Abstract

Purpose

Realizing aspirations for meeting the global reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health goals depends not only on increasing the numbers but also on improving the capability of midwifery workforce. We conducted a task analysis study to identify the needs for strengthening the midwifery workforce in Ethiopia.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of recently qualified midwives in Ethiopia. Purposively selected participants from representative geographic and practice settings completed a self-administered questionnaire, making judgments about the frequency of performance, criticality, competence, and location of training for a list of validated midwifery tasks. Using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Version 20, we computed the percentages and averages to describe participant and practice characteristics. We identified priority preservice education gaps by considering the tasks least frequently learned in preservice, most frequently mentioned for not being trained, and had the highest not capable response. Identification of top priorities for in-service training considered tasks with highest “not capable” and “never” done responses. We determined the licensing exam blueprint by weighing the composite mean scores for frequency and criticality variables and expert rating across practice categories.

Results

One hundred and thirty-eight midwives participated in the study. The majority of respondents recognized the importance of midwifery tasks (89%), felt they were capable (91.8%), reported doing them frequently (63.9%), and learned them during preservice education (56.3%). We identified competence gaps in tasks related to obstetric complications, gynecology, public health, professional duties, and prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV. Moreover, our study helped to determine composition of the licensing exam for university graduates.

Conclusion

The task analysis indicates that midwives provide critical reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health care services and supports continuing investment in this cadre. However, there were substantial competence gaps that limit their ability to accelerate progress toward health development goals. Moreover, basing the licensure exam on task analysis helped to ground it in national practice priorities.

Introduction

Calls for transforming and scaling up the health workforce as a prerequisite for strengthening health systems and accelerating progress toward universal health coverage have never been stronger.Citation1–Citation4 It has also become clear that realizing aspirations for universal health coverage depends not only on increasing workforce numbers but also on improving its capability. Health system challenges in the 21st century require comprehensive health workforce strategies that transform performance and quality along with availability, accessibility, and acceptability.Citation2

In the context of attaining national and international development goals for maternal and child health, this means transforming the midwifery workforce. With mounting evidence indicating reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health (RMNCH) services by competent midwives can avert most maternal deaths, stillbirths, and newborn deaths, the preferred policy option is to invest in the midwifery workforce.Citation5–Citation8 Accordingly, many high-mortality, low- and middle-income countries have scaled up education and deployment of midwives.Citation8,Citation9 In Ethiopia, the number of midwives dramatically increased from 1,379 in 2008 to 9,244 in 2014.Citation10 This is due to rapid expansion of midwifery education resulting in annual graduation outputs rising above 2,000. There are three types of undergraduate midwifery education programs in Ethiopia: direct entry university program leading to degree, direct entry vocational program leading to diploma, and postbasic nurse-midwife vocational program leading to diploma qualification.Citation11

However, there is limited published data on the actual work of recently deployed midwives. Without such research evidence, it is difficult to know the effectiveness of current strategies and to improve the capability of midwives. Task, job, or practice analysis is a systematic assessment of knowledge and skills that characterize a professional practice.Citation12 As such, a task analysis study can generate evidence on current performance of midwives and thereby serve as a data-driven method to identify the needs for strengthening the midwife workforce. We conducted this study to analyze actual on-the-job performance of midwives, identify the needs for strengthening midwifery education and training, and guide licensing exam blueprint development.

Materials and methods

Design

We conducted a cross-sectional study from December 9 to 13, 2013 to analyze the tasks performed by practicing midwives in Ethiopia.

Setting

Midwives from the four most populous and agrarian regions (Tigray, Amhara, Oromia, and Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples), two of the three urban regions (Addis Ababa, Harari), and one of the four relatively less-developed regions (Somali) participated in the study, covering seven out of the eleven regional states and city administrations, home to 96% of Ethiopia’s population.

