?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

As nanomaterials are now widely utilized in a wide range of fields for both medical and industrial applications, concerns over their potential toxicity to human health and the environment have increased. To evaluate the toxicity of long-term exposure to carbon nanofibers (CNFs) in an in vivo system, we selected Drosophila melanogaster as a model organism. Oral administration of CNFs at a concentration of 1,000 μg/mL had adverse effects on fly physiology. Long-term administration of a high dose of CNFs (1,000 μg/mL) reduced larval viability based on the pupa:egg ratio, adult fly lifespan, reproductive activity, climbing activity, and survival rate in response to starvation stress. However, CNFs at a low concentration (100 μg/mL) did not show any significant deleterious effect on developmental rate or fecundity. Furthermore, long-term administration of a low dose of CNFs (100 μg/mL) increased lifespan and climbing ability, coincident with mild reactive oxygen species generation and stimulation of the antioxidant system. Taken together, our data suggest that a high dose of CNFs has obvious physiological toxicity, whereas low-dose chronic exposure to CNFs can actually have beneficial effects via stimulation of the antioxidant defense system.

Introduction

Nanomaterials are defined as materials with size dimensions on the nanoscale. Nanomaterials are widely utilized in a wide variety of fields for both medical and industrial applications, such as fillers, catalysts, semiconductors, cosmetics, microelectronics, tissue engineering, drug delivery, gene therapy, and biosensor technology.Citation1–Citation4 Accordingly, concerns over their potential toxicity to human health and the environment have increased. The small size of nanomaterials grants unique physicochemical properties such as high conductivity, strong optical scattering properties, strong absorbance, and ease of functionalization, but also induction of toxicological aspects.Citation5

Among various nanomaterials, fibrous nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes and carbon nanofibers (CNFs) have unique electronic and mechanical properties due to their tubular structure. Concerns over the toxicity of fibrous nanomaterials have been raised due to their structural similarity with asbestos, although their chemical composition and physic-mechanical properties are reported to be very different from asbestos.Citation6 In addition, CNFs possess distinct properties from carbon nanotubes.Citation7 Structurally, single-walled carbon nanotubes are composed of a rolled-up cylindrical sheet of graphene, whereas CNFs are formed from stacked graphene nanocones.Citation8 CNFs are strong and flexible filaments ranging from 70 to 200 nm in diameter and 10–100 μm in length, and they are usually used in advanced composite materials to improve strength, stiffness, durability, electrical conductivity, and heat resistance.Citation9 CNFs are cost-effective compared to carbon nanotubes, and thus their commercial applicability has grown exponentially. Despite the widespread use of CNFs, toxicological studies on fibrous nanomaterials have mainly focused on carbon nanotubes. Furthermore, among the few studies that have evaluated CNF toxicity, only in vitro-cultured cell models have been used.Citation7,Citation10,Citation11

Although nanomaterial-mediated toxicity has been largely attributed to the generation of free radicals, the exact molecular mechanism underlying reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation by nanoparticles remains unclear.Citation12–Citation14 Flies exposed to silver nanoparticles are known to show depleted levels of glutathione (GSH) as well as increased antioxidant enzyme SOD and CAT activities.Citation15 In addition, coadministration of silver nanoparticles with an antioxidant such as vitamin C or vitamin C palmitate has been shown to significantly increase survivorship and development in flies.Citation16 These reports suggest that the primary mechanism behind the toxicity of silver nanoparticles is induction of oxidative stress. Furthermore, titanium dioxide nanofibers are reported to induce oxidative stress-mediated cytotoxicity and apoptosis in HeLa cells,Citation17 and CNFs are known to increase intracellular ROS production in Schwann cells.Citation10

Although nanomaterial toxicity has been investigated, there have been only a few reports on the long-term effects of exposure to carbon nanomaterials in an in vivo model system. Drosophila melanogaster has attracted attention as a model system for evaluating the toxicities of artificial materials.Citation18 Drosophila has many beneficial aspects, including ease of handling, various genetic tools, and a short lifespan.Citation19 Recent studies have demonstrated nanomaterial toxicity in a D. melanogaster model system. Specifically, long-term exposure of D. melanogaster to silver nanoparticles during development has been shown to increase genetic instability related to somatic recombination as well as perturb copper homeostasis, resulting in impaired body pigmentation.Citation20,Citation21 Short-term exposure of Drosophila larvae to silver nanoparticles is associated with induction of oxidative stress and apoptosis.Citation15 In addition, long-term exposure to gold nanoparticles (12 μg/g) was reported to reduce lifespan and fertility in flies,Citation22 depending on nanoparticle concentration rather than size.Citation23 On the other hand, several reports have suggested that nanomaterials actually have no adverse effects in Drosophila. Functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes with a hydroxyl group, organically modified silica nanoparticles, and gallium phosphide nanowires have all been reported as having no significant adverse effects on Drosophila development or adult lifespan.Citation24–Citation26 In addition, gellan gum–polyethylenimine nanocomposites show no significant effects on Drosophila survival,Citation27 and long-term exposure to insulin-small lipid nanoparticles developed for insulin delivery is reported to be nontoxic.Citation28

In the current study, we evaluated the physiological effects of long-term exposure to CNFs using D. melanogaster. CNFs at a concentration of 1,000 μg/mL showed adverse effects on development rate and lifespan, whereas 100 μg/mL of CNF supplementation showed hormetic beneficial effects on Drosophila physiology.

