Abstract

Objective

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has proven to be effective in weight reduction. This study explores whether individual, 8-session CBT can promote weight loss in midlife women.

Methods

Anthropometric (weight, abdominal perimeter, and body mass index calculation), psychological (health-related and sexual quality of life, stress, anxiety, and depression), and behavioral measures (binge eating disorder and restrained, external, and emotional eating) were assessed at baseline (T1), posttreatment (T2), and 4-month follow-up (T3), for a total of 21 women at baseline; the CBT group (n = 11) and the control group (n = 10; waiting list) were compared.

Results

Statistically significant effects that were dependent on the intervention were observed on weight (F = 4.402; P = 0.035; ηp2 = 0.404; π = 0.652) and body mass index (F = 3.804; P = 0.050; ηp2 = 0.369; π = 0.585); furthermore, marginally significant effects were observed on external eating (F = 2.844; P = 0.095; ηp2 = 0.304; π = 0.461). At follow-up, women in the CBT group presented with lower weight, abdominal perimeter, body mass index, and external eating; higher health-related quality-of-life and restrained eating were also observed in this group. Most differences identified were at a marginally significant level. Moreover, at follow-up, none of the participants of the CBT group met the criteria for binge eating disorder, whereas the number of women with binge eating disorder in the control group remained the same through all three assessments.

Conclusion

An effective, though small, weight loss was achieved. Changes in quality of life were also observed. Moreover, changes in external eating behavior were successful.

Introduction

It has been more than a decade since the World Health Organization (WHO) identified obesity as an epidemic, recognizing it as a public health threat.Citation1 Currently, 30%–80% of adults in the countries of the WHO’s European Region are overweight, and recent studies have shown that, in 2010, almost 150 million adults were obese.Citation2 In the United States, current data points to a prevalence of 33.0% of adults who are overweight and 35.7% who are obese.Citation3

Obesity is a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, type II diabetes, and premature death.Citation4–Citation6 In addition, metabolic and muscular-skeletal benefits as well as brain function improvement may be attained through weight loss and physical fitness.Citation6,Citation7

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has proven to be effective in weight reduction.Citation8–Citation11 However, it is not easy to achieve and maintain this weight loss.Citation8,Citation12

Psychological symptoms can be associated with excessive weight and obesity. Some studies have shown that anxiety, depression,Citation13–Citation15 and stress are strongly related to higher body mass index (BMI) and weight gain, especially in women.Citation16–Citation18 However, this association is not unanimous, given that in another study, anxiety and depression symptoms were not associated with the severity of overweight.Citation19 Furthermore, and independently from the depressive mood, increased stress can predict binge eating.Citation20 The presence of binge eating disorder (BED), as proposed by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-TR,Citation21 increases the likelihood of higher BMI when compared to individuals without BED.Citation22

Research examining BED has shown that CBT can be effective in the reduction or cessation of binge eatingCitation23,Citation24 and its decrease will promote weight reduction.Citation25 A consequence of weight loss can be the improvement of sexual-Citation26 and health-related quality of life (QoL).Citation27,Citation28 However, this conclusion is not unanimous.Citation29

The objective of this study was to explore the efficacy of 8-week individual CBT in reducing weight and binge eating, as well as to investigate whether intervention promotes differences in depression, anxiety, stress, QoL levels, and eating behaviors in a sample of middle-aged women.

Methods

Participants

Twenty-one women agreed to participate in this study. The mean age of the 21 participants was 51 years (M = 51.0; SD = 5.8) and the mean BMI was 29 (M = 29.3; SD = 2.2). describes the participants.

Table 1 Participant characterization

Measures

The sociodemographic characteristics, menopausal status, BMI, and physical exercise were evaluated through self-reported measures.

The menopausal status was defined according to Harlow et al.Citation30 Premenopausal women did not show any changes in their menstrual cycle, perimenopausal women reported cycle variations, and postmenopausal women had a period of at least 12 months of amenorrhea.

Weight and abdominal perimeters were measured by a trained health psychologist, always using the same scale; the remaining variables were assessed through self-reported measures.

Binge eating disorder was explored using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-TRCitation21 criteria, as evidenced in the “Criteria for further study” chapter.

