Abstract

Late-life depression (LLD) is both a prevalent and life-threatening disorder, affecting up to 13.3% of the elderly population. LLD can be difficult to identify because patients mainly consult their general practitioner (GP) for somatic complaints. Moreover, patients may be hesitant to express the problem to their GP. Increased vigilance on the part of the GP can only benefit older people with depression. To recognize the risk of LLD, screening tools are provided in addition to treatment options for LLD. This review aims to provide the GP with guidance in recognizing and treating LLD. It tries to connect mainstream etiologies of LLD (e.g., vascular, inflammation, hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis) with risk factors and current therapies. Therefore, we provide a basis to the GP for decision-making when choosing an appropriate therapy for LLD.

Introduction

Late-life depression (LLD), with an estimated prevalence of 13.3%, is a common mental health disorder in older people.Citation1 It is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in addition to a high societal cost.Citation2 Moreover, the treatment cost of an older person with depression is 1.86 times higher than that of an older person without depression.Citation3 The consequences of untreated LLD include poor quality of life, exacerbation of chronic illnesses, and suicide.Citation4 Due to the atypical presentation, the diagnosis is often missed by general practitioners (GPs), which consequently leads to undertreatment of the disease.Citation5 However, an LLD diagnosis in time can be life-saving and, when treated, LLD has a good prognosis; up to 70% of older patients with depression treated with antidepressants recover from a depressive episode.Citation6 The aim of this review is to provide a comprehensive and practical guide for GPs with regard to the main risk factors as well as the diagnostic and therapeutic approach to LLD.

Definition of the problem

LLD can be defined as depression that occurs for the first time after age 60. When we use the term “depression”, we refer to major depressive disorder as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 (DSM-5). The cardinal symptoms of major depressive disorder are anhedonia (a loss of interest in activities one used to enjoy) and a depressed mood through most of the day.Citation7 According to the DSM 5, an older person has an episode of major depression if he or she has at least one cardinal symptom and four or more of the following symptoms for at least 2 weeks: significant decrease or increase in weight or appetite; insomnia or hypersomnia, fatigue, psychomotor agitation, or retardation; diminished ability to concentrate or make decisions; feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt; and recurrent thoughts of death or suicidal ideation. In the elderly, depressive feelings may often be masked by unexplained physical complaints (e.g., fatigue, diffuse pain or back pain, headache, chest pain, etc.) and, consequently, the classical DSM 5 criteria sometimes seem to fail in terms of diagnosing depression in elders.Citation8

Furthermore, the conditions mentioned above can exist concomitantly. The differential diagnosis of LLD is broad (). Physical examination and cognitive screening may be useful in ruling out common conditions that are often confused with depression and in assessing for commonly co-occurring diseases. Consequently, a thorough medical history, Mini Mental State Exam, physical examination, and, sometimes, further technical investigations are recommended. Indications for referring patients to a geriatric psychiatrist are presented in .Citation8

Table 1 Differential diagnosis of late-life depression

Table 2 Summarizing table

A particularly difficult differential diagnosis of LLD is dementia (see ). Moreover, Parkinson disease (PD) is a prevalent neurodegenerative disease associated with depression and occurs in up to 35% of patients with PD.Citation10 Depression associated with PD is not a single entity, but rather a heterogeneous group of three subtypes where only one group is directly related to the pathophysiology of PD.Citation11 The signs of depression linked to PD include nonresponse to at least one course of antidepressant treatment, absence of suicidal behavior, absence of guilt and self-blame, and no personal history of depression. The pathophysiological mechanism of depression in PD is unknown, but a current hypothesis implies genetic factors, Lewy body pathology, stress-induced hypercortisolemia, inflammation, psychosocial aspects, and changes in monoaminergic signaling.Citation10

Table 3 Differential diagnosis: late-life depression versus dementia

In the assessment of LLD, exclusion of somatic causes of depression through patient history, clinical examination, laboratory tests, and/or imaging is the first step in appraising LLD.Citation12 A GP who has good knowledge of the patient’s personality can identify nonverbal cues and changes in behavior suspicious for mood problems.Citation13 In addition, information from family members and/or caregivers on the patient’s mood, functioning and behavior is crucial for assessing the older person with depression.

