Abstract

Objective

Dizziness and vertigo are highly prevalent symptoms among patients presenting at primary care clinics, and peripheral vestibular disorder (PVD) is their most frequent cause. However, the incidence of PVD has not been well documented. This study aimed to investigate the incidence of dizziness, vertigo, and PVD among patients presenting at a primary care clinic.

Design

This was an observational study.

Setting and participants

Between November 2011 and March 2013, we observed 393 patients, all at least 20 years old, who had been treated for chronic diseases such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus for at least 6 months at a primary clinic (Oki Clinic) in Japan.

Outcome

The main outcome of interest was new incidence of dizziness, vertigo, and PVD events. During the 1-year follow-up period, the otorhinolaryngologist diagnosed and reported new PVD events.

Results

The mean age of the 393 participants at entry was 65.5 years. Of the study participants, 12.7%, 82.4%, and 92.6% had diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, respectively. We followed up all the participants (100%). During the 662.5 person-years of follow-up, 121 cases of dizziness or vertigo (dizziness/vertigo) and 76 cases of PVD were observed. The incidence of dizziness/vertigo and PVD was 194.7 (95% confidence interval: 161.6–232.6) per 1,000 person-years and 115.7 (95% confidence interval: 92.2–142.6) per 1,000 person-years, respectively. There were 61 cases of acute peripheral vestibulopathy, 12 of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, and three of Meniere’s disease among the 76 PVD patients.

Conclusion

We reported the incidence of dizziness/vertigo among Japanese primary care clinic patients, which was higher than that usually observed in the general population. Furthermore, we described the incidence of PVD and found that it was a major cause of dizziness/vertigo.

Introduction

Dizziness and vertigo are among the most common community health symptoms.Citation1,Citation2 They are frequent chief complaints in hospitals,Citation3,Citation4 emergency departments,Citation5 and primary care clinics.Citation6–Citation8 Furthermore, they are known to be associated with declining quality of life and increased functional disability.Citation9,Citation10 Therefore, the social and medical costs of these persistent symptoms need to be considered.Citation8

Prevalence of dizziness/vertigo was examined within the general population and in primary care settings.Citation1,Citation2,Citation10–Citation13 Some previous studies have reported on the frequency of patients who complained of dizziness/vertigo at primary care clinics.Citation7,Citation8 The incidence of dizziness/vertigo was also examined among patients who visited their family physicians.Citation2

The diagnostic management of dizziness/vertigo is challenging for physicians,Citation8,Citation14,Citation15 because they occur as a result of many diseases; however, fatal diseases are not often included in the diagnoses of primary care patients who complain of these conditions.Citation6–Citation8 Peripheral vestibular disorder (PVD) is the most frequent cause of dizziness/vertigo.Citation14,Citation15 PVD indicates a limited disorder of the cranial nerve VIII and all its distal structures. Patients with PVD demonstrate nystagmus to the contralateral side which is suppressed with visual fixation. Nystagmus improves with gaze toward the lesion and worsens with gaze in the direction opposite to the lesion.Citation16 PVD is distinguishable from central vestibular disorders and includes acute peripheral vestibulopathy (APV), benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), and Meniere’s disease (MD).Citation17

The frequency of PVD patients who visit emergency rooms and primary care clinics has been reported in previous studies,Citation5–Citation8 and the prevalence of dizziness/vertigo that was suspected to be due to PVD was also examined within the community.Citation18 However, the diagnosis of PVD in these studies was not objective because it was based on answers to questionnaire surveys.Citation18 In addition, PVD incidence within primary care settings was unclear.Citation5,Citation13,Citation14

We followed-up with patients who were being treated at a primary care clinic and investigated the incidence of dizziness/vertigo and PVD using clear diagnostic criteria under the guidance of a professional otorhinolaryngologist.

Method

Study design

This was an observational study.

Participants and setting

Between November 2011 and March 2013, we observed 393 patients who had been treated for chronic diseases, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus for at least 6 months at a primary care clinic (Oki Clinic). All subjects were at least 20 years old, and we followed each of them for at least 1 year. The Oki Clinic is a primary care clinic that was established in 1981. It is located in Yuki city, in the western part of Ibaraki Prefecture. Three physicians – a board certified otorhinolaryngologist, a board certified neurosurgeon, and a board certified member of the Japanese Society of Internal Medicine – who work at the Oki Clinic were the doctors who followed-up with the participants.