Materials and methods

Scanning electron microscopy

CNFs (PR-24-XT-OX, low-crystalline, 100 nm diameter, 45 m2/g surface area) were obtained from Pyrograf Products, Inc. (Cedarville, OH, USA). CNF powder was attached on an aluminum mount with double-stick carbon tape and sputter-coated with platinum. Images were collected on a Hitachi S4300 field emission scanning electron microscope.

Drosophila stocks and husbandry

Canton-S wild-type flies were cultured and reared at 25°C and 65% humidity on a 12:12-hour light:dark cycle. Normal cornmeal–sugar–yeast (CSY) media (5.2% cornmeal, 11% sugar, 2.6% instant yeast, 0.5% propionic acid, 0.2% methyl-4-hydroxybenzoate [Sigma-Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA], and 0.8% agar) were used to culture and rear the parent flies.

Supplementation of CNFs

Following previous reports on nanomaterial supplementation to flies,Citation15,Citation25,Citation29–Citation31 CNFs were suspended in ethanol (0.5, 5% wt), and stock CNF solutions were added to normal CSY or sucrose–yeast (SY) fly media (10% sugar, 10% instant yeast, 0.2% methyl-4-hydroxybenzoate, 0.5% propionic acid, and 0.8% agar) to make food with a final CNF concentration of 100 or 1,000 μg/mL (0.01 or 0.1% wt). Parent flies reared on normal CSY media were transferred to CNF-containing CSY food in order to lay eggs for 24 hours. Newly eclosed F1-generation adults developed on CNF-containing CSY food were collected over 24 hours and used in all experiments after pre-feeding with a CNF-containing SY diet.

Measurement of viability in developmental stages

For larval viability, parent flies reared on normal CSY media were transferred to CNF-containing CSY food in order to lay eggs for 16 hours. After egg deposition, ten eggs were collected and transferred to fresh vials containing CSY diet with or without CNFs. The number of pupae was recorded at the time point when additional pupae no longer emerged.

For pupal viability, the vials used for measurement of larval viability were maintained at 25°C. The number of newly eclosed adult flies was recorded at the time point when all flies had hatched. Thirty replicates were established for each CNF dose.

Crystal cell assay

Parent flies reared on normal CSY media were transferred to CNF-containing CSY food in order to lay eggs for 24 hours. At the third instar stage (L3), larvae were collected and incubated at 70°C for 10 minutes to induce rupture of crystal cells, followed by release of enzymes leading to melanin production. Melanized dots were counted in abdominal segments A6, A7, and A8.

Lifespan assays

Newly eclosed Canton-S adult flies developed on CNF-containing CSY food or standard CSY food were collected over 48 hours and randomly assigned to 500 cm3 demography cages at a final density of 100 female and 100 male flies per cage. The vials containing fresh SY food with or without CNF were affixed to separate cages and changed every 2 days, after which dead flies were removed and recorded. Three replicate cages were established for each CNF dose. Experiments were conducted twice. Age-specific mortality rate (μt) was estimated by the Gompertz equation:

Measurement of feeding rate

Newly eclosed adult flies developed on CNF-containing CSY food were pretreated with CNFs for 7 days. After starvation for 6 hours, ten single-sex flies were transferred into a new vial containing the same diet and bromophenol blue dye (0.05% wt/vol) for 12 hours. The anesthetized flies were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and homogenized in 0.5 mL of distilled water. The absorbance of homogenate was measured at 595 nm using a spectrophotometer. Ten replicate vials were tested per treatment.

Measurement of fecundity

Within the first 24 hours of eclosion, adult flies developed on CNF-containing CSY food were collected, and each vial was set up at a density of two males and one female. Flies were transferred into new vials containing fresh SY food with or without CNF daily, and the number of eggs laid by each female was evaluated for 10 days. Fifteen replicate vials were tested per treatment.

Measurement of physical activity

To measure physical activity, adult flies developed on CNF-containing CSY food were fed SY diets containing the same concentration of CNFs for 1 or 3 week(s) prior to performing a vertical climbing assay. Flies were collected under brief CO2 anesthesia (1–2 minutes) and allowed to recover for at least 18 hours. Ten single-sex flies were loaded into the apparatus for vertical climbing assay and tapped on a tabletop three times in rapid succession to initiate negative geotaxis responses. Positions of flies in the tubes were captured by digital images taken 4 seconds after initiating the behavior. The flies were assessed in consecutive trials separated by 1 minute of rest. Five replicates for each treatment and four trials were used in all experiments.

Stress resistance test

For starvation stress, flies developed on CNF-containing CSY food were pretreated with the same concentration of CNFs for 7 days, after which flies were kept in vials (ten single-sex flies per vial) containing 0.8% agar and transferred into fresh vials containing agar every 6 hours. Dead flies were scored after each transfer. Fifteen replicates were established.

