Abstract

Cervical cancer (CC) is a leading cause of cancer-related death and a major public health issue in sub-Saharan Africa. This heavy burden parallels that of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, which increases the risk of developing CC. Despite the progressive reduction of HIV prevalence in the past decade, the CC incidence and mortality rates in sub-Saharan Africa remain high. The heterogeneity of the distribution of the two diseases in the African continent, together with the different availability of human and material resources, stands in the way of finding an appropriate screening strategy. The lack of high-quality evidence on the prevention of CC for HIV-positive women, which is necessary for the implementation of efficient screening and treatment strategies, results in the absence of a clearly defined program, which is responsible for the low screening uptake and high mortality rates in sub-Saharan Africa. By taking advantage of the HIV-positive women’s frequent access to health facilities, one way to increase the CC screening coverage rates would be by providing integrated HIV and screening services within the same infrastructure. With the increasing availability of cost-effective methods, screening is becoming more and more available to women who have limited access to health care. Moreover, the introduction of point-of-care technologies for human papillomavirus testing and the subsequent implementation of screen-and-treat strategies, by reducing the number of clinical appointments and, in the long term, the loss to follow-up rates, open up new opportunities for all women, regardless of their HIV status. The purpose of this review is to provide an insight into the different screening practices for CC in order to help define one that is adapted to the resources and necessities of HIV-positive women living in middle-to-low income countries.

Introduction

As the prevalence of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and that of cervical premalignant lesions in certain regions reach 20% and 9%, respectively, these two diseases represent two important public health issues in sub-Saharan Africa.Citation1–Citation4 Since the onset of the HIV epidemic in the late 1970s, the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has labeled cervical cancer (CC) as an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining disease.Citation5 The global incidence of CC in sub-Saharan Africa ranges from 43.3/100,000 to 69.8/100,000 women, as opposed to an incidence of 9/100,000 to 12.8/100,000 reported in Europe.Citation6–Citation9

A growing body of evidence supports the fact that human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the main cause for the development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and invasive CC.Citation10 Infection with HIV significantly increases a woman’s risk of developing cervical premalignant lesions and cancer by impairing her natural cell-mediated immune response, and thereby, altering her capacity of properly eliminating HPV.Citation11–Citation13 Furthermore, evidence coming from studies conducted both in industrialized and developing countries has shown that the risk of developing cervical premalignant lesions increases as the CD4 count lowers.Citation14,Citation15 This association could be more relevant in sub-Saharan Africa, where access to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and subsequent retention in care are still real challenges.Citation16,Citation17

The development of health care infrastructure, together with an increased access to HAART, has significantly decreased the worldwide AIDS-related mortality over the past few years.Citation18 In sub-Saharan Africa, in particular, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2015 guidelines have extended the treatment criteria initiation to all patients, regardless of their CD4+ count, in an effort to make more HIV-positive people eligible for therapy.Citation19 This translates into an increased life expectancy for HIV-infected women, which subsequently exposes them to the risk of developing other AIDS-defining cancers. Whereas most AIDS-related diseases are progressively becoming less frequent, CC’s incidence has not substantially decreased with the growing use of antiretroviral therapy.Citation20

In the 2014 guidelines, the WHO has stated the need to fulfill the research gap in the CC screening and follow-up of HIV-positive women living in developing countries.Citation21 As the lack of good quality evidence makes it difficult to define the screening intervals and modalities for HIV-infected patients, the current guidelines for this high-risk group of women are mostly based on expert opinion.Citation21

The aim of the present study is to provide an overview of the current CC screening strategies for HIV-infected women and to discuss the current issues and research gap on the subject to the extent of defining the best possible screening approach for a disease that currently has a large impact on the women’s quality of life and expectancy.

Overview of the current screening strategies and issues

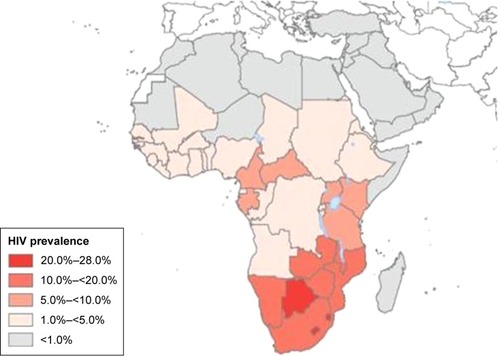

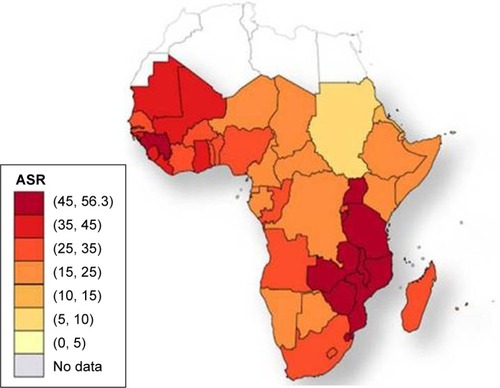

The incidence rates of CC in Africa vary widely by geographical region.Citation6 and show the distribution of the HIV epidemic and the incidence of CC in the different African countries. Despite the growing evidence supporting the association between HIV and HPV infection, the mechanisms resulting in CC are not fully understood, especially for HIV-positive women.Citation22–Citation25 This finding has been confirmed by a study conducted in South Africa and Burkina Faso, which found similar HIV infection rates in the two settings but significantly higher rates of cervical precancerous lesions in South Africa.Citation26 The causes of this heterogeneity remain unclear and may partly be attributed to genetics, lifestyles, environmental factors, and migration patterns. These unregulated trends may explain why the reported CC screening tests’ positivity rates vary widely by country.Citation27,Citation28 The geographical variations in the screening tests’ performance are partly responsible for the difficulty in establishing an efficient screening strategy that is adapted to the resources and capacity of each region.

