?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

We aimed to evaluate whether the enhancement of the liver accumulation and anti-inflammatory activity of dexamethasone acetate (DXMA) could be achieved by incorporating it into nanostructured lipid carrier (NLCs). DXMA-NLCs were prepared using a film dispersion-ultrasonication method and characterized in terms of particle size, PDI, zeta potential, differential scanning calorimetry, drug loading capacity, encapsulation efficiency, and in vitro release. The biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of DXMA-NLCs in mice were significantly different from those of the DXMA solution (DXMA-sol). The peak concentration of DXMA-NLCs was obtained half an hour after intravenous administration. More than 55.62% of the total administrated dose was present in the liver. An increase of 2.57 fold in the area under the curve was achieved when compared with that of DXMA-sol. DXMA-NLCs exhibited a significant anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective effect on carrageenan-induced rats and carbon tetrachloride-induced mice compared with DXMA-sol. However, the effect was not in proportion to the dosage. The intermediate and low dosages presented better effects than DXMA-sol. All results indicate that NLCs, as a novel carrier for DXMA, has potential for the treatment of liver diseases, increasing the cure efficiency and decreasing the side effects on other tissues.

Inflammatory processes are involved in a large number of liver diseases and may lead to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis.Citation1 Dexamethasone acetate (DXMA) is a synthesized glucocorticoid, which has been used as an anti-inflammatory drug in the treatment of chronic active hepatitis for the prevention of liver fibrosis.Citation2 Although DXMA enhances hepatocyte viability and improves the expression of liver-specific genes in liver diseases, the response rates obtained from a series of recent clinical trials were poor, which can be explained by the following factors. Firstly, DXMA has poor water solubility and is almost insoluble in most physiologically compatible and pharmaceutically acceptable solvents, both of which limit its clinic applications.Citation3 Secondly, DXMA does not act specifically on liver cells, and long term use of large doses may lead to many side effects, such as osteoporosis, an increased risk of infections, and Cushing’s syndrome, especially during chronic use.Citation1 To overcome these problems, micro/nanoparticulate delivery systems were utilized for the encapsulation of DXMA. Polytrimethylene carbonate and PLGA were used to improve the aqueous solubility and in vitro release of dexamethasone, but in vivo results were not reported.Citation4–Citation6

Particulate carriers usually accumulate in the liver by passive targeting upon parenteral administration.Citation7 Oxymatrine and 5-fluorouracil prodrug were incorporated in solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) and showed higher liver targeting efficacy compared with free drug.Citation8,Citation9 Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs) are the second generation of lipid nanoparticles, composed of a binary mixture of solid lipid and a spatially different liquid lipid as a carrier.Citation6 Though the major advantages of NLCs include increased drug loading capacity and decreased drug expulsion compared with SLNs, to date, very few researchers have systematically explored the in vivo liver targeting of NLCs.

Recently, we developed liver targeting DXMA-NLCs by a film dispersion-ultrasonication method. In this study we aimed to evaluate whether the enhancement of the liver accumulation and anti-inflammatory activity of DXMA could be obtained by incorporated into NLCs. The biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of DXMA-NLCs were studied in normal mice and the therapeutic efficacy was investigated on carrageenan-induced rats and carbon tetrachloride-induced mice for the first time.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and animals

DXMA was supplied by Tianyao Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. (Tianjin, P.R.C.). Pluronic 188 (F68) and carrageenan were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Purified egg yolk lecithin (Lipoid E80) was obtained from LIPOID GMBH (Ludwigshafen, Germany). Soybean oil for parenteral use was supplied by Beiya Co. Ltd. (Tieling, P.R.C.) and tween 80 from Bodi Chemicals Co. Ltd. (Tianjin, P.R.C.). Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) was obtained from Kelong Chemicals Co. Ltd. (Chengdu, P.R.C.). Alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and alkaline phosphatase assay kits were purchased from Jiancheng Institute of Biotechnology (Nanjing, P.R.C.). A hydroxyproline assay kit was supplied by Bei Fang Wei Ye Co. Ltd. (Beijing, P.R.C.). All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Kunming mice weighing between 18 and 22 g and Wistar rats weighing between 180 and 200 g were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center of Sichuan University (Chengdu, P.R.C.).

