Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to examine differences in alcohol consumption and its consequences when consumed alone and when mixed with energy drinks.

Methods

A survey was conducted among Dutch students at Utrecht University and the College of Utrecht. We collected data on alcohol consumption and alcohol-related consequences of alcohol consumed alone and/or alcohol mixed with energy drinks (AMED). The data were analyzed using a retrospective within-subject design, comparing occasions when subjects consumed AMED with those when they consumed alcohol only in the past 30 days.

Results

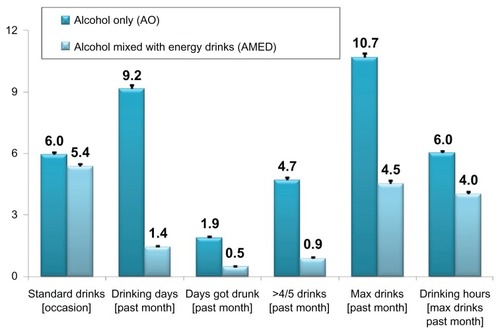

A representative sample of 6002 students completed the survey, including 1239 who consumed AMED. Compared with consuming alcohol only, when consuming AMED, students consumed significantly fewer alcoholic drinks on an average drinking day (6.0 versus 5.4, respectively), and reported significantly fewer drinking days in the previous month (9.2 versus 1.4), significantly fewer days being drunk (1.9 versus 0.5), and significantly fewer occasions of consuming more than four (female)/five (male) alcoholic drinks (4.7 versus 0.9). The maximum number of mixed alcoholic drinks (4.5) in the previous month was significantly lower when compared with occasions when they consumed alcohol only (10.7). Accordingly, the mean duration of a drinking session was significantly shorter when mixing alcoholic drinks (4.0 versus 6.0 hours). Finally, when consuming AMED, significantly fewer alcohol-related consequences were reported (2.6) for the previous year, including driving a car while intoxicated, taking foolish risks, or being injured or hurt, as compared with alcohol-related consequences when consuming alcohol only (4.9).

Conclusion

Mixing alcohol with energy drinks decreases overall alcohol consumption, and decreases the likelihood of experiencing negative alcohol-related consequences.

Introduction

Alcohol abuse is a major problem worldwide. It has been estimated that 42% of males and 20% of females in the US will experience an alcohol use disorder (abuse or dependence) during their lifetime, and approximately 12.5% of males and 5% of females meet the criteria for an alcohol use disorder in the previous year.Citation1 Excessive alcohol consumption is ranked as the third leading cause of death in the US, and is also associated with marked functional impairment.Citation1–Citation3 According to the World Health Organization, 6.2% of all deaths worldwide are related to alcohol consumption, which makes it one of the leading causes of death.Citation4 There is global concern about drinking trends among young people, particularly with regard to heavy episodic or “binge” drinking.Citation5 For example, in the US, about 500,000 college students are injured every year due to drinking alcohol, with about 1700 of them dying annually due to extreme binge-drinking.Citation6 During adolescence, several neural systems undergo alterations, and during maturation, some of these systems modulate sensitivity to a variety of the effects of alcohol, potentially increasing the propensity for relatively high levels of adolescent alcohol use. This might set the stage for later alcohol use disorders.Citation7 Hence, it is important to study factors that may contribute to increased alcohol consumption among young adults.

Concerns have been raised regarding the potential negative consequences of consumption of alcohol mixed with energy drinks (AMED). The relevant ingredient in this context is caffeine, of which most popular energy drinks contain 80 mg per 250 mL or 8.4 fl oz.Citation8,Citation9 The stimulant effect of caffeine is thought to counteract the sedative effect of alcohol, possibly leading to increased alcohol consumption and experiencing of more negative alcohol-related consequences. Only a few studies have investigated whether use of AMED is indeed associated with more alcohol consumption. O’Brien et al questioned 4271 college students, of whom 52% had consumed alcohol without mixing with energy drinks and 16.3% (N = 697) had consumed AMED in the previous 30 days, and concluded the AMED consumers to be at increased risk for alcohol-related consequences, even when adjusted for the amount of alcohol consumed.Citation10 This conclusion was based on a between-subjects comparison of AMED consumers and alcohol-only consumers. A similar design was used by Arria et al, comparing college students who consumed energy drinks versus those who did not consume energy drinks in a 3-year longitudinal study. It was concluded that consumers of energy drinks tend to have a greater involvement in alcohol and drug use and have higher levels of sensation-seeking, compared with students who do not consume energy drinks.Citation11 Other surveys reported similar significant correlations between energy drink and alcohol consumption, and reported that those who consume AMED generally consume more alcohol and experience more alcohol-related consequences than those who consume alcohol alone.Citation12–Citation15