Figure 1 Global distribution of HIV in Africa in 2007.

Figure 2 Cervical cancer age-standardized incidence rates per 100,000 women in 2008.

Abbreviation: ASR, age-standardized incidence rates per 100,000 women and year.

Despite the accuracy of Pap testing in the detection of cervical lesions among HIV-positive women, the high costs, and the need of human and material resources imply the necessity to consider other alternatives for CC screening in Africa.Citation29 One significant limitation of the current cytology-based screening strategy for the identification of cervical precancerous lesions is represented by the high rate of false negative test results, which have been found to be more frequent in HIV-positive women when compared to the general population.Citation30 Based on this finding, it has been suggested that colposcopy be performed routinely to screen HIV-positive women, which would increase the necessity of paramount human, financial, and material resources.Citation31 In addition, the use of Pap test-based screening in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) has proven to be difficult to provide due to the limited resources for the pathological diagnosis and the significant delay between the primary screening visit and the subsequent treatment, leading to loss to follow-up, and in the long term, disease progression.Citation32

In order to overcome the main obstacles to screening uptake, a reevaluation of the traditional cytology-based screening strategy is advised, with the ultimate aim of extending screening coverage to those women who are, in relation to their HIV status, exposed to a higher risk of developing invasive CC.

Visual inspection methods

The visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) approach for screening prior to treatment of cervical precancerous lesions in the context of a “screen-and-treat” protocol in LMIC is currently recommended by the WHO guidelines.Citation21 This method is often coupled with visual inspection with Lugol’s iodine, which has demonstrated to improve the performance of VIA on HIV-positive women.Citation33

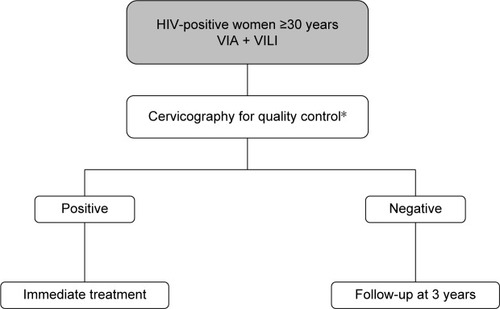

As shown in the decision-making algorithm in , one of the main strengths of visual inspection methods is the prompt availability of the test results, which allows the immediate treatment of screen-positive women. This particular aspect allows health services to contrast the high dropout rates associated with the multiple-visit, cytology-based screening approach, which have proven to reach as much as 80% of women screened in sub-Saharan Africa.Citation34 Several studies have demonstrated that, while being safe and cost-effective, the VIA-based screening approach results in a significant reduction of loss to follow-up among HIV-infected women within a low-resource setting.Citation35–Citation38 Moreover, the overall acceptance rates of HIV-positive women who were offered this screening technique varied from 86% in a study conducted in Mozambique to as much as 96.5% in a study conducted in Nigeria, thus indicating that the majority of women will accept screening for CC with VIA if proactively offered the opportunity to test.Citation39,Citation40 In addition, a multicenter study conducted in sub-Saharan Africa has found that the majority of HIV-infected VIA-positive women were eligible to promptly undergo treatment with cryotherapy, thus further supporting the efficacy of this primary screening method.Citation35 The VIA-based “screen-and-treat” strategy embodied in an HIV service platform has been implemented in Zambia in 2006 and has ever since provided CC screening service to over 100,000 women. Although the program initially targeted only HIV-infected patients, its use has been rapidly extended to all women, regardless of their HIV status, with the aim of improving health education and reducing HIV stigmatization.Citation41

Figure 3 Decision-making algorithm for VIA-based screening.

Abbreviations: VIA, visual inspection with acetic acid; VILI, visual inspection with Lugol’s iodine.

As a screening test to detect CIN grade 2 or worse (CIN2+) among HIV-infected women, VIA has shown a good performance in a large body of studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa.Citation33,Citation37 The different specificity and sensitivity values of VIA across different studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa are reported in . As the lesions occupy a larger area of the cervix, the VIA positivity rates have proven to be higher among HIV-positive women when compared to their HIV-negative counterparts.Citation35 The main drawback of this technique is the subjectivity of the diagnosis, which is influenced by the health worker’s qualitative judgment and experience, and the environmental conditions, in which the examination takes place. In parallel, to what is observed among HIV-negative women, these aspects result in high false positive rates, which limit the technique’s specificity and lead to a risk of overtreatment.Citation42,Citation43 The subjectivity of the diagnosis obtained with visual inspection methods can be minimized by the use of digital cervicography. The use of digital images of the cervix allows users to standardize the visual inspection examination while providing a quality control system.Citation44 Although this technique may seem inappropriate for low-resource settings due to the additional economic, material, and human requirements for its use, several studies have shown its successful implementation in different sub-Saharan African regions.Citation45,Citation46