There is no golden standard for bringing up depression; it is dependent on the physician’s manner, and research on the topic is lacking. To engage the patient, the use of the bio-psychosocial model may be helpful: inform the patient that the illness is an interaction between physiological (e.g. serotonin hypothesis), psychological, and social factors.Citation14

Risk factors

The risk factors for LLD are a combination of biological and psychosocial factors.

Biological risk factors

The biological risk factors associated with LLD are old age and female sex.Citation15 In addition, there may be a genetic vulnerability, making some people more susceptible to LLD than others.Citation16

Patients with poor physical health (e.g. multiple comorbidities, sleeping disorders, etc.) may be predisposed to LLD.Citation17 These people often use more medication, which in itself is a risk factor for LLD.Citation18

The concept of frailty stresses a loss of function in several domains of functioning (not only the physical), leading to a decline in the reserve capacity for dealing with stressors. Frailty can be defined by the Fried criteria: weight loss, decreased handgrip strength, slowness, exhaustion, and low physical activity.Citation19 Physical frailty is linked to chronic inflammation and LLD.Citation20,Citation21 Poor nutritional status is associated with frailty; therefore, nutritional supplements (vitamin D and proteins) could benefit the depressed frail patient.Citation22 Nutritional deficits that are often reported in older people with depression are vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies.Citation23 The current hypothesis states that vitamin D affects mood by interacting with brain receptors in the limbic structures and hippocampus.Citation24

Neurodegenerative disease (e.g., PD or Alzheimer) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) has also been considered a possible risk factor for LDD.Citation25 There are hypotheses that LLD may lead to MCI and, consequently, dementia.Citation25 The debate is still ongoing, and the current literature is inconclusive about LLD being a prodrome of dementia.Citation27 What we do know is that LLD and dementia frequently co-occur, and depression can be the first sign of dementia.Citation28,Citation29

The vascular hypothesis states that cerebrovascular disease may cause or predispose to LLD. The concept of vascular depression as a clinical entity is inherently linked to this hypothesis and can be explained by reduced cerebral perfusion, altered brain connectivity due to vascular brain lesions, and chronic low-grade inflammation.Citation30 LLD has been linked to atherosclerosis, which is – at the same time – the leading cause of coronary heart disease.Citation31

Psychosocial risk factors

Kaji et al point out that psychological factors such as loss of purpose in life or human relationships seem to be associated with LLD.Citation32 Moreover, lower education has been linked to LLD.Citation33 Being a widower or single is a risk factor for LLD, but possibly reflects the fact that loneliness, lack of social support, and stressful life events or poverty are the risk factors for depression in old age.Citation34 Being functional or visually impaired increases the risk of developing LLD.Citation35

Poor lifestyle habits can put elders at risk for LLD. Both smoking and alcohol use are the risk factors of LLD.Citation18 In addition, the use of sleep medication has been linked to LLD, but sleep disturbance in general is a risk factor for LLD.Citation35

Screening

In the following text, we only discuss screening tools validated in a geriatric and primary care setting. These tools should not be used systematically; rather, an opportunistic screening is advised in patients in whom LLD is suspected. In , we compare the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), and Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2).

Table 4 Comparison of validated screening tools for late-life depression in primary care

Approach

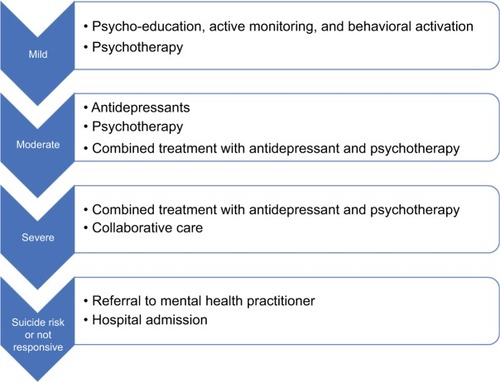

The recommended approach to LLD is stepped care: treatment is based on the severity of depression and preference of the.Citation42 The severity of the depressive disorder (mild, moderate, or severe) is based on the number of symptom criteria, the severity of those symptoms, and their functional disability in the DSM-5. If the selected treatment for LLD is inadequate, the GP should step up and provide the next step of treatment (see ). A summary of risk factors, screening tools, and interventions are provided in .

