Abstract

Background

Misdiagnosis, either over- or underdiagnosis, exposes older patients to increased risk of inappropriate or omitted investigations and treatments, psychological distress, and financial burden.

Objective

To evaluate the frequency and nature of diagnostic errors in 16 conditions prevalent in older patients by undertaking a systematic literature review.

Data sources and study selection

Cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, or systematic reviews of such studies published in Medline between September 1993 and May 2014 were searched using key search terms of “diagnostic error”, “misdiagnosis”, “accuracy”, “validity”, or “diagnosis” and terms relating to each disease.

Data synthesis

A total of 938 articles were retrieved. Diagnostic error rates of >10% for both over- and underdiagnosis were seen in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, heart failure, stroke/transient ischemic attack, and acute myocardial infarction. Diabetes was overdiagnosed in <5% of cases.

Conclusion

Over- and underdiagnosis are common in older patients. Explanations for over-diagnosis include subjective diagnostic criteria and the use of criteria not validated in older patients. Underdiagnosis was associated with long preclinical phases of disease or lack of sensitive diagnostic criteria. Factors that predispose to misdiagnosis in older patients must be emphasized in education and clinical guidelines.

Background

Accurate diagnosis is critical in older people (defined here as persons aged ≥65 years) to avoid unnecessary investigations and treatments and their associated costs and harm.Citation1 Diagnostic errors are relatively common when compared with other types of errors relating to medications and surgical procedures.Citation2–Citation4 Many older patients have more comorbidities requiring diagnosis, meaning they may be more susceptible to misdiagnosis.Citation5 Misdiagnosis not only endangers the health of older patients but also incurs opportunity costs for health care systems due to misused clinical interventions and care of iatrogenic illness.Citation5–Citation7

Older populations may be more vulnerable to diagnostic error for reasons that relate to both patient and clinician.Citation8 Older persons may attribute symptoms to normal aging, and not report them, and doctors may focus unduly on clinical clues suggesting particular diseases while discounting opposing clues.Citation9 Commonly used diagnostic criteria for specific diseases derived and validated in younger populations may not apply to older individuals.Citation6,Citation10

We undertook a systematic review to determine rates of over- and underdiagnosis of several diseases commonly encountered in older populations and to identify associated predisposing factors.

Data sources and study selection

Sixteen conditions were initially considered for inclusion in this review based on their reported prevalence and level of disease burden in older patients.Citation11,Citation12 These comprised dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart failure (HF), Parkinson’s disease (PD), stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), diabetes, osteoarthritis (OA), obstructive sleep apnea, peripheral arterial disease (PAD), gastroesophageal reflux disorder (GERD), epilepsy, hypertension (HTN), major depression, osteoporosis, and renal insufficiency.

Literature searches were undertaken by an author (TS) in July 2011 and repeated in September 2013 and May 2014 to ensure inclusion of newly published articles. The initial search gathered cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, or systematic reviews of studies assessing diagnostic errors, irrespective of disease or age, published in Medline in the last 20 years. The search used key search terms relating to diagnostic error, misdiagnosis, accuracy, or validity of diagnosis as well as MeSH search terms in both English and American formats. This group of articles was then searched for literature relating to the 16 target conditions using keywords and MeSH terms relevant to the conditions (). Retrieved studies’ reference lists were also examined for further articles addressing misdiagnosis in older patients.

Table 1 Search strategy and results (May 2014)

Selected studies were those published in English, in which ≥50% of study participants were aged ≥65 years and in which quantitative data on diagnostic rates, as measured using reference standards, could be obtained directly from the published study or by contact with study authors. Where articles did not report data specific to older cohorts, authors were contacted with a request for a subset of data including only subjects ≥65 years of age. Study selection and data collection were undertaken by one author (TS) and confirmed independently by the two remaining authors in joint discussion.