Table 1 Sensitivity and specificity values of VIA among HIV-positive women across different studies

While the VIA result interpretation, depending mainly on the examiner’s judgment, leads mainly to false positive diagnoses, it may also be responsible for a certain number of false negatives. A recent cost-effectiveness analysis comparing different CC screening methods has demonstrated that, although VIA is the most cost-effective option when compared to cytology and HPV testing, its lower sensitivity when compared to other screening techniques translates into a significantly increased number of missed diagnoses.Citation47 The high rates of false negative diagnoses represent one of the main challenges to the use of this technique for primary screening, as they impose the need of multiple-day, long-distance visits, which are responsible for loss to follow-up. As same day treatment with procedures such as cryotherapy or thermocoagulation has proven to be feasible and well-accepted by patients, one way to reduce loss to follow-up would be to treat all women whose diagnosis is suspicious for a cervical premalignant lesion, although at the cost of increasing the risk of overtreatment.Citation37,Citation48

Despite the technological progress that allows the continuous optimization of this screening method, several studies have found that, in addition to user-dependent factors, there are also patient-related factors, such as age and the presence of vaginal infections, which can influence the capacity to read the VIA results on HIV-positive patients, thus leading to possible test result misinterpretation.Citation49

The limited reliability of visual inspection methods, together with the reluctance expressed by some women to undergo a screening service that involves a pelvic examination, have given way to the introduction of alternative methods, all while taking into account the main human and institutional barriers that keep the current screening coverage rates in sub-Saharan Africa low.

HPV testing

HPV testing has proven to be significantly more sensitive in identifying cervical precancerous lesions when compared with cytology, although at the cost of a lower specificity.Citation29,Citation50 The different sensitivity and specificity values of HPV testing obtained from studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa are reported in . A randomized trial conducted in South Africa has shown that, among 100 screened women, the HPV-based screen-and-treat approach can prevent 12 cases of CIN2+ among HIV-infected women and 3 cases of CIN2+ among HIV-negative patients, whereas VIA can prevent only 7 and 1 case of CIN2+ among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women, respectively.Citation51

Table 2 Sensitivity and specificity of HPV testing among HIV-positive women across different studies

The availability of point-of-care technologies for the detection of HPV, which require limited infrastructure and provide test results within 1 hour, potentially allow the implementation of a same day screen-and-treat approach.Citation52 One of these is GeneXpert (GeneXpert®; Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) which, when used for HPV sample analysis, has shown a higher positive predictive value and sensitivity in the detection of CIN2+ among HIV-positive women when compared to their HIV-negative counterparts.Citation50 Similar results have been observed when using the Hybrid Capture 2 DNA assay (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA).Citation53

Due to the high prevalence of HPV infection among HIV-infected women, the HPV test’s specificity remains limited.Citation52,Citation54 The results from a study conducted in Kenya suggest that decreased HPV specificity is independently associated with age <40 years.Citation29 This finding is consistent with the progressive decrease of HPV infection starting at the age 30 years, whereas the peak incidence of CIN occurs about 10 years later.Citation55,Citation56 For this reason, similar age restrictions to those applied in the USA for HPV screening, which is currently limited to women aged 30 years and older, should apply to HIV-positive women.Citation57

One way to increase the HPV test’s specificity and to potentiate its effectiveness is by combining HPV testing with triage methods. One study conducted in Kenya has demonstrated that the already high sensitivity of HPV testing in HIV-positive women can be further increased by pairing it up with a triage test, such as VIA or cytology.Citation29 The prevalence of specific high-risk HPV types such as HPV-52, HPV-58, HPV-35, and HPV-16 in HIV-positive women is itself a predictor for cervical disease that can be assessed through genotyping.Citation58 Other studies have evaluated the use of alternative triage methods for HPV-positive women. One of these is the identification of E6 protein because real-time nucleic acid sequence-based amplification has proven to allow type-specific detection of E6 mRNA from high-risk HPV types.Citation50,Citation59 Another triage method is the use of methylation markers of host cell genes involved in cervical carcinogenesis, such as CADM1, MAL, and MIR124-2 loci. It has been demonstrated that the combined use of these methylation markers for HIV-infected HPV-positive women is comparable to that of cytology and superior to HPV16/18 genotyping and VIA for the detection of CIN.Citation60

Another study has found that the molecular expression of the insulin-like growth factor II mRNA binding protein 3 (IMP3) and of p16 are significantly higher among HIV-infected women with squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (SIL).Citation61 Moreover, the expression of IMP3 among HIV-positive women is more sensitive than p16 in identifying patients at risk for progression and recurrence of high-grade SIL (HSIL).Citation61 Although this strategy was evaluated solely on clinician-collected cervical samples, it represents another step toward the adoption of molecular tests as a complementary tool for CC screening.

