Abstract

A simple single-stage approach, based on the hydrothermal technique, has been introduced to synthesize reduced graphene oxide/titanium dioxide nanocomposites. The titanium dioxide nanoparticles are formed at the same time as the graphene oxide is reduced to graphene. The triethanolamine used in the process has two roles. It acts as a reducing agent for the graphene oxide as well as a capping agent, allowing the formation of titanium dioxide nanoparticles with a narrow size distribution (~20 nm). Transmission electron micrographs show that the nanoparticles are uniformly distributed on the reduced graphene oxide nanosheet. Thermogravimetric analysis shows the nanocomposites have an enhanced thermal stability over the original components. The potential applications for this technology were demonstrated by the use of a reduced graphene oxide/titanium dioxide nanocomposite-modified glassy carbon electrode, which enhanced the electrochemical performance compared to a conventional glassy carbon electrode when interacting with mercury(II) ions in potassium chloride electrolyte.

Introduction

Graphene is a monocrystalline graphitic film a few atoms thick and is stable under ambient conditions. The physical dimension of the film’s thickness ensures the electronic structure of the material is two-dimensional. Moreover, there is a small overlap between the valence and conduction bands, and graphene exhibits semimetal behavior. With the addition of a gate electrode, electron and hole concentrations in the channel can be as high as 1013 cm−3 with mobility at room temperature in the order of 10,000 cm2V−1 s−1. These results make graphene an ideal candidate for the next generation of electronic devices.Citation1 In addition, graphene has extremely good mechanical and thermal properties and thus has potential application over a wide variety of uses such as composite materials, fuel cells, batteries, chemical detectors, and solar cells.Citation2–Citation11 Moreover, the integration of graphene with inorganic nanoparticles allows the properties of the nanocomposite to be engineered for specific applications, which is rapidly becoming a research trend as the nanocomposites are able to exhibit properties that are not found in the individual components.Citation6,Citation12–Citation18

Nanocrystalline titanium dioxide (TiO2) is a promising candidate for solar energy conversion applications such as photocatalysis, photochromism, and photovoltaics because of its unique optical and electrical properties.Citation19 It is widely used in applications such as hydrogen production,Citation20,Citation21 gas sensors,Citation22,Citation23 photocatalytic activities,Citation24,Citation25 and dye- sensitized solar cellsCitation26,Citation27 because of its relative high efficiency and high stability.

The microbiocidal effects of TiO2 photocatalytic reactionsCitation28 clearly have pharmacological applications and TiO2 photocatalytic reactions have been used to kill a wide spectrum of organisms including bacteria,Citation29 viruses,Citation30 fungi,Citation31 cancer cells,Citation32 and algal toxins.Citation33 In addition, antibacterial activity against four common human pathogens, namely Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus, has also been demonstrated.Citation34 In addition, the oxidizing power of TiO2 when under irradiation of ultraviolet (UV) light in either water or an oxygen-rich environment means that irradiated TiO2 can be used in waste processing because of its ability to decompose and/or oxidize most organic and/or inorganic compounds.Citation36,Citation37 Interestingly, its high chemical stability and nontoxicity also makes TiO2 biocompatible, and it is used in many cosmetic products and as an alternative material for improving antimicrobial properties. For example, TiO2 nanoparticles have been added to dental acrylic resins to improve the color.Citation35

The challenge when developing convenient and effective processing technologies for the fabrication of graphene nanocomposites is the prevention of the restacking and/or agglomeration of the graphene sheets caused by the changes in the Van der Waals interactions due to the presence of metal oxide particles like TiO2.Citation38,Citation39 Recently, graphene/TiO2 nanocomposites have been synthesized using technologies such as atomic layer depositionCitation40 and electron beam irradiation. Citation41 Although successful, these methods are probably not commercially viable since the processes require a sixstep sequence with heat treatment at various temperaturesCitation40 or pretreated grapheneCitation41 as a raw material. Furthermore, other reported techniques that use hazardous chemicals, such as hydrazine hydrate, create dangerous by-products such as hydrogen fluoride.Citation42 Other reported problems in the formation of graphene nanocomposites include the lack of discrete nanocrystalline TiO2 particles before calcinationCitation43 and agglomeration of the TiO2 particles.Citation44,Citation45

