Abstract

Fallopian tube carcinoma (FTC) is considered a rare malignancy, but recent evidence shows that its incidence may have been underestimated. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) in breast cancer susceptibility gene (BRCA)-positive women has provided a unique opportunity to study the pathogenesis of FTC and ovarian carcinomas. Newer data now suggest that most high-grade serous cancers of the ovary originate in the fimbrial end of the fallopian tube. Due to the presumed rarity of FTC, most current and more recent ovarian cancer clinical trials have now included patients with FTC. The treatment guidelines recommend similar overall management and that the same chemotherapy regimens be used for epithelial ovarian cancers and FTC.

Introduction

Fewer than 500 patients are diagnosed with fallopian tube carcinoma (FTC) every year, representing about 0.2% of cancers diagnosed in women in the United States annually.Citation1 The incidence rate of FTC is between 3.72 and 4.1 per one million women in the United States.Citation1,Citation2 The incidence rate is higher in Caucasian women than in women of African American, Hispanic, or Asian descent.Citation1 Recent evidence shows that the incidence of FTC may have been grossly underestimated.Citation3 In this article, we will highlight the recent literature and understanding of the pathogenesis of FTC that explains the underestimation of its incidence, and the current perspectives in the management of FTC.

Pathogenesis

The origin of epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) was thought to be the neoplastic transformation of cells in the cortical inclusion cysts of the ovary.Citation4–Citation6 The incessant ovulation theory postulated that there is a stepwise accumulation of genetic mutations in the ovarian epithelial lining as a result of repeated damage and repair during ovulation, leading to EOC.Citation6–Citation9 However, it has never been demonstrated conclusively that there exists a precursor lesion in the ovary that progresses to high-grade serous cancer (HGSC).Citation10,Citation11 Another hypothesis is that HGSC originates, not from the surface of the ovary but, from the epithelial layer of the neighboring fimbrial end of the fallopian tube.Citation3–Citation5,Citation8,Citation12–Citation27 Newer data now suggest that HGSC of ovary, primary peritoneal carcinoma (PPC), and FTC have similar pathogenesis and molecular biomarkers and that these cancers should more accurately be called pelvic serous carcinomas.Citation14,Citation28 The epidemiological data also support a common etiology of ovarian, fallopian, and primary peritoneal cancers. There are racial, ethnic, and geographic similarities in the incidence of these three cancers, and the higher incidence of all three cancers in non-Hispanic white women further suggests a common origin.Citation2

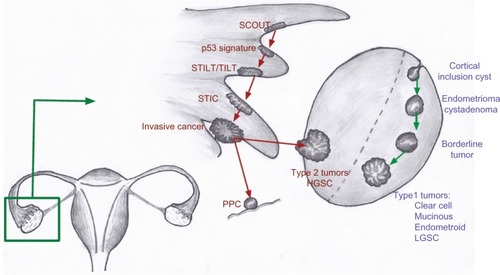

In general, most epithelial cancers in the body arise as a consequence of a series of events and progress from a benign epithelium to an invasive cancer.Citation18 A proposed stepwise sequence to the development of invasive cancers in the fallopian tube is shown in .Citation4,Citation8,Citation16,Citation19,Citation29

Figure 1 A proposed stepwise progression to invasive cancer in the fallopian tube.

The earliest abnormality noted in the fallopian tube epithelium is called secretory cell outgrowth (SCOUT). SCOUTs are discretely localized alterations commonly containing an altered expression of multiple genes within a histologically benign tubal epithelium. Immunohistochemistry shows low expression of paired box 2 (PAX2), low Ki67 index, and, in most cases, no tumor protein p53 (TP53) gene mutations.Citation19 Next, somatic tumor protein 53 (p53) mutations arising from deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) damage appear in the benign tubal epithelium, with foci of strong p53 immunostaining, termed “p53 signatures”.Citation30 The “p53 signature” is defined as 12 or more consecutive cells with strongly positive p53 nuclear staining within a benign-appearing epithelium.Citation15,Citation16,Citation18 In the presence of a p53 signature, proliferative lesions appear, which are called serous tubal intraepithelial lesions (STILs)Citation31 or transitional intraepithelial lesions of the tube (TILTs).Citation22 These lesions are dysplastic and give rise to serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC), also called tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (TIC), which is a precursor for invasive cancer.Citation4,Citation8,Citation31 STIC is composed of secreting cells in the distal fallopian tube, with cytologic atypia, a high proliferative index, and strong nuclear staining for p53.Citation17 The pathogenesis of HGSC from ovarian surface epithelium is unclear as a similar step-wise carcinogenic sequence has never been identified. Recent observations show that STIC may be a precursor lesion for most fallopian tube, ovarian, and peritoneal HGSCs.Citation5,Citation8,Citation14,Citation25

