselves. Advanced-stage cancer was defined by a score of <70 points on the Palliative Performance Scale.Citation8 The advanced stages of various other diseases were defined according to a previous report, which describes the characteristics of noncancer presentations with a median survival of ≤6 months ().Citation9 Patients who died in the emergency room were excluded.

Table 1 Presentations associated with a median survival of ≤6 months, with effect of treatments on survival

Data collection

Data were collected by a retrospective review of electronic health charts. We collected age, sex, activities of daily livings (ADLs), and comorbidities. We calculated ADLs by using the Katz index, excluding the factor of incontinence, with a maximum score of 5 (independent) and minimum score of 0 (very dependent).Citation10 “Presence of code status discussion on admission” was defined as a documentation of a physician asking the patients their preference regarding life-prolonging treatment, including intubation with mechanical ventilation and electrical cardioversion for non–cardiac arrest events and CPR for cardiac arrest events, within 24 hours after admission. Whether these procedures as well as central venous catheter placement were actually performed during hospitalization was recorded, along with the information about opioid prescriptions. Data regarding the length of hospital stay were also collected.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as medians (inter-quartile range), and discrete variables were summarized as percentages. Continuous variables were analyzed and compared by using the Mann–Whitney U-test, and dichotomous variables were analyzed and compared by using the χ2 test.

The influence of code status discussion, on admission, on the incidence of high-burden invasive procedures, including central venous catheter placement, intubation with mechanical ventilation, and CPR, as well as opioid treatment, was evaluated by using χ2 test among patients stratified into cancer and noncancer groups. Factors associated with the incidence of CPR were analyzed by using multivariate logistic regression analysis. IBM® SPSS® software Version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform the statistical analysis. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

In total, 318 patients died in our hospital during the study period. We excluded 86 patients because 66 patients died in the emergency room and 20 patients did not meet the criteria of advanced-stage disease. Ultimately, 232 patients were included in this study. Code status was discussed on admission with 115 patients and not discussed with the remaining 117 patients. presents the characteristics of these two groups. There were no significant differences in age, sex, or ADLs. Among cancer patients (n=97), 56 (67%) of them had code status discussion on admission, whereas among non-cancer patients (n=135), 59 (44%) of them had code status discussion on admission (P<0.05). The incidence of code status discussion on admission for each primary diagnosis was as follows: liver disease (6 of 14, 43%; P=0.223), heart disease (5 of 24, 21%; P<0.01), renal disease (0 of 2, 0%; P=0.186), cerebrovascular disease (3 of 3, 100%; P=0.201), lung disease (6 of 26, 23%; P<0.01), and geriatric syndrome or dementia (39 of 66, 53%; P=0.63); (P-values in comparison with the cancer group).

Table 2 Patient characteristics

Incidence rate of code status discussion and CPR

On admission, 115 (49.6%) of 232 patients had a code status discussion with their physicians, of which 114 (99.1%) patients had DNR orders and 1 (0.9%) patient had CPR without a DNR order (full code). Of the remaining 117 (50.4%) patients who did not have a code status discussion on admission, 69 (59.0%) patients had code status discussion and conveyed DNR orders during hospitalization. Among the remaining 48 patients with whom code status was never discussed, 32 (27.0%) of 117 patients received CPR due to the absence of DNR orders, and 16 (13%) of 117 patients did not receive CPR despite the absence of a documented code status discussion or DNR orders.

Presence of code status discussion, life-prolonging procedures, length of stay, and opioid use

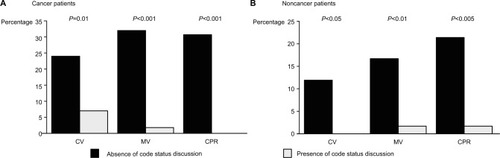

The absence of code status discussion on admission significantly increased the incidence of central venous catheter placement (3.5% vs. 19.7%, P<0.001, odds ratio [OR] =5.65, 95% CI =2.01–15.8), intubation with mechanical ventilation (1.7% vs. 26.5%, P<0.001, OR =15.2, 95% CI =3.7–62.1), and CPR (0.9% vs. 27.4%, P<0.001, OR =31.5, 95% CI =4.3–226.4). Similar trends were observed in both cancer patients and noncancer patients (). The median length of stay was not statistically different between patients who did and did not have a code status discussion (17 days [10, 34] vs. 17 days [9, 30], respectively, P=0.895). Code status discussion on admission tended to increase the rate of opioid use (40% vs. 28%, P=0.072, OR =1.2, 95% CI =0.99–1.44).

