Abstract

Current treatments have failed to stem the continuing rise in health care resource use and fatalities associated with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Reduction of severity and prevention of new exacerbations are therefore important in disease management, especially for patients with frequent exacerbations. Acute exacerbation treatment includes short-acting bronchodilators, systemic corticosteroids, and antibiotics if bacterial infections are present. Oxygen and/or ventilatory support may be necessary for life-threatening conditions. Rising health care costs have provided added impetus to find novel therapeutic approaches in the primary care setting to prevent and rapidly treat exacerbations before hospitalization is required. Proactive interventions may include risk reduction measures (eg, smoking cessation and vaccinations) to reduce triggers and supplemental pulmonary rehabilitation to prevent or delay exacerbation recurrence. Long-term treatment strategies should include individualized management, addressing coexisting nonpulmonary conditions, and the use of maintenance pharmacotherapies, eg, long-acting bronchodilators as monotherapy or in combination with inhaled corticosteroids to reduce exacerbations. Self-management plans that help patients recognize their symptoms and promptly access treatments have the potential to prevent exacerbations from reaching the stage that requires hospitalization.

Introduction

Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) manifest as aggravated respiratory symptoms that can negatively impact a patient’s disease trajectory, often with grim consequences to the individual and society. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defines exacerbations as “an event in the natural course of the disease characterized by a change in the patient’s baseline dyspnea, cough, and/or sputum that is beyond normal day-to-day variations, is acute in onset, and may warrant a change in regular medication.”Citation1 Variations in defining, reporting, or diagnosing episodes may mask the true health and economic burden of exacerbations. Nevertheless, exacerbations are expected to increase in tandem, with projections that deaths from underlying COPD will rise by more than 30% over the next decade without interventions to cut risks.Citation2 Compounding the societal health impact are the staggering costs involved in treating acute exacerbations, especially if they are severe in nature and therefore warrant hospitalization. The total cost of caring for COPD in the United States is rapidly approaching US$50 billion per year. Most estimates suggest that 70% of that cost relates to treating exacerbations, particularly severe episodes requiring hospitalization and often intensive care.Citation3

Exacerbation-prone individuals may be negatively affected in terms of a decreased quality of life, increased hospitalization, and premature deaths, either as a consequence of COPD or coexisting diseases.Citation4 Exacerbation frequencies and associated hospitalizations in those who are prone to exacerbations typically range from 0.5 to 5.2 exacerbations (depending on definitions used) and from 0.09 to 2.40 hospitalizations per year, respectively.Citation5–Citation7 Patients with severe COPD who have frequent exacerbations (≤ 6-month intervals; > three per year) have a more rapid decline in lung function and worse health-related quality of life than those who experience infrequent exacerbations.Citation8 However, data from the Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) initiative suggest that there is a frequent-exacerbation phenotype that is independent of disease severity.Citation9 Exacerbation duration is variable but may last up to 5 weeks,Citation10 and the impact can be prolonged or permanent;Citation11 there is also a high risk of a recurring exacerbation in the 8-week period following an index event.Citation12 The devastating consequences of exacerbations are underscored by high rates of relapse (22%–32% of emergency department patients visit the department again),Citation13 1-year (25%) and 5-year (44%) hospital readmissions,Citation14 and overall treatment failures (32%),Citation15 as well as high exacerbation-related fatalities (2.5%–10.0%), increasing in intensive care unit patients to 20%–24%.Citation16,Citation17

Reports are beginning to illuminate the gap between guideline-recommended and actual treatment and follow-up care of hospitalized COPD patients. One retrospective analysis of these patients showed that prescribed respiratory drugs were underused, overused, or misused.Citation18 A separate retrospective cohort study showed that hospitalized patients with acute exacerbations received adequate care, but that there were opportunities to improve treatment in both the inpatient and outpatient settings.Citation19 Recognition of the cost-prohibitive nature and frequent treatment of recurrent exacerbations in hospitals has added to the interest in treating milder or frequent episodes in the primary care setting. Ultimately we will need to balance the cost of potential preventive therapies versus the benefit of preventing exacerbations. The aim of this review is to describe strategies that may improve the prevention and treatment of exacerbations.

Triggers and effects of COPD exacerbations

The transition from stable-state COPD to onset of an exacerbation typically involves amplified airway inflammation.Citation1 Infections of the tracheobronchial tree (viral and bacterial), exposure to air pollution (eg, inhalation of tobacco smoke, occupational and environmental exposure to particulates or noxious gases), and suboptimal treatment adherence account for most identifiable causes of exacerbations.Citation1 Exacerbations triggered by respiratory viral mono- or coinfections are more likely to be severe, prolonged, and associated with hospital admissions compared with episodes where respiratory viruses were not detected. Further investigation is needed to establish whether chronic respiratory viral infection of stable COPD patients’ airways predisposes patients to exacerbations.Citation20 Many exacerbations are triggered by a bacterial infection caused by, for example, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.Citation20 Elevated levels of the latter pathogen are more likely to be associated with severe COPD or when systemic steroids and/ or antibiotics had been prescribed in the preceding months.Citation21 In addition, Bordetella pertussis, the re-emergent pathogen responsible for pertussis (whooping cough), has been associated with 31% of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis, according to one pilot study.Citation22 While infections are the most common cause of exacerbations,Citation1 the apparent increased susceptibility to this etiologic factor in patients with COPD is not well understood. Recent evidence suggests that an altered airway epithelial cell phenotype may contribute to increased susceptibility to viral infection in patients with COPD compared with control subjects.Citation23

