Abstract

Endometriosis is a highly enigmatic disease with multiple presentations ranging from infertility to severe pain, often causing significant morbidity. Video-assisted laparoscopy (VALS) has now replaced laparotomy as the gold standard for the diagnosis and management of endometriosis. While imaging has a role in the evaluation of some patients, histologic examination is needed for a definitive diagnosis. Laboratory evaluation currently has a minor role in the diagnosis of endometriosis, although studies are underway investigating serum markers, genetic studies, and endometrial sampling. A high index of suspicion is essential to accurately diagnose this complex condition, and a multidisciplinary approach is often indicated. The following review discusses laparoscopic diagnosis of endometriosis from the pre-operative evaluation of patients suspected of having endometriosis to surgical technique for safe and adequate laparoscopic diagnosis of the condition and postsurgical care.

Introduction

Endometriosis is an enigmatic and complex disease characterized by benign endometrial glands and stroma occurring outside of the uterine cavity. The disease causes significant frustration for both physicians and patients. Second only to leiomyomata in frequency of gynecologic disorders, endometriosis may cause pain, infertility, and a multitude of other symptoms, many of which mislead even the most experienced diagnosticians. More than just an individual issue, endometriosis incurs great societal cost in terms of psychological morbidity, work absenteeism, and disability compensation. Endometriosis carries an estimated prevalence of 6%–10% among women, most commonly of reproductive age. This increases to 35%–50% of women with pelvic pain, infertility, or both.Citation1,Citation2 Prevalence is difficult to accurately assess, given that many women with endometriosis are asymptomatic and many do not seek medical attention for their symptoms. Known to be a largely estrogen-dependent entity, endometriosis has also been reported in postmenopausal women as well as men.Citation3,Citation4

Clinical evaluation

Diagnosis of endometriosis first and foremost requires a high index of suspicion, as symptomatology may vary widely and disease course is largely unpredictable.Citation5 A thorough history and careful physical exam are imperative. The most common presenting symptoms are pelvic pain and infertility. Dysmenorrhea, typically beginning 1–2 days prior to the start of menses is a classic symptom, although pelvic pain often occurs outside of the menstrual cycle as well. Pain may vary in description from dull to sharp, and many report a feeling of pressure or fullness of the pelvis. Pain may be unilateral or bilateral and often radiates to the low back and down the legs.

Dyspareunia, particularly with deep penetration, is also a hallmark of the disease and is usually secondary to endometrial implants on the uterosacral ligaments as well as immobility of pelvic organs that are entrapped by infiltrative disease and dense adhesions.

Fifteen to twenty percent of patients with endometriosis report abnormal uterine bleeding, most commonly premenstrual spotting and menorrhagia.Citation5 Bleeding is usually in an ovulatory pattern, although approximately 15% of endometriosis patients also have anovulatory bleeding.

Interestingly, endometriosis has long shown a familial association.Citation1 Over 30 years ago, it was recognized that first-degree relatives of women with severe endometriosis carried a six-fold greater risk of having the disease than relatives of women without endometriosis.Citation6 Familial and genetic studies are ongoing, but a family history of endometriosis may elevate suspicion of the disease.

Signs of endometriosis include a fixed, retroverted uterus, uterosacral nodularity and tenderness (best evaluated on rectovaginal exam), and enlarged, tender ovaries that are often fixed to the posterior uterus or pelvic sidewall. Speculum exam may reveal endometriotic implants on the cervix or upper vagina. Fifteen percent of patients will demonstrate lateral displacement of the cervix on digital or speculum exam.Citation5

The presence of leiomyomata should also raise the clinician’s suspicion of endometriosis.Citation7 A 2010 study demonstrated an 86% prevalence of endometriosis in patients undergoing surgery for uterine fibroids.Citation8 Women with fibroids and infertility, in particular, are likely to have concomitant endometriosis.Citation9

Extragenital endometriosis, discussed in a later section, may present very unpredictably, with symptoms ranging from gastrointestinal disturbances in bowel endometriosis to catamenial pneumothorax in thoracic endometriosis. However, dyschezia and dysuria may be present even when endometriosis does not directly involve the bowel or bladder.Citation10 It is critical during the preoperative interview and evaluation to inquire about bowel and bladder symptoms. When indicated, colonoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and/or computed tomography (CT) should be obtained for pre-operative planning. Appropriate consultation with a urologist and/or colorectal surgeon may be required.

Imaging studies

Imaging studies for endometriosis in general have limited value. The presence of an adnexal mass consistent with endometrioma is an exception.Citation11 Transvaginal sonography (TVS) remains the method of choice for evaluation of an adnexal mass and has the added benefit of a lack of radiation exposure. We perform TVS on all patients suspected of having endometriosis to evaluate for endometriomas and fibroids. Endometriomas have distinct features on ultrasound, most commonly as unilocular cysts with a homogenous ‘ground glass’ appearance.Citation12 The presence of an endometrioma should alert the clinician to the possibility of moderate to advanced stage disease.Citation13 One concerning exception is the postmenopausal patient, in which ovarian cysts with ‘ground glass’ appearance are associated with a 44% risk of malignancy.Citation12 Additionally, TVS may play a role in the evaluation of disease involving the bladder and rectum.Citation14,Citation15

CT may be useful in diagnosing bowel endometriosis in the presence of colon distension.Citation15,Citation16 CT evidence of hydronephrosis or hydroureter in patients with pelvic pain or a history of endometriosis should raise suspicion of genitourinary involvement.Citation17 Radiation exposure should be taken into consideration.

MRI also has limited use in the diagnosis of endometriosis. It may be helpful in confirming the identification of an adnexal mass as an endometrioma when TVS is equivocal. MRI should also be considered if the clinician is suspicious of ureteral involvement, and it may be useful in evaluation of anatomy when extensive pelvic adhesions are anticipated.Citation18

The role of double-contrast barium enema (DCBE) in the evaluation of rectovaginal endometriosis is controversial.Citation15 Some studies have shown encouraging accuracy in predicting the need for intestinal surgery in endometriosis cases.Citation19,Citation20 DCBE was found in one report to be superior to MRICitation21 but in another to be inferior to rectal ultrasound.Citation21 However, other studies have demonstrated lower sensitivity of DCBE for rectovaginal disease.Citation22,Citation23 DCBE does not permit examination of the entire bowel wall and gives no information regarding depth of infiltration but may provide useful preoperative planning in some cases of suspected severe disease.Citation15

Laboratory evaluation

No serum marker has yet been identified that is useful in the diagnosis of endometriosis. Cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) is frequently elevated in endometriosis, particularly in Stage III/IV disease and in the presence of endometriomas; however, correlation with laparoscopically diagnosed disease is still limited at best and is largely not considered clinically useful.Citation10,Citation11,Citation24 Numerous additional biomarkers are currently being studied, both in isolation and in combination testing. Additionally, genetic markers and evaluation of endometrial biopsy samples are showing promise as less invasive means of diagnosis.Citation1,Citation25,Citation26 At this time, however, none of these methods of evaluation have approached the diagnostic accuracy of laparoscopy.