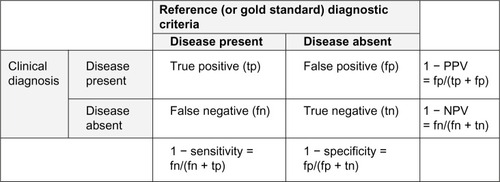

Overdiagnosis was measured using 1 – specificity (1–Sp) and 1 – positive predictive value (1–PPV), while under-diagnosis was measured using 1–sensitivity (1–Sn) or 1 – negative predictive value (1–NPV) (). Misdiagnosis was considered clinically significant when any of these values was ≥10%. The methodological quality of each study was evaluated for risk of bias and applicability using the quality assessment tool for diagnostic accuracy (QUADAS-2) (Supplementary materials), with those studies displaying higher quality given more emphasis in the qualitative reviews of each condition.

Data synthesis

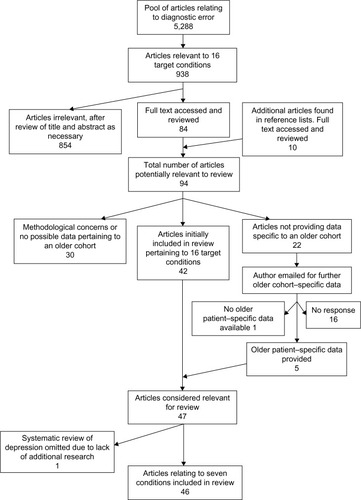

The final search for articles relating to diagnostic error in May 2014 yielded 5,288 titles with abstracts. This pool contained 938 articles pertaining to the 16 target conditions. On reviewing article abstracts, 84 assessed diagnostic validity and were considered relevant to this review. Perusal of bibliographies uncovered a further ten articles, totaling 94 reports for which full-text versions were retrieved. Of these, 22 did not report separate data for older patients, and enquiries were made to corresponding authors, of whom five provided data specific for older patients before expiry of a 2-week deadline.

Sleep disorders, OA, PAD, GERD, epilepsy, HTN, osteoporosis, and renal insufficiency were removed from the list of conditions due to the absence of any studies examining diagnostic accuracy in older patients that met our selection criteria. A meta-analysis from 2010 examining late-life depression was judged by the authors to have adequately addressed our research question for this condition, and it was removed from our condition list as no subsequent studies were found.Citation9 In total, 46 studies pertaining to COPD, dementia, PD, HF, stroke/TIA, AMI, and diabetes involving 112,669 subjects constituted the final analysis (). A summary of data abstracted from each included study is provided in the “Supplementary materials” section.

An attempt at meta-analysis of all included studies was considered but subsequently deemed impractical due to the marked heterogeneity in the raw data as a result of widely differing study populations, settings, study designs, choice of reference diagnostic criteria, and analytic methods.

Therefore, meta-analysis was restricted to data pooled from subgroups of five or more similarly designed studies for each condition, which employed the same measures of diagnostic accuracy and comparable clinical diagnostic criteria and reference standards. Although not specified in the original protocol, due to the poor quality of the studies, the decision was made to restrict meta-analysis to those studies where the forest plot of diagnostic accuracy, the funnel plot of the diagnostic accuracy versus the study size, and a plot of diagnostic accuracy versus the confidence interval (CI) range suggested the absence of significant heterogeneity or bias.

