Abstract

Purpose

General practitioners have an important role in diagnosing a variety of patients, including psychiatric patients with complicated symptoms. We evaluated the relationship between physical symptoms and psychiatric disorders in general internal medicine (GIM) outpatients in a Japanese university hospital.

Materials and methods

We coded the symptoms and diagnoses of outpatients from medical documents using the International Classification of Primary Care, second edition (ICPC-2). The participants were new outpatients who consulted the GIM outpatient division at Jichi Medical University Hospital in Tochigi, Japan from January–June, 2012. We reviewed all medical documents and noted symptoms and diagnoses. These were coded using ICPC-2.

Results

A total of 1,194 participants were evaluated, 148 (12.4%) of whom were diagnosed as having psychiatric disorders. The prevalence of depression, anxiety disorder, and somatization was 19.6% (number [n] =29), 14.9% (n=22), and 14.2% (n=21), respectively, among the participants with psychiatric disorders. The presence of several particular symptoms was associated with having a psychiatric disorder as compared with the absence of these symptoms after adjusting for sex, age, and the presence of multiple symptoms (odds ratio [OR] =4.98 [95% confidence interval {CI}: 1.66–14.89] for palpitation; OR =4.36 [95% CI: 2.05–9.39] for dyspnea; OR =3.46 [95% CI: 1.43–8.36] for tiredness; and OR =2.99 [95% CI: 1.75–5.13] for headache).

Conclusion

Not only the psychiatric symptoms, but also some physical symptoms, were associated with psychiatric disorders in GIM outpatients at our university hospital. These results may be of help to general practitioners in appropriately approaching and managing patients with psychiatric disorders.

Introduction

Improvements in the health care system have contributed to an increasingly aged population and a higher prevalence of various chronic disorders and multimorbidity.Citation1,Citation2 One study in Australia showed that multimorbidity was commonly associated with psychiatric problems.Citation3 Up to one-third of patients in a primary care setting complained of medically unexplained symptoms (MUS).Citation4 Agüera et alCitation5 reported that the prevalence of undiagnosed mood disorders in patients with unexplained chronic pain in primary care was 80.4%. It has been reported that a number of physical symptoms are associated with psychiatric disorders, and that some particular symptoms are predictive of psychiatric disorders.Citation6–Citation8

Patients with somatic symptoms caused by psychiatric disorders tend to frequently change doctors without referral, seek unnecessary examinations, receive treatment without consulting psychiatrists, or visit a tertiary hospital directly.Citation9 Failure to recognize the psychiatric disorder has been associated with undertreatment, greater impairment, and longer duration of illness.Citation7,Citation10 The International Classification of Primary Care, second edition (ICPC-2) allows for the coding of reasons for encounters in an episode of care, applied to both physical and mental issues, specifically for use in primary care.Citation11–Citation13

The EPIsode CONstructor (EPICON), which is a useful computerized system for grouping diagnoses and estimating morbidity from electronic medical records, has already been established in northwestern Europe, Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands.Citation14,Citation15 Because such a system has yet to be developed in Japan, ICPC coding has been performed by checking all pertinent medical documents despite the cost in terms of time and effort involved. Even though a large-scale study could not be conducted, there have been several reports that reveal the frequency of reasons for encounters in some primary care settings in Japan.Citation16,Citation17 ICPC-2 was translated into Japanese and its broad use was attempted by the ICPC working team of the Japan Primary Care Association, because ICPC coding was thought to be useful for understanding the medical needs in the primary care setting. The role of general practitioners (GPs) in mental health care has been increasing because of the rising burden of mental disorders.Citation18–Citation20 GPs are expected to become gatekeepers for patients with psychiatric disorders whose somatic symptoms have not been diagnosed as mental problems.Citation21 Yamada et alCitation17 assessed the accuracy of a family physician’s diagnosis of depression and alcoholism. Integrated care of mental health by GPs was reported to improve patient satisfaction.Citation22

Taking these changes in mental health care into consideration, evidence useful in the prediction of mental disorders would be very welcome and research should also be advanced in Japan, which is a special setting characterized by certain features, such as easy access to any medical provider.

This study was undertaken to clarify the relationship between symptoms and psychiatric disorders in a general internal medicine (GIM) outpatient division in a university hospital using ICPC-2 to code the symptoms and diagnoses of outpatients.

Materials and methods

Study design

An observational design was employed.