In this paper, a one-step hydrothermal route for the preparation of graphene/TiO2 nanocomposites using graphene oxide (GO) and titanium isopropoxide as starting materials with the addition of triethanolamine (TEA) is reported. The hydrothermal technique was chosen because it is a “soft solution chemical processing” technique, which provides an easier way to control particle size, particle morphology, microstructures, phase composition, and surface chemical properties with adjustments in experimental parameters such as temperature, pressure, duration of process, and pH value of solution.Citation46–Citation49 This one-step hydrothermal method is convenient and safe, and with the addition of TEA to the solution, the process provides a route to manufacture graphene/TiO2 nanocomposites where the TiO2 nanoparticles are discrete with no agglomeration of the particles. This is not the first time a single-step hydrothermal technique has been reported; however, there are significant differences between the process reported in this paper and those already published. Shen et al reported an “intrinsically pure process,” which utilized only water and glucose.Citation50 However, their sample prior to hydrothermal treatment contained ammonium chloride, ethanol, glucose, and ammonium hydroxide.Citation50 In the method reported here, only TEA and ethanol were added. Other reported one-step hydrothermal processing studies used ultrasonication to obtain a well-dispersed suspension of GO and TiO2. This step was omitted in the current work.

The objective of this work was to study the influence of the hydrothermal temperature on the crystallinity, size distribution, thermal stability, and electrochemical performance of reduced GO (RGO)/TiO2 nanocomposites. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the effect of TEA and reaction temperature on the formation of RGO/TiO2 nanocomposites has not been previously reported.

Material and methods

Materials

Graphite 3061 and titanium isopropoxide (99%) were purchased from Asbury Graphite Mills Inc (Asbury, NJ) and Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium), respectively; TEA and potassium permanganate were obtained from R&M Chemicals (Systerm, Malaysia). The other materials – sulfuric acid, phosphoric acid, hydrogen peroxide, and ethanol – were purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Unless otherwise specified, all the reagents and materials involved were used as received without further purification. Deionized water (resistivity ≥18 MΩ) was used during the experimental process.

Synthesis of GO

GO was synthesized via the simplified Hummers method in which a 9:1 sulfuric acid:phosphoric acid (360:40 mL) solution was prepared, into which 3 g of graphite was added. Citation51,Citation52 Potassium permanganate (18 g) was gradually added and the solution was left to oxidize for 3 days whilst being continuously stirred. After 3 days, the resulting solution was cooled to room temperature and poured onto ice (~400 mL) along with 27 mL of 30% hydrogen peroxide. The solution was centrifuged (CR21GIII;Hitachi, Japan) and washed three times with 1 M hydrogen chloride and six times with water. The final solution, the GO dispersion, was light brown in color.

Synthesis of RGO/TiO2

Titanium isopropoxide (3.72 mL) was added into 3.32 mL of TEA in a 25 mL volumetric flask (Favorit, PLT Scientific Sdn. Bhd) producing a titanium(IV) ionic (Ti4+) solution with a concentration of 0.50 M. In order to form the GO/TiO2 solution, 10 mL of 1 mg/mL of GO solution was added into a water:ethanol mixture (1:14) mL with continuous stirring. After that, 3 mL of Ti4+ solution was added and the mixture stirred for 24 hours at room temperature to obtain a homogeneous suspension. The mixture was placed in a custom made Teflon-lined autoclave and heated to 120°C for 24 hours. Two other samples were prepared by an identical procedure except for the final autoclave reaction temperature (150°C and 180°C). The samples were labeled as 120 RGO/TiO2, 150 RGO/TiO2, and 180 RGO/TiO2, with the number signifying the reaction temperature. The black precipitates were washed three times with ethanol, centrifuged at 13,000 g for 10 minutes, and dried at 60°C. Pure TiO2 samples were also prepared using the same procedure; these samples are denoted as 120 TiO2, 150 TiO2, and 180 TiO2. RGO was also synthesized in the absence of titanium isopropoxide under the same conditions at 180°C.

Characterization

The atomic structure of the samples was investigated by X-ray diffraction (XRD, D5000, Siemen) (XRD) using copper Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) at a scan rate of 0.02 degrees s−1. This was complemented by transmission electron microscopy (CM12; Philips) operated at 100 kV, which allowed an image of the nanoparticles and graphene flakes to be acquired. The chemical stability was investigated using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (Q500; TA Instruments, New Castle, DE) and the bond structure investigated using UV-visible spectroscopy with a scan rate of 240 nm/mm (Evolution 300; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The electrochemical performance was assessed using three-electrode cyclic voltammetry with a silver/silver chloride 3 M sodium chloride reference electrode and a platinum counter electrode (CV-50W voltammetric analyzer; Bioanalytical Systems Inc, West Lafayette, IN).