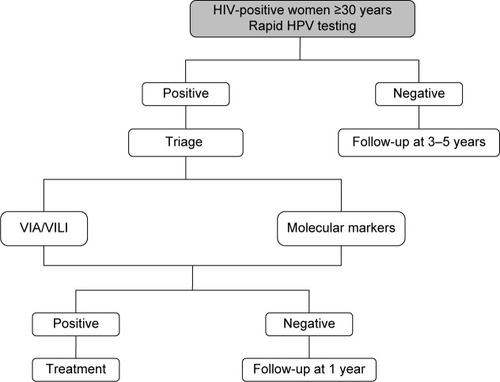

The advantage of HPV genotyping, OncoE6, methylation, and other molecular markers is that they can be assessed in the same cervical sample that is used for primary screening, thus avoiding the need of multiple visits. This aspect makes the molecular screening strategy particularly promising in LMIC, where it could circumvent some of the main practical barriers to CC screening attendance, such as lack of time and unwillingness to undergo multiple clinical visits that entail one or more pelvic examinations.Citation60,Citation62 The decision-making algorithm for HPV-based screening is shown in .

Figure 4 Decision-making algorithm for HPV-based screening.

Another advantage to HPV testing is the possibility of performing self-sampling. The availability of self-screening represents an additional strategy to improve screening coverage in LMIC, where the limited infrastructure and health personnel reduce the effectiveness of the call-recall cytology-based programs.Citation63 The equality of self-collected and clinician-collected HPV samples has been demonstrated by a recent meta-analysis, which found that the two collection methods had similar sensitivity and specificity for the detection of CIN2+ when polymerase chain reaction-based tests are used.Citation64 Furthermore, the results from a recent study conducted in South Africa support the equality of the two methods among HIV-infected women.Citation65

By overcoming some of the main institutional barriers to CC screening, such as limited access to health services, the time-consuming aspect of a multiple-visit approach and the discomfort that can derive from a pelvic examination, the HPV self-sampling approach represents a mean to potentially increase CC screening participation. A recent randomized trial conducted in the USA has demonstrated that offering HPV self-sampling and subsequent results counseling within the same day increases the HIV-positive women’s perception of their CC risk.Citation66 Another study conducted in Uganda has found that self-sampling was well accepted by HIV-infected women, achieving screening attendance rates of >90%.Citation67 The overall advantages and disadvantages associated to the different screening techniques are reported in .

Table 3 Advantages and disadvantages of different CC screening options

Screening uptake

Compared to industrialized countries, where CC screening covers >60% of the target population, screening in developing countries covers <20% of women.Citation68 A recent review has estimated that the screening coverage rates in sub-Saharan Africa range from 2% to 20.2% in urban areas and from 0.4% to 14% in rural areas.Citation69 More specifically South Africa, which accounts for the highest burden of HIV in the world, has a CC screening uptake that was estimated to be 54% in 2013, with local variations that went from a minimum of 32% to a maximum of 75%.Citation65,Citation70

The main intrapersonal obstacles that keep HIV-positive women from undergoing screening include an expected feeling of pain, discomfort, and anxiety that derive from the initial pelvic examination and the subsequent colposcopy in case of a positive screening test.Citation71 In addition, older age and a perceived low risk of developing CC have also proven to be obstacles to screening participation.Citation68,Citation72 Institutional barriers, defined by a limited access to transportation and health care facilities, an extensive waiting time, and systemic issues related to scheduling multiple gynecological appointments, also stand in the way of women attending CC screening.Citation73 There are also socioeconomic factors, such as the cost of the screening service and of the transportation to the health facilities, which may be necessary multiple times depending on the primary test results and the type of strategy that is adopted that can have a negative impact on screening participation.Citation68

Most of the aforementioned institutional and intrapersonal barriers to adequate screening attendance apply to HIV-infected women as much as to their HIV-negative counterparts. The main advantage in favor of HIV-infected women is the fact that their more frequent health facility attendance can be viewed as an opportunity to provide health education, screening, and treatment of cervical precancerous and cancerous lesions within the same facility and, possibly, the same day. According to health care providers, the integration of CC screening in this context would allow to break down the main intrapersonal and institutional barriers that withhold this high-risk group of women from undergoing screening.Citation74

Several studies have proven that information is a key component to increasing screening uptake among women in LMIC.Citation71,Citation74,Citation75 While a study conducted in Ethiopia has found that women are 4 times more likely to undergo CC screening if they have previously been diagnosed with a sexually transmitted disease, another study in Uganda has shown that having multiple medical appointments for HIV and screening-related services can generate a considerable amount of stress and confusion, thus discouraging screening participation.Citation71,Citation72 In addition, not knowing how a screening procedure is performed is responsible for speculations and misconceptions on the CC prevention pathway.Citation71

A recent study conducted on HIV-infected women has shown that, despite the increase in screening participation up to 95% with the use of HPV self-sampling, women were more likely to be lost at the subsequent follow-up visits if they had severe immunosuppression, higher viral loads, and a history of substance abuse.Citation66 A solid health education delivered through HIV services represents the fundamental basis for increasing self-awareness and, subsequently, screening attendance. One study conducted in Western Kenya has found that, while self-reported HIV was associated to increased CC screening attendance, not all women who acknowledged living with HIV underwent screening, thus highlighting the importance of education in this high-risk group of women.Citation76 Growing evidence shows the importance of informing not only the women, but also their male partners, as their support can significantly influence the women’s decision to undergo screening.Citation74,Citation75 One way to ensure the correct transmission of information and to retain patients in health care is by building strong provider–patient relationships, especially for patients with multiple medical and social needs.Citation73