Exacerbations may also increase the risk of nonpulmonary events and related mortality. Specific molecular pathways culminating in exacerbations remain to be elucidated, but elevated systemic inflammatory markers are often present during acute exacerbations and have been associated with a small but statistically significant risk of stroke and cardiovascular events.Citation24 Worsening bronchoconstriction from an exacerbation may elevate pulmonary artery pressures, placing an increased burden on the right side of the heart.Citation24 A higher post-exacerbation myocardial infarction incidence has been reported in patients with more frequent exacerbations, although the reasons for this finding remain unclear.Citation24 The recent ECLIPSE study showed that more frequent exacerbations were also associated with greater impairment in health status.Citation9

Patients who have frequent exacerbations have been defined as having more than the annual median number of episodes for a given study, usually two steroid- and/or antibiotic- requiring or three symptom-defined exacerbations.Citation20 These patients can exhibit elevations in specific blood and airway-derived biomarkers compared with those who have infrequent exacerbations,Citation25,Citation26 generally have a faster decline in functional status,Citation27 are more prone to rehospitalization,Citation14 and are more likely to be houseboundCitation20 than those who have infrequent exacerbations. Patients hospitalized with COPD exacerbations are also more likely to have coexisting pneumonia and diabetes than hospitalized patients without COPD.Citation28

Diagnosis of an exacerbation

Diagnosis and staging of COPD exacerbations depend on symptom-based criteria and/or health care resource utilization (). Since increasing confusion may be part of respiratory compromise, it may also be beneficial to assess a patient’s mental status during evaluation (). Of the known hospitalization indicators, escalating respiratory distress, onset of respiratory acidosis, significant nonpulmonary conditions, and the need for ventilatory (invasive or noninvasive mechanical) support are especially important, since they are associated with an increased risk of death.Citation1

Table 1 Commonly used definitions of exacerbation severityCitation33,Citation34

Table 2 Hospitalization indicators and evaluations of exacerbationsCitation1

While a severe exacerbation is almost always identified and treatment provided, many milder events go unreported by patientsCitation29 or are labeled by clinicians as upper respiratory tract infections or acute bronchitis. Recognizing and appropriately treating all exacerbations, including milder symptom worsening reported by patients, may help prevent future exacerbations. Composite indices can help identify patients at increased risk of developing a future exacerbation. Examples include indices for (1) BODE (body mass index, airflow obstruction [forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)], dyspnea, and exercise capacity)Citation30 and (2) DOSE (dyspnea scale, airflow obstruction [FEV1], smoking status [current versus former], and prior exacerbation frequency).Citation31 In addition, the Exacerbations of Chronic Pulmonary Disease Tool, a Patient-Reported Outcome measure initiative, has been designed to standardize evaluations of the frequency, severity, and duration of acute exacerbations of COPD and chronic bronchitis. A recent observational study suggests that this 14-item digital diary is reliable, valid, and sensitive to change with exacerbation recovery.Citation32

Since no single test can fulfill all requirements, additional evaluations are needed to accurately identify exacerbation-prone patients. Inadequate recording of relevant factors (medical history, risk factors, exercise tolerance), lack of equipment, clinicians with limited training, as well as patients with multiple chronic conditions may further complicate diagnosis.

Investigational biomarkers associated with exacerbation etiology, severity, and recovery can potentially augment the current diagnostic toolkit. One example is the hormone precursor procalcitonin, which is elevated in serum when bacterial infections are present.Citation33 Ongoing studies are needed to assess the routine use of procalcitonin to diagnose these exacerbations (in order to reduce patient exposure to antibiotics); its use has not yet been recommended by guidelines. Further studies are also needed to assess the value of routine testing for biomarkers found in association with exacerbations, such as fractional exhaled nitric oxide and C-reactive protein (CRP).Citation33–Citation35

Treatment of acute exacerbations

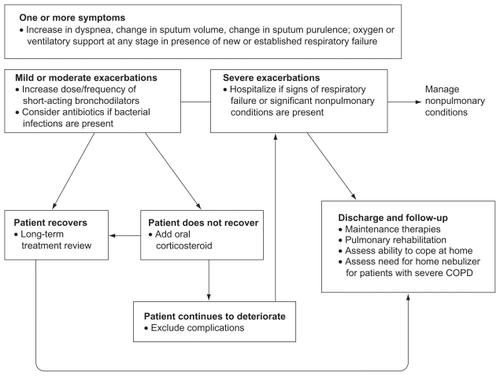

Given the frequently fatal nature of COPD exacerbations, they must be recognized early and accurately to allow prompt initiation of therapy. Early detection and treatment of exacerbations can improve patients’ wellbeing and health-related quality of life and reduce hospitalizations.Citation1 The recommended treatment algorithm for exacerbations is delineated in .Citation1,Citation36,Citation37 Pharmacotherapy is intended to relieve dyspnea, reduce airway inflammation, improve lung function, and eradicate infections, potentially moderating disease progression. A reliable predictor of a recurrent exacerbation is a history of previous exacerbations.Citation6,Citation9

Figure 1 Treatment algorithm for patients with exacerbations.

