Abstract

Background

A do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order is reportedly associated with a decrease in performance measures, but it should not be applied to noncardiopulmonary resuscitation procedures. Good performance measures are associated with improvement in heart failure outcomes.

Aim

To analyze the influence of DNR order on performance measures of heart failure at our hospital, where lectures on DNR order are held every 3 months.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Methods

The medical report of patients with acute heart failure who were admitted between April 2013 and March 2015 were retrospectively analyzed. We collected demographic data, information on the presence or absence of DNR order within 24 hours of admission, and inhospital mortality. Performance measures of heart failure, including assessment of cardiac function and discharge prescription of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker and beta-blocker for left ventricular systolic dysfunction and anticoagulant for atrial fibrillation, were collected and compared between groups with and without DNR orders.

Results

In 394 total patients and 183 patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction, 114 (30%) and 44 (24%) patients, respectively, had a DNR order. Patients with a DNR order had higher inhospital mortality. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of the four quality measures (left ventricular function assessment, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, beta-blocker, and anticoagulant).

Conclusion

DNR orders did not affect performance measures, but they were associated with higher inhospital mortality among acute heart failure patients.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a major and inevitable public health issue worldwide. Between 2004 and 2014, although death rates due to cardiovascular disease (CVD) declined by 25.3%, and the actual number of CVD deaths decreased by 6.7%, CVD remains one of the most common leading causes of death.Citation1 In Japan, the prevalence of HF is increasing, especially in elderly populations, and one report estimated that the number of Japanese outpatients with left ventricular dysfunction would increase gradually as patients age, reaching 1.3 million by 2030.Citation2 Performance measures in hospitalized HF patients have been developed to improve their care.Citation3 Adhering to these measures on routine daily care was found to contribute to a decrease in mortality in acute heart failure (AHF) patients.Citation4

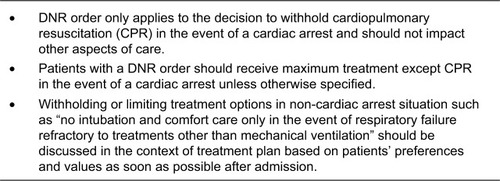

Documentation of a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order is a part of end-of-life care intended to allow patients to forgo cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in the event of cardiac arrest.Citation5,Citation6 They are only applied to cases of cardiac arrest, and they cannot be applied to any situation other than cardiac arrest.Citation5,Citation6 In the USA, a DNR order was associated with a decrease in performance measures and higher mortality in AHF patients.Citation7 HF is a progressive disease, and its prognosis is not good. The American Heart Association (AHA) recommended that physicians should start end-of-life care discussion for future event, including resuscitation preference during the earlier stage of the illness.Citation8 However, a DNR order poses a risk of worse prognosis due to worsening quality of HF care.Citation7

A DNR order was reported to affect decision making in non-CPR procedures not only in the USA but also in Japan.Citation9,Citation10 Therefore, it is important to educate physicians with the definition of a DNR order and its proper implementation to prevent its misuse. In our hospital, we started lectures on DNR order for physicians in 2013. This retrospective study evaluated the influence of DNR status on the quality of inhospital clinical performance in acute AHF patients.

Methods

Subjects

This retrospective, single-center, cohort study included patients who were admitted to our acute care teaching hospital with a primary diagnosis of AHF between April 2013 and March 2015. The medical charts of adult patients (>18 years) with primary diagnosis of AHF on admission were reviewed. We confirmed the diagnosis of HF based on the Framingham criteria.Citation11

Setting

Our hospital is an acute teaching hospital, where AHF patients are under the care of a general internal medicine (GIM) team, which consists of two or three residents and one hospitalist attending physician. Cardiologists are always available as consultant. GIM residents rotate every 3 months and spend 6 months in internal medicine wards in our hospital per year, which meets the requirement of GIM residency training in Japan. Since 2013, we give a lecture on the definition of DNR order and its proper implementation at the beginning of each 3 months’ rotation of medical wards (). Therefore, residents and hospitalist attending physicians have a chance to participate in the lecture two and four times a year, respectively.