Measurement of intracellular GSH/GSSG level

Total GSH and GSH disulfide (GSSG) levels were measured in a recycling assay using a commercially available GSH/GSSG kit (GT40; Oxford Biomedical, Oxford, MI, USA). Briefly, 20 male flies were homogenized in ice-cold 5% metaphosphoric acid solution, and supernatants were used for measurement of total GSH and GSSG levels based on extent of 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoic acid formation monitored at 415 nm for 10 minutes. The amounts of GSH and GSSG were calculated from a GSSG standard curve (μM), as detailed in the manufacturer’s instructions.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

For real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) in larvae, eggs were developed on CNF-containing food, and total RNAs from 13 wandering third-instar larvae were extracted using RNAiso (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan). For real-time qPCR in adult flies, total RNAs were extracted using RNAiso from 15 male flies after CNF feeding for 7 days. Total RNAs (2 μg) were reverse-transcribed using MMLV reverse transcriptase (Promega Corporation, Fitchburg, WI, USA). qPCR was performed using the Prism7500 Sequence Detection System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and SYBR Green (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. All experiments were repeated at least three times, and the data are presented as the mean ± the standard error of the mean. The oligonucleotide sequences for defensin,Citation33 superoxide dismutase (SOD)1,Citation34 SOD2,Citation35 and catalase (Cat)Citation34 were previously reported. Ribosomal protein 49 (Rp49)Citation36 was used as an internal control.

Statistical analysis

Statistical log-rank tests for the demographic data were carried out using survival models in the JMP statistical package (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). For the analysis of variance and t-test, we used Excel in Microsoft Office 2010.

Results

Effects of CNFs on Drosophila viability in developmental stage

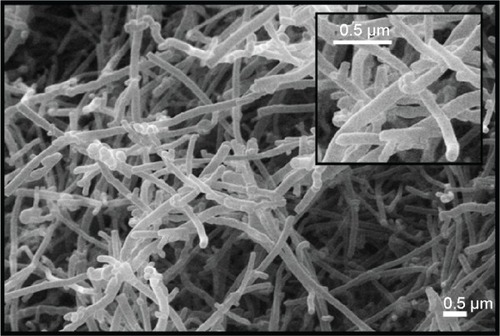

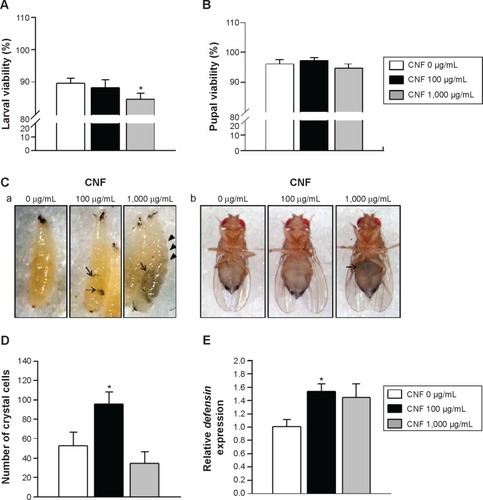

To characterize CNFs used in this study, we measured the diameter and length of CNFs using field emission scanning electron microscopy. CNF diameters ranged from 150 to 200 nm, and length of CNFs was approximately 2–15 μm (). To investigate CNF toxicity, we first measured the viability of larvae supplemented with CNF suspension at a concentration of 100 or 1,000 μg/mL. Larval viability, defined as the number of pupae formed per egg, significantly decreased upon feeding with 1,000 μg/mL of CNF diet (5.58% decrease, P<0.05), whereas viabilities of 100 μg/mL of CNF diet cohorts were unchanged (). Pupal viability, defined as the number of adults eclosed per pupae formed, was unchanged at both CNF concentrations (). In addition, developmental time was slightly delayed with 1,000 μg/mL of CNF diet (data not shown). The external appearance of flies reared on CNF food was not significantly altered compared to that of control, except for dark masses considered to be CNF aggregation in the body cavities of larvae and adults ( [arrows]). Furthermore, black spots appeared in segments of larvae reared on 1,000 μg/mL of CNF diet, suggesting that ingested CNFs were absorbed by flies and induced a biological response ( [arrow heads]). We next analyzed the immune response of larvae exposed to CNFs, as black spots shown in larval segments were considered as immune granules. For this, we observed the number of crystal cells, which are a type of blood cell produced upon immune challenge in flies that can be visual-ized upon heat exposure of larvae.Citation25 The number of crystal cells significantly increased upon ingestion of 100 μg/mL of CNFs (). Furthermore, expression of defensin, an antimicrobial peptide related to innate immunity of flies, increased upon ingestion of 100 μg/mL of CNFs (). This result indicates that CNFs affected the viability of Drosophila throughout its developmental stages and stimulated the immune response.

Figure 1 Scanning electron microscopic images of carbon nanofiber (CNF).

Notes: The diameter of CNFs is approximately 150–200 nm, and the length of CNFs is approximately 3–15 μm. The scale bars correspond to 0.5 μm.

Figure 2 Effects of CNFs on larval and pupal viability in Drosophila.

Notes: (A) Larval viability was determined based on the pupa:egg ratio. Oral administration of CNFs at a dose of 100 μg/mL did not significantly affect larval viability (black bar), whereas 1,000 μg/mL of CNF administration significantly reduced larval viability (gray bar) compared to the control (white bar). *P<0.05. (B) Pupal viability was determined based on the eclosed adult:pupa ratio. CNF administration at both 100 and 1,000 μg/mL did not significantly alter pupal viability. (C) Microscopic images of larvae (a) and adult flies (b) reared on CNF-containing food. Larvae and adult flies reared on CNF-containing food showed dark masses on their body cavities (arrows). Arrowheads indicate melanotic spots in segments of larvae. (D) The number of crystal cells in larvae reared on CNF-containing food and visualized by heat shock-induced melanization increased upon administration of 100 μg/mL of CNFs. *P<0.05. (E) The mRNA levels of defensin were analyzed via real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Expression level of defensin was increased upon 100 μg/mL of CNF administration. *P<0.05.

