Abstract

Background

In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that metallic implants coated with nano hydroxyapatite (HA) reduce the time needed for complete osseointegration compared to metallic implants coated with conventional or micron-sized HA. Moreover, due to their biologically inspired nanometer dimensions, amphiphilic peptide nanoparticles (APNPs) can also promote osteoblast attachment and enhance other cell functions if used as a coating material. Coatings made of HA and APNPs could improve osteoblast functions, but have never been tested.

Purpose

The objective of this study was to prepare coatings of nanocrystalline HA and APNPs on poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (pHEMA) coatings in order to improve osteoblast (bone-forming cells) adhesion and cell density.

Methods

HA was synthesized by a wet chemical process. Coatings were synthesized with different conditions and components.

Results

X-ray diffraction infrared spectroscopy, transmission electron microscopy, and electron diffraction showed that nanocrystalline HA was synthesized with an expected nano size and shape distribution but with low impurities. pHEMA hydrogels with HA and APNPs increased osteoblast densities after 3 days compared to controls.

Conclusion

Since cell proliferation is a prerequisite function for bone formation, these results imply that the current materials should be tested for a wide range of orthopedic applications.

Introduction

Although metallic implants, especially titanium and its alloys, have high tensile and compressive strength, high corrosion resistance, and high biocompatibility, they do not tend to promote the regeneration of bone at their surfaces and they do not show an ability to support osseointegration over the long term.Citation1–Citation7 These metallic implants show high failure rates after 10–15 years of implantation. For instance, in the United States, 11% of hip replacements and 8% of knee replacements required revision in 2003.Citation8 For this reason, researchers have developed strategies for the modification of the surfaces of metallic implants in order to promote osseointegration.Citation1–Citation4,Citation9 An alternative to improve osseointegration and to reduce the wear of bone implants is to apply a surface coating with materials that are similar to those found in natural bone. Calcium phosphates seem to be good candidates for this purpose, as 65% of the mineral phase of bone is composed of Ca5(PO4)3(OH) (hydroxyapatite [HA]), a calcium phosphate; however, only some calcium phosphates are useful for this purpose, since its solubility increases when its Ca/P ratio is reduced.Citation10–Citation12

Fully crystalline HA is considered the best option to coat metallic implants.Citation1,Citation13–Citation15 Several studies have shown that implants coated with HA improved osseointegration compared to non-coated implants.Citation1,Citation3 Because nanomaterials possess enhanced physical properties (such as surface reactivity, surface area, and mechanical properties) compared to micron-structured materials (for instance, mechanical properties depend on the amount of defects and this amount is reduced when crystal size is reduced) and that HA present in the human body is nanometric, researchers have widely studied the use of nano HA to coat metallic implants.Citation8,Citation16 Nano HA has shown excellent cytocompatibility properties with osteoblasts. Moreover, in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated significant improvements when metallic prostheses are coated with nanocrystalline HA. For example, an in vivo study showed that titanium implants coated with nano HA took only 2 weeks to completely osseointegrate, whereas those implants covered with conventional HA took over 8 weeks.Citation8 Yet, despite such promise for the use of HA as a coating material to improve orthopedic implant efficacy, there have been issues with the methods used to coat HA, such as plasma spray deposition where small changes in temperature can cause large variations in chemistry, crystallinity, and so on to influence bone formation.

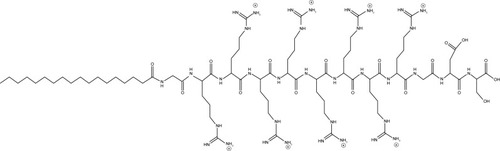

On the other hand, amphiphilic peptide nanoparticles (APNPs) are non-viral gene delivery vectors which can self-assemble into stable spherical micelles or fibrous structures with hydrophilic shells and hydrophobic cores with aqueous solutions.Citation17 APNPs contain the peptide arginine–glycine– aspartic acid (RGD) which not only promotes cell attachment but enhances other cell functions such as cell proliferation. We, thus, hypothesized that coating biomaterials with RGD-containing peptides can be a good strategy for controlling the cell material interface and achieving a bioactive implant.Citation18 Moreover, due to their surface energetics, APNPs can improve interactions with HA to provide for an improved metallic coating.