These conclusions have raised concerns regarding AMED consumption. However, some researchers have questioned the methodology of these surveys and the interpretation of the results regarding designs used to research AMED consumption,Citation8,Citation16,Citation17 and two studies did not find comparable results while using a between-groups design.Citation18,Citation19 Penning et al reported that those who consume AMED do not consume more alcohol than those who consume alcohol only. Rossheim and Thombs found no significant relationship between AMED consumption and the chances of being intoxicated (ie, having a blood alcohol content > 0.08%). However, the main reason for criticism of existing surveys is that the majority of them have compared AMED consumers with those who consume alcohol only, using a between-groups design. Unfortunately, by comparing an AMED group with an alcohol-only group, it is not possible to determine if there is any causal relationship between energy drink consumption and overall alcohol consumption. In other words, it cannot be established from a between-group comparison whether mixing alcohol with energy drinks had any influence on overall alcohol consumption. Also, between-group analyses introduce the influence of potential confounders, such as differences between groups regarding personality characteristics. To verify whether mixing alcohol with energy drinks increases overall alcohol consumption, studies using a within-subject design are needed. A within-subject comparison is essential to determine whether AMED groups consume more alcohol on occasions when they consume AMED compared with occasions when they consume alcohol only. Another important advantage of a within-subject design is that if a sufficient sample size is obtained, the actual response rate to the survey is of minor concern. As long as the sample that completed the survey reflects the basic demographics and characteristics of the general population, a large enough sample size with adequate power for the statistical analyses is sufficient to yield reliable research results. Nevertheless, it remains important to compare the demographic characteristics of the sample with those of the total population to ensure that the sample studied is representative of this population.

Two studies have reported the results of a within-subject comparison.Citation20,Citation21 Price et al found that AMED consumption was associated with increased alcohol consumption, but their sample size of 10 subjects was too small to draw conclusions. A second within-subject comparison was presented by Woolsey et al. These authors only drew conclusions based on their between-group comparison (AMED versus alcohol-only groups), but together with the within-subject comparison (ie, within the AMED group) presented, important results were revealed, supporting the hypotheses that AMED and alcohol-only groups differ from each other in critical characteristics (eg, alcohol consumption when not mixing with energy drinks), and that within the AMED group, mixing alcohol with energy drinks does not increase overall alcohol consumption when compared with occasions on which they consume alcohol only. Woolsey et al found that when mixing energy drinks with alcohol, AMED consumers drink significantly less alcohol than on occasions when they consume alcohol only (6.28 drinks versus 8.60 drinks, respectively). Because the within-subject comparison by Woolsey et al was performed in a relatively small sample of AMED consumers (n = 150), surveys with a larger sample size are needed to confirm these findings. Given the limitations of previous survey research on mixing energy drinks with alcohol, an extensive online survey was developed and conducted in The Netherlands. The aim of this survey was to examine alcohol consumption and its consequences when consumed alone or when mixed with energy drinks using a within-subject design. Given the current scientific evidence available, it was hypothesized that there is no difference in total alcohol consumption (frequency and quantity) and alcohol-related negative consequences when alcohol is consumed alone or when mixed with energy drinks.

Materials and methods

Sample

All 70,000 students from the Utrecht University and the College of Utrecht were invited by email to complete an online survey on consumption of energy drinks and alcohol. Two teams approached students at the campuses, and distributed leaflets to remind them to complete the survey. The study protocol was reviewed by the Twente medical ethics committee, but no formal medical ethics approval needed to be obtained. Participation was anonymous and voluntary, and a prize draw was held among those who completed the survey. In total, 7158 students opened the link to the survey. After cleaning the data set the final dataset comprised 6002 students. For the analyses in this paper, data were used for the alcohol-only group (ie, those who only consumed alcohol, n = 3185), and the AMED-group (consisting of participants who consumed both alcohol only and AMED, n = 1239). Data concerning the group that consume both alcohol and energy drinks but never mix these and the group that do not consume alcohol will be discussed elsewhere.