Electrochemical performance

The working electrode was 3 mm in diameter and made from a glassy carbon electrode (GCE). Before modification, the bare GCE was polished with alumina slurry on microcloth pads (MetaServ 250, Buehler) and thoroughly rinsed with distilled water between each polishing step. The final cleaning step was successive washes with distilled water and anhydrous alcohol. The modified electrode was made by tapping the bare GCE onto the sample ten times successively. Citation53 The cell electrolyte was formed by mixing 10 mL of 0.1 M of potassium chloride with 190 μL of 1.0 mM mercuric chloride analyte. Once all three electrodes were immersed into the supporting electrolyte solution, nitrogen gas was bubbled through the solution for 15 minutes to remove any dissolved oxygen before the voltammogram was recorded. The potential range was checked before any readings on the voltammogram were recorded. All the voltammetric experiments were referred at an ambient temperature of 25°C ± 2°C.

Results and discussion

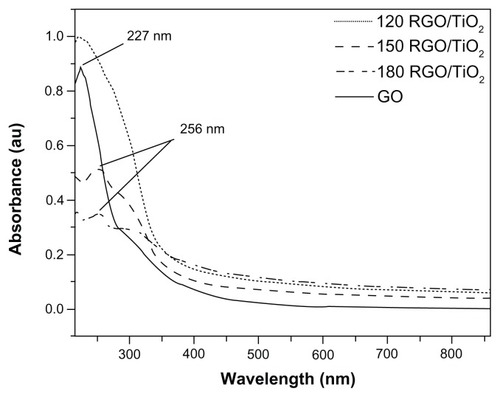

UV-visible absorption spectroscopy measurements for RGO/TiO2 nanocomposites are shown in and indicate the degree of reduction in the increase of GO as the reaction temperature increased. For pure GO, there was a peak at about 227 nm and a shoulder at around 300 nm. The peak at 227 nm is assigned to the pi to anti-pi (π → π*) transition of the aromatic carbon–carbon bonds and the shoulder at 300 nm to the n to anti-pi (n → π*) transitions of the carbon = oxygen bonds.Citation54 The 120 RGO/TiO2 sample had a broad peak centered at 227 nm and a shoulder at approximately 300 nm. There was no evidence of a peak at 256 nm, which is a characteristic of graphene and is attributed to the aromatic carbon = carbon bonds. For the 150 RGO/TiO2 and 180 RGO/TiO2 samples, the peak at 227 nm right-shifted to 256 nm. This represents the partial restoration of the pi-conjugation network of the sample as a result of the hydrothermal and chemical reduction process. All the RGO/TiO2 nanocomposite samples showed typical absorption of TiO2 with an absorption edge of around 360 nm, while the 180 RGO/TiO2 sample showed a higher absorption edge of around 375 nm.

Figure 1 Ultraviolet-visible absorption spectra of reduced graphene oxide/titanium dioxide nanocomposites and graphene oxide.

Note: 120, 150, and 180 indicate the reaction temperature.

Abbreviations: GO, graphene oxide; RGO/TiO2, reduced graphene oxide/titanium dioxide nanocomposite.

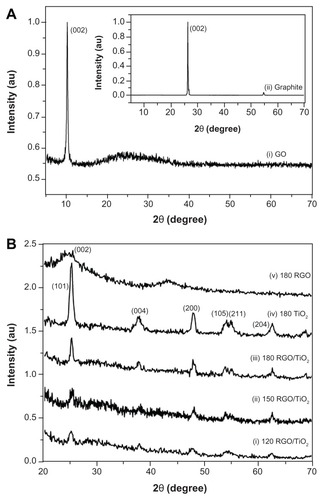

show the XRD patterns of the graphite, GO, RGO, pure TiO2, and RGO/TiO2 nanocomposites. The dominant diffraction peak centered at around eleven degrees in the XRD pattern of GO corresponded to reflection from the (002) plane,Citation55,Citation56 whilst for raw graphite this reflection occurred at around 26 degrees and was very intense. For the RGO samples, the (002) reflection peak was broad and was centered at around 25 degrees. The broad diffraction peak of RGO indicates poor ordering of the sheets along the stacking direction, which implies the sample was comprised mainly from single or only a few layers of RGO.Citation57 The band at 43 degrees corresponded to the turbostratic band of disordered carbon materials.Citation58 No diffraction peak attributable to reflections from graphite crystal planes was observed, which suggests the stacking of the RGO sheets remained disordered and were not stacked together to form a detectable graphite structure.

Figure 2 X-ray diffraction patterns of (A) graphite and graphene oxide and (B) reduced graphene oxide, titanium dioxide, and reduced graphene oxide/titanium dioxide nanocomposites.

Note: 120, 150, and 180 indicate the reaction temperature.

Abbreviations: GO, graphene oxide; RGO, reduced graphene oxide; RGO/TiO2, reduced graphene oxide/titanium dioxide nanocomposite; TiO2, titanium dioxide.

