Abstract

A debate among gynecologic and reproductive surgeons is whether or not there is a clinical need to treat all intramural myomas. Considerations include myoma size and number, ability to access them, whether or not they compromise the endometrium, and treatment effect on gynecologic, reproductive, and obstetric outcomes. We conducted a detailed study regarding intramural myomas, their prevalence in subject populations, the imaging methods used to detect them, their growth rate, their suspected adverse effects on gynecologic, fertility, and obstetric outcomes, and the effectiveness of various treatment methods. The growing body of evidence reported in the literature supports the need to manage intramural myomas and to treat them appropriately.

Overview of uterine myomas

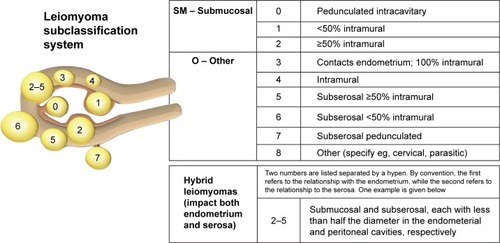

Uterine myomas have been classified according to their general uterine position: submucous, intramural, and subserosal. Munro et alCitation1 further classified myomas into nine types according to the degree of intracavitary and serosal distortion. Although the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics classification has allowed the researchers, imaging specialists, and surgeons specificity when identifying and treating myomas, the older classification (submucous, intramural, and subserosal) persists in the literature. The focus of our research is intramural myomas, primarily the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics types 3 and 4 ().

Figure 1 FIGO leiomyoma subclassification system.

Abbreviation: FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Depending on the number, sizes, and types of myomas, the age of the patient, her desire for uterine conservation, her workplace, personal environment, and lifestyle, and her presenting symptoms, treatment can take any of several medical and surgical courses.Citation2 Treatment goals are long-term reduction in myoma volume and reduction or elimination of symptoms with minimal side effects. Although medical therapies have been used to reduce bleeding and/or myoma volume, they are not without limitations and side effects, and medical therapies are often followed by surgical or interventional management. The decision to manage treatment by surgical or interventional means must take into account myoma size and number, proximity to the endometrium, ability to access and treat them, potential adverse consequences, as well as patient preference. Pretreatment assessment by ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as well as evaluation of comorbidities may also preclude a patient from undergoing certain procedures.

Intramural myomas

Intramural myomas are the most prevalent of all the leiomyomas. Two-dimensional transvaginal sonography detected a 58%–79% occurrence of intramural myomas among study populations with observable myomas.Citation3,Citation4 MRI and laparoscopic ultrasound (LUS) are also used for myoma detection. In a multicenter retrospective study involving two-dimensional transvaginal sonography, MRI, and LUS, intramural myomas comprised 58% of all myomas imaged, regardless of the imaging method used.Citation3

Myomas have a median growth rate of 35.2% by volume per year, and small (<2 cm) myomas grow significantly faster than do larger ones.Citation5,Citation6 Mavrelos et alCitation5 detected a higher yearly volumetric increase of intramural myomas (53.2%) compared to either subserosal or submucous myomas: 25.1% and 22.8%, respectively. The literature provides conflicting or inadequately designed studies of the negative effects of intramurals.Citation7–Citation16 The heterogeneous nature of intramural myomas (in terms of their relationship to the endometrial cavity, their size, and whether they occur as single or multiple tumors) and the conflicting diagnoses of what constitutes an intramural myoma illustrate the difficulty of the research.

In a prospective trial, Yoshino et alCitation7 studied the increased frequency of uterine peristalsis in a group of infertile women who had intramural myomas, but no submucous myomas and no other infertility factors. The authors separated the women into two groups: one exhibiting low-frequency peristalsis (<2 times/3 minutes) during the midluteal phase and the other exhibiting higher-frequency peristalsis (≥2 times/3 minutes). There were no significant differences in the two groups in terms of presence of endometriosis, distortion of the endometrial cavity, and number and size of intramural myomas. Less than half of the study subjects exhibited high-frequency peristalsis, none of whom achieved pregnancy, whereas 34% of the low-frequency group achieved pregnancy (P<0.005). The authors suggest that abnormal uterine peristalsis in the presence of intramural fibroids may compromise pregnancy rates. Yan et alCitation8 retrospectively investigated the effect that intramural myomas not distorting the endometrial cavity have on the outcome of in vitro fertilization treatment. Although such myomas did not affect in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcomes, intramural myomas >2.85 cm significantly compromised live birth rate (P=0.043).

Another prospective study was undertaken to analyze the effects of the distance between small (≤4 cm) intramural uterine myomas and the endometrium on the outcomes of embryo transfer.Citation9 The two groups of study subjects comprised infertile women with small intramural myomas (n=117) and a control group of infertile women without uterine myomas (n=117). Outcomes were studied for distances from ≤1 to >3 mm, with no myomas contacting or distorting the endometrium. The implantation rate (31.91%) and live birth rate (33.33%) were significantly lower and the spontaneous miscarriage rate (20.37%) was significantly higher for the myoma group than for the control group (45.67%, 52.14%, and 7.35%, respectively) (all, P<0.05).