Disease-specific results

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

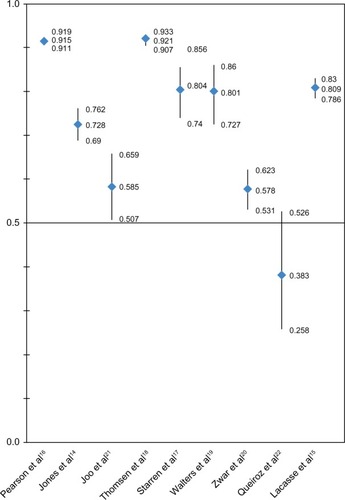

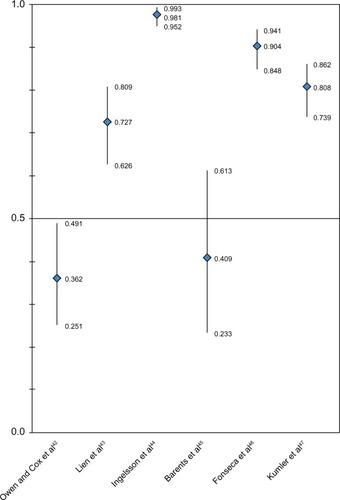

Of the 12 articles relating to COPD, ten assessing overdiagnosis using current reference criteria revealed 1–Sp results between 11.7% and 28.7% and 1–PPV results between 8.5% and 52.6%.Citation13–Citation22 Eight studies assessing overdiagnosis met our criteria for attempting meta-analysis. However, on reviewing the forest plot of PPVs with 95% CI and the funnel plots of PPVs against CI range and participant numbers to exclude bias, no consistent relation was found and no further meta-analysis was attempted (). Restricting the analysis to the four highest quality studies, 1–PPV varied from 19.6% to 42.2%.Citation14,Citation17,Citation19,Citation20

Figure 3 PPV with 95% CIs for COPD subgroup.

Failure to perform spirometry, improper spirometry technique, incorrect interpretation of the results, and atypical presentations appeared to contribute to overdiagnosis.Citation15,Citation19 Prebronchodilator spirometry use led to COPD misdiagnosis in patients who had asthma in two separate studies (1–PPV of 11% and 20%).Citation13,Citation14 There was also a positive relationship between the number of comorbidities and rates of COPD overdiagnosis.Citation13,Citation20

Three studies assessed the underdiagnosis of COPD with 1–Sn ranging from 35.6% to 71.4% and 1–NPV ranging from 27.8% to 51.8%.Citation16,Citation21,Citation22 These studies assessed populations with risk factors for COPD and likely overestimated the degree of underdiagnosis in the general population. The highest quality study determined that in patients 65 years or older with symptoms of, risk factors for, and treatment consistent with COPD, the disease was undiagnosed in ∼35% of cases.Citation21

In defining COPD, the current Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines use a fixed postbronchodilator cutoff value of the ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) of <0.70. An alternative definition has been suggested using values below the 95th percentile (or <5% lower limit of normal) of the distribution of FEV1/FVC values within older populations. When compared with the lower limit of normal, the fixed cutoff criteria resulted in 1–PPVs of 27%–29% in a large high-quality study.Citation10 In another study of 71 asymptomatic nonsmoking participants aged >70 years, the GOLD criteria labeled 35% of participants as having COPD, increasing to 50% in those >80 years, results considered clinically implausible.Citation6 These studies suggest that the current reference criteria for COPD diagnosis may be inappropriate in older patients.

The effect of increasing age on diagnostic accuracy was mixed in four high-quality studies.Citation13,Citation15,Citation19,Citation20

Dementia

Ten studies assessed diagnostic validity, including one systematic review. Two studies investigated dementia as a broad category, while six looked at Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and four at dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Eight studies used neuropathological reference criteria, with the remaining two using clinical criteria.

Studies assessing overdiagnosis showed 1–Sp ranging from 0% to 50% and 1–PPV from 16% to 40%.Citation23–Citation31 A single study assessed dementia in general and calculated a 1–Sp of 14%, using clinical diagnostic criteria.Citation29 Overdiagnosis of AD was assessed in six studies,Citation23–Citation25,Citation27,Citation28,Citation30 the most rigorous being a neuropathological study, which revealed a 1–Sp of between 29.2% and 40.5% and a 1–PPV between 16.7% and 37.8%.Citation23 All four studies assessing overdiagnosis in DLB had significant bias and applicability concerns.Citation26–Citation28,Citation31 Notwithstanding, overdiagnosis of DLB appeared less prevalent compared to other types of dementia, with three studies showing a 1–Sp of <5%.Citation26–Citation28

Overdiagnosis was more common in patients with milder disease and more comorbidities, with the exception of DLB.Citation28,Citation30