Adapted from the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease guidelines,Citation1 Anthonisen et al,Citation36 and Celli et al.Citation37

Bronchodilators

The first step in the treatment of an exacerbation is to increase the dose of inhaled bronchodilator to decrease dyspnea. Citation1 Short-acting β-agonists (SABAs) are used as needed because they have a rapid onset of action on bronchoconstriction. Prescriptions of these bronchodilators are subject to consideration of known adverse events for SABAs (eg, hypokalemia).Citation1 Combining SABAs with inhaled short-acting anticholinergics (SAACs) may have additional benefit. Common side effects of anticholinergics include dry mouth and constipation.Citation38 If patients are already receiving maintenance pharmacotherapies, some caution needs to be exercised when adding regular doses of SABAs or SAACs, since side effects could increase. Methylxanthine derivatives may play a role as second-line therapies in selected cases where patients are poorly responsive to SABAs or SAACs;Citation1 however, their significant potential side effects when used in high doses or combined with other common chronic disease therapies warrant close clinical and biochemical monitoring for possible adverse events.

Corticosteroids

The major use for systemic steroids is in combination with other therapies, eg, bronchodilators, during an acute exacerbation. Citation1 No steroid taper is required for a short course of systemic steroid therapy, per GOLD guidelines.Citation1 Recent data suggest that oral corticosteroids are as effective as intravenous corticosteroids in patients hospitalized with exacerbations; however, prolonged treatment with oral corticosteroids (>10 days) does not result in greater efficacy and increases the risk of side effects such as hyperglycemia and muscle atrophy.Citation1 While an approved inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/long-acting β-agonist (LABA) combination is used in the context of preventing the next exacerbation, the GOLD guidelines state that the ICS, budesonide, “alone, or in combination with formoterol may be an alternative (although more expensive) to oral glucocorticosteroids in the treatment of exacerbations.”Citation1

Antibiotics

Bacterially triggered exacerbations are usually amenable to appropriate antibiotic therapy.Citation1 Current antibiotic recommendations () will depend on the bacterial strains that are responsive or resistant to antimicrobial therapies. Relevant factors that may guide specific antibiotic choices are drug penetration into pulmonary airways, efficacy of microbial clearance, treatment duration, likelihood of pathogen recurrence, and any drug-related adverse events.Citation39

Table 3 Antibiotic treatment in exacerbation of COPD

Adding antibiotics to corticosteroid therapy has been shown to prolong the time to the next exacerbation and to reduce the risk of a new exacerbation versus corticosteroid use alone.Citation40 One meta-analysis showed that treatment duration (≤ 5 days) did not affect the cure rates attributed to broad-spectrum antibiotics,Citation41 whereas another meta-analysis showed a lower risk of treatment failure for broad-spectrum versus narrow-spectrum antibiotics.Citation42 A randomized trial of a broad spectrum antibiotic, doxycycline, added to systemic corticosteroids in selected patients hospitalized with acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD), demonstrated similar clinical success on day 30 in intent-to-treat (odds ratio 1.3, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.8–2.0) and per-protocol patients, but on day 10 those receiving doxycycline demonstrated improvement in symptom score, microbiologic outcome, and clinical cure.Citation43 In this study, patients with higher CRP levels treated with antibiotics had a better response than those in the placebo group, suggesting a potential future importance for this biomarker in defining therapeutic paths.

Oxygen and noninvasive ventilation

Oxygen requirements typically increase during exacerbations. Oxygen supplementation and/or ventilation should be considered for patients who are experiencing signs of respiratory failure (eg, worsening hypercapnia, hypoxemia, acidosis, or pulmonary embolism) or have coexisting conditions such as myocardial infarction or sepsis.Citation44 Long-term oxygen therapy (indicated if saturation level is below 88%) can correct hypoxemia in patients with very severe COPD and improve overall health status.Citation1 If the patient is discharged from the hospital on oxygen or on higher amounts of oxygen than on admission, the oxygen requirement must be reevaluated as the patient improves, in order to better define long-term requirements.

If patients with severe exacerbations are poorly responsive to oxygen supplementation alone, they may be candidates for ventilatory support to avoid intubation, including noninvasive ventilation (NIV) in the case of eligible individuals.Citation1 Although the prognosis is poor for all patients requiring ventilatory support, evidence based on data from a subset of patients suggests that NIV reduces morbidity and mortality rates and intensive care unit or hospital lengths of stay.Citation45

Reduction/prevention of exacerbations

Although patients hospitalized with severe exacerbations usually receive recommended care, most patients are not discharged with appropriate support and medications.Citation19 It is debatable whether health care insurances will continue to pay for potentially avoidable COPD-related hospital read-missions. Thus, there is a growing impetus to prevent or reduce exacerbation severity in the primary care outpatient setting to avoid hospitalization. Patients with exacerbations may benefit from risk reduction measures and maintenance pharmacotherapies, supplemented with self-management plans, as part of pulmonary rehabilitation (PR).

