Abstract

Background

Musculoskeletal joint pain of varied etiology can be diagnosed and treated with joint and soft-tissue corticosteroid injections.

Purpose

The purpose of our study was to compare patients’ bodily pain and quality of life (QOL), in addition to the procedural benefit and patient satisfaction, before and after musculoskeletal injections in the office setting.

Patients and methods

Patients were eligible for recruitment if they were over age 18 and had an injection for musculoskeletal pain from a primary care provider in an office procedural practice. Included in our analysis were knee joint/bursa, trochanteric bursa, and shoulder joint/bursa injection sites. The variables measured were pain, benefit from the injection, QOL physical and mental components, and patient satisfaction. This was a retrospective cohort study approved by the institutional review board.

Results

Patients’ pain was assessed by the patients using a six-point Likert scale (none, very mild, mild, moderate, severe, and very severe). We noted that self-perception of pain decreased from 3.10 (± standard deviation at baseline 0.96) before to 2.36 (± standard deviation after the infection 1.21) (P = 0.0001) after the injection. In terms of the impact on QOL, our patients had a pre-injection physical score of 37.25 ± 8.39 and a mental score at 52.81 ± 8.98. After the injections, the physical score improved to 42.35 ± 9.07 (P = 0.0001) and the mental to 53.54 ± 8.20 (P = 0.0001) for the overall group. Ninety-six percent of the patients reported they were satisfied or extremely satisfied in the procedure clinic.

Conclusion

In this study, we found significant pain relief and improved physical QOL in patients undergoing an injection in the knee joint/bursa, shoulder joint/bursa, or trochanteric bursa by primary care providers in the office setting.

Introduction

Musculoskeletal injections are an effective treatment for joint and soft-tissue pain, due to a variety of causes. Typically, providers initially address musculoskeletal and, in particular, joint pain with oral systemic anti-inflammatory agents; however, studies have highlighted the effectiveness of local injections as monotherapy in certain settings.Citation1–Citation3 Injection therapy is performed by a variety of providers, including orthopedic surgeons, rheumatologists, physiatrists, podiatrists, and primary care physicians (family medicine, internal medicine). While studies have shed some light on the efficacy of these injectionsCitation4 and have compared variations in utilization patterns of corticosteroids and local anesthetics between different specialty and primary care providers,Citation5 it is unclear how these procedures improve patients’ quality of life (QOL) when performed by primary care physicians in a purely outpatient setting.

In addition to improving pain, patients often undergo local injection therapy as a means of improving their QOL. The use of quality as a benchmark of superior medical care is becoming increasingly important. Self-assessment is an often-used means of examining the effects of an intervention on a patient’s QOL. One such self-survey is the Short Form-8 (SF-8), which has been previously used in studies of injection therapy.Citation6,Citation7 There are a few studies from primary care practices where a patient database was used to track the effectiveness of injection-therapy procedures. However, most databases are of studies with small patient numbers or are from mainly rheumatology practices, some of which examine the utility of ultrasound-guided injections.Citation8,Citation9 To our knowledge, this is the first study of its size to examine patients’ QOL outcomes, following local injection therapy in a primary care setting, using a simple self-assessment tool such as the SF-8 as part of a provider-maintained patient database.

The primary purpose of this study was to determine if patients experienced an improvement in pain and QOL parameters after joint and soft-tissue injections. The secondary outcome of interest involved determining patient satisfaction with the procedure itself. To answer these questions, we developed and reviewed a registry of patients undergoing injections in an outpatient, primary care, multidisciplinary procedural practice, which involved physicians, registered nurses, and licensed nurse practitioners.

Material and methods

Study design

This was a retrospective cohort study of 1188 adults, over age 18, seen in Mayo Clinic’s Primary Care Internal Medicine practice, in Rochester, Minnesota. The study was approved by Mayo Clinic’s Institutional Review Board and was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.Citation10

Setting

The study was conducted in an outpatient procedural practice within the larger outpatient practice in Rochester. The decision to proceed with the injection and the injection site were determined by the patients’ primary care providers. Patients were injected by select primary care providers proficient in musculoskeletal injections who formed the outpatient procedural practice within the larger outpatient primary care practice. Patients gave their clinical consent for injection in accordance with standard clinical practice. The records of the participants were evaluated from July 2010 to June 2011. Data were collected from the same time period.

Participants

Patients were over the age of 18. Patients were eligible for recruitment if they had an injection for musculoskeletal pain in the procedural practice during the period mentioned above. In concordance with Minnesota law, participants were excluded if they did not give authorization for medical record use.

