Abstract

The physiological decrease in vaginal estrogens is accountable for the emergence of vulvar and vaginal atrophy (VVA) and its related symptoms such as vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, vaginal and/or vulvar irritation or itching, and dysuria. The repercussion of these symptoms on quality of life often makes it necessary to initiate treatment. Up until now, the treatments available included vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, local estrogens, and hormonal therapy. However, therapeutic options have now been increased with the approval of 60 mg ospemifene, the first nonhormonal oral treatment with an agonist effect on the vaginal epithelium and an endometrial and breast safety profile which makes it unique. This is the first selective estrogen receptor modulator indicated in women with moderate-to-severe vaginal atrophy not eligible for local estrogen treatment. Considering that “local estrogen noneligible women” are those in whom such treatment cannot be administered either because it is contraindicated or due to skill issues, who are averse to the mode and convenience of vaginal products’ administration or to their use on account of potential systemic absorption, or those who demonstrate dissatisfaction in terms of efficacy and safety, it is clear that there is a significant unmet medical need in VVA management. In fact, a great number of women show lack of adherence, dropping out of at least one VVA treatment, including nonhormonal moisturizers and lubricants, which they consider to be ineffective and uncomfortable. If they could choose, many of them may opt for oral treatment. In Phase III studies, ospemifene demonstrated efficacy in vaginal dryness and dyspareunia, regenerating vaginal cells, improving lubrication, and reducing pain during sexual intercourse. Symptoms improved in the first 4 weeks and endured for up to 1 year. Additionally, it demonstrated a good endometrial, cardiovascular system, and breast safety profile.

Introduction

The physiological decrease of vaginal estrogens modifies the characteristics of the vaginal epithelium, which becomes squamous and stratified, whereas it was wet and wrinkled before menopause.Citation1 Under hypoestrogenism conditions, the vaginal epithelium becomes thinner, vaginal elasticity decreases, connective tissue increases, and vaginal blood flow is reduced. The decrease in surface epithelial cells below 5% means lower cell exfoliation, lower glycogen release, and lower hydrolysis to glucose, which causes reduced lactobacillus-induced transformation to lactic acid and increased vaginal pH over 4.5.Citation1 The alkaline environment encourages a change in bacterial microbiota, which implies a risk of dysbiosis.Citation1 In addition, vaginal stenosis and risk of damage as a result of vaginal elasticity loss, as well as lubrication reduction owing to lower blood inflow, can bring about some of the typical symptoms of vulvar and vaginal atrophy (VVA), such as vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, vaginal and/or vulvar irritation or itching, dysuria, and vaginal bleeding associated with sexual intercourse.Citation1

A new terminology has been proposed to refer to vulvovaginal atrophy or atrophic vaginitis: genitourinary syndrome of menopause. It is considered that the two terms that have been used so far, vulvovaginal atrophy and atrophic vaginitis, do not include the variety of signs and symptoms that occur during this time; especially, they do not include the ones related to urinary tract symptoms (dysuria, nocturia, etc). It has also been seen that not all people are comfortable talking about the vulva and/or vagina and the term atrophy may have a derogatory connotation.Citation2

Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause (GSM) or VVA diagnosis is clinical, and apart from symptoms, it is supported by the visual examination of clinical signs such as pallor, redness, petechiae, dryness, and friability of the genital mucosa. Other parameters supporting diagnosis and helping differential diagnosis to be carried out include vaginal pH and vaginal maturation index (MI). Given that the epithelial covering of the vaginal wall is extremely estrogen-sensitive, the cell proportion in the superficial, intermediate/superficial spinous, and spinous/parabasal cell strata is suggestive of estrogen stimulation and is used to assess the estrogenization degree of the vaginal epithelium.Citation3 Vaginal MI is reduced in postmenopausal women owing to the decrease in superficial cells below 5%. Nevertheless, these laboratory data or clinical signs at visual examination are not necessarily correlated with VVA symptoms.Citation3 The same applies to the clinical signs of estrogen deficiency in the vaginal tissue, which are not always associated with severe or persistent vaginal symptoms in all women either.Citation4 A clear example of this is Gass et al’s work,Citation5 where only 10% of the patient population with clear signs of VVA at physical exploration reported moderate-to-severe vaginal dryness. This suggests that there are certain contextual and behavioral factors which can have a more significant impact on women’s subjective experience about their own symptoms than purely physical signs of atrophy or inflammation.Citation6

The prevalence and impact of vulvar and vaginal symptoms on postmenopausal women’s quality of life often makes it necessary to initiate treatment. This review analyzes the clinical data available with ospemifene, the first selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) indicated in women with VVA. For that purpose, a limited literature search was conducted on key resources, including PubMed, the Cochrane Library, Corporate Receivables Inc - Collection Agency, and major international health technology agencies. Filters were applied to specific questions related to ospemifene, VVA, and dyspareunia. The search was also limited to English language.

