Abstract

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the most common gastrointestinal disorders worldwide. The economic impact of IBS on the health care system is substantial, as is the personal impact on patients. Patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D) comprise a substantial proportion of the overall IBS population. Primary care providers are often the first point of contact for patients with IBS-D and can accurately diagnose IBS after a careful history and examination without extensive diagnostic tests. Several pharmacologic treatments (eg, loperamide, alosetron, and antidepressants) and non-pharmacologic treatments (eg, dietary modification and probiotics) are available for IBS-D, but restrictions on use (eg, alosetron) or the lack of controlled trial data showing reductions in both global and individual IBS-D symptoms (eg, bloating, pain and stool frequency) emphasize the need for alternative treatment options. Two newer medications (eluxadoline and rifaximin) were approved in May 2015 for the treatment of IBS-D, and represent new treatment options for this common gastrointestinal condition.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a prevalent functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder that affects up to 15% of the general global population.Citation1–Citation5 IBS is characterized by symptoms of abdominal pain or discomfort that are relieved by defecation, and is associated with disordered bowel function (ie, constipation, diarrhea, or alternating constipation and diarrhea).Citation6 IBS can be diagnosed using Rome III criteria and subclassified according to patients’ predominant stool pattern using the Bristol Stool Form Scale as either constipation- or diarrhea-predominant, mixed type, or unsubtyped/unclassified (ie, insufficient abnormality of stool consistency to meet criteria for the other IBS subtypes; ).Citation6 Up to 40% of patients with IBS have diarrhea as the predominant bowel symptom (IBS-D subtype).Citation1

Table 1 Diagnostic criteria for IBSTable Footnote*

IBS significantly reduces the quality of life of patients, their partners, and caregivers and impairs daily functioning.Citation3,Citation7 It places a substantial financial burden on society, owing to impaired work productivity and increased use of health care resources.Citation3 At least some of the increased costs are related to additional medical tests and medical and non-medical therapies, which are of uncertain value.Citation4 In a database search of patients with and without IBS, patients with IBS were more likely to undergo standard laboratory blood and stool testing and endoscopic testing than other patients.Citation8

Because the majority of IBS diagnoses originate from primary care physicians (PCPs),Citation8 PCPs are in a unique position to facilitate proper diagnosis and management techniques that may reduce the overall personal and societal burden of IBS. Diagnosis and management of IBS by PCPs varies substantially throughout the United States and is inconsistently applied across all patient age groups.Citation9 Patient misinformation concerning the proper diagnosis of IBS may result in PCPs performing extensive diagnostic testing to provide reassurance;Citation10 however, there is little evidence that such additional testing alters the final diagnosis.Citation11 Facilitating understanding and effective communication of diagnosing IBS among PCPs and patients may solidify standard of care practices, thereby eliminating extraneous tests and reducing health care costs.

This article provides an overview of the pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying IBS-D, discusses IBS-D diagnosis, and highlights newer treatment advances for patients with IBS-D.

Pathophysiology of IBS-D

Dietary factors

Ingestion of a meal stimulates a complex set of reactions that allow processing, absorption, and movement of the ingested food through the GI tract.Citation12 These processes are coordinated via bidirectional neural, hormonal, and immunologic communication between the GI tract and the brain.Citation13 The possible relationship between diet and IBS is ill defined, but diet-induced alterations in the gut microbiota, permeability, and proinflammatory responses (either directly via food sensitivity/intolerance or indirectly via changes in microbiota composition) have been proposed and may contribute to the increased visceral hypersensitivity and disruption in brain-GI tract crosstalk associated with IBS.Citation14

Accelerated transit

The GI tract is controlled, in part, by the enteric nervous system (ENS), which uses neurotransmitters (eg, serotonin; also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine) to modulate motility, mucosal secretion and absorption activities, mucosal homeostasis, blood flow, and immune function.Citation15 Serotonin receptors are located throughout the ENS and are involved in the regulation of reflexes that control GI motility and secretion, as well as visceral sensation.Citation16 Disruptions in serotonin signaling, including a greater number of serotonin-positive enterochromaffin cells in the crypt epithelium, increased spontaneous release of serotonin from descending colon mucosal cells, decreased concentration of colonic serotonin, and diminished expression of serotonin reuptake transporters, have been described in patients with IBS-D.Citation17,Citation18 An increased number of brief (<15 seconds) colonic contractions, accelerated colonic transit, and alterations in small bowel motor function (eg, increased frequency of migrating motor complexes, duodenal and jejunal contractions, and ileal distension) have been observed in patients with IBS-D;Citation19–Citation21 however, whether these disruptions are a direct result of alterations in serotonin signaling or a consequence of other pathophysiologic processes is unclear.