Survey outline

After obtaining demographic data from the participants, questions were asked about alcohol use when consumed alone and when mixed with energy drinks. The consumption questions were standard ones investigating the subject’s consumption habits (frequency and quantity) considering the particular drink asked about, with a focus on the past 30 days, and adapted from the Quick Drinking Screen, which contains four consumption questions that have been shown to be highly reliable and consistent when compared with the 12-month Timeline Follow Back method.Citation22,Citation23 Mixing was defined as consuming energy drinks within a time frame of 2 hours before or after drinking alcohol.

The Dutch version of the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (BYAACQ) was included to study alcohol-related negative consequences.Citation24 The BYAACQ consists of 24 possible consequences of alcohol consumption that can be answered by “yes” or “no”. The outcome score ranges from 0 to 24. The BYAACQ was completed for alcohol only and for mixing with energy drinks depending on the specific drinking behavior of the participant. In addition to the BYAACQ, two additional items were included to determine whether participants were injured or got into a fight after alcohol consumption (with or without mixing with energy drinks). A detailed description of the survey design and its questions can be found elsewhere.Citation25 Furthermore, it should be taken into account that alcoholic drinks in The Netherlands, when obtained in a bar, pub, or restaurant, contain a standardized amount of alcohol.

Data collection and statistical analyses

The survey went online on June 6, 2011 and remained online for 10 days. Data were collected online via SurveyMonkey and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 18 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). The mean, standard deviation, and frequency distribution was computed for alcohol consumption questions and BYAACQ scores for occasions on which subjects consumed AMED or alcohol only. Variables with a normal distribution were tested with the Student t-test. For nominal variables, a χ2-test was performed. To analyze within-subject differences within the AMED group (drinking AMED versus drinking alcohol only), a paired t-test was used for consumption questions, and intraclass correlations were calculated to look for interindividual correlations where appropriate. For the BYAACQ data, a McNemar test was performed on the single items, and a paired t-test and intraclass correlation on the BYAACQ total scores. All tests were two-tailed, and differences were regarded as significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Between-group comparisons

The demographics of the participants are summarized in . The age and gender distribution of the sample obtained did not differ significantly from the total Utrecht student population.Citation25 The alcohol-only group comprised 3185 subjects and the AMED group comprised 1239 subjects. Between-group analyses showed that the groups differed significantly from each other on variables related to alcohol-only consumption, smoking, and drug use, as summarized in and . Between-group analyses also revealed a consistent pattern of significant differences on most variables, in that AMED consumption was greater than alcohol-only consumption, as summarized in .

Table 1 Demographics of study participants

Table 2 Between-group comparison of those who consumed alcohol only and those who mixed alcohol with energy drinks with regard to their alcohol consumption on occasions when they consume alcohol only (without mixing with energy drinks)

Within-subject analyses for AMED group

To establish whether mixing energy drinks with alcohol has an impact on total alcohol consumption, within-subject comparisons were performed for members of the AMED group (n = 1239), comparing occasions on which they consumed AMED with occasions on which they consumed alcohol only. The results of these comparisons are summarized in . Intraclass correlations were calculated when appropriate to examine these within-subject comparisons further.

Figure 1 Means (SEM) for within-subjects analyses in the AMED group (n = 1189) on consumption questions for alcohol only and alcohol mixed with energy drinks.

Abbreviations: AMED, alcohol mixed with energy drinks; SEM, standard errors of the mean.

The within-subject analyses revealed generally lower consumption of alcohol when combining alcohol with energy drinks. Compared with consuming alcohol only, when consuming AMED, students consumed significantly fewer alcoholic drinks (mean 6.0 ± 3.9 versus 5.4 ± 3.7, respectively; intraclass correlation 0.636, P ≤ 0.001) during an average drinking session, and reported significantly fewer drinking days in the previous month (9.2 ± 6.4 versus 1.4 ± 1.8), significantly fewer days being drunk (1.9 ± 2.7 versus 0.5 ± 1.0), and significantly fewer occasions of consuming more than four (female)/five (male) alcoholic drinks (4.7 ± 4.7 versus 0.9 ± 1.7). Furthermore, compared with consuming alcohol only, when consuming AMED, students consumed significantly fewer maximum number of alcoholic drinks on a single occasion in the previous month (10.7 ± 6.8 versus 4.5 ± 5.7, respectively; intraclass correlation 0.185, P ≤ 0.001). Accordingly, duration of alcohol consumption on this occasion was significantly shorter when consuming AMED than when consuming alcohol only (4.0 ± 3.3 versus 6.0 ± 3.0 hours, respectively; intraclass correlation 0.301, P ≤ 0.001). All differences between consuming AMED and alcohol only were examined using a paired t-test and are significant at the P < 0.001 level. Finally, the highest number of AMED consumptions on one occasion during the previous year was 4.8 ± 4.8.