Figure 1 Incidence of invasive procedures and cardiopulmonary resuscitation among cancer patients (A) and noncancer patients (B) in the presence and absence of code status discussion on admission.

Factors associated with the incidence of CPR

CPR was performed in 33 (14%) of 232 patients. shows the factors associated with CPR. In a multivariate analysis including 5 factors (ie, age >75 years, primary diagnosis of cancer, pulmonary disease, geriatric syndrome or dementia, and code status discussion), only the presence of code status discussion on admission was significantly associated with the decreased incidence of CPR (P<0.005, OR =0.03, 95% CI =0.004–0.21).

Table 3 Factors associated with CPR

Discussion

In this study, physicians did not discuss code status with about half of the patients on admission although they were with advanced stages of diseases. It has been reported that code status discussion on admission decreases invasive treatment among terminal cancer patients.Citation4–Citation7 This study is the first to show that code status discussion on admission is significantly associated with the reduction of invasive procedures and CPR among both cancer and noncancer patients. This study also demonstrated that code status discussion on admission tended to increase the use of opioids, which may indicate better quality of care in our study population.

Currently, CPR is the default standard of care after cardiopulmonary arrest unless a DNR order is written with the consent of the patient,Citation1,Citation2 even in the end stage of illness.Citation3 According to the recommendation by the Joint Commission, all hospitals and medical institutions are required to have formal procedures for discussing, documenting, and implementing DNR orders.Citation3 Similar recommendations have been made by the American Society of Clinical OncologyCitation11 and the American Medical Association.Citation1 Legally, the US Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990 requires hospitals, nursing homes, health maintenance organizations, and hospices that participate in Medicare and Medicaid to ask whether the patient has an advance directive, to provide information about them, and to incorporate advance directives into the medical record.Citation12 The American College of Physicians encourages physicians to routinely raise the topic of advance planning with patients who have decision-making capacity and encourage them to review their values and preferences with their surrogates and family members before an acute crisis.Citation13 In spite of these guidelines and law, ~80%–90% of inpatients reportedly did not have a code status discussion even in the USA.Citation14,Citation15

In Japan, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare established a guideline for the decision-making process for end-of-life care in 2007, which was updated in 2015.Citation16 The Guideline stresses the importance of not only the patients’ medical condition, but also their values and preferences in the decision-making process.Citation16 In our study, DNR order was discussed with only 50% of patients on admission, although they were with an advanced stage of disease. A survey conducted by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in 2013 found that ~70% of respondents would not like to have invasive treatment if they become terminally ill and ~70% would like to establish advance directives, although only 3% of them had.Citation17 In another survey of middle-aged and older adults in Tokyo, Japan, 60% of respondents stated that they would like to express their wishes regarding advance directives, but <10% had already done so.Citation18 Therefore, physicians can play a role in helping patients to express their values and preferences regarding end-of-life issues, especially when they are with advanced stages of disease.

As patients approach death, physicians must consider treatments to improve the quality of dying and death, focusing on palliative care, quality of life, and patient and family satisfaction rather than prolonging life.Citation19,Citation20 In terms of palliative care for patients with advanced stages of illness, a holistic approach should be adopted, including end-of-life discussion; assessment and treatment of symptoms; psychological, spiritual, and bereavement support; and coordination of care.Citation21 End-of-life communication should begin with establishing the goal of care.Citation21 Communication of prognosis is also important. Without these discussions, physicians often fail in discussing the decision to withhold or withdraw aggressive care. Although physicians may worry that disclosing a realistic prognosis might make patients depressed and cause them to lose hope or that involving palliative care may reduce survival, several reports have demonstrated the opposite.Citation22 Some patients wish to receive invasive treatment solely because they lack a full understanding of their own prognosis.Citation22,Citation23 It was reported that prognostic disclosures are associated with more realistic patient expectations of life expectancy, without decrements to their emotional well-being or the patient–physician relationship among patients with advanced-stage solid malignancies.Citation24 Having a realistic expectation of life expectancy was also associated with DNR orders.Citation24 CPR has been reported to decrease the quality of life among patients with advanced-stage cancer,Citation25–Citation28 while having a low probability of resuscitation of cardiopulmonary functions or hospital discharge for terminal cancer patients.Citation29 End-of-life discussion was associated with a decrease in invasive procedures, including central venous catheter placement, intubation with mechanical ventilation, CPR, and increase in opioid use in this study. These changes in clinical practice could potentially decrease the medical cost and grief of the family and improve the quality of life, as previously reported.Citation7,Citation30 In a report, among 12 terminally ill cancer patients in whom initial code status discussion shortly after admission resulted in full code, all of them changed their status to DNR after being fully informed of their prognosis before cardiopulmonary arrest.Citation4 This may indicate that early code status discussions resulting in full code orders may also provide patients and surrogate decision-makers the time to consider less aggressive end-of-life care and reconsider DNR orders.Citation4 To decrease the rate of undesired CPR, it is necessary to learn appropriate prognostication and prognosis communication skills and initiate code status discussion in the early phase of advanced-stage disease. Education concerning code status is necessary in all hospitals in Japan as it faces a super-aging society.Citation31,Citation32