Abbreviation: CNF, carbon nanofiber.

Effects of CNFs on Drosophila lifespan

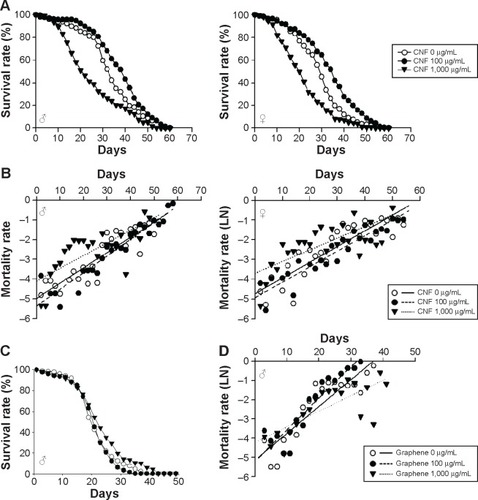

We next investigated the effects of long-term exposure to CNFs on the adult fly lifespan. Newly eclosed flies were fed the same concentrations of CNF diet during development, and the number of survivors was counted every 2 days until all flies died. Survival analyses were performed based on the number of deaths recorded and evaluated by the Mantel–Cox log-rank test. The lifespan of flies supplemented with 1,000 μg/mL of CNFs significantly decreased in both sexes (). The mean lifespan of control male flies was 33.6±0.78 days, whereas that of 1,000 μg/mL of CNF-supplemented male flies was 25.04±0.89 days (25.47% decrease compared to control, log-rank test, χ2=37.04, P<0.0001). For female flies, the mean lifespan of control was 29.36±0.77 days, whereas that of 1,000 μg/mL of CNF-supplemented flies was 21.86±0.74 days (25.56% decrease compared to control, log-rank test, χ2=35.39, P<0.0001). Consistent with the survival data, the age-specific mortality rate of flies supplemented with 1,000 μg/mL of CNFs significantly increased in both sexes (). However, the lifespan of 100 μg/mL of CNF-supplemented flies increased in both sexes. The mean lifespan of 100 μg/mL of CNF-supplemented male flies was 38.01±0.79 days (13.11% increase compared to control, log-rank test, χ2=14.76, P<0.0001), whereas the mean lifespan of 100 μg/mL of CNF-supplemented female flies was 33.96±0.78 days (15.67% increase compared to control, log-rank test, χ2=22.22, P<0.0001). The increased lifespan of 100 μg/mL of CNF-supplemented flies can be attributed to the hormetic effect of mild stress induced by exposure to a low-dose CNF diet (see “Discussion”). To confirm whether or not these beneficial or adverse effects could be attributed specifically to CNFs, we analyzed the survival rate of flies administered graphene, a flat monolayer form of carbon nanomaterials. At the same dose of CNFs, graphene did not significantly decrease the survival or mortality rate of flies (). These results indicate that a high dose of CNF had toxic effects on fly survival. Further, this toxicity was CNF-specific and not a general characteristic of nanomaterials since graphene did not show any toxicity.

Figure 3 Effects of CNF oral administration on adult viability in Drosophila melanogaster.

Notes: (A) Chronic administration of CNFs at a dose of 1,000 μg/mL reduced survival time of Drosophila (lines with black triangles; male, P<0.0001; female, P<0.0001). However, the lifespan of flies administered 100 μg/mL of CNFs significantly increased (lines with black circles; male, P<0.0001; female, P<0.0001). (B) Mortality curves showing age-specific mortality rates of flies administered CNFs. The natural log of the mortality rate was plotted using the Gompertz mortality model. Age-specific mortality rates of both male and female flies administered 1,000 μg/mL of CNFs significantly increased, whereas those of flies administered 100 μg/mL of CNFs slightly decreased. (C) Administration of graphene at the same dose as CNF did not decrease the survival rate of Drosophila (male flies, 100 μg/mL, P<0.1617; 1,000 μg/mL, 9.52% increase of mean lifespan, P<0.0001). (D) Age-specific mortality rate of flies exposed to graphene did not increase at early life stages.

Abbreviation: CNF, carbon nanofiber.

Effects of CNFs on Drosophila reproduction, feeding, and locomotion performance

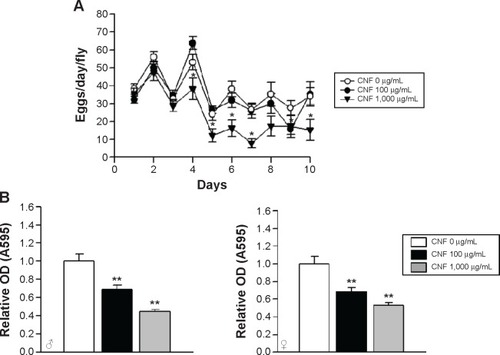

To further analyze the effects of CNFs on the physiology of Drosophila, we investigated the effects of CNFs on fecundity of flies. The fecundity of flies supplemented with 1,000 μg/mL of CNFs significantly decreased, whereas that of flies supplemented with 100 μg/mL of CNFs was unchanged (). Furthermore, we analyzed food intake by CNF-supplemented flies. The amount of food intake by flies reared on CNF-containing food significantly decreased in a dose-dependent manner in both sexes. The amount of food ingested by flies reared on 100 μg/mL of CNFs decreased by approximately 30% compared to the control, whereas that of 1,000 μg/mL of CNF-supplemented flies was only 40%–50% that of the control ().