Preparation of DXMA loaded NLCs

DXMA-NLCs were prepared by a film dispersion-ultrasonication method.Citation10 Briefly, 15 mg of DXMA, 100 mg of Soybean oil (SO), and 100 mg of lecithin were dissolved in CH2Cl2. The solution was evaporated under reduced pressure to remove the solvent and form a thin layer of uniform film on the wall of a round-bottom flask. A total of 20 mL of aqueous phase containing surfactants F68(2%, w/v) and tween 80(2%, w/v) was added to disperse the film. The mixture was then further dispersed ultrasonically for 5 minutes to obtain NLCs. DXMA-containing NLCs were then purified by filtration through a cellulose acetate membrane (0.8 μm) to eliminate drug crystals. After purification, the NLC dispersions were freeze-dried for storage with mannitose as the cryoprotector.

Characterization of NLCs

The NLCs were characterized for their size, PDI, and zeta potential with a Malvern Zatasize NanoZS90 (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Malvern, UK). Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and 31P Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (31P NMR) of blank NLCs, DXMA, DXMA-NLCs, and a physical mixture of blank NLCs and DXMA (the same ratio as that of the DXMA-NLCs) were performed on a DSC 204 (NETZSCH, Selb, Germany) and an AV300 spectrometer (Bruker, Rheinstetten, Germany).

The drug loading capacity (LC%) and encapsulation efficiency (EE%) were determined in triplicate by HPLC. The freeze-dried samples were redispersed in a solution of methanol/water (7:3, v/v) and sonicated. Subsequently, the suspensions were centrifuged (11,100 × g, 5 minutes), and the supernatant was assayed by HPLC for the total amount of DXMA in lipid nanoparticles. The amount of DXMA contained in the NLCs was determined by resuspending the same freeze-dried samples in 1 mL water, adding 0.2 mL NaCl solution (0.9%) to salt out the unincorporated drugs and centrifuging (18,000 × g, 20 minutes). The upper suspensions were then added to methanol, sonicated, and centrifuged (11,100 × g, 5 minutes). Finally, the supernatant was tested by the same HPLC method for the determination of DXMA entrapped within the NLCs. The HPLC system consisted of an Alltech Model 426 HPLC Pump, an Alltech UVIS-201 Absorbance Detector, and an Allchrom plus Client/Server data operator (Alltech International, Inc., Virginia, USA). The mobile phase contained a ratio of methanol: water of 70:30. A Shimpack CLC-ODS C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, Dikma Diamonsil®, Dikma Inc., Shanghai, P.R.C) was eluted at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The eluate was monitored at 30°C and DXMA was assayed at a wavelength of 240 nm. EE% and LC% of DXMA loaded NLCs were calculated as given below:

In vitro release study of DXMA-NLCs

The Visking bag method was used to investigate the in vitro release of DXMA loaded NLCs. Briefly, DXMA-NLCs were resuspended in 5 mL water at a concentration of 100 μg/mL, transferred into the dialysis bag and dialyzed against 45 mL phosphate buffer (pH 7.4, containing 0.03 wt% SDS). During dialysis, a constant temperature shaker (Shenzhen Worldwide Industry, Co. Ltd., Shenzhen, P.R.C) was used, thermostatted at 37 ± 1°C and mechanically shaken at a suitable rotation speed.

At designated time intervals, 1 mL samples of the dialysis medium was taken for HPLC measurement of DXMA and the same volume of fresh medium was added. The release experiments were performed in triplicate.

In vivo biodistribution and pharmacokinetic studies of DXMA-NLCs

The Sichuan University animal ethical experimentation committee approved all procedures of the in vivo studies, according to the requirements of the National Act on the use of experimental animals (P.R.C.). Kunming mice received a single intravenous (iv) injection of DXMA-NLCs or DXMA solution at a DXMA equivalent dose of 10 mg/kg. The mice were sacrificed at 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 hours after iv administration. Blood samples were collected from the orbit venous plexus and plasma samples were obtained by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 minutes. The tissues, including heart, lung, liver, spleen, and kidney were harvested and accurately weighed and homogenized. Plasma and tissue samples within the same group were pooled together for further analysis (n = 5).