Risk reduction

Results from a large-scale retrospective analysis of current and former smokers showed that smoking cessation significantly reduced exacerbations after adjusting for age, comorbidities, disease severity, and socioeconomic status (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 0.78, 95% CI 0.75–0.87).Citation46 These data support guideline recommendations for smoking cessation as a risk reduction measure regardless of disease status.Citation1

Seasonal influenza and pneumococcal pneumonia vaccinations should be standard, as appropriate for COPD patients, according to the GOLD guidelines.Citation1 Elderly COPD patients (aged ≥ 65 years), in particular, suffer significant adverse events from influenza and derive health benefits from vaccinations in the form of fewer hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and fatalities. Immunizations in this high-risk group should, therefore, be a priority for all clinicians.Citation47 Consideration should also be given to providing a one-time dose of the tetanus-diphtheria-acellular-pertussis (Tdap) vaccine to previously unvaccinated individuals with COPD (aged < 65 years), based on medical and other indications;Citation48 for example, in the face of a pertussis epidemic in local children. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends Tdap for older individuals (aged ≥ 65 years) not previously immunized with this vaccine who anticipate close contact to infants (aged < 12 months).Citation48,Citation49

Antibiotic prophylaxis with a low-dose macrolide has emerged as another possible therapeutic option for reducing exacerbation frequency. In a 12-month study of COPD patients experiencing moderate and/or severe exacerbations (35% experienced three or more exacerbations in the year before recruitment), twice-daily administration of erythromycin, was associated with a significant reduction in exacerbations compared with placebo.Citation50 Results from a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed that long-term, once-daily administration of azithromycin, in addition to usual care, decreased the frequency of AECOPD (1.47 versus 1.84/patient-year, P = 0.004) and improved the quality of life of exacerbation-prone COPD patients.Citation51

Maintenance pharmacotherapies

Results from two megatrials, Understanding Potential Long-term Impacts on Function with Tiotropium (UPLIFT®)Citation52 and Towards a Revolution in COPD Health (TORCH),Citation53 have shown a benefit for a long-acting anticholinergic (LAAC), tiotropium, and a LABA/ICS combination (salmeterol/fluticasone) in reducing key clinical endpoints, including exacerbations. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved tiotropium to reduce exacerbations in COPD patients and salmeterol/fluticasone to reduce exacerbations in COPD patients with a history of exacerbations. In the UPLIFT trial, median time to the first exacerbation was 16.7 months (95% CI 14.9–17.9) in the tiotropium group versus 12.5 months (95% CI 11.5–13.8) in the placebo group (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.81–0.91). Tiotropium treatment was also associated with a 14% decrease in the mean number of exacerbations versus placebo (P < 0.001).Citation52

A study by Niewoehner et al showed tiotropium reduced the proportion of patients with moderate to severe COPD experiencing exacerbations and may reduce health care utilization compared with placebo.Citation54 In this study, the treatment groups received “usual care” as well as study treatment that could include respiratory medications other than anticholinergic bronchodilators, which may reflect “real-world” practice.Citation54 In the 3-year TORCH study, salmeterol/ fluticasone (50 μg/500 μg) treatment versus placebo resulted in a rate ratio for exacerbations of 0.75 (95% CI 0.69–0.81; P < 0.001), which is a reduction of 25% in affected individuals. Citation53 Another 1-year study showed that treatment with salmeterol/fluticasone (50 μg/250 μg) reduced exacerbation rates in patients with moderate to severe COPD by 30.5% compared with salmeterol.Citation55 A direct comparison of tiotropium (18 μg) and salmeterol/fluticasone (50 μg/500 μg) in patients with severe to very severe COPD showed no statistical difference in exacerbation rates over 2 years.Citation56 However, tiotropium (18 μg) was more effective than salmeterol (50 μg) in all assessed exacerbation endpoints and across all the major subgroups, according to a separate 1-year comparative study of only the LAAC and LABA given to patients with moderate to severe COPD and a history of exacerbations.Citation57

Another LABA/ICS combination, budesonide/formoterol (not FDA-indicated for COPD exacerbations), administered to patients with moderate to severe COPD, reduced systemic steroid-requiring exacerbations versus formoterol alone in a 6-month study (20%–25% exacerbation reductions with budesonide-containing treatments versus formoterol or placebo alone).Citation58 Similarly, a 1-year study of the treatment effects of these agents showed 25%–29% lowered exacerbation rates (with budesonide-containing therapies) beyond reductions achieved with formoterol alone.Citation59 In addition, budesonide/formoterol plus tiotropium specifically reduced the number of exacerbations by 62% versus tiotropium treatment alone.Citation60 Roflumilast, an oral phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, is indicated in the United States as a treatment to reduce the risk of COPD exacerbations in patients with severe COPD associated with chronic bronchitis and a history of exacerbations (up to 18% exacerbation reduction noted in studies).Citation61