Participants

Recently qualified midwives with 6 months to 4 years of work experience participated in the study. The rationale for limiting the experience to 4 years was to obtain data that reflect midwives’ preservice education (PSE) and recent in-service training, rather than expertise gathered over long years of practice. Midwives having <6 months experience were also excluded, as they were not expected to have enough practice and training opportunities to make meaningful judgments. Each respective regional health bureau sent invitation letters to geographically representative health centers and hospitals in their jurisdiction to identify eligible midwives for recruitment. Each facility, in turn, purposively selected one appropriate midwife to participate in the study.

Variables

We drafted a midwifery task list from national scopes of practice, curricula, and job descriptions and validated it in a national expert panel workshop. The expert panel included midwifery educators and practitioners from different institutions, as well as representatives from the Federal Ministry of Health and the Ethiopian Midwifery Association. The final task list had 86 midwifery tasks including professional duties, general service delivery tasks, reproductive and maternity care tasks, labor and delivery tasks, and community/public health tasks. Three tasks were excluded later, as they were thought to be outside of midwifery scope of practice. Study participants made four judgments about each task. The first question was about frequency (how often did a participant perform a task?). The possible responses were daily (completed a task at least once per day), weekly (completed a task less often than daily, but at least once per week), monthly (completed a task less often than weekly, but at least once per month), rarely (completed a task less often than monthly), and never (lacked the opportunity or capability to perform a task). The second question concerned criticality (how critical is timely and effective performance of a task for client and/or population health outcomes?). The response options were high (failure to complete a task correctly or in a timely manner will lead to client death, permanent disability, or major impact on public health), moderate (failure to complete a task correctly or in a timely manner may lead to serious client discomfort, short-term disability, or moderate impact on public health), and low (failure to complete a task correctly or in a timely manner will lead to minimal impact on client or public health). The third question was about performance (how competent is the participant in performing a task?). The possible responses were proficient (expert at a task or can perform a task so well that s/he feels comfortable supervising others), competent (capable of performing a task safely, although may ask for supervision from a more experienced provider), and not capable (not comfortable performing a task; may cause harm if a task is performed without supervision). The fourth question concerned location or timing of training (when and where did the participant learn to perform a task?). The response options were PSE (received formal training as part of the PSE), in-service training (received formal training at some point after graduation), on-the-job training (received informal training from coworkers or supervisor, once began working), and not trained (received no formal or informal training for a task). We also collected data on sociodemographic variables including age, sex, region, qualification (diploma or bachelor degree), type of facility (health center or hospital), and length of work experience.

Measurement

We used a structured self-administered questionnaire with a validated task list to collect data. In each region, the study participants gathered at one place for a data collection workshop and completed the questionnaires individually with facilitation support from an expert midwife. Data collectors verified eligibility of study participants before the start of data collection workshops.

Data analysis

We used Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Version 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for data analysis. Descriptive statistics included frequencies and means for the four key variables and sociodemographic characteristics. Further analysis examined response combinations to identify priority areas for PSE strengthening, in-service training, and licensing exam development. We identified priority PSE gaps by selecting critical tasks with a combination of relatively low “trained in PSE”, high “not trained”, and high “not capable” responses. Top needs for in-service training prioritized critical tasks with high percentage of responses for “not capable” and “never done”.

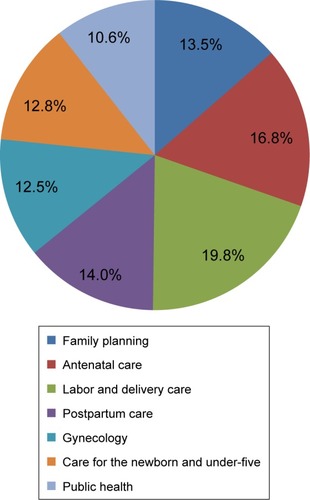

We considered responses to “criticality” and “frequency” variables to determine the level of emphasis in midwifery licensing exam.Citation12 Grouped task lists in seven categories represented broad midwifery practice areas, namely, family planning, antenatal care, labor and delivery, postpartum care, gynecology care, care for the newborn and under-five child, and community/public health. We then applied the following steps to determine the percentage distribution of exam among the seven categories. First, we calculated the mean frequency and criticality score for each task, ranging from 1 (denoting never) to 5 (denoting daily) and from 1 (denoting low criticality) to 3 (denoting high criticality), respectively. We then calculated the composite mean score for each task (range was 2–8). We reviewed tasks with borderline composite mean scores (3< “X” <5) for possible elimination and calculated the average of composite mean scores for each category. Finally, we summed the category averages and computed the proportion of each category out of the total.