The aim of this study was to promote osteoblast proliferation, a necessary first step to osseointegration; for this, it is desired to obtain poly 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (pHEMA) coatings with nano HA and APNPs. In this way, this study was the first to determine whether HA/APNPs should be further studied as a novel orthopedic coating material.

Experimental

Synthesis of HA

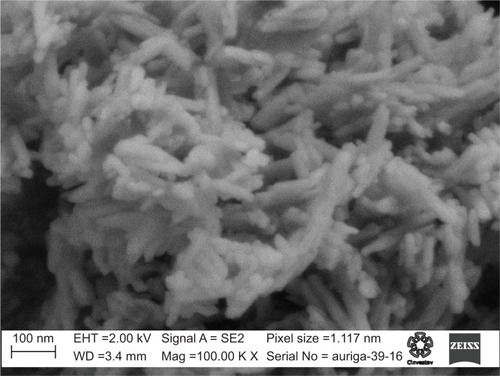

A precipitation method was used to synthesize HA, since this is an easy method to set up and operate, and mimics the biomineralization process of bone.Citation8 Briefly, 100 mL of a 0.65 M hydrogen ammonium phosphate (JT Baker, Center Valley, PA, USA) solution was mixed with 1,137.5 mL of deionized water (dH2O) while 150 mL of ammonium hydroxide (JT Baker) was used to adjust the pH of the solution to around 10. About 135 mL of a 1 M calcium nitrate tetrahydrate (Fermont, Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, Mexico) solution was slowly dripped into the above mixture. Precipitation continued for 10 minutes at room temperature. The solution was then centrifuged and rinsed with dH2O. The precipitate was finally dried at ~80°C for several hours. This process was repeated several times to obtain the HA needed to prepare the hydrogels. HA was sterilized with UV radiation for 30 minutes. shows a micrograph of the HA obtained demonstrating the characteristic nanometric features found in other studies.Citation8

Synthesis of APNPs

APNPs were prepared as previously described.Citation19 shows the chemical structure of the APNPs. APNPs were sterilized for 30 minutes with UV radiation.

HA characterization

HA powders were characterized by X-ray diffraction (Rigaku Smart Lab, Tokyo, Japan), infrared spectroscopy, transmission electron microscopy (JEOL JEM-2010; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan), and electron diffraction (JEOL JEM-2010; JEOL) following standard methods.

Substrate preparation

Sixteen Ti6Al4V samples of 1×1 cm were cut from a tempered Ti6Al4V foil (Goodfellow, Huntingdon, UK) and then polished with 240, 320, 400, 600, and 1,000 grit sandpaper.

Synthesis of coatings

A 70% (v/v) hydroxyethyl methacrylate monomer solution (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA) in water was used to prepare pHEMA coatings on Ti substrates. For the samples incorporated with nanoparticles, HA, APNPs, or both HA and APNPs were added to the monomer solution and sonicated for 15 minutes at room temperature. The final concentrations of HA nanoparticles and APNPs were 14 and 0.5 mg/mL, respectively. Monomer solutions were sonicated for another 30 minutes followed by the addition of 5 mg/mL azobisisobutyronitrile initiator. Ti substrates were pre-heated at 180°C for 30 minutes. Next, 20 µL of a freshly prepared monomer solution was added onto each substrate and heated at 180°C to allow for polymerization. The coated Ti substrates were washed in deionized water intensively to remove all of the unreacted initiator, sterilized with 70% ethanol, and dried under UV radiation after being washed with PBS (pH 7.4).