The instruments included the Portuguese adaptation of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales, to assess stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms;Citation31 the Utian Quality of Life Scale, used to explore sexual- and health-related quality of life in menopausal women;Citation32 and the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire,Citation33 to measure restrained, emotional, and external eating behaviors.

Procedure

A study on menopause and body weight was undertaken in the city of Lisbon and the participants’ recruitment was done through community settings (such as schools, universities, and corporate settings) and in the gynecology department of a hospital. The vast majority of respondents who agreed to participate (89% of the sample) were recruited in an educational setting and were mothers and grandmothers of students (only 7% of the respondents were recruited in the hospital and 4% through enterprises). To meet the inclusion criteria, participants had to be female, literate, and between 42 and 60 years old.

The American Psychological Association’s standards on the ethical treatment of participants were followed. A written informed consent form was delivered to all participants, which explained the aims of the study, emphasizing that participation in this research was voluntary and that participants could interrupt their collaboration at any point without consequences. After giving informed consent and agreeing to participate in the research, a community sample of 1003 participants was integrated in the study.

Sociodemographic, health- and menopause-related, lifestyle, psychological, and contextual variables were collected in this cross-sectional study. Women who had participated in the cross-sectional phase were offered voluntarily enrollment in a weight loss intervention if they fulfilled the criteria for overweight or obesity.

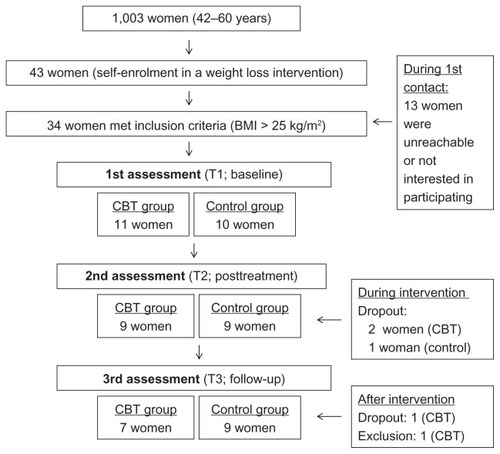

Of the 43 women who enrolled in the intervention program, 34 had a BMI above 24.9 kg/m2 (ie, were overweight or obese). These participants were contacted by telephone, and 13 women were unreachable or unable to participate.

With the support of a computer-generated randomization scheme, 11 participants were selected to undergo individual CBT, and 10 were included in a waiting list (WL). The control group (WL) lasted for the same period as the intervention group, which was 26 weeks. During the intervention, two participants in the CBT and one in the WL dropped out. One participant of the experimental group did not complete the follow-up assessment, and one participant from the same group was not taken into consideration in the statistical analysis because she was diagnosed with an axis II mental disorder. The sample recruitment and retention along the study is presented in .

After the 26 weeks, the nine women on the waiting list began the individual intervention and went from T1 (baseline) until T3 (4-month follow-up); however, their outcomes were not analyzed in the present study in order to maintain the independency of both groups.

Menopausal status, anthropometric measures, and psychological variables were evaluated 1 week before the intervention (or control condition) began, 1 week after it ended, and 4 months after the second assessment. T1, posttreatment (T2), and T3 were conducted by a different psychologist from the one who performed the intervention. Anthropometric measurements were always made using the same weight scale.

To prevent experimenter’s bias, the first psychologist, who was responsible for the assessments, was told that these were done in the context of a study on menopause, without giving any further information on the different groups or specific objectives. The participants were told at the time of the recruitment that any questions regarding the intervention should be addressed to the psychologist who was responsible for the treatment, and a telephone contact was provided for that effect.

The second psychologist, who was responsible for the intervention, had formal training in CBT by the Portuguese Association on Cognitive and Behavioral Therapies.

Intervention

The cognitive-behavioral intervention was structured by two psychologists (and psychotherapists) after a literature review and based on previous interventions. It was planned as presented in . The intervention was individual, conducted in an adequate setting, and performed weekly (each session lasted 60 minutes). Regarding the materials used, in the second session, a matrix entailing seven columns (day/hour; situation; presence of excessive food ingestion; type of food; thoughts before excessive food ingestion; emotions before excessive food ingestion; other comments) was introduced and each participant began filling it in with the psychologist during the second session; the women were asked to continue filling in this report sheet at home over the following 3 weeks. During the fifth session, another matrix was delivered, a table with two columns (achieving my target weight; maintaining my present weight) and two rows (disadvantages; advantages), and used in the context of the motivation increment. This table was completed during the session and analyzed with the psychotherapist.