Figure 4 Effects of CNF ingestion on reproduction and feeding in Drosophila melanogaster.

Notes: (A) Reproductive activity of flies was determined based on the number of eggs obtained from a female fly reared on CNF-containing food. Reproductive activity of flies administered 1,000 μg/mL of CNFs significantly decreased from 4 days after eclosion (line with black triangles). Administration of 100 μg/mL of CNFs did not affect reproductive activity of flies (line with black circles). (B) Food intake by flies was assessed by measuring the amount of blue dye-containing food after 12 hours. Food intake by flies administered CNFs significantly decreased in a dose-dependent manner. *P<0.05; **P<0.001.

Abbreviations: CNF, carbon nanofiber; OD, optical density.

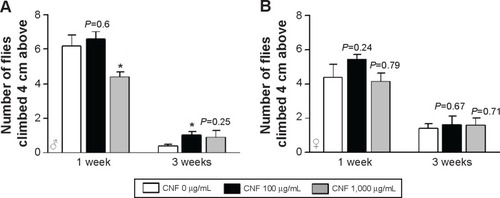

The physical activity of CNF-supplemented flies was also determined by measurement of vertical climbing activity. Supplementation with CNFs did not have any significant effects on physical activity of female flies at both 1 and 3 weeks after eclosion (). In male flies supplemented with 1,000 μg/mL of CNFs, climbing activity significantly decreased at 1 week after eclosion, whereas climbing activity upon 100 μg/mL of CNF supplementation actually increased at 3 weeks after eclosion (). The activity data for males were shown to be consistent with the lifespan data showing an adverse effect of 1,000 mg/mL of CNFs and beneficial effect of 100 μg/mL of CNFs.

Figure 5 Effects of CNF ingestion on physical activity of Drosophila.

Notes: The physical activity of flies was determined by vertical climbing assay. The physical activity of female flies (A) was not significantly affected by CNF administration. However, the physical activity of male flies (B) significantly decreased at 1 week after eclosion upon 1,000 μg/mL of CNF ingestion. Male flies administered 100 μg/mL of CNFs showed enhanced physical activity at 3 weeks after eclosion. *P<0.05.

Abbreviation: CNF, carbon nanofiber.

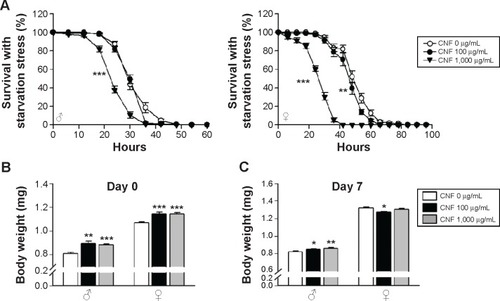

Effects of CNFs on resistance to starvation stress

To investigate the effects of CNFs on susceptibility to stress, we assessed the survival rates of flies reared on CNF-containing food under starvation stress conditions. Male flies reared on standard medium survived for 33.2±0.55 hours under starvation conditions, whereas male flies reared on 1,000 μg/mL of CNFs survived for 25.6±0.51 hours under starvation conditions () (22.9% decrease compared to control, log-rank test, χ2=82.51, P<0.0001). In female flies, the mean lifespan of control flies was 51.52±0.89 hours, whereas that of flies reared on 1,000 μg/mL of CNFs was 28.08±0.7 hours under starvation conditions () (45.5% decrease compared to control, log-rank test, χ2=249.03, P<0.0001). Supplementation with 100 μg/mL of CNFs did not affect lifespan under starvation stress conditions in male flies () (log-rank test, χ2=2.7519, P=0.097), whereas the lifespan of female flies slightly decreased () (11.11% decrease compared to control, log-rank test, χ2=12.33, P<0.001).

Figure 6 Effects of CNF ingestion on resistance to starvation stress and body weight.

Notes: (A) Survival rate of flies administered 1,000 μg/mL of CNFs significantly decreased under starvation conditions (lines with black triangles, P<0.0001), whereas 100 μg/mL of CNFs had a minor effect or none (lines with black circles). (B) Body weight of newly hatched flies is shown. Newly eclosed flies reared on CNF-containing food were heavier than the control. (C) Body weight of 7-day-old flies is shown. Body weight of male flies administered CNFs for 7 days still significantly increased. *P<0.05; **P<0.001; ***P<0.0001.

Abbreviation: CNF, carbon nanofiber.

Resistance to starvation mainly depends on fat content, which is correlated with body weight. The reduced survival under starvation conditions may be attributed to the lower body weight of flies reared on CNFs induced by reduction of feeding rate (). Therefore, the body weight of flies reared on CNFs was measured. Interestingly, body mass of newly eclosed male and female flies developed on CNFs was significantly higher than that of the control, and weight of male flies fed CNFs for an additional 7 days was still heavier than that of the control (). These results suggest that the reduced survival of flies fed CNFs under starvation conditions was not due to reduced food intake.

