Abstract

Uterine prolapse is a major reproductive health issue in Nepal. There is a wide range of literature available on the causes and risk factors of uterine prolapse and on the ways to prevent and treat it. There is still a lack of published evidence on what prevention and treatment services are working well or the attitudes toward them. This paper presents the findings of a qualitative study on primary and secondary prevention of uterine prolapse in Eastern Nepal.

Method

The study involved eight focus group discussions with 71 women in six villages of the eastern districts of Siraha and Saptari and 14 qualitative interviews with health professionals from the local to central level. The group discussions and interviews covered the awareness levels of uterine prolapse and its prevention and treatment, as well as participants’ opinions on and experiences with the services offered.

Results

It was found that patriarchy, gender discrimination, and cultural traditions such as early marriage and pregnancy make it difficult for people to discontinue uterine prolapse risk behaviors. Women are aware of risk factors, prevention, and treatment, but are powerless to change their situations. Health professionals and women are fond of surgery as treatment, but opinions on the use of ring pessaries and pelvic floor muscle training are split.

Conclusion

The main recommendation that can be drawn from this study is that research on the effectiveness of early treatments, such as ring pessaries and exercise, should be conducted. Furthermore, the involvement of other target groups (husbands, adolescents, and mothers-in-law) needs to be increased in order to make it easier for women to adapt low-risk behaviors. Finally, uterine prolapse prevention should be better integrated in national reproductive health services. Enforcing transparency, monitoring systems, and collaborations are important factors that should be considered as well.

Introduction

Uterine prolapse is a reproductive health condition that has not received sufficient attention despite its high prevalence. Furthermore, it seems that uterine prolapse not only affects older women but is also very common among younger women.Citation1

Based on many cross-sectional studies conducted on a community or clinical basis, the prevalence of uterine prolapse among women in Nepal varies somewhere between 10% and 37%.Citation2–Citation4 Other sources mention that an estimated number of 600,000 women in Nepal suffer from uterine prolapse, with about one third requiring immediate surgical treatment.Citation5 However, the actual number is assumed to be higher since only women in the reproductive age group (15–49) were included in the study. Currently, the availability of services for uterine prolapse is increasing, and more women are becoming aware of the issue and are seeking help instead of keeping their prolapse a secret. Causes and risk factors for uterine prolapse are complex and deeply embedded in the cultural, economic, and social conditions of women. They range from early marriage and childbirth to malnutrition, work overload, and lack of rest in the pre and postnatal period. Furthermore, there is a lack of knowledge and access to antenatal medical care.Citation4,Citation6 Next to the obvious physical consequences (difficulties when doing daily work, infections, and pain), uterine prolapse can also trigger psycho-social problems. Emotional isolation, risk of violence and discrimination, and facing social stigma are only some such problems.Citation7 Preventing uterine prolapse requires awareness raising and behavior changes at the individual, family, and community levels (primary prevention). Women’s health is strongly connected to gender devaluation, especially because of the high levels of maternal malnutrition and son preference, which lead to early and multiple births at short intervals.Citation8 There are different ways to treat a prolapse and to prevent it from worsening. First and second degree prolapse can be stopped/treated through the use of ring pessaries, often in combination with pelvic floor exercises (secondary prevention). Third degree prolapse requires surgical treatment (tertiary prevention), which is of limited availability and is cost prohibitive in a low-income country such as Nepal.Citation9

Nepalese women and reproductive health

The magnitude of women’s reproductive health problems in developing countries is enormous.Citation3 Females are discriminated against from early childhood, and this discrimination continues into their adult reproductive years and beyond. Such discrimination complicates women’s right to make independent decisions regarding health or family planning, such as preventing unwanted pregnancies.Citation10 As “easy” as it may be to collect and identify mortality data, it is difficult to identify information about morbidities in general and about maternal morbidities more specifically. Studying gynecological morbidities is challenging since these issues are considered a taboo topic in Nepal, which makes talking about it very difficult.Citation11

Nepal is a patriarchal society and all institutions – ranging from education to the legal system and even health services – are strongly influenced by these norms and values. Generally, Nepalese women have three main responsibilities: reproduction and child bearing, household maintenance, and income earning. In rural areas, the women’s work burden is considered to be 12%–22% greater than the men’s, and these women must work hard in order to gain acceptance in their husbands’ homes.Citation12

This paper presents findings from a qualitative community assessment of primary and secondary prevention of uterine prolapse in Eastern Nepal. The aim of this research was to determine the status of uterine prolapse prevention in Eastern Nepal by looking at the availability of services and by identifying the uterine prolapse prevention awareness levels, attitudes, and experiences of both service providers and women. Fieldwork was conducted in 2011 and was supported by the Women’s Reproductive Rights Program (WRRP), a national non-governmental organization.

