Abstract

Association of atrial septal aneurysm (ASA) with patent foramen ovale (PFO) is considered an important risk factor for cardioembolism frequently forwarding paradoxical embolism in patients with cryptogenic or unexplained cerebral ischemic events. We herein describe the case of a 69-year-old male patient reporting uncontrolled movements of the right arm due to a muscle weakness, slurred speech, and paresthesia in the oral region some seconds after he had blown his nose. These neurological symptoms had improved dramatically within a few minutes and were completely regressive at admission to our hospital about two hours later. On transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) a huge ASA associated with PFO was detected. Diagnosis of the large-sized ASA was also confirmed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Due to the early complete recovery from his neurological symptoms, the patient was diagnosed with a transient ischemic attack (TIA). After nine days he was discharged in a good clinical condition under the treatment with oral anticoagulation. It is concluded that in cryptogenic or unexplained stroke or TIA TEE should always be performed to rule out ASA and PFO as potential sources for paradoxical embolism in those inconclusive clinical situations.

Introduction

Association of atrial septal aneurysm (ASA) with patent foramen ovale (PFO) is considered an important risk factor for cardioembolism frequently forwarding paradoxical embolism in patients with cryptogenic or unexplained cerebral ischemic events.Citation1–Citation4

Case presentation

Symptoms and history

In February 2012, a 69-year-old man was referred to our emergency department. He had uncontrolled movements of the right arm not corresponding to fasciculations, but primarily due to muscle weakness, slurred speech, and paresthesia in the oral region some seconds after he had blown his nose. All neurological symptoms dramatically improved again after a few minutes and were not detectable any more at admission to our hospital about two hours later. Previous diagnoses were arterial hypertension, non insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, stenting of the left internal carotid artery, inferior wall myocardial infarction, and chronic obstructive lung disease.

Basic cardiologic findings

Further cardiologic examination showed no significant findings at heart auscultation. The 12 lead electrocardiogram (Bioset 8000, Hörmann Medizintechnik Zwönitz GmbH, Zwönitz, Germany) revealed a sinus rhythm with a normal electrical axis of the heart of 30°–60° on the frontal plane and neither repolarization disorders nor bundle branch block.

Imaging techniques

A cranial computed tomography (CT; SOMATOM Emotion 6, Siemens AG, Healthcare Sector, Erlangen, Germany) revealed no acute ischemia or hemorrhage, but an old small lacunary lesion on the left side of the cerebellum.

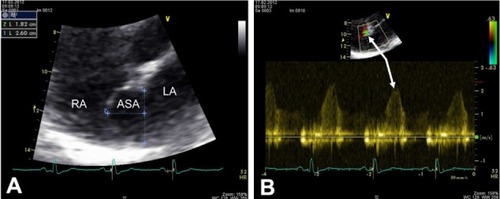

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE; Vivid 7 Dimension, GE Wingmed Ultrasound A/S, Horten, Norway), showed regular size of all four chambers, normal left ventricular ejection fraction of 60% with hypokinesia inferior and posterior due to an old myocardial infarction, and diastolic dysfunction at grade I. Minimal mitral and tricuspid regurgitation associated with a maximum transtricuspid pressure gradient of 30 mmHg were found. From the apical four-chamber view a huge atrial septal aneurysm (ASA) with a bulging into the right atrium (RA) of 18 mm and a base width of 26 mm, associated with a small left-to-right shunt as assessed by color and pulsed-wave (PW) Doppler examination (Vivid 7 Dimension, GE Wingmed Ultra sound A/S, Horten, Norway), was seen ( and ). Subsequently, a transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) was performed to confirm the association of the two anatomical abnormalities involving the interatrial septum (IAS).

Figure 1 Transthoracic echocardiogram. (A) Four-chamber view with the use of zoom function demonstrates an ASA with a pronounced protrusion into the RA of 18 mm and a base width of 26 mm. (B) Color and PW Doppler echocardiographic examination reveals a small left-to-right shunt through a small PFO (white arrows).

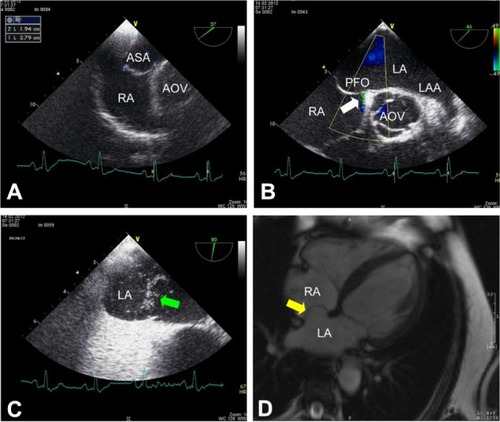

On TEE, an ASA with a prominent bulging into the RA of a size similar to that detected by TTE could be confirmed (). Moreover, a small PFO with approximately 1.5 mm of separation between septum primum and secundum characterized by spontaneous left-to-right shunt () and right-to-left shunt during Valsalva maneuver () was demonstrated. No other cardiac anatomical abnormality was found. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; MAGNETOM Avanto 1.5T, Siemens AG, Healthcare Sector, Erlangen, Germany) also revealed a huge ASA ().