Technique

We included injections around the knee (joint and bursa), shoulder (joint and bursa), and hip (trochanteric bursa) in the analysis. The technique for most of these injections was landmark-guided appropriate for the region. Some providers aspirated joint and bursal fluid prior to injections; however, this information was not collected. All primary care physicians performing the procedures had direct-observation training experience for 6 to 8 weeks before independently performing the procedures. One provider with ultrasound training did selected procedures around the knee and shoulder by utilizing ultrasound guidance.

Variables

There were four primary outcome variables: pain, benefit from the injection, QOL, and patient satisfaction. We measured the mean pain scores before and after injection. In addition, we obtained and compared dichotomized pain data (significant pain – severe or very severe, versus no significant pain – none to moderate) before and after injection.

Patients’ QOL was measured using the SF-8, a validated measure of QOL. The SF-8 QOL survey consists of physical and mental QOL measures. Each component is scored from 0 to 100, with higher scores reflecting a better QOL. All of the information was obtained through patient-completed pre-injection surveys in the office, prior to the procedure, and by nursing-staff follow-up telephone calls, 4 weeks post-procedure. Additionally, information regarding patients’ satisfaction and perceived benefit from the injection was collected on the follow-up phone calls. Patients’ satisfaction was measured using a four-point Likert scale: extremely satisfied, satisfied, somewhat satisfied, or not satisfied. Likewise, patients’ benefit from the injection was measured using another four-point Likert scale: no benefit, very little benefit, some benefit, or a lot of benefit. All of the above data, in addition to demographic information, were recorded in a procedural clinic registry database. The primary predictor variables were age and gender, which were obtained from the electronic medical record.

Data sources and measurement

The primary data sources were the electronic medical record and the procedural clinic registry. The effectiveness of the procedures was collected as noted above.

Bias

The primary source of bias was the potential placebo response to the injection. The act of using a needle and having a specialized visit might have predisposed some participants to feel that the pain should improve after the procedure. There was also a potential for bias from the pre-injection survey, which was filled out by patients in the office, and from the post-injection information, which was collected through follow-up phone calls made by nursing staff. This was done because a majority of the patients did not need to present in person for another clinical evaluation.

Study size

All eligible participants were enrolled in the study.

Statistical methods

The demographic aspects of the cohort, using mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables or frequency (percentage) for categorical variables, were reported. The Student’s paired t-test was used to compare changes from pre- to posttesting in pain scores, and from SF-8 physical and mental scores. Pearson’s Chi-squared test was used to compare patient satisfaction with benefit from the procedure, following the injection. Any P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed by SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients

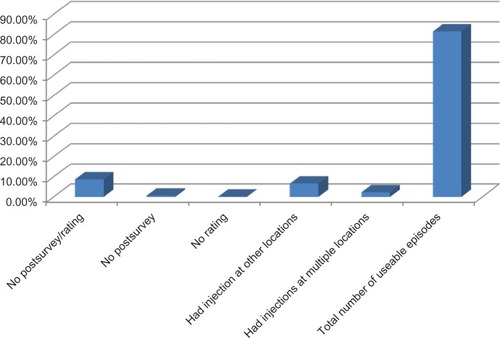

A total of 1456 records from 1188 participants were accumulated using the REDCAP database in this study from July 2010 to June 2011. All participants had authorization for participation in this research. There were 138 records with no follow-up information; therefore, they were excluded from analysis. Out of the remaining 1318 records, 97 had injections in locations other than a knee (joint and bursa), shoulder (joint and bursa), or hip (trochanteric bursa), and 33 had injections at multiple locations; hence, these records were also excluded ().

Out of 1188 records, 839 (71%) were women and 349 (29%) were men. Seventy-seven percent of the patients studied were over 60 years of age, with an average age of 68.98 (20–99). The 968 participants studied had the following individual injections: 598 on the knee, 311 on the shoulder, and 279 on the hip. Forty-five (3.78%) of the injections used ultrasound and were not subcategorized. The average Charlson comorbidity index was 1.44 (0, 14) ( and ).

Table 1 Demographics

Table 2 Disease severity

Outcomes

Overall, our patients had a pre-injection physical score of 37.25 ± 8.39 and a mental score of 52.81 ± 8.98. After the injections, the physical score improved to 42.35 ± 9.07 (P = 0.0001) and the mental to 53.54 ± 8.20 (P = 0.0001) for the overall group. Self-perception of pain also decreased from 3.10 (±0.96) to 2.36 (±1.21) (P = 0.0001). Thus, the group, as a whole, felt improvement after the procedure. By gender, men had a significant reduction in body pain scores and improvement in the physical score, but no change in the mental score. Women had improvement in the physical and mental scores, as well as reductions in body pain scores (all P values were <0.001). Subjects over age 60 had improvement in physical and mental scores and reduction in overall body pain. Those under 60 had improvements in physical scores, but not mental scores ().