Adherence

Adherence to disease management guidelines by clinicians and individualized patient education to optimize adherence to medications and nonpharmacological treatments may be key factors in lowering exacerbation rates. Suboptimal medication adherence, whether as a consequence of patient-specific factors (costs, physical or psychosocial factors, or insufficient education by the physician),Citation62–Citation64 less-than-optimal implementation of guideline- recommended therapy by physicians,Citation65 or polypharmacy due to comorbidities,Citation64 remains a tremendously important issue. Prescribing appropriate treatment regimens can only be effective if the patient continues to take their medication. In a survey of over a 1000 COPD patients, 50% had 6–10 comorbidities, over 30% were receiving 5–10 non-COPD medications, and over 20% were receiving over 11 non-COPD medications.Citation64 Inhaler misuse may also contribute to suboptimal medication adherence.Citation66 It is important for clinicians to keep all these factors in mind, since adherence to inhaled COPD medications has been correlated with reduced hospital admissions and mortality risk due to exacerbations.Citation1

Pulmonary rehabilitation

PR as an adjunctive therapy can improve dyspnea, exercise tolerance, and health-related quality of life, as well as reduce recurrent exacerbations and, hence, the risk of hospitalization in some patients.Citation1 Stage-appropriate PR should include one or more aspects of disease and inhaler education, optimization of daily living activities, self-management of symptoms, anxiety and stress control, oxygen therapy, guidance for early detection and treatment of COPD exacerbations, smoking cessation, nutrition, structured exercise, and increased physical activity at home.Citation67 A systematic review has shown that PR has the potential to reduce the number of exacerbations and associated hospital visits as well as their severity.Citation68 In a multicenter study, tiotropium plus PR-treated patients experienced fewer exacerbations and exacerbation days, and improvements in health-related quality of life, relative to the tiotropium-only group.Citation69 Clinically meaningful changes in exercise tolerance, dyspnea, and fatigue were observed in United Kingdom patients treated for exacerbations in a hospital setting and enrolled 10 days post discharge in an 8-week PR program (10% of rehabilitated patients versus 42% of usual-care patients; P = 0.01). Shuttle-walk distance was nearly doubled in rehabilitated patients, and dyspnea and fatigue were significantly reduced.Citation70

Beginning PR after resolution of an acute exacerbation resulted in reduced health care utilization and costs in a separate United States study.Citation71 Since this is, in essence, a behavioral intervention, durable health benefits can be reaped only if a patient can sustain behavior and lifestyle changes over the long term.

Cardiac protective therapies

Cardiovascular events are extremely common in COPD patients and impact morbidity and mortality.Citation64,Citation72,Citation73 These diseases cause 25% of deaths and nearly 50% of hospitalizations in patients with mild to moderate COPD, as well as significantly increasing the duration of hospitalization and risk of premature death in patients with severe exacerbations.Citation73,Citation74 It has also been suggested that all patients who have frequent exacerbations may need treatments to reduce cardiovascular events during stable disease periods.Citation75

European guidelines state that COPD is not a contraindication for evidence-based cardiovascular disease treatment with β-blockers;Citation76 however, their underuse in COPD has classically been associated with concern over the risk of worsening bronchospasm. Emerging evidence suggests that treatment with cardioselective β-blockers is safe, well tolerated, and reduces the risk of exacerbations and premature deaths in COPD patients with coexisting cardiovascular disease.Citation77,Citation78 In the absence of larger prospective randomized clinical trials, the decision to use β-blockers in COPD patients must be made very carefully. However, the concept that bronchodilators (eg, β-agonists) and β-blockers could both decrease exacerbations further emphasizes the complexity of these events.

Self-management

Self-management plans empower patients with a history of exacerbations by teaching problem-solving skills, including recognition and interpretation of symptom changes, and next steps (eg, seeking access to appropriate care). Patient education is a vital aspect of guided self-management in order to address some of the issues underlying suboptimal medication adherence, such as compromised inhaler technique (as described in detail elsewhere).Citation66

Written action plans are also important components of self-management and could be part of PR or an existing chronic care program. One example currently being evaluated by the Canadian Thoracic SocietyCitation79 provides patients with advice on self- or medical-care visits, as appropriate. Analyses of the benefits of action plans have produced variable results, mainly because of the heterogeneity in plans, study populations, follow-up time, and outcome measures,Citation80 although two separate analyses showed that self-management plans increased appropriate treatmentCitation81 and reduced exacerbation recovery time.Citation82 Where feasible, a 24-hour telephone support service may reduce the number of hospitalizations.Citation83 Other forms of support can be considered to supplement self-management plans (eg, Web-based consultation services or videophones); however, this type of home monitoring may be expensive to set up, and many older patients may not be able to master the technology. While self-management plans are very important, their benefits have yet to be evaluated in patients immediately following hospitalization or in those who are prone to frequent exacerbations.