Figure 2 Transesophageal echocardiogram and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). (A)Transesophageal short-axis view at 37° confirms the giant ASA with an excursion into the RA of 19 mm and a base diameter of 28 mm. (B) Transesophageal short-axis view (46°) shows a left-to-right shunt through a small PFO (white arrow) as detected by color Doppler. (C) Using agitated gelafundin (4%) intravenously some microbubbles (green arrow) can be demonstrated in LA during Valsalva maneuver indicating a right-to-left shunt through the small PFO in case of elevated intrathoracic pressure (transesophageal short-axis view at 80°). (D) Cardiac MRI (transverse plane) also reveals a huge ASA with protrusion into the RA (yellow arrow).

On color Doppler and duplex ultrasonography, a general atherosclerosis and plaques were found in the brain-supplying arteries, and a mild-to-moderate stenosis of the external carotid artery on the left side, but no in-stent restenosis of the left internal carotid artery could be detected. Furthermore, Doppler ultrasound examination of the lower extremities demonstrated no deep vein thrombosis.

Diagnosis and clinical course

Since the neurological symptoms improved dramatically within a few minutes and had completely regressed after two hours, the patient was diagnosed with a transient ischemic attack (TIA). Therefore, an intracranial MRI including an angiographic study was not performed in addition to the CT scan of the brain. The possibility of another paroxysmal neurological disease such as epilepsy was discussed and excluded by a neurological consultation. Taking into account the association of the combined occurrence of ASA and PFO with a TIA, oral anticoagulation (OAC) with phenprocoumon was initiated in our patient. The small PFO was not considered absolutely liable for interventional treatment with a septal occluder device and the patient was discharged after nine days in a good clinical condition. At a follow-up visit after eight months the patient had not experienced any further neurological symptoms during common daily activities under ongoing OAC.

Discussion

Given the patient’s neurological symptoms after blowing his nose and the association of ASA with PFO it can be assumed that the otherwise unexplained TIA primarily was caused by a paradoxical embolism due to right-to-left shunting in our patient. According to the neurological consultation epilepsy initially considered as differential diagnosis was not confirmed. Moreover, the cranial CT findings including missing acute ischemia or hemorrhage, respectively, and the small old intracerebellar lacunary lesion hardly caused by an embolic event, but primarily by local microangiopathic disorders56 are well compatible with the clinical diagnosis of an acute TIA.

ASA and PFO are rare, but well known cardiac abnormalities both previously described in autopsy studies,78 and nowadays more and more are found by TTE and TEE, especially in patients with preceding ischemic cerebral events.Citation1–Citation4

The prevalence of ASA in the general population varies between 1% as verified in a large autopsy seriesCitation7 and 2.2% as detected by TEE, with a base width of at least 15 mm and an excursion of at least 15 mm into the right or left atrium.Citation3

In patients with stroke or TIA, however, ASA has been reported in 7.9%–46% depending on the cut-off of the excursion of ≥ 10 or ≥ 15 mm, respectively, into either the right or left atrium and on whether all cerebral ischemic events or only cryptogenic stroke or TIA, due to possible cardiogenic embolism were included in the evaluation.Citation13

As far as the pathophysiological mechanism of this ‘saccular’ malformation is concerned a particular congenital morphology of the fossa ovalis region or interatrial pressure differences may be predisposing factors for the development of an ASA.78 Furthermore, a disorder of the cardiac connective tissue may also play a significant role in the pathogenesis of this deformity of the IAS.Citation9

The additionally detected PFO with spontaneous left-to-right shunt and a right-to-left shunt under Valsalva maneuver is an embryonic remnant and found in approximately one quarter of all adultsCitation10 and in 15%–56.3% of patients with stroke or TIA, respectively, or suspected cardioembolic cerebral event.Citation1,Citation2,Citation4 Furthermore it is interesting to mention that a PFO can be found in up to 40% of younger patients with otherwise cryptogenic stroke.Citation11 Association of ASA with PFO was described in 50%–72% of the cases in pathological studies78 and in 34%–56%, as detected by TEE, of patients with possible cardiogenic cerebral embolism.Citation2–Citation4 However, in another large clinical series ASA and PFO as detected by TTE were the source of embolism in only two of 402 consecutive patients with ischemic cardioembolic strokeCitation12 highlighting the relevance of the present case and the importance to carefully look for ASA and PFO in patients with cryptogenic stroke or TIA.