Underdiagnosis of dementia appears more prevalent.Citation23–Citation28,Citation31,Citation32 A systematic review of eight studies of the under-diagnosis of dementia in the primary care setting estimated a 1–Sn of 51% (0%–91%).Citation32 Underdiagnosis of AD was assessed in five further studies. 1–Sn was highly variable from 4% to 75%, with 1–NPV from 6.5% to 30%.Citation23–Citation25,Citation27,Citation28 Four studies examining underdiagnosis in DLB calculated 1–Sn from 71% to 100% and 1–NPV from 10% to 11%.Citation26–Citation28,Citation31 Patients with poor access to health care, lower socioeconomic status, and lower levels of education were more likely to be underdiagnosed.Citation32 Underdiagnosis was also prevalent at the extremes of age, attributed in the older population to the increasing prevalence of HTN, diabetes, and vascular disease.Citation24,Citation32

Parkinson’s disease

Nine studies explored the validity of a diagnosis of PD, all assessing overdiagnosis, with five also investigating under-diagnosis. In relation to overdiagnosis, four studies compared clinical diagnoses with clinicopathological reference criteria, reporting 1–Sp of between 1% and 12%.Citation33–Citation36 The remaining five studies used specialist clinical assessments as reference criteria, against which clinical diagnoses made by nonspecialists demonstrated 1–Sp between 15% and 27%.Citation37–Citation41 Specialist diagnosis was consistently associated with less overdiagnosis in three studies, which demonstrated a 1–PPV of 1.4%–25% for specialists and 27%–47% for nonspecialists.Citation35,Citation37,Citation39 Similar results were found in a more recent study comparing the clinical diagnosis of a specialist with results of FP-CIT SPECT (N-u-fluoro-propyl-2b carbomethoxy-3b-(4-iodophenyl) nortropane single photon emission computed tomography) scanning in 38 patients which reported a 1–Sp of 15%–21% and 1–PPV of 17%–26%.Citation38

Overdiagnosis was more prevalent in patients with no bradykinesia, rigidity, resting tremor, hypomimia, or monotonous speech, as well as less frequent falls, less severe disease, and higher scores on cognitive testing.Citation37 Patients receiving low doses of anti-Parkinson medications, whose dose had not increased in 3 years, who had been on monotherapy for ≥5 years, and who had neither a documented response to medications nor clinical progression were more commonly overdiagnosed.Citation37,Citation39 Patients diagnosed and followed up by a specialist were less susceptible to overdiagnosis.Citation35,Citation37 Early dementia and secondary parkinsonism were the most common etiologies misdiagnosed as PD.Citation34

Five studies assessed underdiagnosis, with two clinico-pathological studies reporting 1–Sn between 9% and 50% and 1–NPV between 1% and 10%.Citation35,Citation36 Another study using a validated clinical reference criteria demonstrated a similar 1–Sn of 7% versus 27% for specialists and nonspecialists, respectively.Citation37 The FP-CIT SPECT scanning study reported 1–Sn between 20% and 47%, reflecting the high sensitivity of this imaging technique in early PD.Citation38

Factors associated with underdiagnosis included lower disease severity, shorter disease duration, living in a nursing home, and the absence of typical complications of PD and/or its treatment, such as depression and dyskinesia.Citation37

Increasing age was shown to be associated with higher rates of both over- and underdiagnosis.Citation40

Heart failure

Seven studies explored the validity of a diagnosis of HF. Six studies assessing overdiagnosis of HF reported 1–Sp between 0.7% and 16.5% and 1–PPV between 2% and 64%.Citation8,Citation42–Citation47 While these studies met our criteria for attempted meta-analysis, this was deemed not feasible after reviewing the forest plot of PPVs with 95% CI and the funnel plots of PPVs against CI range and participant numbers to exclude bias ().

Figure 4 PPV with 95% CIs for heart failure subgroup.

