Abstract

Background

Hypertension control is a challenge globally. Barriers to optimal control exist at the patient, physician, and health system levels. Patient-related barriers in our environment are not clear. The aim of this study was to identify patient-related barriers to control of hypertension among adults with hypertension in a semiurban community in South-East Nigeria.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study of patients with a diagnosis of hypertension and on antihypertensive medication.

Results

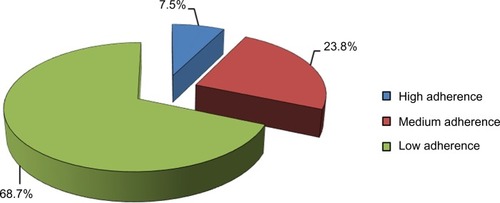

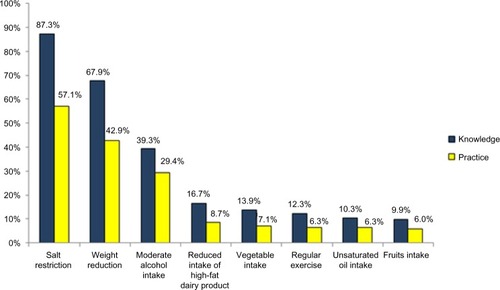

A total of 252 participants were included in the survey, and comprised 143 males (56.7%) and 109 females (43.3%). The mean age of the participants was 56.6±12.7 years, with a diagnosis of hypertension for a mean duration of 6.1±3.3 years. Among these patients, 32.9% had controlled blood pressure, while 39.3% and 27.8%, respectively, had stage 1 and stage 2 hypertension according to the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection and Evaluation of High Blood Pressure. Only 23.4% knew the consequences of poor blood pressure control and 64% were expecting a cure from treatment even when the cause of hypertension was not known. Furthermore, 68.7% showed low adherence to medication, the reported reasons for which included forgetfulness (61.2%), financial constraints (56.6%), high pill burden (22.5%), side effects of medication (17.3%), and low measured blood pressure (12.1%). Finally, knowledge and practice of the lifestyle modifications necessary for blood pressure control was inadequate among the participants.

Conclusion

Poor knowledge regarding hypertension, unrealistic expectations of treatment, poor adherence with medication, unawareness of lifestyle modification, and failure to apply these were identified as patient-related barriers to blood pressure control in this study.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

Hypertension is the leading cause of cardiovascular disease worldwide,Citation1,Citation2 and is the major cause of death and second leading cause of disability after childhood malnutrition globally.Citation3 Briganti et al reported that almost one third of Australian adults may have hypertension.Citation4 In sub-Saharan Africa, hypertension is the most rapidly increasing cardiovascular disease, affecting over 20 million people and being the most common cardiovascular cause of hospitalization and mortality.Citation5 Hypertension ranks first among the noncommunicable diseases in Nigeria,Citation6 with a prevalence ranging from 8% to 46.4% in men and women in rural and urban communities.Citation7–Citation12

Although improving the quality of care for hypertension is a priority, most hypertensive patients have inadequately controlled blood pressure,Citation13,Citation14 leading to an increased risk of coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, renal insufficiency, and stroke.Citation13 In addition, knowledge of hypertension on the part of patients is low, and control of blood pressure is generally suboptimal in rural and urban communities.Citation15–Citation17

Hypertension is considered to be controlled when systolic blood pressure is less than 140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure is less than 90 mmHg.Citation18,Citation19 Population surveys have shown that hypertension is either untreated or inadequately controlled in about 70%–75% of people worldwide, despite advances in drug treatment that have made life more tolerable for hypertensives.Citation20 Barriers to blood pressure control appear to exist at the patient, physician, and system levels. Patient-related barriers include poor knowledge concerning hypertension and its consequences,Citation21–Citation23 the side effects of antihypertensive drugs,Citation23 poor adherence with drug therapy (a major factor),Citation24,Citation25 erroneous health beliefs,Citation26,Citation27 inability to make lifestyle changes, unrealistic expectations of treatment (for example, expecting a cure),Citation28 and demographic factors (eg, socioeconomic status, educational level, age, sex).Citation29 Poor adherence with therapeutic guidelines,Citation30 inadequate understanding of therapeutic goals,Citation21,Citation31 and failure to emphasize the lifestyle modifications necessary in the management of hypertensionCitation32,Citation33 are major physician-related barriers. Further, an inefficient health care systemCitation34 and low socioeconomic statusCitation35 may present a barrier to blood pressure control, given that the inaccessibility of hospitals and high costs of screening and treatment may hinder optimal control of hypertension in the low socioeconomic groups.Citation36