Osteoblast cell density assay

The human fetal osteoblast cell line (hFOB, ATCC® CRL 11372™) was used to evaluate osteoblast responses to the coated Ti substrates. The hFOB cells were cultured with Osteoblast Growth Medium (PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany) supplemented with 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 34°C and 5% CO2. In all experiments, cells with passage numbers 4–7 were used. Before experiments, the sterile Ti substrates coated with pHEMA were pre-soaked in cell culture media for 30 minutes at 34°C. The hFOB cells were then seeded onto the substrates at 5×104 cells/cm2. Cells were incubated for 3 days to allow for adhesion and growth onto substrates while cell culture medium was replaced every 48 hours. The MTS cell viability assay kit (Promega Corporation, Fitchburg, WI, USA) was used to determine cell densities. At the end of incubation, the Ti substrates with cells were washed with PBS and incubated with 1 mL of cell medium mixed with 200 µL of the MTS reagent. After the samples were incubated for 3 hours, the absorbance of the culture supernatant in each sample was taken and measured at a wavelength of 490 nm by a spectrophotometer (SpectraMax M3; Molecular Devices LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). To estimate the cell numbers in each well, a standard curve expressing the linear correlation between different cell densities and ODs (RCitation2>0.95) was plotted, and the cell numbers were determined with this standard curve from the OD490 value recorded for each sample.

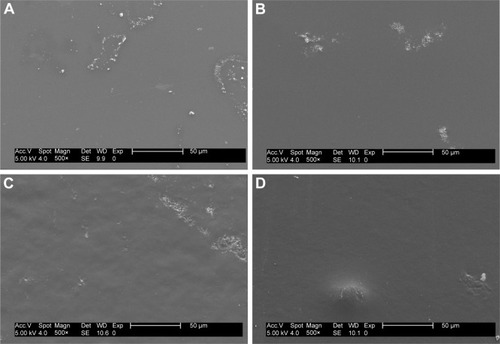

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images

An SEM (PHILLIPS/XL30-ESEM, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) was used to obtain surface micrographs from the cell experiments above including coatings with pHEMA, coatings with pHEMA and HA, coatings with pHEMA and APNPs, and coatings with pHEMA, HA, and APNPs.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean, and a two-tailed Student t-test was used to evaluate the differences between means, with P<0.05 being considered statistically significant.

Results

HA results

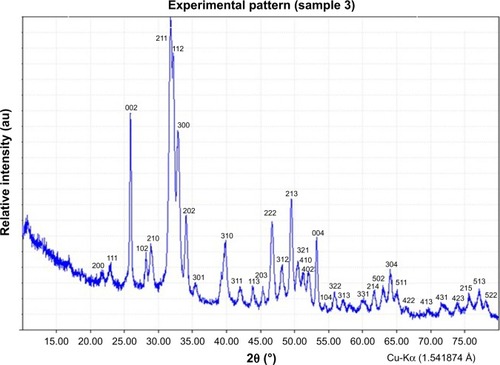

shows the X-ray diffraction pattern obtained for the synthesized HA.Citation8

Figure 3 XRD pattern of the synthesized HA.

Abbreviations: XRD, X-ray diffraction; HA, hydroxyapatite.

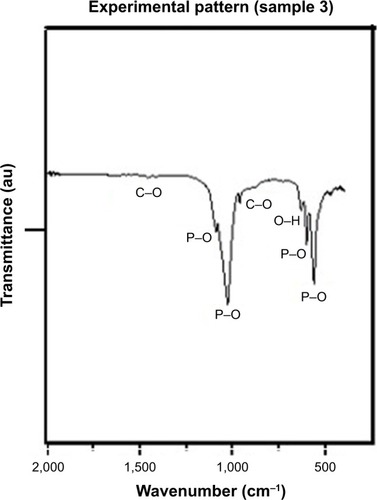

shows that all the peaks from the sample pattern match with those of the 09-0432 JCPDS diffraction card provided by the International Center for Diffraction Data (ICDD). It is seen that some peaks have different intensities with respect to those in the ICDD pattern. Moreover, positions of the peaks did not differ from those in the ICDD pattern. Based on these observations, it can be concluded that the sample contained HA; although there were some impurities (C–O bond, ) in the HA, it did not have size and shape distortion. shows the infrared spectrum obtained for the synthesized HA again showing expected peaks and confirming results of other studies.Citation8

In , P–O and O–H bonds, which were present in HA, were identified. C–O bonds were also identified and could be present due to the interaction of CO2 and the compounds present in the reaction.

