Abstract

Purpose:

Northern Thailand is a tuberculosis (TB) endemic area with a high TB death rate. We aimed to establish the time of highest death risk during TB treatment, and to identify the risk factors taking place during that period of high risk.

Patients and methods:

We explored the TB surveillance data of the Chiang Rai province, Northern Thailand, retrospectively for 12 years. A total of 19,174 TB patients (including 5,009 deaths) were investigated from 1997 to 2008, and the proportion of deaths in each month of TB treatment was compared. Furthermore, multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the characteristics of patients who died in the first month of TB treatment. A total of 5,626 TB patients from 2005 to 2008 were included in this regression analysis.

Result:

The numbers of deaths in the first month of TB treatment were 38%, 39%, and 46% in the years 1997–2000, 2001–2004, and 2005–2008, respectively. The first month of TB treatment is the time of the maximum number of deaths. Moreover, advancing age, HIV infection, and being a Thai citizen were significant factors contributing to these earlier deaths in the course of TB treatment.

Conclusion:

Our findings have pointed to the specific time period and patients at higher risk for TB death. These findings would be useful for prioritizing interventions in order to diminish TB-related deaths globally. Studies based on these findings are necessary for the introduction of newer intervention strategies.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is still a worldwide deadly threat despite global and national control programs. Every year there are two million TB-related deaths globally.Citation1 The global TB mortality rate was 29/100,000 in 1990 and increased to peak at 32/100,000 in 2000 before decreasing to 27/100,000 in 2007.Citation2 After a decades-long battle against TB, the World Health Organization (WHO) has set the goal to reduce TB mortality below 15 per 100,000 by 2015.

TB mortality rate is different in developing and developed countries. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance report in 2008 showed that TB mortality in the United States was 0.2 per 100,000.Citation3 In contrast, Thailand, which was ranked 18th of the top 22 highest TB-burdened countries, had a mortality rate of 21/100,000 in 2007.Citation4 Furthermore, even with the low level of mortality, the proportion of pulmonary TB patients who died during treatment was reported to be highest in the WHO European region.Citation2,Citation5 The disease is still the cause of death for large numbers of people across the world.

In recent years, Thailand could not achieve the WHO target treatment success rate. One of the reasons for this is the high proportion of TB death on treatment: 11% in 2001 and 9% in 2007, which were the highest proportions in the WHO Southeast Asian region. These figures were very similar to the proportion of TB patients’ deaths (8%) reported by the European region, which was the highest among all WHO regions in 2007.Citation5 Chiang Rai province, the study site of the current study, is a TB and HIV endemic area. It has a higher TB case fatality rate (17.1%) than its neighboring provinces in Northern Thailand.Citation6 Previous literature has stated that living in Chiang Rai province itself is a risk factor of death among TB patients (adjusted relative risk 2.7).Citation7

TB is a chronic communicable disease that is curable. Moreover, TB death is preventable. To aid prevention, it is necessary to specify the time, place, and persons at higher risk of death. Identifying the time when most TB deaths occur during the course of treatment is necessary. Characteristics of patients who died of TB during that high-risk period should be observed to specify social and clinical risk groups of TB death.

We aimed to find out the time of highest on-treatment death along the timeline of TB treatment. Furthermore, we tried to identify the characteristics of TB patients who died during that high-risk period.

Material and methods

Data collection and source

TB surveillance data were used for the study. The study was approved by Chiang Rai Ethical Committee and Chiang Rai Provincial Health Office, Thailand. TB surveillance data covered 17 hospitals in Chiang Rai province.

Study population

The study population comprised TB patients selected based on the following criteria. These criteria were applied for both parts of the analysis.

Inclusion criteria

All TB cases treated and reported in Chiang Rai province, including new cases, relapse, treatment after failure, treatment after default, and others according to WHO criteria.

Pulmonary as well as extrapulmonary tuberculosis.

Exclusion criteria

Defaulted TB cases.

Transfer-in cases from other areas and transfer-out cases during treatment.

Patients less than 16 years of age.

The study contained two parts. In the first part of the study, TB surveillance data of the past 12 years were examined. All 5009 deaths among 19,174 TB patients from 1997 to 2008 were retrospectively studied.