Currently, safe and effective antihypertensive medications are readily available for most hypertensive patients.Citation15 Therefore, it is of paramount importance to identify barriers to obtaining optimal blood pressure control as they relate to patients. This is necessary to maximize the therapeutic effects of these drugs and to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with hypertension. Most Nigerian studies on blood pressure control and related factors in hospital settingsCitation37,Citation38 and rural/semiurban communitiesCitation17,Citation39 have not focused on patient-related barriers to hypertension control. A few have assessed the knowledge base of patientsCitation40 and their adherence to medication,Citation40–Citation42 but assessed the latter using nonvalidated tools developed by the researchers themselves for their own research purposes.

We therefore set out to identify patient-related barriers to hypertension control in a representative adult population of hypertensives in a semiurban area of South-East Nigeria. The findings of this study will add to the existing body of knowledge and help initiate concerted efforts towards curbing the rising prevalence of uncontrolled hypertension in our region.

Materials and methods

Study design and site

This was a descriptive cross-sectional questionnaire-based study carried out in Olokoro, a semiurban community in the Umuahia South local government area of Abia State, South-East Nigeria. The community is about 8 kilometers from Umuahia township, the state capital. The inhabitants are predominantly Christians and most are traders or artisans with a few civil servants and farmers.

Study population

The study population included all adults with a previous diagnosis of hypertension made by medical personnel and on antihypertensive medication at the time of the study. They were identified during a medical screening exercise carried out in Olokoro, Umuahia South local government area of Abia State, South-East Nigeria, from August 15 to 18, 2013.

Sample size and sampling

The proportion of patients adhering to their antihypertensive medication in a hospital-based study in Umuahia was 42.9%.Citation42 The sample size in this study was extrapolated from this value at a 95% confidence level with a 5% margin of error using appropriate formulae.Citation43 This gave a minimum sample size of 376. However, 390 patients were included to allow for attrition.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Consenting adults aged 18 years or older with a previous diagnosis of hypertension made by medical personnel and on antihypertensive medication were included. Patients with a psychiatric illness, an appearance of being chronically ill, or known hypertensive emergency were excluded.

Recruitment and data collection

The subjects were recruited consecutively. A structured, pretested researcher-administered questionnaire consisting of five sections was used for data collection. The first section canvassed baseline demographic characteristics, including age, sex, educational level, occupation, and duration since diagnosis of hypertension, and social characteristics, ie, alcohol consumption and smoking. The second section was designed to elicit the respondent’s knowledge of hypertension and its causes, the consequences of poor blood pressure control, and expectations of treatment. The third section addressed the respondent’s knowledge of the lifestyle measures necessary for blood pressure control and their practice of the same. The fourth section assessed adherence to antihypertensive medication using a validated eight-item scale designed for use in an outpatient setting.Citation44 In a previous study, this scale was reported to have acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.83), with items that maintained a high item-to-item correlation (>0.4 for each) and scores that correlated with blood pressure control.Citation44 The fifth section documented the participant’s blood pressure, weight, height, body mass index, urinalysis, and blood sugar. The face and content validity of the questionnaire was evaluated by a community physician, a cardiologist, and two resident doctors. The questionnaire, written in English, was translated into the local dialect by an expert in that dialect. The translated format was thereafter translated back to English by a second party. The two English versions were then cross-checked for accuracy and consistency in the questions. The interview was conducted in English and the local dialect using interpreters where necessary.

Blood pressure was measured in the nondominant arm using a mercury sphygmomanometer (Accoson, Health Care Equipment, Egham, UK) in the sitting position after resting for 3–5 minutes. Blood pressure was categorized according to the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection and Evaluation of High Blood Pressure (JNC-VII).Citation19 Height was measured using a stadiometer with the participant standing erect, barefoot and without a cap, with the occiput, back, buttock, and heel making contact with a vertical wall. Weight was recorded using a digital bathroom weighing scale.