BYAACQ

Confirmation of alcohol-related consequences after consuming AMED or alcohol only are summarized in . The within-subject comparisons show that when consuming AMED alcohol-related negative consequences are often experienced significantly less when compared with consuming alcohol only. The total BYAACQ score shows a reduction of 47% from 4.9 ± 3.8 for drinking alcohol only to 2.6 ± 3.5 for AMED (intraclass correlation 0.414, P ≤ 0.001). For two items (numbers 18 and 22) no significant difference was found between the AMED and alcohol only occasions. None of the individual items showed an increased chance of experiencing an alcohol-related negative consequence on AMED occasions compared with drinking alcohol only.

Table 3 Within-subjects comparison in the AMED group (N = 1110) on BYAACQ items for occasions on which they consumed alcohol only compared with occasions on which they mixed alcohol with energy drinks

Discussion

The results of this survey show that people who mix alcohol with energy drinks do not consume more alcohol when they consume AMED compared with occasions on which they consume alcohol only. In contrast, when consuming AMED, students reported consuming significantly fewer alcoholic drinks on average, having fewer drinking days in the past month, less days of being drunk in the past month, and fewer occasions of consuming more than 4–5 drinks in the past month, compared with consuming alcohol only. Further, when consuming AMED, the maximum number of alcoholic drinks on one occasion during the past month was significantly lower when compared with occasions on which only alcohol was consumed. In addition, no increase in alcohol-related consequences was reported for occasions when they consumed AMED; this finding is of importance, considering that some authors have suggested otherwise.Citation10–Citation12,Citation14 The current study shows clearly that mixing alcohol with energy drinks does not increase the likelihood of potentially dangerous activities or serious negative consequences, such as driving while intoxicated, being injured, or getting involved in a fight, unplanned sexual activity, or taking foolish risks. The within-subject analyses yield results that are comparable with those reported by Woolsey et al,Citation20 and our current results also clearly show that mixing alcohol with energy drinks does not increase overall alcohol consumption, nor the likelihood of experiencing negative consequences. The large sample size and robust findings of the current study are supportive of this conclusion.

The fact that mixing alcohol with energy drinks has no negative impact on overall alcohol consumption or its negative consequences should not be interpreted as suggesting that alcohol abuse does not exist among Dutch students. The data clearly show that alcohol consumption exceeds levels of consumption that are generally accepted as safe, and the majority of students engaged in binge drinking, especially on days when they did not consume AMED (see ).

Therefore, there is still a lot of work to do in preventing excessive alcohol consumption amongst Dutch students. From our data, it is apparent that focusing specifically on AMED consumption is not warranted. The significance of the study results lies in the fact that this is the first large-scale survey using appropriate methodology (ie, a within-subject design) to determine whether mixing alcohol with energy drinks has an effect on overall alcohol consumption when compared with consuming alcohol only. This information cannot be obtained reliably from between-group comparisons. It can be argued that recall bias may interfere with obtaining reliable survey data. However, when applying a within-subject design, there is no reason to assume that participants will recall consumption characteristics differently between AMED or alcohol-only occasions. To avoid the possibility of recall bias entirely, a prospective study design may be a solution, but it would be expensive and time-consuming to achieve a sample size as large as that in the current survey.

Interestingly, when applying a between-groups design, as used by other researchers to compare alcohol-only and AMED groups for demographics and alcohol-only consumption patterns, the groups differed from each other on variables concerning alcohol-only consumption and its consequences, drug use and smoking, following a standard pattern of AMED > alcohol only. This observed pattern could be caused by underlying personality characteristics that might differ between the groups, for instance levels of risk-taking behavior. The same authors that claim increased alcohol consumption caused by energy drinks based on such a between-groups design also report that AMED consumers have higher scores on (impulsive) sensation-seeking and childhood conduct problems.Citation11,Citation12 Moreover, having a sports-related identity is associated with frequency of energy drink consumption, mediated by masculine norms and level of risk-taking behavior.Citation11,Citation12,Citation26 Increased levels of risk-taking behavior may be reflected by a generally disinhibited behavioral pattern for an individual. The findings of the current study and othersCitation11,Citation12,Citation26 confirm that individuals who consume more alcohol also use more drugs.Citation27 Taken together the focus of research should not be on AMED consumption but on persons who are involved in heavy alcohol consumption per se. Future research is needed to explore the possibility that this specific group of alcohol consumers have different personality characteristics, ie, higher risk-taking, underlying their pattern of increased substance use.