The DXMA concentrations in the plasma or tissues were determined by an HPLC assay. The extraction procedure was as follows. Plasma or tissue homogenates (0.5 mL) were mixed with 0.1 mL methyltestosterone solution (8.66 μg/mL) as the internal standard and 0.2 mL phosphate buffer (pH = 2.0). The mixture was vortexed with 3 mL acetoacetate and then centrifuged (5,900 × g, 10 minutes). A total of 2 mL of supernatant was evaporated to dryness. Finally, the residue was redissolved in 0.2 mL methanol, following centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes. Following this, 20 μL of the clear supernatant was injected into the HPLC system as described above.

Plasma and tissue concentration data obtained were pooled to provide mean concentration data. Pharmacokinetic parameters in plasma and organs were calculated using a statistical moment algorithm and were obtained by calculating the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) using the linear trapezoidal rule and extrapolating this value to infinity by dividing the last measurable concentration by the elimination rate constant.

The anti-inflammatory effect of DXMA-NLCs on carrageenan-induced rats

An anti-inflammatory test of DXMA-NLCs was performed according to the method developed by Lange et al.Citation11 Wistar rats were randomly divided into 5 groups (n = 8). Group 1 (control) received saline; groups 2 and 3 were injected with DXMA-NLCs (DXMA equivalent dose of 3 mg/kg or 0.6 mg/kg); and groups 4 and 5 received DXMA-sol (3 mg/kg or 0.6 mg/kg). Drugs and saline were given through the tail veins 1 hour before subcutaneous injection of carrageenan into the right hind paws. The paw volume was measured before drug administration and then at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 hours after carrageenan injection, using a digital plethysmometer. The amount of paw swelling was determined from time to time and expressed as follows:

Hepatoprotective effects of DXMA-NLCs on carbon tetrachloride-induced mice

Animal treatments

Kunming mice were divided into 8 groups. Group 1 received normal saline and served as the control. Animals in groups 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 were subcutaneously injected with carbon tetrachloride (40% CCl4 in olive oil, 0.2 mL/10 g) on the first day and then 0.1 mL/10 g once every 5 days for a period of 4 weeks. Group 2 received normal saline and served as a CCl4 intoxication control (CCl4 group). Group 3 received blank NLC and served as the vehicle control. Groups 4 and 5 received DXMA-sol at doses of 2 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg, respectively. Groups 6, 7, and 8 received DXMA-NLCs at a DXMA equivalent dose of 2 mg/kg, 1 mg/kg, and 0.5 mg/kg, respectively. The normal saline and drugs were administered through the tail veins once per week over a period of 4 weeks from the second day after injection of carbon tetrachloride.

Blood samples were collected from the orbit venous plexus 24 hours after the last treatment of drugs and were used for biochemical evaluations. The mice were then dissected and the livers were removed for the calculation of liver coefficients and then homogenized for the determination of hydroxyproline content.

Biochemical evaluations

Liver damage was assessed by estimating serum activities of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) using commercially available test kits. The results were expressed as activity (IU/100 mL).

Liver coefficients

After weighing the body and liver, the ratio of wet liver weight (mg) to total body weight (g) (liver coefficient) was calculated.

Hydroxyproline content

Hydroxyproline (Hyp) content in liver was determined by the Hyp assay kit spectrophotometric method according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data was expressed as Hyp (μg)/wet liver weight (g).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) and statistically assessed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences between the CCl4 group and the drug or NLC-treated groups were evaluated by the Student’s t test, with a significance level of P < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Preparation and characterization of DXMA-NLCs

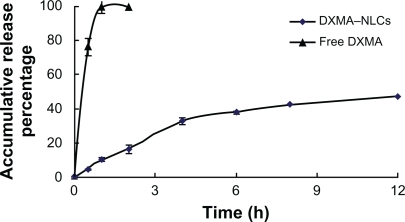

DXMA-NLCs were successfully prepared by the film dispersion-ultrasonication method using soybean oil and egg yolk lecithin as lipid materials with a mean particle size of 151 ± 3.5 nm, a PDI of 0.215 ± 0.083, a zeta potential of −38.7 ± 3.7 mv, an encapsulation efficiency of 97.11 ± 0.51%, and a drug loading capacity of 4.41 ± 0.04%. The in vitro release study revealed sustained release of drugs from DXMA-NLCs in contrast with the free DXMA (). While about 100% of the free drug was found in release medium after approximately 2 hours, less than 10% of the drug released at 1 hour and about 50% of the drug released within 12 hours from DXMA-NLCs.