The subjects were instructed on how to collect a midstream urine specimen. Menstruating females and those with febrile illness or clinical features suggestive of urinary tract infection were excluded from urinalysis. The participants thereafter provided urine samples that were tested using ten parameter urine strips (Chung-Do Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, Gangwon-Do, Republic of Korea). Individuals with proteinuria of 1+ or greater were considered to have significant proteinuria. Those with nitrite-positive samples were excluded from subsequent analysis as they were presumed to have urinary tract infection. Blood sugar was analyzed using an Accu-Chek® glucose meter (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The screening definition for diabetes was based on World Health Organization criteria,Citation45 which define random blood sugar of ≥11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL) as diabetes mellitus, or previous diagnosis of diabetes by a physician, or use of hypoglycemic agents.

Data protection

Data were stored using the Microsoft Excel program, kept secure, and only released for analysis when needed. Confidentiality was maintained and the anonymity of responses ensured. Personal identifiers were not collected. Permission was obtained from the local government authorities and informed consent from the participants. Anonymity of responses was ensured by nondisclosure of the identity of participants.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as the mean and standard deviation, and categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and proportions. Appropriate diagrams and tables were used to illustrate results where necessary. The chi-square test was used to determine associations between variables. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine the factors associated with the practice of lifestyle modification in those aware of these measures. Statistical significance was assumed at P<0.05.

Results

Complete data was available for 252 participants (a response rate of 64%) and used in the analysis. The general characteristics of the patients are shown in . The mean age of the patients was 56.6±12.7 years, with more males (n=143, 56.7%) than females (n=109, 43.3%). The mean duration of diagnosis of hypertension was 6.1±3.3 years. At the time of the study, 39.3% of participants had stage 1 hypertension, 27.8% had stage 2 hypertension, and 32.9% had controlled blood pressure according to JNC-VII (). There was no relationship between the educational attainment of respondents and their blood pressure control (χ2 with trend 0.53, P=0.47).

Table 1 Characteristics of study participants

Significant proteinuria was found in 12.3% of the respondents, and diabetes mellitus was found in 5.2%. Blood pressure control among respondents was not significantly associated with the presence of proteinuria (P=0.243) or diabetes mellitus (P=0.772).

A considerable number of respondents (65.1%) knew what hypertension meant and 55.6% knew at least two causes of hypertension. However, only 23.4% of respondents knew two or more complications of poor blood pressure control, and 64% were expecting a cure from treatment ().

Table 2 Participants’ basic knowledge of hypertension, causes, complications and treatment outcomes

A significant number of participants (68.7%) reported low adherence to antihypertensive medication (). The reasons cited for low adherence are shown in . The Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8 (MMAS-8) used, showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78 implying high internal consistency.

Table 3 Reason for low level of adherence among participants

There was a disparity between the participants’ knowledge of lifestyle modification in the management of hypertension and their practice of the relevant measures (). Among those aware of salt restriction as a lifestyle modification, civil servants (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 0.12; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.02–0.96) and those with a longer duration since diagnosis of hypertension (adjusted OR 0.78; 95% CI 0.68–0.89) were less likely to practice salt restriction. Respondents who were currently married were more likely to practice salt restriction (adjusted OR 2.35; 95% CI 1.10–5.00).

Figure 2 Knowledge and practice of lifestyle modification in management of hypertension among respondents.

None of the sociodemographic variables assessed were found to be associated with the likelihood of practice of regular exercise among respondents who were aware of this lifestyle modification. Those with only secondary level of formal education were less likely to attempt weight reduction, despite being aware of its importance in blood pressure control (adjusted OR 0.13; 95% CI 0.03–0.52).