Treatment options

Hormone therapy (HT)

For decades, HT with estrogens either in monotherapy or combined with progestogens has been the treatment of choice for menopausal symptoms’ relief and osteoporosis prevention.Citation7 HERSCitation8 and WHICitation9 study findings changed the previous perception of HT’s risk–benefit as they showed an increased risk of cardiovascular disease,Citation8,Citation9 thromboembolism, and invasive breast cancer associated with estrogens. Since then, HT is no longer recommended for chronic disease prevention,Citation7,Citation10 not even in breast cancer patients.Citation7,Citation9,Citation11,Citation12 However, there is evidence supporting a different approach to HT management of menopausal symptoms by employing the lowest possible dose and individualizing treatment based on patient age and symptom severity. Currently, systemic HT is not indicated in patients with VVA as their only menopausal symptom.Citation13

Local estrogen therapy

For VVA cases with no menopausal symptoms other than hot flashes, local estrogen therapy is recommended.Citation14 Apart from preventing systemic hormone therapy side-effects, it is probably more effective in relieving vulvar and vaginal symptoms and improving cytological results,Citation15 whether used in creams, rings, ovules, or tablets.Citation16 Local estrogens are highly effective in reverting physiological changes associated with VVA; they foster vaginal cell growth and maturation, favor lactobacillus recolonization, improve blood flow, lower pH, increase vaginal epithelium thickness and elasticity, and enhance sexual function.Citation15,Citation17,Citation18 There is evidence that the effects of these intravaginal preparations are not limited to the vaginaCitation13,Citation19 and that there is a risk of systemic absorption due to the vaginal atrophic state, especially during the first days of treatment.Citation13,Citation18,Citation19 However, an increase in plasma estrogen levels with ultralow doses of local estrogen therapy has not been demonstrated;Citation20 therefore, it is not necessary to add a progestogen to establish controls to asses endometrial stimulus.Citation21,Citation22 As the epithelium matures as a result of treatment, absorption decreases and small estrogen doses are required to prevent recurrent atrophy.Citation23

To meet treatment goals, it is recommended to apply the lowest local estrogen dose possible over the shortest time possible.Citation18,Citation21,Citation22 A low dose below 50 mcg per application is expectedCitation21,Citation22 to induce as few systemic effects as possible and maintain plasma estrogen levels within the normal postmenopausal range.Citation21,Citation22 Concerns about a potential systemic absorption of intravaginal estrogens and their stimulating effects on the breast and the endometrium, among other adverse events (AEs), can prevent long-time use.Citation19,Citation24 Indeed, 12%–38% of local estrogen-treated REVIVE survey respondentsCitation21 and 33% of VIVA survey respondentsCitation25 admitted that they were concerned about hormone exposure, and 30% of VIVA respondentsCitation25 were reluctant to use local estrogen therapy. As a matter of fact, safety was the element women were more dissatisfied with (40%), followed by efficacy (25%).

Vaginal moisturizers and lubricants

Local estrogen administration may be contraindicated in women with undiagnosed uterine/vaginal bleeding, or with a previous history of hormone-dependent tumors such as breast, ovary or endometrial cancer and cervical adenocarcinoma.Citation21,Citation26 It can also prove uncomfortable in women with skill problems (for instance, arthritis, obesity or stroke). In such cases, and also in women who wish to avoid hormone treatment, guidelines recommend vaginal moisturizers or lubricants as first-line treatment.Citation13,Citation16,Citation21,Citation27 In addition, the use of vaginal moisturizers or lubricants to relieve dryness symptoms in women not responding to estrogens should also be considered.Citation13 These products do not treat the underlying condition,Citation13 but do provide temporary relief of vaginal atrophy symptoms,Citation28 such as dryness and pain during sexual intercourseCitation13 with lubricant use. Moisturizers’ benefits may last longer if used continuously,Citation13,Citation29 but their efficacy in vaginal symptoms is lower as compared to local estrogens,Citation28 and less than 50% of postmenopausal women in Europe are satisfied with their moisturizer or lubricant. Use is sometimes associated with vaginal irritation,Citation13 contact dermatitis, and allergy.Citation30

Other natural products for vaginal health include phytoestrogens, which are nonsteroidal vegetal compounds with estrogen receptor (ER) binding capacity. Some studies suggest beneficial effects on the urogenital sphereCitation31,Citation32 as they improve symptoms of dyspareunia, vaginal dryness, and maturation value.Citation33 Given their estrogen agonist effects and the lack of safety data in women with estrogen-sensitive tumors, phytoestrogens should be recommended cautiously.Citation13

SERMs

SERMs are a heterogeneous group made up of nonsteroidal compounds mostly which act as estrogen receptor (ER) ligands but were developed as targeted therapies.Citation34 In other words, contrary to estrogens, which usually have an agonist activity, SERMs exert a mixed agonist or antagonist action depending on the target tissue.Citation35–Citation38 This represents a pharmacological advantage as it prevents AEs in nontarget tissues.Citation39 SERMs’ tissue-specific activity is partly determined by a differential and specific affinity for ER α or β subtypes, with a differential tissue expression pattern each, and by the formation of ligand-receptor complexes with differential effects on gene regulation depending on ERα or ERβ binding.Citation40,Citation41

The importance of ER-mediated signaling in normal tissues shows the therapeutic potential of selective ER binding in the management of postmenopausal disorders associated with estrogen deficiency, such as osteoporosis.Citation42 This is one of the main clinical applications of SERMs in postmenopausal women, along with the maintenance of a beneficial serum lipid profileCitation39 and oncologic treatment.Citation43 However, potentially severe adverse reactions (ARs) such as thromboembolic events and uterine cancer complicate their long-term use required both for osteoporosis prevention and breast cancer prevention and treatment.Citation39,Citation44 The idea of an ideal SERM, would be one that acts as an agonist agent in the bone, brain, and cardiovascular system, and as a neutral or antagonist agent in the endometrium and breast.Citation42 But for now, each SERM must be considered individually and depending on their specific therapeutic indication. An example of that is tamoxifen, the first SERM used in clinical practice and the most effective agent in ER-positive breast cancer treatment owing to its breast antiestrogenic activity. Nevertheless, its agonist effect in the uterus and its endometrial hyperplasia-associated risk limits its use to breast cancer postmenopausal population,Citation42 thus being ruled out as a potential treatment for postmenopausal osteoporosis, since risks are more important than bone protection benefits.Citation44 Raloxifene is a SERM with antagonist estrogen effect in the breast and a neutral one in the uterus which has demonstrated endometrial safety, efficacy in bone fracture and bone loss prevention, and an added benefit in breast cancer prevention,Citation44 but which induces or exacerbates hot flashes.Citation45 Other SERMs currently used in clinical practice include clomiphene, approved in the US for ovulatory dysfunction treatment in women desiring to get pregnant,Citation40 toremifene in postmenopausal women with metastatic hormone dependent breast cancer,Citation46 and bazedoxifene for osteoporosis treatment in women with increased fracture risk.Citation47