Visceral hypersensitivity

Some patients with IBS have reduced thresholds for the sensation of bloating throughout the GI system compared with unaffected individuals; however, visceral perception is not altered in all patients and does not necessarily correlate with a particular symptom profile.Citation22 Sensitization of neurons involved in the perception or transmission of sensory information from the ENS to the central nervous system (CNS) is likely involved in IBS-related visceral hypersensitivity.Citation15 Alterations in sensory neuromediators (eg, inflammatory mediators) that occur as a result of changes in gut microbiota, which might also be associated with a previous episode of gastroenteritis,Citation19 may contribute to the visceral hypersensitivity and abdominal pain observed in some patients with IBS-D.Citation23 Studies have also implicated alterations in CNS innervation and processing of GI tract stimulation in patients with IBS compared with healthy controls.Citation15,Citation24,Citation25 In patients with IBS-D, increased visceral activity has been associated with an increased number of colonic mast cells, closer proximity of mast cells to nerves, and augmented activation of pain and motor areas in the brain.Citation24,Citation26 Taken together, these data suggest that a variety of factors contribute to enhanced GI tract reactivity in patients with IBS-D.

Gut microbiota

The gut microbiota is responsible for a variety of structural, metabolic, and immune functionsCitation27 and is relatively stable in healthy individuals.Citation28–Citation30 Because of the plethora of functions of the gut microbiota in human health, its disruption (ie, dysbiosis) causes aberrations in multiple interconnected pathways, including brain-gut crosstalk, regulation of the neuroendocrine system, and immune system homeostasis, and may contribute to the symptoms of IBS-D. Several lines of evidence support a role of the gut microbiota in the pathophysiology of IBS-D. For example, patients who experience gastroenteritis are more likely to develop IBS (ie, postinfectious IBS), including the IBS-D subtype, than patients without a history of gastroenteritis.Citation31 In addition, the composition and diversity of the gut microbiota in patients with IBS-D is altered compared with that in healthy individuals and patients with other IBS subtypes.Citation32–Citation35 Additional clinical studies are needed to fully understand the consequences of the gut microbiota dysbiosis associated with IBS-D, but the efficacy of agents that may impact the gut microbiota (eg, probiotics and non-systemic antibiotics) suggest at least a symptomatic role.

Diagnosis of IBS-D

Patients with IBS-D typically present with abdominal pain associated with frequent loose stools and cramping, urgency that is not relieved by defecation, and mucus in the stool.Citation36 The occurrence of additional comorbid functional GI and extraintestinal symptoms or disorders (eg, gastroesophageal reflux disease,Citation37 dyspepsia,Citation38 interstitial cystitis,Citation39 migraine headaches,Citation38 and fibromyalgiaCitation39) may increase the probability of a positive IBS diagnosis. Symptoms may be mild and infrequent, moderate and somewhat bothersome, or severe enough to interfere with daily functioning, but all typically require an ongoing management strategy to control symptoms.Citation40,Citation41

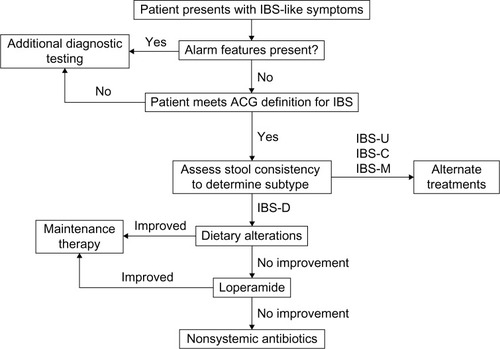

The diagnosis of IBS is often first made by PCPs, particularly by internists and family practitioners, and usually without the need for specialized tests (eg, endoscopic or radiologic tests).Citation8 The diagnosis may be established via a symptom-based strategy using a combination of patient history, exclusion of alarm symptoms/warning signs, and use of the Rome III criteria ()Citation36 or the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) definition of IBS (ie, abdominal pain or discomfort that occurs in association with altered bowel habits for ≥3 months).Citation42–Citation44 Diagnostic testing for celiac disease may be warranted in patients presenting with diarrhea as their predominant symptom, but extensive diagnostic testing is unnecessary for patients without alarm symptoms. PCPs and other non-IBS specialists tend to perform a greater number of diagnostic tests before informing the patient of an IBS diagnosis;Citation45 however, at present, there appears to be little diagnostic value in some of these tests (eg, complete blood count, C-reactive protein, serum chemistries, stool testing for intestinal parasites, and sigmoidoscopy with biopsies).Citation36,Citation46 Addressing disease-related concerns, discussing reasonable treatment goals and expectations, educating and empowering patients, and addressing somatization issues with patients may provide greater benefit than extensive testing.Citation45