Discussion

Although adequate blood pressure control (<140/90 mmHg) is a major approach in reduction of the morbidity and mortality related to cardiovascular disease, achieving this target has remained a global challenge. Better control is needed, especially among Africans, because reports have shown that they have worse hypertension-related outcomes, including higher rates of fatal stroke, heart disease, and end-stage renal disease when compared with their white counterparts.Citation46,Citation47 However, rates of adequate blood pressure control vary widely globally and in Nigeria. The low rate of blood pressure control (32.9%) obtained in this study is consistent with the 31% reported in Kano, Nigeria,Citation38 the 31.4% reported in Abeokuta, Nigeria,Citation48 and the 34% reported in the USA.Citation19 Further, it is lower than the 36% reported from Ibadan,Citation41 the 42.7% reported from Sokoto, Nigeria,Citation37 the 53.3% reported from Ilorin, Nigeria,Citation49 the 35% previously reported in Umuahia, Nigeria,Citation42 and the 39% reported in Cuba.Citation50 The majority of our study participants were traders, who tend to sit in one place to conduct their business (sedentary lifestyle) and may not undertake regular exercise. In addition, these traders spend most of their day at the market and depend on food vendors for most of their meals. Food from these sources is often salt-laden to improve taste. All these factors can adversely affect blood pressure control and contribute to low blood pressure control rates. However, the blood pressure control rate in this study was higher than the 12.4% reported in Zaria, Nigeria,Citation40 the 24.2% from Port Harcourt, Nigeria,Citation51 the 29.4% in Edo State, Nigeria,Citation7 and the 10% reported in some parts of Europe.Citation52 The mean duration since diagnosis of hypertension and hence the duration of drug treatment was higher in our study, and could account for the higher blood pressure control rate when some of these studies are compared. In general, these figures indicate that achieving optimal blood pressure control is still a challenge worldwide.

Hypertension may exist in association with other comorbidities in which there are compelling indications for use of specific medications.Citation19 Some of these comorbidities including diabetes, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, and ischemic heart disease, can influence the outcome of blood pressure control.Citation19 Proteinuria is an early indicator of kidney damage.Citation53 In the setting of hypertension, it may be a marker of renal parenchymal disease as either a complication or cause of hypertension. It can also be an indicator of nephropathy in diabetics and pre-eclampsia in pregnant women.Citation19 Unlike other studies,Citation54,Citation55 this study did not reveal a significant association between presence of proteinuria or diabetes mellitus and blood pressure control. This may be due to the smaller sample size of our study compared to these other studies.

Patient education can improve blood pressure control.Citation56 Before treatment is started, the hypertensive patient needs medical information on the meaning of hypertension, its causes, the duration of treatment, and the need for adherence to medication, lifestyle modification, and regular follow-up visits.Citation57 A well informed patient is more likely to accept treatment and comply with the physician’s prescriptions, and be less likely to discontinue treatment prematurely.Citation58 Misunderstanding of prescriptions on the part of patients (in terms of duration of use and dosing of drugs) and failure to get drug refill was reported in a study by Okeahialam.Citation59 Even though a good proportion of participants (more than 50%) seemed to have a fair understanding of hypertension and its causes (), most did not understand the complications of poor blood pressure control. In addition, a sizeable number were ignorant of the duration and expectations of treatment for hypertension. These misconceptions and knowledge gaps have been reported to be particularly critical for Africans, who may have different perceptions of hypertension and different expectations of care.Citation60 Patients whose beliefs are discordant with traditional biomedical concepts of hypertension have poorer blood pressure control than those whose beliefs are concordant.Citation60 Beliefs that hypertension is “curable” and not chronic, and that medication is needed only for hypertension-related symptoms may translate into poorer rates of medication adherence and blood pressure control.

Adherence is defined by the World Health Organization as the extent to which a person’s behavior, ie, taking medication, following a diet, and/or implementing lifestyle changes, corresponds with the recommendations made by a health care provider.Citation61 Adherence requires the patient’s active participation in a therapeutic alliance established between the patient and physician.Citation62 There are several methods available for measurement of adherence,Citation62 none of which can be considered a gold standard. The use of standardized validated questionnaires and patient self-reporting is simple, inexpensive, and regarded as the most useful method in the clinical and outpatient settings.Citation62 However, these measures are susceptible to error with increased time between visits and their results are easily distorted by patients. The low level of adherence to antihypertensive medication by the majority of participants in this study corroborates previous reports that adherence is poor in some patients with hypertension.Citation38,Citation41,Citation42,Citation63 Factors identified in this study as being responsible for low adherence are shown in . Suffice it to say that forgetting to take antihypertensive medication is not a problem that adult patients overcome. This has been attributed to competing psychosocial demands in everyday life,Citation42,Citation64 especially among traders. Physicians’ awareness of this is crucial for optimal care of adult hypertensive patients in Nigeria.