Prevention

The risk factors that can be modified are nutritional deficiencies and cardiovascular disease, which are more common at older ages.Citation43,Citation44

Vascular risk factors can be improved by exercise, diet, smoking cessation as well as treatment for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and hyperglycemia.Citation45,Citation46 These inter ventions reduce the further progression of atherosclerosis and prevent diabetes and cerebrovascular disorders – all of which are linked to LLD.Citation45,Citation47

Nutritional supplementation, such as a high dose of vitamin D (2,000 IU daily), folic acid (800 µg–2 mg), and a high-protein diet (for frail elders), for a deficiency of vitamins or folic acid in older people (including the frail) with depression has been suggested to alleviate depressive symptoms.Citation22,Citation24,Citation48

Nonpharmacological treatment

Psycho-education

The GP plays a central role in providing psycho-education: to clarify major depressive disorder, to explain therapeutic options, discuss biopsychological vulnerability, to teach to recognize warning signs, and to inform and support the spouse.Citation49 In addition, the primary physician actively monitors the patient through frequent visits. Moreover, the primary physician tries to provide a structure in the patient’s life and activate the patient through structured and fun activities.Citation50 The structure provided must be manageable for the patient and should lead to positive feelings. A balance between tasks and relaxation is essential. Healthy food, sufficient sleep, and daily interactions are a prerequisite.

Behavioral activation

Structured physical activity is recommended for older people with mild or moderate depression who are physically capable and can be motivated to exercise.Citation51 Exercise is safe and effective in addition to the pharmacological treatment of depression.Citation51 Mere referral of an older person with depression is not enough.Citation52 Primary care physicians and psychiatrists should take an active role in keeping the patient motivated and managing the exercise-related adverse effects.Citation53 A recent meta-analysis recommends structured, supervised exercise programs, three times a week (45–60 min), over 10–14 weeks, and at low intensity for mild to moderate depression.Citation51

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy is the most important type of nonpharmacological treatment. In LLD, psychotherapy decreases depressive symptoms in older people with depression.Citation54 Psychotherapeutic interventions can prevent LLD in older people with sub-syndromal depressionCitation55 and are not inferior to pharmacological treatment.Citation56 Evidence-based psychotherapeutic treatments of depression in older adults include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), problem-solving therapy (PST), reminiscence therapy, and interpersonal therapy (IPT).Citation57 One relatively new therapy is life review therapy, where the patient shares and talks about important life events and memories with their therapist. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) proved that life review therapy is effective in depressed older adults and also reduces anxiety.Citation58 In addition, life review therapy has already been implemented with success in a structured multidisciplinary approach in nursing homes and led to reduced prevalence of depression.Citation50

Pharmacological treatment

Older adults have different pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics due to age-related physiological changes.Citation59 Medication must be administered at lower doses or slowly titrated while actively monitoring the patient.Citation60 Patients with comorbidities usually take multiple drugs. Increased vigilance for drugs interactions is, therefore, necessary.Citation61 A careful review of the patient’s drug history is recommended. Moreover, when choosing a psychotropic drug, one needs to keep track of the drug’s safety profile. Because falls can invalidate old adults and even lead to increased mortality (hip fracture), avoid medications that sedate the patient.Citation62,Citation63

In primary care, both tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the pharmacological treatments of choice.Citation64 Existing evidence suggests that no one class of antidepressant drugs has been found to be more effective than another in the treatment of LLD.Citation65 Although newer antidepressants are not more effective than older ones, they are better tolerated and are safer, especially in cases of overdose.Citation60 The adverse effect data suggest the modest superiority of SSRIs over TCAs.Citation66 When choosing an SSRI, slight preference goes to an SSRI with the least known drug interactions such as sertraline or (es) citalopram. Citalopram has a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) black-box warning for increased risk of arrhythmia (QTc prolongation), which is why sertraline is preferred over citalopram.Citation67 TCAs are as effective as SSRIs for LLD, but are less often used because of frequent side effects.Citation68 TCAs with lesser anticholinergic side effects, such as nortriptyline, are recommended by the authors. Both SSRIs and TCAs are associated with fracture risk, although causality is not proven.Citation69

Serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs; e.g., duloxetine, venlafaxine) are an alternative to SSRIs for depressed older adults when SSRIs are ineffective or contraindicated.Citation70,Citation71 SNRIs are not only effective against the major depressive disorder but also effective in the treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain.