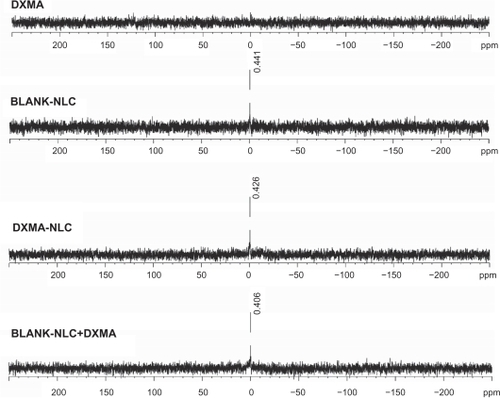

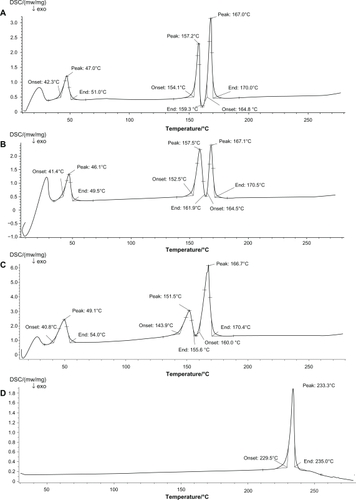

DSC analysis was performed to evaluate possible interactions between DXMA and the lipid materials (). Blank NLCs exhibited 3 melting points at 47°C, 157.2°C, and 167°C (). Similarly, drug loaded NLCs presented melting points at 46.1°C, 157.5°C, and 167.1°C (). In addition, the typical transitions of physical mixture were 49.1°C, 151.5°C, and 166.7°C (). DXMA alone showed a peak at 233.3°C as seen in . No considerable difference could be observed among blank NLCs, drug-loaded NLCs, and physical mixture, which means the loading of a small amount of drug on NLCs did not change the melting points significantly. The DSC thermograms of physical mixture and the drug-loaded NLCs did not show a melting peak for DXMA. This absence may be induced by the low amount of the drug (4.41 ± 0.04%) in DXMA-NLCs, which was coincident with the research of Mu et al.Citation12 Their team reported difficulties in detecting the endothermic peak of drug in microspheres when the drug ratio is lower than 10%.

Figure 2 Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) of Blank NLCs (A), DXMA-NLCs (B), physical mixture of blank NLCs and DXMA (C), and DXMA (D).

To further pursue the interaction between the drug and lipids, 31P NMR spectral phospholipid profiles of blank NLCs, DXMA, DXMA-NLCs, and physical mixtures of blank NLCs and DXMA were investigated (). The spectrum obtained from DXMA indicated there was no phosphonium in DXMA. A resonance around 0.40 ppm was easily observed in all the spectrum of blank NLCs, DXMA-NLCs, and the physical mixture, which was obtained from the same P-enriched fraction. This resonance indicated there is no significant chemical environmental difference of P among blank NLCs, DXMA-NLCs, and the physical mixture. Hence, there was no chemical interaction between phospholipid and other materials including the drug.

Biodistribution and pharmacokinetics in mice

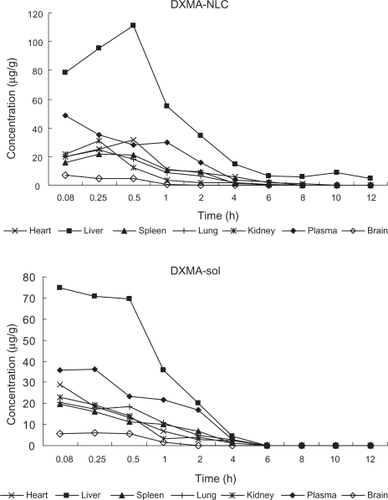

The biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of DXMA-NLCs were examined in mice. The percentage of the total administered dose (TAD) of free DXMA and NLCs in plasma and tissues at different times after iv administration are summarized in . The DXMA levels after intravenous injection of DXMA-NLCs or DXMA solution in various organs are illustrated in . Different compartment models were used to describe the pharmacokinetics of DXMA and DXMA-NLCs in plasma and tissues. The calculated data were closest to observed data when a 2-compartment model was applied. The main pharmacokinetic parameters in plasma and tissues are shown in .