Data collection

Patients’ demographic data, DNR status within 24 hours after admission, and laboratory data on admission as well as echocardiography data during the hospitalization and inhospital mortality were collected. According to AHA guidelines, performance measures of inpatient HF include five items: 1) evaluation of left ventricular systolic function, 2) angiotensin- converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) for left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD), 3) anticoagulant at discharge for HF patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), 4) discharge instructions, and 5) adult smoking cessation advice/counseling.Citation3 We chose the cardiac function assessment, ACEi, or ARB use for LVSD and anticoagulant for AF because discharge instruction and smoking cessation advice are often performed but not documented in hospital charts; therefore, those data may be imprecise. Because beta- blocker is also an important treatment for LVSD to improve mortality and quality of life, it was also added as a quality measure. LVSD is defined as ejection fraction of 40% or lower.Citation3 Patients who were not prescribed ACEi, ARB, beta-blocker, or anticoagulant for documented reasons were excluded: ACEi or ARB for hypotension, renal insufficiency, or hyperkalemia; beta-blocker for hypotension, bradycardia, asthma, or inotrope use; anticoagulant for bleeding event or poor prognosis. We also excluded patients who died during hospitalization.

Informed consent and institutional review board approval

This study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Tokyo Bay Urayasu Ichikawa Medical Center. Because of the anonymous nature of the data, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean±SD, and discrete variables were summarized as percentages. Continuous variables and dichotomous variables were analyzed and compared using t-test and chi-squared test, respectively. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

The total number of patients was 394, of whom 183 had LVSD. The mean age was 73±14 years, and 56% were men. The characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes based on the presence of DNR orders for all patients and for patients with LVSD are presented in and , respectively. Approximately 30% of all patients and 24% of LVSD patients had DNR orders on admission ( and ). Patients with DNR orders tended to be older and were more likely to be women. They were more likely to have incomplete decision-making capacity, to be ADL-dependent, and to have dementia than patients without DNR orders ( and ). Meanwhile, there were no significant differences between the presence and the absence of DNR orders in terms of other comorbidities, including kidney dysfunction and lung disease. Inhospital mortality was 6.1% and it was significantly higher in the DNR group than the non-DNR group.

Quality measures

Assessment of cardiac function by echocardiography

In terms of rate of assessment of cardiac function by echocardiography, almost all patients (99%) underwent echocardiography, and there was no statistically significant difference between the DNR and the non-DNR groups ().

Table 1 Patient characteristics according to DNR status

Table 2 Characteristics of HF patients with reduced ejection fraction according to DNR status

Table 3 DNR order and quality measures among acute heart failure inpatients

Prescription rate of ACEi or ARB and beta-blocker on discharge for treatment of HF with reduced ejection fraction

Of 394 patients, 183 (46%) had LVSD, of whom 13 (7%) died during hospitalization. In 13 patients (7.6%) of the 170 survivors, beta-blocker was considered but was not prescribed because of contraindications, such as hypotension, bradycardia, asthma, or inotrope use. In the remaining 122 DNR and 35 non-DNR patients, 148 (94%) were prescribed a beta-blocker on discharge. There was no statistically significant difference between the DNR and non-DNR groups ().

In 23 patients, ACEi and ARB were considered but were not prescribed because of contraindications such as hypotension, renal insufficiency, or hyperkalemia. In the remaining 29 DNR and 118 non-DNR patients, 137 (93%) were on ACEi or ARB on discharge. There was no statistically significant difference between the DNR and non-DNR groups.

Prescription rate of anticoagulant for AF

Of 394 patients, 111 (28%) had AF, of whom 8 (7%) died. Anticoagulant use was discussed but was not prescribed in 11 patients because of bleeding event or poor prognosis. Among the remaining 91 patients, 89 (97%) were on anticoagulant on discharge. There was no statistically significant difference between the DNR and non-DNR groups ().

Discussion

This study demonstrated that patients with DNR order were more likely to be elderly, have dementia, and ADL- dependent. Their decision-making capacity was more likely to be incomplete. The mortality is higher in patients with DNR orders than in those without DNR orders. This study demonstrated that DNR orders did not affect quality measures of HF in our hospital, where lectures on proper implementation of DNR orders are made regularly. This study was not designed to show similarity or noninferiority of DNR order on the quality measures of inpatient HF care. Considering the 95% CI of relative risk of DNR order (vs non-DNR order) on each quality measure (), we can infer that those were similar between the two groups. This is the first report to suggest that DNR order does not affect quality measures of inpatient HF care under circumstances shown in .