The findings should contribute to the existing research and fill in the gaps in relation to qualitative research on the issue. The study setting was the Kathmandu area for qualitative interviews and the two eastern districts of Siraha and Saptari for the qualitative interviews and focus group discussions. These districts were chosen based on a 2006 household survey conducted by the WRRP among 10% of all households in Siraha and Saptari. The survey showed a uterine prolapse prevalence of 30% in Siraha and 42% in Saptari. The respondents in that survey were married women between the ages of 16 and 60 years from different social groups.Citation4

Methods

Two different approaches were used: qualitative interviews with health service providers from different levels and focus group discussions with affected and non-affected women in the eastern districts of Siraha and Saptari.

Focus group discussions were conducted in six villages (roadside and countryside in Siraha and Saptari) with women in two different age groups (15–30 and 30 plus) and those affected or not affected by uterine prolapse (). The villages were chosen based on the fact that these women had not previously participated in any kind of qualitative research. Focus group participants were recruited according to convenience sampling with the help of female campaigners, hired by the WRRP, who were members of the community raising awareness on uterine prolapse. They recommended those they knew who fit the criteria (village, age, and uterine prolapse). A total of 71 women participated in eight focus group discussions. The fact that the WRRP has been working in these areas for many years was a valuable advantage. Their activities and field workers are known by the people in the area, and more important, they are trusted by the people. Therefore, women did not feel shy about talking during the group discussions. See for an example of a focus group discussion.

Table 1 Focus group discussion participants

Health professionals and service providers were asked to participate in individual qualitative interviews. These 14 key informants were men and women, who were included under the condition that they were currently working on the issue of uterine prolapse (see ). The methodological approach used attempted to reach a point of saturation in the data. This means data were collected until no new insights were collected.

Table 2 Qualitative interview participants

Questions asked in the focus group discussions and qualitative interviews were similar, but were more detailed in the individual interviews. The topics discussed included awareness and knowledge of uterine prolapse, its causes, and risk factors as well as methods to prevent and treat it. Furthermore, people were asked about their opinions on, and experiences with, prevention and treatment services.

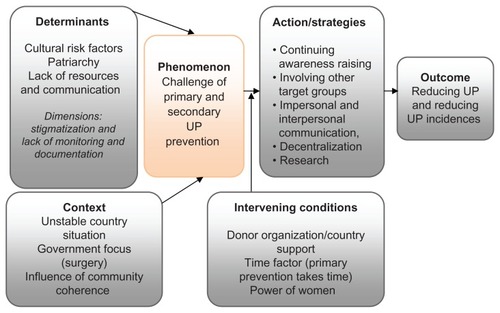

The data from the health professionals were combined with the “consumer” perspective of the women in the analysis, which was based on grounded theory methods.Citation13,Citation14 In the first round of coding, data were categorized and broken down into their smallest fragments (open line-by-line coding). However, all possible theoretical directions were kept open. In the next step, the data were reassembled and links between categories were identified (axial coding). According to the paradigm model, concepts were built to define categories in the data (phenomena). Based on these phenomena, corresponding categories were defined (causal conditions, context, intervening conditions, action/ interaction, and consequences). shows a pathway model including all the major phenomena found in the data and is the basis for further analysis and discussion. These detailed phenomena were categorized again into the four main issues presented below.

Figure 2 A pathway model of uterine prolapse prevention and treatment according to the study results.

Abbreviation: UP, uterine prolapse.

Results

Culture and uterine prolapse

Among others, cultural traditions were mentioned as risk factors for uterine prolapse in almost every interaction with both women and health professionals, starting with the heavy workload women are exposed to and the so called “triple burden” (household duties, field and cattle work, and reproductive role): “We don’t have time. We rest when we are washing our hands after doing the dishes and only death will stop the workload” (focus group discussion [FGD], woman).