Those who were diagnosed in a hospital setting showed less overdiagnosis, with 1–PPVs of 1.9%–27.3% compared to 59.1%–63.8% for those diagnosed elsewhere.Citation42–Citation47 Nursing home residents had a 1–PPV of 59% compared to 19% in a similarly designed study of community-dwelling patients.Citation45,Citation47 Comorbidities, particularly atrial fibrillation, COPD, and obesity, were more prevalent among falsely diagnosed cases.Citation42,Citation45

Underdiagnosis was assessed in four studies in which 1–Sn was 17.1% in one autopsy-based studyCitation8 and much higher (62.5% and 70.6%) in two high-quality studiesCitation45,Citation47 with guideline-endorsed clinical and echocardiographic reference criteria.

Increasing age was associated with poorer diagnostic accuracy, attributed to atypical presentations, higher number of comorbidities, and older patients being less likely to receive echocardiograms.Citation8,Citation43

Stroke and TIA

Three studies assessed misdiagnosis of strokes and TIAs; two were high quality and assessed overdiagnosis.Citation48–Citation50 These studies compared the clinical diagnoses of stroke or TIA recorded in patient registries and emergency department notes with diagnoses made by experts upon review of all available clinical data. 1–PPV of 20%–24% was reported for stroke and 32%–62% for TIA.

Gradual onset, nonspecific symptoms, and past history of unexplained transient neurological syndromes were significantly more common in cases falsely diagnosed as TIA.Citation49 The difficulty in diagnosing these conditions was highlighted by a disagreement rate between experts of 6% and 11% for stroke and TIA, respectively.Citation48

Underdiagnosis was assessed in a single study with significant bias and applicability concerns. The combined 1–Sn for stroke and TIA was 9%, with underdiagnosis occurring more commonly in cases that presented without language or motor deficits.Citation50

The effect of increasing age on the extent of misdiagnosis was mixed.Citation48,Citation49

Acute myocardial infarction

Four studies were included which assessed misdiagnosis of AMI. Two assessed underdiagnosis, with one showing missed diagnosis of AMI in 34% of cases (1–Sn) confirmed at autopsy,Citation8 while a study based on a clinical reference standard reported a much lower rate (2%).Citation51 Underdiagnosis was less prevalent in higher volume emergency departments.Citation51

While no study was found assessing overdiagnosis against current reference standards, two explored the validity of these reference standards.Citation52,Citation53 The validity of the new universal definition for AMI (change in cardiac troponin combined with either clinical symptoms, ischemic electrocardiogram changes, or imaging findings of ischemic or necrotic myocardium) reported a 1–PPV of 0.6% in a healthy group aged 70 years and 7% in a group (median age 67 years) who had suffered a non-ST-elevation AMI 3 months previously.Citation53 A recent high-quality study assessing highly sensitive tro-ponin T testing (HSnTnT) demonstrated a significant relationship between older age and higher HSnTnT.Citation52 This resulted in significant overdiagnosis in those ≥70 years with HSnTnT >14.0 ng/L, a 1–Sp of 49%, and 1–PPV of 58%, compared to 12% and 50%, respectively, for those <70 years old. A higher cutoff in older populations of >53.5 ng/L displayed 1–Sp of 13% and 1–PPV of 29% with a minor increase only in underdiagnosis (1–Sn recorded at only 3% and 5% for the >14.0 ng/L and >53.5 ng/L groups, respectively), suggesting that current reference ranges for HSnTnT may be inaccurate in older patients.Citation52

While these studies suggest increased rates of overdiagnosis in older patients, the effect of age on underdiagnosis was studied in a single autopsy study suggesting less under-diagnosis in older persons.Citation8

Diabetes

A single retrospective study involving 18,000 patients with diabetes from two cohorts revealed 1–PPVs of 2% and 4%.Citation54

Discussion

Overview of results

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of the rates of misdiagnosis of common diseases in older populations. While the literature was limited, our results indicate that clinically significant rates of overdiagnosis and under-diagnosis exist for six of the analyzed conditions in older patients. Unfortunately, study heterogeneity precluded meaningful meta-analysis of pooled data in deriving more precise numerical estimates of these rates.

