Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterized by airflow obstruction that is not fully reversible; symptoms include chronic cough, sputum production, and dyspnea with exertion. An estimated 50% of the 24 million adults in the USA who have COPD are thought to be misdiagnosed or undiagnosed. Factors contributing to this include a low awareness of COPD and the initial symptoms of the disease among the general population, acceptance of these symptoms as a consequence of aging or smoking, some symptomatic similarity to asthma, and failure of health care personnel to use spirometry for diagnosis. Increased familiarization with COPD diagnosis and treatment guidelines, and proactive identification of patients with increased risk of developing COPD through occupational, environmental, or lifestyle exposures, will assist in a timely, accurate diagnosis and effective treatment, which will consequently improve patient outcomes. This review addresses the issues surrounding the diagnosis and misdiagnosis of COPD, their consequences, and how COPD can be better managed within primary care, including consideration of COPD care in patient-centered medical home and chronic care models.

Introduction: definition of COPD, disease impact on patients, and epidemiology

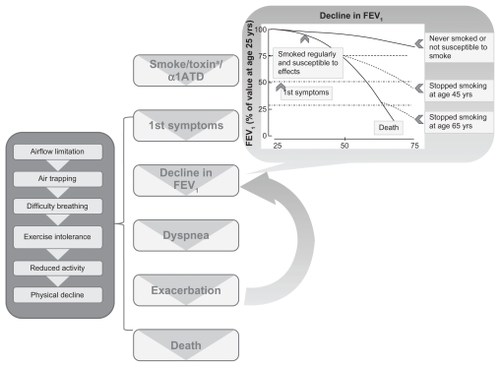

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which is characterized by partially reversible airflow obstruction, is primarily caused by exposure to cigarette smoke and other occupational and environmental pollutants;Citation1 the widely used definitions of COPD are shown in .Citation2–Citation6 The most common symptoms of COPD include chronic cough, abnormal sputum production, and dyspnea with exertion.Citation7 This disease further impacts patients through reduced lung function and reduced quality of life (QoL).Citation8–Citation10 The reduction in lung function is progressive and leads to exercise intolerance, a consequent reduction in activity as patients avoid the discomfort of breathing difficulties, and continued physical decline.Citation11 As the disease advances, symptoms worsen, exacerbations increase in frequency and severity, and lung function is further compromised, causing a downward spiral of events until death eventually occurs (). The patient’s QoL, rate of decline, frequency of exacerbations, and emergency hospitalizations can all be influenced and improved by lifestyle interventions and pharmacologic treatment.Citation3,Citation4,Citation12–Citation14

Figure 1 Disease course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Abbreviation: α1AHD, α1-antitrypsin deficiency.

Table 1 Definitions of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Unfortunately, COPD is not a rare condition and an estimated 50% of the 24 million adults in the USA who have COPD are thought to be misdiagnosed or undiagnosed.Citation15 The aim of this review is to identify the issues surrounding the diagnosis and misdiagnosis of COPD, their consequences, and to address how this situation can be better managed in primary care.

Methods

Medline searches (using PubMed) were carried out using variations and combinations of the following keywords: COPD, undiagnosed, underdiagnosis, prevalence, treatment, patient-centered medical home (PCMH), and asthma. Bibliographies of articles were examined to identify further citations. All nonhuman studies and articles in languages other than English were excluded.

Barriers to COPD diagnosis and treatment

Primary care practitioner– and practice-related barriers

Lack of awareness and knowledge about COPD are major reasons why primary care practitioners (PCPs) and other health care providers may delay or incorrectly diagnose COPD. Results from a survey of American family physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), and physician’s assistants (PAs) (n = 284) indicated that fewer than 50% of this test group reported knowledge or use of COPD diagnosis and treatment guidelines,Citation16 suggesting that familiarity with diagnosis and treatment guidelines, and implementation of the recommendations, could be more widespread.

Often, recognition of COPD does not occur until the disease has progressed to moderate or severe stages,Citation17–Citation19 by which time patients’ symptoms have worsened; they have a poor QoL and a rapidly declining condition. This trend toward late recognition of the disease may persist in spite of a growing body of scientific literature on COPD and updated disease guidelines ().Citation2–Citation5 Guidelines for COPD diagnosis ()Citation2–Citation5 have been developed to help PCPs recognize patients with symptoms and those at risk of developing COPD; therefore awareness of and adherence to these guidelines can help in the early diagnosis of COPD.