By integrating HIV health care and CC screening services, another one of the main obstacles that can be overcome is the women’s reluctance to attend screening due to the distance to the health care facilities. One study has shown that women having received a pelvic examination for CC screening at a place other than their usual health facility for HIV care were more likely to not undergo screening in the future.Citation77 With the progressive implementation of screen-and-treat strategies, this systemic issue is further tackled by providing HIV care, CC screening, and treatment possibly all within the same day.Citation71

Screening timing, intervals, and follow-up

For HIV-infected women living in western countries, the CC screening guidelines normally referred to are those for the treatment and prevention of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents endorsed by the CDC, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and HIV Medicine Association (HIVMA) of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. The common denominator to these guidelines is the prevention of CC by screening, management of women with positive test results, and subsequent treatment of histologically confirmed high-grade cancer precursors. According to these recommendations, HIV-infected women should undergo 2 Pap smears within the first year after diagnosis of HIV infection, followed by annual Pap testing regardless of their age.Citation78,Citation79 As opposed to HIV-uninfected women, whose HPV prevalence progressively decreases with age, HIV-positive women have an HPV prevalence that remains high across different age groups, which justifies the decision to not yet define the age at which to interrupt screening for these women.Citation80 Differently from their HIV-negative counterpart, HIV-positive women should undergo screening within 1 year of the onset of sexual activity even if <21 years of age.Citation81

Similar to the guidelines that apply to high-income countries, the WHO recommendations also advise to start screening for CC as soon as the onset of sexual activity for women living in areas where the HIV prevalence is high and whose HIV status is either positive or unknown.Citation82 Although the recent implementation of HPV testing justifies the prolongation of the screening interval from 3 to 5 years for screen-negative women, such consideration only applies to HIV-negative women.Citation57,Citation83 Despite the lack of evidence coming from LMIC, the higher risk of developing cervical precancerous and cancerous lesions for HIV-infected women justifies a closer follow-up schedule. The WHO currently suggests repeating screening after 3 years in presence of a negative screening test for this high-risk group of women.Citation82

Although evidence on the subject is currently limited, the recurrence rates of CIN among HIV-infected women following standard excisional treatment have been proven to range from 20% to 75%.Citation84 The results of a retrospective cohort study have shown a recurrence rate of 18% among HIV-positive women treated with thermocoagulation and followed for a 4-year period. This result was not significantly different from that obtained for HIV-negative women in the same cohort.Citation85

Despite the literature gap on the subject, it seems evident that a closer follow-up schedule is advised for women who either test positive at primary screening or who are treated for a cervical premalignant lesions. What current knowledge seems to suggest, however, is that the timing of such follow-up visits should be no different than that applied to HIV-negative women.

Conclusion

To date, the best CC screening approach for HIV-infected women living in sub-Saharan Africa, where the HIV epidemic reaches its peak, has yet to be defined. As the risks-benefits balance does not seem to weight more toward a certain screening strategy for HIV-infected women, current evidence suggests that the screening options applied to HIV-negative women should be extended to their HIV-positive counterparts. The higher risk of developing cervical precancerous and cancerous lesions, however, imposes a closer follow-up schedule for this group of women.Citation82 The lack of sufficient evidence on the subject limits the reliability of the current CC screening guidelines for HIV-infected women and, thus, imposes the need to conduct further studies in order to provide more solid foundations for the prevention of a disease that currently represents a public health issue.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- NgonoGEvinaFEnquête Démographique et de Santé et Indicateurs Multiples du CamerounClaverton, Maryland, USAINS & ICF International2011

- AllemaniCWeirHKHarewoodRGlobal surveillance of cancer survival 1995–2009: analysis of individual data for 25,676,887 patients from 279 population-based registries in 67 countries (CONCORD-2)Lancet20153859972977101025467588

- CatarinoRVassilakosPTebeuPMSchaferSBongoeAPetignatPRisk factors associated with human papillomavirus prevalence and cervical neoplasia among Cameroonian womenCancer Epidemiol201640606626625088

- data.worldbank.org [homepage on the Internet]The World Bank Group2016 Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.AIDS.ZSAccessed September 29, 2016

- MbulaiteyeSMBhatiaKAdebamowoCSascoAJHIV and cancer in Africa: mutual collaboration between HIV and cancer programs may provide timely research and public health dataInfect Agent Cancer201161161822004990

- ShibuyaKMathersCDBoschi-PintoCLopezADMurrayCJGlobal and regional estimates of cancer mortality and incidence by site: II. Results for the global burden of disease 2000BMC Cancer200223712502432

- FitzmauriceCDickerDPainAThe global burden of cancer 2013JAMA Oncol20151450552726181261

- FerlayJSoerjomataramIErvikMGLOBOCAN 2012 v1.1, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet] Available from: http://globocan.iarc.frAccessed July 22, 2016

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)The Gap Report 2014UNAIDSGeneva, Switzerland2014 Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdfAccessed August 3, 2016

- CrosbieEJEinsteinMHFranceschiSKitchenerHCHuman papillomavirus and cervical cancerLancet2013382989588989923618600