Surgical diagnosis

Endometriosis was first described by Von Rokitansky in 1860.Citation1 The condition has historically been diagnosed and treated by laparotomy, and treatment prior to 1960 was almost exclusively achieved by abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.Citation27

Abdominal laparoscopy was first introduced as early as the 1910s;Citation28–Citation30 however, the true benefits of operative laparoscopy were only realized with the introduction of video-assisted laparoscopic surgery (VALS).Citation27,Citation31,Citation32 Before the advent of VALS, the utility of operative laparoscopy was diminished by two major drawbacks: poor visualization into the intra-abdominal cavity with one eye and the inability of the operative team to view the operative field. Both of these limitations were rectified with the introduction of VALS by Dr Camran Nezhat.Citation32

The benefits of VALS have facilitated the transition from laparotomy to laparoscopy for multiple procedures including those as uncomplicated as appendectomy and cholecystectomy as well as more complicated procedures such as bowel resection. In 1985, Nezhat reported that even extensive endometriosis, and as a result, almost all abdominal and pelvic pathologies, can be managed effectively using VALS.Citation33 The increasing application of advanced VALS is a direct consequence of surgical ingenuity and advances in laparoscopic techniques and equipment.Citation28,Citation34–Citation36

Several studies have demonstrated that outcomes with laparoscopic management of endometriosis are similar to those of laparotomy in terms of pregnancy rates, fecundity, and recurrence rates.Citation37–Citation41 A prospective, randomized controlled trial evaluating laparotomy versus VALS for the treatment of endometriomas showed similar outcomes as well and also confirmed that VALS is associated with lower analgesic requirement, earlier discharge, and shorter postoperative recovery time.Citation42 Patients experience significantly less disruption in their lives with VALS than with laparotomy and typically return to work more quickly. VALS also offers improved visualization of the abdomen and pelvis, with the ability to magnify and approach structures from angles not accessible by laparotomy, allowing for a more thorough treatment of extensive disease.Citation43,Citation44 The clear visualization afforded by VALS offers significant advantages for radical surgery for both oncologic indications as well as extensive endometriosis. Nerve-sparing radical surgery is facilitated by the ability to magnify objects and accurately dissect around the pelvic nerves.Citation45,Citation46

Technique and instrumentation

VALS for the diagnosis and management of endometriosis has become the gold standard. As minimally invasive surgery has progressed, it becomes more and more unconscionable to inflict laparotomy and its prolonged recovery on patients already afflicted with chronic pain and/or infertility, unless absolutely necessary. Furthermore, reports of endometriosis found in Pfannenstiel scars are highly suspicious for iatrogenic spread of the disease.Citation47,Citation48

Minimally invasive surgery is rapidly progressing toward microsurgery as technical advances allow for smaller and fewer incisions. At this time, the authors still prefer the 10-mm laparoscope for outstanding optics and a sharp picture. As endometriosis may present in numerous and subtle ways, an excellent visual field is imperative for the identification of possible lesions. This includes a high-quality camera, preferably with high-definition capability.