Table 3 Pre- and posttesting by injection location

There were improved physical scores and reduced body pain across all three injected sites. Physical scores improved significantly for all three injection sites (knee, shoulder, and hip). Mental QOL improved with knee injections in females and those over 60 years of age; however, no change was noted for shoulder and hip injections.

Patient satisfaction with the injection was generally good overall, with 1142 patients (96%) reporting they were satisfied or extremely satisfied with the procedure clinic and 905 patients (76%) reporting some or a lot of benefit from the injection. There were no differences noted across age and gender. The perceived benefit of injections differed by joint site: the perceived benefit from knee injection was at 80% – higher than that from the shoulder injection, at 73%, and from the hip, at 70% (P = 0.014 and P = 0.0008, respectively). The variables of gender, age, and injection site all showed the same trend ().

Table 4 Patient satisfaction ratings

Discussion

In our study, we found a significant improvement in bodily pain scores 4 weeks after injections at the knee, shoulder, and the hip overall, and in all groups. The administration of a local steroid injection therapy, regardless of location or patient age, led to significant reduction in pain levels and improvement of physical QOL measures. These results support the notion that primary care physicians, well trained and experienced in the administration of local injection therapy, can reduce patients’ joint-pain levels and improve their physical QOL. Probably the most common uses for intra-articular corticosteroid injections are in the knees and shoulders of patients with degenerative joint diseases, including osteoarthritis. The benefit of local corticosteroid injections into the knee has been well studied and reported in patients with osteoarthritis.Citation11,Citation12 This study reinforces the importance of these injections in the primary care office as a viable mechanism to reduce pain in all types of patients. Our study additionally highlights the positive impact of pain reduction on the overall QOL of people undergoing injection therapy.

In our evaluations, we found a difference in mental QOL when using a subgroup analysis. Men demonstrated a greater improvement in physical QOL measures, compared to mental QOL. Gender-related differences in response to injections have been reported in previous studies.Citation13 The above finding in our study may reflect a lack of pain impact on men’s mental QOL, or it may reflect a greater pain impact on females’ mood. In the older adults, one likewise saw a greater impact of injections on mental QOL scores, compared to younger adults.

Across different injections sites, we found universal improvement in pain scores and physical QOL. It is further interesting to note that the results across the different injection sites were similar across different age groups and genders. Certain studies have shown that more than 20% of injections are, in fact, not intra-articular.Citation14,Citation15 Thus, one might expect some differences between different injection types, depending upon the ease of intra-articular or intrabursal injection. This might be explained by some reports suggesting that a precise intra-articular injection of a steroid may not be necessary for clinical benefit.Citation15,Citation16 By some reports, up to three-fourths of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee, receiving a local injection therapy, experience a significant positive response.Citation17 We found similar clinical results, with over 76% overall noting an improvement in pain. Another study reported a wide variation of success – from conservative management that included physical therapy, injections, and systemic pharmacotherapy – of 33% to 92%, in patients with shoulder pain secondary to rotator cuff tear.Citation18 Clinical and patient predictors identifying those most likely to benefit are scarce,Citation19 forming an area of much-needed research and insight.

The majority of patients, including those that reported no clinical benefit, reported being significantly satisfied by their experience with the administration of injection therapy. Thus, 96% were satisfied or extremely satisfied, despite only a 76% self-perceived benefit. This may reflect the patients’ satisfaction with the attempt to improve the pain, even though the pain was not resolved. Many patients may perceive the benefits, which include improved pain levels, mobility, ability to participate in physical therapy, and QOL measures. However, a limiting factor of injection therapy is its short-term effectiveness.Citation1,Citation20 A Cochrane review reported corticosteroid-containing joint injections to be more effective than a placebo or hyaluronic acid, with respect to pain relief, for up to 3 weeks.Citation1 However, some reports suggest that hyaluronic acid may be better for longer-term pain relief beyond 4 weeks.Citation21 The longer-term benefits of corticosteroids are questionable, and differences in outcomes between injection therapy and conservative management may not be significant.Citation22

This study had both strengths and weaknesses. First, it relied on a self-report option as opposed to anthropomorphic measurements, which may have led to recall bias or other biases. Additionally, there may be a placebo effect from the injection. In a systematic review of the Cochrane database, it was noted that for rotator cuff disease, subacromial steroid injection had a small benefit over placebo in some trials.Citation23 The QOL questionnaire and self-reported pain are standard measures, which should be reproducible in other offices and clinical settings. The providers who performed these procedures are primary care providers who devote a part of their clinical practice to procedures. Therefore, results should be generalizable to those family medicine physicians and internists who routinely perform procedures in the office; however, the results of physicians performing the procedures less frequently may differ. The population of Olmsted County, and of southeastern Minnesota in general, is largely Northern European, so the results may differ in other populations.