Table 2 Contents of each session

Statistical analysis

Data was first analyzed to identify outliers and distribution forms. No missing value imputation was made.

To explore if the two groups were homogeneous at baseline, Student’s t-test was used to compare both conditions (experimental and control) on the anthropometric, psychological, and behavioral variables.

Comparisons between groups on the repeated measures were made using mixed repeated measures analysis of variance. A post hoc least significant difference test for mean differences was used to compare the three assessments (T1, T2, and T3) for the anthropometric, psychological, and behavioral measures in each group (CBT and waiting list).

Finally, to explore whether the amount of weight loss in the experimental group was related with educational level and family income, Spearman correlation was used.

Results

The protocol of CBT was implemented as expected, using the structure of sections previously outlined for most participants. Regarding the women who completed the program, the adherence rate to the CBT sessions varied: there was 100% adherence for 5 participants (who attended 8 sessions), 88% for a woman who attended seven sessions, and 75% for one participant (who attended six sessions).

To determine whether the participants who completed CBT differed from those on the waiting list, the two groups were compared regarding anthropometric, psychological, and behavioral variables. presents the results; no significant differences between the two groups in the baseline assessment were observed.

Table 3 Comparison of participants placed in intervention (CBT) with participants in waiting list (WL) at baseline assessment (T1)

To analyze whether weight and psychological changes were dependent on the condition (CBT group versus control group), multivariate tests were conducted. Hence, the variables for which variation was significantly dependent on the condition included weight (F = 4.402; P = 0.035; ηp2 = 0.404; π = 0.652) and BMI (F = 3.804; P = 0.050; ηp2 = 0.369; π = 0.585), while external eating presented a marginally significant dependence on the condition (F = 2.844; P = 0.095; ηp2 = 0.304; π = 0.461). Changes in abdominal perimeter (F = 0.703; P = 0.513; ηp2 = 0.098; π = 0.114), health QoL (F = 0.305; P = 0.742; ηp2 = 0.045; π = 0.089), sexual QoL (F = 0.934; P = 0.418; ηp2 = 0.126; π = 0.177), stress (F = 0.271; P = 0.767; ηp2 = 0.040; π = 0.084), depression (F = 0.232; P = 0.796; ηp2 = 0.034; π = 0.079), anxiety (F = 0.762; P = 0.486; ηp2 = 0.105; π = 0.152), restrained eating (F = 2.560; P = 0.116; ηp2 = 0.283; π = 0.421), and emotional eating (F = 1.534; P = 0.252; ηp2 = 0.191; π = 0.268), were not dependent on the implementation of the CBT.

To explore whether the variables changed during the three assessments under the same conditions, the CBT and the waiting list groups were analyzed separately after the confirmation of sphericity for all variables/groups using the Mauchly test. Results for the control group are presented in . As shown, there were no significant differences in the controlled variables.

Table 4 Waiting list: T1, T2, and T3 assessment for all variables

Changes in the experimental group from the baseline assessment to follow-up are presented in . As demonstrated, significant and marginally significant differences were observed in several variables, including weight, abdominal perimeter, BMI, health QoL, and restrained and external eating (although only changes in weight, BMI, and external eating were proven to be dependent on the experimental condition).

Table 5 CBT: T1, T2 and T3 assessment for all variables

In relation to binge eating disorder (BED), there were differences in the intervention group when comparing T1 (which had 2 women meeting the criteria), both with T2 (1 participant meeting the criteria) and with T3 (none of the participants meeting BED criteria). Regarding the waiting list group, there were no significant differences regarding BED prevalence, since the same number of participants had BED in T1, T2, and T3 (4 women with binge eating disorder and 5 without).

Additionally, within the experimental group, it was observed that the association between both family income (rp = 0.334; P = 0.465) and educational level (rp = 0.335; P = 0.465) with the amount of weight lost was not significant.