Figure 4 DXMA concentrations in plasma and tissues at different time points after i.v. administration of DXMA-NLCs and DXMA-sol.

Table 1 Percentage of TAD of DXMA in plasma and tissues after iv administration of DXMA-NLCs (A) and DXMA-sol (B) in mice

Table 2 The pharmacokinetic parameters of DXMA-NLCs (A) and DXMA-sol (B) in tissues and plasma

The results shown in clearly indicate that DXMA-NLCs were preferentially accumulated in the liver. The peak concentration of DXMA-NLCs was reached at 0.5 hours after iv administration and more than 55.62% of TAD% was present in the liver, as shown in . In contrast, the peak concentration of free DXMA in the liver occurred at 0.08 hours as illustrated in and and only 2.19% of TAD% remained after 4 hours. A 2.57-fold larger area under the curve was achieved for DXMA-NLCs compared with that of DXMA (). Meanwhile, DXMA-NLCs had an increased t1/2 (1.15 hours) and decreased CL (0.07 L/h/kg) compared to free DXMA (0.38 hours, 0.17 L/h/kg), indicating that NLCs were better retained in the liver than free drug. These results clearly indicate a remarkably selective liver targeting property of DXMA-NLCs, presumably because of the general clearance of nanoparticles by the phagocytic cells.Citation13 The RES plays a major role in clearing small foreign particles from blood, which serves for the nanoparticles being passively targeted to certain phagocytic cells.Citation13 After intravenous administration with NLCs, they were mostly recognized by macrophages (MPS) owing to the physicochemical characteristics of particle size, surface charge. and surface hydrophobicity.Citation14,Citation15 An earlier report by Reddy indicated that negatively charged SLNs have a significantly higher uptake in RES organs, such as the liver and spleen.Citation16 Our results for NLCs were in agreement with that report. At the same time, because the SLN uptake by RES is mediated by particle adsorption of blood proteins and opsonins,Citation17 increasing the hydrophobicity of the particles should increase the incidence of adsorption.Citation18,Citation19 Therefore, in our study, the lipid matrix, with soybean as the core material and lecithin as the surface material, provided hydrophobic surfaces of NLCs, leading to enhanced phagocytosis of NLCs.Citation20 These results are similar to those observed with hydrophobic polystyrene particles, which were intensively taken up by cells with phagocytic activity.Citation21–Citation23 Similar liver targeting of 9-nitrocamptothecin NLCs has also been demonstrated by Li et al.Citation24

In most reported studies, non stealth SLN formulations lead to significantly higher levels of drug remaining in the systemic circulation for longer periods of time compared to the free drug and this was also the case in our study.Citation7 The AUC of DXMA delivered by NLCs in plasma was 1.21-fold higher than in corresponding free drug solutions. The half life in plasma of DXMA was also increased when administered via NLCs.

Although a study of the anti-Parkinsonian bromocriptine NLCs indirectly demonstrated that higher brain levels of bromocriptine were achieved after administration of NLCs,Citation25 a higher drug level in the brain was not observed in our study. The AUC of NLCs (2.23 μgh/g) was lower than that of the free drug (2.72 μgh/g).

The anti-inflammatory effect of DXMA-NLCs on carrageenan-induced rats

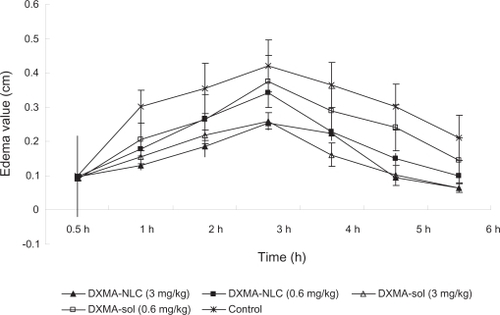

The anti-inflammatory effect of DXMA-NLCs was investigated on carrageenan-induced rats. shows the edema value of DXMA-NLCs and DXMA-sol groups, induced by carrageenan, demonstrating that both DXMA-NLCs and DXMA-sol were able to prevent edema formation compared with the control group (P < 0.05). Furthermore, the DXMA-NLCs group exhibited more significant responses at lower-dose from 3 to 6 hours after carrageenan injection than the DXMA-sol group at the same dose (P < 0.05). The percent inhibition value 5 hours after administration was found to be significantly higher for DXMA-NLCs (44.9% ± 1.70%) compared with DXMA-sol (14.8% ± 5.5%, P < 0.05). Also, in a study of the anti-inflammatory activity of DXMA incorporated into a lipid emulsion, the effect of a DXMA emulsion at a low dosage was found to be as potent as DXMA sodium phosphate at a high dosage.Citation26