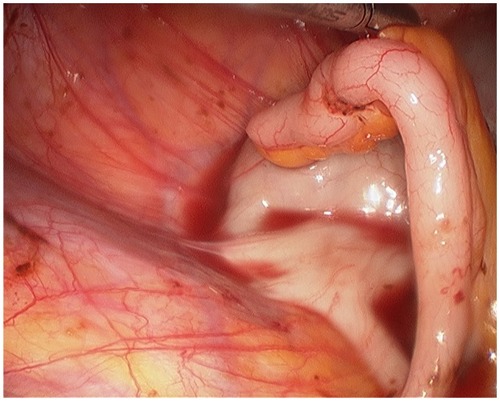

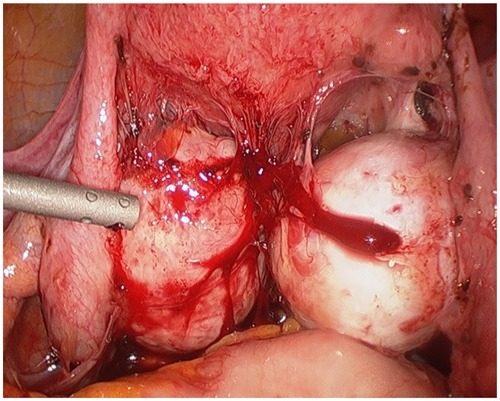

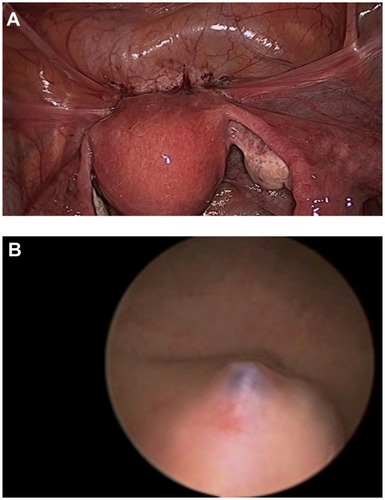

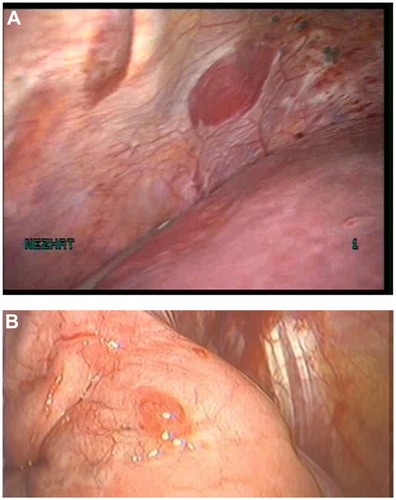

The surgeon begins with a thorough evaluation of the pelvis and abdomen. Initial entry is followed by examination of the site of entry to ensure that no injury resulted from the veress needle or trocar.Citation27 The extent of disease and any anatomical distortion should be assessed and documented with photographs. Whether to videotape a procedure is highly controversial due to the possibility of alteration and liability concerns. The location and course of vital structures is noted, including the bladder, ureters, rectosigmoid colon, and major blood vessels, as well as the uterosacral ligaments, and the ovaries and their blood supply. The pelvic and abdominal sidewalls, liver, and diaphragm are evaluated for any lesions that may be contributing to the patient’s symptoms. The surface of the uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, ovarian fossae, and cul de sac are examined. The appendix should be carefully evaluated and removal considered, as 22% of patients with pelvic endometriosis will also have endometriosis of the appendix ().Citation49 A rectovaginal exam and thorough examination of the pararectal spaces and uterosacral ligaments may reveal deep infiltrating disease and/or cul de sac obliteration (). Often, a seemingly superficial lesion on the peritoneal surface may extend for several centimeters deep into the retroperitoneal space. These ‘iceberg’ lesions can frequently be detected by probing with a blunt instrument or suction-irrigator. Careful notation should be made of the size, depth, and proximity to other anatomic structures. Provided the patient has consented and it is safe to proceed, excision may be undertaken.

Endometriosis can only be confirmed by histopathologic examination. Therefore, biopsy of suspected lesions is essential, and excision is preferable when it can be safely done. Most gynecologists are familiar with the common black, brown, or blue ‘powder burn’ appearance of peritoneal endometriosis; however, this manifestation accounts for only a minority of lesions.Citation27 Endometrial implants may appear in a number of different ways, including subtle red or white lesions, clear ‘bubble’ lesions, small hemorrhagic cysts, or white fibrotic lesions.Citation11 Stegmann et al showed that most lesions contain a mix of colors and textures and that the surgeon’s impression of whether a lesion contains endometriosis has only a 65% positive predictive value of actual histology-confirmed endometriosis.Citation50 This study confirms the importance of obtaining pathologic diagnosis of any abnormal lesion that may be safely sampled or removed. Even our team, a referral center for complex cases of endometriosis with decades of experience, is often surprised by biopsied specimens that do not appear consistent with endometriosis but which are histologically confirmed to contain endometriotic glands and stroma.

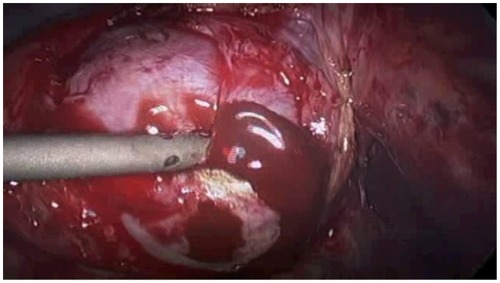

Safe laparoscopic excision of an endometriotic lesion requires acute awareness of surrounding structures. Adhesiolysis is often necessary for thorough evaluation of the pelvis. This may be accomplished with a combination of blunt or sharp dissection, electrosurgery, or ultrasonic energy. For dense adhesions, the authors prefer the CO2 laser, which has the most limited thermal spread of any available laparoscopic energy source and a very limited depth of invasion.Citation33,Citation51,Citation52 A good alternative for limited thermal spread is the PlasmaJet® (Plasma Surgical, Inc, Roswell, GA), a new technology employing excited electrically neutral argon plasma with a thermal spread of only 200 μm.Citation53

We also strongly advocate the use of hydrodissection to separate superficial peritoneal layers from underlying vital structures before excising peritoneal lesions.Citation51 To hydrodissect, a small incision is made in an area of peritoneum near the lesion but away from any vital structures. The suction-irrigator probe may then be inserted into the incision superficially and irrigation applied in order to lift the surface peritoneum from the underlying tissues. The area over the lesion may then be gently grasped and carefully dissected off using laparoscopic scissors or energy with minimal thermal spread such as those discussed above.

Endometriomas, or endometriosis-filled cysts of the ovaries, account for approximately 35% of benign ovarian cysts ().Citation44,Citation54 One-third to one-half of patients with endometriomas will have bilateral cysts.Citation55 On initial diagnostic laparoscopy, excision of an endometrioma is ideal for two reasons: first, endometriomas greater than 1 cm in size are unlikely to spontaneously resolve, and second, excision allows for pathologic examination of the tissue and diagnostic confirmation.Citation45 The risk of malignant transformation of an endometrioma is 2.5%, most commonly resulting in endometrioid carcinoma or clear cell adenocarcinoma.Citation44,Citation56,Citation57

At the conclusion of a diagnostic VALS procedure, cystoscopy should be strongly considered, particularly if any dissection has occurred near the bladder or ureters. Cystoscopy should also be a part of the diagnostic evaluation in patients with urinary symptoms such as dysuria, hematuria, or urinary urgency. Additionally, in any patient who has undergone significant enterolysis and/or cul de sac dissection, a proctoscopy with instillation of air in the rectum and irrigation of the bowel surface should be performed. The presence of bubbles with air instillation indicates bowel injury. Alternatively, dilute indigo carmine can be instilled in the rectum to evaluate for distal bowel injury.

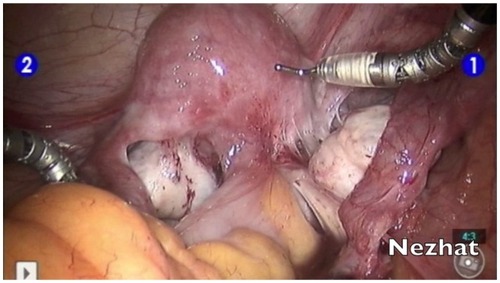

Robot assistance

More recently, the da Vinci robotic platform has been used in the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis ().Citation58–Citation60 The three-dimensional view offers excellent visualization, which may be most beneficial in identifying suspected implants. However, the robotic platform has the distinct disadvantage of offering only a unidirectional view within the abdominal cavity. It is advisable for the surgeon to first undertake a diagnostic laparoscopy to ensure that suspected endometriosis is not visible in the upper abdomen, liver, diaphragm, and appendix before docking the robot in order to proceed with examination and treatment of the pelvis. Additionally, the loss of haptic feedback is a major detriment to the identification of the fibrotic lesions characteristic of deeply infiltrating disease. However, in the treatment of endometriosis, the da Vinci may offer ease of hand tremor and more instinctual movement of the wristed instruments. As such, it can help to bridge the gap between VALS and laparotomy for surgeons who are uncomfortable performing traditional VALS.