Secondly, to analyze the factors associated with patients who died during the period of highest death, prospectively collected data were used. A total of 5,626 TB patients from 2005 to 2008 were included in the second part of the analysis. Populations in the first and second part of the analysis had the same criteria for inclusion and exclusion. Hypothesis-driven data collection was started in 2005 beyond the scope of routine surveillance. It was made successful because of the Thailand TB Active Surveillance Network (TB-Net). TB-Net was a collaboration of the Ministry of Public Health, Thailand, Bangkok Metropolitan Administration, the Research Institute of Tuberculosis, Japan, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in five provinces of Thailand, including Chiang Rai. This analysis used the data collected by the RIT in Chiang Rai province.

TB treatment

TB patients in Chiang Rai province were treated according to National TB Program treatment guidelines. Choice of TB treatment regimen was based on the criteria of new case, retreatment, and drug resistance regimen according to the treatment category in the WHO guidelines.Citation8

Death

Death from any cause during TB treatment was listed as on-treatment TB death according to the WHO TB treatment outcome definition.Citation8 Death during TB treatment was confirmed by using hospital records and the death registry in the online national vital status database.

Laboratory tests

Microscopic examination of sputum samples for acid-fast bacilli by Ziehl–Neelsen stain was carried out in the mycobacterial laboratory of each hospital in Chiang Rai province. Bacteriological diagnosis of tuberculosis culture was done at the mycobacterial laboratory of the Chiang Rai provincial hospital. Throughout the study period, solid culture via Ogawa medium was used. After October 2005, automated liquid culture system Bactec™ Mycobacterial Growth Indicator Tube (MGIT 960™) was used for TB culture. Drug susceptibility tests (DSTs) were carried out at the National TB Reference Laboratory, Bangkok, Thailand, by using the proportion method with a Lowenstein–Jensen medium before 2005. After 2005, identification and DSTs for isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and streptomycin were performed at the National TB Reference Laboratory using MGIT. Voluntary counseling and testing of HIV infection was offered to every TB patient. Consented cases were tested for HIV antibody.

Statistical analysis

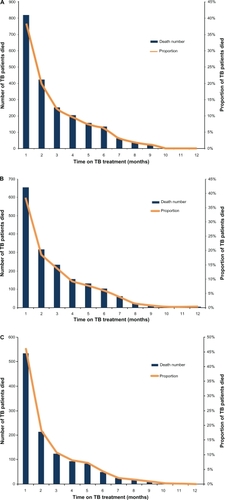

Stata Version 11 was used to analyze the data. Of 5009 total deaths from 1997 to 2008, the number and proportion of deaths in each month of TB treatment were analyzed descriptively and shown graphically for every 4-year interval for 1997–2000, 2001–2004, and 2005–2008 (–).

Figure 1 A) Deaths of TB patients in each month of TB treatment in Chiang Rai, Thailand (1997–2000). B) Deaths of TB patients in each month of TB treatment in Chiang Rai, Thailand (2001–2004). C) Deaths of TB patients in each month of TB treatment in Chiang Rai, Thailand (2005–2008).

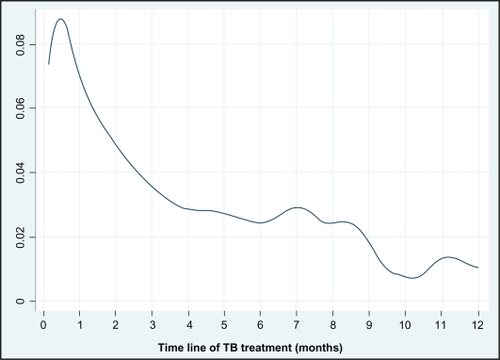

A total of 5,009 deaths occurred among 19,174 reported TB patients within 12 years. The events of death were analyzed against the timeline of TB treatment using smooth hazard risk estimation. The probability of death in the time-line of TB treatment was extrapolated by Kernel smoothed hazard rates estimation curve ().

Figure 2 Smoothed hazard estimation of on-treatment TB deaths in Chiang Rai, Thailand (1997–2008). Y-axis is showing the probability of on-treatment TB death. X-aixs is showing the timeline of TB treatment.

Backward multilogistic regression analysis was performed to identify factors associated with the TB patients who died within the first month. Factors that contributed to 534 TB patients’ deaths in the first month of treatment were investigated and compared with 5,092 survivors. Multiple logistic regression was restricted to variables with a P value less than 0.1 in bivariate analysis. Gender, age, race, marital status, education, occupation, BCG scar, patient type based on treatment regimen, and HIV status were included in multilogistic regression. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant, with a 95 percent confidence interval (CI) to determine adjusted odds ratio (aOR).

