Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the efficacy of Pelvicol xenograft use during abdominal sacrocolpopexy to repair pelvic organ prolapse (POP).

Patients and methods

A total of 27 consecutive women with symptomatic POP were included in this study. A POP-quantification system and International Continence Society classification were used. Functional and anatomical outcomes were assessed. Subjective outcomes and physical activity after surgery were evaluated due to modified quality of life questionnaire.

Results

Median follow-up was 21 months (range: 16 to 41 months). Twenty-four (89%) patients were available for anatomical and subjective evaluation. Preoperative POP-quantification classification was: stage I: 11.1%, stage II: 25.9%, stage III: 48.2%, and stage IV: 14.8%. Overall, pad usage significantly decreased (mean 4.8 vs 1 pads, P=0.001). Stress urinary incontinence significantly improved after surgery in nine women (P=0.001). An additional five women were completely continent. No de-novo incontinence developed. Six women with preoperative urinary retention improved in the amount of residual urine postoperative (mean 35 vs 165 mL). Failure rate was 8.3% at 3 and 11 months after surgery, requiring a second reconstruction. There was no graft related complications or graft rejections necessitating removal occurring. Response rate of the questionnaire was 67%. Two women reported no interference in physical activity after 2 postoperative months, five women after 5 months, and five women 1 year later. Pelvic pain (vaginal pain) was partly improved in eight patients, postoperatively, and ten patients had complete resolution of pain after surgery.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that abdominal sacrocolpopexy is an effective surgical treatment in correcting POP. The use of Pelvicol is associated with a high recurrence rate and increased failure rate compared to traditional sacrocolpopexy with mesh. Larger clinical trials to evaluate the functional and anatomical outcomes are needed.

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is highly prevalent in women (30%–50%), with a 11% lifetime risk of requiring surgical repair.Citation1–Citation4 The cause of prolapse is unknown, however risk factors include age, increasing number of gravidity and vaginal deliveries, obesity, chronic cough, constipation, and a history of hysterectomy.Citation1,Citation3 Urinary and fecal incontinence, vaginal ulceration, problems with defecation, and sexual dysfunction are the most troublesome symptoms.Citation1

Sacrocolpopexy is the gold standard procedure for POP with excellent anatomical and functional outcomes.Citation4 It can be performed abdominally, laparoscopically or robotically.Citation5,Citation6 There are a number of advantages to a patient with laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy versus open procedure. Pain is reduced due to smaller incisions and recovery times are shorter.Citation5,Citation6 The use of an implant to substitute the deficient level support significantly improves the long-term anatomical results.Citation5 Macroporous polypropylene grafts are more commonly used, however are associated with complications such as erosion and pain, which can render the patient in a worse state of health.Citation5,Citation7 To reduce the complication rates, implant of native tissue grafts has been gaining popularity. Bioderived matrices have been used and are highly tolerated as they induce a mild inflammatory response, however, little scientific data supporting the use of xenografts is available.Citation7

With this in mind, we aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the xenograft Pelvicol abdominal sacrocolpopexy (ASC) and concomitant colposuspension.

Patients and methods

We performed a single center study including 27 patients undergoing ASC treatment for POP between March 2011 and March 2013. All patients underwent preoperative urodynamic studies as a standard practice. Prolapse evaluation was conducted using a posterior Sims speculum placed in the anterior vaginal fornix.Citation8 Diagnosis of stress urinary incontinence (SUI), mixed incontinence, detrusor over activity, voiding dysfunction and residual urinary were documented.

Data was prospectively collated and included patient demographics (age, body mass index, parity, American Society of Anesthesiologists score [I–IV], the classification of POP according with the International Continence Society and POP-quantification [POP-Q] system criteria, and a comparison of the pre and post-operative symptoms based on pad usage, voiding frequency, nocturia, residual urine, and dysuria).Citation8 Prolapse reduction was performed for women with advanced POP (stage II–IV). At least 1 year after surgery, women who underwent ASC were asked to complete a validated standardized prolapse quality of life questionnaire.Citation9 The Clavien-modified grading system was used to classify any complications. The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the University Medical Center Goettingen (approval 5/4/15). All patients provided written informed consent for this study. Two experienced surgeons with over 10 years of female urological experience at a tertiary referral center performed all procedures. During ASC, we substituted the porcine graft (Pelvicol® 2×4 cm, Bard, UK) in all patients. Women diagnosed with a prolapse reduction, either with or without SUI, underwent incontinence surgery by Burch procedure at the time of ASC. All patients were permanently catheterized for 5 days postoperatively. A prophylactically antibiotic with cefuroxime 1.5 g intravenously as a single shot was given to all women perioperatively.