Table 2 Differential diagnosis in patients presenting with symptoms of IBS and alarm symptoms/warning signs

Treatment options for IBS-D

Antimotility agents

Loperamide

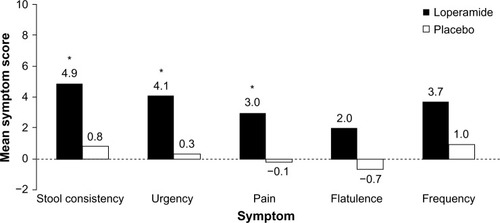

Loperamide is an over-the-counter opioid receptor agonist that reduces peristalsis, increases intestinal transit time, and diminishes loss of fluid and electrolytes. In four randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind studies, patients with IBS-D who received loperamide experienced a significant improvement in individual symptoms of stool frequency,Citation47,Citation48 stool consistency/number of unformed stools,Citation47–Citation50 and urgencyCitation47 but no improvement in bloating, a frequently bothersome IBS symptom ().Citation48,Citation49 Abdominal pain, a cardinal symptom of IBS, was not relieved with the use of loperamide compared with placebo in most studies.Citation47,Citation48,Citation50 Loperamide was well tolerated by patients with IBS-D;Citation47–Citation49 the only adverse effects reported were constipation, swollen fingers, trouble sleeping, and oral blisters (n=1 each).Citation47,Citation49 Loperamide 2 mg/day to 8 mg/day may be useful in some patients with IBS-D, but it is not currently recommended by the ACG because of a lack of high-quality evidence.Citation4

Figure 1 Symptom improvement with loperamide.

Abbreviation: IBS-D, diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome.

Eluxadoline

Eluxadoline, a mixed μ-opioid receptor agonist and δ-opioid receptor antagonist that reduces contractility and secretion in the GI tract, was approved in 2015 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for daily administration in patients with IBS-D.Citation51 However, because the FDA has recommended to the US Drug Enforcement Administration that eluxadoline be classified as a controlled substance and the designation is pending, eluxadoline is not anticipated to be available until the first quarter of 2016. In two separate Phase 3 trials in patients with IBS-D (pooled population, >2,400 patients), currently only published in abstract form, eluxadoline 75 mg or 100 mg twice daily significantly improved abdominal pain and stool consistency (P<0.005 vs placebo), number of daily bowel movements (P<0.05), and urgency (P<0.05).Citation52 These benefits were observed in the overall population and in patients for whom loperamide had provided insufficient relief.Citation9 The most commonly reported adverse events (AEs) were constipation (7.4% and 8.3% for 75 mg and 100 mg eluxadoline, respectively, compared with 2.4% for placebo) and nausea (7.8% and 7.3% for 75 mg and 100 mg eluxadoline, respectively, compared with 4.8% for placebo).Citation52

Probiotics

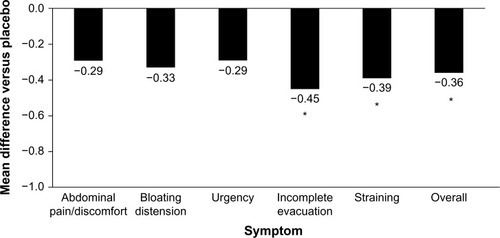

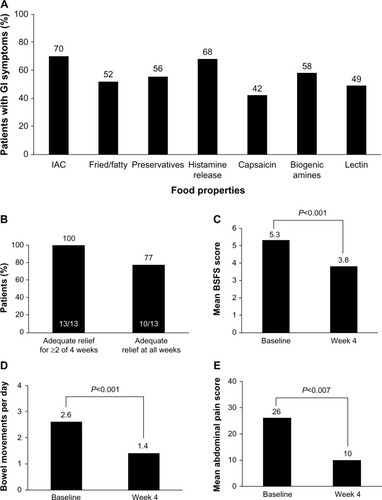

Although probiotics may be an intuitive treatment option for the treatment of IBS-D, few have been studied clinically. In addition, the quality and consistency of probiotic preparations on store shelves is questionable because of shelf-life limitations and a lack of government-sanctioned quality-control standards. The limited clinical trial data published for probiotics in IBS-D are contradictory and strain-dependent. In a double-blind, placebo controlled study, VSL#3® (Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) for 8 weeks did not improve small bowel or colonic transit and had no effect on bowel dysfunction, abdominal pain, flatulence, or urgency compared with placebo in patients with IBS-D (n=25).Citation53 In contrast, in a subset of patients with IBS-D, treatment with Bifidobacterium infantis 1×108 cfu/mL capsule once daily for 4 weeks (n=49) significantly improved incomplete evacuation (P=0.008), straining (P=0.007), bowel habit satisfaction (P=0.014), and overall IBS symptoms (P=0.028) vs placebo (n=56; ).Citation54 Based on these limited data and the favorable benefit/risk ratio, B. infantis 1×108 cfu/mL may alleviate symptoms in some patients; however, health care providers should be aware of the small sample size of the trials and the limited number of results available compared with those of other currently available agents. In addition, health care providers should weigh the potential benefits against the cost to the patients.Citation4