Results

First part of the analysis

Our observation showed that the largest number of TB patients died in the first month of TB treatment. Death rates in the first month were 38% of all TB deaths in 1997–2000, 39% of all TB death in 2001–2004, and 46% of all TB death in 2005–2008 (, , and ). The largest proportion of TB patients died in the first month of TB treatment in a constant pattern for 12 years.

The result of time-event analysis by Kernel smoothed hazard rates estimation curve revealed higher probability of TB death in the first month (). The trend of TB deaths can be seen to decline over the timeline of TB treatment.

Second part of the analysis

Analysis of factors associated with TB deaths in the first month included 5626 TB patients. The basic characteristics of patients are shown in . The proportion of male patients was higher than female patients. More than 85% of the patients were Thai, and more than a third were HIV infected.

Table 1 Characteristics of TB patients included in the analysis

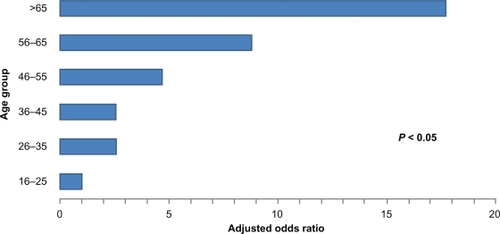

The results of bivariate and multivariate analysis are shown in . Age group, HIV status, and being a Thai citizen were significant risk factors associated with death in the first month of TB treatment after adjustment by multivariate analysis. The risk of death in the first month of TB treatment was found to be higher with advancing age ().

Figure 3 Risk of TB death during the first month of TB treatment in different age groups in Chiang Rai, Thailand (2005–2008).

Table 2 Factors associated with TB patients who died in the first month of TB treatment in Chiang Rai, Thailand (2005–2008)

Adjusted odds ratio were: aOR 17.1, CI 8.54–36.73 for age above 65 years; aOR 8.76, CI 4.15–18.45 in age 56–65 years group; aOR 4.60, CI 2.22–9.54 in age 46–55 years group; aOR 2.53, CI 1.23–5.21 in age 36–45 years group; and aOR 2.57, CI 1.26–5.24 in age 26–35 years group compared with the age 16–25 years group.

HIV-positive patients are more likely to die in the first month of TB treatment (aOR 3.24, CI 2.46–4.26) than HIV-negative patients. Thai citizens have a higher risk of TB death in the first month of treatment (aOR 2.26, CI 1.28–4.00) than Myanmar and Lao migrants. Married patients have less risk for TB death in the first month (aOR 0.61, CI 0.45–0.83) than single patients.

Discussion

Time of highest on-treatment TB death

Death caused by TB is preventable. Management and care can be modified at the time of highest risk for death. Many researches and reports have discussed TB mortality and factors associated with TB mortality. Usually, all TB deaths are summarized as one of the treatment outcomes at the end of TB treatment. There is still a gap in the evidence needed to know the time of highest mortality.

Our observation of surveillance data over 12 years revealed that the highest proportion of TB deaths happened during the first month of TB treatment. The finding was persistent for more than a decade (–). The number of overall deaths became lower during the later 4 years 2005–2008. During 1997–2000, there was a lack of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for TB–HIV co-infected patients in Chiang Rai. After 2000, ART was provided by a national program, and access to ART was expanded with time. This may have led to an overall decline in the death rate in later years of observation. Nevertheless, the proportion of deaths was still the highest in the first month of TB treatment (, , and ).

Harries et al identified in 1997 that 40% of TB deaths occurred in the first month of TB treatment in Malawi.Citation9 It was an interesting report, with particular observation of the time of highest death during TB treatment. The percentage of death in the first month was very similar to our observation. The finding was based on 1-year data from the TB registry in 1997 from 38 hospitals in Malawi. It would be more informative to see the trend of TB deaths in subsequent years, because there were many changes, such as HIV prevalence, TB control activity, and policy. In our report, the proportion of TB deaths in the course of treatment can be seen serially for 12 years.