DNR orders are intended to allow patients to forgo CPR in the event of cardiac arrest and cannot be applied to any situation other than cardiac arrest.Citation6 The American Medical Association has published guidelines stating that a DNR order should not influence other therapeutic interventions that may be appropriate.Citation6 Indeed, in the USA, patients with DNR orders who were admitted for AHF were less likely to undergo assessment of their left ventricular function, receive treatment with ACEi or ARB, or undergo counseling about lifestyle modifications.Citation7 Recently, the Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine set the guideline for definition of DNR orders, which emphasizes that a DNR order must not be applied to procedures other than CPR and that indication for non-CPR procedures should be discussed with DNR patients as well.Citation12 However, the interpretation of a DNR order reportedly differs and can affect the decision making for procedures other than CPR in Japan.Citation10 Still, the DNR order carries the risk of withholding or withdrawing non-CPR procedures in Japan. Our hospital program provides internal medicine residents and physicians with lectures of DNR orders every 3 months, in which they learn the definition of DNR order and that in the presence of DNR orders, the indication for other procedures should be discussed with patients and their families in cases of advanced stage of illness. The DNR order did not affect quality measures of HF in this circumstance. The adequate method of education and frequency of DNR lectures remains to be investigated.

In addition to the AHA performance measures of inpatient HF,Citation3 another quality measure of treatment for outpatients with LVSD is beta-blocker. Recent studies suggest that beta-blockers can be safely and effectively initiated in HF patients before hospital discharge and can lead to improved clinical outcomes. The Initiation Management Predischarge Process for Assessment of Carvedilol Therapy for Heart Failure trial demonstrated that predischarge initiation of carvedilol was associated with a higher rate of beta-blocker use after hospital discharge, with no increase in hospital length of stay.Citation13,Citation14 Initiating beta-blocker in HF patients with reduced ejection fraction before discharge is important. In our study, the DNR order did not affect beta-blocker use in LVSD patients.

In this study, 7% and 6% of patients did not receive ACEi/ARB or beta-blocker, respectively. This is problematic because in patients with reduced ejection fraction, not taking these medicines was reportedly associated with increased mortality and morbidities.Citation15,Citation16 Improvement of this quality measure is mandatory to improve outcome. Various registry-based performance improvement interventions, including guideline-based clinical decision support tool kits, educational materials, benchmarked quality-of-care reports, and structured educational and collaborative opportunities, provided standardized encounter forms, checklists, pocket cards, chart stickers, patient education, and other materials for the improvement of care.Citation4 Participation in registries was associated with improvement of HF performance measures and clinical outcomes.Citation17–Citation20 In the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry, participating hospitals received quarterly benchmarked data reports on characteristics, treatments, quality measures, and clinical outcomes. During all 12 quarters from 2002 to 2004, quality measures improved significantly, inhospital inotrope use decreased, discharge instruction increased, and use of beta-blocker increased, which was associated with outcome improvement such as mortality and length of hospital stay.Citation18 Hence, we need to consider incorporating these interventions to further improve quality of care. Education on quality measures has been reported to be important for the improvement of quality of care.Citation21,Citation22 In 2009, a mandatory national accreditation program for hospitals was introduced in Denmark, with the aim of providing a framework for quality improvement for all public hospitals.Citation23 The accreditation process improved patient care in cases of stroke, HF, ulcer, diabetes, breast cancer, and lung cancer.Citation23

Education of quality measures as well as a nationwide accreditation system needs to be considered to improve quality of HF care in Japan. In terms of palliative care for patients with advanced stages of illness, a holistic approach should be adopted, including end-of-life discussion, coordination of care, assessment and treatment of symptoms, and psychological, spiritual, and bereavement support.Citation24 End-of-life discussion includes resuscitation preferences.Citation8 ACEi and beta-blocker had been shown to improve not only mortality but also quality of life and symptoms.Citation25 Therefore, even if a DNR is ordered for patients with advanced-stage HF after end-of- life discussion, ACEi and beta-blocker should be continued for symptom management as long as adverse events do not occur.