Another second-generation antidepressant that can be used as an alternative for SSRIs is mirtazapine. The sedative side effects of mirtazapine are used as a treatment for insomnia.Citation72 In addition, mirtazapine improves the appetite and can be used for anorexia.Citation73 The effect of mirtazapine on sodium levels is limited, and therefore, less hyponatremia is noted in patients taking mirtazapine.Citation74

Important and frequent side effects and contraindications of antidepressants are reported in .

Table 5 Side effects and relative contraindications of antidepressant treatment

Electroconvulsive therapy

An effective treatment for LLD, available from mental health specialists, is electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). In ECT, an electrical stimulus is given for a brief period to produce a generalized seizure. Multiple RCTs have proved that ECT is beneficial for LLD, especially psychotic depression, treatment-refractory depression, catatonia, and depression with severe weight loss and anorexia.Citation75,Citation77 ECT is an effective and safe treatment for depression in adults, including the oldest elders (≥80 years).Citation77 Recent evidence suggests old age is a positive predictor of response to ECT: it gives faster and higher remission rates as compared to antidepressants.Citation78 A meta-analysis of the cognitive effects of ECT suggests its relative safety and the transient character of its effects on memory.Citation79 Autobiographical memory is affected by ECT, but restored or improved 6 months after treatment.Citation80 Compared to antidepressants, ECT induces a higher speed of remission.Citation81

Multidisciplinary approach

A multidisciplinary approach to LLD can be achieved through a collaborative care model. Collaborative care was designed in the United States for patients with (chronic) depression, wherein the GP who cares for a depressed elder is supported by a care manager and a multidisciplinary team comprising a psychiatrist and nurses. In this model, there is a shared responsibility of the depressed patient and the patient can benefit from different albeit synergistic approaches of LLD. Collaborative care is more effective than the standard care by GPs and was successfully tested in the United States, England, and the Netherlands.Citation82–Citation85 In general practice, the patient and his close family members can be invited once or twice a year to a “home meeting”. Those present at these meetings are the most relevant caregivers: the physiotherapist, the social worker, the home nurse, the occupational therapist, and the GP. In this meeting, the patient can express his\her needs, whereas the other members can balance what’s going well with what can improve the treatment of the patient. These recommendations then guide the treatment plan. If deemed necessary, the patient can be extensively investigated in a geriatric day-care hospital. In a few cases of severe and recurrent depression, a case manager (e.g., working in a geriatric psychiatric clinic) can be asked to coordinate the implementation of the defined treatment plan.

Conclusion

LLD is a prevalent disease that often presents with atypical symptoms and more somatic (co)morbidities and complaints. A stepped care model to treat depression is advised, taking into account the severity of the depression. Due to the somatic co(morbidities), a collaborative care model is preferred. The collaborative care model has proven efficacy and cost-effectiveness in LLD.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BeekmanATCopelandJRPrinceMJReview of community prevalence of depression in later lifeBr J Psychiatry1999174430731110533549

- BlazerDGDepression in late life: review and commentaryJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2003583M249M265

- BockJOBrettschneiderCWeyererSExcess health care costs of late-life depression – results of the AgeMooDe studyJ Affect Disord201619913914727104802

- UnützerJClinical practice. Late-life depressionN Engl J Med2007357222269227618046030

- MitchellAJRaoSVazeADo primary care physicians have particular difficulty identifying late-life depression? A meta-analysis stratified by agePsychother Psychosom201079528529420616623

- BottinoCMBarcelos-FerreiraRRibeizSRTreatment of depression in older adultsCurr Psychiatry Rep201214428929722627999

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®)American Psychiatric PublishingWashington, DC2013

- GreensteinSPMcGonigleDKellnerCHLate life depressionSimonABNewASGoodmanWKMount Sinai Expert Guides: PsychiatryChichester, West SussexJohn Wiley & Sons, Ltd2017312321