In addition, histology and biochemical activity of individual myomas and their effects on the endometrium need continued in-depth study.Citation10 Tinelli et alCitation11 reported on their analysis of uterine myoma pseudocapsule thickness and histology based on earlier findings by Wei et alCitation12 that the most biologically active area of a myoma is its pseudocapsule. Tinelli et alCitation13 found that intramural myomas near the endometrial cavity were considerably thicker with physiologically active neuropeptides and neurotransmitters. The authors suggested that uterine myomas might best be managed based on immunohistochemical studies of myoma pseudocapsules.

Some authors have expressed reluctance to support treatment of intramural myomas in subfertile women. Cited reasons include lack of sufficient evidence and poorly designed trials, insufficient studies supporting or refuting the clinical benefits of treatment of non–cavity-distorting intramural myomas, and the inherent surgical complications and required expertise in the treatment of intramural myomas.Citation14–Citation17

Uterine-conserving therapies for the treatment of intramural myomas

Myomectomy

Myomectomy has been the mainstay treatment of symptomatic leiomyomas in women seeking uterine-conserving therapy and conservation and improvement in reproductive outcomes. Depending on the target myomas and the surgeon’s preference and expertise, myomectomy approaches include hysteroscopic, laparoscopic, robotic-assisted laparoscopic, and laparotomic, the latter involving direct palpation of the uterus. Hysteroscopic myomectomy is reserved for treatment of submucous types 0, 1, and 2 myomas – the latter excised only if <4 cm in greatest diameter and only by surgeons with advanced hysteroscopic technique and experience.Citation16 Intramural myomas are more readily treated at laparotomy through a low transverse incisionCitation14 or at conventional laparoscopy or robotic-assisted laparoscopy. Careful palpation helps the surgeon to target hard-to-reach intramural fibroids during the open procedure.Citation14 However, palpation of the uterus has limitations. In a prospective study evaluating LUS, surgeons performed the laparotomic procedure on women diagnosed preoperatively with symptomatic myomas (68.2% of which were intramural, 29.6% were subserosal, and 2.2% were submucous) and palpated the uterus to target the benign tumors.Citation18 After excision of what they thought were all of the myomas, the surgeons incorporated LUS into each procedure to determine how many myomas, if any, were left. LUS permitted the detection of 46 residual myomas, 95.66% of which were intramural and 4.34% were submucous.

In a retrospective study of 145 consecutive cases, HanafiCitation19 evaluated those factors that were associated with recurrence of myomas that were at least 2 cm in greatest diameter and that formed after open myomectomy. At surgery, 68% of the patients had intramural or intramural–subserosal myomas, 4% had submucous or submucous–intramural myomas, 23% had subserosal myomas, and 5% had myomas in all locations. He reported that the cumulative probability of myoma recurrence increased after surgery to 62% at 5 years and was significantly greater in those women with ≥2 myomas and in those women with a uterine size of >10 gestational weeks. Of the group of patients with reported recurrence, 52% underwent subsequent surgical intervention. One of the limitations of the study was the lack of reporting on the locations of the myomas detected at follow-up.

Radosa et alCitation20 also reported on myoma recurrence rate after laparoscopic myomectomy. Of the 443 myomas removed, 155 (35%) were intramural, 177 (40%) were subserosal, and 111 (25%) were pedunculated. Of the 331 women who were initially studied, 107 were lost to follow-up and 224 were followed postoperatively to 108.23±24.41 months. The recurrence rate at 60 months for intramural/subserous (FIGO type 2–6, ) myomas was 23.04%. Two factors significantly increased the risk for recurrence of symptoms: age between 30 and 40 years and presence of multiple myomas at surgery. Increased risk of recurrence may also have been due to the surgeons not excising all myomas that were present at baseline. For example, in a randomized trial, Brucker et alCitation21 reported excision of only 80.3% of myomas imaged on LUS, leaving in place intramural myomas that were located deep in the myometrium.