The prognosis of patients hospitalized because of AHF is not good. Our study showed that inhospital mortality was 6.1%, which was consistent with a previous report.Citation26 It has been reported that DNR discussion occurred less frequently for patients with a noncancer primary diagnosis, including HF, compared with cancer patients.Citation27,Citation28 In cases of chronic HF, patients’ health status declines slowly with occasional acute exacerbation, from which they often recover.Citation29,Citation30 By contrast, patients in the advanced stage of cancer have a more predictable progressive downward trajectory with clear prognosis.Citation29,Citation31 Therefore, it is more challenging to estimate the prognosis of chronic HF than that of cancer.Citation29 It was reported that physicians often avoided end-of-life discussion with patients with HF for fear of causing alarm and destroying hope.Citation32 Thus, end-of-life discussion is often deferred until more emergent and less favorable occasions. Consequently, these patients often have little idea of their prognosis and may have unrealistically optimistic expectations.Citation33,Citation34 Although HF has a poorer prognosis than many cancers, patients with HF establish DNR orders later in the disease course and receive more life-sustaining treatments, including CPR, than cancer patients.Citation35 As patients approach death, physicians must consider treatments to improve the quality of dying and death, focusing on palliative care, quality of life, and patient and family satisfaction rather than prolonging life.Citation36,Citation37 End-of-life discussion was associated with a decrease in unnecessary invasive procedures, including central venous catheter placement, intubation with mechanical ventilation, CPR, and increase of opioid use during the advanced stage of illnesses, including HF.Citation27 Physicians should not delay the initiation of end-of-life discussions with patients with HF to provide better quality of end of life.

In Japan, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare established a guideline for the decision-making process for end-of-life care in 2007, which was updated in 2018.Citation38 The guideline stresses the importance of not only the patient’s medical condition but also their values and preferences in the decision-making process. It also defined end of life as 2–3 months for patients with cancer and a few months to years for patients with stroke or other chronic progressive illness.Citation38 The revised guideline in 2018 incorporated the importance of advance care planning for the first time.Citation38 In our study, DNR was ordered among 28% of patients, whereas 66% of them did not have complete decision-making capacity, requiring discussion with surrogates. Therefore, physicians should start advance care planning in the early phase of the illness and before losing the decision-making capacity.

The present study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective single-center study with a relatively small population. Thus, further multiple-center studies are needed to prove the role of education on DNR system in maintaining good quality measures on HF care in Japan. Second, we did not have data on quality measures before starting the DNR lectures; therefore, we cannot make a definitive conclusion that regular lectures on DNR can prevent the misuse of DNR order for HF treatment. However, in Japan, the DNR order reportedly affects non-CPR procedure,Citation10 and we believe the lectures played an important role in its proper implementation for HF treatment. Third, although the adequate frequency of lectures on DNR order remains to be investigated, the frequency we use in our hospital, every 3 months, is feasible for other hospitals. Fourth, our study was not designed to show similarity or noninferiority with DNR order in comparison with the no-DNR order. However, based on a clinical point of view, the 95% CI of the relative risk of each quality measure showed similarity or noninferiority, but further larger studies are necessary to confirm this.

Conclusion

DNR orders possibly did not influence performance measures for HF in circumstances where DNR lectures are held every 3 months.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work

References

- BenjaminEJBlahaMJChiuveSEHeart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart AssociationCirculation201713510e146e60328122885

- KonishiMIshidaJSpringerJHeart failure epidemiology and novel treatments in Japan: facts and numbersESC Heart Fail20163314515127840692

- BonowROBennettSCaseyDEACC/AHA Clinical Performance Measures for Adults with Chronic Heart Failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures (Writing Committee to Develop Heart Failure Clinical Performance Measures): endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of AmericaCirculation2005112121853188716160201

- FonarowGCImproving quality of care and outcomes for heart failure. Role of registriesCirc J20117581783179021727753

- LoertscherLReedDABannonMPMuellerPSCardiopulmonary resuscitation and do-not-resuscitate orders: a guide for cliniciansAm J Med201012314920102982

- Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, American Medical AssociationGuidelines for the appropriate use of do-not-resuscitate ordersJAMA1991265186818712005737

- ChenJLSosnovJLessardDGoldbergRJImpact of do-not-resuscitation orders on quality of care performance measures in patients hospitalized with acute heart failureAm Heart J20081561788418585500

- AllenLAStevensonLWGradyKLA scientific statement from the American Heart Association: decision making in advanced heart failureCirculation20121251928195222392529

- BeachMCMorrisonRSThe effect of do-not-resuscitate orders on physician decision-makingJ Am Geriatr Soc200250122057206112473020

- HiraokaEHommaYNorisueYWhat is the true definition of a “Do-Not-Resuscitate” order? A Japanese perspectiveInt J Gen Med2016921322027418851

- MckeePACastelliWPMcNamaraPMKannelWBThe natural history of congestive heart failure: the Framingham studyN Engl J Med197128526144114465122894

- Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine [webpage on the Internet]Guideline of DNR order in 2016 Available from: http://www.jsicm.org/publication/kankoku_dnar.htmlAccessed January 8, 2018

- FonarowGCAbrahamWTAlbertNMCarvedilol use at discharge in patients hospitalized for heart failure is associated with improved survival: an analysis from Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF)Am Heart J2007153182.e1e1117174643

- FonarowGCGheorghiadeMAbrahamWTImportance of in-hospital initiation of evidence-based medical therapies for heart failure-a reviewAm J Cardiol20049491155116015518610

- FonarowGCAbrahamWTAlbertNMAssociation between performance measures and clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized with heart failureJAMA20072971617017200476

- MasoudiFARathoreSSWangYNational patterns of use and effectiveness of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in older patients with heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunctionCirculation2004110672473115289383

- FonarowGCAbrahamWTAlbertNMInfluence of a performance-improvement initiative on quality of care for patients hospitalized with heart failure: results of the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF)Arch Intern Med2007167141493150217646603

- FonarowGCHeywoodJTHeidenreichPALopatinMYancyCWADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee and InvestigatorsTemporal trends in clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcomes for heart failure hospitalizations, 2002 to 2004: findings from Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE)Am Heart J200715361021102817540205

- HeidenreichPALewisWRLabreshKASchwammLHFonarowGCHospital performance recognition with the Get With The Guidelines Program and mortality for acute myocardial infarction and heart failureAm Heart J2009158454655319781413

- FonarowGCAlbertNMCurtisABImproving evidence-based care for heart failure in outpatient cardiology practices: primary results of the Registry to Improve the Use of Evidence-Based Heart Failure Therapies in the Outpatient Setting (IMPROVE HF)Circulation2010122658559620660805

- WongBMLevinsonWShojaniaKGQuality improvement in medical education: current state and future directionsMed Educ201246110711922150202

- KimCSLukelaMPParekhVITeaching internal medicine residents quality improvement and patient safety: a lean thinking approachAm J Med Qual201025321121720357082

- BoghSBFalstie-JensenAMHollnagelEHolstRBraithwaiteJJohnsenSPImprovement in quality of hospital care during accreditation: a nationwide stepped-wedge studyInt J Qual Health Care201628671572027578631

- MorrisonRSMeierDECarePClinical practice. Palliative careN Engl J Med2004350252582259015201415

- GoodlinSJPalliative care in congestive heart failureJ Am Coll Cardiol200954538639619628112

- LeeDSAustinPCRouleauJLLiuPPNaimarkDTuJVPredicting mortality among patients hospitalized for heart failure: derivation and validation of a clinical modelJAMA2003290192581258714625335

- SasakiAHiraokaEHommaYAssociation of code status discussion with invasive procedures among advanced-stage cancer and noncancer patientsInt J Gen Med20171020721428769583

- AuerbachADKatzRPantilatSZFactors associated with discussion of care plans and code status at the time of hospital admission: results from the Multicenter Hospitalist StudyJ Hosp Med20083643744519084893

- MurraySAKendallMBoydKSheikhAIllness trajectories and palliative careBMJ200533074981007101115860828

- AllenLAStevensonLWGradyKLDecision making in advanced heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart AssociationCirculation2012125151928195222392529

- LunneyJRLynnJFoleyDJLipsonSGuralnikJMPatterns of functional decline at the end of lifeJAMA2003289182387239212746362

- BarclaySMomenNCase-UptonSKuhnISmithEEnd-of-life care conversations with heart failure patients: a systematic literature review and narrative synthesisBr J Gen Pract201161582e496221401993

- HoleBSalemJHow long do patients with chronic disease expect to live? A systematic review of the literatureBMJ Open2016612e012248

- AllenLAYagerJEFunkMJDiscordance between patient- predicted and model-predicted life expectancy among ambulatory patients with heart failureJAMA2008299212533254218523222

- TanvetyanonTLeightonJCLife-sustaining treatments in patients who died of chronic congestive heart failure compared with metastatic cancerCrit Care Med2003311606412544994

- PatrickDLEngelbergRACurtisJREvaluating the quality of dying and deathJ Pain Symptom Manage200122371772611532585

- DonaldsonMSFieldMJMeasuring quality of care at the end of lifeArch Intern Med199815821211289448550

- Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare [webpage on the Internet]Guideline: decision making process of end of life medical care2018 Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/houdou/0000197665.htmlAccessed June 12, 2018