Figure 2 Reduction of IBS symptoms with Bifidobacterium infantis capsule administered once daily vs placebo.

Abbreviations: IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-D, diarrhea-predominant IBS.

Dietary modification

Many patients with IBS report the onset of GI symptoms after ingestion of specific food types (eg, fried or fatty foods; ).Citation55 Rigorous trials of dietary manipulations in patients with IBS are lacking; however, potential benefits have been observed with some dietary modifications.Citation4,Citation56 A diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) may decrease symptoms in patients with IBS,Citation57–Citation59 particularly those with IBS-D.Citation57 In addition, two small trials of a gluten-free or very low carbohydrate diet showed improved stool frequency,Citation60,Citation61 stool consistency,Citation60 and abdominal painCitation60 in patients with IBS-D ().Citation60 Given the lack of strong evidence for dietary adjustment and the high patient adherence requirements, dietary modification plans are not strongly recommended by the ACG.Citation4

Figure 3 Percentage of patients reporting GI symptoms.

Abbreviations: BSFS, Bristol Stool Form Scale; GI, gastrointestinal; IAC, incompletely absorbed carbohydrates; IBS-D, diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome.

Serotonergic agents

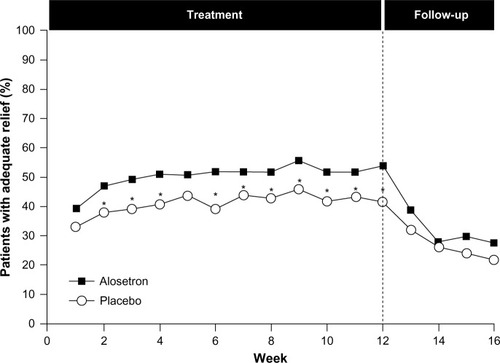

Given the complex role of serotonin in the GI tract, serotonin antagonists have been evaluated for the treatment of IBS-D; however, only alosetron, a serotonin receptor antagonist, is available, under a risk management program, in the United States.Citation4 A number of randomized, placebo-controlled trials have been conducted with alosetron in patients with IBS, including those with the IBS-D subtype. Most of these trials showed improvement in stool consistency, stool frequency, and overall IBS symptoms in females during treatment; however, daily therapy is required, and effects diminish rapidly with treatment cessation ().Citation62–Citation67 Evidence on the efficacy of alosetron in males has been conflicting; early dose-ranging studies showed a lack of consistent efficacy in males despite beneficial effects in females.Citation65,Citation67 However, in a 2005 trial, alosetron treatment resulted in an increased percentage of males with adequate relief of pain and discomfort and improved stool consistency, despite a lack of effect on stool frequency, urgency, incomplete evacuation, or bloating.Citation68

Figure 4 Efficacy of alosetron in females with severe IBS-D.

Abbreviations: IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; IBS-D, diarrhea-predominant IBS.

Alosetron is associated with several AEs, predominately constipation.Citation69 In 2001, alosetron was voluntarily withdrawn from the US market because of concerns of reports of ischemic colitis,Citation70 which occurs in approximately 0.1% of patients.Citation71 It was reintroduced into the US market in 2002 but only for females with severe IBS-D and with required participation in a risk-management program.Citation4

Antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) modulate the activity of serotonin in the GI tract and reduce global IBS symptoms and abdominal pain in patients with IBS (number need to treat =4 for both agents).Citation4 Because tricyclic antidepressants increase intestinal transit time, they may be preferable to SSRIs for the treatment of patients with IBS-D.Citation72 However, data on the efficacy of these agents specifically for IBS-D are limited. A small trial of amitriptyline in patients with IBS-D (n=50) reported improvement in the feeling of incomplete defecation and loose stools compared with placebo.Citation73 AEs (eg, drowsiness and dry mouth) are more common with anti-depressants than placebo (number needed to harm =9) and may limit patient tolerability. Currently, the ACG does not strongly recommend antidepressants for IBS-D and notes the potential for AEs, the greater costs of some medications (especially SSRIs), and potential patient reluctance to take antidepressants.Citation4