- FountoulakisKNO’HaraRIacovidesAUnipolar late-onset depression: a comprehensive reviewAnn Gen Hosp Psychiatry2003211114675492

- AarslandDPåhlhagenSBallardCGEhrtUSvenningssonPDepression in Parkinson disease – epidemiology, mechanisms and managementNat Rev Neurol2012813547

- EvenCWeintraubDIs depression in Parkinson’s disease (PD) a specific entity?J Affect Disord2012139210311221794923

- GloverJSrinivasanSAssessment of the person with late-life depressionPsychiatr Clin North Am201336454556024229656

- WittinkMNBargFKGalloJJUnwritten rules of talking to doctors about depression: integrating qualitative and quantitative methodsAnn Fam Med20064430230916868233

- MilesEBiopsychosocial modelGellmanMDTurnerJREncyclopedia of Behavioral MedicineNew York, NYSpringer2013227228

- Sözeri-VarmaGDepression in the elderly: clinical features and risk factorsAging Dis201436465471

- TsangRSMatherKASachdevPSReppermundSSystematic review and meta-analysis of genetic studies of late-life depressionNeurosci Biobehav Rev20177512913928137459

- AzizRSteffensDCWhat are the causes of late-life depression?Psychiatr Clin North Am201336449751624229653

- WeyererSEifflaender-GorferSKöhlerLGerman AgeCoDe Study group (German Study on Ageing, Cognition and Dementia in Primary Care Patients)Prevalence and risk factors for depression in non-demented primary care attenders aged 75 years and olderJ Affect Dis20081112–315316318372049

- FriedLPTangenCMWalstonJFrailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotypeJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2001563M146M15611253156

- SoysalPStubbsBLucatoPInflammation and frailty in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysisAgeing Res Rev2016311827592340

- ArtsMHCollardRMComijsHCRelationship between physical frailty and low grade inflammation in late life depressionJ Am Geriatr Soc20156381652165726200706

- Artaza-ArtabeISáez-LópezPSánchez-HernándezNFernández-GutierrezNMalafarinaVThe relationship between nutrition and frailty: effects of protein intake, nutritional supplementation, vitamin D and exercise on muscle metabolism in the elderly. A systematic reviewMaturitas201693899927125943

- CoppenABolander-GouailleCTreatment of depression: time to consider folic acid and vitamin B12J Psychopharmacol2005191596515671130

- OkerekeOISinghAThe role of vitamin D in the prevention of late-life depressionJ Affect Dis201619811426998791

- ColeMGDendukuriNRisk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysisAm J Psychiatry200316061147115612777274

- RichardEReitzCHonigLHLate-life depression, mild cognitive impairment, and dementiaJAMA Neurol2013703383389

- SteffensDCLate-life depression and the prodromes of dementiaJAMA Psychiatry201774767367428514459

- AlmeidaOPHankeyGJYeapBBGolledgeJFlickerLDepression as a modifiable factor to decrease the risk of dementiaTransl Psychiatry201775e111728463236

- KorczynADHalperinIDepression and dementiaJ Neurol Sci2009283113914219345960

- TaylorWDAizensteinHJAlexopoulosGSThe vascular depression hypothesis: mechanisms linking vascular disease with depressionMol Psychiatry201318996397423439482

- TiemeierHvan DijckWHofmanAWittemanJCStijnenTBretelerMMRelationship between atherosclerosis and late-life depression: the Rotterdam StudyArch Gen Psychiatry200461436937615066895

- KajiTMishimaKKitamuraSRelationship between late life depression and life stressors: large-scale cross-sectional study of a representative sample of the Japanese general populationPsychiatry Clin Neurosci201064442643420492557

- Chang-QuanHZheng-RongWYong-HongLYi-ZhouXQing-XiuLEducation and risk for late life depression: a meta-analysis of published literatureInt J Psychiatry Med201040110912420565049

- PrinceMJHarwoodRHBlizardRAThomasAMannAHSocial support deficits, loneliness and life events as risk factors for depression in old age. The Gospel Oak Project VIPsychol Med19972723233329089825

- DjernesJKPrevalence and predictors of depression in populations of elderly: a reviewActa Psychiatr Scand2006113537238716603029