Staging

Several different criteria for the classification of endometriosis have been developed. Unfortunately, all classifications are subjective and correlate poorly with symptoms and fertility outcomes.Citation11 The most widely accepted is that proposed in 1996 by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), rating the extent of endometriosis on a scale of I (minimal) to IV (severe).Citation61–Citation63 The ASRM system has the benefit of allowing clinicians to communicate effectively concerning prognosis and treatment but does not correlate well with symptoms nor a patient’s likelihood of conception following treatment.Citation64 Additional classification systems have been proposed by Batt et al,Citation65 Adamyan,Citation66 and Chapron et al.Citation67 In 2004, the ENZIAN classification was introduced and may serve as an adjunct to the ASRM classification for deeply infiltrative disease.Citation68 Adamson and Pasta developed the Endometriosis Fertility Index, which has been validated as a means of predicting non-IVF pregnancy rates in patients who have undergone surgical evaluation of endometriosis.Citation69,Citation70 The American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL) is in the process of developing a new classification system for endometriosis.Citation71 More recently, a new staging system based on ultrasonographic findings of deep, infiltrating disease has been suggested as well.Citation72 While interest is high, the establishment of a widely accepted and clinically significant classification system remains elusive.

Extragenital endometriosis

Endometriosis occurs most commonly in the pelvis, particularly on the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and anterior and posterior cul de sac areas. When endometriosis occurs outside of the pelvis, it is termed “extragenital endometriosis”. A 2004 review of 379 cases of endometriosis found a prevalence of 8.4% in extragenital locations.Citation73 Of these, 32.3% involved the intestinal tract, 5.9% involved the urinary tract, and 61.8% involved other areas, including abdominal scar, inguinal canal, umbilicus, and perineum. While pain was the most common presenting symptom, cyclical pain occurred in only approximately 40%. Palpable mass was also present in approximately 40%, most notably in low transverse abdominal scars, indicating a possible iatrogenic etiology.

Bowel endometriosis

The rectosigmoid colon is the most commonly involved site of endometriosis beyond the gynecologic organs, followed by the appendix. Endometriosis of the bowel may manifest in any number of ways, including hematochezia, melena, constipation, diarrhea, bloating, nausea, and emesis. Again, symptoms may be cyclic but very frequently are not. Imaging as discussed above should be obtained for pre-operative management when indicated. A colonoscopy is indicated in patients with melena or hematochezia. A multidisciplinary approach with the involvement of a colorectal surgeon should be strongly considered. Management of bowel endometriosis was first reported in October 1988 at the 44th Annual Meeting of the American Fertility Society in Atlanta, GA and may be accomplished by multiple techniques depending on the extent of infiltration and therapeutic goals of the patient. Surgical management may include superficial shaving, disk excision, or segmental bowel resection.Citation51,Citation74–Citation78

Endometriosis of the urinary tract

Urinary tract endometriosis is estimated to occur in 1%–5% of endometriosis cases, affecting the bladder, ureter, and kidney in a ratio of 40:5:1.Citation79–Citation82 Complaints that should alert the clinician to possible urinary tract involvement include urgency, frequency, suprapubic pain, urge incontinence, flank or back pain, and dyspareunia. Hematuria is reported in 33% of cases but is only cyclic in approximately half of these patients.Citation79 When urinary tract involvement is suspected, imaging must be performed to evaluate for hydronephrosis or hydroureter. CT, MRI, or intravenous pyelogram (IVP) may help to localize a lesion compressing the ureter. Cystoscopy will reveal bladder mucosal involvement or mass effect and may be used for pre-operative ureteral stent placement (). In the event of significant renal compromise, percutaneous nephrostomy may be required prior to definitive surgery. Careful ureterolysis should be performed in all patients prior to removing an endometriotic nodule in order to identify the course of the ureter and prevent injury. The authors frequently administer intraoperative intravenous indigo carmine in order to alert to any ureteral injury at time of ureterolysis. If the mucosa of the bladder or ureter is involved with endometriosis, segmental resection and reanastomosis is the treatment of choice.Citation79–Citation82

Thoracic endometriosis syndrome

Thoracic endometriosis syndrome is an unusual entity consisting of endometriosis of the lung parenchyma, airways, or pleura (). Thoracic endometriosis generally consists of one of four manifestations, in order of most common presentation: catamenial pneumothorax (80%), catamenial hemothorax (14%), catamenial hemoptysis (5%), and endometriotic lung nodules.Citation73,Citation79,Citation83 Most thoracic lesions are solitary with the right hemithorax involved in 92% of cases, the left hemithorax in 5%, and both in 3%.Citation79,Citation84 Among patients with thoracic endometriosis, 50%–80% will also have disease of the pelvis.Citation83 Catamenial pneumothorax is defined as pneumothorax occurring within 72 hours of onset of menses. Although often cyclic, recurrences may occur in the premenstrual period or at time of ovulation.Citation79 It is possible that many cases of presumed primary pneumothorax in women are actually due to thoracic endometriosis. Patients with thoracic endometriosis usually present with nonspecific symptoms including cough, shortness of breath, chest discomfort, and less commonly, hemoptysis. They may also experience referred pain to the shoulder, neck, or scapula due to diaphragmatic irritation.

The most important tool for the diagnosis of thoracic endometriosis syndrome is astute clinical suspicion. Emergent cases of catamenial pneumothorax or hemothorax are managed with thoracentesis and chest tube. Medical management for catamenial symptoms, particularly gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, may be both diagnostic and therapeutic.Citation85 A catamenial pattern of symptoms is considered pathognomonic for the disease. CT, MRI, chest radiograph, and bronchoscopy may be useful in evaluation, primarily to rule out malignancy, infection, or other pathology, although they have low yield for diagnosis of endometriosis.Citation86 Bronchoscopy-directed biopsy rarely confirms endometriosis, but brush cytology more frequently confirms the presence of endometrial cells.Citation79 Definitive diagnosis and surgical treatment of thoracic endometriosis syndrome is accomplished with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS).Citation87 A multidisciplinary approach with VATS in combination with VALS will reveal disease of the thoracic cavity and subdiaphragmatic surface as well as the pelvis.Citation85,Citation88–Citation90 In a multidisciplinary approach with experienced cardiothoracic and gynecologic surgeons, thoracic and diaphragmatic endometriosis can be treated with laser ablation of lesions or with resection and repair of the diaphragm, pleura, or lung.Citation84,Citation86,Citation90

Other sites of extrapelvic endometriosis

Endometriosis has been found in nearly every organ of the body. Endometriosis of the abdominal diaphragm may present with similar discomfort as that of the thoracic diaphragm. It is more likely to be found on the right side due to the natural clockwise flow of peritoneal fluid.Citation79 Pain is most commonly in the right upper quadrant, right chest or shoulder, or right scapula. Again, a multidisciplinary approach is sensible, as resection of lesions may require repair of the diaphragm.