Table 2 Comparison of guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Some degree of therapeutic nihilism may also contribute to COPD remaining undiagnosed or undertreated. Data from a test group of 284 physicians, NPs, and PAs showed that only 15% of this group thought that treatment improved COPD symptoms, 13% thought longevity could be extended by COPD treatment, and 3% thought that it reduced exacerbations or that pulmonary rehabilitation was useful.Citation16

Obtaining an early diagnosis of COPD can be challenging for PCPs, as patients with mild COPD and a smoker’s cough may experience little impact on breathing ability and no obvious additional abnormal symptoms.Citation20 Although smoking is the major cause of COPD, risk factors also include exposure to occupational dusts and air pollution, repeated childhood respiratory infections, poor nutrition, and α1-antitrypsin deficiency; therefore, to focus solely on patients who smoke may also contribute to underdiagnosis of COPD. Individuals who are nonsmokers, but who are regularly exposed to secondhand smoke should also be considered at risk of COPD. A study by Bednarek et alCitation21 indicates the importance of considering a diagnosis of COPD for nonsmokers and smokers alike, as detection of COPD in this study would have been reduced by 26% if a “smokers only” criterion had been applied.

Failure to use appropriate diagnostic tools could further contribute to under- or misdiagnosis.Citation22,Citation23 Despite spirometry being a vital tool to establish a diagnosis of COPD, it is widely underutilized, even if available in a medical practice.Citation24,Citation25 A survey of 943 PCPs found that, although 64% of practices had access to spirometry, only 34% regularly used it.Citation26 This situation does not appear to improve when the patient’s disease state is severe enough to warrant hospitalization. A retrospective review of 553 patients, hospitalized with respiratory failure or undergoing ventilator support, with a follow-up period of up to 8 years, found that only 31% of these patients had their diagnosis confirmed by spirometry, despite having a clinical diagnosis of COPD.Citation27 To address these deficiencies, adequate training of PCPs and their practice staff in spirometry use and data interpretation is warranted.Citation25,Citation28

Diagnosis of COPD can also be hampered by diagnostic confusion between asthma and COPD.Citation29 When patients present with cough, shortness of breath, and diminished exercise tolerance, there is a bias toward diagnosing asthma, particularly in women.Citation30 In a study of 597 patients, Tinkelman et alCitation29 found misdiagnosis of asthma and COPD to be common (approximately 40% previously diagnosed with asthma had COPD). Financial factors may also influence the bias toward asthma diagnosis because, in the USA, there is often a “pay for performance” incentive for PCP diagnosis of asthma but there is not for COPD. This is in contrast with the situation in the UK, where incentives have been introduced to promote and improve diagnosis, management, and quality of care for patients with COPD and asthma.Citation31,Citation32 Early indications are that the introduction of these incentive programs is leading to improved quality of care, and that there has been an increase in the use of spirometry and subsequent diagnosis of COPD in the UK.Citation32,Citation33 In the instance of misdiagnosis of COPD as asthma, patients receive treatment that is incorrect, which consequently fails to address their symptoms adequately.Citation31 This is highlighted by a study of 328 patients with assumed asthma that found that 34% of the patients, in fact, had COPD.Citation34

Patient-related barriers

It is important to recognize that patients also display a lack of awareness of COPD: failing to identify symptoms at the start of disease, accepting breathlessness and reduced exercise tolerance as part of normal aging, or attributing cough and sputum to their smoking habit. Unconsciously, such patients adapt their lifestyle to compensate for their deteriorating health, until they have progressed to a stage where they have substantial and irreversible loss of lung function, and the impact is so severe that patients consider seeking medical opinion and intervention.Citation35,Citation36