Selectively targeted SERMs against VVA’s underlying physiopathology could be an alternative to local estrogen or systemic hormone therapy in the management of VVA symptoms in women with a previous history of breast cancer or currently with breast cancer, or simply in women who prefer to avoid such treatments. However, tamoxifen, raloxifene, and bazedoxifene as monotherapy are not currently indicated in VVA treatment.Citation48–Citation52 Briefly, tamoxifen has demonstrated an agonist and antagonist activity in the vaginal epithelium,Citation53 as well as gynecological adverse effects such as dyspareunia and vaginal dryness.Citation50,Citation52 The evidence available for raloxifene does not show any effect on postmenopausal monotherapy-treated women’s urogenital epithelium,Citation48,Citation50 or in combination with vaginal estrogens as it provides no additional benefit in relieving genitourinary atrophy signs and symptoms.Citation53–Citation55 Data on bazedoxifene, although limited, conclude that it could only be a safe and effective option in combination with conjugated estrogens as it improves VVA measuresCitation56,Citation57 and reduces the incidence of dyspareunia, among other moderate-to-severe VVA symptoms.Citation58

Among marketed SERMs, only ospemifene (a toremifene derivative) has an estrogenic agonist activity on the vaginal epithelium already noted in the first nonclinical studiesCitation59 and Phase I, II and III studies.Citation60 This singular tissue selectiveness seems to be molecular structure-related.Citation61 It is the first non-hormonal selective modulator with multiple tissue-specific actions and, contrary to other SERMs, with an antagonist function in endometrial and breast tissue.Citation59,Citation62,Citation63

Ospemifene

Clinical development

Ospemifene’s clinical development included 21 Phase I studies and nine Phase II/III studies, as well as a population pharmacokinetics analysis and 12 nonclinical in vitro studies with human samples.Citation64 In the Phase II/III studies, a total of 1,892 postmenopausal women, with and without uterus, were given at least one dose of ospemifene, approximately 80% of whom received a dose ≥60 mg daily.Citation64 Seventy-two percent of patients were treated for at least 12 weeks, 35% for at least 6 months, and 22% for at least 1 year, with a maximum exposure of 89 weeks.Citation64

Phase III studies

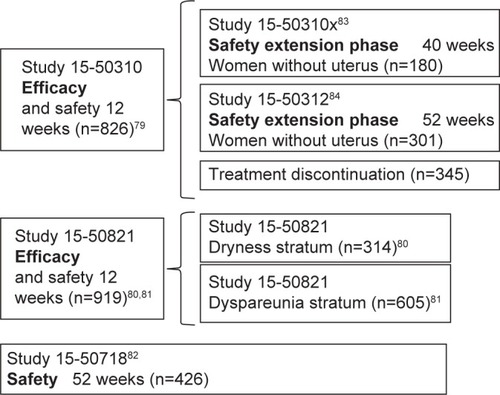

Aside from the 12-week Phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (Study 717)Citation64 to assess ospemifene’s minimum effective dose (5 mg/15 mg/30 mg), clinical efficacy in symptomatic VVA treatment in postmenopausal women was primarily determined in three Phase III multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies: two 12-week reference studies (Studies 310 and 821)Citation65–Citation67 and one 52-week safety study (Study 718)Citation68 (). Once the ospemifene initial reference study’s (Study 310)Citation65 double-blind phase was completed, patients with an intact uterus could voluntarily choose to undergo an open-label extension phase with 60 mg ospemifene for up to 40 weeks (Study 31x),Citation69 and hysterectomized patients could choose to undergo an open-label extension phase for up to 52 weeks (Study 312)Citation70 in order to assess long-term safety. This led to the approval of oral ospemifene (60 mg/day) as the first nonhormonal SERM for moderate-to-severe dyspareunia treatment in VVA postmenopausal women.Citation71

Both 12-week reference studies included postmenopausal women aged 40–80 years with the following VVA criteria: ≤5% of superficial cells at vaginal smear, vaginal pH >5.0, at least one moderate or severe VVA symptom (Study 310),Citation65 or moderate-to-severe vaginal dryness or sexual activity associated dyspareunia (Study 821).Citation66,Citation67 In the 52-week safety study (Study 718),Citation68 patients had to have an intact uterus, although they were not selected based on their VVA symptoms.

Primary endpoints of both 12-week reference studies included changes in parabasal and superficial cell percentage from baseline in the vaginal smear’s MI, changes in vaginal pH, and changes in severity of the most troublesome symptom (MTS), ranked on a 4-point scale (0: none; 1: mild; 2: moderate; 3: severe). Although safety was the 52-week Study 718’s primary goal,Citation68 data on 60 mg ospemifene efficacy at 12 weeks in objective measurements, superficial and parabasal cell percentage, and vaginal pH were also collected.