Patients were followed-up routinely at 3, 6 and 12 months. Women in these practices were asked at each postoperative visit about lower urinary tract symptoms, SUI, frequency and urgency including anatomical evaluation and subjective outcomes evaluation. Postoperative anatomic failure was defined as POP-Q >II.

Operative technique

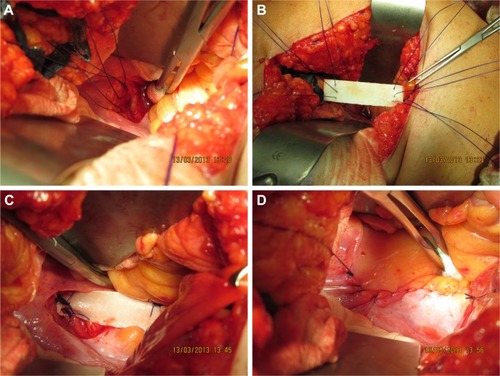

The procedure began with bladder catheterize and insertion of vaginal dressing forceps with a fixed swab into the vagina. Procedures were performed at the Pfannenstiel incision and transperitoneal in all patients. Alternatively, a median laparotomy was occasionally used. The vaginal stump was exposed and the peritoneum was opened up to reveal in case of any previous hysterectomy. If a previous hysterectomy was indicated a supracervical hysterectomy was performed and the xenograft was fixed onto the cervical stump, in any case of uterus preservation the fixation was performed onto the posterior cervical wall. After exposure and palpation of the promontorium, the peritoneum was opened above the promontorium and the presacral fat tissue was loosened and removed from the os sacrum (height S3–S4). This allowed for the surface of the anterior longitudinal ligament to become visible. A 4 cm long, and 2 cm wide Pelvicol implant was then inserted into the abdomen and positioned longitudinally between the promontorium and the vaginal stump. The xenograft was fixed onto the vaginal stump through three single sutures (Ethibond 0; Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA). While pushing up the vaginal stump with the swab intravaginal, however, care was taken to ensure that the needle did not grasp the swab and stitch it to the surface. Three simple interrupted stiches were then stitched into the longitudinal ligament and the proximal end of the xenograft was attached to the longitudinal ligament. Peritonealization of the vaginal stump was then undertaken. Peritoneal closure above the xenograft was then performed through continuous suture (Vicryl 3.0; Ethicon) (). ASC was followed by Burch colposuspension as a standard technique.

Figure 1 Abdominal sacrocolpopexy.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 17 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) program. We used a two-sample t-test for continuous data and Chi square test for dichotomous data. The significance level was set at a P-value of <0.05.

Results

A total of 27 patients were included. Patient demographic are shown in . The median follow-up was 21 months (range: 16 to 41 months). Baseline and end of study symptom comparisons are displayed in .

Table 1 Preoperative characteristics of patients

Table 2 Urinary symptoms preoperative and at follow-up

SUI had significantly improved after surgery in 14 women (P=0.001). The use of continence pads significantly decreased postoperatively (mean 1 vs 4.8 pads, P=0.001). None of the preoperatively continent patients developed de novo incontinence. All women with preoperative urinary retention emptied their bladder without significant urine residual postoperatively.

Two patients had a prolapse recurrence (failure rate 8.3%) after ASC (one patient POP-Q I and one patient POP-Q II). The time to anatomical failure was 3 and 11 months after surgery. Both underwent secondary operations with ASC with xenograft. Additional procedures and perioperative complications are shown in .

Table 3 Additional procedure and perioperative complications and anatomical failure

There were no graft related complications (GRC). There were no graft rejections necessitating removal. A simple urinary tract infection occurred in two women, both treated successfully with antibiotics. Two other women developed complications, one a wound infection which healed successfully and another with an incision hernia.

A total of 18 patients (67%) responded to the postoperative questionnaire. Of the women who reported that prolapse interfered substantially with their ability to physical activity, two women reported no interference and ten women described no intrusion. Pelvic pain (vaginal pain) improved in eight patients (44%) postoperatively, and ten patients (56%) had complete resolution of pain. Those patients who suffered voiding difficulties (n=6), four had complete resolution (67%). The majority of the patients (94%) were satisfied with the outcome while only one woman was not satisfied, with 83% of patients saying that they would recommend the procedure.