Evidence from the literature suggests that early diagnosis and appropriate early treatment are beneficial for patients in terms of reduction of symptoms and improvement in QoL.Citation37,Citation38 For example, smoking cessation, which is the most effective intervention for improving disease course and survival in the early stages of COPD, can be encouraged and appropriate therapies started while the patient still has relatively intact lungs.Citation38–Citation40 However, this therapeutic goal may prove elusive, as patients also avoid discussing their COPD symptoms with a PCP because they harbor guilt about their smoking history.Citation41 Such patient concerns can be alleviated by careful discussion to increase their knowledge base, providing support in smoking cessation, and giving priority to COPD treatment, regardless of smoking status,Citation42 similar to the unbiased, proactive treatment given to patients with cardiovascular disease, irrespective of their dietary habits.Citation43 When PCPs take this type of positive action to give treatment early in the course of disease, patient prognosis and QoL can be improved. Despite receiving PCP support, some patients may not be successful in smoking cessation programs, but COPD treatment can still improve the patient’s everyday QoL.Citation17,Citation38,Citation44

Overall, the ongoing gap between PCP-diagnosed and actual COPD cases clearly illustrates that there is room for improvement in the level of knowledge regarding this disease and current treatment practices; examples in the literature exemplify the positive impacts of guideline implementation and of identifying and addressing barriers to diagnosis.Citation45

Making changes in practice to improve the diagnosis and treatment of COPD

Diagnosis

Comprehensive guidelines have been developed by expert teams to aid diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD. The available guidelines include those from the American Thoracic Society/European Thoracic Society (ATS/ERS),Citation2 the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD),Citation4 the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UK,Citation5 and the Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS).Citation3 These guidelines share the same treatment goals but differ in the extent of detail and some recommendations; the ATS/ERS and GOLD guidelines are the most comprehensive, while the CTS guidelines include examples of case management that may occur in everyday practice (). PCPs, PAs, and NPs should be aware of, and familiar with, the COPD guidelines to ensure an early diagnosis and optimum management of COPD.

Another step toward improving the diagnosis of COPD is to have strategies in place to identify patients who may be at risk. There are suggested strategies in the diagnosis and treatment guidelines: the GOLD guidelines recommend a COPD evaluation for patients > 40 years old, with activity limitation, breathlessness, cough, and a history of smoking or occupational/environmental exposure,Citation4 while a lower age of 35 years has been suggested by the “ABC of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease”Citation46 for initiating evaluation of patients who have identified risks of developing COPD and are exhibiting preliminary symptoms.

Although the majority of patients with COPD have a smoking history (more than 50% of smokers will develop COPD),Citation20 the respiratory symptoms of nonsmokers should also be evaluated for COPD diagnosis.Citation47 If a nonsmoking patient has symptoms of cough, shortness of breath, diminished exercise tolerance, and expectoration, questioning by the PCP to establish whether occupational/environmental exposures could have caused the symptoms is recommended and, if these are ruled out, these individuals should be screened for α1-antitrypsin deficiency as a cause of COPD.

Currently, there are new screening initiatives under development and evaluation to identify patients at risk of developing COPD or who are already symptomatic. Such initiatives include a two-step lung function questionnaireCitation48,Citation49 and a three-step screening strategy, which includes the following steps: (1) assess symptoms with a questionnaire; (2) for those patients where Step 1 identifies a risk of COPD, a baseline spirometry test should be performed; and (3) if baseline spirometry shows an abnormality, perform postbronchodilator spirometry. To improve the early diagnosis of patients with COPD, both the two-step and three-step strategies have the potential to be implemented in everyday practice.

Once patients at risk of COPD have been identified, the next step is to follow up with the tools that can confirm diagnosis. It is important to ensure that there are NPs, respiratory therapists, PCPs, or specialists who can efficiently and successfully champion patient spirometry, which is as essential to respiratory practice as electrocardiography is to cardiovascular investigations. As an example of how frequently spirometry might actually be required in diagnosis on a daily basis, if a PCP saw 20 patients per day, who were representative of the population of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III, five patients may have respiratory symptoms and a further three patients may have COPD.Citation50 With decreasing costs for baseline spirometry and the possibility of reimbursement for primary care spirometry,Citation51 the spirometer is becoming an affordable piece of equipment that will rapidly pay for itself, which will enable a wider uptake of this methodology.