Discussion

Being able to reduce weight and maintain the weight loss after the end of an intervention is not easy.Citation8,Citation12 In the present research, the mean weight loss evidenced at follow-up (T3) by the participants who had undergone CBT was 2.4 kg or 3.1% of the baseline weight. In contrast, between baseline and follow-up, the control group had a mean 1.2% increase of their initial weight (that is, a mean increment of 0.8 kg).

Although this reduction was below 5% loss, which has been pointed as a milestone for successful weight loss in other studies,Citation34 it was marginally significant and dependent on the CBT implemented. It is important to note that weight loss was only achieved at the follow-up (comparing T1 with T3, and T2 with T3), with no weight decrease being observed at the post-intervention assessment (comparing T1 with T2). This emphasizes that since this intervention was not focused on caloric decrease or on physical activity promotion (which would likely lead to a rapid weight decrease), this treatment (which entails the identification of excessive food ingestion triggers, and the examination of the successful/unsuccessful implementation of cognitive and behavioral strategies, among others) may take more time to promote an effective change that results in weight loss. However, the loss at the follow-up assessment, 4 months after the last session, indicates that while taking longer (ie, more than the duration of the program itself) to promote a weight decrease, the effects of this intervention can be active and effective long after its implementation.

At the follow-up assessment, a marginally significant increase in restrained eating was observed in the participants who completed the CBT, as well as a significant decrease in external eating. Although changes in eating behavior were expected to follow this intervention, only external eating modifications were directly associated with the CBT implemented since there were no significant interactions between restrained eating and the experimental condition. Thus, this program seems to be effective in reducing the disinhibition or loss of control when facing external stimuli associated with food ingestion.

Additionally, BED also decreased in women who completed the CBT (this reduction was observed immediately after the intervention and at follow-up) when compared with the control group, in which the participants who met the criteria for BED at T1 continued meeting these criteria at follow-up. Although binge eating status and eating behaviors changed between T2 and T3, this did not reflect a successful weight reduction (that is, higher than 5% of the initial weight) after the intervention. This is congruent with the results of prior research which demonstrated that despite the decrease in binge eating behavior, successful weight loss may not be achieved.Citation35 It has been concluded in previous studies examining cognitive-behavioral and behavioral interventions that the former is more effective in reducing binge eating while the latter promotes a greater weight loss reduction by the end of the intervention,Citation11 evidence that supports the results of the present research. Moreover, external eating being the only behavioral change that derives from CBT, and given that both external eating and weight (although the reduction of the latter was only marginally significant and around 3.1% of initial weight) are reduced only at the follow-up assessment, it can be hypothesized that the modification of these two variables is associated.

Cognitive restraint has been associated with a significantly lower energy and fat intake, higher carbohydrate and fiber use, and higher weight reduction at 18-month follow-up.Citation36 This evidence supports the results of the present study: 4 months after the CBT intervention, a marginally significant weight loss was accompanied by an increase in restrained eating and a decline in external ingestion when compared to the baseline assessment, although the increment of restrained eating was not dependent on the CBT since there was no significant interaction between these variables. Other variables, not assessed in this study, may be responsible for this change, such as the increment of perceived control. This data is also in agreement with another study which pointed out that, after 2-year follow-up, participants who managed to maintain their weight also demonstrated the maintenance of the changes in their eating behaviors.Citation37

Cognitive factors and the establishment of clear objectives, components that were approached in this brief CBT, have been evidenced as important when addressing a treatment of this kind, as they can contribute to weight regain.Citation38

It is also important to consider that most women in this study (eight in the CBT group and eight in the control group) were in the menopause phase (perimenopause) or had already gone through menopause (postmenopause). Given that during the menopausal process there are changes in body fat distribution with a loss of lean body mass and an increase in total body fat and visceral fat,Citation39–Citation41 this sample’s characteristics may have had an impact on the success rate observed in this research. Therefore, weight loss programs for menopausal women should consider this and target specific nutritional and physical exercise recommendations, alongside cognitive and behavioural strategies, to avoid or minimize the frequently observed weight gain during the menopausal transition and postmenopause.