We complemented results from the task analysis study with subjective ratings from 32 experts during licensing exam writing workshop in February 2015. Item writers assigned percentage weight to each of the seven categories. We computed the mean of the expert assessments for each category and averaged it with the results from the survey.

Data quality assurance

The task list was developed based on national documents and validated in an expert panel workshop. A 5-day data collection training was conducted prior to field work. Training topics included introduction to task analysis methodology, study protocol, data storage, and ethical issues. Participants practiced data collection techniques in a role-play format after discussing the task list. Proficient midwives recruited from each region facilitated the data collection workshop and experts from the Federal Ministry of Health, Ethiopian Midwifery Association, and Jhpiego supervised the data collection process.

Ethical clearance

We obtained ethical clearance for the study from the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board Office and approval from the Ethiopian Ministry of Health and respective regional health bureaus. Informed verbal consent was also obtained from the study participants prior to data collection.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

One hundred and thirty-eight midwives selected from six regional states and one city administration participated in the study, giving a response rate of 98.6% (138/140). With regard to sociodemographic characteristics, majority of the respondents were females (80.4%), younger than 25 years (62.3%), had a diploma/vocational qualification (81.9%), worked in health centers (60.9%), and had 2 years or less of work experience as a midwife (58%). The mean duration of service was 2.6 years ().

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants (N=138)

Analysis of tasks performed by recently qualified midwives

summarizes the responses of study participants to frequency, criticality, competence, and timing/location of training questions by competency domain. Approximately 90% of respondents recognized the importance of midwifery tasks and felt they were capable of performing them. More than half of them also reported performing midwifery tasks frequently and having learned them during PSE. Furthermore, the majority of study participants said they provided family planning (58.7%), antenatal care (73.2%), normal delivery (82.6%), postpartum care (76.8%), and essential newborn care (79.7%) services on a daily basis (data not shown).

Table 2 Analysis of tasks performed by recently qualified midwives in terms of frequency, criticality, competence, and location of training

Although all tasks were deemed critical by the vast majority (85.2%–92.7%) of study participants, more than 10% of respondents rated all but antenatal care, normal labor and delivery, and child health care tasks as of low importance. Likewise, although an overwhelming majority (81.3%–97.3%) said they were capable of performing midwifery tasks, a sizable proportion (11.2%–18.7%) reported competence gaps in gynecology, obstetric complications, and community/public health tasks. These three task categories were also the least frequently performed tasks. Although PSE was the predominant time of learning, a substantial percentage (28.8%–50.0%) of respondents learned midwifery tasks by in-service training and informal on-the-job learning. The in-service/on-the-job modalities played a particularly prominent role in learning HIV/prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) competencies and professional duties. Gynecology, public health, and obstetric complications had notable response rates (9.5%–12.0%) for never being trained.

Gaps in education and needs for training

summarizes the top 20 gaps in preservice midwifery education. Twenty critical tasks had relatively low “trained in PSE”, high “not trained”, and high “not capable” responses. The least frequently learned tasks in PSE were membership in professional association, participating in policy dialog, training and supervising community health workers (CHWs), and performing manual vacuum aspiration (MVA). The most frequently mentioned tasks for “not trained” were detecting reproductive organ cancers and tumors, performing MVA, membership in professional association, identifying injuries of pelvic muscles, surveillance of maternal and newborn health conditions, training and supervising CHWs, and preparing and assisting with operations. The biggest competence gaps (hence top in-service training needs) were in detecting reproductive organ cancers and tumors, performing MVA, assisting with operations, identifying pelvic muscle injuries, membership in professional association, diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy, diagnosis and management of abortion, induction and augmentation, and identifying, counseling, and preventing infertility.