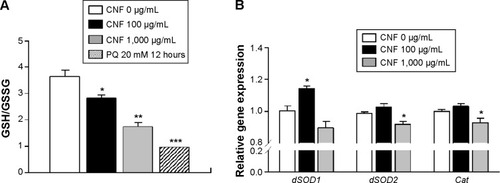

Induction of ROS by CNF supplementation

The toxicity of nanomaterials has been reported to be mainly associated with generation of ROS. In addition, the observed physiological phenomena caused by exposure to CNFs in this study, such as changes in lifespan and development, are known to be related to internal ROS levels. To analyze the internal ROS level in flies reared on CNF-containing diet, total GSH and GSSG levels were measured using 5,5′-dithio-bis-2-nitrobenzoic acid and GSH reductase.Citation37 Total amounts of GSH and GSSG in whole flies supplemented with CNFs were calculated from a GSSG standard curve. Flies treated with 20 mM paraquat for 12 hours were used as a positive control. The GSH/GSSG ratio of control flies was 3.65±0.53, whereas ratios of flies supplemented with 100 and 1,000 μg/mL of CNFs were 2.83±0.19 and 1.75±0.26, respectively (). The reduced GSH/GSSG ratio indicates that oral administration of CNFs generated oxidative stress in Drosophila.

Figure 7 CNF-induced oxidative stress in Drosophila.

Notes: (A) The intracellular reactive oxygen species level was analyzed by measuring the ratio of GSH to GSSG. The GSH/GSSG ratio significantly decreased upon chronic administration of CNFs to Drosophila. Treatment with 20 mM PQ was used as a positive control. (B) The mRNA levels of antioxidant enzymes were analyzed via real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Expression levels of dSOD1, dSOD2, and catalase increased upon 100 μg/mL of CNF administration but decreased upon 1,000 μg/mL of CNF administration. *P<0.05; **P<0.001; ***P<0.0001.

Abbreviations: CNF, carbon nanofiber; GSH, glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; PQ, paraquat.

Under oxidative stress conditions, the antioxidant and detoxification systems of organisms are activated for protection. To investigate the effects of CNF administration on expression of antioxidant enzymes, mRNA levels of SOD and Cat were analyzed using real-time qPCR. Interestingly, transcription levels of cytosolic CuZnSOD (SOD1) increased in whole flies administered 100 μg/mL of CNFs, whereas expression levels of mitochondrial MnSOD (SOD2) and Cat decreased upon 1,000 μg/mL of CNF supplementation (). These results suggest that a high dose of CNFs (1,000 μg/mL) disturbed the antioxidant system of flies, whereas a low dose of CNFs (100 μg/mL) actually stimulated the antioxidant system along with mild generation of ROS.

Discussion

Increased attention toward use of nanomaterials by engineers and biomedical scientists has raised concerns over their toxicity in human health and the environment. In the current study, we analyzed the toxicity of chronic exposure to CNFs using D. melanogaster as an in vivo model system.

Long-term oral administration of CNFs had dose-dependent distinct effects on Drosophila physiology in this study. CNFs showed significant adverse effects on Drosophila at a concentration of 1,000 μg/mL, including reduced larval viability based on the pupa:egg ratio, survival of adult flies, reproductive activity, climbing ability, and survival under starvation stress conditions. Several reports have showed that oral administration of nanomaterials has adverse effects on Drosophila physiology. Especially, silver and gold nanoparticles show toxic effects on Drosophila fecundity and lifespan.Citation21–Citation23,Citation29 On the other hand, other studies reported that nanomaterials lack any significant adverse effects on Drosophila. For example, multi-walled carbon nanotubes at a concentration of 1,000 μg/g were shown to have no significant effect on developmental time or egg viability,Citation31 and single-walled carbon nanotubes at a concentration of 12–24 ppm during larval stage were reported to have no effect on pupal viability.Citation30 Further, carbon nanotubes functionalized with a hydroxyl group were reported to not affect the eclosion rate of flies.Citation24 Assuming a food intake of 1.5 μL per day,Citation38 we speculate that the maximum amount of CNFs consumed by individual flies was 0.15 or 1.5 μg/fly/day in this study, not considering reduction of feeding rate (). Although the amount of CNFs in our fly diet was higher than naturally occurring levels, it is plausible for humans to ingest such abundant amounts of nanomaterials since continuous ingestion of contaminated foods or water is the most common route of nanomaterial ingestion.Citation39 Therefore, our data showing the obvious toxic effects of CNFs on Drosophila physiology provide valuable information for the study of human health.

The adverse effects of chronic exposure to a high dose of CNFs (1,000 μg/mL) are assumed to be the result of direct toxicity. However, we cannot rule out the possibility of indirect toxicological effects caused by reduced food intake. Chronic oral ingestion of CNFs reduced food intake in flies by up to 60%. Reduction of food intake can inhibit reproduction and decrease body weight, subsequently impairing physical activity.Citation40,Citation41 In addition, reduction of stored nutrients increases sensitivity to starvation stress, which ultimately reduces the survival rate.Citation42 Body weight data suggest that reduced food intake did not increase sensitivity to starvation resistance, as body weight did not decrease in CNF-fed flies showing reduced survival under starvation resistance (). Interestingly, newly eclosed male and female flies developed on CNF-containing food were significantly heavier compared to the control. This is possibly due to the delayed development of larvae (data not shown), increasing the feeding period during larval development.