Conclusion

In this study of 1188 patients, we found pain relief and improved physical QOL in patients undergoing a joint injection in the knee, shoulder, or hip. This improvement did not change by age, gender, or injection site. Mental QOL improved overall, but did so specifically in women and those over 60 years of age. Knee injections similarly improved mental QOL. Localized corticosteroid injections can be successfully performed in an outpatient clinic by primary care physicians, and they can improve QOL.

Acknowledgments/disclosure

We would like to acknowledge the Primary Care Internal Medicine procedure nurses and support staff that have helped with surveys and follow-up phone calls: Christine Bray, Carol Fealey, Kristine McCoy, Jacqueline McGee, Jean Mensink, Lori Momany, and Julie Rindels. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BellamyNCampbellJRobinsonVGeeTBourneRWellsGIntraarticular corticosteroid for treatment of osteoarthritis of the kneeCochrane Database Syst Rev20062CD00532816625636

- FriedmanDMMooreMEThe efficacy of intraarticular steroids in osteoarthritis: a double-blind studyJ Rheumatol1980768508567009857

- RavaudPMoulinierLGiraudeauBEffects of joint lavage and steroid injection in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: results of a multicenter, randomized, controlled trialArthritis Rheum199942347548210088770

- SkedrosJGHuntKJPittsTCVariations in corticosteroid/anesthetic injections for painful shoulder conditions: comparisons among orthopaedic surgeons, rheumatologists, and physical medicine and primary-care physiciansBMC Musculoskelet Disord200786317617900

- BurbankKMStevensonJHCzarneckiGRDorfmanJChronic shoulder pain: part II. TreatmentAm Fam Physician200877449349718326169

- WareJKosinskiMDeweyJGandekBHow to Score and Interpret Single-item Health Status Measures: A Manual for Users of the SF-8 Health Survey2nd EdBoston, MAQualityMetric2001

- Quality MetricThe SF-8™ Health Survey. 2002 [webpage on the Internet]Medical Outcomes Trust Available from: http://www.sf-36.org/tools/sf8.shtmlAccessed October 27, 2008

- SmithMDCan a rheumatologist be a procedural specialist? The experience of an Australian rheumatologistInt J Rheumatic Dis2008112118120

- El MiedanyYMusculoskeletal US: examining the jointsBr J Nurs201221634034422584929

- GoodyearMDKrleza-JericKLemmensTThe Declaration of HelsinkiBMJ2007335762162462517901471

- ArrollBGoodyear-SmithFCorticosteroid injections for osteoarthritis of the knee: meta-analysisBMJ2004328744486915039276

- GodwinMDawesMIntra-articular steroid injections for painful knees. Systematic review with meta-analysisCan Fam Physician20045024124815000335

- LeopoldSSReddBBWarmeWJWehrlePAPettisPDShottSCorticosteroid compared with hyaluronic acid injections for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. A prospective, randomized trialJ Bone Joint Surg Am200385-A71197120312851342

- BliddalHPlacement of intra-articular injections verified by mini air-arthrographyAnn Rheum Dis1999581064164310491364

- JonesAReganMLedinghamJPattrickMManhireADohertyMImportance of placement of intra-articular steroid injectionsBMJ19933076915132913308257889

- SambrookPNChampionGDBrowneCDCorticosteroid injection for osteoarthritis of the knee: peripatellar compared to intra-articular routeClin Exp Rheumatol1989766096132692894

- GaffneyKLedinghamJPerryJDIntra-articular triamcinolone hexacetonide in knee osteoarthritis: factors influencing the clinical responseAnn Rheum Dis19955453793817794044

- LongoUGFranceschiFBertonAMaffulliNDroenaVConservative treatment and rotator cuff tear progressionMed Sport Sci201257909921986048

- JonesADohertyMIntra-articular corticosteroids are effective in osteoarthritis but there are no clinical predictors of responseAnn Rheum Dis199655118298328976640

- HepperCTHalvorsonJJDuncanSTGregoryAJDunnWRSpindlerKPThe efficacy and duration of intra-articular corticosteroid injection for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review of level I studiesJ Am Acad Orthop Surg2009171063864619794221

- BannuruRRNatovNSObadanIEPriceLLSchmidCHMcAlindonTETherapeutic trajectory of hyaluronic acid versus corticosteroids in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysisArthritis Rheum200961121704171119950318

- BrinksAvan RijnRMWillemsenSPCorticosteroid injections for greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a randomized controlled trial in primary careAnn Fam Med20119322623421555750

- BuchbinderRGreenSYoudJMCorticosteroid injections for shoulder painCochrane Database Syst Rev20031CD00401612535501