Endometriosis of the liver and omentum are less common but should be kept in mind when performing diagnostic or operative VALS. Liver endometriosis may present with right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, malaise, nausea, vomiting, obstructive jaundice, portal vein thrombosis, and hepatomegaly.Citation79,Citation91 Malignant transformation is a concern in the liver as in any unusual location of endometriosis, although the ovary is the most common site for endometriosis-associated malignancy to occur.Citation92,Citation93

Endometriosis has also been found in muscle, bone, nerves, the pancreas, and the kidney. Endometriosis of the vagina and cervix may be detected on physical exam. Symptoms include pain, dyspareunia, postcoital bleeding, metrorrhagia, or a palpable mass. Vulvar, perineal, and perianal endometriosis generally occurs in episiotomy, laceration repairs, or other vulvar scars. Lesions of the vagina, cervix, or vulva should be biopsied to exclude malignant or premalignant conditions.

Particularly with cutaneous incidence of endometriosis, fine needle aspiration is showing significant promise for cytopathologic diagnosis and serves to facilitate planning for surgical management.Citation94

Postoperative management

Following laparoscopic surgery for diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis, most patients may be discharged home on the same day.

A comprehensive discussion of surgical and medical management of endometriosis is beyond the scope of this review. However, provided that endometriosis is recognized upon laparoscopic exploration, every reasonable attempt should be made to fully excise endometrial implants while remaining safely within the surgeon’s capabilities. Alternatively, referral to a more experienced surgeon may be indicated in very difficult cases.

Unless pregnancy is immediately planned, surgical resection of endometriosis should be followed by medical suppression. GnRH agonists, oral contraceptives, and progestins are among the effective options for preventing recurrence of the disease. Some patients will require repeat surgical management due to pain or infertility resulting from recurrent disease despite suppression. Patients with histologic diagnosis of endometriomas and recurrent asymptomatic cysts may be expectantly managed with physical exam and ultrasound every 6 months for 1–2 years followed by annual exam and ultrasound.Citation45 With development of symptoms, enlargement, or increase in complexity of the cysts, surgical intervention is required.

Complications

Complications of laparoscopy have become increasingly less common, occurring in 3.2 per 1000 cases.Citation95 Multiple studies have illustrated that increased surgeon experience is associated with decreased rates of complications as well as improved outcomes.Citation96,Citation97

One-third to one-half of injuries occur at entry.Citation96,Citation97 Closed entry with a Veress needle, direct entry, and open entry are all associated with same rates of vascular and bowel injury. Citation98 The astute surgeon should be familiar with all three techniques and employ the method most appropriate for the patient. Entry should occur with the patient table low and flat, as entry in Trendelenburg increases the risk of aortic or iliac vessel injury.Citation99 A left upper quadrant entry may be considered in patients suspected of having intra-abdominal adhesions. Regardless of entry technique, the area below and surrounding the site of entry should be immediately examined with the laparoscope before any further evaluation is done and before the patient is moved, to ensure that no injury has occurred.

Morbidity and mortality are extremely high for vascular injury.Citation100 The most likely sites of internal vascular injury in gynecologic laparoscopy include the aorta, inferior vena cava, and right iliac vessels. Most injuries occur during trocar placement, followed by Veress entry and electrosurgical instruments.Citation97,Citation101 Additionally, extensive retroperitoneal dissection, lymphadenectomy, and sacral colpopexy increase the risk of vascular injury.Citation101 The inferior epigastric vessels are frequently injured during lateral trocar placement.Citation100 This may be avoided with careful transillumination of the abdominal wall and mapping of the vessel course laparoscopically prior to port placement. Vessel injury should be suspected in any patient who suddenly becomes unstable intraoperatively. A retroperitoneal vessel injury may not be immediately obvious. When the site of injury is identified, pressure should be applied to minimize blood loss. The assistance of a vascular surgeon, if available, should be immediately requested. Emergency laparotomy is indicated in the event of large vessel injury.

Bowel injuries account for approximately 20% of all injuries in gynecologic laparoscopy.Citation96,Citation97 Mortality associated with delayed diagnosis of bowel injury may be up to 28%.Citation101 Approximately half of all injuries occur during entry. Injury to the stomach may be avoided by ensuring that the stomach is decompressed with a naso- or orogastric tube prior to entry. Management of a bowel injury recognized at time of laparoscopy depends on the site and extent of injury.

Bladder and ureteral injuries occur in 0.03%–0.13% of all gynecologic laparoscopies, with bladder injuries being more common.Citation96 Bladder injury most often occurs during suprapubic trocar placement and during dissection of the vesicocervical junction during hysterectomy. The authors prefer to place the suprapubic port 4 cm superiorly to the pubic symphysis, instead of the more commonly used 2-cm distance. Suspected bladder injury may be confirmed by backfilling the bladder with indigo carmine. Ureteral injury is more likely to be unrecognized during surgery, particularly thermal injury in which ureteral necrosis may be delayed.Citation100,Citation102 Intravenous indigo carmine may allow the ureters to be more readily visible during laparoscopy, and spillage of the dye indicates injury. Additionally, the authors perform cystoscopy in all cases in which dissection occurred near a ureter. Minor bladder injuries are easily repaired with absorbable suture and Foley drainage. More extensive injury to the bladder or ureters should prompt urologic consultation.

Neurologic injury in laparoscopy is most commonly the result of positioning.Citation100 Patients in prolonged Trendelenburg or in surgeries lasting more than 4 hours in which the legs are frequently moved up and down are at highest risk of neurologic injury. The most commonly involved nerves affecting the lower extremities are the femoral, sciatic, and peroneal nerves, and injury results from hyperflexion or excessive external hip rotation, or compression at the lateral knee. Upper extremity neurologic injury may occur due to prolonged Trendelenburg position with shoulder braces, hyperextension of the shoulders, or compression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. Treatment of iatrogenic neuropathy is typically supportive, and most injuries will resolve with time. However, neurologic and physical therapy consultation should be considered depending on the extent of apparent injury.