Table 3 Top 20 gaps in preservice midwifery education

Exam blueprint for midwifery licensing exam

The results from the task analysis study suggested the midwifery licensing exam composition to include 14.9% family planning, 15.1% antenatal care, 14.7% labor and delivery, 15.3% postpartum care, 13.2% gynecology, 14.5% newborn and child health, and 12.4% public health questions. Expert ratings during item writing workshop for licensing exam generated higher emphasis for antenatal (+3.4 points) and labor and delivery (+10.2 points) categories, but lesser emphasis for family planning (−2.7 points), postpartum (−2.4 points), gynecology (−1.6 points), under-five (−3.5 points), and public health (−3.8 points) categories. Averaged percentages from the task analysis study and the expert ratings resulted in a final exam distribution plan composed of labor and delivery, antenatal care, postpartum care, family planning, care for the newborn and under-five child, gynecology, and public health questions, in decreasing frequency ().

Discussion

Our study examined midwifery practice and generated evidence to strengthen midwifery education, care, and regulation. Strengths of the study include use of a nationally representative sample from geographic and practice settings for midwives working in the public sector. A limitation to task analysis surveys is that the data is self-reported and there is potential for responses to be ones that the respondents considered most acceptable. We tried to mitigate this with assurance to the study participants that their responses would not be linked to their names and that reporting would be aggregate. Another limitation was that some of the tasks were not discrete enough, making interpretation less straightforward.

The proportion of male midwives in our study might appear high compared to other countries, but it reflects the Ethiopia midwifery workforce and is consistent with a previous study conducted with graduating midwifery students.Citation11

Our results confirmed that midwives are crucial providers of reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health care services. This supports the Ethiopian government’s policy strategy to scale up midwifery education. Most midwives not only understood the significance of their tasks to health and well-being of women and children but also reported that they performed them competently and routinely. Study participants participated in gynecology, public health, and obstetric complications management less often, probably due to a combination of lack of opportunity and capability (). Task analysis studies from sub-Saharan African countries have also reported largely similar findings. A Liberian study reported that most (60%–80%) midwives completed their tasks frequently, except for obstetric complications and child health interventions.Citation13 A Malawi study found that majority of nurse-midwife technicians were competent in midwifery and infectious diseases and performed them frequently, but were not competent at the less common tasks related to cancer, public health, and obstetric complications.Citation14 Majority of maternal and child health nurses (57.9%–75.1%) in Mozambique frequently provided antenatal, labor and delivery, newborn and postpartum care, but rarely participated in complications management, gynecology, and public health.Citation15

Our study revealed the presence of significant gaps in the content and quality of preservice midwifery education in the areas of obstetric complications, gynecology, public health, professional duties, and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. A large proportion of respondents did not learn several tasks that are within expected midwifery practice in PSE. A number of tasks learned in PSE also had low levels of reported competence (). Even though small, the percentage of participants who thought midwifery tasks were of low importance was not negligible. This is potentially a concern, as midwives may not want to learn and do tasks that they think are less important. Lack of appreciation of task importance might be due to lack of knowledge, which possibly indicates a need for greater emphasis in PSE ().

The weakness we found in preservice midwifery education is consistent with findings from other studies in Ethiopia, Africa, and Asia. Assessment of graduating midwifery students in Ethiopia showed low achievement of competencies, particularly in performance of MVA, vacuum-assisted delivery, partograph use, and integrated management of childhood illnesses.Citation11 A mixed methods study identified insufficient PSE as a key barrier to provision of quality emergency obstetric care in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.Citation16 A task analysis of nurse-midwife technicians in Malawi reported low levels of competence in obstetric complications management.Citation14 A similar study in Liberia found that 13%–20% of midwives did not receive PSE on some antenatal, normal delivery, and postnatal care tasks.Citation13 A study in Mali reported that midwives scored 66.4% on assessment of emergency obstetric care knowledge and skills using clinical vignettes.Citation17 Evaluation of midwifery graduates’ performance in Afghanistan found gaps in retention of clinical competencies with more pronounced deficits in shock management and MVA.Citation18 An Indian study indicated that final year midwifery students had low level of confidence in basic midwifery competencies for antepartum, intrapartum, postpartum, and newborn care.Citation19 The State of the World’s Midwifery Report 2014 covering 73 low- and middle-income countries also found pervasive gaps in midwifery education.Citation8