Measurements at baseline

We examined age, sex, smoking status (never, former, or current), Brinkman Index (daily number of cigarettes × years), drinking status (never, occasionally, or current), ethanol intake (g per day), systolic blood pressure (mmHg), diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL), triglycerides (mg/dL), glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c; National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program) (%), and serum creatinine (mg/dL). Dyslipidemia was defined as low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥140 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol <40 mg/dL, triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL, total cholesterol ≥220 mg/dL, or use of anti-hyperlipidemic medication.Citation19,Citation20 Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or use of anti-hypertensive medication.Citation21,Citation22 Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dL, non-fasting plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL, HbA1c (National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program) ≥6.5%, or use of anti-hyperglycemic medication.Citation23,Citation24

Outcome

The main outcomes of interest were new dizziness, vertigo, and new PVD events. During the 1-year follow-up period, the participants who experienced dizziness/vertigo had a medical consultation within a few days after the onset of new dizziness/vertigo, and the board certified otorhinolaryngologist who worked at Oki Clinic diagnosed and reported new PVD events in reference to medical history and clinical views according to the relevant diagnostic guidelines. Dizziness was defined as the sensation of disturbed or impaired spatial orientation without a false or distorted sense of motion, and vertigo was defined as the sensation of self-motion when no self-motion is occurring or the sensation of distorted self-motion during an otherwise normal head movement.Citation25 We classified PVD according to the relevant diagnostic guidelines.Citation17 PVD included APV, BPPV, and MD, and we adopted the following strict diagnostic criteria about these three diseases.

Clinical diagnostic criteria for APV

APV was defined as fulfilling all of the following three criteria: 1) rotatory vertigo lasting longer than 1 minute and being associated with persistent horizontal, spontaneous nystagmus; 2) ataxia; and 3) no sign of cochlear or central nerve involvement.Citation26,Citation27

Clinical diagnostic criteria for BPPV

BPPV was defined as fulfilling all of the following four criteria: 1) vertigo associated with a characteristic mixed torsional and vertical nystagmus provoked by the Dix–Hallpike test; 2) a latency (typically of 1 to 2 seconds) between the completion of the Dix–Hallpike test and the onset of vertigo and nystagmus; 3) the paroxysmal nature of the provoked vertigo and nystagmus (ie, an increase and then a decline over a period of 10 to 20 seconds); and 4) fatigue (ie, a reduction in vertigo and nystagmus if the Dix–Hallpike test is repeated).28,29

Clinical diagnostic criteria for MD

MD was defined as fulfilling all of the following three criteria: 1) two or more definitive spontaneous episodes of vertigo lasting 20 minutes or longer; 2) audiometrically documented hearing loss on at least one occasion; and 3) tinnitus or aural fullness in the treated ear.Citation30,Citation31

Analysis

All analyses were performed using Stata, version 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Data are presented as means ± standard deviations and population percentages. To determine the incidence of dizziness and vertigo, we calculated the number of patients who consulted the Oki Clinic otorhinolaryngologist for new dizziness, vertigo, and PVD events. The incidence were calculated per 1,000 person-years. We used the Kaplan–Meier curve to show and estimate the cumulative incidence for the endpoints of new dizziness, vertigo, and PVD.

Ethics

This study was approved by the clinical research institutional review board of Jichi Medical University.

Result

The baseline characteristics of the 393 study participants are shown in . The mean age of the participants at entry was 65.5 years, and 33.8% were men. Of the 393 study participants, 12.7%, 82.4%, and 92.6% had diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, respectively.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the 393 study participants

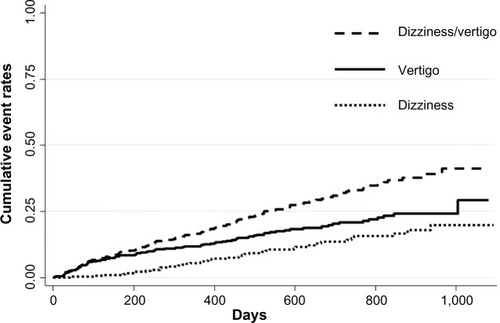

We followed-up with all 393 participants (100%; 393/393) for 633.0 days (median). During the 662.5 person-years of follow-up, there were 121 new events of dizziness/vertigo, and the incidence of dizziness/vertigo was 194.7 (95% confidence interval: 161.6–232.6) per 1,000 person-years. shows the unadjusted cumulative event rates for dizziness and vertigo. There were 42 cases of dizziness and 79 cases of vertigo.

Figure 1 Unadjusted cumulative event rates for the endpoints of dizziness and vertigo.