Differentiating COPD from asthma

It is essential to differentiate COPD from asthma to ensure correct treatment choices and optimal patient outcomes;Citation52 this can be facilitated by a good understanding of the differences between COPD and asthma. Both COPD and asthma are associated with inflammation and a reduced rate of pulmonary airflow, but they can be distinguished by their differing causes and inflammatory mechanisms. In COPD, irritants, such as smoke, activate lung epithelial cells to release chemotactic factors, which in turn activate pathways that cause elastin degradation, emphysema, mucus hypersecretion, and small airway fibrosis.Citation53 In asthma, triggers cause immunoglobulin activation of mast cells and pathways leading to bronchoconstriction and inflammation.Citation53

COPD and asthma can be differentiated by pre- and postbronchodilator spirometry because airway obstruction is only partially reversible in COPD, while it is fully reversible in asthma.Citation54,Citation55 There may also be differences between the symptoms and medical histories of patients with COPD and asthma. Often, patients with COPD are older than 35 years, have a history of smoking, and may suffer from a persistent, worsening, productive cough. In contrast, asthma can occur at any age but often starts in childhood or adolescence and is characterized by an intermittent dry cough and wheezing. The distinctions between COPD and asthma diagnosis and treatment are summarized in and .Citation3,Citation4,Citation56

Table 3 Differential diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma

Table 4 Differential treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma

Correct diagnosis and treatment can be further complicated in patients where asthma and COPD coexist;Citation4 in a study of 597 patients with obstructive lung disease, almost 25% had both asthma and COPD.Citation29 In such individuals, it is difficult to differentiate between the two diseases, so additional investigations such as chest X-rays may sometimes detect hyperinflation, flattening of diaphragm domes, and basilar markings in COPD, which would normally be absent in patients with asthma.Citation57 Establishing the inflammatory cell profile in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid or sputum may also be used to identify COPD and asthma, as elevated levels of neutrophils are characteristic of COPD but not of asthma, and increased levels of eosinophils are characteristic of asthma but not of COPD.Citation53,Citation55,Citation58

Treating COPD

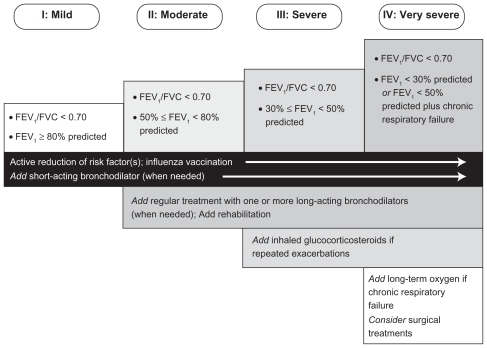

Although not curable, COPD can be treated at any stage of the disease.Citation3 The goals of COPD treatment are to relieve symptoms, prevent disease progression, improve exercise tolerance, improve QoL, prevent and treat exacerbations, and reduce mortality.Citation4 The guidelines that provide information to assist diagnosis of COPD also have recommendations for patient treatment, which include strategies to minimize risk, lifestyle changes, and pharmacotherapy.Citation2–Citation5 The appropriate treatment depends on the patient, and should take into consideration factors such as their current exposure to lifestyle/environmental/occupational risk factors and the severity of disease (). If the patient is a current smoker at the time of diagnosis, support in smoking cessation should be given by the PCP, because it effectively reduces the rate of lung function decline. Providing vaccination against influenza to all patients with COPD, and against pneumonia to patients aged ≥65 years and to those with forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) <40% can also to help reduce the occurrence of exacerbations.

Figure 2 Therapy at progressing stages of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.Citation4

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity.