In addition to the peaks attributable to carbon-based compounds, the XRD spectrum contained peaks which have been assigned to reflections from the anatase phase of tetragonal TiO2 with lattice constants of a = 3.7892 Å, b = 3.7892 Å, c = 9.5370 Å, and β = 90.0000 (JCPDS 71-1167). The diffraction peaks can be indexed as reflections from the (101), (004), (200), (105), (211), and (204) planes, respectively. There was no evidence for the other phases of TiO2 being present. Comparing the 120 RGO/TiO2 and the 180 RGO/TiO2 samples, there was an increase in peak intensities of the peaks attributed to the reflections from TiO2, which suggests the formation of larger TiO2 crystallites and enhancement of the TiO2 crystallization process.Citation59 Full width at half maximum of the TiO2 (101) reflection for the 120 RGO/TiO2, 150 RGO/TiO2, and 180 RGO/TiO2 samples was 1.1595 degrees, 0.9832 degrees, and 0.6378 degrees, respectively. Since the full width at half maximum is inversely proportional to the nanocrystal size (Scherrer equation), this result further confirms the hypothesis that higher hydrothermal temperatures produce greater TiO2 crystallization. The presence of graphene cannot be confirmed in the XRD spectra for the RGO/TiO2 samples because there was no peak in the XRD spectrum that can be attributed to graphene. The most likely explanation is that the relatively weak and broad characteristic peak of graphene at 24.5 degrees was masked by the strong (101) TiO2 reflections at 25.4 degrees.Citation60

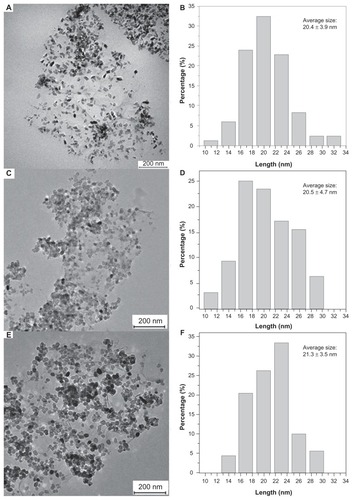

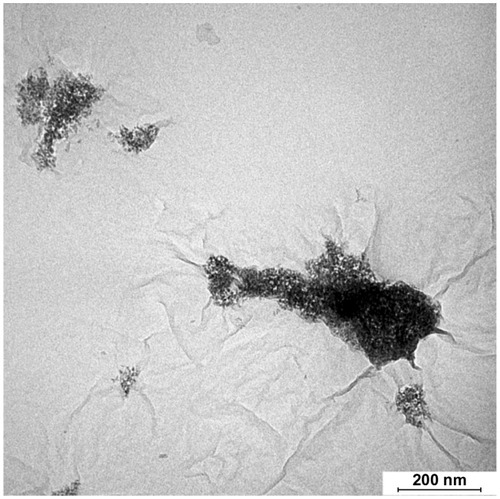

Transmission electron micrographs of the samples are shown in along with the size distributions of the TiO2 nanoparticles. The nanoparticles were distributed uniformly on the basal plane of RGO nanosheets. The nanoparticles appeared to have a rounder shape in the 180 RGO/TiO2 sample when compared to the 120 RGO/TiO2 sample. The average size of the nanoparticles for the 120 RGO/TiO2, 150 RGO/TiO2, and 180 RGO/TiO2 was 20.4 ± 3.9 nm, 20.5 ± 4.7 nm, and 21.3 ± 3.5 nm, respectively. The histograms of the size distribution of the nanoparticles in the nanocomposites are exhibited on the right hand side of . The size distribution of the TiO2 nanoparticles was narrower when the hydrothermal temperature increased. This trend agrees with the observation of more crystallized, round shaped, and homogeneous particles at 180°C compared to the less crystallized, amorphous, and heterogeneous particles at 120°C. The role of TEA in the formation of the nanocrystals can be clearly seen in which shows a transmission electron micrograph of the RGO/TiO2 sample synthesized under the same conditions at 180°C but without the presence of TEA. The TiO2 nanoparticles agglomerated and did not distribute homogenously on the RGO sheet.

Figure 3 (A, C and E) Transmission electron micrograph and (B, D and F) histogram of reduced graphene oxide/titanium oxide nanocomposites at (A and B) 120°C, (C and D) 150°C, and (E and F) 180°C.

Figure 4 Transmission electron micrograph of reduced graphene oxide/titanium oxide nanocomposite synthesized without triethanolamine.