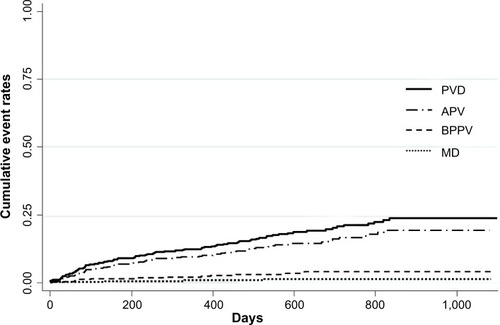

In addition, 76 new PVD (63.0%) events were observed, and the incidence of PVD was 115.7 (95% confidence interval: 92.2–142.6) per 1,000 person-years. shows the cumulative event rates for APV, BPPV, and MD. There were 61 (80.3%) cases of APV, 12 (15.8%) of BPPV, and three (3.9%) of MD among the 76 PVD patients.

Figure 2 Unadjusted cumulative event rates for the endpoints of APV, BPPV, and MD.

Abbreviations: PVD, peripheral vestibular disorder; APV, acute peripheral vestibulopathy; BPPV, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo; MD, Meniere’s disease.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first investigation of PVD incidence, as identified by a board certified otorhinolaryngologist in a primary care setting. We followed-up with the 393 patients for 633.0 days and identified 121 episodes of dizziness/vertigo. From those assessments, we were able to diagnose the 76 PVD patients (63.0%). In addition, we described the incidence of dizziness/vertigo and PVD: 194.7 per 1,000 person-years and 115.7 per 1,000 person-years, respectively. Our results differ significantly, in some ways, from those of previous studies.

The incidence of dizziness/vertigo in our study was higher than in previous studies. The Dutch National Survey of General Practice 2001 reported that the incidence of dizziness/vertigo was 47.1 per 1,000 person-years among patients aged 65 years or older who consulted their family physicians.Citation2 On the other hand, the 1-year incidence of dizziness/vertigo assessed through the German National Telephone Health Interview Survey 2003 was reported as being 1.4%.Citation18 This may have been due to the different backgrounds of the study populations or the differences in dizziness/vertigo measurements. In our study, the patients were treated as if they had lifestyle-related diseases, so we monitored their dizziness/vertigo more frequently than was done in previous studies. In addition, the patients who may have exhibited dizziness and vertigo because of antihypertensive drugs, diuretic and anxiolytic use are included.

The proportion of PVD (63.0%) among those who reported dizziness/vertigo in our study was slightly higher than in previous studies.Citation8,Citation14,Citation15 In previous reports, dizziness/vertigo was attributed to PVD in 221 out of 503 patients (44%) and 3,125 out of 9,472 patients (33%).Citation8,Citation15 This might be due to differences in the populations or PVD measurements. In our study, the participants’ ages (mean age: 65.5 years) were older than those in the abovementioned studies (mean ages: 58 and 52.9 years, respectively). However, the proportion of APV (80.2%) among the 76 PVD patients in our study was similar to the proportion of APV (71.6%) assessed by the study of emergency department visits in the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS).Citation32

The participants who complained of dizziness/vertigo were examined by a board certified otorhinolaryngologist in this study; therefore, PVD was detected more precisely. The risk of missing a diagnosis of PVD was reduced. This was one of our study’s main strengths. The other was that we followed-up all the participants. This led to a more accurate representation of the prevalence of dizziness/vertigo and PVD.

This study has two limitations. First, it was conducted at only one primary care clinic. Therefore, its results might not be generalizable to other primary care clinics in Japan. Another limitation is this study’s selection bias. The participants of this study had lifestyle-related diseases. If these are associated with PVD, the incidence found in our study might be inaccurately estimated as being higher than that in the general population. It is known that metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus are associated with vestibular dysfunction.Citation33,Citation34 We need to investigate the incidence of PVD among different primary care clinics and within the general population in future studies. We will also need to analyze the associations between lifestyle-related diseases and PVD.

Conclusion

We reported the incidence of dizziness/vertigo among Japanese primary care clinic patients, which was higher than that usually observed in the general population-based data. Furthermore, we described the incidence of PVD and found it to be a major cause of dizziness/vertigo.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HannafordPCSimpsonJABissetAFThe prevalence of ear, nose and throat problems in the community: results from a national cross-sectional postal survey in ScotlandFam Pract200522322723315772117

- MaarsinghORDrosJSchellevisFGDizziness reported by elderly patients in family practice: prevalence, incidence, and clinical characteristicsBMC Fam Pract201011220064231

- DuckittRPalssonRBosanskaLCommon diagnoses in internal medicine in Europe 2009: a pan-European, multi-centre surveyEur J Intern Med201021544945220816603

- TakeshimaTKumadaMMiseJReasons for encounter and diagnoses of new outpatients at a small community hospital in Japan: an observational studyInt J Gen Med2014725926924940078