Fecal microbiota transplant

The recognition of the importance of gut microflora modulation in IBS has prompted the investigation of a non-traditional means of restoring the gut microbiota (ie, fecal microbiota transplant [FMT]). FMT involves the administration of healthy donor stool into the colon of the symptomatic patients.Citation74 Benefits of this therapy have been described for other GI diseases associated with alterations in the gut microbiota (eg, Clostridium difficile infection and inflammatory bowel disease);Citation74 however, there are few published data on the efficacy of this therapy in patients with IBS-D (n=9).Citation75 Therefore, FMT should be considered as an investigational therapy because its usefulness as a therapeutic option for IBS-D is unknown. In addition, there are notable safety concerns with FMT, including transient GI complaints (eg, abdominal cramping) and the potential for development of autoimmune disorders.

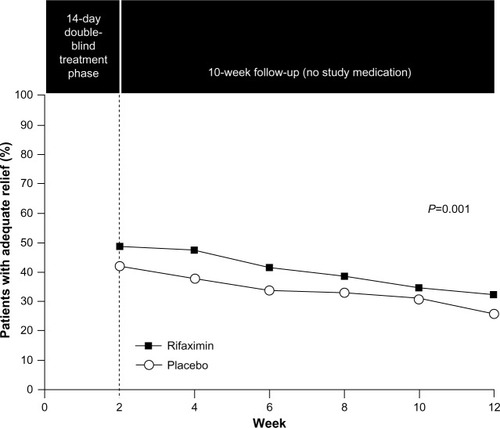

Non-systemic antibiotics (rifaximin)

The role of the gut microbiota in IBS, including interactions with CNS processes (eg, pain sensitivity), suggests that modulation of the gut microbiota might improve IBS symptoms. Rifaximin, a non-systemic antibiotic, was approved in May 2015 for the treatment of IBS-D in adults. In a combined analysis of two separate Phase 3 trials, a 14-day course of rifaximin 550 mg three times daily, in patients with IBS-D, significantly increased the percentage of patients who had adequate relief of global IBS symptoms (P<0.001; pooled; ),Citation76 and improved IBS-related bloating (P<0.001; pooled) and abdominal pain/discomfort and loose or watery stools (P=0.008; pooled) compared with placebo for up to 10 weeks post-treatment.Citation76 In a Phase 3 retreatment study of patients initially responding to open-label rifaximin who experienced symptom recurrence, the percentage of responders (pain and stool consistency improvements) to randomized, repeat treatment was significantly greater with rifaximin vs placebo (33% vs 25%, P=0.02).Citation77 The AE profile of rifaximin in patients with IBS-D was generally similar to that observed with placebo. AEs (≥2% of patients) reported more often with rifaximin vs placebo were nausea (4.3% vs 3.8%), diarrhea (4.3% vs 3.5%), sinusitis (2.7% vs 2.5%), vomiting (2.4% vs 1.4%), and cough (2.1% vs 1.4%).Citation76 Data suggest that 1 patient would experience an AE with rifaximin for every 846 patients who would benefit (number needed to harm =8,971 and number needed to treat =10.6).Citation76,Citation78,Citation79 As noted in the Warnings and Precautions section of the rifaximin prescribing information, there is a risk of C. difficile infection with use of nearly all antibacterial agents including rifaximin, and severity may vary from symptoms of mild diarrhea to fatal colitis. Based on its favorable efficacy and safety profiles, rifaximin is a viable treatment option for patients with IBS-D; however, health care providers should be aware that response may not be ubiquitous.Citation4

Figure 5 Efficacy of rifaximin for patients with IBS-D.

Abbreviation: IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

Conclusion

IBS-D is a common GI condition that imposes substantial personal and societal burdens. Whereas the etiology and pathophysiology of IBS-D continue to be investigated, interconnected alterations in visceral sensitivity, GI motility, and gut microbiota likely play a role in the disorder. PCPs are often the first point of contact for patients with IBS-D and are capable of identifying and treating IBS-D. The diagnosis and treatment of IBS-D should involve a symptom-based strategy consisting of exclusion of alarm signs, evaluation of IBS subtype, and selection of treatment based on risk/benefit profile (). Extensive diagnostic testing in the absence of alarm symptoms is unnecessary and should be avoided to minimize costs as appropriate. Several treatment options are available for IBS-D; however, some therapies (eg, diet modulation and probiotics) require additional clinical safety and efficacy data and therefore have not been strongly recommended. Two drugs approved in the United States in May 2015 for IBS-D (eluxadoline and rifaximin) appear to be efficacious and well-tolerated treatment alternatives.