Hepatoprotective effects of DXMA-NLCs on carbon tetrachloride-induced mice

Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) is a classical hepatotoxicant that causes rapid liver damage progressing from steatosis to centrilobular necrosis. Long term administration of CCl4 causes chronic liver injury, and the CCl4-induced animal model is a widely accepted as producing hepatic fibrosis.Citation27,Citation28 As shown in , the liver coefficient, contents of Hyp, serum levels of AKP, AST, ALT were all significantly increased after CCl4 treatment, which together imply the successful establishment of the model. The contents of Hyp, serum levels of enzymes in the blank NLC group were close to that of the CCl4 group, suggesting that blank NLC had no obvious impairing effect on the liver. When administered with DXMA and DXMA-NLCs, the aforementioned parameters were all significantly decreased (P < 0.05). It should be stressed that the levels of the liver coefficient and Hyp contents of DXMA-NLCs group at the intermediate dose (1 mg/kg) were 56.80 mg/g, 0.22 ± 0.39 μg/mg liver, respectively, which were much lower than those of the DXMA-sol group (65.25 mg/g, 0.66 ± 0.42 μg/mg liver, P < 0.05) with the same dose. Even if no remarkable differences were found for high dose groups between DXMA and DXMA-NLCs, the protecting effect of DXMA-NLCs at intermediate and low dosages was equal to the effect generated by drug solutions at high dosage (2 mg/kg, P > 0.05). All of these results may be related to the liver accumulation of NLCs. From the aforementioned in vivo biodistribution results, we can see a 2.57-fold larger area under the curve, an increased t1/2 (1.15 hours), and decreased CL (0.07 L/h/kg) were achieved by DXMA-NLCs compared with that of DXMA (). Furthermore, contributions from diverse accumulation in the liver may be responsible for the different hepatic protection effect between DXMA-NLCs and DXMA-sol. In this study, DXMA-NLCs with a mean particle size of 151 ± 3.5 nm, a zeta potential of −38.7 ± 3.7 mv, and surface hydrophobicity may be mainly taken up by reticuloendothelial systems and transported into nonparenchymal hepatic cells in liver. Kuffer cells, stellate cells, endothelial cells are the members of nonparenchymal hepatic cells, which play a pivotal role in continuing the inflammation with releasing cytokine. Interference with this cytokine release by DXMA could inhibit cells factor release and relive hepatic inflammation. However, for free DXMA, Melgert et al reported it is always accumulated in parenchymal cells which are not the main producers of collagens.Citation1 Although further experiments concerning the hepotoprotecting effect mechanism of DXMA-NLCs are necessary, this hypothesis could explain why DXMA-NLCs generally induced lower liver coefficient and Hyp contents than DXMA.

Table 4 Serum values of AKP, AST, and ALT in CCl4 induced rats after administration of drugs