- MitchellAJBirdVRizzoMMeaderNDiagnostic validity and added value of the Geriatric Depression Scale for depression in primary care: a meta-analysis of GDS 30 and GDS 15J Affect Disord20101251101719800132

- WatsonLCPignoneMPScreening accuracy for late-life depression in primary care: a systematic reviewJ Fam Pract2003521295696414653982

- ManeaLGilbodySHewittCIdentifying depression with the PHQ-2: a diagnostic meta-analysisJ Affect Disord201620338239527371907

- HaringsmaREngelsGBeekmanASpinhovenPThe criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES D) in a sample of self-referred elders with depressive symptomatologyInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200419655856315211536

- ConradssonMRosendahlELittbrandHGustafsonYOlofssonBLövheimHUsefulness of the Geriatric Depression Scale 15-item version among very old people with and without cognitive impairmentAging Ment Health201317563864523339600

- PapassotiropoulosAHeunRMaierWThe impact of dementia on the detection of depression in elderly subjects from the general populationPsychol Med1999290111312010077299

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental HNational Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance. Depression: The Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults (Updated Edition)Leicester (UK)British Psychological Society2010

- LernerDJKannelWBPatterns of coronary heart disease morbidity and mortality in the sexes: a 26-year follow-up of the Framingham populationAm Heart J198611123833903946178

- BrownieSWhy are elderly individuals at risk of nutritional deficiency?Int J Nurs Pract200612211011816529597

- KalesHCMaixnerDFMellowAMCerebrovascular disease and late-life depressionAm J Geriatr Psychiatry2005132889815703317

- IosifescuDVClementi-CravenNFraguasRCardiovascular risk factors may moderate pharmacological treatment effects in major depressive disorderPsychosom Med200567570370616204427

- PerkJDe BackerGGohlkeHEuropean guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012)Eur Heart J201233131635170122555213

- LazarouCKapsouMThe role of folic acid in prevention and treatment of depression: an overview of existing evidence and implications for practiceComplement Ther Clin Pract201016316116620621278

- DeclercqTHabrakenHvan den AmeeleHDepressie bij volwassenen: Domus MedicarichtlijnHuisarts Nu2017461315

- LeontjevasRGerritsenDLSmalbruggeMTeerenstraSVernooij-DassenMJKoopmansRTA structural multidisciplinary approach to depression management in nursing-home residents: a multicentre, stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trialLancet201338198852255226423643110

- Catalan-MatamorosDGomez-ConesaAStubbsBVancampfortDExercise improves depressive symptoms in older adults: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analysesPsychiatry Res201624420220927494042

- OrrowGKinmonthALSandersonSSuttonSEffectiveness of physical activity promotion based in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trialsBMJ2012344e138922451477

- ZanetidouSBelvederi MurriMMenchettiMSafety Efficacy of Exercise for Depression in Seniors Study GroupPhysical exercise for late-life depression: customizing an intervention for primary careJ Am Geriatr Soc201765234835527869986

- HuangAXDelucchiKDunnLBNelsonJCA systematic review and meta-analysis of psychotherapy for late-life depressionAm J Geriatr Psychiatry201523326127324856580

- SmitFEderveenACuijpersPDeegDBeekmanAOpportunities for cost-effective prevention of late-life depression: an epidemiological approachArch Gen Psychiatry200663329029616520434

- CuijpersPvan StratenASmitFPsychological treatment of late-life depression: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trialsInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200621121139114916955421

- GouldRLCoulsonMCHowardRJCognitive behavioral therapy for depression in older people: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomized controlled trialsJ Am Geriatr Soc201260101817183023003115

- KorteJBohlmeijerETCappeliezPSmitFWesterhofGJLife review therapy for older adults with moderate depressive symptomatology: a pragmatic randomized controlled trialPsychol Med20124261163117321995889

- AllanCLEbmeierKPReview of treatment for late-life depressionAdv Psychiatr Treat2013194302309

- NelsonJCDelucchiKSchneiderLSEfficacy of second generation antidepressants in late-life depression: a meta-analysis of the evidenceAm J Geriatr Psychiatry200816755856718591576

- MarkTLJoishVNHayJWSheehanDVJohnstonSSCaoZAntidepressant use in geriatric populations: the burden of side effects and interactions and their impact on adherence and costsAm J Geriatr Psychiatry201119321122121425504