Author contribution

The author contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

Technical editorial and medical writing support was provided, under the direction of the author, by Mary Beth Moncrief, PhD, and Jillian Gee, PhD, Synchrony Medical Communications, LLC, West Chester, PA. Funding for this support was provided by Salix, a Division of Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC, Bridgewater, NJ, USA. The author was not provided funding for development of this review.

Disclosure

Dr Lacy is a co-investigator for the NIH Functional Dyspepsia Treatment Trial and has served on the scientific advisory boards of Ironwood, Takeda, and Prometheus.

References

- LovellRMFordACGlobal prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysisClin Gastroenterol Hepatol201210771272122426087

- WilsonSRobertsLRoalfeABridgePSinghSPrevalence of irritable bowel syndrome: a community surveyBr J Gen Pract20045450449550215239910

- HunginAPSChangLLockeGRDennisEHBarghoutVIrritable bowel syndrome in the United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impactAliment Pharmacol Ther200521111365137515932367

- FordACMoayyediPLacyBEAmerican College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipationAm J Gastroenterol2014109Suppl 1S2S2625091148

- NgKSNassarNHamdKNagarajahAGladmanMAPrevalence of functional bowel disorders and faecal incontinence: an Australian primary care surveyColorectal Dis201517215015925359460

- LongstrethGFThompsonWGCheyWDHoughtonLAMearinFSpillerRCFunctional bowel disordersGastroenterology200613051480149116678561

- WongRKDrossmanDAWeinlandSRPartner burden in irritable bowel syndromeClin Gastroenterol Hepatol201311215115522858730

- LadabaumUBoydEZhaoWKDiagnosis, comorbidities, and management of irritable bowel syndrome in patients in a large health maintenance organizationClin Gastroenterol Hepatol2012101374521871250

- LacyBPatelHGuérinARegional variation of care for irritable bowel syndrome in the United StatesAm J Gastroenterol2014109Suppl 2S529

- LacyBEWeiserKNoddinLIrritable bowel syndrome: patients’ attitudes, concerns and level of knowledgeAliment Pharmacol Ther200725111329134117509101

- CashBDSchoenfeldPCheyWDThe utility of diagnostic tests in irritable bowel syndrome patients: a systematic reviewAm J Gastroenterol200297112812281912425553

- CuomoRAndreozziPZitoFPPassanantiVDe CarloGSarnelliGIrritable bowel syndrome and food interactionWorld J Gastroenterol201420278837884525083057

- HayesPAFraherMHQuigleyEMIrritable bowel syndrome: the role of food in pathogenesis and managementGastroenterol Hepatol (NY)2014103164174

- RingelYMaharshakNIntestinal microbiota and immune function in the pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndromeAm J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol20133058G529G54123886861

- VermeulenWDe ManJGPelckmansPADe WinterBYNeuroanatomy of lower gastrointestinal pain disordersWorld J Gastroenterol20142041005102024574773

- CrowellMDRole of serotonin in the pathophysiology of the irritable bowel syndromeBr J Pharmacol200414181285129315100164

- CoatesMDMahoneyCRLindenDRMolecular defects in mucosal serotonin content and decreased serotonin reuptake transporter in ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel syndromeGastroenterology200412671657166415188158

- CremonCCariniGWangBIntestinal serotonin release, sensory neuron activation, and abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndromeAm J Gastroenterol201110671290129821427712

- SpillerRAzizQCreedFGuidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical managementGut200756121770179817488783

- WhiteheadWEEngelBTSchusterMMIrritable bowel syndrome: physiological and psychological differences between diarrhea-predominant and constipation-predominant patientsDig Dis Sci19802564044137379673

- ManabeNWongBSCamilleriMBurtonDMcKinzieSZinsmeisterARLower functional gastrointestinal disorders: evidence of abnormal colonic transit in a 287 patient cohortNeurogastroenterol Motil2010223293e28220025692

- PosserudIErsrydASimrénMFunctional findings in irritable bowel syndromeWorld J Gastroenterol200612182830283816718806

- ThabaneMSimunovicMAkhtar-DaneshNGargAXClarkWFMarshallJKClustering and stability of functional lower gastrointestinal symptom after enteric infectionNeurogastroenterol Motil2012246546552e25222356614

- Wilder-SmithCHSchindlerDLovbladKRedmondSMNirkkoABrain functional magnetic resonance imaging of rectal pain and activation of endogenous inhibitory mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome patient subgroups and healthy controlsGut200453111595160115479679

- LarssonMBTillischKCraigADBrain responses to visceral stimuli reflect visceral sensitivity thresholds in patients with irritable bowel syndromeGastroenterology2012142346347222108191