Early pregnancy due to child marriage and the pressure to give birth to a son are further cultural risk factors that seem to have a tremendous influence on the occurrence of uterine prolapse. Girls are married in order to avoid love scandals and because they are needed by their families-in-law for their ability to work: “Only a few days after giving birth, they have to start their household work again. It includes all – also carrying the heavy loads. They have to fetch water from far away ponds and bring home grass for the cattle. It is very normal to work hard again very soon after having a baby” (interview, morbidity officer).

Awareness levels regarding uterine prolapse are rising. One example for this is the increasing awareness among women about the danger of after-birth practices, such as stomach massages in which they attempt to force out “bad” things. (The post-delivery contracted uterus feels like a foreign body from the outside.) On the other hand, reduced or special diets after pregnancy are still common in some parts of Nepal: “We did not know that it is good to eat saag (spinach) after pregnancy. We thought the bad thing (afterbirth) [would] not come out or the baby [would] turn green. That is why they don’t give us saag to eat” (FGD, woman).

However, due to awareness raising projects regarding uterine prolapse prevention and treatment possibilities, women’s knowledge on the risk factors has been increasing recently. Street dramas and other kinds of mass media, such as wall paintings or hoarding boards in public spaces, are popular strategies to depict memorable and authentic everyday situations. Younger people see these activities as entertaining and educational, whereas it seems that the older generation ignores the information. While belief in these traditions is decreasing, health professionals still complain about difficulties in breaking through these cultural walls.

Nepal has a patriarchic social system in which the man is the head of the family and the decision maker. Women are discriminated against and they accept not having any privacy, freedom, decision-making power, or financial independence because they fear conflicts, punishment, or even being replaced by a new wife. Men do not seem to feel responsible for the reproductive health status of the woman. Women are only accepted by their husbands, family, and society after giving birth to a boy: “They [men] say, ‘I don’t care if you live or die. It is about the sons!’ Look at this woman here. She has three daughters and no son. She has a prolapse and is in deep trouble. The family understands the problem, but they want a son anyway” (FGD, woman).

The target group “husband” is becoming more important for health professionals and service providers. Even if women know the risk factors of uterine prolapse and how to avoid them, it is the husband’s support that is needed from the start. Discussing a sensitive issue like uterine prolapse with men is very difficult, especially when this is being done by female service providers in a patriarchal society: “We need to change the husbands in Siraha, and at the same time, men at all levels – also the political parties. They have to understand and internalize this problem of their wives” (interview, sociologist).

Family, society, and stigmatization

Family and in-laws play an important role in the prevention of uterine prolapse, and their understanding and support is connected to the attitudes of the community. If uterine prolapse is highly stigmatized in the community, the family hesitates to engage in preventive activities. If, however, the community is aware of the issue, it is easier for husbands and families to make steps in the right direction.

One person often mentioned by local health workers is the mother-in-law. After many years under male domination, a mother-in-law has accepted her subordinate role and maintains traditional values. Even though mothers-in-law are women themselves and do have a certain amount of power in the family, not all daughters-in-law can expect support from them. On the contrary, mothers-in-law claim that when they were younger, they had to work even harder than do their daughters-in-law and that uterine prolapse was a part of their lives. Next to the husband, the mother-in-law seems to be the other important key member in families needed to support the health situation of younger women. An increasing number of awareness raising campaigns are showing positive results: “There are some mothers-in-law who understand. She doesn’t want her daughter-in-law to suffer the same [way she did]. But this is only one in 100” (FGD, woman).

Family interaction and open communication are two things repeatedly mentioned as effective methods within prolapse prevention. While mass media methods reach the whole community, door-to-door visits by local health workers are a method of approaching families regarding uterine prolapse from a more intimate angle. Approaching men, however, remains a challenge.

Everything connected to sexuality is a taboo issue in Nepal and everything around uterine prolapse is, despite increasing awareness, still highly stigmatized. Women with a prolapse consider themselves lost. They cannot fulfill their daily routines, and in the worst case, they are treated as outcasts in their family and society: “They think that when a woman has a prolapse, it is because she is bad. It is her destiny or because she is punished by God for her sins” (interview, community health worker).

Preventive work is challenging because uterine prolapse is a social taboo. Moreover, in Nepal, information and treatment cannot be accessed by everyone. Approaching groups is considered as an effective way to improve the flow of information on the prevention and treatment of a prolapse – under the condition that the groups are single sex only. Furthermore, proper integration of sexual and reproductive health issues is required by health professionals as well as the women who wish that future generations are sensitized much earlier.