Lung volume reduction surgery

Lung volume reduction surgery has been shown to improve the quality of life, exercise capacity, and survival in a carefully selected group of patients with upper-lobe predominant emphysema.Citation84 The evidence suggests that patients who meet pre-specified criteria for surgery and undergo the procedure may receive an additional benefit in terms of a reduction in exacerbations, potentially by improving respiratory mechanics and decreasing the volume of trapped air from hyperinflated regions of the lungs.Citation85

Summary

Many patients with COPD delay reporting exacerbations, which leads to detrimental consequences to their quality of life.Citation29 Severe exacerbations, usually involving hospitalization, are associated with enormous health and socioeconomic costs. Short-acting bronchodilators and oxygen are prescribed to relieve dyspnea, corticosteroids to decrease inflammation during an acute exacerbation, and appropriate antibiotic therapy to treat bacterial infections. A long-term treatment plan should include one or more available classes of drugs (LAAC, LABA [alone or in combination], an ICS/ LABA combination, and phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor) that represent maintenance pharmacotherapies to prevent future exacerbations, as well as management of coexisting nonpulmonary conditions and strategies to optimize adherence to inhaled medications. Supplementary PR may be important in preventing or delaying the recurrence of exacerbations in some patients after they have recovered from an acute event. Self-management plans, as part of PR or a chronic care program, may contribute to a reduction in the frequency and severity of exacerbations.

Conclusion

Exacerbations affect patient longevity and quality of life, thereby dramatically contributing to the cost of care for affected individuals. By helping to prevent, recognize, and appropriately treat these events, clinicians can have a major impact on the course of COPD.

Acknowledgments

Manuscript preparation, including medical writing assistance, which was provided by Zeena Nackerdien, PhD, of Envision Scientific Solutions, was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc and Pfizer Inc. The article reflects the concepts of the authors and is their sole responsibility. It was not reviewed by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc and Pfizer Inc, except to ensure medical and safety accuracy.

Disclosure

Dr Yawn participated in COPD studies from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and GlaxoSmithKline, for which Olmsted Medical Center received funding, and served on an advisory meeting for Novartis, with honoraria paid to Olmsted Medical Center. Dr Thomashow has been a member of advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Intermune, Forrest Pharmaceuticals, and Talecris.

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD [updated December 2010] Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLDReport_April112011.pdfAccessed April 13, 2011

- World Health OrganizationChronic obstructive pulmonary disease Fact sheet No. 315. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/guidelines-global-strategy-for-diagnosis-management.htmlAccessed August 26, 2011

- ToyELGallagherKFStanleyELSwensenARDuhMSThe economic impact of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and exacerbation definition: a reviewCOPD20107321422820486821

- ManninoDMBuistASGlobal burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trendsLancet2007370958976577317765526

- BourbeauJFordGZackonHPinskyNLeeJRubertoGImpact on patients’ health status following early identification of a COPD exacerbationEur Respir J200730590791317715163

- DonaldsonGCWedzichaJACOPD exacerbations.1: EpidemiologyThorax200661216416816443707

- O’ReillyJFWilliamsAEHoltKRiceLDefining COPD exacerbations: impact on estimation of incidence and burden in primary carePrim Care Respir J200615634635317064963

- Soler-CatalunaJJMartinez-GarciaMARoman SanchezPSalcedoENavarroMOchandoRSevere acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseThorax2005601192593116055622

- HurstJRVestboJAnzuetoASusceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2010363121128113820843247

- SeemungalTADonaldsonGCBhowmikAJeffriesDJWedzichaJATime course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med200016151608161310806163

- StevensonNJWalkerPPCostelloRWCalverleyPMLung mechanics and dyspnea during exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2005172121510151616166620

- HurstJRDonaldsonGCQuintJKGoldringJJBaghai-RavaryRWedzichaJATemporal clustering of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009179536937419074596

- AdamsSGMeloJLutherMAnzuetoAAntibiotics are associated with lower relapse rates in outpatients with acute exacerbations of COPDChest200011751345135210807821

- McGhanRRadcliffTFishRSutherlandERWelshCMakeBPredictors of rehospitalization and death after a severe exacerbation of COPDChest200713261748175517890477

- MurataGHGorbyMSChickTWHalperinAKTreatment of decompensated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the emergency department – correlation between clinical features and prognosisAnn Emerg Med19912021251291996791

- PatilSPKrishnanJALechtzinNDietteGBIn-hospital mortality following acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Intern Med2003163101180118612767954

- Ai-PingCLeeKHLimTKIn-hospital and 5-year mortality of patients treated in the ICU for acute exacerbation of COPD: a retrospective studyChest2005128251852416100133

- LindenauerPKPekowPGaoSCrawfordASGutierrezBBenjaminEMQuality of care for patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Intern Med20061441289490316785478

- YipNHYuenGLazarEJAnalysis of hospitalizations for COPD exacerbation: opportunities for improving careCOPD201072859220397808

- WedzichaJASeemungalTACOPD exacerbations: defining their cause and preventionLancet2007370958978679617765528