It should be stressed the dose-effect relationship problem also occurred in our research. As shown in , among DXMA and DXMA-NLCs groups, the Hyp content (0.43 μg/mg liver) decreased after injection with a high-dose of DXMA-sol (2 mg/kg), compared to a low-dose DXMA-sol (0.66 μg/mg liver, 1 mg/kg), which was consistent with the dose-effect relationship. However, as for DXMA-NLCs, the results were different. The highest anti-inflammatory effects were achieved with the intermediate dose (1 mg/kg) and low dose of DXMA-NLCs (0.5 mg/kg). Liver fibrosis is a wound-healing process that is elicited by various toxic stimuli and is always associated with inflammation that contributes to fibrogenesis.Citation28 It is also characterized by an excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, in which type I collagen predominates.Citation29 Hyp is a specific index representing the collagen content of tissues. The inhibition of hydroxyproline levels might reduce the availability of sufficient hydroxyproline required for collagen synthesis. In this study, the lower inhibitory effect caused by the highest dose of DXMA-NLCs (2 mg/kg) might be explained by the excess concentration of drug. According to the report, the anti-inflammatory effect of glucocorticoids involved in multiple cytokines and mediators of inflammation may result in the complication of the dose-effect relationship.Citation30 Some cytokines, such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β, could significantly stimulate the ICAM-1 expression in fibroblasts. Dexamethasone (DXM) markedly inhibited these stimulations but the effective concentrations and time were variable. The effect of DXM on TNF-α appeared at the lowest dosage, while for IFN-γ, the results were highly correlated with the linear dose-effect relationship and for IL-1β, the inhibitory effect after administration with DXM varied with time. DXM can increase the stimulant effect of IL-1β at 24 hours but shows an inhibitory effect at 48 hours and there were no significant differences among the different concentration groups. Another report about dose-related effects of dexamethasone on liver damage suggests that high-dose dexamethasone does not provide any additional protective effect on liver damage compared to the low-dose group.Citation31 Moreover, high-dose dexamethasone causes obvious growth retardation. Thus, a low dose of corticosteroid provides a significant reduction in liver damage without increased side effects, while a high dose is associated not with weaker fibrosis but with increased side effects. A study of dexamethasone coupled with albumin also demonstrated that at low concentrations (0.02 μM), Dexa10-HSA was more efficient at inhibiting TNF-α production than uncoupled Dexa.Citation1 Therefore, after incorporation into NLCs, DXMA also showed a complicated dosage-effect relationship.

Table 3 Liver coefficient and hydroxyproline (Hyp) content of CCl4 induced rats after administration of drugs

Another interesting thing was that there were no differences for serum levels of AKP, AST, ALT between DXMA-sol and DXMA-NLCs groups, which implies that the inhibiting effect of DXMA-NLCs on hepatic cirrhosis formation may be not directly through protecting liver parenchyma cells.Citation32 Further research is being carried out to investigate this.

Conclusion

Results gained in the present study indicated that DXMA loaded NLCs significantly improved the in vitro release, biodistribution, pharmacokinetic, and therapeutic properties of DXMA. The NLCs remarkably prolonged drug circulation time in plasma and increased drug accumulation in the liver. In research of the anti-inflammatory effects on carrageenan-induced rats and heptoprotective effect on CCl4-induced mice, DXMA-NLCs exhibited a significant anti-inflammatory and heptoprotective effect compared with DXMA-sol. However, the effect of DXMA-NLCs was not in proportion to the dosage. The intermediate and low dosages presented better anti-inflammatory and heptoprotection effects than DXMA-sol.

Acknowledgements

The research described above was supported by Ministry of Education (NCET-06-0786), National High-tech R&D Program (863 Program, 2007AA021801), and National S&T major project (2009zx09310-002).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BarbroNMPeterOVivianKJDexamethasone coupled to albumin is selectively taken up by rat nonparenchymal liver cells and attenuates LPS-induced activation of hepatic cellsJ Hepatol20003260361110782909

- SungHKDalWCChoonWKSangGKLack of therapeutic improvement of liver fibrosis in rats by dexamethasone in spite of ascites ameliorationChem Biol Interact2005152374715766921

- China Pharmacopeial ConventionChinese Pharmacopoeia2005Section 2:184185

- ZhangZDirkWGrijpmaJFPoly(trimethylene carbonate) and monomethoxy poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(trimethylene carbonate) nanoparticles for the controlled release of dexamethasoneJ Control Release200611126327016481063

- CarolinaGGNicolasTMadeleineBAmelieBEliasFEncapsulation of dexamethasone into biodegradable polymeric nanoparticlesInt J Pharm2007331215315917157461

- Gomez-GaeteCFattalESilvaLBesnardMTsapisNDexamethasone acetate encapsulation into Trojan particlesJ Control Release20081281414918374442

- JoshiMDMüllerRHLipid nanoparticles for patrnteral delivery of activesEur J Pharm Biopharm20097116117218824097

- SunJYZhouZFLiuFChenGSPharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of oxymatrine-SLNChin Pharm J20074210911095

- YuBTZhangZRZengRJStudy on the liver targeted 5-fluorouracil solid lipid nanoparticlesYao Xue Xue Bao200035704705

- LuBXiongaSBYangaHYinaXDChaoRBSolid lipid nanoparticles of mitoxantrone for local injection against breast cancer and its lymph node metastasesEur J Pharm Sci200628869516472996