Secondary endpoints differed among studies. They included changes in VVA physiological markers at weeks 4 and 52 (Studies 310, 821, and 718)Citation65–Citation68 and MTS severity at week 4 (Studies 310 and 821),Citation65–Citation67 percentage of responding patients (Study 821),Citation66,Citation67 as well as lubricant use (Studies 310, 821)Citation65–Citation67 and sexual function at weeks 4 and 12 (Study 821).Citation66,Citation67 Patients with a MI 10-point increase, a vaginal pH 0.5 decrease, and a vaginal dryness severity 1-point reduction were considered as responding. Both in the 52-week safety study and in the 40- and 52-week extension phases of ospemifene’s initial reference study, changes observed at vaginal visual exploration regarding clinical signs of petechiae, pallor, friability, dryness, and mucosal redness – with their severity ranked on a 4-point scale (0: none; 1: mild; 2: moderate; 3: severe) – were analyzed.

Therapeutic efficacy

In the three Phase III studies, age, race, and body mass index demographic characteristics were comparable between both treatment arms, and discontinuation rates were low, with more than 80% of patients completing the 60 mg ospemifene 12- and 52-week treatment.

Effects on vaginal epithelium maturation and vaginal pH

After 4 weeks (Study 310),Citation65 and 12 weeks (Studies 310 and 821),Citation65–Citation67 60 mg ospemifene reduced the parabasal cell percentage (−30.1, −31.7, −40.3) and vaginal pH (−1.01, −0.95, −0.94) significantly, and increased superficial cell percentage (10.8, 7.0, 7.0) as compared to placebo (P<0.001). This significant changes were consistent among studies endured for 52 weeks in the long-term Study (718),Citation68 with a reduction of 40 in the percentage of parabasal cells and −1.22 of vaginal pH, and increased of 5 of the percentage of superficial cells (Study 718).Citation68

Effects on vaginal dryness and dyspareunia

In women reporting vaginal dryness and dyspareunia as the MTS in Study 310,Citation65 60 mg ospemifene reduced both symptoms’ severity significantly after 12 weeks of treatment as compared to placebo. Seventy-five percent of patients with vaginal dryness experienced improvement (≥1-point decrease in severity score), and 66%, relief (with no symptoms or mild symptoms). In the patient cohort who identified vaginal dryness as the MTS in Study 821, 60 mg ospemifene reduced the degree of severity reported from baseline significantly (−1.3) as compared to placebo (−1.1) (P=0.080),Citation66 and 46.3% of patients experienced substantial improvement (2-point or 3-point decrease in severity score) as compared to 34.4% treated with placebo (P<0.05).Citation72 In the patient cohort who identified dyspareunia as the MTS, 60 mg ospemifene also reduced the degree of severity significantly (−1.5) as compared to placebo (−1.2) (P<0.0001), and increased the percentage of patients who experienced improvement (80% vs 64% with placebo; P<0.001), substantial improvement (53% vs 39% with placebo; P<0.0001), or relief (63% vs 42.5% with placebo; P<0.0001).Citation67 Responding patient percentage was significantly higher in the 60 mg ospemifene arm as compared to the placebo arm (Study 310 [33.7% vs 3.4%; P<0.001], Study 821-dryness stratum [33.8% vs 7.1%; P<0.0001], Study 821-dyspareunia stratum [42.9% vs 4.6%; P<0.0001]).

Effects on VVA clinical signs

Ospemifene improved VVA clinical signs substantially both in hysterectomized womenCitation70 and in women with intact uterus.Citation69 Vaginal visual examination demonstrated actual improvements in vaginal dryness, redness, petechiae, pallor, and mucosal friability at weeks 12Citation73 and 26,Citation69,Citation70,Citation73 enduring for the whole 52-week 60 mg ospemifene treatment period as compared to placebo,Citation68–Citation70 with the majority of patients having no or mild VVA clinical signs at week 52.Citation68,Citation70

Effects on lubricant use and female sexual function

Ospemifene 60 mg clinical benefit was also demonstrated in lubricant use and sexual activity. In Studies 310 and 821,Citation65–Citation67 there was a trend toward lower lubricant use in the 60 mg ospemifene group vs placebo, with a slight reduction in the percentage of women reporting use following 3 weeks of treatment, and throughout the whole 12 weeks of the studies. Ospemifene 60 mg was also significantly more effective than placebo in terms of sexual activity improvement, measured through total Female Sexual Function Index score, in weeks 4 (5.29 vs 3.70; P<0.001) and 12 (6.69 vs 4.14; P<0.001). This improvement, which began to show up in the first 4 weeks of treatment with significant pain reduction during sexual intercourse (P<0.05 vs placebo) and higher lubrication (P<0.001 vs placebo), endured throughout the whole 12 weeks in the Female Sexual Function Index domains: arousal (P<0.05 vs placebo), desire (P<0.001 vs placebo), orgasm (P<0.001 vs placebo), lubrication (P<0.0001 vs placebo), satisfaction (P<0.05 vs placebo), and pain (P<0.0001 vs placebo).Citation74 These results were consistent both in hysterectomized women and women with intact uterus, and also in women with dyspareunia and vaginal dryness as the MTS.Citation74

Clinical application of efficacy data

Symptom improvement is a primary efficacy measurement based on ospemifene-treated women’s mean change in MTS severity, ranked on a 4-point scale (0: no symptom; 1: mild; 2: moderate; 3: severe).

All ospemifene results described previously demonstrate the treatment’s statistical significance. However, the clinical interpretation of data is essential not only for the physician, who may not be familiar with the use of numerical severity measurements within their clinical practice, but also for the patients to understand what they can actually expect from ospemifene treatment.