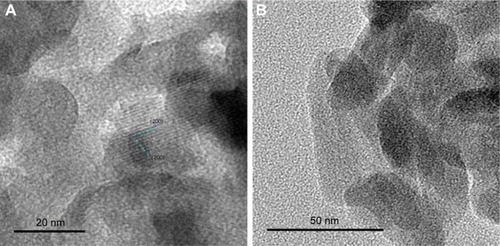

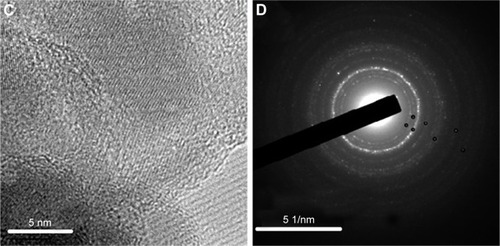

shows the transmission electron microscope (TEM) images as well as the electron diffraction pattern obtained for the synthesized HA. shows that the sample grew in the (200) preferential direction, while shows that nanocrystals were obtained, whose dimensions were about 50 nm in length and 30 nm in width. shows a TEM image and the electron diffraction pattern obtained from it.

Figure 5 TEM images of (A–C) synthesized HA. (D) Electron diffraction pattern of HA.

Abbreviations: TEM, transmission electron microscope; HA, hydroxyapatite.

shows the indexation of the electron diffraction pattern shown in again with the expected results.

Table 1 Indexation of electron diffraction pattern

shows that the interplanar distances obtained from the electron diffraction pattern () match those obtained from the ICDD; for this reason, it was concluded that the sample contains HA.

APNP characterization

APNPs were characterized as previously described.Citation19

SEM images

The micrographs obtained are shown in . It can be seen that the morphology of the samples showed plain areas and small areas with bumps and small particles; however, at these magnifications, the morphology did not change significantly from sample to sample.

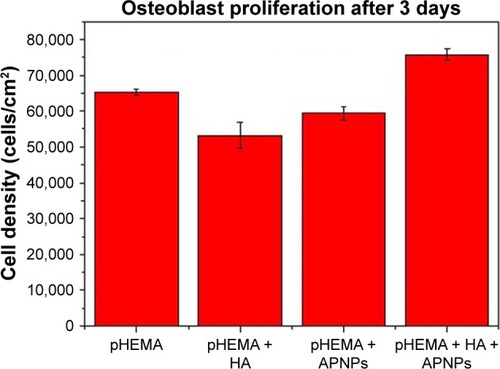

Osteoblast cell density results

Results from the osteoblast density tests provided the first evidence of greater osteoblast density on pHEMA coatings with nanocrystalline HA and APNPs compared to coatings with plain pHEMA, pHEMA and HA, and pHEMA and APNPs (). The osteoblast density on the coatings with pHEMA, nanocrystalline HA, and APNPs increased 17%, 38%, and 25% compared to coatings with plain pHEMA, pHEMA and APNPs, and pHEMA and HA, respectively.

Discussion

This study showed for the first time that simply adding both nano HA and APNPs to a common hydrogel, pHEMA, significantly increases osteoblast densities. Interestingly, when adding both of the components individually (either nano HA or APNPs), osteoblast densities did not increase. Thus, there is something certainly unique that needs to be further studied concerning the interactions between nano HA and APNPs to promote osteoblast attachment and growth necessary for bone growth to occur. Although not determined in this study, it is plausible that APNPs by themselves were embedded into pHEMA and, thus, hidden from osteoblasts to promote their adhesion and growth via their RGD peptide sequence. Furthermore, HA nanoparticles may have been exposed, but not in high enough concentration to promote osteoblast densities as seen in other studies.Citation8 Yet, collectively the HA nanoparticles may have been coated with APNPs and thus helped surface exposure of RGD (and bioactivity) in the APNPs to promote osteoblast densities. Clearly, the mechanism for the greater osteoblast densities needs to be further elucidated in order to optimize such results. Additional mechanisms may involve alterations in surface energy which can change initial protein adsorption important for promoting osteoblast adhesion events. This has been a common mechanism elucidated when adding nanoparticles to hydrogels which leads to increased hydrophilicity and consequently greater vitronectin adsorption, a protein commonly associated with greater osteoblast adhesion.Citation8 Furthermore, it would be interesting to examine how many other hydrogels, nano HA, and APNPs can be added to promote the functions of osteoblasts. Nonetheless, it is clear that the present addition of only nano HA and APNPs to pHEMA represents a simple way to promote osteoblast densities on a popular injectable tissue engineering material.