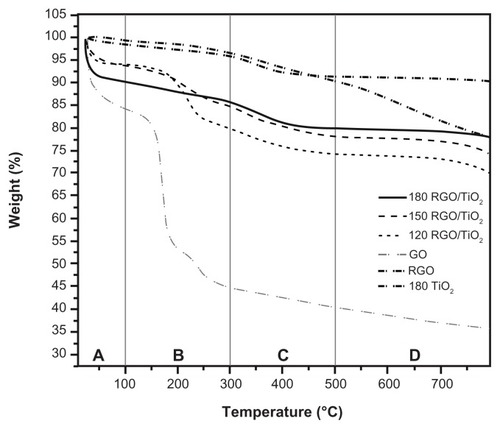

The successful decoration of TiO2 nanoparticles on RGO is also reflected in the TGA curves (). The TGA curves for all the nanocomposites had four distinct regions (A, B, C, and D). In the region up to 100°C (region A), the sample weight loss was caused by the resorption of physisorbed water. Between 150°C–300°C (region B), the weight loss was a result of the decomposition of labile oxygen groups like carboxylate, anhydride, or lactone groups. Region C occurred between 300°C–500°C and was associated with the removal of more stable oxygen groups such as phenol, carbonyl, and quinine. Above 500°C (region D), high temperature pyrolysis of carbon skeleton occurred.Citation50 GO displayed a drastic weight loss (40% of its original weight) in region B caused by the decomposition of labile oxygen-containing functional groups such as epoxy and hydroxyl groups. There was a similar loss of weight for the RGO, but the change was not so big. This result indicates that most of the GO oxygen-containing functional groups were reduced during the hydrothermal process, thereby increasing the thermal stability of the RGO.Citation61 For the nanocomposites in region B, the percentage of weight loss decreased with hydrothermal temperature. Specifically, the 120 RGO/TiO2, 150 RGO/TiO2, and 180 RGO/TiO2 samples lost 14.1%, 7.9%, and 3.5% of their weight, respectively. This result indicates that the 180 RGO/TiO2 sample had the least amount of labile oxygen-containing functional groups attached to the surface. It also further indicates that a low hydrothermal temperature (120°C) was unable to reduce the oxygenous groups of GO in the nanocomposites efficiently.

Figure 5 Thermogravimetric analysis curves of graphene oxide, reduced graphene oxide, titanium dioxide, and reduced graphene oxide/titanium dioxide nanocomposites.

Note: 120, 150, and 180 indicate the reaction temperature.

Abbreviations: GO, graphene oxide; RGO, reduced graphene oxide; RGO/TiO2, reduced graphene oxide/titanium dioxide nanocomposite; TiO2, titanium dioxide.

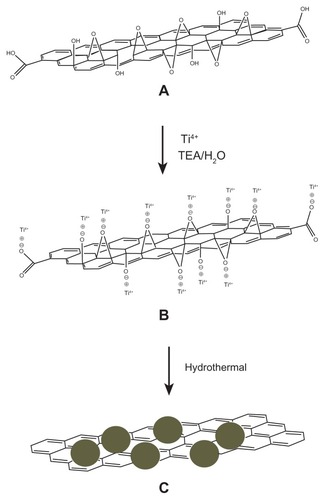

A plausible schematic formation of RGO/TiO2 is illustrated in . GO was mixed with Ti4+ in the presence of TEA. This provided a platform for electrostatic interaction between the negatively-charged oxide functional groups of GO and the positively-charged Ti4+ (). Nucleation occurred at the sites, which resulted in the growth of TiO2 nanoparticles on the two-dimensional graphene nanosheets during the hydrothermal process (). The narrow size distribution of the TiO2 nanoparticles embedded on the graphene nanosheets may be due to the critical control of the TEA molecules. GO was reduced to graphene due to the simultaneous presence of Ti4+, TEA, and hydrothermal treatment.

Figure 6 Schematic formation mechanism of the reduced graphene oxide/titanium dioxide nanocomposite. (A) Graphene oxide. (B) Electrostatic interaction between oxide functional groups of graphene oxide and titanium(IV) in the presence of triethanolamine. (C) Graphene decorated with titanium dioxide nanoparticles (filled circles) after hydrothermal treatment.

Abbreviations: H2O, water; TEA, triethanolamine; Ti4+, titanium(IV).