- MoulinTSablotDVidryEImpact of emergency room neurologists on patient management and outcomeEur Neurol200350420721414634264

- SloanePDDizziness in primary care. Results from the National Ambulatory Medical Care SurveyJ Fam Pract198929133382738548

- PostREDickersonLMDizziness: a diagnostic approachAm Fam Physician201082436136820704166

- BirdJCBeynonGJPrevostATBaquleyDMAn analysis of referral patterns for dizziness in the primary care settingBr J Gen Pract1998484371828183210198501

- KroenkeKPriceRKSymptoms in the community. Prevalence, classification, and psychiatric comorbidityArch Intern Med19935321247424808215752

- JönssonRSixtELandahlSRosenhallUPrevalence of dizziness and vertigo in an urban elderly populationJ Vestib Res2004141475215156096

- KroenkeKHoffmanRMEinstadterDHow common are various causes of dizziness? A critical reviewSouth Med J200093216016710701780

- Newman-TokerDEHsiehYHCamargoCAJrSpectrum of dizziness visits to US emergency departments: cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sampleMayo Clin Proc200883776577518613993

- NakashimaKYokoyamaYShimoyamaRPrevalence of neurological disorders in a Japanese townNeuroepidemiology19961542082138817503

- NeuhauserHKRadtkeAvon BrevernMBurden of dizziness and vertigo in the communityArch Intern Med2008168192118212418955641

- AggarwalNTBennettDABieniasJLThe prevalence of dizziness and its association with functional disability in a biracial community populationJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci2000555M288M29210819319

- ThompsonTLAmedeeRVertigo: a review of common peripheral and central vestibular disordersOchsner J200991202621603405

- FroehlingDASilversteinMDMohrDNBeattyCWThe rational clinical examination. Does this dizzy patient have a serious form of vertigo?JAMA199427153853888283588

- NeuhauserHKvon BrevernMRadtkeAEpidemiology of vestibular vertigo: a neurotologic survey of the general populationNeurology200527;656898904

- XuWHangJGaoWAssociation between job stress and newly detected combined dyslipidemia among Chinese workers: findings from the SHISO studyJ Occup Health201153533434221817833

- AriyoshiKOkuyaSKunitsuguIUltrasound analysis of gray-scale median value of carotid plaques is a useful reference index for cerebro-cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetesJ Diabetes Invest2015619197

- TakaishiHTaniguchiTFujiokaYIshikawaYYokoyamaMImpact of increasing diabetes on coronary artery disease in the past decadeJ Atheroscler Thromb200411527127715557709

- TeramotoTSasakiJUeshimaHRisk factors of atherosclerotic diseases. Executive summary of Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) guideline for diagnosis and prevention of atherosclerosis cardiovascular diseases for JapaneseJ Atheroscler Thromb200714626727718176013

- LeeJSHayashiKMishraGIndependent association between age at natural menopause and hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus: Japan nurses’ health studyJ Atheroscler Thromb201320216116923079582

- SuzukiJKurosuTKonTTomaruTImpact of cardiovascular risk factors on progression of arteriosclerosis in younger patients: evaluation by carotid duplex ultrasonography and cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI)J Atheroscler Thromb201421655456224521982

- BisdorffAVon BrevernMLempertTNewman-TokerDEClassification of vestibular symptoms: towards an international classification of vestibular disordersJ Vestib Res2009191–211319893191

- FattoriBNacciAGhilardiPLAcute peripheral vertigo: involvement of the hemostatic systemInt Tinnitus J20039212412915106288

- StruppMArbusowVAcute vestibulopathyCurr Opin Neurol2001141112011176212

- FurmanJMCassSPBenign paroxysmal positional vertigoN Engl J Med1999341211590159610564690

- ParnesLSAgrawalSKAtlasJDiagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)CMAJ2003169768169314517129

- GacekRRA perspective on recurrent vertigoORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec20137529110723796949

- No authors listedCommittee on Hearing and Equilibrium guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of therapy in Menière’s disease. American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Foundation, IncOtolaryngol Head Neck Surg199511331811857675476

- Newman-TokerDECamargoCAJrHsiehYHPelletierAJEdlowJADisconnect between charted vestibular diagnoses and emergency department management decisions: a cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sampleAcad Emerg Med2009161097097719799573

- YamanakaTFukudaTShirotaSThe prevalence and characteristics of metabolic syndrome in patients with vertigoPLoS One2013812e8016

- AgrawalYCareyJPDella SantinaCCSchubertMCMinorLBDisorders of balance and vestibular function in US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001–2004Arch Intern Med20091691093894419468085