Conclusion

In summary, HA was synthesized by a precipitation method and characterized by several techniques. The present study demonstrated that nanocrystalline HA was obtained. Moreover, several coatings with different conditions were obtained. There was a statistical difference between osteoblast cell density obtained for coatings prepared with pHEMA, HA and APNPs compared to the osteoblast cell density obtained for the rest of the coatings. Creating a biomimetic coating made of pHEMA hydrogels with HA and APNPs is a promising idea to improve osteoblast density which deserves further investigation to perhaps ultimately increase the life expectancy of an orthopedic implant.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by CONACYT. We would like to thank the staff of CINVESTAV Zacatenco, LIDTRA CINVESTAV Queretaro, Northeastern University, and Mogel Fluidos SA de CV for providing materials for synthesis as well as equipment for analyzing the data.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- XiaZYuXWeiMBiomimetic collagen/apatite coating formation on Ti6al4V substratesJ Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater2011100B87188110.1002/jbm.b.31970

- PanMKongXCaiYYaoJHydroxyapatite coating on the titanium substrate modulated by a recombinant collagen-like proteinMater Chem Phys2011126381181710.1016/j.matchemphys.2010.12.037

- CiobanuGCiobanuOInvestigation on the effect of collagen and vitamins on biomimetic hydroxyapatite coating formation on titanium surfacesMater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl20133331683168810.1016/j.msec.2012.12.08023827624

- TangSTianBGuoY-JZhuZ-AGuoY-PChitosan/carbonated hydroxyapatite composite coatings: fabrication, structure and bio-compatibilitySurf Coat Technol201425121021610.1016/j.surfcoat.2014.04.028

- AskalBKomMTosunHBDemirelMInfluence of micro- and nanohydroxyapatite coatings on the osteointegration of metallic (Ti6Al4V) and bioabsorbable interferences screws: an invo studyEur J Orthop Surg Traumatol201424581381910.1007/s00590-013-1236-823689912

- MacchiRLMateriales Dentales Buenos AiresArgentinaEditorial Panamericana2007390397

- CraigRGPowersJMWatahaJCDental MaterialsMichiganMosby2000

- ZhangLChenYRodriguezJFenniriHWebsterTJBiomimetic helical rosette nanotubes and nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium for improving orthopedic implantsInt J Nanomedicine20083332333318990941

- YaszemskiMJTrantoloDJLewandrowskiK-UHasirciVAltobelliDEWiseDLBiomaterials in OrthopedicsBoca RatonMarcel Dekker20041435

- RatnerBDHoffmanADSchoenFJLemonsJEBiomaterials ScienceSan DiegoElsevier Academic Press2004162167

- LeGerosRZCalcium Phosphates in Oral Biology and MedicineNew YorkKarger199112

- BeheriHHMohamedKREl-BassyouniGTMechanical and microstrcutre of reinforced hydroxyapatite/calcium silicate nanocomposites materialsMater Des20134446146810.1016/j.matdes.2012.08.020

- FernandezJGuilemanyJMGaonaMLa proyección térmica en la obtención de recubrimientos biocompatibles: ventajas de la proyección térmica por alta velocidad (HVOF) sobre la proyección térmica por plasma atmosférico (APS)Biomecánica20051311639 Spanish

- FawcettDWCompendio de HistologíaMadridMcGraw Hill19997485

- KokuboTBioceramics and Their Clinical ApplicationsCambridgeWoodhead Publishing Materials2008367386

- PooleCPOwensFJIntroducción a la NanotecnologíaBarcelonaEditorial Reverté200780

- ChenJ-XWangHYQuanC-YXuX-DZhangX-ZZhuoR-XAmphiphilic cationic lipopeptides with RGD sequences as gene vectorsOrg Biomol Chem201083142314810.1039/c003538f20480122

- SchaffnerPDardMMStructure and function of RGD peptides involved in bone biologyCell Mol Life Sci200360111913212613662

- ChangRSunLWebsterTJSelective inhibition of MG-63 osteosarcoma cell proliferation induced by curcumin-loaded self-assembled arginine-rich-RGD nanospheresInt J Nanomedicine2015103351336510.2147/IJN.S7875626005346