- KerseNFlickerLPfaffJJFalls, depression and antidepressants in later life: a large primary care appraisalPLoS One200836e242318560599

- LamYAntidepressant use and recurrent falls in the elderlyBrown Univ Psychopharmacol Update201627823

- AlexopoulosGSKatzIRReynoldsCF3rdCarpenterDDochertyJPThe expert consensus guideline series. Pharmacotherapy of depressive disorders in older patients. Postgraduate medicine2001Spec No Pharmacotherapy186

- KokRMNolenWAHeerenTJEfficacy of treatment in older depressed patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of double-blind randomized controlled trials with antidepressantsJ Affect Disord20121412–310311522480823

- RiefWNestoriucYvon Lilienfeld-ToalADifferences in adverse effect reporting in placebo groups in SSRI and tricyclic antidepressant trials: a systematic review and meta-analysisDrug Saf200932111041105619810776

- BeachSRKostisWJCelanoCMMeta-analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-associated QTc prolongationJ Clin Psychiatry2014755e441e44924922496

- RajjiTKMulsantBHLotrichFELokkerCReynoldsCF3rdUse of antidepressants in late-life depressionDrugs Aging2008251084185318808208

- GebaraMALipseyKLKarpJFNashMCIaboniALenzeEJCause or effect? Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and falls in older adults: a systematic reviewAm J Geriatr Psychiatry201523101016102825586602

- AlexopoulosGSPharmacotherapy for late-life depressionJ Clin Psychiatry2011721e0421272511

- TaylorWDDepression in the elderlyN Engl J Med2014371131228123625251617

- Ancoli-IsraelSAyalonLDiagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders in older adultsAm J Geriatr Psychiatry20061429510316473973

- FoxCBTreadwayAKBlaszczykATSleeperRBMegestrol acetate and mirtazapine for the treatment of unplanned weight loss in the elderlyPharmacotherapy200929438339719323618

- JungYJunTKimKBahkWHyponatremia associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, mirtazapine, and venlafaxine in Korean patients with major depressive disorderInt J Clin Pharmacol Ther201149743744321726494

- van der WurffFBStekMLHoogendijkWJBeekmanATThe efficacy and safety of ECT in depressed older adults: a literature reviewInt J Geriatr Psychiatry2003181089490414533122

- DombrovskiAYMulsantBHThe evidence for electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in the treatment of severe late-life depression. ECT: the preferred treatment for severe depression in late lifeInt Psychogeriatr200719110142735 discussion 24–617166293

- KellnerCRoy-ByrnePPSolomonDUnipolar major depression in adults: indications for and efficacy of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)2015 Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/unipolar-major-depression-in-adults-indications-for-and-efficacy-of-electroconvulsive-therapy-ectAccessed March 05, 2018

- GeduldigETKellnerCHElectroconvulsive therapy in the elderly: new findings in geriatric depressionCurr Psychiatry Rep20161841626685903

- KumarSMulsantBHLiuAYBlumbergerDMDaskalakisZJRajjiTKSystematic review of cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy in late-life depressionAm J Geriatr Psychiatry201624754756527067067

- VerwijkEComijsHCKokRMSpaansHPStekMLScherderEJNeurocognitive effects after brief pulse and ultrabrief pulse unilateral electroconvulsive therapy for major depression: a reviewJ Affect Disord2012140323324322595374

- SpaansHPSienaertPBouckaertFSpeed of remission in elderly patients with depression: electroconvulsive therapy v. medicationBr J Psychiatry20152061677125323140

- van der Feltz-CornelisCMTowards integrated primary health care for depressive disorder in the Netherlands. The depression initiativeInt J Integr Care200992e8319590609

- RichardsDAHillJJGaskLClinical effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in UK primary care (CADET): cluster randomised controlled trialBMJ2013347f491323959152

- ThotaABSipeTAByardGJCommunity Preventive Services Task ForceCollaborative care to improve the management of depressive disorders: a community guide systematic review and meta-analysisAm J Prev Med201242552553822516495

- UnützerJKatonWJFanMYLong-term cost effects of collaborative care for late-life depressionAm J Manag Care20081429510018269305