The pharmacologic treatment of COPD is centered on the use of bronchodilators (β-2 agonists and anticholinergics) and inhaled corticosteroids.Citation4 Depending on the severity of disease, the bronchodilators may be administered as required or as long-term maintenance therapy.Citation4 Combination therapy with bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids is used to achieve effective bronchodilation as disease severity and pulmonary obstruction increase, with inhaled corticosteroids added to the treatment regime when a severe stage of disease is reached.Citation4,Citation59 Patients with severe COPD may also have hypoxemia and/or hypercapnia, which can be improved by the use of supplemental oxygen; this treatment can also lead to improvements in the patients’ exercise capacity.Citation60

These treatments are effective ways of meeting the goals of COPD management. A beneficial addition to pharmacotherapy is participation by the patient in pulmonary rehabilitation, which is recommended for all patients with COPD.Citation3,Citation4,Citation13 A pulmonary rehabilitation program can benefit patients with COPD by providing education and support to change behaviors, such as smoking cessation, improvement in nutrition, and adherence to the prescribed medication regimen. Citation61 Exercise training is a central component of pulmonary rehabilitation, which benefits patients by inducing changes in muscle biochemistry, resulting in improved muscle function.Citation61 These changes delay the fatigue that is associated with lactic acidosis and enable patients to achieve enhanced exercise tolerance and consequential improvement in QoL.Citation61 Exercise training also reduces dyspnea and increases expiratory time, thereby reducing dynamic hyperinflation. Citation61 In addition, a recent review observed that pulmonary rehabilitation can increase motivation, self-efficacy for exercise, and functional capacity for physical activity, thereby enhancing activity and participation in extended activities of daily living.Citation62

The patient-centered medical home – a chronic care model for COPD

Care for many patients with COPD is not optimal because it consists of rescue therapy during hospital visits for episodic exacerbations, with little or no treatment follow-up, rather than the recommended lifestyle change, long-term maintenance pharmacotherapy, and pulmonary rehabilitation. There is a need to move away from the rescue treatment approach toward a more patient-centric care model incorporating regular planned care. The chronic care model (CCM) provides a solution based on high-quality care focused on the following components.Citation63

Enabling patient self-management by providing education, tools, motivation, and support to modify behaviors. Patients should be encouraged to be active participants in their medical care, tracking changes and reporting symptoms.

Establishing a practice team (ie, respiratory therapists, NPs, and PCPs), who give patients regular planned care and access to medical care, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Implementing diagnostic and management guidelines that facilitate disease state management (eg, ATS/ERS, GOLD, NICE, or CTS) and provide continuity of care with referrals for comorbid conditions. The performance against guideline benchmarks should be assessed.

Applying population-based care and providing feedback to the clinical information systems (eg, registries). Although there are limited data on the effectiveness of a

CCM in COPD treatment, systematic reviews have shown that the model significantly reduces hospitalizations and the duration of emergency room visits when two or more of the above components are implemented.Citation63,Citation64 In addition to reducing health care utilization, application of a CCM to patients with COPD has also been shown to improve patients’ QoL.Citation65

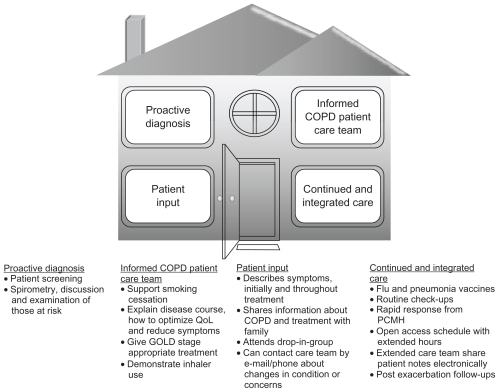

The CCM suggestions for patients with COPD are aligned with the tenets of the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) (), the principles of which were developed jointly by the American Academy of Family Practice, American College of Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American Osteopathic Association.Citation66

Figure 3 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease care in a patient-centered medical home (PCMH).

The PCMH is a refinement of and complement to the CCMCitation67 and involves a multidisciplinary team that is focused on maintaining wellness rather than merely reacting to acute illness.Citation66 The PCMH team is led by a PCP, who guides patient education, is the first point-of-care contact, and oversees continuous care. The core principles inherent to chronic COPD care practiced in a PCMH include proactive diagnosis, informed COPD patient care team, patient input, and continued and integrated care (). Spirometry features prominently as part of the proactive diagnosis tenet. For instance, in managing a patient’s care across different settings over time, a patient could be referred to a pulmonary function laboratory should the practice not have office spirometry or a pulmonologist available. Sharing of medical information via electronic means will also provide all the relevant health care providers with a patient’s pulmonary function readings and other results needed to develop a long-term COPD management plan (eg, risk reduction measures, medication use, increasing physical activity) to improve whole patient care and long-term well-being.Citation68