- SteinLUrbanMIO’ConnellDThe spectrum of human immunodeficiency virus-associated cancers in a South African black population: results from a case-control studyInt J Cancer200812222602265

- ChoudhurySAChoudhuryNAHumphreyADHigher prevalence of Human Papillomavirus-related cervical precancerous abnormalities in HIV-infected compared to HIV-uninfected womenJ Natl Med Assoc201610811023

- NgandweCLoweJJRichardsPJHauseLWoodCAngelettiPCThe distribution of sexually transmitted Human Papillomaviruses in HIV positive and negative patients in ZambiaBMC Infect Dis200777717634108

- CliffordGMFranceschiSKeiserOImmunodeficiency and the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3 and cervical cancer: a nested case-control study in the Swiss HIV cohort studyInt J Cancer201613871732174026537763

- BekoloCEO’BryanGTchagoFENangueCBekoulePSKolloBIntegrating cervical cancer screening with HIV care in Cameroon: comparative risk analysis of cervical disease in HIV-infected women recieving antiretroviral therapy to women in the general populationPLoS One2016112e014915226866371

- BucciardiniRFragolaVAbegazTRetention in care of adult HIV patients initiating antiretroviral therapy in Tigray, Ethiopia: a prospective observational cohort studyPLoS One2015109e013611726340271

- YayaILandohDESakaBPredictors to adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV and AIDS at the regional hospital of Sokode, TogoBMC Public Health201414130825526773

- CobucciRNLimaPHde SouzaPCAssessing the impact of HAART on the incidence of defining and non-defining AIDS cancers among patients with HIV/AIDS: a systematic reviewJ Infect Public Health20148111025294086

- World Health OrganisationGuideline on When to Start Antiretroviral Therapy and On Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIVWHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataWHO PressGeneva, Switzerland2015

- BendavidEBhattacharyaJThe President’s Emergency plan for AIDS relief in Africa: an evaluation of outcomesAnn Intern Med20091501068866519349625

- World Health OrganizationComprehensive Cervical Cancer Control: A Guide to Essential Practice2nd edWHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataWHO PressGeneva, Switzerland2014

- SinayobyeJASklarMHooverDRPrevalence and risk factors for high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) infection among HIV-infected and uninfected Rwandan women: implications for hrHPV-based screening in RwandaInfect Agents Cancer201494025926864

- SafaeianMKiddugavuMGravittPEPrevalence and risk factors for carcinogenic human papillomavirus infections in rural Rakai, UgandaSex Transm Infect200884430631118385223

- MoodleyJRHoffmanMCarraraHHIV and pre-neoplastic and neoplastic lesions of the cervix in South Africa: a case-control studyBMC Cancer2006613516719902

- WoodmanCBCollinsSIYoungLSThe natural history of cervical HPV infection: unresolved issuesNat Rev Cancer200771112217186016

- SegondyMKellyHDjimaFPerformance of careHPV for detecting high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia among women living with HIV-1 in Burkina Faso and South Africa: HARP studyBr J Cancer2016115442543027434037

- JemalACenterMMDeSanctisCWardEMGlobal patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trendsCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev20101981893190720647400

- JemalAFedewaSAIs the prevalence of ER-negative breast cancer in the US higher among Africa-born than US-born black women?Breast Cancer Res Treat2012135386787322915073

- ChungMHMcKenzieKDe VuystHComparing papanicolau smear, visual inspection with acetic acid and human papillomavirus cervical cancer screening methods among HIV-positive women by immune status and antiretroviral therapyAIDS201327182909291923842133

- MaimanMTarriconeNVieiraJSuarezJSerurEBoyceJGColposcopic evaluation of human immunodeficiency virus seropositive womenObstet Gynecol199178184881675456

- FinkMJFrucherRGMaimanMThe adequacy of cytology and colposcopy in diagnosing cervical neoplasia in HIV-seropositive womenGynecol Oncol19945511331377959254

- SankaranarayananRBudukhAMRajkumarREffective screening programmes for cervical cancer in low- and middle-income developing countriesBull World Health Organ2001791095496211693978

- HuchkoMJSnedenJLeslieHHA comparison of two visual inspection methods for cervical cancer screening among HIV-infected women in KenyaBull World Health Organ201492319520324700979

- CronjéHSScreening for cervical cancer in developing countriesInt J Gynecol Obstet2004842101108

- AndersonJWysongMEstepDEvaluation of cervical cancer screening programs in Côte d’Ivoire, Guyana and Tanzania: effect of HIV statusPLoS One2015109e013924226405784

- HuchkoMJSnedenJSawayaGAccuracy of visual inspection with acetic acid to detect cervical cancer precursors among HIV-infected women in KenyaInt J Cancer2015136239239824889387

- ShiferawNSalvador-DavilaGKassahunKThe single-visit approach as a cervical cancer prevention strategy among women with HIV in Ethiopia. Successes and lessons learnedGlob Health Sci Pract201641879827016546

- MartinCETergasAIWysongMReinselMEstepDVaralloJEvaluation of a single-vsit approach to cervical cancer screening and treatment in Guyana: feasibility, effectiveness and lessons learnedJ Obstet Gynaecol Res20144061707171624888938