Electrosurgery in laparoscopy is a common cause of injury, and surgeons must be familiar with their electrosurgical instruments, their safe use, and their risks. Electrosurgical injury may occur when an instrument is inadvertently activated when out of the visual field. Direct coupling, in which a current is diverted from the instrument to another metal instrument may also cause injury.Citation103 Capacitive coupling with monopolar energy occurs when the energy from an active electrode is passed through the insulating sheath to another conductive device. This risk is most concerning with a combination metal and plastic trocar but may also occur with an all-plastic trocar. An allmetal trocar allows the energy to safely disperse through the abdominal wall. Electrosurgical injuries are increased with the use of higher voltage waveforms. Therefore, the use of a ‘cut’ setting is preferred over ‘coagulation’ wherever possible.

Finally, the use of CO2 insufflation carries risks as well, including subcutaneous emphysema, pneumothorax, and gas embolization.Citation100 Careful entry and ensuring that trocars do not slip into the pre-peritoneal space will help to prevent subcutaneous emphysema, which is most often self-limited. Pneumothorax is readily identified by chest radiograph and should be suspected in patients with chest pain and shortness of breath following laparoscopy. Gas embolization is exceedingly rare but may be devastating. A precipitous drop in the patient’s oxygen saturation and/or end-tidal CO2 or premature ventricular contractions should prompt cessation of the procedure and placement of the patient in left lateral decubitus position with airway and vascular support.

Conclusion

Endometriosis is a highly complex disease with varying presentations. A high index of suspicion is the first and foremost tool of the wise diagnostician. For abdominal and pelvic disease, video-assisted laparoscopic surgery is not only preferable but has also become the standard of care due to decreased morbidity when compared with laparotomy. When extragenital or extensive disease is suspected, a multidisciplinary approach is preferred. Complications of laparoscopy may be mitigated with increased surgeon experience and careful attention to surgical detail.

Disclosures

The fellowship for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery received an educational grant from Plasma Surgical®.

References

- GiudiceLCKaoLCEndometriosisLancet20043641789179915541453

- BalaschJCreusMFabreguesFVisible and non-visible endometriosis at laparoscopy in fertile and infertile women and in patients with chronic pelvic pain: a prospective studyHum Reprod1996113873918671229

- MartinJDJrHauckAEEndometriosis in the maleAm Surg1985514264304014886

- ValleRFSciarraJJEndometriosis: treatment strategiesAnn N Y Acad Sci200399722923914644830

- LoboREndometriosis: Etiology, Pathology, Diagnosis and Management5th edKatzVLComprehensive GynecologyPhiladelphia, PAMosby Elsevier2007473499

- SimpsonJLEliasSMalinakLRButtramVCJrHeritable aspects of endometriosis. I. Genetic studiesAm J Obstet Gynecol19801373273317377252

- SchipperENezhatCEndometriosis and LeiomyomaWorld Clin Obstet Gynecol www.amazon.co.uk/Clinics-Obstetrics-Gynecology-Endometriosis-Volume/dp/935035800520111164177

- HuangJQLathiRBLemyreMRodriguezHENezhatCHNezhatCCoexistence of endometriosis in women with symptomatic leiomyomasFertil Steril20109472072319393995

- UimariOJarvelaIRyynanenMDo symptomatic endometriosis and uterine fibroids appear together?J Hum Reprod Sci20114343821772738

- Practice bulletin no. 114: management of endometriosisObstet Gynecol201011622323620567196

- KennedySBergqvistAChapronCESHRE guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosisHum Reprod2005202698270415980014

- Van HolsbekeCVan CalsterBGuerrieroSEndometriomas: their ultrasound characteristicsUltrasound Obstet Gynecol20103573074020503240

- GhezziFRaioLCromiA“Kissing ovaries”: a sonographic sign of moderate to severe endometriosisFertil Steril20058314314715652900

- MooreJCopleySMorrisJLindsellDGoldingSKennedySA systematic review of the accuracy of ultrasound in the diagnosis of endometriosisUltrasound Obstet Gynecol20022063063412493057

- KruseCSeyer-HansenMFormanADiagnosis and treatment of rectovaginal endometriosis: An overviewActa Obstet Gynecol Scand2012 [Epub ahead of print.]

- BiscaldiEFerreroSFulcheriERagniNRemorgidaVRollandiGAMultislice CT enteroclysis in the diagnosis of bowel endometriosisEur Radiol20071721121916937103

- NezhatCRNezhatFAdmonDSeidmanDNezhatCHLaparoscopic Management of Genitourinary EndometriosisJ Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc19941S25

- ChamieLPBlasbalgRPereiraRMWarmbrandGSerafiniPCFindings of pelvic endometriosis at transvaginal US, MR imaging, and laparoscopyRadiographics201131E77E10021768230

- LandiSBarbieriFFiaccaventoAPreoperative double-contrast barium enema in patients with suspected intestinal endometriosisJ Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc20041122322815200779

- FaccioliNManfrediRMainardiPBarium enema evaluation of colonic involvement in endometriosisAJR Am J Roentgenol20081901050105418356454

- FaccioliNFotiGManfrediREvaluation of colonic involvement in endometriosis: double-contrast barium enema vs magnetic resonance imagingAbdom Imaging20103541442119568808

- RoseauGDumontierIPalazzoLRectosigmoid endometriosis: endoscopic ultrasound features and clinical implicationsEndoscopy20003252553010917184

- SquiffletJFegerCDonnezJDiagnosis and imaging of adenomyotic disease of the retroperitoneal spaceGynecol Obstet Invest200254Suppl 1435112441660

- MayKEConduit-HulbertSAVillarJKirtleySKennedySHBeckerCMPeripheral biomarkers of endometriosis: a systematic reviewHum Reprod Update20101665167420462942

- Al-JefoutMDezarnauldsGCooperMDiagnosis of endometriosis by detection of nerve fibres in an endometrial biopsy: a double blind studyHum Reprod2009243019302419690352

- BokorAKyamaCMVercruysseLDensity of small diameter sensory nerve fibres in endometrium: a semi-invasive diagnostic test for minimal to mild endometriosisHum Reprod2009243025303219690351