Position of service providers

In order to increase knowledge and awareness among people, health professionals, and especially local health workers, education and information on the issue is needed. Many service providers reported being unable to cope with the situation when first being confronted with uterine prolapse: “I was a MCHW [maternal child health worker] and then I became an ANM [auxiliary nurse and midwife]. I [had] studied little in my course about prolapse and I had never see it with own eyes and did not know what to do. I did not know the complications or how to use ring pessaries” (interview, ANM).

Peoples level of knowledge on risk factors and consequences of uterine prolapse is increasing as well as the knowledge on the importance of including different target groups (women, husband, and community) is increasing.

Opinions on the use of ring pessaries and pelvic floor rehabilitation (exercises) are split. Besides the obvious relief a ring pessary and/or exercises can give to the woman, service providers also mention a range of drawbacks, such as hygiene and a lack of resources for high quality services. Health professionals call for more research on both ring pessaries and exercises to prove their effectiveness to aid in future policy decisions and to improve the counseling of women and their families.

Overall, health professionals learn about the importance of early prevention through information and awareness campaigns. Surgical treatments are expensive and can only reach a limited number of people. Health professionals mention overloaded staff in mobile health camps and the quality of these “mass surgeries” is yet to be seen. However, it is preventive activities and not treatment that can eliminate new cases.

Local health workers in particular complain about not getting enough training on how to handle prolapse cases. They consider knowledge and skills regarding uterine prolapse very important because they guarantee them the trust of patients and communities. In some regions, women do seem to have problems with being treated by male health workers. In other regions, women have been able to overcome their shyness and accept help from men because their pain is unbearable.

One of the main conflicts mentioned by respondents working in the public sector is created by the lack of decisionmaking power on local level. They complain about top-down approaches and suboptimal resource distributions, which decreases their motivation and commitment to work: “They [the government] give us a yearly plan we have to stick to. If we were able to make our own plans on [the] district level according to our needs, we could do more on uterine prolapse” (interview, district public health officer).

On the other hand, respondents from higher levels mention a lack of self-initiative and commitment from local health workers. They request more collaboration between ministries and also between the public sector and national and international organizations. Nongovernmental organizations and international nongovernmental organizations, however, do have more resources and can therefore react faster and more specifically, which increases the level of trust they receive from many health professionals. In the opinion of organizations, the lack of governmental awareness and the unstable political situation in Nepal complicate working on the prevention of uterine prolapse. There are some points health professionals on all levels mention:

Lack of resources

Lack of monitoring, documentation, and control

Lack of information flow, interaction, and collaboration

Unstable political situation, which makes it difficult to make long-term plans

Mutual blaming for failures

Country situation

The participants of both the qualitative interviews and the focus group discussions mentioned repeatedly the challenges associated with the unstable political situation and development status of Nepal. The lack of resources has a tremendous impact on the quality of information, goods, and services. To do something rather than nothing is not a good enough argument for insufficient prevention interventions. The availability of services is worse in the most rural parts of Nepal because they are hard to reach. The other point is that, if available, the focus is still too much on the provision of surgery rather than primary and secondary prevention: “Dependent on where they are in the country, the women don’t have optimal access to all kinds of services. Uterine prolapse is just one of them, and it is caused by a mixture of different things. Instead of working on it from a vertical project, it should be a mixture of prevention, social issues on how to prevent and treat, and the operation should be the last option” (interview, doctor).

Moreover, Nepal is a low-income country and is therefore very much dependent on international donors and programs. People who work in public health know that those with the financial power decide what prevention or treatment interventions are carried out. According to the respondents in charge of planning prevention and treatment activities, it is very difficult to find international donors willing to fund long-term Nepalese projects on uterine prolapse prevention: “I [have] experience[d] that it is a lot easier to get funds for surgery but not for prevention. The donors say it takes too long time [sic]. They cannot wait for results for many years” (interview, sociologist).

Surgical treatment interventions are easier to measure and provide quicker results and solid numbers, whereas the desired outcome of prevention programs is to see behavior change among people and a decrease of cases in future generations. In the respondents’ opinion, the focus on mortality pushes the importance of fighting morbidity into the background.

Discussion

Target groups in a patriarchal system with gender discrimination

As the data show, patriarchal structures and gender discrimination are important socio-economic determinants that influence the prevention and treatment of uterine prolapse in Nepal. The question is how can awareness among women be raised and behaviors changed if they lack decision-making power and control over their privacy, freedom, and body? The increasing number of women who are aware of how to prevent and treat uterine prolapse shows that the different awareness raising campaigns conducted over the last years have been beneficial.