Nappi et alCitation72 analyzed the clinical relevance of Study 310 and Study 821 results,Citation65–Citation67 based on two concepts previously describedCitation75 (improvement and relief), and developing a new concept of “substantial improvement”.Citation65 This way, authors demonstrated that, after 12-week ospemifene treatment, up to 75% of women experienced at least a 1-point improvement in their vaginal dryness symptoms, and up to 80% in their dyspareunia symptoms.Citation66,Citation67 What is more, up to 66% and 63% of women claimed to have no or mild symptoms of vaginal drynessCitation65 and dyspareunia,Citation66,Citation67 respectively. In addition, up to 46% and 53% of women experienced at least a 2-point improvement in their symptoms of vaginal dryness and dyspareunia.Citation66,Citation67 The last numbers may be the most relevant ones, since, according to the authors, a 1-point symptom severity improvement can occur spontaneously even without any therapeutic intervention whatsoever. This was reflected in at least 14.9% of patients from Studies 310 and 821, who experienced subjective improvement in their symptoms over the 6 months without treatment since the selection and randomization process, vs 0.2% who experienced substantial improvement. Given that substantial improvement is much less likely to occur without treatment, the difference observed with ospemifene vs placebo reflects the true treatment effect.Citation76 According to the authors, these clinically relevant changes in vaginal dryness and dyspareunia, which also showed up following 4 weeks of treatment, along with changes in MI, suggest that ospemifene is not only effective in relieving VVA symptoms, but also in treating the cause of vaginal atrophy.

Safety and tolerability

The 60 mg ospemifene safety profile was established in more than 2,000 women participating in the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase II/III studiesCitation65–Citation69 and is based on more than 540 patient-years of treatment exposure consistent with long-term use requirements from The International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use/European Union guides. The number of 60 mg ospemifene-treated patients was 1.3 times the number of placebo-treated patients, and the number of patient-years with 60 mg ospemifene treatment was 2.0 times the number of patient-years with placebo treatment.Citation65–Citation69

Daily 60 mg/day ospemifene treatment was generally well tolerated both in the short and long term, with an AE global incidence of 67.6%, mostly mild to moderate. Severe AE incidence was 2.6% for 60 mg ospemifene and 1.8% for placebo, with a low rate of severe treatment-related AEs in both groups (0.6% and 0.1%, respectively).Citation65–Citation69

Global discontinuation rate was 14.6% for 60 mg ospemifene and 12.8% for placebo, and discontinuation rate due to AEs was 7.6% and 3.7%, respectively. With an AR incidence of 30.4%, hot flashes were the most frequent 60 mg ospemifene-related AEs, with at least one episode in 7.5% of patients vs 2.6% in the placebo group. This frequency was lower than that reported for tamoxifen, raloxifene, toremifene, and bazedoxifene.Citation65–Citation69 Other common AEs occurring in ≥1/100 of patients in any group are presented in .

Table 1 Summary of 60 mg ospemifene-related adverse events

Endometrial and breast safety

Ospemifene 60 mg endometrial safety in terms of hyperplasia and carcinoma risk was established in the clinical development program as no clinically relevant effect was noted in endometrial histology following 1 year of treatment, except for a single case of simple hyperplasia without atypia approximately 3 months after the last dose. In most patients (81.8%), the endometrium remained atrophic after 12-month 60 mg ospemifene treatment. A mean 0.8 mm increase in endometrial thickness was observed in 60 mg ospemifene-treated patients vs 0.06 mm with placebo, with no significant differences in the percentage of patients with ≥5 mm endometrial thickness between both arms (6.6% for ospemifene vs 2.62% for placebo; P=0.2). Additionally, there was no increase in vaginal bleeding incidence in the 60 mg ospemifene-treated women (0.9%) vs placebo (0.5%) (P=0.4).Citation77

Regarding the breast, clinical evidence also suggests a beneficial effect of 60 mg ospemifene as it demonstrated a 2% annual reduction in the incidence of abnormal findings (although not clinically significant) at breast palpation, and a 4% annual reduction in mammography findings. However, in the placebo group, abnormal mammography results increased by 2.2% after 1 year. AR rate in the breast was similar between 60 mg ospemifene and placebo (2.5% vs 2.2%, respectively).

Cardiovascular safety and venous thromboembolism

The results from all Phase II/III studies showed no 60 mg ospemifene-associated cardiovascular event risk increase. However, the annual incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) episodes with 60 mg ospemifene was 1.6%. Although the incidence was lower than with other SERMs such as bazedoxifene (4.2%)Citation78 or raloxifene (4.7%),Citation79 it suggests that VTE risk cannot be ruled out.

Safety in bone, coagulation, lipid, and weight markers

Additionally, 60 mg ospemifene did not show any significant effect on most bone turnover markers in women without osteoporosis,Citation49 or on coagulation,Citation65–Citation69 lipidCitation65–Citation69 or weightCitation65–Citation69 parameters.

Discussion and conclusion

Menopause is a natural aging process and represents a challenge for women’s preventive healthcare and quality of life,Citation80 even though most women do not have such perception.Citation25,Citation81 With lifespan increase, women will live in a postmenopausal state for more than one third of their lives, experiencing symptoms related to physiological changes associated with estrogen deficiency which affect nearly all body systems chronically.Citation13,Citation80 However, whereas hot flashes and night sweats are the most generally recognized menopausal symptoms,Citation82 and although 50% of menopausal women have vaginal discomfort,Citation76 today, most women still have little awareness of VVA, they have absolutely no idea about the origin of their symptoms,Citation25 and they even ignore this as a chronic condition requiring treatment.Citation25 This lack of awareness is an issue of concern, especially considering that these women are living a life period where these symptoms can have a greater impact on them.Citation25 Therefore, it should be highlighted that menopause is a significant health problem, and that its management is a challenge for the physician, who should probe into vaginal symptoms and talk with patients about what they themselves consider as an embarrassing issue, but which will really improve their quality of life,Citation13 along with their sexual sphere and self-esteem. A greater dissemination of information on vulvar and vaginal health in postmenopausal women and on the importance of an effective treatment would contribute to a greater defense and active participation in the therapeutic decision-making process.Citation82 This is all the more important as not all current VVA treatments are adequate for all postmenopausal women, and not all women adapt to their convenience and administration mode or respond favorably in terms of efficacy and safety.