Uterine artery embolization

Uterine artery embolization (UAE) is an established minimally invasive, percutaneous, image-guided interventional technique involving the occlusion of one or both uterine arteries supplying blood to target myomas, including intramurals and intramurals abutting the endometrium, but not pedunculated myomas. Three studies of UAE indicated that the procedure is compromised by high rates of postprocedural complications and high rates (28%–32%) of reintervention – including re-embolization, myomectomy, or hysterectomy – at 5 years postprocedure.Citation22–Citation24 Failure, defined as reintervention, after UAE appears to occur within the first 4 years of the procedure and reflects insufficient infarction.Citation25,Citation26 However, UAE provides a safe alternative to more surgically invasive procedures, such as myomectomy, in women who are poor surgical candidates, have fewer than six myomas, and do not desire future childbearing.Citation27

Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound

Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) describes an approved device (Exablate; Insightec, Tirat Carmel, Israel) and method for noninvasive, nonsurgical ablation of leiomyomas, including intramurals, by focused ultrasound waves, which are guided to the target tissue by real-time three-dimensional MRI. Limitations of MRgFUS include the exclusion of women of large (>115 kg) habitus, the presence of bowel obstructing the target myoma, large fibroid volume (uterine size >24 weeks), and presence of intracavitary, nonenhancing, or heavily calcified myomas.Citation28–Citation30 The treatment is also contraindicated in women with abdominal scarring, metal implants, or claustrophobia. Froeling et alCitation31 determined a 30% reintervention rate for MRgFUS after a median follow-up period of 13.3 months. Given the contraindications and costs, MRgFUS is an option to a limited subset of symptomatic patients.

Radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation

Radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation (RFVTA: the Acessa procedure; Halt Medical, Inc., Brentwood, CA, USA) is an outpatient, uterine-sparing, LUS-guided myoma ablation treatment that requires no myometrial or serosal suturing. LUS guides the surgeon’s targeting and treatment of each myoma, regardless of its size or location within the uterus. Because laparoscopic and ultrasound visualization guides the treatment, even small (<1 cm) and otherwise hard-to-access intramural myomas can be ablated.

In a pivotal trial analyzing the reduction in menstrual blood loss in women with moderate-to-severe heavy menstrual bleeding (from ≥160 to ≤500 mL as assessed by alkaline hematin) and who were treated with RFVTA, gynecologic surgeons treated 640 myomas.Citation32 Calcified myomas and myomas that measured 0.7–9.7 cm in largest diameter were included, and the number of myomas treated per study participant ranged 1–29. Of the 135 study subjects, only 48.4% had one or more submucous myomas in addition to myomas in other locations; yet, 135 women suffered from heavy menstrual bleeding. Of the 124 subjects followed to 12 months, a subset of 63 subjects had intramural myomas but no submucous myomas. This group greatly outnumbered the converse subset, that is, those with submucous myomas but no intramurals (n=10). The intramural group showed statistically and clinically significant reduction in menstrual blood loss: −31.8% (95% confidence interval, −41.4% to −22.2%; P<0.001) after ablation of their myomas.Citation32–Citation34 The cumulative reintervention rate at 3 years of follow-up post-RFVTA was 11%.Citation35 RFVTA has not been cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration for the indication of infertility due to myomas or in women who desire future pregnancy.

Conclusion

The growing body of evidence reported in the literature supports the need to diagnose intramural myomas and manage them, in order to reduce the recurrence of symptoms and the need for further intervention. Rigorous prospective research should be undertaken to define clearly the negative influence that intramural myomas have on patients’ well-being. Patients with symptomatic intramural myomas should be carefully evaluated and appropriately treated.

Acknowledgments

The authors received third-party editorial support, which was funded by Halt Medical, Inc.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- MunroMGCritchleyHOBroderMSFraserISFIGO Working Group on Menstrual DisordersFIGO classification system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive ageInt J Gynaecol Obstet2011113131321345435

- LeeBBIsaacsonKBDiamondMPRadiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation of symptomatic uterine fibroids: the Acessa procedureAl-HendyASalamaSEtiology, Clinical Manifestations, Evaluation and Management of Uterine LeiomyomaNew YorkNova Science2015175193

- LevineDJBermanJMHarrisMChudnoffSGWhaleyFSPalmerSLSensitivity of myoma imaging using laparoscopic ultrasound compared with magnetic resonance imaging and transvaginal ultrasoundJ Minim Invasive Gynecol201320677077424021910

- MosheshMPeddadaSDCooperTBairdDIntraobserver variability in fibroid size measurementsJ Ultrasound Med2014331217122424958408

- MavrelosDBen-NagiJHollandTHooWNaftalinJJurkovicDThe natural history of fibroidsUltrasound Obstet Gynecol20103523824120069541

- BairdDDGarrettTALaughlinSKDavisBSemelkaRCPeddadaSDShort-term change in growth of uterine leiomyoma: tumor growth spurtsFertil Steril201195124224621168581

- YoshinoOHayashiTOsugaYDecreased pregnancy rate is linked to abnormal uterine peristalsis caused by intramural fibroidsHum Reprod201025102475247920719814

- YanLDingLLiCWangYTangRChenZJEffect of fibroids not distorting the endometrial cavity on the outcome of in vitro fertilization treatment: a retrospective cohort studyFertil Steril2014101371672124424367