Awareness is important because it creates knowledge, and having knowledge increases one’s power to speak up for one’s rights. Being informed on the causes of a prolapse counteracts risk factors that are deeply embedded in Nepalese cultural traditions, such as early marriage and pregnancy.

The findings also make clear that the strong focus on the female target group is not sufficient. Women have to consult with their husbands or other family members (eg, mother-inlaw) when making decisions. Therefore, the call for husbands as the other major target group is increasing. Unfortunately, husbands’ awareness and knowledge regarding uterine prolapse and reproductive health in general is alarmingly low. Moreover, men are difficult to approach with open communication about issues such as a prolapse, and confrontation and responsibility are often avoided by men.Citation16

During pregnancy, however, a woman seems to be much more valuable to her family because she may be carrying a son. During this time, men are more open to suggestions on how to protect their wives. Couple services or home visits by respected local health workers are more effective because they happen in the privacy of the home, and this privacy has a high priority in the life of a Nepalese family.

The best case scenario is that the man, as the main authority in the family, supports the wife in taking up low-risk and health-seeking behavior in relation to uterine prolapse. It has to be clear to him that a healthy wife has a positive effect on his own health, his offspring’s health, and the economic situation and well-being of the entire family.

Many decisions in a Nepalese family are made by the so called triad, which consists of the wife, husband, and motherin- law. It is clear that younger women do not have a lot of power against the strong opinions of husbands and mothersin- law. The role of the mother-in-law in family life has been widely underestimated. If she is aware of the causes of and methods to prevent and treat a prolapse, the mother-in-law can be a valuable support for her daughter-in-law.Citation17 If one asks why mothers-in-law are not standing up for their daughtersin- law, especially since they are women and were once in the same situation, being brought up in a patriarchal society may be the answer. It is important for mothers-in-law to recognize that the suffering they went through was avoidable, and that their support of younger women is necessary.

Culture and society: then and now

In Nepal, people have seen their grandmothers, mothers, and wives suffering from uterine prolapse throughout generations. Thus, it was seen as a natural condition that happened to women as they age. This and the fact that reproductive health issues are highly stigmatized delayed the acknowledgement of uterine prolapse as a serious female health issue that can be treated and prevented. Even when the health problem is recognized, people may not seek health care services due to fear, mistrust, or some other subjective misjudgments. For example, the acceptance of ring pessaries is increasing, but there are still women with reservations about inserting a foreign object into their bodies. The varying attitudes and experiences regarding ring pessaries create challenges when planning interventions. There is neither enough research to support or advice against the use of pessaries in the Nepalese context.

Over the last few years, many prevention campaigns using awareness raising strategies in the mass media and individual approaches have been launched. Even laws such as the minimum age for marriage (18 years) have been enacted, but without nationwide adherence and monitoring.Citation18 It is evident that the traditions and beliefs of a society cannot be changed or eradicated from one day to the next and people are still influenced by these traditions.

Therefore, much attention must be given to future and younger generations. Young people are more open to new information. Their attitudes and behaviors are not yet set. This is where sexual and reproductive education can be influential. Misinformation and lack of knowledge about sexual and reproductive health is disturbingly common among young people globally. Parents are concerned that too much education and information could encourage children to earlier sexual activity, despite evidence to the contrary. Withholding information is simply not a matter of morals, but a lack of acceptance of reality with potentially devastating consequences, especially for girls.Citation19

Consequently, there are several approaches that could contribute positively to a more sexually educated young generation: first of all, when looking at the school context, the integration of uterine prolapse in health education and sexual education is considered very important. Lack of monitoring led to inadequate implementation of government strategies on adolescent health education in schools in 2000. Communication between teachers and students in the classroom on reproductive health and sexuality is reported to be very poor. Teachers lack skills and incentives and are reluctant to cover sensitive issues in classes because they fear censure by colleagues and society.Citation20

Another possibility that could be given more focus is the use of young people in participatory approaches. Street drama is a widely used method for disseminating information and awareness of health problems and other social issues to low-income, low-literacy populations, particularly in South Asia. Local, trained school children have already been used in Nepal to communicate several health issues.Citation21 However, we do not know of any attempts in relation to uterine prolapse.