The possible gaps in PSE and competence of midwives have important implications. The substantial gaps in management of obstetric complications are particularly critical in view of their importance for maternal and newborn survivalCitation20,Citation21 and the global commitment to end preventable maternal and child deaths.Citation22 Reproductive organ cancers are also a leading cause of morbidity and mortality for women in low- and middle-income countries.Citation23 Breast, cervical, and ovarian cancers are the most common cancers among Ethiopian women and account for half of cancer-related deaths.Citation24 The capacity gap for detecting reproductive organ cancers is significant as it constrains the ability to increase access to screening and treatment services in Ethiopia.Citation25 Infertility is also a major, but neglected public health problem in low-income countries including Ethiopia.Citation26 Prevention and treatment services are limited, partly due to lack of trained staff.Citation27–Citation29 As key reproductive health care providers, midwives should be able to provide basic infertility prevention, diagnostic, and treatment services. Violence against women is also a pervasive public health problem with impacts on sexual, reproductive, and perinatal health outcomes.Citation30 As women’s health care providers, midwives have an important role to play in identifying victims of violence and providing clinical care.Citation31

Midwives can contribute even more to strengthen health systems and improve RMNCH outcomes if they actively participate in public health, research, and policy activities beyond clinical care. Addressing the gaps in preservice content for these areas is important to increase midwifery participation.Citation32–Citation35 Health promotion and disease prevention are central to midwifery practice,Citation5,Citation36 and midwives need public health knowledge and skills to carry out this function effectively. Improving the health of women and children requires understanding the social determinants of health and partnership,Citation37 which in turn require public health and policy advocacy skills. The education gap in preparing midwives to train and supervise CHWs represents a missed opportunity because health extension workers (who are the CHWs in Ethiopia) are the frontline RMNCH care providers for the rural Ethiopian population.Citation38,Citation39 Midwives are expected to support and collaborate with them in promoting and providing family health services such as family planning, antenatal care, assisted delivery, vaccination, and treatment of common childhood illnesses.

The International Confederation of Midwives regards organization of midwives in an association as one of the three pillars for a strong midwifery profession and an important force to improve the health of women and children.Citation40 However, our study clearly indicated that PSE seldom addressed membership in professional association and, possibly consequently, the majority of respondents were not members of a professional association. A significant percentage did not believe membership was important. The perception gap may be an indication that midwives did not believe they would benefit from membership in a professional association, which suggests that the local midwifery association needs to do more to educate and attract midwives. Membership in a professional association may strengthen professional identity and increase motivation and performance.Citation41

Ethiopia is one of the 22 countries with the highest number of pregnant women living with HIV. In view of the increased efforts required to achieve the global goal of eliminating new child infections,Citation42 the inadequacy in PMTCT education and competence is significant. In-service training appears to have played a bigger role than PSE and compensated for much of the education gap in PMTCT. This, however, warrants further work to integrate the in-service content in preservice curriculum and improve competence in this area.

Midwives can have a great impact in improving RMNCH outcomes. Competent midwives can provide most of the essential care needed to prevent most maternal and newborn deaths.Citation5–Citation8 However, realizing the full benefits of midwifery care for the health and well-being of women and children requires reviewing and strengthening midwifery education with focus on priority gaps identified in our study.

Even more urgent is the need to enhance the capacity of the existing midwifery workforce. A substantial proportion of currently practicing midwives need opportunities for improving their competence in obstetric complications, reproductive organ cancers, and infertility. Because these are low-frequency events, opportunities for informal on-the-job learning and practice are limited. An alternative is requiring an in-service training intervention. Several studies from low-resource settings have demonstrated that it is feasible to train midlevel health workers to provide safe and effective emergency obstetric careCitation43–Citation49 and cervical cancer screening.Citation50,Citation51 Basic infertility prevention and management services can be offered in low-resource settings.Citation27–Citation29 We also know from literature that training delivered using effective techniques, repeated over time, and organized in a workplace-like setting can improve the performance.Citation52

Professional association meetings offer an important avenue to access continuing education. A challenge is the low membership rates reported by respondents. If local professional associations can inform and motivate potential members, it would be an important way to provide continuing education.