- BarbaraGStanghelliniVDe GiorgioRActivated mast cells in proximity to colonic nerves correlate with abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndromeGastroenterology2004126369370214988823

- SekirovIRussellSLAntunesLCFinlayBBGut microbiota in health and diseasePhysiol Rev201090385990420664075

- MartínezIMullerCEWalterJLong-term temporal analysis of the human fecal microbiota revealed a stable core of dominant bacterial speciesPLoS One201387e6962123874976

- KajanderKMyllyluomaERajilic-StojanovicMClinical trial: multispecies probiotic supplementation alleviates the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome and stabilizes intestinal microbiotaAliment Pharmacol Ther2008271485717919270

- VanhoutteTHuysGDe BrandtESwingsJTemporal stability analysis of the microbiota in human feces by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis using universal and group-specific 16S rRNA gene primersFEMS Microbiol Ecol200448343744619712312

- CremonCStanghelliniVPallottiFSalmonella gastroenteritis during childhood is a risk factor for irritable bowel syndrome in adulthoodGastroenterology20141471697724657623

- Jalanka-TuovinenJSalojärviJSalonenAFaecal microbiota composition and host-microbe cross-talk following gastroenteritis and in postinfectious irritable bowel syndromeGut201463111737174524310267

- LyraARinttiläTNikkiläJDiarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome distinguishable by 16S rRNA gene phylotype quantificationWorld J Gastroenterol200915475936594520014457

- MalinenERinttiläTKajanderKAnalysis of the fecal microbiota of irritable bowel syndrome patients and healthy controls with real-time PCRAm J Gastroenterol2005100237338215667495

- CarrollIMRingel-KulkaTSiddleJPRingelYAlterations in composition and diversity of the intestinal microbiota in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeNeurogastroenterol Motil201224652153022339879

- WilkinsTPepitoneCAlexBSchadeRRDiagnosis and management of IBS in adultsAm Fam Physician201286541942622963061

- YarandiSSNasseri-MoghaddamSMostajabiPMalekzadehROverlapping gastroesophageal reflux disease and irritable bowel syndrome: increased dysfunctional symptomsWorld J Gastroenterol201016101232123820222167

- FaresjoAGrodzinskyEHallertCTimpkaTPatients with irritable bowel syndrome are more burdened by comorbidity and worry about serious diseases than healthy controls – eight years follow-up of IBS patients in primary careBMC Public Health20131383224025070

- WhiteheadWEPalssonOJonesKRSystematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications?Gastroenterology200212241140115611910364

- SaitoYASchoenfeldPLockeGRIIIThe epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in North America: a systematic reviewAm J Gastroenterol20029781910191512190153

- EngsbroALSimrenMBytzerPShort-term stability of subtypes in the irritable bowel syndrome: prospective evaluation using the Rome III classificationAliment Pharmacol Ther201235335035922176384

- OldenKWDiagnosis of irritable bowel syndromeGastroenterology200212261701171412016433

- EngsbroALBegtrupLMKjeldsenJPatients suspected of irritable bowel syndrome-cross-sectional study exploring the sensitivity of Rome III criteria in primary careAm J Gastroenterol2013108697298023419383

- BrandtLJCheyWDFoxx-OrensteinAEAn evidence-based systematic review on the management of irritable bowel syndromeAm J Gastroenterol2009104Suppl 1S8S28

- SpiegelBMFaridMEsrailianETalleyJChangLIs irritable bowel syndrome a diagnosis of exclusion?: a survey of primary care providers, gastroenterologists, and IBS expertsAm J Gastroenterol2010105484885820197761

- BegtrupLMEngsbroALKjeldsenJA positive diagnostic strategy is noninferior to a strategy of exclusion for patients with irritable bowel syndromeClin Gastroenterol Hepatol201311895696223357491

- CannPAReadNWHoldsworthCDBarendsDRole of loperamide and placebo in management of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)Dig Dis Sci19842932392476365490

- HovdenakNLoperamide treatment of the irritable bowel syndromeScand J Gastroenterol Suppl198713081843306904

- LavöBStenstamMNielsenALLoperamide in treatment of irritable bowel syndrome – a double-blind placebo controlled studyScand J Gastroenterol Suppl198713077803306903

- EfskindPSBernklevTVatnMHA double-blind placebo-controlled trial with loperamide in irritable bowel syndromeScand J Gastroenterol19963154634688734343

- DoveLSLemboARandallCWEluxadoline benefits patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea in a phase 2 studyGastroenterology2013145232933823583433

- LemboADoveSAndraeDEluxadoline for the treatment of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: results of 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trials of efficacy and safetyGastroenterology2014146Suppl 1, issue 5S159