A central feature of the PCMH is to consider the patient and all their comorbid conditions simultaneously, rather than focusing on just one disease in isolation. This approach is of particular relevance to the care of patients with COPD, who often have multiple comorbidities and resulting polypharmacy. To facilitate care, patients receive enhanced access to care when needed, while ensuring against overtreatment, and also receive extended hours and longer consultations with various team members as appropriate. In addition to traditional consultations, extended care can also include telephone and e-mail access or involvement in a specific patient group. All aspects of the PCMH should be monitored for quality and safety, to enable continual improvements to be made.Citation69,Citation70

Given the lack of research within the USA on the application and effectiveness of CCM and PCMH principles to COPD in the clinic, more research is needed on the clinical integration of evidence-based science in COPD.

Conclusion

Underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis of COPD leave patients with a reduced QoL and, potentially, a more rapidly progressing disease. In this respect, patients do not receive adequate care. Although guidelines and tools for the diagnosis of COPD are readily available, practitioner- and patient-related barriers can prevent an early diagnosis of this disease. Early diagnosis and management of COPD can improve long-term prognosis, giving patients the best opportunities to stop smoking, improve their QoL, reduce their symptoms, and reduce and delay both exacerbations and hospitalizations. To achieve earlier diagnosis and high standards of care for patients with COPD, improvements may be required at several levels within the health care system, including the utilization of patient care models such as the CCM and PCMH, and regular implementation of diagnosis and treatment guidelines by health care teams, together with provision of regular education and support to patients and their care providers.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the editorial assistance of Radhika Bhatia, PhD, of Envision Scientific Solutions in the development of the manuscript; editorial assistance was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim and Pfizer, Inc.

Disclosure

The author has received honoraria for speakers’ bureau participation from Boehringer Ingelheim and Pfizer, Inc. The author exerted scientific control and is solely responsible for the content of the manuscript, having directed the manuscript’s conceptual development and multiple rounds of substantive scientific revisions, and approved the final version for publication.

References

- EisnerMDAnthonisenNCoultasDAn official American Thoracic Society public policy statement: Novel risk factors and the global burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010182569371820802169

- CelliBRMacNeeWStandards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paperEur Respir J200423693294615219010

- O’DonnellDEHernandezPKaplanACanadian Thoracic Society recommendations for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – 2008 update – highlights for primary careCan Respir J200815Suppl A1A8A

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease122010 Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GP:DReport_April112011.pdfAccessed August 22, 2011

- National Clinical Guideline Centre2010Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary careLondonNational Clinical Guideline Centre Available from: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG101/Guidance/pdf/EnglishAccessed August 22, 2011

- World Health Organization (WHO)Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); Factsheet WHO/315112006 Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/fact_sheet/2007/FS_315.pdfAccessed November 12, 2010

- WarrenCPThe nature and causes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a historical perspective. The Christie Lecture 2007, Chicago, USACan Respir J2009161132019262908

- FerrerMAlonsoJMoreraJChronic obstructive pulmonary disease stage and health-related quality of life. The Quality of Life of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Study GroupAnn Intern Med199712712107210799412309

- FletcherCPetoRThe natural history of chronic airflow obstructionBr Med J19771607716451648871704

- JonesPWBrusselleGDal NegroRWHealth-related quality of life in patients by COPD severity within primary care in EuropeRespir Med20111051576620932736

- JonesPWHealth status and the spiral of declineCOPD200961596319229709

- AnthonisenNRSkeansMAWiseRAManfredaJKannerREConnettJEThe effects of a smoking cessation intervention on 14.5- year mortality: a randomized clinical trialAnn Intern Med2005142423323915710956

- MarciniukDDBrooksDButcherSOptimizing pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease–practical issues: a Canadian Thoracic Society Clinical Practice GuidelineCan Respir J201017415916820808973

- AnzuetoAPrimary care management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease to reduce exacerbations and their consequencesAm J Med Sci2010340430931820625276