Conducting task analysis study is foundational for developing a valid and legally defensible licensing examination, as the content of a licensing examination should be closely related to the tasks that a health professional performs on the job.Citation12,Citation53,Citation54 The American Midwifery Certification BoardCitation12 and the National Council of State Boards of NursingCitation54 periodically conduct task analysis studies to guide development of exam content. Our findings suggested a licensing exam should systematically sample all areas of midwifery practice, including reproductive, maternal, and child health services to individuals and populations, but with greater emphasis on antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum care. This is consistent with test specification weights recommended in the latest task analysis by the American Midwifery Certification Board, which suggested a broad sampling of midwifery practice and greater emphasis on antepartum (22%), intrapartum (22%), and postpartum (16%) care.Citation12 Our findings served as the basis for development of a blueprint for the first national licensing exam for bachelor of science in midwifery, which was successfully administered in 2015. The exam provides a standard that new graduates must meet to enter the workforce. In addition, a licensing exam developed in this manner can improve the quality and relevance of midwifery education through feedback to midwifery schools.

Conclusion

Midwives are important providers of RMNCH services, and the Government of Ethiopia should continue to invest in midwifery as a key strategy to achieve national health development goals. However, there are substantial PSE gaps that need addressing through strengthening the content and quality of midwifery education with focus on obstetric complications, gynecology, public health, professional duties, and PMTCT in light of national and global priorities. Our study also revealed the presence of significant gaps in ability of the existing midwifery workforce to identify and/or manage obstetric complications, reproductive organ cancers, and infertility. Strengthening the existing midwifery workforce through targeted in-service training is urgently needed in order to realize the full potential of midwifery care to provide services to Ethiopian families. The majority of midwives were not a member of a professional association, indicating the need for greater effort by the national midwifery association to attract and recruit midwives. The Strengthening Human Resources for Health Project should support the Ministry of Health to revise midwifery curricula and develop need-based in-service training courses. The Ethiopian Midwifery Association could collaborate in these efforts and play a role in providing continuing education and in-service courses.

Our study also served as the primary basis for developing the first national licensing exam for graduates of bachelor of science in midwifery. This contributes to assuring the quality and relevance of midwifery education and the midwifery workforce. We recommend that task analysis be conducted periodically to inform continuous improvement of midwifery education and practice. Future studies should involve larger sample populations, apply probabilistic sampling procedure, and develop a more specific task list.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development under the Cooperative Agreement AID-663-A-12-0008. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of United States Agency for International Development or the US government. We are also grateful to the study participants and the Ministry of Health of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WHOTransforming and Scaling Up Health Professionals’ Education and Training: World Health Organization Guidelines 2013GenevaWorld Health Organization2013

- CampbellJDussaultGBuchanJA universal truth: no health without a workforce Forum report, Third Global Forum on Human Resources for Health, Recife, BrazilGenevaGlobal Health Workforce Alliance and World Health Organization2013

- AkikoMAraujoECashinCHarrisJIkegamiNReichMRUniversal Health Coverage for Inclusive and Sustainable Development: A Synthesis of 11 Country Case Studies Directions in DevelopmentWashington DCWorld Bank2014

- USAIDUSAID’s Vision for Health Systems Strengthening (2015–2019)Washington DCUnited States Agency for International Development2015

- RenfrewMJMcFaddenABastosMHMidwifery and quality care: findings from a new evidence informed framework for maternal and newborn careLancet20143841129114524965816

- HomerCSFribergIKDiasMABThe projected effect of scaling up midwiferyLancet20143841146115724965814

- Hoope-BenderPtBernisLdCampbellJImprovement of maternal and newborn health through midwiferyLancet20143841226123524965818

- UNFPAThe State of the World’s Midwifery 2014: A Universal Pathway A Woman’s Right to HealthNew YorkThe United Nations Population Fund, the International Confederation of Midwives, the World Health Organization2014