Discussion

Abdominal sacrocolpopexy is highly effective at anatomically correcting POP involving the vaginal apex.Citation10,Citation11 The goal of this study was to evaluate the functional and anatomical outcomes after ASC with xenograft Pelvicol and concomitant colposuspension. The prolapse failure rate in our study was 7.4%. Current studies on sacrocolpopexy using xenograft have demonstrated a higher failure rate. Quiroz et al showed that Pelvicol had a significantly higher anatomical relapse rate in ASC compared to synthetic implants (11% vs 7%).Citation12 A recent randomized controlled trial showed a 7% failure rate in the Pelvicol group.Citation13 Deprest et al described a similarly significant higher prolapse recurrence rate at vault prolapse in women who underwent sacrocolpopexy with Pelvicol compared to synthetic mesh (21% vs 3%).Citation14 However, they did not find any significant difference in functional outcome.

The initial drive to using xenograft was based on early experimental reports. These data demonstrated that xenograft induce a smaller and moderately anti-inflammatory reaction and a lower risk to local complications.Citation15,Citation16 Our experience confirmed this hypothesis. In our study, we did not notice any GRC. This may be due to a shorter follow-up period. Deprest et al reported no significant differences in the GRC rate between Pelvicol and the control group in a median follow-up of 34 months (12% to 11%).Citation14 Quiroz et al observed an even higher GRC rate with Pelvicol compared with synthetics.Citation12 We peritonealized the xenograft to reduce the infection rate and avoid contact with the intestine.

The incidence of POP with concomitant SUI is not well established and is reported as ranging from 15% to 80%.Citation17,Citation18 The replacement of a prolapse into the intended postoperative position could be more at risk for postoperative SUI in currently continent women because of the change in the vaginal axis. Thus, in the continent patient with POP, the surgeon is left with one of three options: reserving a second incontinence operation for women whose SUI symptoms warrant it; a prophylactic anti-incontinence procedure with the risk of overtreatment, or a postoperative wait and watch approach. Several studies have indicated various incontinence rates after different concomitant prophylactic anti-incontinence operations.Citation19,Citation20 The Colpopexy and Urinary Reduction Efforts study described significantly higher postoperative SUI rates in women after ASC compared with women after ASC and prophylactic anti-incontinence procedure (Burch operation) in a 2-year follow-up (41% vs 26%).Citation21 Contrarily, Constantini et al reported a significantly higher postoperative incontinence rate in women who underwent ASC and concomitant Burch compared with women after ASC without prophylactic anti-incontinence operation in a 8-year follow-up (29% vs 16%).Citation22 The discrepancies with outcomes in both trials are probably due to the sacropexy technique, patient enrolment and length of follow-up. Cosson et al reported that only 34% of women with prolapse and preoperative urinary incontinence achieved a complete postoperative continence.Citation23 Our results confirm Brubaker et al’s observations.Citation21 Frequency of postoperative incontinence after ASC and Burch was low. The odds of suffering SUI after ASC were not great in patients who had concomitant Burch colposuspension. In our study, multivariate analyses showed that concomitant colposuspension decreased the risk of postoperative SUI without increasing the perioperative morbidity, voiding dysfunction and urinary retention. In our opinion, all patients must be counselled preoperative about the opportunity of a prophylactic anti-incontinence procedure and their advantages and disadvantages.

Limitations

There are some limitations to our study. The number of enrolled patients in the study was small (n=27), the follow-up period was short (mean 21 months), and the percentage of patients who responded to the questionnaire was quite low (68%). Nonetheless, our study was strengthened by the meticulous use of our protocol, which yielded significant improvements in our patients. However, a randomized controlled trial could shed more light.