The therapy format (group versus individual) has been the subject of debate. There are no significant differences in terms of the intervention’s efficacy when comparing group with individual therapies.Citation42,Citation43 However, in a recent research with a large sample, weight reduction, as well as decrease in blood pressure, glucose, and cholesterol, was higher in a group intervention when compared with an individual approach. This may be due to the encouraging and mutually supportive environment prompted by the group format, which can make the lifestyle changes and long-term maintenance of healthier behaviors easier.Citation44 Consequently, it is suggested that a group format could enhance the efficacy of this CBT. Furthermore, and because contents regarding physical exercise and nutrition were promoted according to general guidelines,Citation45 it would be important in future research to include individualized nutritional and physical exercise plans as a complement to this intervention, given their efficacy in weight reduction.Citation46

Acknowledgments

We kindly acknowledge the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) for the grant SFRH/ BD/32359/2006. We also thank Raquel Oliveira for proof-reading the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health OrganizationObesity: Preventing and Managing the Global EpidemicReport of a WHO ConsultationGenevaWorld Health Organization2000 Available from: http://libdoc.who.int/trs/WHO_TRS_894.pdfAccessed January 10, 2011

- World Health OrganizationThe Challenge of Obesity in the WHO European Region and the Strategies for ResponseBrancaFNikogosianHLobsteinTCopenhagenWorld Health Organization2007

- FryarCDCarrollMDOgdenCLPrevalence of overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity among adults: United States, trends 1960–1962 through 2009–2010Hyattssville, MDNational Center for Health Statistics2012 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_adult_09_10/obesity_adult_09_10.pdfAccessed January 12, 2011

- HuFBMansonJEStampferMJDiet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in womenNew Engl J Med20013451179079711556298

- Van GaalLFMertensILDe BlockCEMechanisms linking obesity with cardiovascular diseaseNature2006444712187588017167476

- XydakisAMCaseCCJonesPHAdiponectin, inflammation, and the expression of the metabolic syndrome in obese individuals: the impact of rapid weight loss through caloric restrictionJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20048962697270315181044

- FrancoOHKarnikKOsborneGOrdovasJMCattMOuderaaFChanging course in ageing research: the healthy ageing phenotypeMaturitas2009631131919282116

- CooperZDollHAHawkerDMTesting a new cognitive behavioural treatment for obesity: a randomized controlled trial with three-year follow-upBehav Res Ther201048870671320691328

- KalodnerCRDeLuciaJLThe individual and combined effects of cognitive therapy and nutrition education as additions to a behavior modification program for weight lossAddict Behav19911652552631776542

- MefferdKNicholsJFPakizBRockCLA cognitive behavioral therapy intervention to promote weight loss improves body composition and blood lipid profiles among overweight breast cancer survivorsBreast Cancer Res Treat2007104214515217058023

- MunshSBiedertEMeyerAA randomized comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and behavioural weight loss treatment for overweight individuals with binge eating disorderInt J Eat Disord200740210211317089420

- DiLilloVSiegfriedNJWestDSIncorporating motivational interviewing into behavioral obesity treatmentCogn Behav Pract2003102120130

- AndersonSECohenPNaumovaENMustAAssociation of depression and anxiety disorders with weight change in a prospective community-based study of children followed up into adulthoodArch Pediatr Adolesc Med2006160328529116520448

- CilliMde RosaRPandolfiCQuantification of sub-clinical anxiety and depression in essentially obese patients and normal-weight healthy subjectsEat Weight Disord20038431932015018383

- LuppinoFSde WitLMBouvyPFOverweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studiesArch Gen Psychiatry201067322022920194822

- BlockJPHeYZaslavskyAMDingLAyanianJZPsychosocial stress and change in weight among US adultsAm J Epidemiol2009170218119219465744

- SerlachiusAHamerMWardleJStress and weight change in university students in the United KingdomPhysiol Behav200792454855317537466

- SmithAWBaumAWingRRStress and weight gain in parents of cancer patientsInt J Obes2005292244250

- CastelliniGLapiFRavaldiCEating disorder psychopathology does not predict the overweight severity in subjects seeking weight loss treatmentCompr Psychiatry200849435936318555056

- FreemanLMGilKMDaily stress, coping, and dietary restraint in binge eatingInt J Eat Disord200436220421215282690

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Text Review4th edWashingtonAmerican Psychiatric Association2000

- GruczaRAPrzybeckTRCloningerCRPrevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in a community sampleCompr Psychiatry200748212413117292702