- MurphyTFBrauerALEschbergerKPseudomonas aeruginosa in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008177885386018202344

- BonhoefferJBarGRiffelmannMSolerMHeiningerUThe role of Bordetella infections in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitisInfection2005331131715750754

- SchneiderDGanesanSComstockATIncreased cytokine response of rhinovirus-infected airway epithelial cells in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010182333234020395558

- DonaldsonGCHurstJRSmithCJHubbardRBWedzichaJAIncreased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke following exacerbation of COPDChest201013751091109720022970

- BhowmikASeemungalTASapsfordRJWedzichaJARelation of sputum inflammatory markers to symptoms and lung function changes in COPD exacerbationsThorax200055211412010639527

- DonaldsonGCSeemungalTAPatelISAirway and systemic inflammation and decline in lung function in patients with COPDChest200512841995200416236847

- SpruitMAGosselinkRTroostersTMuscle force during an acute exacerbation in hospitalised patients with COPD and its relationship with CXCL8 and IGF-IThorax200358975275612947130

- HolguinFFolchEReddSCManninoDMComorbidity and mortality in COPD-related hospitalizations in the United States, 1979 to 2001Chest200512842005201116236848

- LangsetmoLPlattRWErnstPBourbeauJUnderreporting exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a longitudinal cohortAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008177439640118048806

- MarinJMCarrizoSJCasanovaCPrediction of risk of COPD exacerbations by the BODE indexRespir Med2009103337337819013781

- JonesRCDonaldsonGCChavannesNHDerivation and validation of a composite index of severity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the DOSE IndexAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009180121189119519797160

- LeidyNKWilcoxTKJonesPWRobertsLPowersJHSethiSStandardizing measurement of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: reliability and validity of a patient-reported diaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011183332332920813886

- StolzDChrist-CrainMBingisserRAntibiotic treatment of exacerbations of COPD: a randomized, controlled trial comparing procalcitonin-guidance with standard therapyChest2007131191917218551

- LacomaAPratCAndreoFValue of procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, and neopterin in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2011615716921468168

- BazeghiNGerdsTABudtz-JorgensenEHoveJVestboJExhaled nitric oxide measure using multiple flows in clinically relevant subgroups of COPDRespir Med201110591338134421530214

- AnthonisenNRManfredaJWarrenCPHershfieldESHardingGKNelsonNAAntibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAnn Intern Med198710621962043492164

- CelliBRMacNeeWStandards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paperEur Respir J200423693294615219010

- KestenSCelliBDecramerMLeimerITashkinDTiotropium HandiHaler in the treatment of COPD: a safety reviewInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2009439740920037679

- SethiSMurphyTFInfection in the pathogenesis and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2008359222355236519038881

- RoedeBMBresserPBindelsPJAntibiotic treatment is associated with reduced risk of a subsequent exacerbation in obstructive lung disease: an historical population based cohort studyThorax2008631196897318682520

- El MoussaouiRRoedeBMSpeelmanPBresserPPrinsJMBossuytPMShort-course antibiotic treatment in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and COPD: a meta-analysis of double-blind studiesThorax200863541542218234905

- DimopoulosGSiemposIIKorbilaIPMantaKGFalagasMEComparison of first-line with second-line antibiotics for acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: a metaanalysis of randomized controlled trialsChest2007132244745517573508

- DanielsJMSnijdersDde GraaffCSVlaspolderFJansenHMBoersmaWGAntibiotics in addition to systemic corticosteroids for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010181215015719875685

- RabeKFHurdSAnzuetoAGlobal strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summaryAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007176653255517507545

- MehtaSHillNSNoninvasive ventilationAm J Respir Crit Care Med2001163254057711179136

- AuDHBrysonCLChienJWThe effects of smoking cessation on the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbationsJ Gen Intern Med200924445746319194768

- NicholKLBakenLNelsonARelation between influenza vaccination and outpatient visits, hospitalization, and mortality in elderly persons with chronic lung diseaseAnn Intern Med1999130539740310068413

- Advisory Committee on Immunization PracticesRecommended adult immunization schedule: United States, 2011Ann Intern Med2011154316817321282696

- KretsingerKBroderKRCorteseMMPreventing tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis among adults: use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and recommendation of ACIP, supported by the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC), for use of Tdap among health-care personnelMMWR Recomm Rep200655RR-17137

- SeemungalTAWilkinsonTMHurstJRPereraWRSapsfordRJWedzichaJALong-term erythromycin therapy is associated with decreased chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbationsAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008178111139114718723437

- AlbertRKBaileyWCCasaburiRChronic azithromycin decreases the frequency of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbationsAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011183A6416

- TashkinDPCelliBSennSA 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2008359151543155418836213

- CalverleyPMAndersonJACelliBSalmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med2007356877578917314337

- NiewoehnerDERiceKCoteCPrevention of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with tiotropium, a once-daily inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator: a randomized trialAnn Intern Med2005143531732616144890