- Van LerbergheWMatthewsZAchadiECountry experience with strengthening of health systems and deployment of midwives in countries with high maternal mortalityLancet20143841215122524965819

- FMOHHuman Resource for Health Strategic Plan (2009–2025)Addis AbabaFederal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Health2015

- YigzawTAyalewFKimY-MHow well does pre-service education prepare midwives for practice: competence assessment of midwifery students at the point of graduation in EthiopiaBMC Med Educ20151513026271647

- AMCB2012 Task Analysis Report: A Report of Midwifery PracticeLinthicum, MDAmerican Midwifery Certification Board2012

- UdayaASubahMDrakeMNgCJohnsonPTask analysis: An evidence-based methodology for strengthening education and training of nurses and midwives in LiberiaInt J Nurs Midwifery201139118127

- JacobSHolmanJMsolombaRUsing task analysis to strengthen nursing and midwifery pre-service education in MalawiInt J Nurs Midwifery20157584103

- DgedgeMMendozaANecocheaEBossemeyerDRajaboMFullertonJAssessment of the nursing skill mix in Mozambique using a task analysis methodologyHum Resour Health201412524460789

- AustinAGulemaHBelizaMBarriers to providing quality emergency obstetric care in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: healthcare providers’ perspectives on training, referrals and supervision, a mixed methods studyBMC Pregnancy Childbirth2015157425885336

- HuchonCArsenaultCTourignyCObstetric competence among referral healthcare providers in MaliInt J Gynaecol Obstet20141261565924800659

- ZainullahPAnsariNYariKEstablishing midwifery in low-resource settings: guidance from a mixed-methods evaluation of the Afghanistan midwifery education programMidwifery201330101056106224290947

- SharmaBHildingssonIJohanssonEPrakasammaMRamaniKVChristenssonKDo the pre-service education programmes for midwives in India prepare confident ‘registered midwives’? A survey from IndiaGlob Health Action201582955326649550

- SayLChouDGemmillAGlobal causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysisLancet Glob Health20142e323e33325103301

- BhuttaZADasJKBahlRCan available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost?Lancet201438434737024853604

- WHOHealth in 2015: From MDGs, Millennium Development Goals to SDGs, Sustainable Development GoalsGenevaWorld Health Organization2015

- WHOWHO Guidance Note: Comprehensive Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control: A Healthier Future for Girls and WomenGenevaThe World Health Organization2013

- WHOCancer Country Profiles 2014, EthiopiaGenevaThe World Health Organization2014 Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/country-profiles/eth_en.pdf?ua=1Accessed December 30, 2015

- FMOHHealth Sector Transformation Plan (2015/2016–2019/2020)Addis AbabaFederal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Health2015 Available from: http://www.moh.gov.et/documents/26765/0/Health+Sector+Transformation+Plan/5542a23a-9bc7-46a2-8c1f-8b32c2603208?version=1.0Accessed December 30, 2015

- MascarenhasMNFlaxmanSRBoermaTVanderpoelSStevensGANational, regional, and global trends in infertility prevalence since 1990: a systematic analysis of 277 health surveysPLoS Med2012912e100135623271957

- HammarbergKKirkmanMInfertility in resource-constrained settings: moving towards ameliorationReprod Biomed Online20132618919523260034

- OmbeletWCookeIDyerSSerourGDevroeyPInfertility and the provision of infertility medical services in developing countriesHum Reprod Update200814660562118820005

- SharmaSMittalSAggarwalPManagement of infertility in low resource countriesBJOG2009116Suppl 1778319740177

- WHOGlobal and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual ViolenceGenevaThe World Health Organization2013

- WHOResponding to Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence Against Women: WHO Clinical and Policy GuidelinesGenevaThe World Health Organization2013

- ICMInternational code of ethics for midwivesAdopted at 2008 Glasgow Council Meeting2008 Reviewed and adopted at the Prague Council Meeting; 2014 Available from: http://www.internationalmidwives.orgAccessed December 30, 2015