A financial impediment to drug purchase was noted in 56.6% of participants. This raises the issue of the role of the patient’s socioeconomic status in blood pressure control, as discussed in other studies.Citation17,Citation40,Citation42 Nigeria’s health expenditure is ranked among the lowest in the world,Citation65 and about 70% of Nigerians live below the poverty line.Citation66 Newer and more potent antihypertensive drugs are available, but are largely unaffordable for the majority of patients. The nature of essential hypertension as a lifelong disease, the need for daily medication, and the cost and side effects of drugs all need to be taken into consideration in the design of an effective therapeutic regimen for hypertensive individuals.

The effectiveness of self-monitoring of blood pressure in improving blood pressure control is also well documented.Citation67,Citation68 Mengden et al found average blood pressure reductions of 19.3/11.9 mmHg at 6 months in a home monitoring group versus 10.6/8.8 mmHg in a usual care group.Citation69 Some participants in our study showed evidence of home blood pressure monitoring that was quite commendable. However, 12.1% discontinued their medications when they found that their blood pressure was lower than earlier measurements. This habit is incompatible with good practice and should be discouraged.

The JNC-VIICitation19 and the Nigerian Hypertension Society guideline for the management of hypertensionCitation70 recommend lifestyle modification for all patients with hypertension or prehypertension. These modifications, previously referred to as nonpharmacologic therapy, serve as adjunctive therapy for hypertension and include weight reduction, increased physical activity, moderation of dietary sodium and alcohol intake, and following the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension eating plan. The effectiveness of these lifestyle measures in preventing and treating hypertension is well established.Citation71,Citation72 Knowledge about lifestyle modification in our study was generally poor, and the knowledge-practice discordance noted is particularly alarming. This result is consistent with other similar reports of poor knowledge and application of lifestyle measures for blood pressure control among patients with hypertension.Citation40,Citation41,Citation73

Conclusion

Poor blood pressure control in the majority of participants was an important finding in this study. Although this could be largely multifactorial, identified patient-related barriers include inadequate knowledge of the consequences of poor blood pressure control, unrealistic expectations of treatment, poor adherence to medications (forgetfulness and financial constraints being mainly responsible for this), poor knowledge of lifestyle measures, and a knowledge-practice gap in application of lifestyle measures.

Recommendations

Achieving control of hypertension requires a team effort. Although both physician and patient factors need to be addressed to improve hypertension control, emphasis should be placed on interdisciplinary team-based care utilizing health care providers such as nurses, physician assistants, and pharmacists. Team-based care has been shown to have the greatest impact of all the strategies available for improving blood pressure control.Citation74

In addition, patient education, addressing misconceptions about hypertension, regular home blood pressure monitoring, the need for consistency in drug and nondrug measures prescribed as well as regular follow-up need to be addressed at each clinic visit. Physicians should prescribe drugs which are pocket-friendly and have a low side effect profile. Up to 17.3% of our participants who were not adherent to drugs attributed this to the side effects of medications. Premature discontinuation of treatment due to drug side effects and lack of money to buy drugs interrupt consistent use of antihypertensive medication.Citation40,Citation75

Physician and health system barriers also contribute to poor blood pressure control, but these were not the focus of this study. However, they also need to be identified and corrected for any meaningful control of blood pressure to be achieved. They also represent an area for further research as few relevant data exist in the literature. These measures, if taken into consideration, will help to stem the rising tide of the hypertension pandemic and its complications in our region.