The reduction in alcohol consumption reported for the AMED group when mixing alcohol with energy drinks as compared with drinking alcohol only was not expected. It was hypothesized that there would be no difference and we have no clear explanation for this observed decrease in alcohol consumption. When looking at the ingredients of energy drinks, it could be speculated that taurine (a nonessential amino acid and an ingredient of most energy drinks) may have an effect on alcohol consumption, given that a modest reduction of voluntary ethanol consumption induced by taurine has been found in rats.Citation28 Other ingredients in energy drinks are unlikely to play a role. However, the low intraclass correlations with a maximum of 0.6 suggest interindividual differences, indicating that factors other than coconsumption of energy drinks may explain the observed decrease in alcohol consumption. A possible reason for decreased overall alcohol consumption may be that spirits and energy drinks are generally more expensive than beer and wine. Wagenaar et al showed that the price of alcohol beverages is inversely related to the quantity of alcohol consumed.Citation29 However, it is unknown if and how much students had to pay for their alcoholic and energy drinks on the occasions they reported in our survey, or whether they were consumed at home or in a bar.

Our data show that the maximum number of drinks consumed when drinking alcohol only (10.7) was much higher than last month’s maximum number of alcoholic drinks on AMED occasions (4.5). In fact, the maximum number of alcoholic drinks on AMED occasions equals that of the 4–5 rule, whereas this is doubled for the maximum monthly consumption of alcohol only (when not mixing). Therefore, it is understandable that negative consequences are experienced more commonly when people do not mix alcohol with energy drinks. It is likely that alcohol-related consequences occur most often on heavy drinking days and less often on days during which few alcoholic drinks are consumed. Although we have information on the number of drinking days, it would not be correct to use this information as a covariate in statistical analysis. The main reason for this is that it is unknown how many of the total drinking days were heavy drinking days (ie, close to the maximum monthly number of drinks) and how many were “normal” drinking days (ie, without experiencing negative consequences). Although there are data on the number of days spent intoxicated and the number of days on which more than 4–5 alcoholic drinks were consumed, including these values in the statistical analysis would result in speculative interpretation of the data, because it can only be guessed if and how many negative consequences subjects experienced on each of these days. The most firm conclusion supported by our data is that people consume less alcohol when they mix alcohol with energy drinks, both on average drinking days and on their maximum heavy drinking occasions. It is understandable that fewer negative consequences are experienced when alcohol consumption is reduced by mixing it with energy drinks.

Our analysis shows that the student sample obtained does not differ significantly from the total Utrecht student population.Citation25 Also, there is no reason to assume that students from Utrecht University are very different from those attending other universities in The Netherlands. Nevertheless, a limitation of this survey is that it was conducted only in The Netherlands, which may limit the generalizability of its results to other countries. Therefore, this study will be replicated in other parts of the world, including Australia and the US. These surveys will also adopt a within-subject design and include a sufficient number of participants in the AMED group to ensure adequate statistical power in order to have confidence in the results. Furthermore, any underlying personality characteristics likely to cause differences in alcohol-only consumption per se need to be examined in greater detail. In conclusion, the results of this survey show that mixing alcohol with energy drinks decreases overall alcohol consumption, and decreases the likelihood of experiencing negative alcohol-related consequences.

Disclosure

This survey was supported by a grant from Red Bull GmbH. Red Bull GmbH was not involved in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, interpretation of the data, or preparation of the manuscript. JV has received research support from Takeda Pharmaceuticals and Red Bull GmbH, and has been a scientific advisor for Takeda, Sanofi-Aventis, Transcept, Sepracor, Red Bull GmbH, Deenox, Trimbos Institute, and CBD. BO is a scientific advisor for Emotional Brain BV and has received research support from Emotional Brain, PsychoGenics Inc, Sepracor, Servier, Abbott, and the Dutch Brain Research Organization. The other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- HasinDSStinsonFSOgburnEGrantBFPrevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related ConditionsArch Gen Psychiatry20076483084217606817