The decrease in estrogen therapy use for menopausal symptoms after the WHI study’s safety resultsCitation9 opened the way for nonhormonal alternative therapies to treat VVA symptoms, given that concerns about the potential stimulating effects of estrogens are obvious with local vaginal therapy.Citation81 The use of over-the-counter moisturizers and lubricants provides temporary relief of symptoms and is recommended in postmenopausal women with mild-to-moderate symptoms,Citation21 but they do not treat the underlying condition.

The lack of therapeutic adherence shown by up to 44% of postmenopausal women participating in the REVIVE survey, who dropped out of at least one VVA treatment,Citation81 is a clear warning about the limitations of current treatments. Apart from the dissatisfaction these women have in terms of safety and efficacy with over-the-counter products and medically prescribed vaginal therapies, 12%–20% claim they are uncomfortable to apply, interfere with sexual spontaneity, increase itching and burning sensation in the vulvar area, and produce vaginal flow.Citation81 Many other women do not feel comfortable with the treatment’s vaginal insertionCitation25 and identify the vaginal route as a limitation. What is more, 33%–43% of postmenopausal women in Europe would prefer oral treatment.Citation81

Selectively targeted SERMs against VVA’s underlying physiopathology could be an alternative to local estrogen or systemic hormone therapy in the management of VVA symptoms, apart from moisturizers and lubricants. However, ospemifene is the only marketed SERM which has demonstrated an estrogen agonist effect in the vaginal epithelium. It is the first nonhormonal, nonestrogenic drug indicated for moderate-to-severe VVA treatment in women not eligible for vaginal estrogen therapy,Citation83 as outlined in its data sheet. Ospemifene treats the underlying cause of vaginal dryness and dyspareunia, regenerating vaginal cells, improving lubrication, and reducing pain during sexual intercourse.Citation74–Citation76 VVA symptoms improve in most women receiving ospemifene,Citation72 and they begin to revert following the first 4 weeks. Physiological improvements endure for up to 1 year of daily ospemifene use, as well as those related to all sexual function aspects. Apart from its proven safety profile in the endometrium and the bone and cardiovascular systems, its safety in the breast makes it the first VVA oral treatment not contraindicated in women with a previous history of breast cancer who have completed treatment.Citation84

Disclosure

Dr Santiago Palacios had a financial relationship (lecturer, member of advisory boards and/or consultant) with Pfizer, Servier, Amgen, MSD, Preglem, Gynea, Sandoz, Procare Health, Bayer, MSD, Serelys and Shionogi. Dr Santiago Palacios has been a symposium speaker or advisory board member and has received research grants and/or consulting fees Servier, Pfizer, GSK, Abbott, Ferrer, Bioiberica, Shionogi, Amgen, Novo Nordisk, Teva, Bayer Healthcare, Serelys and Gedeon Ritcher. Dr María Jesús Cancelo has been a symposium speaker or advisory board member for Shionogi, Amgen, Grünentahal, MSD.

References

- Mac BrideMBRhodesDJShusterLTVulvovaginal atrophyMayo Clin Proc2010851879420042564

- PortmanDJGassMLVulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference PanelGenitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health and The North American Menopause SocietyClimacteric201417555756325153131

- DavilaGWSinghAKarapanagiotouIAre women with urogenital atrophy symptomatic?Am J Obstet Gynecol2003188238238812592244

- StoneSCMickalARyePHPostmenopausal symptomatology, maturation index, and plasma estrogen levelsObstet Gynecol19754566256271095996

- GassMLCochraneBBLarsonJCPatterns and predictors of sexual activity among women in the Hormone Therapy trials of the Women’s Health InitiativeMenopause201118111160117121983008

- HuangAJMooreEEBoykoEJVaginal symptoms in postmenopausal women: self-reported severity, natural history, and risk factorsMenopause201017112112619574936

- PalaciosSAdvances in hormone replacement therapy: making the menopause manageableBMC Womens Health200882219038018

- HsiaJSimonJALinFPeripheral arterial disease in randomized trial of estrogen with progestin in women with coronary heart disease: the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement StudyCirculation2000102182228223211056097

- RossouwJEAndersonGLPrenticeRLRisks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trialJAMA2002288332133312117397

- RobertsHManaging the menopauseBMJ2007334759673674117413174

- NotelovitzMLenihanJPMcDermottMKerberIJNanavatiNArceJInitial 17 beta-estradiol dose for treating vasomotor symptomsObstet Gynecol200095572673110775738

- UtianWHShoupeDBachmannGPinkertonJVPickarJHRelief of vasomotor symptoms and vaginal atrophy with lower doses of conjugated equine estrogens and medroxyprogesterone acetateFertil Steril20017561065107911384629

- SturdeeDWPanayNInternational Menopause Society Writing GroupRecommendations for the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophyClimacteric201013650952220883118

- SimonJAIdentifying and treating sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women: the role of estrogenJ Womens Health (Larchmt)201120101453146521819250

- SucklingJLethabyAKennedyRLocal oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal womenCochrane Database Syst Rev20064CD001500

- ReesMPerez-LopezFRCeasuIEMAS clinical guide: low-dose vaginal estrogens for postmenopausal vaginal atrophyMaturitas201273217117422818886

- Al-BaghdadiOEwiesAATopical estrogen therapy in the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy: an up-to-date overviewClimacteric200912291105

- SantenRJAllredDCArdoinSPPostmenopausal hormone therapy: an Endocrine Society scientific statementJ Clin Endocrinol Metab2010957 Suppl 1s1s6620566620