- WiseRATashkinDPPreventing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: what is known and what needs to be done to make a difference to the patient?Am J Med20071208 Suppl 1S14S2217678939

- YawnBPWollanPCKnowledge and attitudes of family physicians coming to COPD continuing medical educationInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20083231131718686740

- DohertyDEBriggsDDJrChronic obstructive pulmonary disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis, disease course, and prognosisClin Cornerstone2004Suppl 2S51615500179

- StratelisGJakobssonPMolstadSZetterstromOEarly detection of COPD in primary care: screening by invitation of smokers aged 40 to 55 yearsBr J Gen Pract20045450020120615006126

- WaltersJAHansenECWaltersEHWood-BakerRUnder-diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a qualitative study in primary careRespir Med2008102573874318222684

- RadinACoteCPrimary care of the patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-part 1: frontline prevention and early diagnosisAm J Med20081217 SupplS3S1218558105

- BednarekMMaciejewskiJWozniakMKucaPZielinskiJPrevalence, severity and underdiagnosis of COPD in the primary care settingThorax200863540240718234906

- DeromEvan WeelCLiistroGPrimary care spirometryEur Respir J200831119720318166597

- KaminskyDAMarcyTWBachandMIrvinCGKnowledge and use of office spirometry for the detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by primary care physiciansRespir Care200550121639164816318645

- FrankTLHazellMLLinehanMFFrankPIThe diagnostic accuracies of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in general practice: The results of the MAGIC (Manchester Airways Group Identifying COPD) studyPrim Care Respir J200615528629316978921

- MoorePLPractice management and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary careAm J Med20071208 Suppl 1S23S2717678940

- FosterJAYawnBPMaziarAJenkinsTRennardSICasebeerLEnhancing COPD management in primary care settingsMedGenMed2007932418092030

- DamarlaMCelliBRMullerovaHXPinto-PlataVMDiscrepancy in the use of confirmatory tests in patients hospitalized with the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or congestive heart failureRespir Care200651101120112417005056

- BoltonCEIonescuAAEdwardsPHFaulknerTAEdwardsSMShaleDJAttaining a correct diagnosis of COPD in general practiceRespir Med200599449350015763457

- TinkelmanDGPriceDBNordykeRJHalbertRJMisdiagnosis of COPD and asthma in primary care patients 40 years of age and overJ Asthma2006431758016448970

- ChapmanKRTashkinDPPyeDJGender bias in the diagnosis of COPDChest200111961691169511399692

- WalkerPPMitchellPDiamanteaFWarburtonCJDaviesLEffect of primary-care spirometry on the diagnosis and management of COPDEur Respir J200628594595216870668

- SteelNMaiseySClarkAFleetcroftRHoweAQuality of clinical primary care and targeted incentive payments: an observational studyBr J Gen Pract20075753944945417550669

- SmithCJGribbinJChallenKBHubbardRBThe impact of the 2004 NICE guideline and 2003 General Medical Services contract on COPD in primary care in the UKQJM2008101214515318180254

- GriffithsCFederGWedzichaJFosterGLivingstoneAMarloweGSFeasibility of spirometry and reversibility testing for the identification of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on asthma registers in general practiceRespir Med1999931290390810653053

- HalpinDMMiravitllesMChronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the disease and its burden to societyProc Am Thorac Soc20063761962316963544

- MapelDWFrostFJHurleyJSAn algorithm for the identification of undiagnosed COPD cases using administrative claims dataJ Manag Care Pharm200612645746516925453

- BriggsDDJrChronic obstructive pulmonary disease overview: prevalence, pathogenesis, and treatmentJ Manag Care Pharm2004104 SupplS3S1015253681

- DecramerMCooperCBTreatment of COPD: the sooner the better?Thorax201065983784120805184

- SundbladB-MLarssonKNathellLLow awareness of COPD among physiciansClin Respir J200821111620298299

- ShahabLJarvisMJBrittonJWestRPrevalence, diagnosis and relation to tobacco dependence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a nationally representative population sampleThorax200661121043104717040932

- CelliBRChronic obstructive pulmonary disease: from unjustified nihilism to evidence-based optimismProc Am Thorac Soc200631586516493152