- KimHJCamilleriMMcKinzieSA randomized controlled trial of a probiotic, VSL#3, on gut transit and symptoms in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeAliment Pharmacol Ther200317789590412656692

- WhorwellPJAltringerLMorelJEfficacy of an encapsulated probiotic Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 in women with irritable bowel syndromeAm J Gastroenterol200610171581159016863564

- BöhnLStörsrudSTörnblomHBengtssonUSimrénMSelf-reported food-related gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS are common and associated with more severe symptoms and reduced quality of lifeAm J Gastroenterol2013108563464123644955

- LacyBEThe science, evidence and practice of dietary interventions in irritable bowel syndromeClin Gastroenterol Hepatol201513111899190625769411

- HalmosEPPowerVAShepherdSJGibsonPRMuirJGA diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndromeGastroenterology20141461677524076059

- de RoestRHDobbsBRChapmanBAThe low FODMAP diet improves gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective studyInt J Clin Pract201367989590323701141

- StaudacherHMLomerMCAndersonJLFermentable carbohydrate restriction reduces luminal bifidobacteria and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndromeJ Nutr201214281510151822739368

- AustinGLDaltonCBHuYA very low-carbohydrate diet improves symptoms and quality of life in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20097670670819281859

- Vazquez-RoqueMICamilleriMSmyrkTA controlled trial of gluten-free diet in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea: effects on bowel frequency and intestinal functionGastroenterology2013144590391123357715

- CamilleriMNorthcuttARKongSDukesGEMcSorleyDMangelAWEfficacy and safety of alosetron in women with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised, placebo-controlled trialLancet200035592091035104010744088

- KrauseRAmeenVGordonSHA randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess efficacy and safety of 0.5 mg and 1 mg alosetron in women with severe diarrhea-predominant IBSAm J Gastroenterol200710281709171917509028

- LemboTWrightRABagbyBAlosetron controls bowel urgency and provides global symptom improvement in women with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeAm J Gastroenterol20019692662267011569692

- CamilleriMMayerEADrossmanDAImprovement in pain and bowel function in female irritable bowel patients with alosetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonistAliment Pharmacol Ther19991391149115910468696

- CamilleriMCheyWYMayerEAA randomized controlled clinical trial of the serotonin type 3 receptor antagonist alosetron in women with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeArch Intern Med2001161141733174011485506

- BardhanKDBodemarGGeldofHA double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled dose-ranging study to evaluate the efficacy of alosetron in the treatment of irritable bowel syndromeAliment Pharmacol Ther2000141233410632642

- ChangLAmeenVZDukesGEMcSorleyDJCarterEGMayerEAA dose-ranging, phase II study of the efficacy and safety of alosetron in men with diarrhea-predominant IBSAm J Gastroenterol2005100111512315654790

- RahimiRNikfarSAbdollahiMEfficacy and tolerability of alosetron for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in women and men: a meta-analysis of eight randomized, placebo-controlled, 12-week trialsClin Ther200830588490118555935

- TongKNicandroJPShringarpureRChuangEChangLA 9-year evaluation of temporal trends in alosetron postmarketing safety under the risk management programTherap Adv Gastroenterol201365344357

- HeadingRBardhanKHollerbachSLanasAFisherGSystematic review: the safety and tolerability of pharmacological agents for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome – a European perspectiveAliment Pharmacol Ther200624220723616842449

- OldenKWTargeted therapies for diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeClin Exp Gastroenterol201256910022754282

- VahediHMeratSMomtahenSClinical trial: the effect of amitriptyline in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndromeAliment Pharmacol Ther200827867868418248658

- AroniadisOCBrandtLJIntestinal microbiota and the efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation in gastrointestinal diseaseGastroenterol Hepatol (NY)2014104230237

- PinnDMAroniadisOCBrandtLJIs fecal microbiota transplantation the answer for irritable bowel syndrome? A single-center experienceAm J Gastroenterol2014109111831183225373585

- PimentelMLemboACheyWDRifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipationN Engl J Med20113641223221208106

- LemboAPimentelMRaoSSEfficacy and safety of repeat treatment with rifaximin for diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D): results of the TARGET 3 studyPresented at: American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2014 Annual Scientific MeetingOctober 17–22 2014Philadelphia, PA

- ShahEKimSChongKLemboAPimentelMEvaluation of harm in the pharmacotherapy of irritable bowel syndromeAm J Med2012125438139322444104

- SchoenfeldPPimentelMChangLSafety and tolerability of rifaximin for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome without constipation: a pooled analysis of randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialsAliment Pharmacol Ther201439101161116824697851