- LuNWangYSuYCSunYPGuoYHEffects of the distance between small intramural uterine fibroids and the endometrium on the pregnancy outcomes of in vitro fertilization-embryo transferGynecol Obstet Invest2015791626825427667

- OliveDLThe surgical treatment of fibroids for infertilitySemin Reprod Med201129211312321437825

- TinelliAMynbaevOAMettlerLA combined ultrasound and histologic approach for analysis of uterine fibroid pseudocapsule thicknessReprod Sci20142191177118624879045

- WeiJJZhangXMChiribogaLYeeHPerleMAMittalKSpatial differences in biologic activity of large uterine leiomyomataFertil Steril200685117918716412751

- TinelliAMalvasiACavallottiCThe management of fibroids based on immunohistochemical studies of their pseudocapsulesExpert Opin Ther Targets201115111241124721961807

- FalconeTParkerWHSurgical management of leiomyomas for fertility or uterine preservationObstet Gynecol2013121485686823635687

- MetwallyMCheongYCHorneAWSurgical treatment of fibroids for subfertilityCochrane Database Syst Rev201214;11CD003857

- PrittsEAParkerWHOliveDLFibroids and infertility: an updated systematic review of the evidenceFertil Steril20099141215122318339376

- Carranza-MamaneBHavelockJHemmingsRThe management of uterine fibroids in women with otherwise unexplained infertilityJ Obstet Gynaecol Can201537327728826001875

- AngioliRBattistaCTerranovaCIntraoperative contact ultrasonography during open myomectomy for uterine fibroidsFertil Steril20109441487149019962141

- HanafiMPredictors of leiomyoma recurrence after myomectomyObstet Gynecol2005105487788115802421

- RadosaMPOwsianowskiZMothesALong-term risk of fibroid recurrence after laparoscopic myomectomyEur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol2014180353925016181

- BruckerSYHahnMKraemerDTaranFAIsaacsonKBKrämerBLaparoscopic radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation of fibroids versus laparoscopic myomectomyInt J Gynaecol Obstet2014125326126524698202

- WatkinsonANicholsonAUterine artery embolization to treat symptomatic uterine fibroidsBMJ2007335762272072217916857

- MossJGCooperKGKhaundARandomised comparison of uterine artery embolisation (UAE) with surgical treatment in patients with symptomatic uterine fibroids (REST trial): 5-year resultsBJOG2011118893694421481151

- van der KooijSMBipatSHehenkampWJAnkumWMReekersJAUterine artery embolization versus surgery in the treatment of symptomatic fibroids: a systematic review and metaanalysisAm J Obstet Gynecol20112054317.e1e1821641570

- Scheurig-MuenklerCKoestersCPowerskiMJGrieserCFroelingVKroenckeTJClinical long-term outcome after uterine artery embolization: sustained symptom control and improvement of quality of lifeJ Vasc Interv Radiol201324676577123582992

- KatsumoriTKasaharaTKinYNozakiTInfarction of uterine fibroids after embolization: relationship between postprocedural enhanced MRI findings and long-term clinical outcomesCardiovasc Intervent Radiol201131667217943351

- MaraMKubinovaKEmbolization of uterine fibroids from the point of view of the gynecologist: pros and consInt J Womens Health2014662362925018653

- ClarkNAMumfordSLSegarsJHReproductive impact of MRI-guided focused ultrasound surgery for fibroids: a systematic review of the evidenceCurr Opin Obstet Gynecol201426315116124751998

- FrölingVKrönckeTJSchreiterNFTechnical eligibility for treatment of magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgeryCardiovasc Intervent Radiol201437244545023839005

- BeheraMALeongMJohnsonLBrownHEligibility and accessibility of magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) for the treatment of uterine leiomyomasFertil Steril20109451864186819931074

- FroelingVMeckelburgKScheurig-MuenklerCMidterm results after uterine artery embolization versus MR-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound treatment for symptomatic uterine fibroidsCardiovasc Intervent Radiol20133661508151323456309

- ChudnoffSGBermanJMLevineDJHarrisMGuidoRSBanksEOutpatient procedure for the treatment and relief of symptomatic uterine myomasObstet Gynecol20131211075108223635746

- GalenDIIsaacsonKBLeeBBDoes menstrual bleeding decrease after ablation of intramural myomas? A retrospective studyJ Minim Invasive Gynecol201320683083524018147

- LukesASMuseKRichterHEMooreKAPatrickDLEstimating meaningful reduction in menstrual blood loss for women with heavy menstrual bleedingCurr Med Res Opin2010262673267820942615

- BermanJMGuidoRSGarza LealJGPemuellerRRWhaleyFSChudnoffSGHalt Study GroupThree-year outcome of the Halt trial: a prospective analysis of radiofrequency volumetric thermal ablation of myomasJ Minim Invasive Gynecol201421576777424613404