Increasing age is often associated with lower diagnostic accuracy, with increased overdiagnosis of PD, HF, and AMI and underdiagnosis of dementia, PD, and HF. The impact of increasing age on COPD and stroke/TIA was unclear. In the case of COPD data, we hypothesize that this may have resulted from increased disease prevalence in study populations and the use of prevalence-dependent diagnostic measures.

Strengths and limitations

Our review has several strengths in terms of fully scoped and iterative literature searches, attempts to ascertain data specific to older populations (including contact with study authors), assessment of both over- and underdiagnosis rates, study selection criteria that stipulated use of diagnostic reference standards, attempts where appropriate to perform meta-analysis, and efforts to identify factors that predisposed to misdiagnosis.

Limitations included marked heterogeneity in population characteristics, clinical setting, disease severity, prevalence of comorbidities, age distribution, sample size, and analytic methods. Methodological quality of included studies, as assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool, was highly variable, with investigators unblinded to both clinical diagnosis and reference criteria in 40% of studies. In some instances, the reference criteria used had not been validated in older populations, as exemplified by GOLD spirometric cutoff values used to diagnose COPD and HSnTnT reference ranges in AMI. Studies also varied in how they calculated misdiagnosis rates (sensitivity/specificity or predictive values), generating concerns about the impact of disease prevalence on the stated estimates of misdiagnosis.

Research rarely focused on older patients with multiple comorbidities, poor functional reserve and polypharmacy, subgroups at the highest risk of complications from misdiagnosis. Clinician and patient factors predisposing to diagnostic error were infrequently studied.Citation10,Citation55

Implications for practice

Our results emphasize the need for clinicians to be systematic and circumspect in verifying past diagnoses or making a new diagnosis in older patients. In particular, clinicians need to familiarize themselves with clinical features and investigations that best discriminate between the presence and absence of disease in older populations The presence of physical comorbidities was consistently associated with lower accuracy with regard to the diagnoses of COPD, dementia, PD, HF, stroke/TIA, and AMI, possibly because somatic complaints and fatigue arising from concurrent diseases mask features that support or refute the index diagnosis.

Conclusion

Diagnostic errors involving older patients are common and comprise both overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis. Factors that predispose to misdiagnosis in older patients must be given emphasis in training continuing education programs and clinical practice guidelines.

Author contributions

All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Justin Scott, biostatistician from the Queensland Facility for Advanced Bioinformatics, and Christine Dalais, University of Queensland Library. The authors also wish to thank Dr Jonathon Belsey, Dr Simon Lusignan, Dr Alfredo J Mansur, Dr Rafael Saad, Assistant Professor Shyam Prabhakaran, Dr Min Joo, and Dr Julia Walters for assisting in this review by providing additional data from their studies.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ScottIJayathissaSQuality of drug prescribing in older patients: is there a problem and can we improve it?Intern Med J201040171819712203

- ElyJWKaldjianLCD’AlessandroDMDiagnostic errors in primary care: lessons learnedJ Am Board Fam Med2012251879722218629

- NealeGHoganHSevdalisNMisdiagnosis: analysis based on case record review with proposals aimed to improve diagnostic processesClin Med2011114317321

- Newman-TokerDEPronovostPJDiagnostic errors – the next frontier for patient safetyJAMA2009301101060106219278949

- AlemayehuBWarnerKEThe lifetime distribution of health care costsHealth Serv Res200439362764215149482

- HardieJABuistASVollmerWMEllingsenIBakkePSMorkveORisk of over-diagnosis of COPD in asymptomatic elderly never-smokersEur Respir J20022051117112212449163

- MoynihanRDoustJHenryDPreventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthyBMJ2012344e350222645185

- SaadRYamadaATPereira da RosaFHGutierrezPSMansurAJComparison between clinical and autopsy diagnoses in a cardiology hospitalHeart200793111414141917395672

- MitchellAJRaoSVazeADo primary care physicians have particular difficulty identifying late-life depression? A meta-analysis stratified by agePsychother Psychosom201079528529420616623