Surprisingly, a low dose of CNFs (100 μg/mL) showed beneficial effects on the physiology of flies. Ingestion of CNFs (100 μg/mL) did not have any significant effect on developmental rate or fecundity. Interestingly, lifespan, climbing activity, and resistance to oxidative stress (data not shown) were improved by long-term oral administration of 100 μg/mL of CNFs. The beneficial effects of 100 μg/mL of CNF supplementation can be explained by reduced food intake. Mild reduction of nutrient intake without malnutrition, known as dietary/calorie restriction, is known to have beneficial effects such as prolonged lifespan and increased resistance to several stresses.Citation43 In addition, independent of reduced food intake, our results can be explained by the hormetic effect, which is a biphasic dose response with a low-dose beneficial effect and high-dose toxic effects.Citation44 Since dietary/calorie restriction is also considered as a mild stress and its beneficial effects are due to the hormetic effect,Citation45 it can be assumed that long-term exposure to a low dose of CNFs functions as a mild stress to activate the defense system in flies against subsequent stresses.

Generation of ROS and subsequent induction of oxidative stress upon exposure to nanomaterials is considered to be the most important toxicity mechanism of nanomaterials.Citation13 The ROS level measured based on the GSH/GSSG ratio increased in flies fed CNFs in a dose-dependent manner, and expression of some antioxidant enzyme(s) increased with a low dose of CNFs (100 μg/mL) but decreased with a high dose of CNFs (1,000 μg/mL). Mild oxidative stress stimulates the defense system, including antioxidant and detoxification enzymes, but this protective response is perturbed and overtaken by inflammation and cytotoxicity at higher levels of oxidative stress.Citation46,Citation47 Thus, a low dose of CNFs may function as a mild stress in flies to activate the defense response, whereas a high dose of CNFs may perturb the defense response, reducing the expression of some antioxidant enzymes.

In summary, long-term oral administration of a high dose of CNFs has obvious toxic effects on fly physiology, possibly due to impairment of feeding performance and antioxidant systems along with enhanced intracellular ROS production. In addition, exposure to a low dose of CNFs has beneficial effects on fly physiology, especially resistance to oxidative stress mediated by enhanced antioxidant defense.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (KRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (number 2013R1A1A2063664).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HarrisonBSAtalaACarbon nanotube applications for tissue engineeringBiomaterials200728234435316934866

- De VolderMFTawfickSHBaughmanRHHartAJCarbon nanotubes: present and future commercial applicationsScience2013339611953553923372006

- MundraRVWuXSauerJDordickJSKaneRSNanotubes in biological applicationsCurr Opin Biotechnol201428253224832071

- RastogiVYadavPBhattacharyaSSCarbon nanotubes: an emerging drug carrier for targeting cancer cellsJ Drug Deliv2014201467081524872894

- JangSJangHLeeYFlexible, transparent single-walled carbon nanotube transistors with graphene electrodesNanotechnology2010214242520120858937

- DonaldsonKPolandCAMurphyFAMacFarlaneMChernovaTSchinwaldAPulmonary toxicity of carbon nanotubes and asbestos – similarities and differencesAdv Drug Deliv Rev201365152078208623899865

- CastranovaVSchultePAZumwaldeRDOccupational nanosafety considerations for carbon nanotubes and carbon nanofibersAcc Chem Res201346364264923210709

- JongKPDGeusJWCarbon nanofibers: catalytic synthesis and applicationsCatal Rev2000424481510

- DarneCTerzettiFCoulaisCIn vitro cytotoxicity and transforming potential of industrial carbon dust (fibers and particles) in syrian hamster embryo (SHE) cellsAnn Occup Hyg201054553254420219837

- JainSWebsterTJSharmaABasuBIntracellular reactive oxidative stress, cell proliferation and apoptosis of Schwann cells on carbon nanofibrous substratesBiomaterials201334214891490123570716

- KisinERMurrayARSargentLGenotoxicity of carbon nanofibers: are they potentially more or less dangerous than carbon nanotubes or asbestos?Toxicol Appl Pharmacol2011252111021310169

- GreenMHowmanESemiconductor quantum dots and free radical induced DNA nickingChem Commun (Camb)2005112112315614393

- NelAXiaTMädlerLLiNToxic potential of materials at the nanolevelScience2006311576162262716456071

- MonteillerCTranLMacNeeWThe pro-inflammatory effects of low-toxicity low-solubility particles, nanoparticles and fine particles, on epithelial cells in vitro: the role of surface areaOccup Environ Med200764960961517409182

- AhamedMPosgaiRGoreyTJNielsenMHussainSMRoweJJSilver nanoparticles induced heat shock protein 70, oxidative stress and apoptosis in Drosophila melanogasterToxicol Appl Pharmacol2010242326326919874832

- PosgaiRCipolla-McCullochCBMurphyKRHussainSMRoweJJNielsenMGDifferential toxicity of silver and titanium dioxide nanoparticles on Drosophila melanogaster development, reproductive effort, and viability: size, coatings and antioxidants matterChemosphere2011851344221733543