The perspective of service providers

Different professional and organizational backgrounds impact service providers’ opinions on prevention and treatment. It can be seen as positive that health professionals across all levels consider different awareness raising strategies as very important. This is also reflected in women’s level of knowledge of the causes and consequences of uterine prolapse. Unfortunately, the shift to increasing awareness of gender discrimination, reproductive health, and women rights is proven to be more challenging.Citation4

The disagreement among health professionals regarding the use of ring pessaries and pelvic floor muscle training shows the need for action in this field. A ring pessary is a temporary solution for preventing the deterioration of the prolapse. However, such rings are cheap and effective if removed and changed frequently.Citation22 Therefore, the use of ring pessaries in low-income countries with poor service availability and poor personal hygiene is to be questioned. A similar situation is seen with muscle training. Besides preventing and treating uterine prolapse, muscle training has positive effects on urinary and fecal incontinence and lower back pain.Citation23 Furthermore, conversations with health professionals working on pelvic floor exercises showed that doing the exercises together also increases group coherence among women. However, it seems these exercises are quite difficult to integrate into a woman’s daily routines. There is an acute need for research on the effectiveness of pessaries and pelvic floor muscle exercises in developing countries to make decisions regarding national strategies that provide support and guidance with a realistic and implementable monitoring system.

Many health professionals are fond of surgery as treatment for severe prolapse cases. Surgery is the strategy officially promoted by the government of Nepal and is the strategy that is financially supported by national and international donors, but surgery is expensive, time-consuming, and the number of women that can be reached is limited. Surgery for uterine prolapse is necessary to treat severe cases, but in our opinion, the national focus should lie on preventing prolapse. A study following up women who underwent surgery in rural Nepal showed that 50% of women do the same amount of hard physical work after surgery as they did before the operation. This implies a risk for reoccurrence for uterine prolapse, even for operated women.Citation24

There is a range of organizational battles to fight when promoting uterine prolapse prevention. Collaborations between ministries, nongovernmental organizations and international nongovernmental organizations, and private stakeholders (eg, private hospitals) exist, but are limited and far from being used to their maximum capacity. Furthermore, the unstable political situation in the Nepal makes it very difficult to plan long-term prevention interventions and keep up collaborations since government officials (and hence priorities) are changing all too often. It has been proven that regime and government instability have a negative impact on the health of individuals via the link with the quality of health care services.Citation25

Having limited resources affects the quality of services, goods, and human resources, but also requires prioritization of how to allocate available funds. The lack of decisionmaking power and periodical training creates frustration among local health workers on the public level. Having adequate knowledge on how to counsel and treat uterine prolapse along with a minimum amount of resources is very important since patients are vulnerable to and dependent on the decisions made by health professionals.Citation26 Lack of resources such as human resources, equipment, or money remains an obstacle to an efficient health system in many low-income countries.Citation27

Health professionals and service providers also mention the influence of international donors in the prevention of uterine prolapse. That discussion, however, goes beyond the scope of this study.

Conclusion

While preventive and curative services for uterine prolapse are available to some extent in Nepal, the results of this study show that implementation of primary and secondary prevention strategies is a major challenge. Health professionals and service providers know the importance of prevention, but they are confronted with a low-income country with an unstable political situation and lack of resources.

Out of many, we prioritized the following recommendations:

Increased involvement of other target groups (men, adolescents, mothers-in-law, etc)

Conducting research on the effectiveness of ring pessaries and physical exercise for further policy decisions

Stronger integration of uterine prolapse awareness raising and open discussion in reproductive health services to increase the number of women reached

Enforcing transparence, monitoring systems, and collaborations to improve the working environment for public health professionals

Both health professionals and women in Eastern Nepal state that patriarchal structures, gender discrimination, and harmful traditions such as early marriage and pregnancy, son preferences, nutritional habits, and heavy workload (especially before and after pregnancy) are major risk factors for the onset of uterine prolapse.

The study is unique in doing qualitative research on primary and secondary uterine prolapse prevention, combining the perspective of service providers and women in the Nepalese context. It has to be mentioned that it is not the objective of qualitative research to produce generalizable results; rather, the objective is to understand meanings of processes by analyzing experiences subjectively and in a transparent way.