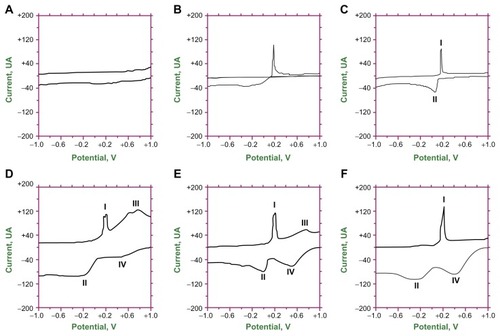

displays the electrochemical performance of the samples examined by cyclic voltammetry with a scan rate of 50 mV s−1. The background current behavior for bare GCE in potassium chloride supporting electrolyte with no mercury ions was almost flat and there were no oxidizing and reducing reactions (). On the other hand, the results for the bare GCE using the potassium chloride electrolyte containing mercury(II) ions (Hg2+) in potassium chloride resulted in a distinctive oxidizing peak current observed between +0.1 V and +0.2 V (peak I; ). The RGO-modified GCE in potassium chloride supporting electrolyte added with Hg2+ had an additional reductive peak between −0.2 and +0.2 V (peak II; ). The entire hydrothermally prepared RGO/TiO2-modified GCE had improved electrochemical performance, signifying an increase in sensitivity to the detection of Hg2+ (). The 150 RGO/TiO2-modified GCE exhibited additional oxidization reactions between +0.4 and +1.0 V (peak III) of all the samples. There were two distinct peaks. This oxidization reaction was in addition to the oxidative peak (peak I) seen in the RGO-modified GCE (). The sample also had a trough-like reductive peak (peak II), which shifted to a lower voltage by about 0.2 V, and there was a reductive shoulder between +0.2 and +0.8 V (peak IV). The 180 RGO/TiO2-modified GCE showed similar oxidative (peaks I and III) and reductive peaks (peaks II and IV; ). For the 120 RGO/TiO2-modified GCE, the two reductive peaks (peak II – which shifted by about 0.2 V to the left – and peak IV) were enhanced by approximately 40 μA () when compared to the 180 RGO/TiO2-modified GCE. The peaks most likely arose through the stepwise reduction of Hg2+ + e− ⇆ Hg+ and Hg+ + e− ⇆ Hg0. The oxidative peak (peak II) that was so pronounced in the 150 RGO/TiO2- () and 180 RGO/TiO2-modified GCE () was missing in the 120 RGO/TiO2-modified GCE. Among all the samples, the 120 RGO/TiO2-modified GCE possessed the best reducing reaction, which possibly makes it an efficient redox-recyclable material for the extraction of heavy element ions from wastewater.

Figure 7 Electrochemical analysis of (A) bare glassy carbon electrode in potassium chloride supporting electrolyte, (B) bare glassy carbon electrode, (C) reduced graphene oxide-modified glassy carbon electrode, and reduced graphene oxide/titanium dioxide nanocomposite-modified glassy carbon electrode at (D) 150°C, (E) 180°C, and (F) 120°C in potassium chloride supporting electrolyte and mercury(II) ionic solution.

Conclusion

TiO2 (with particle size of about 20 nm) decorated RGO with high uniformity and were successfully synthesized via a simple hydrothermal process using TEA as the coreducing agent and capping agent. This simplified method has great advantage over other published methods of producing graphene-decorated TiO2 nanoparticles. The method allows control of the particle size distribution through alteration of the hydrothermal temperature. This enables the properties of the nanocomposite to be tailored to a specific application, as demonstrated by the detection of mercury ions in the electrochemical cell where the redox peaks in the cyclic voltammetric depended on the hydrothermal reactor temperature. This synthesis method can be easily extended to the fabrication of other classes of RGO-based nanocomposites. The red-shift phenomenon in the UV analysis demonstrates the applicability of nanocomposites in photovoltaic and photocatalytic applications. The RGO/TiO2 nanocomposites demonstrated enhanced electrochemical performance for the detection of Hg2+, suggesting the possibility of using them for detection of the heavy metal.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the High Impact Research Grant (UM.C/625/1/HIR/030) from the University of Malaya, the High Impact Research Grant (UM.C/625/1/HIR/MOHE/05) from the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia, University of Malaya Research Grant (RG096-10AFR) and the Postgraduate Research Grant (UM.C/241/9) from the University of Malaya. BYS Chang would like to thank The Bright Sparks Unit of University of Malaya for the research incentives.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- NovoselovKSGeimAKMorozovSVElectric field effect in atomically thin carbon filmsScience2004306569666666915499015

- AleinerILEfetovKBEffect of disorder on transport in graphenePhys Rev Lett2006972323680123680417280222

- MeyerJCGeimAKKatsnelsonMINovoselovMIBoothTJRothSThe structure of suspended graphene sheetsNature20074467131606317330039

- NovoselovKSGeimAKMorozovSVTwo-dimensional gas of massless Dirac fermions in grapheneNature2005438706519720016281030

- SchedinFGeimAKMorozovSVDetection of individual gas molecules adsorbed on grapheneNat Mater200769965265517660825

- ZhangYTanYWStormerHLKimPExperimental observation of the quantum Hall effect and Berry’s phase in grapheneNature2005438706520120416281031

- NiZHWangHMKasimJGraphene thickness determination using reflection and contrast spectroscopyNano Lett2007792758276317655269