Patients

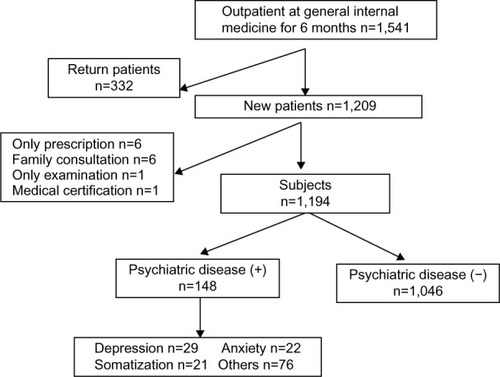

The present participants comprised new outpatients who consulted the GIM division. The number of outpatients in the GIM division was 1,541 from January–June 2012. We identified the 1,209 participants who complained of new symptoms after excluding any returning patients who consulted us for the same symptom as in the previous month. We excluded the patients who came only to receive prescriptions (number [n] =6), family consultation (n=6), examination only (n=1), and medical certification only (n=1). The final number of eligible participants was 1,194 for this study ().

Setting

The Jichi Medical University Hospital (Tochigi, Japan) has 1,132 beds and provides not only advanced medical care, but also primary care for the local community. The GIM division has 16 beds and manages both inpatients and outpatients. It diagnoses and treats patients with common disorders, multiple health problems, or symptoms of unknown origin. We treat patients both with and without referrals. While the percentage of patients with referral for the entire hospital is 60%, that for our division is 30%. Japan has a public health insurance system covering most of the population, allowing them to consult all types of health care providers and to consult most physicians without referral.Citation9

The outpatients without referral are guided to make a brief stop at the information counter where a doctor recommends the most appropriate department or division for their consultation. Those who need to see generalists are recommended to visit the division of GIM. Some of these patients often have fears regarding their own symptoms because no doctors approached or managed their health problems of unknown origin. Therefore, they started to insist on obtain ing a guaranteed high level of service. The role of GIM is thought to include the management of mental problems that cause physical symptoms.

Measurements

We evaluated symptoms and diagnoses from the patients’ medical records and coded them according to the ICPC-2.Citation23 The ICPC-2 code consisted of 17 chapters (A–Z) and seven components, including symptoms and diagnoses. Six physicians who practice in the outpatient clinic of the GIM division attended a tutorial about coding by ICPC-2. In the tutorial, they were informed of the methods extracting symptoms and diagnosis from medical documents and coding them in ICPC. After the tutorial, they coded the medical documents of the participants. Two investigators later checked all coded data sheets for accuracy. If a discrepancy in the coding between investigators was found, one author (JM), who is a member of the ICPC working team of the Japan Primary Care Association, provided the final classification code. If the patients had multiple symptoms, we selected the symptom noted first by a physician and coded it for the analysis. We gave a final diagnosis and coded it after we checked the current medical history and the following medical documents as well. If the participants had multiple diagnoses, we noted up to four diagnoses. Those diagnoses and the coding of psychiatric disorders were not obtained by psychological tests, but by clinical diagnoses by the GPs or the result of psychiatric consultation. If the participants had at least one psychiatric diagnosis, they were defined as having a psychiatric disorder regardless of the existence of other diagnoses.

Data analysis

A comparison of various characteristics between the groups with and without a psychiatric disorder was performed using the chi-squared test for nominal variables and the Student’s t-test for continuous variables. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated by multivariable logistic regression to evaluate the risk of having a psychiatric disorder for the participants with each symptom. We analyzed the association between common somatic symptoms and psychiatric disorders using multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted by sex, age, and the presence of multiple symptoms. The statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS version 19.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) computer software package. A probability value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics

The institutional review board of Jichi Medical University approved this study.

Results

The participants’ ages ranged from 15 to 92 years (mean age: 50.5±19.3 years) and 686 (57.5%) of the 1,209 participants were men. Of all the participants, 245 (20.5%) were referred by other clinics. A total of 148 (12.1%) were diagnosed as having psychiatric disorders. shows the characteristics of the study participants between those with and without psychiatric disorders. Those with psychiatric disorders were younger than those without them. The number of symptoms in those with psychiatric disorders was greater than that in those without them, and the proportion of the participants with two or more symptoms among those with psychiatric disorders was greater than among those without the disorders. There were 148 participants with psychiatric disorders (). Of those, the most frequent diagnoses were P76 (depression; 19.6%), P99 (psychological disorders, other; 16.2%), P74 (anxiety disorder; 14.9%), P75 (somatization; 14.2%), and P06 (sleep disturbance; 11.5%). The P99 was defined to include an unspecified status that was attributed to psychosomatic factors. shows the common symptoms of the participants with psychiatric disorders.