The same author in 2001 reported 40%–45% of all TB deaths in the first month of TB treatment regardless of daily or intermittent regimens in Malawi.Citation10 All these studies were at the same site, Malawi, which is a TB and HIV endemic area in Africa. Sub-Saharan Africa has a very high HIV prevalence that considerably fuels the TB death rates. However, other WHO regions, such as Southeast Asia and Europe, currently have a different HIV prevalence and TB epidemiology from those of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Our observation in Northern Thailand has identified the first month of TB treatment as the time of highest risk for TB death. The same pattern has continued consecutively for more than a decade. Therefore, it would be practical to launch interventions focusing on the first month of TB treatment in order to cut mortality. Our finding is expected to be applicable in many countries with similar TB epidemiology and problems globally.

Factors related to death in first month of TB treatment

Factors particularly associated with TB death in the first month of treatment were investigated to identify at-risk groups of patients. Clinical, laboratory, and sociodemographic factors were analyzed. We found that advancing age, HIV infection, and being Thai were strongly associated with death in the first month of TB treatment.

Previously, studies across the world have shown the factors associated with TB mortality. Mostly, factors associated with treatment outcome death were reported. A few studies pointed out the risk factors for early death. Even before the HIV pandemic, early TB death and an association with older patients were stated in England and Wales.Citation11 A low body mass index less than 17.0 kg/m2 was also revealed as a risk factor for early mortality.Citation12 A later study in Africa reported a higher death rate in HIV-positive TB patients.Citation13

Our result has shown the higher risk of early TB death with advancing age. The death rate in the first month specified by age groups increased with advancing age (). AOR increased progressively with advancing age (). TB patients aged above 65 years were found to have the highest risk compared with other adult age groups (aOR 17.71, 95% CI 8.54–36.73).

Previous studies in various regions of the world reported high risk for elderly TB patients, but the risk was not specified for death in the first month.Citation7,Citation11,Citation14–Citation19 Recently, analysis of TB surveillance data from 15 European Union (EU) countries during 2002–2004 reported that advancing age and resistance to isoniazid and rifampicin were the strongest risks of TB death.Citation19 Therefore, our finding agreed with existing evidence for those at high-risk of TB death. Moreover, we specified the most likely time of death for these high-risk patients. However, the WHO definition of TB death covered death from any cause during TB treatment. Elderly TB patients might have comorbid diseases. Thus, it is difficult to claim TB as the sole contributor of death.

Currently, TB and HIV are two of the deadliest chronic infections globally.Citation20 In our study cohort from 2005–2008, 31% of all the TB patients were HIV positive. Among the deaths of patients during the first month, 35.6% were HIV positive (). HIV-infected TB patients have significant risk for death in the first month of TB treatment. The aOR was 3.24 (2.46–4.26). Unidentified status of HIV infection was also a risk factor for earlier TB death.

Previous studies have stated that HIV infection is an important risk factor for TB mortality.Citation21–Citation23 Early deaths of TB–HIV co-infected patients were more likely caused by TB rather than other opportunistic infections.Citation21 CD4 cell depletion is a possible explanation for the higher death rates in HIV-positive TB patients. Consequently, timely ART would be an important factor. Moreover, adverse effects are common because of interaction between antiretroviral drugs and anti-TB drugs.

Historically, TB was said to be a disease of poor people. The risk of TB death and its time of occurrence could be related to socioeconomic factors. However, in our analysis, occupation and educational status of the patients were not significant after adjustment with a multilogistic regression model. Final analysis showed that being a Thai citizen is a significant risk factor. A similar observation was reported in a European study and was explained as the healthy migrant effect.Citation19 Bacteriological factors related to causal organism like culture positivity, drug resistance, and multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) were not significant factors in the current study. However, previous studies in Thailand and Europe reported that MDR-TB was a significant risk for overall TB death.Citation7,Citation19 The different finding could be due to a different time point of analysis and low level of MDR-TB prevalence in Chiang Rai.