- MokdadAHMarksJSStroupDFGerberdingJLActual causes of death in the United States, 2000JAMA20042911238124515010446

- Young-WolffKCEnochMAPrescottCAThe influence of gene-environment interactions on alcohol consumption and alcohol use disorders: a comprehensive reviewClin Psychol Rev20113180081621530476

- World Health OrganizationGlobal Status Report on Alcohol and HealthGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2011

- McCambridgeJMcAlaneyJRoweRAdult consequences of late adolescent alcohol consumption: a systematic review of cohort studiesPLoS Med20118e100041321346802

- HingsonRWZhaWWeitzmanERMagnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among US college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005J Stud Alcohol Drugs2009Suppl 161220

- SpearLPAdolescent neurobehavioral characteristics, alcohol sensitivities, and intake: setting the stage for alcohol use disorders?Child Dev Perspect2011523123822328900

- VersterJCAufrichtCAlfordCEnergy drinks mixed with alcohol: misconceptions, myths, and factsInt J Gen Med2012518719822399863

- ReissigCJStrainECGriffithsRRCaffeinated energy drinks – a growing problemDrug Alcohol Depend20099911018809264

- O’BrienMCMcCoyTPRhodesSDWagonerAWolfsonMCaffeinated cocktails: energy drink consumption, high-risk drinking, and alcohol-related consequences among college studentsAcad Emerg Med20081545346018439201

- ArriaAMCaldeiraKMKasperskiSJIncreased alcohol consumption, nonmedical prescription drug use, and illicit drug use are associated with energy drink consumption among college studentsJ Addict Med20104748020729975

- ArriaAMCaldeiraKMKasperskiSJVincentKBGriffithsRRO’GradyKEEnergy drink consumption and increased risk for alcohol dependenceAlcohol Clin Exp Res20113536537521073486

- MillerKEEnergy drinks, race, and problem behaviors among college studentsJ Adolesc Health20084349049718848678

- ThombsDLO’MaraRJTsukamotoMEvent-level analyses of energy drink consumption and alcohol intoxication in bar patronsAddict Behav20103532533019954894

- BergerLKFendrichMChenHYArriaAMCislerRASociodemographic correlates of energy drink consumption with and without alcohol: results of a community surveyAddict Behav20103651651921276661

- VersterJCAlfordCUnjustified concerns about energy drinksCurr Drug Abuse Rev201141321466503

- SkeenMPGlennLLImaginary link between alcoholism and energy drinksAlcohol Clin Exp Res2011351375137621651587

- PenningRde HaanLVersterJCCaffeinated drinks, alcohol consumption, and hangover severityOpen Neuropsychopharmacol J201143639

- RossheimMEThombsDLArtificial sweeteners, caffeine, and alcohol intoxication in bar patronsAlcohol Clin Exp Res2011351891189621554335

- WoolseyCWaigandtABeckNCAthletes and energy drinks: reported risk-taking and consequences from the combined use of alcohol and energy drinksJ Appl Sport Psychol2010226571

- PriceSRHilcheyCADarredeauCFultonHGBarrettSPEnergy drink co-administration is associated with increased reported alcohol ingestionDrug Alcohol Rev20102933133320565526

- RoyMDumMSobellLCComparison of the quick drinking screen and the alcohol timeline followback with outpatient alcohol abusersSubst Use Misuse2008432116212318825590

- SobellLCAgrawalSSobellMBComparison of a quick drinking screen with the timeline followback for individuals with alcohol problemsJ Stud Alcohol Drugs200364858861

- VersterJCHerwijnenJOlivierBKahlerCWValidation of the Dutch version of the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (B-YAACQ)Addict Behav20093441141417942242

- de HaanLde HaanHOlivierBVersterJAlcohol mixed with energy drinks: methodology and design of the Utrecht Student SurveyInt J Gen Med2012588989823118547

- MillerKEWired: energy drinks, jock identity, masculine norms, and risk takingJ Am Coll Health20085648149018400659

- de HaanLKuipersEKuertenYvan LaarMOlivierBVersterJCThe RT-18: a new screening tool to assess young adult risk-taking behaviorInt J Gen Med2011457558421887111

- OliveMInteractions between taurine and ethanol in the central nervous systemAmino Acids20022334535712436202

- WagenaarACSaloisMJKomroKAEffects of beverage alcohol price and tax levels on drinking: a meta-analysis of 1003 estimates from 112 studiesAddiction200910417919019149811