- LangeMMalyuszMImproved determination of small amounts of free hydroxyproline in biological fluidsClin Chem1994409173517388070084

- MuLFengSSFabrication, characterization and in vitro release of paclitaxel (Taxol) loaded poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) microspheres prepared by spray drying technique with lipid/cholesterol emulsifiersJ Control Release20017623925411578739

- LuWHeLCWangCHLiYHZhangSQThe use of solid lipid nanoparticles to target a lipophilic molecule to the liver after intravenous administration to miceInt J Biol Macromol20084332032418619484

- ScholerNOlbrichCTabattKMüllerRHHahnHLiesenfeldOSurfactant, but not the size of solid lipid nanoparticles (SNLC) influences viability and cytokine production of macrophagesInt J Pharm2001221576711397567

- ScholerNHahnHMüllerRHLiesenfeldOEffect of lipid matrix and size of solid lipid nanoparticles (SNLC) on the viability and cytokine production of macrophagesInt J Pharm200223116717611755269

- ReddyLHSharmaRKChuttaniKMishraAKMurthyRSREtoposide incorporated tripalmitin nanoparticles with different surface charge: formulation, characterization, radiolabeling, and biodistribution studiesAAPS J20046

- FundaròACavalliRBargoniAVighettoDZaraGPGascoMRNonstealth and stealth solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) carrying doxorubicin: pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution after i.v. administration to ratsPharmacol Res20004233734310987994

- GertSSheilaOBToosDDaniloDLSurface modification of nanoparticles to oppose uptake by the mononuclear phagocyte system. AdvDrug Deliv Rev1995173148

- MüllerRHMaaseenSSchwaCMehnertWSolid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) as potential carrier for human use: interaction with human granulocytesJ Control Release199747261269

- JunzoSSatoruSAkiraSHiroshiFHidekiSTadanoriMA nanometer lipid emulsion, lipid nano-sphere (LNS®), as a parenteral drug carrier for passive drug targetingInt J Pharm2004273758315010132

- RudtSMüllerRHIn vitro phagocytosis assay of nano- and microparticles by chemiluminescence.I. Effect of analytical parameters, particle size and particle concentrationJ Control Release199222263272

- RudtSMüllerRHIn vitro phagocytosis assay of nano- and microparticles by chemiluminescence.II. Effect of surface modification by coating of particles with poloxamer on the phagocytic uptakeJ Control Release1993a255159

- RudtSMüllerRHIn vitro phagocytosis assay of nano- and microparticles by chemiluminescence. III. Uptake of differently sized surface-modified particles, and itscorrelation to particle properties and in vivo distributionEur J Pharm Sci1993b13139

- LiJCShaXYZhangLJFangXL9-Nitrocamptothecin nanostructured lipid carrier system: in vitro releasing characteristics, uptake by cells, and tissue distribution in vivoYao Xue Xue Bao20054097097516499078

- EspositoMFantinMMDrechslerLSolid lipid nanoparticles as delivery systems for bromocriptinePharm Res2008251521153018172580

- QuanDQCuiGHDongHJRuanJXTissue distribution and antiinflammatory activity of dexamethansone acetate incorporated in lipid emulsionJ Chin Pharm Sci2001109093

- LinHMTsengHCWangCJLinJJLoCWChouFPHepatoprotective effects of Solanum nigrum Linn extract against CCl4-iduced oxidative damage in ratsChem Biol Interact200817128329318045581

- ParkOJeongWWangLDiverse roles of invariant natural killer T cells in liver injury an fibrosis induced by carbon tetrachlorideHepatology2009491683169419205035

- FriedmanSLMolecular regulation of hepatic fibrosis, an integrated cellular response to tissue injuryJ Biol Chem200027542247225010644669

- HuangQZouDJGuoZREffects of dexamethasone on the cultured retroocular fibroblast stimulated by cytokinesChin J Endocrinol Metab200016224227

- HalilEHayrettinOHulyaOHuseyinBDose-related effects of dexamethasone on liver damage due to bile duct ligation in ratsWorld J Gastroenterol2006125379538316981272

- MuYLiuPDuGAction mechanism of Yi Guan Jian Decoction on CCl4 induced cirrhosis in ratsJ Ethnopharmacol2009121354218996463