Nepal is a country of contrasts. The study was conducted in only two districts in Eastern Nepal, which is known for its high levels of patriarchy and gender discrimination, as well as a higher uterine prolapse prevalence compared to Northern Nepal. Women in urban areas have better access to health services. In our opinion, the results can be transferred to the rest of Nepal since issues such as stigmatization, lack of open communication about uterine prolapse, and patriarchal values play an important role across the country.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Samita Pradhan, Executive Director of the Centre for Agro-Ecology and Development (CAED) in Kathmandu, for giving us the opportunity to get an entry point for our research in Nepal through the Women’s Reproductive Rights Program. Furthermore, we are thankful to her team in Lahan, which accommodated us and helped us throughout our data collection. We are grateful to all the health professionals and service providers for all the conversations, and we thank all the women in Siraha and Saptari who agreed to talk about this sensitive issue.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WRRPUterine Prolapse Study ReportKathmanduCentre for Agro- Ecology and Development2010

- GurungGRanaAAmatyaABistaKJoshiASayamiJPelvic organ prolapse in rural Nepalese women of reproductive age groups: what makes it so common?Nepal Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology2007223541

- DangalGA study of reproductive morbidity of women in the Eastern Terai Region of NepalNepal Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology2008312934

- PradhanSUnheeded Agonies: A Study of Uterine Prolapse Prevalence and Its Causes in Siraha and Saptari Districts, NepalKathmanduCentre for Agro-Ecology and Development2007

- DeubaARanaPUterus Prolapse: A Key Maternal Morbidity Factor amongst Nepali Women: A StudyKathmanduSafe Motherhood Network Federation2005

- Bodner-AdlerBShrivastavaCBodnerKRisk factors for uterine prolapse in NepalInt Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct2007181343134617333434

- FederationSMNPrevalence of Uterine Prolapse amongst Gynecology OPD Patients in Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital in Nepal and Its Socio-Cultural DeterminantsKuala LumpurThe Asian-Pacific Resource and Research Centre for Women2009

- MesserschmidtLUterine prolapse in Nepal: the Rural Health Development Project’s responseJournal of Nepal Public Health Association2009413342

- FederationSMNProceedings on Formation of Uterine Prolapse AllianceKathmanduSafe Motherhood Network Federation2007

- SharmaSReproductive rights of Nepalese women: current status and future directionsKathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ)200421525419780290

- BonettiTRAEPathakLRListening to “felt needs”: investigating genital prolapse in Western NepalReprod Health Matters2004122316617515242225

- EarthBSthapitSUterine prolapse in rural Nepal: gender and human rights implications. A mandate for developmentCult Health Sex200243281296

- GlaserBStraussAThe Discovery of Grounded TheoryChicagoAldine1967

- CharmazKConstruction Grounded TheoryA Practical Guide Through Qualitative AnalysisLos AngelesSage Publications Ltd2006

- StraussACorbinJBasics of Qualitative ResearchGrounded Theory Procedures and TechniquesLos AngelesSage1990

- ChankapaYPalRTseringDMale behavior towards reproductive responsibilities in SikkimIndian J Community Med2010251404520606918

- QurupSHope for the future: 3. Planning for sonsPeople Planet1995442324

- UNICEFSituation of Children and Women in NepalKathmandu2006

- WoodKMaxwellCAggletonPHIV prevention with especially vulnerable young peopleCase studies of success and innovation [website on the Internet]. Available from: http://www.safepassages.soton.ac.uk/pdfs/evyp_casestudies.pdfAccessed July 26, 2011

- PokharelSKulczyckiAShakyaSSchool-based sex education in Western Nepal: uncomfortable for both teachers and studentsReprod Health Matters2006142815616117101434

- PeltoPSingRCommunity street theatre as a tool for interventions on alcohol use and other behaviors related to HIV AIDSAIDS Behav201014147157

- SassoKHansonLSmithDCase Study: Challenges of pessary managementJ Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs200315215812761487

- BøKCan pelvic floor muscle training prevent and treat pelvic organ prolapse?Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand20068526326816553172

- SchaafJDongolALeeuw-HarmsenLFollow-up of prolapse surgery in rural NepalInt Urogynecol J200819851855

- KlompJHaanJdIs the political system really related to health?Soc Sci Med200969364619427088

- GilsonLTrust and the development of health care as a social institutionSoc Sci Med2003561453146812614697

- GranerSMogrenIDuongLKrantzGKlingberg-AllvinMMaternal health care professionals’ perspectives on the provision and use of antenatal and delivery care: a qualitative descriptive study in rural VietnamBMC Public Health20101060811020043862