- BrazzaleDJUpwardALPrettoJJEffects of changing reference values and definition of the normal range on interpretation of spirometryRespirology20101571098110320874746

- MarengoniAAnglemanSMelisRAging with multi-morbidity: a systematic review of the literatureAgeing Res Rev201110443043921402176

- NaughtonCBennettKFeelyJPrevalence of chronic disease in the elderly based on a national pharmacy claims databaseAge Ageing200635663363617047009

- BelliaVBattagliaSCatalanoFAging and disability affect misdiagnosis of COPD in elderly asthmatics: the SARA studyChest200312341066107212684295

- JonesRCDickson-SpillmannMMatherMJMarksDShackellBSAccuracy of diagnostic registers and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the Devon primary care auditRespir Res200896218710575

- LacasseYDaigleJMMartinSMaltaisFValidity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease diagnoses in a large administrative databaseCan Respir J2012192e5e922536584

- PearsonMAyresJGSarnoMMasseyDPriceDDiagnosis of airway obstruction in primary care in the UK: the CADRE (COPD and Asthma Diagnostic/management REassessment) programme 1997–2001Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20061443544318044099

- StarrenESRobertsNJTahirMA centralised respiratory diagnostic service for primary care: a 4-year auditPrim Care Respir J201221218018622430040

- ThomsenRWLangePHellquistBValidity and underrecording of diagnosis of COPD in the Danish National Patient RegistryRespir Med201110571063106821320769

- WaltersJAWaltersEHNelsonMFactors associated with misdiagnosis of COPD in primary carePrim Care Respir J201120439640221687918

- ZwarNAMarksGBHermizOPredictors of accuracy of diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in general practiceMed J Aust2011195416817121843115

- JooMJAuDHFitzgibbonMLMcKellJLeeTADeterminants of spirometry use and accuracy of COPD diagnosis in primary careJ Gen Intern Med201126111272127721713542

- QueirozMCMoreiraMARabahiMFUnderdiagnosis of COPD at primary health care clinics in the city of Aparecida de Goiania, BrazilJ Bras Pneumol201238669269923288113

- BeachTGMonsellSEPhillipsLEKukullWAccuracy of the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease at National Institute on Aging Alzheimer Disease Centers, 2005–2010J Neuropathol Exp Neurol201271426627322437338

- GayBETaylorKIHohlUTolnayMStaehelinHBThe validity of clinical diagnoses of dementia in a group of consecutively autopsied memory clinic patientsJ Nutr Health Aging200812213213718264641

- JobstKABarnetsonLPShepstoneBJAccurate prediction of histologically confirmed Alzheimer’s disease and the differential diagnosis of dementia: the use of NINCDS-ADRDA and DSM-III-R criteria, SPECT, X-ray CT, and APO E4 medial temporal lobe dementias. The Oxford Project to Investigate Memory and AgingInt Psychogeriatr19979suppl 1191222 discussion 247–1529447442

- LitvanIMacIntyreAGoetzCGAccuracy of the clinical diagnoses of Lewy body disease, Parkinson disease, and dementia with Lewy bodies: a clinicopathologic studyArch Neurol19985579699789678315

- LopezOLLitvanICattKEAccuracy of four clinical diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of neurodegenerative dementiasNeurology19995361292129910522887

- NelsonPTJichaGAKryscioRJLow sensitivity in clinical diagnoses of dementia with Lewy bodiesJ Neurol2010257335936619795154

- PhungTKAndersenBBHoghPKessingLVMortensenPBWaldemarGValidity of dementia diagnoses in the Danish hospital registersDement Geriatr Cogn Disord200724322022817690555

- RasmussonDXBrandtJSteeleCHedreenJCTroncosoJCFolsteinMFAccuracy of clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease and clinical features of patients with non-Alzheimer disease neuropathologyAlzheimer Dis Assoc Disord19961041801888939276

- VergheseJCrystalHADicksonDWLiptonRBValidity of clinical criteria for the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodiesNeurology19995391974198210599768