- LabrieFCusanLGomezJLEffect of one-week treatment with vaginal estrogen preparations on serum estrogen levels in postmenopausal womenMenopause2009161303618820592

- Eugster-HausmannMWaitzingerJLehnickDMinimized estradiol absorption with ultra-low-dose 10 microg 17beta-estradiol vaginal tabletsClimacteric201013321922720423242

- No authors listedManagement of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause SocietyMenopause201320988890223985562

- Sanchez-BorregoRManubensMNavarroMCPosition of the Spanish Menopause Society regarding vaginal health care in postmenopausal womenMaturitas201478214615024720907

- CanoAEstevezJUsandizagaRThe therapeutic effect of a new ultra low concentration estriol gel formulation (0.005% estriol vaginal gel) on symptoms and signs of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy: results from a pivotal phase III studyMenopause201219101130113922914208

- SantoroNKomiJPrevalence and impact of vaginal symptoms among postmenopausal womenJ Sex Med2009682133214219493278

- NappiREKokot-KierepaMVaginal Health: Insights, Views & Attitudes (VIVA) – results from an international surveyClimacteric2012151364422168244

- SievertLLSalibaMReherDThe medical management of menopause: a four-country comparison care in urban areasMaturitas200859172118178044

- Sanchez-BorregoRMendozaNBeltranEPosition of the Spanish Menopause Society regarding the management of menopausal symptoms in breast cancer patientsMaturitas201375329430023706280

- BigliaNPeanoESgandurraPLow-dose vaginal estrogens or vaginal moisturizer in breast cancer survivors with urogenital atrophy: a preliminary studyGynecol Endocrinol201026640441220196634

- PalaciosSManaging urogenital atrophyMaturitas200963431531819493638

- HainerBLGibsonMVVaginitisAm Fam Physician201183780781521524046

- ChenJGengLSongXLiHGiordanNLiaoQEvaluation of the efficacy and safety of hyaluronic acid vaginal gel to ease vaginal dryness: a multicenter, randomized, controlled, open-label, parallel-group, clinical trialJ Sex Med20131061575158423574713

- TedeschiCBenvenutiCResearch Group EGComparison of vaginal gel isoflavones versus no topical treatment in vaginal dystrophy: results of a preliminary prospective studyGynecol Endocrinol201228865265422316315

- GhazanfarpourMLatifnejad RoudsariRTregliaGSadeghiRTopical administration of isoflavones for treatment of vaginal symptoms in postmenopausal women: a systematic review of randomised controlled trialsJ Obstet Gynaecol201535878378725710207

- PinkertonJVStanczykFZClinical effects of selective estrogen receptor modulators on vulvar and vaginal atrophyMenopause201421330931923777900

- BerrodinTJChangKCKommBSFreedmanLPNagpalSDifferential biochemical and cellular actions of Premarin estrogens: distinct pharmacology of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens combinationMol Endocrinol2009231748519036900

- KatzenellenbogenBSKatzenellenbogenJABiomedicine. Defining the “S” in SERMsScience200229555642380238111923515

- KharodeYBodinePVMillerCPLyttleCRKommBSThe pairing of a selective estrogen receptor modulator, bazedoxifene, with conjugated estrogens as a new paradigm for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and osteoporosis preventionEndocrinology2008149126084609118703623

- KommBSA new approach to menopausal therapy: the tissue selective estrogen complexReprod Sci2008151098499219088368

- MartinkovichSShahDPlaneySLArnottJASelective estrogen receptor modulators: tissue specificity and clinical utilityClin Interv Aging201491437145225210448

- GoldsteinSRSiddhantiSCiacciaAVPlouffeLJrA pharmacological review of selective oestrogen receptor modulatorsHum Reprod Update20006321222410874566

- TeeMKRogatskyITzagarakis-FosterCEstradiol and selective estrogen receptor modulators differentially regulate target genes with estrogen receptors alpha and betaMol Biol Cell20041531262127214699072

- TaylorHSDesigning the ideal selective estrogen receptor modulator – an achievable goal?Menopause200916360961519182697

- ShanleEKXuWSelectively targeting estrogen receptors for cancer treatmentAdv Drug Deliv Rev201062131265127620708050

- MaximovPYLeeTMJordanVCThe discovery and development of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) for clinical practiceCurr Clin Pharmacol20138213515523062036

- DaviesGCHusterWJLuYPlouffeLJrLakshmananMAdverse events reported by postmenopausal women in controlled trials with raloxifeneObstet Gynecol199993455856510214833

- European Medicines AgencyFareston Summary of Product CharacteristicsEMA2014 Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000091/WC500020689.pdfAccessed June 1, 2016

- European Medicines AgencyConbriza Summary of Product CharacteristicsEMA2011 Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000913/WC500033577.pdfAccessed June 1, 2016

- DelmantoANahas-NetoJNahasEAde OliveiraMLFernandesCETraimanPEffect of raloxifene on the vaginal epithelium of postmenopausal womenEur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol2008139218719218400357

- KomiJLankinenKSDeGregorioMEffects of ospemifene and raloxifene on biochemical markers of bone turnover in postmenopausal womenJ Bone Miner Metab200624431431816816926

- MarttunenMBCacciatoreBHietanenPProspective study on gynaecological effects of two antioestrogens tamoxifen and toremifene in postmenopausal womenBr J Cancer200184789790211286468

- VardyMDLindsayRScottiRJShort-term urogenital effects of raloxifene, tamoxifen, and estrogenAm J Obstet Gynecol20031891818812861143

- VarrasMPolyzosDAkrivisCHEffects of tamoxifen on the human female genital tract: review of the literatureEur J Gynaecol Oncol2003243–425826812807236