- FergusonGTAnzuetoAFeiREmmettAKnobilKKalbergCEffect of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol (250/50 microg) or salmeterol (50 microg) on COPD exacerbationsRespir Med200810281099110818614347

- WedzichaJACalverleyPMSeemungalTAHaganGAnsariZStockleyRAThe prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations by salmeterol/fluticasone propionate or tiotropium bromideAm J Respir Crit Care Med20081771192617916806

- VogelmeierCHedererBGlaabTTiotropium versus salmeterol for the prevention of exacerbations of COPDN Engl J Med2011364121093110321428765

- TashkinDPRennardSIMartinPEfficacy and safety of budesonide and formoterol in one pressurized metered-dose inhaler in patients with moderate to very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results of a 6-month randomized clinical trialDrugs200868141975200018778120

- RennardSITashkinDPMcElhattanJEfficacy and tolerability of budesonide/formoterol in one hydrofluoroalkane pressurized metered-dose inhaler in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from a 1-year randomized controlled clinical trialDrugs200969554956519368417

- WelteTMiravitllesMHernandezPEfficacy and tolerability of budesonide/formoterol added to tiotropium in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2009180874175019644045

- Prescribing information for Daliresp™ (roflumilast) tablets: initial US approval2011 Available from: http://www.frx.com/pi/Daliresp_pi.pdfAccessed March 7, 2011

- BourbeauJBartlettSJPatient adherence in COPDThorax200863983183818728206

- RestrepoRDAlvarezMTWittnebelLDMedication adherence issues in patients treated for COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20083337138418990964

- BarrRGCelliBRManninoDMComorbidities, patient knowledge, and disease management in a national sample of patients with COPDAm J Med2009122434835519332230

- SarcIJericTZiherlKAdherence to treatment guidelines and long-term survival in hospitalized patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Eval Clin Pract Epub 2011 Jan 11

- FinkJHodderRAdherence and inhaler devices in COPDRespir Ther201162833

- Riario-SforzaGGYacoubMRIncorvaiaCPulmonary rehabilitation as evaluated by clinical trials: an overviewRev Recent Clin Trials201052768420201797

- PuhanMAScharplatzMTroostersTSteurerJRespiratory rehabilitation after acute exacerbation of COPD may reduce risk for readmission and mortality – a systematic reviewRespir Res200565415943867

- AmbrosinoNFoglioKBalzanoGPaggiaroPLLessiPKestenSTiotropium and exercise training in COPD patients: effects on dyspnea and exercise toleranceInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20083477178019281092

- ManWDPolkeyMIDonaldsonNGrayBJMoxhamJCommunity pulmonary rehabilitation after hospitalisation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: randomised controlled studyBMJ20043297476120915504763

- RaskinJSpieglerPMcCuskerCThe effect of pulmonary rehabilitation on healthcare utilization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The Northeast Pulmonary Rehabilitation ConsortiumJ Cardiopulm Rehabil200626423123616926687

- ChatilaWMThomashowBMMinaiOACrinerGJMakeBJComorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseProc Am Thorac Soc20085454955518453370

- KinnunenTSaynajakangasOTuuponenTKeistinenTImpact of comorbidities on the duration of COPD patients’ hospital episodesRespir Med200397214314612587964

- AnthonisenNRConnettJEEnrightPLManfredaJHospitalizations and mortality in the Lung Health StudyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2002166333333912153966

- CalverleyPMSanchez-TorilFMcIvorATeichmannPBredenbroekerDFabbriLMEffect of 1-year treatment with roflumilast in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007176215416117463412

- DicksteinKCohen-SolalAFilippatosGESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM)Eur J Heart Fail2008101093398918826876

- van GestelYRHoeksSESinDDImpact of cardioselective beta-blockers on mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and atherosclerosisAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008178769570018565952

- RuttenFHZuithoffNPHakEGrobbeeDEHoesAWBeta-blockers may reduce mortality and risk of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseArch Intern Med20101701088088720498416

- Canadian Thoracic SocietyCOPD action plan2008 [updated 2008 Oct 20]. Available from: http://www.lung.ca/pdf/1408_THOR_ActionPlan_v3.pdfAccessed August 26, 2011

- EffingTMonninkhofEMvan der ValkPDSelf-management education for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseCochrane Database Syst Rev20074CD00299017943778

- Wood-BakerRMcGloneSVennAWaltersEHWritten action plans in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease increase appropriate treatment for acute exacerbationsRespirology200611561962616916336

- SedenoMFNaultDHamdDHBourbeauJA self-management education program including an action plan for acute COPD exacerbationsCOPD20096535235819863364

- HurstJRFitzgerald-KhanFQuintJKUse and utility of a 24-hour telephone support service for ‘high risk’ patients with COPDPrim Care Respir J201019326026520571731

- NaunheimKSWoodDEMohsenifarZLong-term follow-up of patients receiving lung-volume-reduction surgery versus medical therapy for severe emphysema by the National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research GroupAnn Thorac Surg200682243144316888872

- WashkoGRFanVSRamseySDThe effect of lung volume reduction surgery on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbationsAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008177216416917962632