Notably, our study demonstrated that code status discussion also decreased the incidence of CPR and invasive procedures in patients with noncancer diseases. Furthermore, code status discussion occurred on admission more frequently for patients with a primary diagnosis of cancer than for noncancer patients, more specifically those with cardiac and pulmonary diseases in our study, which is consistent with the result of a previous study.Citation14 In case of chronic heart failure or pulmonary disease, patients’ health status declines slowly with occasional acute exacerbation, from which they often recover.Citation33,Citation34 In contrast, patients with the advanced stage of cancer have a more predictable progressive downward trajectory with clear prognosis.Citation33,Citation35 Therefore, it is more challenging to estimate the prognosis of chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease than that of cancer.Citation33 It was reported that physicians often avoided end-of-life discussion with patients with heart failure for fear of causing alarm and destroying hope.Citation36 As a result, end-of-life discussion is often deferred until more emergent and less favorable occasions. Although heart failure has a poorer prognosis than many cancers, patients with heart failure establish DNR orders later in the disease course and receive more life-sustaining treatments, including CPR, than cancer patients.Citation37 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease has a similar situation to heart failure.Citation38 Consequently, these patients often have little idea on their prognosis and may have unrealistically optimistic expectations of their prognosis.Citation39,Citation40 Physicians should not delay the initiation of end-of-life discussions with patients with advanced-stage cancer as well as noncancer diseases to provide better quality of care.

Our study has several limitations. First, this study was conducted in a single center; therefore, the results cannot be extrapolated to other hospitals in Japan or to other countries. Second, because of the nature of a retrospective chart review, it is not possible to determine whether the decrease in invasive procedures resulted from code status discussion itself or from a tendency for physicians who have code status discussions with patients in their daily practice to withhold invasive procedures in terminal situations. Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that the patients with a poorer prognosis, for whom invasive procedures or CPR was obviously more inappropriate, were more likely to have a code status discussion in advance; therefore, the presence of code status discussion might be simply an indicator of poorer prognosis. However, the finding that the presence or absence of code status discussion on admission was not associated with a statistical difference in patients’ length of hospital stay before death suggests that the two groups had similar prognoses. Nonetheless, we believe that our study highlights the importance of code status discussions in hospital settings to avoid unnecessary invasive procedures or CPR in cases of terminal illness.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that code status discussion was associated with a decrease in CPR and other high-burden invasive procedures. It also was associated with a trend for increased use of opioids among patients with advanced stages of various diseases.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

This research was not funded by any source.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Guidelines for the appropriate use of do-not-resuscitate ordersCouncil on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, American Medical AssociationJAMA1991265186818712005737

- Optimum care for hopelessly ill patientsA report of the Clinical Care Committee of the Massachusetts General HospitalN Engl J Med1976295362364934224

- LoertscherLReedDABannonMPMuellerPSCardiopulmonary resuscitation and do-not-resuscitate orders: a guide for cliniciansAm J Med20101234920102982

- CaissieAKevorkNHannonBLeLWZimmermannCTiming of code status documentation and end-of-life outcomes in patients admitted to an oncology wardSupport Care Cancer20142237538124077686

- MackJWCroninAKeatingNLAssociations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: a prospective cohort studyJ Clin Oncol2012304387439523150700

- BradleyEHHallemeierAGFriedTRDocumentation of discussions about prognosis with terminally ill patientsAm J Med200111121822311530033

- WrightAAZhangBRayAAssociations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustmentJAMA20083001665167318840840

- AndersonFDowningGMHillJCasorsoLLerchNPalliative performance scale (PPS): a new toolJ Palliat Care199612511

- SalpeterSRLuoEJMalterDSStuartBSystematic review of non-cancer presentations with a median survival of 6 months or lessAm J Med2012125512.e1512.e622030293

- KatzSFordABMoskowitzRWJacksonBAJaffeMWStudies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial functionJAMA196318591491914044222