- PolinSAAscherSMThe effect of tamoxifen on the genital tractCancer Imaging2008813514518603495

- ParsonsAMerrittDRosenAEffect of raloxifene on the response to conjugated estrogen vaginal cream or nonhormonal moisturizers in postmenopausal vaginal atrophyObstet Gynecol2003101234635212576260

- PinkertonJVShifrenJLLa ValleurJRosenARoesingerMSiddhantiSInfluence of raloxifene on the efficacy of an estradiol-releasing ring for treating vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal womenMenopause2003101455212544676

- KaganRThe tissue selective estrogen complex: a novel approach to the treatment of menopausal symptomsJ Womens Health (Larchmt)201221997598122759213

- LoboRAPinkertonJVGassMLEvaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic parameters and overall safety profileFertil Steril20099231025103819635615

- KaganRWilliamsRSPanKMirkinSPickarJHA randomized, placebo- and active-controlled trial of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for treatment of moderate to severe vulvar/vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal womenMenopause201017228128919779382

- CuiYZongHYanHLiNZhangYThe efficacy and safety of ospemifene in treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Sex Med201411248749724251418

- VoipioSKKomiJKangasLHalonenKDeGregorioMWErkkolaRUEffects of ospemifene (FC-1271a) on uterine endometrium, vaginal maturation index, and hormonal status in healthy postmenopausal womenMaturitas200243320721412443837

- KangasLUnkilaMTissue selectivity of ospemifene: pharmacologic profile and clinical implicationsSteroids20137812–131273128024055829

- QuQZhengHDahllundJSelective estrogenic effects of a novel triphenylethylene compound, FC1271a, on bone, cholesterol level, and reproductive tissues in intact and ovariectomized ratsEndocrinology2000141280982010650964

- TarasTLWurzGTDeGregorioMWIn vitro and in vivo biologic effects of Ospemifene (FC-1271a) in breast cancerJ Steroid Biochem Mol Biol2001774–527127911457665

- European Medicines AgencySenshio: European Public Assessment ReportReport No: EMEA/H/C/002780/0000London (UK)European Medicines Agency2014 Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/002780/WC500182777.pdfAccessed June 1, 2016

- BachmannGAKomiJOOspemifene Study GroupOspemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 studyMenopause201017348048620032798

- PortmanDPalaciosSNappiREMueckAOOspemifene, a non-oestrogen selective oestrogen receptor modulator for the treatment of vaginal dryness associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase III trialMaturitas2014782919824679891

- PortmanDJBachmannGASimonJAOspemifene Study GroupOspemifene, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator for treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophyMenopause201320662363023361170

- GoldsteinSRBachmannGAKoninckxPROspemifene 12-month safety and efficacy in postmenopausal women with vulvar and vaginal atrophyClimacteric201417217318223984673

- SimonJALinVHRadovichCBachmannGAOspemifene Study GroupOne-year long-term safety extension study of ospemifene for the treatment of vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women with a uterusMenopause201320441842723096251

- SimonJPortmanDMabeyRGJrOspemifene Study GroupLong-term safety of ospemifene (52-week extension) in the treatment of vulvar and vaginal atrophy in hysterectomized postmenopausal womenMaturitas201477327428124411556

- SoeLHWurzGTKaoCJDeGregorioMWOspemifene for the treatment of dyspareunia associated with vulvar and vaginal atrophy: potential benefits in bone and breastInt J Womens Health2013560561124109197

- NappiREPanayNBruyniksNCastelo-BrancoCDe VilliersTJSimonJAThe clinical relevance of the effect of ospemifene on symptoms of vulvar and vaginal atrophyClimacteric201518223324025335119

- ConstantineGGrahamSKoltunWDKingsbergSAAssessment of ospemifene or lubricants on clinical signs of VVAJ Sex Med20141141033104124443923

- ConstantineGGrahamSPortmanDJRosenRCKingsbergSAFemale sexual function improved with ospemifene in postmenopausal women with vulvar and vaginal atrophy: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trialClimacteric201518222623225252699

- EttingerBHaitHReapeKZShuHMeasuring symptom relief in studies of vaginal and vulvar atrophy: the most bothersome symptom approachMenopause200815588588918779677

- NappiREPalaciosSImpact of vulvovaginal atrophy on sexual health and quality of life at postmenopauseClimacteric201417139

- ConstantineGDGoldsteinSRArcherDFEndometrial safety of ospemifene: results of the phase 2/3 clinical development programMenopause2015221364324977459

- ChristiansenCChesnutCH3rdAdachiJDSafety of bazedoxifene in a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled Phase 3 study of postmenopausal women with osteoporosisBMC Musculoskelet Disord20101113020569451

- GradyDEttingerBMoscarelliESafety and adverse effects associated with raloxifene: multiple outcomes of raloxifene evaluationObstet Gynecol2004104483784415458908

- GennariLMerlottiDValleggiFNutiROspemifene use in postmenopausal womenExpert Opin Investig Drugs2009186839849

- KingsbergSAWysockiSMagnusLKrychmanMLVulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (REal Women’s VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) surveyJ Sex Med20131071790179923679050

- ParishSJNappiREKrychmanMLImpact of vulvovaginal health on postmenopausal women: a review of surveys on symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophyInt J Womens Health2013543744723935388

- DeGregorioMWZerbeRLWurzGTOspemifene: a first-in-class, non-hormonal selective estrogen receptor modulator approved for the treatment of dyspareunia associated with vulvar and vaginal atrophySteroids201490829325087944

- European Medicines AgencySenshio Summary of Product CharacteristicsEMA2015 Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/002780/WC500182775.pdfAccessed June 1, 2016