- EldredgeKLAgrasWSArnowBThe effects of extending cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder among initial treatment nonrespondersInt J Eat Disord19972143473529138046

- WilsonGTFairburnCGEating disordersNathanPEGordonJMGuide to Treatments That Work3rd edNew YorkOxford University Press2007559592

- AgrasWSTelchCFArnowBEldredgeKMarnellMOne-year follow-up of cognitive-behavioral therapy for obese individuals with binge eating disorderJ Consult Clin Psychol19976523433479086701

- KolotkinRLBlinksMCrosbyRDØstbyeTMitchellJEHartleyGImprovements in sexual quality of life after moderate weight lossInt J Impot Res200820548749218596703

- BlissmerBRiebeDDyeGRuggieroLGreeneGMarjorieMHealth-related quality of life following a clinical weight loss intervention among overweight and obese adults: intervention and 24 month follow-up effectsHealth Qual Life Outcomes20064435016846509

- KolotkinRLCrosbyRDWilliamsGRHartleyGGNicolSThe relationship between health-related quality of life and weight lossObes Res20019956457111557837

- MaciejewskiMLPatrickDLWilliamsonDFA structured review of randomized controlled trials of weight loss showed little improvement in health-related quality of lifeJ Clin Epidemiol200558656857815878470

- HarlowSDGassMHallJEExecutive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive agingMenopause201219438739522343510

- Pais-RibeiroJLHonradoALealIContribuição para o estudo da adaptação portuguesa das escalas de ansiedade, depressão e stress (EADS) de 21 itens de Lovibond e LovibondContribution for the study of the adaptation to Portuguese of the Lovibond and Lovibond’s anxiety, depression and stress scales (21-item version)Psicologia Saúde & Doenças20045229239 Portuguese

- PimentaFLealIMarocoJRosaBUtianWAdaptation of the Utian Quality of Life Scale to Portuguese, using a community sample of Portuguese women in pre-, peri- and post-menopauseMenopause2013In press

- van StrienTFrijtersJERBergersGPADefaresPBThe Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional and external eating behaviorInt J Eat Disord198652295315

- TeixeiraPJGoingSBHoutkooperLBPretreatment predictors of attrition and successful weight management in womenInt J Obes200428911241133

- GriloCMMashebRMA randomized controlled comparison of guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss for binge eating disorderBehav Res Ther200543111509152516159592

- KeränenAMStrengellKSavolainenMJLaitinenJHEffect of weight loss intervention on the association between eating behaviour measured by TFEQ-18 and dietary intake in adultsAppetite201156115616220955744

- PekkarinenTTakalaIMustajokiMTwo year maintenance of weight loss after a VLCD and behavioural therapy for obesity: correlation to the scores of questionnaires measuring eating behaviourInt J Obes1996204332337

- CooperZFairburnCGA new cognitive behavioural approach to the treatment of obesityBehav Res Ther200139549951111341247

- HeymsfieldSBGallagherDPoehlmanETMenopausal changes in body composition and energy expenditureExp Gerontol1994293–43773897925757

- MoritaYIwamotoIMizumaNPrecedence of the shift of body-fat distribution over the change in body composition after menopauseJ Obstet Gynaecol Res200632551351616984520

- SternfeldBBhatAKWangHSharpTQuesenberryCPMenopause, physical activity, and body composition/fat distribution in midlife womenMed Sci Sports Exerc20053771195120216015138

- AdamsSOGradyKEWolkCHMukaidaCWeight loss: a comparison of group and individual interventionsJ Am Diet Assoc19868644854903958398

- JefferyRWGillumRGerberWMJacobsDElmerPJPrineasRJWeight and sodium reduction for the prevention of hypertension: a comparison of group treatment and individual counselingAm J Public Health19837366916936846677

- JovanovićŽCrnčević-Orli掊timacDEffects of obesity reduction on cardiovascular risk factors: comparison of individual and group treatment – substudy of the Croatian Healthy Weight Loss ProgrammeColl Antropol200933375175719860100

- World Health OrganizationGlobal Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and HealthGenevaWorld Health Organization2006

- WuTGaoXChenMvan DamRMLong-term effectiveness of diet-plus-exercise interventions vs diet-only interventions for weight loss: a meta-analysisObes Rev200910331332319175510