Table 1 Comparison of the characteristics between those with present or absent psychiatric disorders

Table 2 Prevalence of each symptom with psychiatric disorders

shows the risk of having a psychiatric disorder for those participants with common somatic symptoms. The participants with psychiatric symptoms showed obvious sleep disturbance (OR =73.99; 95% CI: 8.97–609.96). The presence of particular physical symptoms was associated with having a psychiatric disorder, as compared with their absence after adjusting for sex, age, and the presence of multiple symptoms (OR =4.98 [95% CI: 1.66–14.89] for palpitation; OR =4.36 [95% CI: 2.05–9.39] for dyspnea; OR =3.46 [95% CI: 1.43–8.36] for tiredness; and OR =2.99 [95% CI: 1.75–5.13] for headache).

Table 3 Risk of having psychiatric disorders among the subjects with common somatic symptoms

Discussion

In our study, participants in whom palpitation, dyspnea, tiredness, or headache was identified were more likely to have psychiatric disorders. Physical symptoms of the participants with psychiatric disorders turned out to be common.

Various patient factors might explain why many patients with a psychiatric disorder complained of only physical symptoms. First, they may not be good at expressing their own mental condition.Citation24 Additionally, they may want to be reassured by consulting a health service and being examined repeatedly, because of a fear that they are suffering from a serious physical illness.Citation25 Physician factors might include an inappropriate patient–physician relationship that may not provide an opportunity for patients to express their psychiatric symptoms to physicians.

GPs at university hospitals, who often encounter such difficult patients, should be competent to exclude critical illness and determine the possibility of psychiatric disorders.Citation26–Citation28 Rasmussen et alCitation7 reported that headache, chest pain, dizziness, sleep disturbance, dyspnea, and tiredness were significantly related to the presence of psychiatric disorders in rural primary care adults. These symptoms were similar to those found in our study with the exception of palpitation. Barsky et alCitation29 reported that 29% of 82 outpatients who complained of palpitation without any abnormalities on ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring had a current psychiatric disorder, and 83% of these patients had major depression or panic disorder. In clinical practice, dyspnea is frequently derived from critical conditions – ie, ischemic heart disease, cardiac failure, ventricular arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, pulmonary embolism, other pulmonary disorders, or hematological or metabolic disorders. Han et alCitation30 reported that the presence of the urge to breathe, affective dyspnea, anxiety, and tingling pointed to a diagnosis of MUS, whereas the reporting of wheezing, cough and sputum, and palpitation were more likely to be due to cardiopulmonary diseases causing dyspnea.

One limitation of our study was that the number of participants was relatively small for identifying the symptoms predictive of psychiatric disorders. Coding the ICPC from each medical document was a heavy burden for the researchers. The lack of an automatic conversion system for coding the ICPC from the medical records made it difficult to collect sufficient data. Another limitation was that psychiatric disorders might be underdiagnosed in the participants. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders was 12.1% in our study, while it was 22.6% in Rasmussen’s study using the primary care evaluation of mental disorders (PRIME-MD) in all the outpatient primary care adults.Citation7 Olivera et alCitation31 reported that the prevalence of psychiatric disorders was 46.1% in the elderly, as determined by psychogeriatric screening instruments. The proportion of participants with psychiatric disorders in our study might have been underestimated because the diagnoses of psychiatric disease were based on clinical interviews alone.

Conclusion

In conclusion, not only psychiatric symptoms, but also palpitation, dyspnea, tiredness, and headache, were associated with the physical symptoms of psychiatric disorders in outpatients consulting the GIM division at one Japanese university hospital. The diagnostic accuracy of psychiatric disorders in patients with MUS could lead to appropriate treatment and health care cost reduction. These results may help GPs to diagnose and manage patients with psychiatric disorders appropriately.

Author contributions

YI contributed to the conception and design of the study, the acquisition of data, the analysis and interpretation of data, and the writing and revision of the manuscript; TT, JM, SI, and MM contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of data, and the writing and revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Ayako Noda, Takashi Sekiguchi, Takeshi Tanabe, Reiko Yamamoto, Shinichi Uchida, and Hidehiko Kamiyama contributed to the acquisition of data. We thank John Gelblum for his critical reading of the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- RizzaAKaplanVSennORosemannTBhendHTandjungRFIRE study groupAge- and gender-related prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care: the Swiss FIRE projectBMC Fam Pract20121311323181753

- BarnettKMercerSWNorburyMWattGWykeSGuthrieBEpidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional studyLancet20123809836374322579043

- BrittHCHarrisonCMMillerGCKnoxSAPrevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in AustraliaMed J Aust20081892727718637770