- SykesECSurface assembly: graphene goes undercoverNat Chem20091317517621378838

- IshigamiMChenJHCullenWGFuhrerMSWilliamsEDAtomic structure of graphene on SiO2Nano Lett2007761643164817497819

- BalandinAAGhoshSBaoWCalizoITeweldebrhanDMiaoFLauCNSuperior Thermal Conductivity of Single-Layer GrapheneNano Lett20088390290718284217

- KonathamDStrioloAMolecular design of stable graphene nanosheets dispersionsNano Lett20088124630464119367980

- YooEOkataTAkitaTKohyamaMNakamuraJHonmaIEnhanced electrocatalytic activity of Pt subnanoclusters on graphene nanosheet surfaceNano Lett2009962255225919405511

- ZhaoJPeiSRenWGaoLChengHMEfficient preparation of large-area graphene oxide sheets for transparent conductive filmsACS Nano2010495245525220815368

- ZhuJGraphene production: new solutions to a new problemNat Nanotechnol20083952852918772910

- KongBSGengJJungHTLayer-by-layer assembly of graphene and gold nanoparticles by vacuum filtration and spontaneous reduction of gold ionsChem Commun (Camb)2009162174217619360184

- ScheuermannGMRumiLSteurerPBannwarthWMulhauptRPalladium nanoparticles on graphite oxide and its functionalized graphene derivatives as highly active catalysts for the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reactionJ Am Chem Soc2009131238262827019469566

- YugeRZhangMTomonariMYoshitakeTIijimaSYudasakaMSite identification of carboxyl groups on graphene edges with Pt derivativesACS Nano2008291865187019206426

- YangXZhangXMaYHuangYWangYChenYSuperparamagnetic graphene oxide–Fe3O4 nanoparticles hybrid for controlled targeted drug carriersJ Mater Chem2009191827102714

- LeeSChoISLeeJHTwo-step sol-gel method-based TiO2 nanoparticles with uniform morphology and size for efficient photo-energy conversion devicesChem Mater201022619581965

- HongWSParkJHHanGYOptimization of conditions for hydrogen production from anodized TiO2 nanotube-based photoelectrochemical cellsJ Nanosci Nanotechnol20099127293729719908775

- SatoSWhiteJMPhotodecomposition of water over Pt/TiO2 catalystsChem Phys Lett19807218386

- HanCHHongDWHanSDGwakJSinghKCCatalytic combustion type hydrogen gas sensor using TiO2 and UV-LEDSens Actuators B Chem20071251224228

- ParkJAMoonJLeeSJKimSHZyungTChuHYStructure and CO gas sensing properties of electrospun TiO2 nanofibersMater Lett2010643255257

- ChenLTianJQiuHPreparation of TiO2 nanofilm via sol-gel process and its photocatalytic activity for degradation of methyl orangeCeram Int200935832753280

- YazawaTMachidaFKuboNJinTPhotocatalytic activity of transparent porous glass supported TiO2Ceram Int200935833213325

- DhasVMuduliSAgarkarSEnhanced DSSC performance with high surface area thin anatase TiO2 nanoleavesSolar Energy201185612131219

- RahmanMTajabadiFShooshtariLTaghaviniaNNanoparticulate hollow TiO2 fibers as light scatterers in dye-sensitized solar cells: layer-by-layer self-assembly parameters and mechanismChemphyschem201112596697321416574

- SikongLKongreongBKantachoteDSutthisripokWPhotocatalytic activity and antibacterial behavior of Fe3+-doped TiO2/SnO2 nanoparticlesEnergy Res J201012120125

- HuangZManessPCBlakeDMWolfrumEJSmolinskiSLJacobyWABactericidal mode of titanium dioxide photocatalysisJ Photochem Photobiol A Chem20001302–3163170

- GerrityDRyuHCrittendenJAbbaszadeganMPhotocatalytic inactivation of viruses using titanium dioxide nanoparticles and low-pressure UV lightJ Environ Sci Health A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng200843111261127018642149

- MitorajDJanczykAStrusMVisible light inactivation of bacteria and fungi by modified titanium dioxidePhotochem Photobiol Sci20076664264817549266

- ZhangAPSunYPPhotocatalytic killing effect of TiO2 nanoparticles on Ls-174-t human carcinoma cellsWorld J Gastroenterol200410213191319315457572

- SrinivasanCSomasundaramNBactericidal and detoxification effects of irradiated semiconductor catalyst, TiO2Curr Sci2003851014311438

- DesaiVSKowshikMAntimicrobial activity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthesized by sol-gel techniqueRes J Microbiol20094397103