Limitations

Blood pressure control should ideally be assessed using the average of two or more consecutive blood pressure readings taken on different occasions. However, this study was carried out as part of a screening exercise in which we did not have the benefit of knowing participants’ previous blood pressure readings and there was no subsequent follow-up of the participants. Medication adherence was assessed using the Morisky’s questionnaire which has not been validated for use in this population.Citation44 Further studies are needed in our population to validate the use of this tool. The assessment of the practice of lifestyle modification among participants in this study was limited by the use of subjective responses alone. This was due to a paucity of validated tools to objectively assess this vital aspect of patient management.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- KearneyPMWheltonMReynoldsKMuntnerPWheltonPKHeJGlobal burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide dataLancet2005365945521722315652604

- KearneyPMWheltonMReynoldsKWheltonPKHeJWorldwide prevalence of hypertension: a systematic reviewJ Hypertens2004221111915106785

- MacgregorGAAfrica and salt – the need for action nowPaper presented at The Second Pan-African Meeting on Hypertension, International Forum for Hypertension Control and Prevention in AfricaMay 12–13, 2007Nairobi, Kenya

- BrigantiEMShawJEChadbanSJUntreated hypertension among Australian adults: the 1999–2000 Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab)Med J Aust2003179313513912885281

- International Conference for Cardiovascular Disease Control and Prevention in AfricaWHL Newsletter2003883 Available at http://www.worldhypertensionleague.org/Documents/newsletters/2003/whl88.pdfAccessed February 24, 2014

- AkinkugbeOONoncommunicable Disease in Nigeria: Final Report of a National SurveyLagos, NigeriaFederal Ministry of Health and Social Services1997

- OgunlesiAOsotimehinBAbbiyessukuFBlood pressure and educational level among factory workers in Ibadan, NigeriaJ Hum Hypertens1991553753801770467

- ArogundadeFSanusiAHassanMGbadegesinAOlarinoyeFOtuyemiBUndiagnosed hypertension and proteinuria in a market population in Ile Ife, NigeriaArab J Nephrol Transplant20114314114622026338

- OladapoOOSalakoLSadiqOShoyinkaKAdedapoKFalaseAOA prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors among a rural Yoruba South-Western Nigerian population; a population-based surveyCardiovasc J Afr2010211263120224842

- UlasiIIIjomaCKOnodugoODCommunity based study of hypertension and cardiometabolic syndrome in semi-urban and rural communities in NigeriaBMC Health Serv Res20101071

- OgahOSMadukweOOOnyeonoroUUCardiovascular risk factors and non-communicable diseases in Abia state, Nigeria: report of a community-based surveyInt J Med Biomed Res2013215768

- OnwubereBJEjimECOkaforCIPattern of blood pressure indices among the residents of a rural community in South East NigeriaInt J Hypertens2011201162107422121475

- [No authors listed]The Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VI)Arch Intern Med199715721241324469385294

- BerlowitzDRAshASHickeyECInadequate management of blood pressure in a hypertensive populationN Engl J Med199833927195719639869666

- WangLWeiTBlood pressure control in patients with hypertension: a community-based studyClin Exp Hypertens2006281414616443563

- WhiteFWangLJelinekHAwareness and pharmacotherapy of hypertension in a rural communityMed Princ Pract200918426126519494531

- OmuemuVOOkogieOHOmuemuCEAwareness of high blood pressure status, treatment and Control in a rural community in Edo StateNiger J Clinical Pract200710320821218072446

- WhitworthJA2003 World Health Organization (WHO)/International Society of Hypertension (ISH) statement on management of hypertensionJ Hypertens200321111983199214597836

- ChobanianAVBakrisGLBlackHRSeventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood PressureHypertension20034261206125214656957

- ChalmersJMacMahonSManciaG1999 World Health Organization-International Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the management of hypertension. Guidelines sub-committee of the World Health OrganizationClin Exp Hypertens1999215–61009106010423121

- OdedosuTSchoenthalerAVieiraDLAgyemangCOgedegbeGOvercoming barriers to hypertension control in African AmericansCleve Clin J Med2012791465622219234

- DouglasJGFerdinandKCBakrisGLSowersJRBarriers to blood pressure control in African Americans. Overcoming obstacles is challenging, but target goals can be attainedPostgrad Med20021124515212400149

- KnightELBohnRLWangPSGlynnRJMogunHAvornJPredictors of uncontrolled hypertension in ambulatory patientsHypertension200138480981411641291