The detection of these two cardiac abnormalities is frequently associated with a preceding cerebral ischemic eventCitation1–Citation4 and therefore considered a strong predictor of stroke.Citation1

In stroke patients with ASA and PFO, however, several mechanisms leading to the cerebral ischemic event can be discussed. First of all, paradoxical embolism through the PFO after Valsalva maneuver-like procedures such as blowing the nose, as in our case, has been commonly thought to be responsible for the cerebral ischemic event.Citation1 But according to pathological findings by Silver and DorseyCitation7 and Topaz et alCitation8 direct embolization from thrombi developed within the ASA or embolization through multiple perforations of a so called cribriform ASACitation13 can also be taken into consideration as further sources of stroke. ASA may also contribute to paradoxical embolism by channeling the blood flow from the inferior vena cava towards a PFO, and thus forwarding a right-to-left shunt.Citation14 Furthermore, mitral valve prolapseCitation9 and atrial arrhythmiasCitation1 are additional potential causes for cardioembolism in stroke patients with ASA.

Although the patient has several risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, carotid stenting on the left side and an old inferior wall myocardial infarction for having a stroke or a TIA and nose blowing is a common procedure during daily life even in patients with ASA and PFO, the very close temporal relation between nose blowing, a Valsalva-like maneuver, and the neurological symptoms corresponding to a TIA primarily indicate that in this clinical situation described herein our patient had suffered a paradoxical embolic cerebral event.

Finally, it has to be conceded that the source of the suggested paradoxical embolism leading to a TIA directly after nose blowing could not be clearly discovered in our case, but at least a slight deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremities that could not be detected later any more may be primarily thought to be a common and the most probable cause for the preceding ischemic cerebral event.

Since the TIA in our patient was probably his first typical cardioembolic ischemic cerebral event, interventional correction of the small PFO with a diameter of 1.5 mm was not considered absolutely necessary, but in case of a recurrent stroke or TIA under OAC, treatment with a septal occlude device will be indicatedCitation15 keeping in mind that patients with ASA and interatrial shunt have an increased risk of recurrent stroke or TIA.Citation16

In conclusion, association of ASA with PFO should always be taken into consideration as a potential cause for paradoxical embolism in cryptogenic stroke or TIA, especially after a Valsalva-like maneuver such as nose blowing. Therefore, TEE should be performed in all clinical inconclusive situations with suspected cardioembolism to safely recognize each of those two structural abnormalities of the IAS and to initiate the optimal therapeutic regimen for secondary prevention.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient in order to be allowed to publish this case report.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MasJLPatent foramen ovale, atrial septal aneurysm and ischaemic stroke in young adultsEur Heart J19941544464498070468

- MüggeADanielWGAngermannCAtrial septal aneurysm in adult patients. A multicenter study using transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiographyCirculation19959111278527927758185

- AgmonYKhandheriaBKMeissnerIFrequency of atrial septal aneurysms in patients with cerebral ischemic eventsCirculation199999151942194410208995

- SerafiniOMisuracaGGrecoFBisignaniGManesMTVenneriNPrevalence of structural abnormalities of the atrial septum and their association with recent ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: echocardiographic evaluation in 18631 patientsItal Heart J Suppl200341394512690933

- RingelsteinEBKoschorkeSHollingAThronALambertzHMinaleCComputed tomographic patterns of proven embolic brain infarctionsAnn Neurol19892667597652604383

- LeistnerSHuebnerNFaulstichA+Increased prevalence of microangiopathic brain lesions among siblings of patients with lacunar stroke. A prospective multicenter studyEur Neurol2008593–414314718057901

- SilverMDDorseyJSAneurysms of the septum primum in adultsArch Pathol Lab Med197810226265579965

- TopazOEdwardsJEBojack-MackeySTitusJLAneurysm of fossa ovalis in adults: a pathologic studyCardiovasc Pathol200312421922512826292

- RahkoPSXuQBIncreased prevalence of atrial septal aneurysm in mitral valve prolapseAm J Cardiol19906622352372091625

- MovsowitzCPodolskyLAMeyerowitzCBJacobsLEKotlerMNPatent foramen ovale: a nonfunctional embryological remnant or a potential cause of significant pathology?J Am Soc Echocardiogr1992532592701622617

- ArboixAAlióJAcute cardioembolic stroke: an updateExpert Rev Cardiovasc Ther20119336737921438816

- Pujadas CapmanyRArboixACasañas-MuñozRAnguera-FerrandoNSpecific cardiac disoders in 402 consecutive patients with ischaemic cardioembolic strokeInt J Cardiol2004952–312913415193810

- VistariniNAielloMViganòMCribriform atrial septal aneurysmJ Am Coll Cardiol20095325240419539152

- De CastroSCartoniDFiorelliMMorphological and functional characteristics of patent foramen ovale and their embolic implicationsStroke200031102407241311022072

- MeierBFrankBWahlADienerHCSecondary stroke prevention: patent foramen ovale, aortic plaque, and carotid stenosisEur Heart J2012336705713713a713b22422912

- ComessKADeRookFABeachKWLytleNJGolbyAJAlbersGWTransesophageal echocardiography and carotid ultrasound in patients with cerebral ischemia: prevalence of findings and recurrent stroke riskJ Am Coll Cardiol1994237159816038195520