- Acosta-TorresLSLopez-MarinLMNunez-AnitaREHernandez-PadronGCastanoVMBiocompatible metal-oxide nanoparticles: nanotechnology improvement of conventional prosthetic acrylic resinsJ Nanomater20112011941561

- LiQMahendraSLyonDYAntimicrobial nanomaterials for water disinfection and microbial control: potential applications and implicationsWater Res200842184591460218804836

- TrapalisCTiO2(Fe3+) nanostructured thin films with antibacterial propertiesThin Solid Films20034331–2186190

- ShenJHuYShiMLiNMaHYeMOne step synthesis of graphene oxide–magnetic nanoparticle compositeJ Phys Chem C2010114314981503

- PaekSMYooEHonmaIEnhanced cyclic performance and lithium storage capacity of SnO2/graphene nanoporous electrodes with three-dimensionally delaminated flexible structureNano Lett200991727519090687

- MengXGengDLiuJLiRSunXControllable synthesis of graphene-based titanium dioxide nanocomposites by atomic layer depositionNanotechnology2011221616560221393829

- ZhangHXuPDuGA facile one-step synthesis of TiO2/graphene composites for photodegradation of methyl orangeNano Res201143274283

- LambertTNChavezCAHernandez-SanchezBSynthesis and characterization of titania-graphene nanocompositesJ Phys Chem C2009113461981219823

- GuoJZhuSChenZSonochemical synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles on graphene for use as photocatalystUltrason Sonochem20111851082109021482166

- WilliamsGSegerBKamatPVTiO2-graphene nanocomposites UV-assisted photocatalytic reduction of graphene oxideACS Nano2008271487149119206319

- ZhangHLvXLiYWangYLiJP25-graphene composite as a high performance photocatalystACS Nano20104138038620041631

- ByrappaKYoshimuraMHandbook of Hydrothermal Technology: A Technology for Crystal Growth and Materials ProcessingNew YorkWilliam Andrew Publishing2001

- SuCTsengCMChenLFYouBHHsuBCChenSSSol- hydrothermal preparation and photocatalysis of titanium dioxideThin Solid Films20064981–2259265

- DemazeauGSolvothermal processes: a route to the stabilization of new materialsJ Mater Chem1999911518

- Kolen’koYVMaximovVDGarshevAVMeskinPEOleynikovNNChuragulovBRHydrothermal synthesis of nanocrystalline and mesoporous titania from aqueous complex titanyl oxalate acid solutionsChem Phys Lett20043884–6411415

- ShenJYanBShiMMaHLiNYeMOne step hydrothermal synthesis of TiO2-reduced graphene oxide sheetsJ Mater Chem2011211034153421

- HuangNMLimHNChiaCHYarmoMAMuhamadMRSimple room-temperature preparation of high-yield large-area graphene oxideInternational Journal of Nanomedicine201163443344822267928

- LimHNHuangNMLimSSHarrisonIChiaCHFabrication and characterization of graphene hydrogel via hydrothermal approach as a scaffold for preliminary study of cell growthInt J Nanomedicine2011611817182321931479

- BondAMMarkenFMechanistic aspects of the electron and ion transport processes across the electrode/solid/solvent (electrolyte) interface of microcrystalline decamethylferrocene attached mechanically to a graphite electrodeJ Electroanal Chem19943721–2125135

- ParedesJIVillar-RodilSMartinez-AlonsoATasconJMGraphene oxide dispersions in organic solventsLangmuir20082419105601056418759411

- McAllisterMJLiJLAdamsonDHSingle sheet functionalized graphene by oxidation and thermal expansion of graphiteChem Mater2007191843964404

- ZhangLLiXHuangYMaYFWanXJChenYSControlled synthesis of few-layered graphene sheets on a large scale using chemical exfoliationCarbon201048823672371

- MuruganAVMuraliganthTManthiramARapid, facile microwave-solvothermal synthesis of graphene nanosheets and their poly-aniline nanocomposites for energy storageChem Mater2009212150045006

- XuZWHuangYDMinCYChenLEffect of γ-ray radiation on the polyacrylonitrile based carbon fibersRadiat Phys Chem Oxf Engl 19932010798839843

- WangGHydrothermal synthesis and photocatalytic activity of nanocrystalline TiO2 powders in ethanol-water mixed solutionsJ Mol Catal A Chem20072741–2185191

- XuYJZhuangYFuXNew insight for enhanced photocatalytic activity of TiO2 by doping carbon nanotubes: a case study on degradation of benzene and methyl orangeJ Phys Chem C2010114626692676

- ShenJShiMYanBMaHLiNYeMIonic liquid-assisted one-step hydrothermal synthesis of TiO2-reduced graphene oxide compositesNano Res201148795806