More complete clinical data should be analyzed to identify risk groups who could die earlier. Recently, a study of 311 hospitalized TB patients in Brazil reported high mortality rates among hospitalized TB patients in a highly HIV prevalent setting. Respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, smear negative sputum, and consolidation in chest X-ray are identified as predictors of in-hospital death.Citation24 It was a limitation of our study that we could not explore much about the factors related to anti-TB drugs, which were in fact a constant exposure in the study cohort. Most of our study cohort (more than 85%) comprised new cases treated by a WHO category I regimenCitation8 (). Daphne and colleagues have reported that the occurrence of serious side effects of anti-TB drugs were more common in patients aged over 65 years and in HIV-positive patients.Citation25 In the past, one of the inclusion criteria of clinical trials was patients’ age to be between 15 and 65 years.Citation26 Therefore, it is hard to know about adverse events in TB patients aged above 65 years. Further studies of decades-old TB regimens in elderly patients would be necessary.

The time of highest TB deaths was found to be the earlier period in TB treatment. Delayed diagnosis and late presentation may be associated with early TB death. However, a study in Vietnam reported that diagnostic delay was not associated with TB treatment outcome mortality.Citation18 Prospective studies beyond the scope of surveillance, based on contemporary evidence, should be assembled in future.

Suggestions and proposed strategies

Our analysis showed that elderly patients and HIV co-infected patients were the people at higher risk for early TB death. Elderly patients can have other allied illnesses, such as malignancy, other respiratory infections, and underlying liver diseases, which may lead to earlier TB death. A hospital-based prospective study focusing on the elderly and further analysis of more complete information on cause of death is necessary. A careful start to the administration of anti-TB drugs with a body weight-based adjusted dose, complete baseline clinical and laboratory investigations, and more frequent follow-ups are necessary. A TB hospital providing meticulous care of high-risk patients at the initiation of TB treatment in such an endemic area may be fruitful to save these risk groups.

To prevent early TB death in TB–HIV co-infected patients, ART coverage and access to ART is crucial in all settings, as the decline of overall death rate in later years of our observation has shown (). During the 12 years of the current study period, up to 2008, Thailand national guidelines recommended deferring ART in TB-HIV co-infection until 2 months after initiation of TB treatment in cases with CD4 count more than 200 cells/ul.Citation27,Citation28 New national guidelines for Thailand in 2010 changed the recommendation to start ART earlier but still, to defer ART if CD4 count is above 350 cells/ul.Citation29 Current international guidelines recommend starting ART in HIV infected persons with active TB disease irrespective of their CD4 count.Citation30,Citation31. This strategy would help to reduce the early TB deaths in TB-HIV patients.

In conclusion, current study findings are useful clues for launching realistic prevention strategies against TB deaths in many countries. Across the course of TB treatment, the first month sees the highest number of TB deaths. During that first month, elderly patients and HIV-infected patients are at significantly high risk of death. It is expected that prioritizing interventions focused on high-risk times and high-risk patients will diminish mortality related to TB globally.

Acknowledgements

All the staffs of the TB clinics at 17 hospitals in Chiang Rai province and the staffs of TB/HIV Research Foundation are acknowledged for their help and support. Thailand TB Active Surveillance Network (TB-Net) is acknowledged for collaboration of the TB surveillance system from 2005 to 2008. Thaworn Lorga, Boromrajonani College of Nursing, Lampang, Thailand is acknowledged for his important suggestions

Disclosure

No conflicts of interest were declared in relation to this paper.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionFact sheet: A global perspective on tuberculosis2009 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/tb/events/WorldTBDay/resources_global.htm. Accessed Dec 18, 2010.

- [WHO] World Health OrganizationWHO report 2009: Global tuberculosis control Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2009/key_points/en/index.html. Accessed Dec 18, 2010.

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionReported tuberculosis in the United States2008 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/tb/statistics/reports/2008/default.htm. Accessed Dec 18, 2010.

- [WHO] World Health OrganizationTB in South-East Asia: Epidemiology of TB in the Region Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/en/Section10/Section2097/Section2100_10639.htm.htm. Accessed Dec 18, 2010.

- [WHO] World Health OrganizationTB data: Data collected from TB control programmes and estimates generated by WHO, treatment outcomes, new smear-positive cases1995–2007 Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/country/data/download/en/index.html. Dec 18, 2010.