- BerkerBHLeeKNezhatCNezhatFNezhatCLaparoscopic Treatment of EndometriosisCamran NezhatFNNezhatCeananNezhat’s Operative Gynecologic Laparoscopy and HysteroscopyNew YorkCambridge University Press2008263303

- KelleyWEJrThe evolution of laparoscopy and the revolution in surgery in the decade of the 1990sJSLS20081235135719275847

- PalmerRGynecological celioscopy; its possibilities and present indicationsSem Hop19543044404443 French13225846

- PappasTNJacobsDOLaparoscopic resection for colon cancer – the end of the beginning?N Engl J Med20043502091209215141049

- PageBCamran Nezhat and the Advent of Advanced Operative Video-laparoscopyNezhatCNezhat’s History of EndoscopyTuttlingen, GermanyEndo:Press2011159187

- NezhatCCrowgeySRGarrisonCPSurgical treatment of endometriosis via laser laparoscopyFertil Steril1986457787832940121

- NezhatCCrowgeySRGarrisonCPSurgical treatment of endometriosis via laser laparoscopy and videolaseroscopyContrib Gynecol Obstet1987163033122961509

- NezhatCNezhatFOperative laparoscopy (minimally invasive surgery): state of the artJ Gynecol Surg1992811114110171579

- VilosGATernamianADempsterJLabergePYThe Society of Obstetricians Gynaecologists of CanadaLaparoscopic entry: a review of techniques, technologies, and complicationsJ Obstet Gynaecol Can20072943346517493376

- NezhatCRNezhatFRSilfenSLVideolaseroscopy. The CO2 laser for advanced operative laparoscopyObstet Gynecol Clin North Am1991185856041835530

- BatemanBGKolpLAMillsSEndoscopic versus laparotomy management of endometriomasFertil Steril1994626906957926074

- CatalanoGFMaranaRCaruanaPMuziiLMancusoSLaparoscopy versus microsurgery by laparotomy for excision of ovarian cysts in patients with moderate or severe endometriosisJ Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc199632672709050638

- CrosignaniPGVercelliniPBiffignandiFCostantiniWCortesiIImparatoELaparoscopy versus laparotomy in conservative surgical treatment for severe endometriosisFertil Steril1996667067118893671

- BusaccaMFedeleLBianchiSSurgical treatment of recurrent endometriosis: laparotomy versus laparoscopyHum Reprod199813227122749756309

- AdamsonGDSubakLLPastaDJHurdSJvon FranqueORodriguezBDComparison of CO2 laser laparoscopy with laparotomy for treatment of endometriomataFertil Steril1992579659731533375

- MaisVAjossaSGuerrieroSLaparoscopic management of endometriomas: a randomized trial versus laparotomyJ Gynecol Surg1996124146

- BusaccaMVignaliMEndometrioma excision and ovarian reserve: a dangerous relationJ Minim Invasive Gynecol20091614214819249702

- SchipperENezhatCEndometriomasWorld Clin Obstet Gynecol www.amazon.co.uk/Clinics-Obstetrics-Gynecology-Endometriosis-Volume/dp/935035800520111137142

- MartinATorrentALaparoscopic nerve-sparing radical trachelectomy: surgical technique and outcomeJ Minim Invasive Gynecol201017374120129330

- PossoverMStoberSPlaulKSchneiderAIdentification and preservation of the motoric innervation of the bladder in radical hysterectomy type IIIGynecol Oncol20007915415711063637

- DemirBSenerbahceZGuzelAIDemirSKilincNAbdominal wall endometriosis following cesarean section: report of five casesClin Exp Obstet Gynecol20113828829021995169

- LipscombGHGivensVMSmithWEEndometrioma occurring in abdominal wall incisions after cesarean sectionJ Reprod Med201156444621366126

- BerkerBLashayNDavarpanahRMarzialiMNezhatCHNezhatCLaparoscopic appendectomy in patients with endometriosisJ Minim Invasive Gynecol20051220620915922976

- StegmannBJSinaiiNLiuSUsing location, color, size, and depth to characterize and identify endometriosis lesions in a cohort of 133 womenFertil Steril2008891632163617662280

- NezhatCNezhatFRSafe laser endoscopic excision or vaporization of peritoneal endometriosisFertil Steril1989521491512526028

- NezhatCHoodJWinerWNexhatFCrowgeySRGarrisonCPVideolaseroscopy and laser laparoscopy in gynaecologyBr J Hosp Med1987382192242960410

- NezhatCKhoKAMorozovVUse of neutral argon plasma in the laparoscopic treatment of endometriosisJSLS20091347948320202387

- VercelliniPEndometriosis: what a pain it isSemin Reprod Endocrinol1997152512619383834

- ArenasAKJBDonald School Textbook of Transvaginal SonographyNew Delhi, IndiaJaypee Brothers Medical Publishers2005

- NezhatFDattaMSHansonVPejovicTNezhatCThe relationship of endometriosis and ovarian malignancy: a reviewFertil Steril2008901559157018993168

- Van GorpTAmantFNevenPVergoteIMoermanPEndometriosis and the development of malignant tumours of the pelvis. A review of literatureBest Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol20041834937115157647

- NezhatCHajhosseiniBKingLPRobotic-assisted laparoscopic treatment of bowel, bladder, and ureteral endometriosisJSLS20111538739221985730

- NezhatCLewisMKotikelaSVeeraswamyASaadatLHajhosseiniBRobotic versus standard laparoscopy for the treatment of endometriosisFertil Steril2010942758276020537632

- ErcoliAD’AstaMFagottiARobotic treatment of colorectal endometriosis: technique, feasibility and short-term resultsHum Reprod20122772272622238113

- Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996Fertil Steril1997678178219130884

- KimJYKwonJEKimHJParkKFine-needle aspiration cytology of abdominal wall endometriosis: A Study of 10 CasesDiagn Cytopathol2011 [Epub ahead of print.]