- WallingALorenzKADySMEvidence-based recommendations for information and care planning in cancer careJ Clin Oncol2008263896390218688058

- GrecoPJSchulmanKALavizzo-MoureyRHansen-FlaschenJThe Patient Self-Determination Act and the future of advance directivesAnn Intern Med19911156396431892335

- SnyderLAmerican College of Physicians, Ethics Professionalism, and Human Rights CommitteeAmerican College of Physicians Ethics Manual: sixth editionAnn Intern Med20121567310422213573

- AuerbachADKatzRPantilatSZFactors associated with discussion of care plans and code status at the time of hospital admission: results from the Multicenter Hospitalist StudyJ Hosp Med2008343744519084893

- HofmannJCWengerNSDavisRBPatient preferences for communication with physicians about end-of-life decisions. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preference for Outcomes and Risks of TreatmentAnn Intern Med19971271129214246

- Guideline: decision making process of end of life medical careJapanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (in Japanese)2015 Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/iryou/saisyu_iryou/index.htmlAccessed January 3, 2017

- Survey of the general public’s attitudes toward end of life treatmentMinistry of Health, Labour and Welfare (in Japanese)2014 Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi/0000042968.htmlAccessed January 3, 2017

- MiyataHShiraishiHKaiISurvey of the general public’s attitudes toward advance directives in Japan: how to respect patients’ preferencesBMC Med Ethics20067E1117044943

- PatrickDLEngelbergRACurtisJREvaluating the quality of dying and deathJ Pain Symptom Manage20012271772611532585

- DonaldsonMSFieldMJMeasuring quality of care at the end of lifeArch Intern Med19981581211289448550

- MorrisonRSMeierDEClinical practice. Palliative careN Engl J Med20043502582259015201415

- MackJWSmithTJReasons why physicians do not have discussions about poor prognosis, why it matters, and what can be improvedJ Clin Oncol2012302715271722753911

- WeeksJCCookEFO’DaySJRelationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferencesJAMA1998279170917149624023

- EnzingerACZhangBSchragDPrigersonHGOutcomes of prognostic disclosure: associations with prognostic understanding, distress, and relationship with physician among patients with advanced cancerJ Clin Oncol2015333809381626438121

- EarleCCParkERLaiBWeeksJCAyanianJZBlockSIdentifying potential indicators of the quality of end-of-life cancer care from administrative dataJ Clin Oncol2003211133113812637481

- EarleCCLandrumMBSouzaJMNevilleBAWeeksJCAyanianJZAggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: is it a quality-of-care issue?J Clin Oncol2008263860386618688053

- GrunfeldELethbridgeLDewarRTowards using administrative databases to measure population-based indicators of quality of end-of-life care: testing the methodologyPalliat Med20062076977717148531

- BarberaLPaszatLChartierCIndicators of poor quality end-of-life cancer care in OntarioJ Palliat Care200622121716689410

- ReisfieldGMWallaceSKMunsellMFWebbFJAlvarezERWilsonGRSurvival in cancer patients undergoing in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a meta-analysisResuscitation20067115216016987581

- ZhangBWrightAAHuskampHAHealth care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversationsArch Intern Med200916948048819273778

- AraiHOuchiYTobaKJapan as the front-runner of super-aged societies: perspectives from medicine and medical care in JapanGeriatr Gerontol Int20151567368725656311

- McCurryJJapan will be model for future super-ageing societiesLancet2015386152326530607

- MurraySAKendallMBoydKSheikhAIllness trajectories and palliative careBMJ20053301007101115860828

- AllenLAStevensonLWGradyKLDecision making in advanced heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart AssociationCirculation20121251928195222392529

- LunneyJRLynnJFoleyDJLipsonSGuralnikJMPatterns of functional decline at the end of lifeJAMA20032892387239212746362

- BarclaySMomenNCase-UptonSKuhnISmithEEnd-of-life care conversations with heart failure patients: a systematic literature review and narrative synthesisBr J Gen Pract201161e49e6221401993

- TanvetyanonTLeightonJCLife-sustaining treatments in patients who died of chronic congestive heart failure compared with metastatic cancerCrit Care Med200331606412544994

- PatelKJanssenDJCurtisJRAdvance care planning in COPDRespirology201217727822008225

- HoleBSalemJHow long do patients with chronic disease expect to live? A systematic review of the literatureBMJ Open20166e012248

- AllenLAYagerJEFunkMJDiscordance between patient-predicted and model-predicted life expectancy among ambulatory patients with heart failureJAMA20082992533254218523222