Conclusion

Abdominal sacrocolpopexy is an efficient treatment for genital prolapse with excellent anatomical and functional outcomes and a significant postoperative reduction of all assessed symptoms. The usage of the porcine graft, Pelvicol, is associated with low GRCs and high failure rate. Additional Burch colposuspension during sacrocolpopexy is an effective prophylaxis for postoperative incontinence. In future, larger and prospective, randomized clinical trials and a long-term follow-up are needed to further evaluate durability, anatomical outcomes and patient satisfaction after ASC with xenograft.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HendrixSLClarkANygaardIAragakiABarnabeiVMcTiernanAPelvic organ prolapse in the Women’s Health Initiative: gravity and gravidityAm J Obstet Gynecol200218661160116612066091

- OlsenALSmithVJBergstromJOCollingJCClarkALEpidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinenceObstet Gynecol19978945015069083302

- SwiftSEThe distribution of pelvic organ support in a population of female subjects seen for routine gynecologic health careAm J Obstet Gynecol2000183227728510942459

- MaherCBaesslerKGlazenerCMAdamsEJHagenSSurgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in womenCochrane Database Syst Rev20073CD00401417636742

- NygaardIEMcCreeryRBrubakerLAbdominal sacrocolpopexy: a comprehensive reviewObstet Gynecol2004104480582315458906

- RozetFMandronEArroyoCLaparoscopic sacral colpopexy approach for genitourinary prolapse: experience with 363 casesEur Urol200547223023615661419

- ClaerhoutFVerbistGVerbekenEKonstantinovicMDe RidderDDeprestJFate of collagen-based implants used in pelvic floor surgery: a 2-year follow-up study in a rabbit modelAm J Obstet Gynecol2008198194.e1e618166318

- BumpRCMattiassonABøKThe standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunctionAm J Obstet Gynecol1996175110178694033

- DigesuGAKhullarVCardozoLRobinsonDSalvatoreSP-QOL: a validated questionnaire to assess the symptoms and quality of life of women with urogenital prolapseInt Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct200516317618115875234

- BrubakerLCundiffGWFinePAbdominal sacrocolpopexy with Burch colposuspension to reduce urinary stress incontinenceN Engl J Med2006354151557156616611949

- DianaMZoppeCMastrangeliBTreatment of vaginal vault prolapse with abdominal sacral colpopexy using prolene meshAm J Surg2000179212612810773148

- QuirozLHGutmanREShippeySAbdominal sacrocolpopexy: anatomic outcomes with Pelvicol, autologous and synthetic graft materialsAm J Obstet Gynecol20081985557.e1e518455533

- HviidUHviidTVRudnickiMPorcine skin collagen implants for anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomized prospective controlled studyInt Urogynecol J201021552953420165833

- DeprestJDe RidderDRooversJPWerbrouckECoremansGClaerhoutFMedium term outcome of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with xenografts compared to synthetic graftsJ Urol200918252362236819762041

- SongZPengZLiuZYangJTangRGuYReconstruction of abdominal wall musculofascial defects with small intestinal sub-mucosa scaffolds seeded with tenocytes in ratsTissue Eng Part A20131913–1415431553 Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3665322/Accessed February 08, 201723402600

- KonstantinovicMLLagaePZhengFVerbekenEKDe RidderDDeprestJAComparison of host response to polypropylene and non-cross-linked porcine small intestine serosal-derived collagen implants in a rat modelBJOG20051121554156016225578

- FianuSKjaeldgaardALarsonBPreoperative screening for latent stress urinary incontinence in women with cystoceleNeurourol Urodyn199543

- RichardsonDBentAOstergardDThe effect of uterovaginal prolapse on urethrovesical pressure dynamicsAm J Obstet Gynecol19831469019056683932

- CrossCACespedesRDMcGuireEJTreatment results using pubovaginal slings in patients with large cystoceles and stress incontinenceJ Urol19971584314349224317

- GordonDGroutzAWolmanILessingJBDavidMPDevelopment of postoperative urinary stress incontinence in clinically continent patients undergoing prophylactic Kelly plication during genitourinary prolapse repairNeurourol Urodyn199918319319810338439

- BrubakerLCundiffGFinePA randomized trial of colpopexy and urinary reduction efforts (CARE): design and methodsControl Clin Trials200324562964214500059

- CostantiniELazzeriMBiniVDel ZingaroMZucchiAPorenaMPelvic organ prolapse repair with and without prophylactic concomitant Burch colposuspension in continent women: a randomized, controlled trial with 8-year followupJ Urol2010185622362240

- CossonMBoukerrouMNarducciFOccelliBQuerleuDCrepinGLong-term results of the Burch procedure combined with abdominal sacrocolpopexy for treatment of vault prolapseInt Urogynecol J2003142104107