- HalliwellJMulcahyPBuetowSBrayYCosterGOsmanLMGP discussion of prognosis with patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a qualitative studyBr J Gen Pract20045450990490815588534

- PearsonTKopinLBridging the treatment gap: improving compliance with lipid-modifying agents and therapeutic lifestyle changesPrev Cardiol20036420421114605514

- AnthonisenNRConnettJEKileyJPEffects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV1. The Lung Health StudyJAMA199427219149715057966841

- DeprezRKinnerAMillardPBaggottLMellettJLooJLImproving quality of care for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePopul Health Manag200912420921519663624

- CurrieGPLeggeJSABC of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. DiagnosisBMJ200633275521261126316735338

- CelliBRHalbertRJNordykeRJSchauBAirway obstruction in never smokers: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination SurveyAm J Med2005118121364137216378780

- HananiaNAManninoDMYawnBPPredicting risk of airflow obstruction in primary care: Validation of the lung function questionnaire (LFQ)Respir Med201010481160117020226647

- YawnBPMapelDWManninoDMMartinezFJDalalAAPerformance of a brief, self-administered questionnaire (Lung Function Questionnaire) to identify patients at risk of airflow obstruction as potential candidates for spirometry: scoring and cut point [abstract]Am J Respir Crit Care Med2009179A1476

- ManninoDMFordESReddSCObstructive and restrictive lung disease and functional limitation: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition ExaminationJ Intern Med2003254654054714641794

- BelferMHOffice management of COPD in primary care: a 2009 clinical updatePostgrad Med20091214829019641274

- SussmanRPart I: Identifying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients with respiratory symptomsCurr Med Res Opin200723Suppl 3S5S1217925063

- BarnesPJMechanisms in COPD compared with asthmaBreathe200852134143

- RabeKFHurdSAnzuetoAGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007176653255517507545

- YawnBPDifferential assessment and management of asthma vs chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseMedscape J Med20091112019295941

- British Thoracic Society, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines NetworkBritish guideline on the management of asthmaThorax200863Suppl 4iv1iv12118463203

- DewarMCurryRWJrChronic obstructive pulmonary disease: diagnostic considerationsAm Fam Physician200673466967616506711

- RonchiMCPiraginoCRosiEAmendolaMDurantiRScanoGRole of sputum differential cell count in detecting airway inflammation in patients with chronic bronchial asthma or COPDThorax19965110100010048977600

- HananiaNAThe impact of inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting β-agonist combination therapy on outcomes in COPDPulm Pharmacol Ther200821354055018280761

- AlbertPCalverleyPMDrugs (including oxygen) in severe COPDEur Respir J20083151114112418448506

- CasaburiRZuWallackRPulmonary rehabilitation for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2009360131329133519321869

- ZuWallackRLHow do we increase activity and participation in our patients?Semin Respir Crit Care Med200930670871219941228

- AdamsSGSmithPKAllanPFAnzuetoAPughJACornellJESystematic review of the chronic care model in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevention and managementArch Intern Med2007167655156117389286

- SteutenLMLemmensKMNieboerAPVrijhoefHJIdentifying potentially cost effective chronic care programs for people with COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2009418710019436687

- BramanSSLeeDWPrimary care management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an integrated goal-directed approachCurr Opin Pulm Med2010162838820010105

- American Academy of Family PhysiciansJoint principles of the Patient- Centered Medical HomeDel Med J2008801212218284087

- WagnerEHChronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness?Eff Clin Pract1998112410345255

- FromerLBarnesTGarveyCOrtizGSaverDFYawnBInnovations to achieve excellence in COPD diagnosis and treatment in primary carePostgrad Med2010122515016420861599

- Patient Centered Primary Care CollaborativeEvidence of quality: evidence on the effectiveness of the Patient-Centered Medical Home on quality and cost [webpage on the Internet]Washington, DCPatient- Centered Primary Care Collaborative; nd Available from: http://www.pcpcc.net/content/evidence-qualityAccessed November 12, 2010

- StangeKCNuttingPAMillerWLDefining and measuring the patient-centered medical homeJ Gen Intern Med201025660161220467909