- ChobanianAVControl of hypertension – an important national priorityN Engl J Med2001345753453511519509

- MillerNHHillMKottkeTOckeneISThe multilevel compliance challenge: recommendations for a call to action. A statement for healthcare professionalsCirculation1997954108510909054774

- BlumhagenDHypertension: a folk illness with a medical nameCult Med Psychiatry1980431972247408522

- MeyerDLeventhalHGutmannMCommon-sense models of illness: the example of hypertensionHealth Psychol1985421151354018002

- OgedegbeGMancusoCAAllegranteJPExpectations of blood pressure management in hypertensive African-American patients: a qualitative studyJ Natl Med Assoc200496444244915101664

- LangTSocial and economic factors as obstacles to blood pressure controlAm J Hypertens19981179009029683060

- MehtaSSWilcoxCSSchulmanKATreatment of hypertension in patients with comorbidities: results from the study of hypertensive prescribing practices (SHyPP)Am J Hypertens1999124 Pt 133334010232492

- WangLPhysician-related barriers to hypertension managementMed Princ Pract200413528228515316262

- HicksLSShaykevichSBatesDWAyanianJZDeterminants of racial/ethnic differences in blood pressure management among hypertensive patientsBMC Cardiovasc Disord2005511615972095

- HajjarIMillerKHirthVAge-related bias in the management of hypertension: a national survey of physicians’ opinions on hypertension in elderly adultsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2002578487491

- SheaSMisraDEhrlichMHFieldLFrancisCKCorrelates of nonadherence to hypertension treatment in an inner-city minority populationAm J Public Health19928212160716121456334

- BoneLRHillMNStallingsRCommunity health survey in an urban African-American neighborhood: distribution and correlates of elevated blood pressureEthn Dis2000101879510764134

- WeeLEKohGCIndividual and neighborhood social factors of hypertension management in a low-socioeconomic status population: a community-based case-control study in SingaporeHypertens Res201235329530322089533

- IsezuoASNjokuCHBlood pressure control among hypertensives managed in a specialised health care setting in NigeriaAfr J Med Med Sci2003321657015030069

- SaniMUMijinyawaMSAdamuBAbduABorodoMMBlood pressure control among treated hypertensives in a tertiary health institutionNiger J Med200817327027418788251

- ObinnaIEPatrickOUIzuchukwuLNPrevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in a Nigerian populationHealth Psychol20102731735

- OyatiAIOrogadeAADanbauchiSSAzuhPCAwareness, treatment and control of hypertension among hypertensives in ZariaJournal of Medicine in the Tropics2011132139144

- SalakoBLAjoseFALawaniEBlood pressure control in a population where antihypertensives are given freeEast Afr Med J2003801052953115250626

- IlohGUPOfoeduJNNjokuPUAmadiANGodswill-UkoEUMedication adherence and blood pressure control amongst adults with primary hypertension attending a tertiary hospital primary care clinic in Eastern NigeriaAfr J Prim Health Care Fam Med201351446452

- AraoyeMOResearch Methodology with Statistics for Health and Social SciencesIlorin West, NigeriaNathadex Publishers2004

- MoriskyDEAngAKrousel-WoodMWardHJPredictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient settingJ Clin Hypertens (Greenwich)200810534835418453793

- [No authors listed]Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. National Diabetes Data GroupDiabetes1979281210391057510803

- GilesWHKittnerSJHebelJRLosonczyKGSherwinRWDeterminants of black-white differences in the risk of cerebral infarction. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Epidemiologic Follow-up StudyArch Intern Med199515512131913247778964

- KlagMJWheltonPKRandallBLNeatonJDBrancatiFLStamlerJEnd-stage renal disease in African-American and white men. 16-year MRFIT findingsJAMA199727716129312989109467

- AyodeleOEAlebiosuCOSalakoBLDifferential control of systolic and diastolic blood pressure in blacks with essential hypertensionJ Natl Med Assoc200496331031415040512

- OlanrewajuTOAderibigbeAChijiokeADescriptive analysis of blood pressure control among treated hypertensive patients in a tertiary hospital in NigeriaAfr J Med Med Sci201140320721222428514