- OdafeSTorpeyKKhamofuHIntegrating cervical cancer screening with HIV care in a district hospital in Abuja, NigeriaNiger Med J201354317618423901180

- AudetCMSilva MatosCBlevinsMCardosoAMoonTDSidatMAcceptability of cervical cancer screening in rural MozambiqueHealth Educ Res201227354455122307215

- MwanahamuntuMHSashasrabuddheVVBlevinsMUtilisation of cervical cancer screening services and trends in screening positivity rates in a “screen-and-treat” program integrated with HIV/AIDS care in ZambiaPLoS One201389e7460724058599

- SankaranarayanRNeneBMDinshawKAA cluster randomized controlled trial of visual, cytology and human papillomavirus screening for cancer of the cervix in rural IndiaInt J Cancer2005116461762315818610

- QiaoLLiBLongMWangXWangAZhangGAccuracy of visual inspection with acetic acid and with Lugol’s iodine for cervical cancer screening. Meta-analysisJ Obstet Gynaecol Res20154191313132526014371

- DeGregorioGABradfordLSMangaSPrevalence, predictors and same day treatment of positive VIA enhanced by digital cervicography and histopathology results in a cervical cancer prevention programPLoS One2016116e015731927280882

- FirnhaberCMaoLLevinSEvaluation of a cervicography-based program to ensure quality of visual inspection of the cervix in HIV-infected women in Johannesburg, South AfricaJ Low Gen Tract Dis2015191711

- MwanahamuntuMSahasrabuddheVKapambweSAdvancing cervical cancer prevention initiatives in resource-constrained settings: insights from the Cervical Cancer Prevention Program in ZambiaPLoS Med201185e100103221610859

- Lince-DerocheNPhiriJMichelowPSmithJSFirnhaberCCosts and cost effectiveness of three approaches for cervical cancer screening among HIV-positive women in Johannesburg, South AfricaPLoS One20151011e014196926569487

- DolmanLSauvagetCMuwongeRSankaranarayananRMeta-analysis of the efficacy of cold coagulation as a treatment method for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a systematic reviewBJOG2014121892992424597779

- SanjaranarayanRBasuPWesleyRSAccuracy of visual screening for cervical neoplasia: results from an IARC multicenter study in India and AfricaInt J cancer2004110690791315170675

- ChibweshaCJFrettBKatunduKClinical performance validation of 4 point-of-care cervical cancer screening tests in HIV-infected women in ZambiaJ Low Gen Tract Dis2016203218223

- DennyLAnorluRCervical cancer in AfricaCancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev20122191434143822806169

- EinsteinMHSmithKMDavisTEClinical evaluation of the cartridge-based GeneXpert human papillomavirus assay in women referred for colposcopyJ Clin Microbiol20145262089209524719440

- McDonaldATergasAIKuhnLDennyLWrightTCJrDistribution of human papillomavirus genotypes among HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in Cape Town, South AfricaFront Oncol201444824672770

- Giorgi-RossiPFranceschiSRoncoGHPV prevalence and accuracy of HPV testing to detect high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasiaInt J Cancer201213061387139421520039

- FranceschiSHerreroRCLiffordGMVariations in the age-specific curves of human papillomavirus prevalence in women worldwideInt J Cancer2006119112677268416991121

- SchiffmanMWentzensenNWacholderSKinneyWGageJCCastlePEHuman papillomavirus testing in the prevention of cervical cancerJ Natl Cancer Inst2011103536838321282563

- SaslowDSolomonDLawsonHWAmerican Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention of early detection of cervical cancerAm J Clin Pathol2012137451654222431528

- MujuniFMiramboMMRambauPVariability of high risk HPV genotypes among HIV infected women in Mwanza, Tanzaniathe need for evaluation of current vaccine effectiveness in developing countriesInfect Agent Cancer2016114927547239

- CattaniPZannoniGFRicciCClinical performance of human papillomavirus E6 and E7 mRNA testing for high-grade lesions of the cervixJ Clin Microbiol200947123895390119828739

- De VuystHFranceschiSPlummerMMethylation levels of CADM1, MAL, and MIR124-2 in cervical scrapes for triage of HIV-infected, high-risk HPV-positive women in KenyaJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr201570331131826473640

- Del GobboABonoldiECribiu’FMInsuline-like growth factor II mRNA binding protein 3 (IMP3) expression in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and its relationship with HIV-infection statusSex Health2015121222625427240

- GravittPERositchAFHPV self-testing and cervical cancer screening coverageLancet Oncol201415212812924433681

- SnijdersPJVerhoefVMAbrynMHigh-risk HPv testing on self-sampled versus clinician-collected specimens: a review on the clinical accuracy and impact on population attendance in cervical cancer screeningInt J Cancer2013132102223223622907569

- ArbynMVerdootFSnijdersPJAccuracy of human papillomavirus testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples: a meta-analysisLancet Oncol201415217218324433684

- AdamsonPCHuchkoMJMossAMKinkelHFMedina-MarinoAAcceptability and accuracy of cervical cancer screening using a self-collected tampon for HPV messenger-RNA testing among HIV-infected women in South AfricaPLoS One2015109e013729926332236