- ICMThe role of the midwife in researchAdopted at 2008 Glasgow Council Meeting2008 Reviewed and adopted at the Prague Council Meeting; 2014 Available from: http://www.internationalmidwives.org/ Position StatementAccessed December 30, 2015

- Chief Nursing Officers of England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and WalesMidwifery 2020: delivering expectationsCambridgeJill Rogers Associates2010 Available from: http://www.midwifery2020.orgAccessed December 30, 2015

- GebbieKRosenstockLHernandezLMWho Will Keep the Public Healthy? Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st CenturyWashington DCNational Academy of Sciences2003 Available from: http://www.nap.eduAccessed December 31, 2015

- ICMEssential competencies for basic midwifery practice 2010 Revised 2013International Confederation of Midwives2013 Available from: http://www.internationalmidwives.orgAccessed December 31, 2015

- CSDHClosing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of HealthGenevaWorld Health Organization2008

- Mangham-JefferiesLMathewosBRussellJBekeleAHow do health extension workers in Ethiopia allocate their time?Hum Resour Health20141261 Available from: http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/12/1/61Accessed May 12, 201625315425

- KarimAMAdmassuKSchellenbergJEffect of Ethiopia’s health extension program on maternal and newborn health care practices in 101 rural districts: a dose-response studyPLoS One201386e6516023750240

- ICMThe International Confederation of Midwives Dissemination Pack. Global standards, competencies and toolsThe International Confederation of Midwives2014 Available from: http://www.internationalmidwives.org/assets/uploads/documents/Dissemination/140508%20Dissemination%20ICM%20V06.pdfAccessed on May 12, 2016

- WHOThe World Health Report 2006GenevaWorld Health Organization2006

- UNAIDS2015 Progress Report on the Global Plan Towards the Elimination of New HIV Infections Among Children and Keeping their Mothers AlivesGenevaJoint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS2015

- NelissenEErsdalHMdumaEHelping mothers survive bleeding after birth: retention of knowledge, skills, and confidence nine months after obstetric simulation-based trainingBMC Pregnancy Childbirth20151519026303614

- EvansCLJohnsonPBazantEBhatnagarNZgamboJKhamisARCompetency-based training “helping mothers survive: bleeding after birth” for providers from central and remote facilities in three countriesInt J Gynaecol Obstet2014126328629024834851

- DresangLTGonzálezMMBeasleyJThe impact of advanced life support in obstetrics (ALSO) training in low-resource countriesInt J Gynaecol Obstet2015131220921526294169

- Klingberg-AllvinMCleeveAAtuhairweSComparison of treatment of incomplete abortion with misoprostol by physicians and midwives at district level in Uganda: a randomized controlled equivalence trialLancet20153852392239825817472

- BarnardSKimCParkMHNgoTDDoctors or mi-level providers for abortionCochrane Database Syst Rev20157CD01124226214844

- WarrinerIKMeirikOHoffmanMRates of complication in first-trimester manual vacuum aspiration abortion done by doctors and mid-level providers in South Africa and Vietnam: a randomised controlled equivalence trialLancet20063681965197217141703

- WarrinerIKWangDHuongNTCan midlevel health-care providers administer early medical abortion as safely and effectively as doctors? A randomised controlled equivalence trial in NepalLancet20113771155116121458058

- BlumenthalPLauterbachMSellorsJSankaranarayananRTraining for cervical cancer prevention programs in low-resource settings: Focus on visual inspection with acetic acid and cryotherapyInt J Gynaecol Obstet2005892S30S3715823264

- PoliURBidingerPDGowrishankarSVisual Inspection with Acetic Acid (VIA) screening program: 7 years experience in early detection of cervical cancer and pre-cancers in rural South IndiaIndian J Community Med201540320320726170547

- BluestoneJJohnsonPFullertonJCarrCAldermanJBonTempoJEffective in-service training design and delivery: evidence from an integrative literature reviewHum Resour Health2013115124083659

- AERAStandards for Educational and Psychological TestingAmerican Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education2014

- NCSBNReport of Findings from the 2011 RN Nursing Knowledge SurveyChicago, ILNational Council of State Boards of Nursing2012