- CooperRSOrdunezPFerrerMDIMunozJCBEspinosa-BritoACardiovascular disease and associated risk factors in Cuba: prospects for prevention and controlAm J Public Health20069619410116317211

- AkpaMRAlasiaDDEmem-ChiomaPCAn appraisal of hospital based blood pressure control in Port Harcourt NigeriaNigerian Health Journal200881–22730

- Wolf-MaierKCooperRSKramerHHypertension treatment and control in five European countries, Canada, and the United StatesHypertension2004431101714638619

- National Kidney FoundationKDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney diseaseKidney Int Suppl20133119

- DavisTEMillnsHStrattonIMHolmanRRTurnerRCGroup UKPDSRisk factors for stroke in type 2 diabetes mellitus: United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) 29Arch Intern Med1999159101097110310335687

- FaganTCSowersJType 2 diabetes mellitus: greater cardiovascular risks and greater benefits of therapyArch Intern Med1999159101033103410335678

- GreenLWLevineDMWolleJDeedsSDevelopment of randomized patient education experiments with urban poor hypertensivesPatient Couns Health Educ19791310611110242310

- LevineDMGreenLWDeedsSGChwalowJRussellRPFinlayJHealth education for hypertensive patientsJAMA19792411617001703430732

- IsoHShimamotoTYokotaKSankaiTJacobsDRJrKomachiYCommunity-based education classes for hypertension control. A 1.5-year randomized controlled trialHypertension19962749689748613276

- OkeahialamBNAdherence and preference issues in anti-hypertensive therapy: experience from a private medical facility in Jos, NigeriaJournal of Medicine in the Tropics2011131114

- Heurtin-RobertsSReisinEThe relation of culturally influenced lay models of hypertension to compliance with treatmentAm J Hypertens19925117877921457078

- World Health OrganisationEssential Medicines and Health Products Information Portal. Adherence to long-term therapy – evidence for action2003 Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js4883e/6.1.1.htmlAccessed February 21, 2014

- OsterbergLBlaschkeTAdherence to medicationN Engl J Med2005353548749716079372

- BramleyTJGerbinoPPNightengaleBSFrech-TamasFRelationship of blood pressure control to adherence with antihypertensive monotherapy in 13 managed care organizationsJ Manag Care Pharm200612323924516623608

- WangPSBohnRLKnightENon-compliance with antihypertensive medications, the impact of depressive symptoms and psychosocial factorsJ Gen Intern Med200217750451112133140

- World Health OrganisationWorld health report on reducing risks, promoting healthy lifeGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organisation2002 Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2002/en/Accessed May 22, 2014

- Central Intelligence AgencyThe World Factbook – Nigeria52005 Available from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ni.htmlAccessed February 24, 2014

- YarowsSAJuliusSPickeringTGHome blood pressure monitoringArch Intern Med200016091251125710809027

- JohnsonALTaylorDWSackettDLDunnettCWShimizuAGSelf-recording of blood pressure in the management of hypertensionCan Med Assoc J1978119910341039369673

- MengdenTUenSBaulmannJVetterHSignificance of blood pressure self-measurement as compared with office blood pressure measurement and ambulatory 24-hour blood pressure measurement in pharmacological studiesBlood Press Monit20038416917214517481

- [No authors listed]Guidelines for the management of hypertension in Nigeria51996 Available from: http://www.nigerianheart.org/downloads/management_of_hypertension.pdfAccessed November 24, 2013

- MooreTJConlinPRArdJSvetkeyLPDASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet is effective treatment for stage 1 isolated systolic hypertensionHypertension200138215515811509468

- AppelLJChampagneCMHarshaDWEffects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trialJAMA2003289162083209312709466

- IkeSOAniebuePNAniebueUUKnowledge, perceptions and practices of lifestyle-modification measures among adult hypertensives in NigeriaTrans R Soc Trop Med Hyg20101041556019733378

- WalshJMMcDonaldKMShojaniaKGQuality improvement strategies for hypertension management: a systematic reviewMed Care200644764665716799359

- AkpaMRAgomuohDROdiaOJDrug compliance among hypertensive patients in Port Harcourt, NigeriaNiger J Med200514555715832644