- GuptaRKFine-needle aspiration cytodiagnosis of endometriosis in cesarean section scar and rectus sheath mass lesions – a study of seven casesDiagn Cytopathol20083622422618335552

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive MedicineEndometriosis and infertilityFertil Steril200686S156S16017055813

- BattRESmithRAEmbryologic theory of histogenesis of endometriosis in peritoneal pocketsObstet Gynecol Clin North Am19891615282664615

- AdamyanLAdditional international perspectivesNicholsDGynecologic Obstetric SurgerySt Louis, MOMosby Year Book199311671182

- ChapronCFauconnierAVieiraMAnatomical distribution of deeply infiltrating endometriosis: surgical implications and proposition for a classificationHum Reprod20031815716112525459

- HaasDChvatalRHabelsbergerAWurmPSchimettaWOppeltPComparison of revised American Fertility Society and ENZIAN staging: a critical evaluation of classifications of endometriosis on the basis of our patient populationFertil Steril2011951574157821315335

- AdamsonGDPastaDJEndometriosis fertility index: the new, validated endometriosis staging systemFertil Steril2010941609161519931076

- AdamsonGDEndometriosis classification: an updateCurr Opin Obstet Gynecol20112321322021666464

- Ad hoc Committees: Endometriosis Classification2011 Available at: www.aagl.org/Committees-Ad-Hoc:Accessed April 14, 2012

- CocciaMERizzelloFUltrasonographic staging: a new staging system for deep endometriosisAnn N Y Acad Sci20111221616921401631

- DouglasCRotimiOExtragenital endometriosis – a clinicopathological review of a Glasgow hospital experience with case illustrationsJ Obstet Gynaecol20042480480815763794

- NezhatFNezhatCPenningtonEAmbrozeWJrLaparoscopic segmental resection for infiltrating endometriosis of the rectosigmoid colon: a preliminary reportSurg Laparosc Endosc199222122161341533

- NezhatCNezhatFPenningtonELaparoscopic treatment of infiltrative rectosigmoid colon and rectovaginal septum endometriosis by the technique of videolaparoscopy and the CO2 laserBr J Obstet Gynaecol1992996646671390472

- NezhatCPenningtonENezhatFSilfenSLLaparoscopically assisted anterior rectal wall resection and reanastomosis for deeply infiltrating endometriosisSurg Laparosc Endosc199111061081669382

- NezhatCNezhatFPenningtonENezhatCHAmbrozeWLaparoscopic disk excision and primary repair of the anterior rectal wall for the treatment of full-thickness bowel endometriosisSurg Endosc199486826858059307

- NezhatFNezhatCPenningtonELaparoscopic proctectomy for infiltrating endometriosis of the rectumFertil Steril199257112911321533374

- VeeraswamyALewisMMannAKotikelaSHajhosseiniBNezhatCExtragenital endometriosisClin Obstet Gynecol20105344946620436322

- NezhatCHMalikSOsiasJNezhatFNezhatCLaparoscopic management of 15 patients with infiltrating endometriosis of the bladder and a case of primary intravesical endometrioid adenosarcomaFertil Steril20027887287512372471

- NezhatCRNezhatFRLaparoscopic segmental bladder resection for endometriosis: a report of two casesObstet Gynecol1993818828848469507

- NezhatCNezhatFGreenBLaparoscopic treatment of obstructed ureter due to endometriosis by resection and ureteroureterostomy: a case reportJ Urol19921488658681387420

- JosephJSahnSAThoracic endometriosis syndrome: new observations from an analysis of 110 casesAm J Med19961001641708629650

- KoromSCanyurtHMissbachACatamenial pneumothorax revisited: clinical approach and systematic review of the literatureJ Thorac Cardiovasc Surg200412850250815457149

- AlifanoMRothTBroetSCSchusslerOMagdeleinatPRegnardJFCatamenial pneumothorax: a prospective studyChest20031241004100812970030

- HilarisGEPayneCKOsiasJCannonWNezhatCRSynchronous rectovaginal, urinary bladder, and pulmonary endometriosisJSLS20059788215791976

- BaganPLe Pimpec BarthesFAssouadJSouilamasRRiquetMCatamenial pneumothorax: retrospective study of surgical treatmentAnn Thorac Surg20037537881 discusssion 8112607643

- NezhatFNezhatCLevyJSLaparoscopic treatment of symptomatic diaphragmatic endometriosis: a case reportFertil Steril1992586146161387851

- NezhatCNicollLMBhaganLEndometriosis of the diaphragm: four cases treated with a combination of laparoscopy and thoracoscopyJ Minim Invasive Gynecol20091657358019835800

- NezhatCSeidmanDSNezhatFLaparoscopic surgical management of diaphragmatic endometriosisFertil Steril199869104810559627291

- NezhatCKazerooniTBerkerBLashayNFernandezSMarzialiMLaparoscopic management of hepatic endometriosis: report of two cases and review of the literatureJ Minim Invasive Gynecol20051219620015922974

- ChoJENezhatFRRobotics and gynecologic oncology: review of the literatureJ Minim Invasive Gynecol20091666968119896593

- KhanAWCraigMJarmulowiczMDavidsonBRLiver tumours due to endometriosis and endometrial stromal sarcomaHPB (Oxford)20024434518333152

- FernandesHMarlaNJPailoorKKiniRPrimary umbilical endometriosis – Diagnosis by fine needle aspirationJ Cytol20112821421622090700

- ChapronCFauconnierAGoffinetFBréartGDubuissonJBLaparoscopic surgery is not inherently dangerous for patients presenting with benign gynaecologic pathology. Results of a meta-analysisHum Reprod2002171334134211980761

- ChapronCQuerleuDBruhatMASurgical complications of diagnostic and operative gynaecological laparoscopy: a series of 29,966 casesHum Reprod1998138678729619539

- JansenFWKapiteynKTrimbos-KemperTHermansJTrimbosJBComplications of laparoscopy: a prospective multicentre observational studyBr J Obstet Gynaecol19971045956009166204

- AhmadGO’FlynnHDuffyJMPhillipsKWatsonALaparoscopic entry techniquesCochrane Database Syst Rev20122CD00658322336819

- NezhatFBrillAINezhatCHNezhatASeidmanDSNezhatCLaparoscopic appraisal of the anatomic relationship of the umbilicus to the aortic bifurcationJ Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc199851351409564060

- MakaiGIsaacsonKComplications of gynecologic laparoscopyClin Obstet Gynecol20095240141119661756

- ChapronCMPierreFLacroixSQuerleuDLansacJDubuissonJBMajor vascular injuries during gynecologic laparoscopyJ Am Coll Surg19971854614659358090

- Harkki-SirenPKurkiTA nationwide analysis of laparoscopic complicationsObstet Gynecol1997891081128990449

- BrillAIElectrosurgery: principles and practice to reduce risk and maximize efficacyObstet Gynecol Clin North Am20113868770222134017