- MoolphateSTB HIV situation in Chaing Rai provinceReport presented at: The 14th TB HIV Annual Meeting2010 January 13Chiang Rai, Thailand Chiang Rai

- AmnuaiphonWAnuwatnonthakateANuyongphakPFactors associated with death among HIV-uninfected TB patients in Thailand, 2004–2006Trop Med Int Health2009201420111338204619735372

- [WHO] World Health OrganizationTreatment of tuberculosis: guidelines for national programmes4th edWHO2009420

- HarriesADHargreavesNJGausiFKwanjanaJHSalaniponiFMHigh early death rate in tuberculosis patients in MalawiInt J Tuberc Lung Dis20015111000100511716335

- HarriesADGausiFKKwanjanaJHNyirendaTESalaniponiFMIs oral intermittent initial phase anti-tuberculosis treatment associated with higher mortality in high HIV-prevalent areas in sub-Saharan Africa?Int J Tuberc Lung Dis20015548348511336281

- HumphriesMJByfieldSPDarbyshireJHDeaths occurring in newly notified patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in England and WalesBr J Dis Chest1984781491586722018

- ZachariahRSpielmannMPHarriesADSalaniponiFMModerate to severe malnutrition in patients with tuberculosis is a risk factor associated with early deathTrans R Soc Trop Med Hyg200296329129412174782

- Kang’ombeCHarriesADBandaHHigh mortality rates in tuberculosis patients in Zomba Hospital, Malawi, during 32 months of follow-upTrans R Soc Trop Med Hyg200094330530910975007

- ShenXDeriemerKYuanZDeaths among tuberculosis cases in Shanghai, China: who is at risk?BMC Infect Dis200999519531267

- FacanhaMCEvolution of tuberculosis-related mortality in Fortaleza, Brazil from 1980 to 2001J Bras Pneumol200632655355817435906

- Najera-OrtizJSanchez-PerezHOchoa-DiazHArana-CedenoMLezamaMSMateoMMDemographic, health services and socioeconomic factors associated with pulmonary tuberculosis mortality in Los Altos Region of Chiapas, MexicoInt J Epidemiol200837478679518511492

- KolappanCSubramaniRKumaraswamiVSanthaTNarayananPRExcess mortality and risk factors for mortality among a cohort of TB patients from rural south IndiaInt J Tuberc Lung Dis2008121818618173882

- VreeMHuongNDuongBHigh mortality during tuberculosis treatment does not indicate long diagnostic delays in Vietnam: a cohort studyBMC Public Health20077121017705838

- LefebvreNFalzonDRisk factors for death among tuberculosis cases: analysis of European surveillance dataEur Resp J200831612561260

- HarringtonMFrom HIV to tuberculosis and back again: a tale of activism in 2 pandemicsClin Infect Dis201050S3S260S26620397957

- ChurchyardGJKleinschmidtICorbettELMurrayJSmitJde CockKMFactors associated with an increased case-fatality rate in HIV-infected and non-infected South African gold miners with pulmonary tuberculosisInt J Tuberc Lung Dis20004870571210949321

- MugusiFMehtaSVillamorEFactors associated with mortality in HIV-infected and uninfected patients with pulmonary tuberculosisBMC Public Health20099140919909501

- MurrayJSonnenbergPShearerSCGodfrey-FaussettPHuman immunodeficiency virus and the outcome of treatment for new and recurrent pulmonary tuberculosis in African patientsAm J Respir Crit Care Med1999159373374010051244

- SilvaDRMenegottoDMSchulzLFGazzanaMBDalcin PdeTFactors associated with mortality in hospitalized patients with newly diagnosed tuberculosisLung20101881334120131479

- YeeDValiquetteCPelletierMParisienIRocherIMenziesDIncidence of serious side effects from first-line antituberculosis drugs among patients treated for active tuberculosisAm J Respir Crit Care Med2003167111472147712569078

- JindaniANunnAJEnarsonDATwo 8-month regimens of chemotherapy for treatment of newly diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis: international multicentre randomised trialLancet200436494411244125115464185

- SungkanuparphSAnekthananonTHiransuthikulNGuidelines for antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infected adults and adolescents: the recommendations of the Thai AIDS Society (TAS) 2008J Med Assoc Thai200891121925193519133532

- Department of Disease Control MoPHThailand National Antiretroviral Treatment Guideline (2006/2007)

- SungkanuparphaSTechasathitWTUtaipibooncCThai national guidelines for antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infected adults and adolescents 2010Asian Biomed201044515528

- [WHO] World Health OrganizationAntiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/adult2010/en/index.html. Accessed Dec 18, 2010.

- ThompsonMAAbergJACahnPAntiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2010 Recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA PanelJAMA2010304332133320639566