- MurphyJMarkHAndersonJFarleyJAllenJA randomized trial of human papillomavirus self-sampling as an intervention to promote cervical cancer screening among women with HIVJ Low Gen Tract Dis2016202139144

- SerwaddaDWawerMJShahKVUse of a Hybrid capture assay of self-collected vaginal swabs in rural Uganda for detection of human papillomavirusJ Infect Dis199918041316131910479163

- GakidouENordhagenSObermeyerZCoverage of cervical cancer screening in 57 countries: low average levels and large inequalitiesPLoS Med200856e13218563963

- LouieKSde SanjoseSMazaudPEpidemiology and prevention of human papillomavirus and cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: a comprehensive reviewTrop Med Int Health200914101287130219772550

- DuerrAKiekeBWarrenDHuman papillomavirus-associated cervical cytologic abnormalities among women with or at risk of infection with human immunodeficiency virusAm J Obstet Gynecol2001184458459011262457

- BukirwaAMutyobaJNMukasaBNMotivations and barriers to cervical cancer screening among HIV infected women in HIV care: a qualitative studyBMC Womens Health2015158226458898

- BayuHBerheYMulatAAlemuACervical cancer screening service uptake and associated factors among age eligible women in Mekelle Zone, Northern Ethiopia, 2015: A community based study using health belief modelPLoS One2016113e014990826963098

- FletcherFEBuchbergMSchoverLRPerceptions of barriers and facilitators to cervical cancer screening among low-income, HIV-infected women from an integrated HIV clinicAIDS Care201426101229123524635664

- KumakechEAnderssonSWabingaHBerggrenVIntegration of HIV and cervical cancer screening perceptions of healthcare providers and policy makers in UgandaBMC Public Health20141481025099996

- OgunwaleANColemanMASangi-HaghpeykarHAssessment of factors impacting cervical cancer screening among low-income women living with HIV-AIDSAIDS Care201628449149426493859

- Orango’oEOWachiraJAsirwaFCFactors associated with uptake of visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) for cervical cancer screening in Western KenyaPLoS One2016116e015721727310005

- FrazierELSuttonMYTieYMcNaghtenADBlairJMSkarbinskiJScreening for cervical cancer and sexually transmitted diseases among HIV-infected womenJ Womens Health (Larchmt)201625212413226447835

- MoscickiABCoxJTPractice improvement in cervical screening and management (PICSM): symposium on management of cervical abnormalities in adolescents and young womenJ Low Genit Tract Dis2010141738020043357

- AIDSinfoGuidelines for Prevention and treatment of opportunisitc infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV medicine association of the infectious diseases society of AmericaMMWR200958RR-41207

- MbulawaZZACoetzeeDWilliamsonALHuman papillomavirus prevalence in South African women and men according to age and human immunodeficiency virus statusBMC Infect Dis20151545926502723

- KellerMJScreening for human papillomavirus-associated cervical disease in HIV-infected womenTop Antivir Med201523414214526713504

- SantessoNMustafaRASchünemannHJWorld Health Organization guidelines for treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2–3 and screen-and-treat stretegies to prevent cervical cancerInt J Gyn Obstet20161323252258

- AdlerDHWallaceMBennieTCervical dysplasia and high-risk human papillomavirus infections among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected adolescent females in South AfricaInfect Dis Obstet Gynecol2014201449804825389377

- TebeuPMMajorALMhawechPRapitiEThe recurrence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV-positive women: a review of the literatureInt J STD AIDS200617850751116925893

- OgaEABrownJPBrownCRecurrence of cervical intraepithelial lesions after thermo-coagulation in HIV-positive and HIV-negative Nigerian womenBMC Womens Health2016162527169666

- HotezPJFenwickAKjetlandEFAfrica’s 32 cents solution for HIV-AIDSPLoS Negl Trop Dis200935e43019479041

- FerlayJShinHRBrayFFormanDMathersCParkinDMGLOBOCAN 2008, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10 [Internet]Lyon, FranceInternational Agency for Research on Cancer2010 Available from: https://www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/iarcnews/2010/globocan2008.phpAccessed January 13, 2017

- AkinwuntwanLAdesinaOAOkoloCACorrelation of cervical cytology and visual inspection with acetic acid in HIV-positive womenJ Obstet and Gynaecol200828663864119003664

- MabeyaHKhozaimKLiuTComparison of conventional cervical cytology versus visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) amon HIV-infected women in western KenyaJ Low Gen Tract Dis20121629297

- KuhnLWangCTsaiWYWrightTCDennyLEfficacy of human papillomavirus-based screen-and-treat for cervical cancer prevention among HIV-infected womenAIDS201024162553256120706107

- FirnhaberCMayiselaNMaoLValidation of cervical cancer screening methods in HIV positive women from Johannesburg South AfricaPLoS One201381e5349423326441

- DartellMARaschVIfnerTPerformance of visual inspection with acetic acid and human papillomavirus testing for detection of high-grade cervical lesions in HIV positive and HIV negative Tanzanian womenInt J Cancer2014135489690424391021

- NgouJGIlhamCOmarTComparison of analytical and clinical performances of the digene HC2 HPV DNA assay and the INNO-LiPA HPV genotyping assay for detecting high-risk HPV infection and cervical neoplasia among HIV-positive African womenJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr2010682162168