- KroenkeKPriceRKSymptoms in the community. Prevalence, classification, and psychiatric comorbidityArch Intern Med199315321247424808215752

- AgüeraLFaildeICervillaJADíaz-FernándezPMicoJAMedically unexplained pain complaints are associated with underlying unrecognized mood disorders in primary careBMC Fam Pract2010111720199657

- KroenkeKSpitzerRLWilliamsJBPhysical symptoms in primary care. Predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairmentArch Fam Med1994397747797987511

- RasmussenNHBernardMEHarmsenWSPhysical symptoms that predict psychiatric disorders in rural primary care adultsJ Eval Clin Pract200814339940618373579

- JacksonJLHoustonJSHanlingSRTerhaarKAYunJSClinical predictors of mental disorders among medical outpatientsArch Intern Med2001161687587911268232

- GuoYKurokiTYamashiroSKoizumiSIllness behaviour and patient satisfaction as correlates of self-referral in JapanFam Pract200219432633212110549

- OrmelJKoeterMWvan den BrinkWvan de WilligeGRecognition, management, and course of anxiety and depression in general practiceArch Gen Psychiatry19914887007061883252

- SolerJKOkkesIWoodMLambertsHThe coming of age of ICPC: celebrating the 21st birthday of the International Classification of Primary CareFam Pract200825431231718562335

- RosendalMVedstedPChristensenKSMothGPsychological and social problems in primary care patients – general practitioners’ assessment and classificationScand J Prim Health Care2013311434923281962

- GaskLKlinkmanMFortesSDowrickCCapturing complexity: the case for a new classification system for mental disorders in primary careEur Psychiatry200823746947618774269

- BiermansMCElbersGHVerheijRAJan van der VeenWZielhuisGARobbéPFExternal validation of EPICON: a grouping system for estimating morbidity rates using electronic medical recordsJ Am Med Inform Assoc200815677077518755995

- BiermansMCde BakkerDHVerheijRAGravesteinJVvan der LindenMWRobbéPFDevelopment of a case-based system for grouping diagnoses in general practiceInt J Med Inform200877743143917870659

- TakeshimaTKumadaMMiseJReasons for encounter and diagnoses of new outpatients at a small community hospital in Japan: an observational studyInt J Gen Med2014725926924940078

- YamadaKMaenoTWazaKSatoTUnder-diagnosis of alcohol-related problems and depression in a family practice in JapanAsia Pac Fam Med200871318973707

- MurrayCJVosTLozanoRDisability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010Lancet201238098592197222323245608

- OlfsonMKroenkeKWangSBlancoCTrends in office-based mental health care provided by psychiatrists and primary care physiciansJ Clin Psychiatry201475324725324717378

- FortinMLapointeLHudonCVanasseANtetuALMaltaisDMultimorbidity and quality of life in primary care: a systematic reviewHealth Qual Life Outcomes200425115380021

- OiesvoldTSandlundMHanssonLFactors associated with referral to psychiatric care by general practitioners compared with self-referralsPsychol Med19982824274369572099

- KhadiviRShakeriMGhobadiSThe efficiency of mental health integration in primary health care: a ten-year StudyInt J Prev Med20123Suppl 1S139S14522826756

- HiroshiSNobusukeFMasaakiYInternational Classification of Primary Care, second edition (ICPC-2)Tokyo, JapanJapan Primary Care Association2002216

- NemiahJCA reconsideration of psychological specificity in psychosomatic disordersPsychother Psychosom198238139457146275

- BurtonCMcGormKRichardsonGWellerDSharpeMHealthcare costs incurred by patients repeatedly referred to secondary medical care with medically unexplained symptoms: a cost of illness studyJ Psychosom Res201272324224722325706

- SmithRCLylesJSGardinerJCPrimary care clinicians treat patients with medically unexplained symptoms: a randomized controlled trialJ Gen Intern Med200621767167716808764

- LittlePEverittHWilliamsonIObservational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultationsBMJ2001323731890891111668137

- Cannarella LorenzettiRJacquesCHDonovanCCottrellSBuckJManaging difficult encounters: understanding physician, patient, and situational factorsAm Fam Physician201387641942523547575

- BarskyAJDelamaterBAClancySAAntmanEMAhernDKSomatized psychiatric disorder presenting as palpitationsArch Intern Med199615610110211088638998

- HanJZhuYLiSThe language of medically unexplained dyspneaChest2008133496196818263684

- OliveraJBenabarreSLorenteTPrevalence of psychiatric symptoms and mental disorders detected in primary care in an elderly Spanish population. The PSICOTARD Study: preliminary findingsInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200823991592118311851