- BradfordAKunikMESchulzPWilliamsSPSinghHMissed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: prevalence and contributing factorsAlzheimer Dis Assoc Disord200923430631419568149

- JellingerKAHow valid is the clinical diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease in the community?J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry20037471005100612810810

- HughesAJDanielSELeesAJImproved accuracy of clinical diagnosis of Lewy body Parkinson’s diseaseNeurology20015781497149911673599

- HughesAJDanielSEBen-ShlomoYLeesAJThe accuracy of diagnosis of parkinsonian syndromes in a specialist movement disorder serviceBrain2002125pt 486187011912118

- FoltynieTMatthewsFEIshiharaLBrayneCMRCCFASThe frequency and validity of self-reported diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease in the UK elderly: MRC CFAS cohortBMC Neurol200662916925826

- SchragABen-ShlomoYQuinnNHow valid is the clinical diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease in the community?J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200273552953412397145

- BajajNPGontuVBirchallJPattersonJGrossetDGLeesAJAccuracy of clinical diagnosis in tremulous parkinsonian patients: a blinded video studyJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry201081111223122820547625

- NewmanEJBreenKPattersonJHadleyDMGrossetKAGrossetDGAccuracy of Parkinson’s disease diagnosis in 610 general practice patients in the West of ScotlandMov Disord200924162379238519890985

- FeldmanALJohanssonALGatzMAccuracy and sensitivity of parkinsonian disorder diagnoses in two Swedish national health registersNeuroepidemiology201238318619322472568

- MearaJBhowmickBKHobsonPAccuracy of diagnosis in patients with presumed Parkinson’s diseaseAge Ageing19992829910210350403

- OwenACoxSDiagnosis of heart failure in elderly patients in primary careEur J Heart Fail200131798111163739

- LienCTGillespieNDStruthersADMcMurdoMEHeart failure in frail elderly patients: diagnostic difficulties, co-morbidities, polypharmacy and treatment dilemmasEur J Heart Fail200241919811812669

- IngelssonEArnlovJSundstromJLindLThe validity of a diagnosis of heart failure in a hospital discharge registerEur J Heart Fail20057578779115916919

- BarentsMvan der HorstICVoorsAAHillegeJLMuskietFAde JongsteMJPrevalence and misdiagnosis of chronic heart failure in nursing home residents: the role of B-type natriuretic peptidesNeth Heart J200816412312818427636

- FonsecaCSarmentoPMMarquesFCeiaFValidity of a discharge diagnosis of heart failure: implications of misdiagnosingCongest Heart Fail200814418719118772623

- KumlerTGislasonGHKirkVAccuracy of a heart failure diagnosis in administrative registersEur J Heart Fail200810765866018539522

- KrarupLHBoysenGJanjuaHPrescottETruelsenTValidity of stroke diagnoses in a National Register of PatientsNeuroepidemiology200728315015417478969

- PrabhakaranSSilverAJWarriorLMcClenathanBLeeVHMisdiagnosis of transient ischemic attacks in the emergency roomCerebrovasc Dis200826663063518984948

- MorgensternLBLisabethLDMecozziACA population-based study of acute stroke and TIA diagnosisNeurology200462689590015037689

- SchullMJVermeulenMJStukelTAThe risk of missed diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction associated with emergency department volumeAnn Emerg Med200648664765517112926

- Chenevier-GobeauxCMeuneCFreundYInfluence of age and renal function on high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T diagnostic accuracy for the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarctionAm J Cardiol2013111121701170723540652

- EggersKMLindLVengePLindahlBWill the universal definition of myocardial infarction criteria result in an overdiagnosis of myocardial infarction?Am J Cardiol2009103558859119231317

- de LusignanSKhuntiKBelseyJA method of identifying and correcting miscoding, misclassification and misdiagnosis in diabetes: a pilot and validation study of routinely collected dataDiabet Med201027220320920546265

- SchermerTRSmeeleIJThoonenBPCurrent clinical guideline definitions of airflow obstruction and COPD overdiagnosis in primary careEur Respir J200832494595218550607