- RamkumarKMManjulaCGnanakumarGOxidative stress-mediated cytotoxicity and apoptosis induction by TiO2 nanofibers in HeLa cellsEur J Pharm Biopharm201281232433322446064

- OngCYungLYCaiYBayBHBaegGHDrosophila melanogaster as a model organism to study nanotoxicityNanotoxicology Epub2014722

- LeeHYLeeSHMinKJInsects as a model system for aging studiesEntomological Research2015

- DemirEValesGKayaBCreusAMarcosRGenotoxic analysis of silver nanoparticles in DrosophilaNanotoxicology20115341742421039182

- ArmstrongNRamamoorthyMLyonDJonesKDuttaroyAMechanism of silver nanoparticles action on insect pigmentation reveals intervention of copper homeostasisPLoS One201381e5318623308159

- PompaPPVecchioGGaleoneAIn vivo toxicity assessment of gold nanoparticles in Drosophila melanogasterNano Res201144405413

- VecchioGGaleoneABrunettiVConcentration-dependent, size-independent toxicity of citrate capped AuNPs in Drosophila melanogasterPLoS One201271e2998022238688

- PhilbrookNAWalkerVKAfroozARSalehNBWinnLMInvestigating the effects of functionalized carbon nanotubes on reproduction and development in Drosophila melanogaster and CD-1 miceReprod Toxicol201132444244821963887

- AdolfssonKSchneiderMHammarinGHäckerUPrinzCNIngestion of gallium phosphide nanowires has no adverse effect on Drosophila tissue functionNanotechnology2013242828510123787695

- BarandehFNguyenPLKumarROrganically modified silica nanoparticles are biocompatible and can be targeted to neurons in vivoPLoS One201271e2942422238611

- GoyalRTripathiSKTyagiSGellan gum-PEI nanocomposites as efficient gene delivery agentsJ Biomed Nanotechnol201171383921485792

- FangueiroJFGonzalez-MiraEMartins-LopesPA novel lipid nanocarrier for insulin delivery: production, characterization and toxicity testingPharm Dev Technol201318354554921711084

- PanacekAPrucekRSafarovaDAcute and chronic toxicity effects of silver nanoparticles (NPs) on Drosophila melanogasterEnviron Sci Technol201145114974497921553866

- LeeuwTKReithRMSimonetteRASingle-walled carbon nanotubes in the intact organism: near-IR imaging and biocompatibility studies in DrosophilaNano Lett2007792650265417696559

- LiuXVinsonDAbtDHurtRHRandDMDifferential toxicity of carbon nanomaterials in Drosophila: larval dietary uptake is benign, but adult exposure causes locomotor impairment and mortalityEnviron Sci Technol200943166357636319746737

- MuellerLDNusbaumTJRoseMRThe Gompertz equation as a predictive tool in demographyExp Gerontol19953065535698867525

- SeongKMKimCSSeoSWGenome-wide analysis of low-dose irradiated male Drosophila melanogaster with extended longevityBiogerontology20111229310720617381

- TsudaMOotakaROhkuraCLoss of Trx-2 enhances oxidative stress-dependent phenotypes in DrosophilaFEBS Lett2010584153398340120600005

- ShenLRXiaoFYuanPCurcumin-supplemented diets increase superoxide dismutase activity and mean lifespan in DrosophilaAge (Dordr)20133541133114222653297

- BiteauBHochmuthCEJasperHJNK activity in somatic stem cells causes loss of tissue homeostasis in the aging Drosophila gutCell Stem Cell20083444245518940735

- PalAKHsiehSFKhatriMScreening for oxidative damage by engineered nanomaterials: a comparative evaluation of FRAS and DCFHJ Nanopart Res2014162167

- DeshpandeSACarvalhoGBAmadorAQuantifying Drosophila food intake: comparative analysis of current methodologyNat Methods201411553554024681694

- WangHWangJDengXBiodistribution of carbon single-wall carbon nanotubes in miceJ Nanosci Nanotechnol2004481019102415656196

- BrossTGRoginaBHelfandSLBehavioral, physical, and demographic changes in Drosophila populations through dietary restrictionAging Cell20054630931716300483

- O’BrienDMMinKJLarsenTTatarMUse of stable isotopes to examine how dietary restriction extends Drosophila lifespanCurr Biol2008184R155R15618302914

- MinKJTatarMRestriction of amino acids extends lifespan in Drosophila melanogasterMech Ageing Dev2006127764364616616772

- LeeSHMinKJCaloric restriction and its mimeticsBMB Rep201346418118723615258

- KirkwoodTBShanleyDPCaloric restriction, hormesis and life history plasticityHum Exp Toxicol200019633833910962502

- MartinsIGalluzziLKroemerGHormesis, cell death and agingAging (Albany NY)20113982182821931183

- ChakrabortyPKMustafiSBRahaSPro-survival effects of repetitive low-grade oxidative stress are inhibited by simultaneous exposure to ResveratrolPharmacol Res2008585–628128918812223

- SenPMukherjeeSBhaumikGEnhancement of catalase activity by repetitive low-grade H2O2 exposures protects fibroblasts from subsequent stress-induced apoptosisMutat Res20035291–2879412943922