The conventional pathologic classification of pelvic serous cancers mostly as ovarian cancer has contributed to the underreporting of FTCs. FTC is diagnosed only when there is no mass in the ovary or endometrium.Citation14 The presence of a dominant tubal mass and a precursor lesion in the fallopian tube is a prerequisite for classification of a tumor’s origin in the fallopian tube, while the presence of a precursor lesion is not a requirement to diagnose a tumor of ovarian origin.Citation5 Similarly, PPC is diagnosed only when no mass is found on the ovary, fallopian tube, or endometrium. The convention has been to classify serous tumors in the pelvis as ovarian cancer when the origin is unclear.Citation3 This has led to significant underreporting of fallopian tube cancers as many cases of FTC also had tumors on the surface of the ovary and therefore, were classified as serous ovarian cancers.Citation3,Citation23

Molecular pathways

Advances in molecular diagnostics have led to the discovery of different mechanisms driving the EOC histological subtypes.Citation17,Citation32 Type 1 tumors include clear cell, mucinous, and low-grade serous and endometrioid tumors.Citation8,Citation17 These tumors show mutations in the mismatch repair genes, Kirsten rat sarcoma vial oncogene homolog (KRAS), v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (BRAF), catenin (cadherin-associated protein), beta 1, 88kDa (CTNNB), phosphatidylinositol-4,5-biphosphate 3-kinase, catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA), adenine-thymine (AT)-rich interactive domain-containing protein 1A (ARIDIA), protein phosphatase 2, regulatory subunit A, alpha (PPP2R1A), and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN).Citation12,Citation17,Citation20 These tumors have a slow stepwise progression from cortical inclusion cysts to invasive cancer.Citation4,Citation8,Citation12,Citation18 In contrast, type 2 ovarian tumors harbor mutations (as shown in ) in the TP53 gene and are usually HGSC or (some) high-grade endometrioid tumors.Citation12,Citation17 These tumors are aggressive, usually present in advanced stages, and have a worse prognosis.

Figure 2 Proposed models for the development of type 1 and type 2 tumors of the ovary.

Abbreviations: HGSC, high-grade serous cancer; LGSC, low-grade serous cancer; p53, tumor protein 53; PPC, primary peritoneal cancer; SCOUT, secretory cell outgrowths; STIC, serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma; STILT, serous tubal intraepithelial lesions of the tube; TILT, transitional intraepithelial lesions of the tube.

Tumor suppressor p53 inactivation is detected in more than 95% of cases of HGSC.Citation12 Studies reporting the p53 staining of the normal ovarian epithelium in patients with ovarian cancer or those at high risk of ovarian cancer (breast cancer susceptibility gene [BRCA]-positive) have been mixed, with some authors reporting the presence of p53 staining while others finding no evidence of p53 staining on the surface epithelium of the ovary.Citation11,Citation15,Citation33 In BRCA-positive patients who underwent risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomies (RRSO), a p53 signature was found in 38% of examined fallopian tubes, while none of the cortical inclusion cysts had a p53 signature, suggesting a fallopian origin to these cancers.Citation15

Gene expression profiling of HGSC has shown a close correlation to normal fallopian tube epithelium, rather than ovarian epithelium.Citation26,Citation34 Molecular studies have also shown that the different histologies of ovarian cancer have distinct gene expression profiles. While HGSC most closely correlates with normal fallopian tube epithelium, mucinous carcinomas correlate with colonic epithelium; endometrioid and clear cell carcinomas correlate with the endometrium and carry different and specific marker genes.Citation34 Amylase, alpha 2B (AMY2B) and chitinase-3-like protein 1 (CHI3L1) have been shown to be upregulated in serous ovarian cancer and normal fallopian tube epithelium. Endometrioid genes, like fibroblast growth factor homologous factor 9 (FHF9), stratifin (SFN), metallothionein 1G (MT1G), and Indian hedgehog (IHH), have been shown to be expressed in normal endometrium. Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5 (CEACAM5), lectin, galactoside-binding, soluble, 4 (LGALS4), and trefoil factor 2 (TFF2) were all shown to be distinctly expressed in mucinous carcinomas and to be upregulated in normal colon.Citation34 ARID1A mutations are frequent in clear cell and endometrioid ovarian cancer but not in HGSC.Citation35,Citation36 The same mutation is found in the majority of uterine endometrioid carcinomas.Citation37

Evidence of tubal origin of ovarian cancer

RRSO in BRCA-positive and other high-risk women has provided a unique opportunity to study the pathogenesis of ovarian carcinomas, PPC, and FTC.Citation17,Citation18,Citation27,Citation38 There has never been a clear precursor lesion of EOC found on the surface of the ovary in patients undergoing RRSO, in spite of data from thousands of patients at high risk of ovarian cancers (BRCA-positive) who have undergone this procedure. The Sectioning and Extensively Examining the Fimbriated End (SEE-FIM) protocol, used for a more detailed examination of the fallopian tubes in RRSO specimens, has led to an improved understanding of the pathogenesis of pelvis serous cancers.Citation39,Citation40

Retrospective studies

In patients with BRCA mutation who underwent RRSO, thorough examination of the fallopian tube revealed a tubal source 57%–100% of the time when a tumor was identified.Citation8,Citation13,Citation18,Citation38,Citation40,Citation41 In unselected women undergoing RRSO, a tubal origin was found 36%–47% of the time.Citation14,Citation28 Similarly, in a retrospective analysis of 51 patients from a single institution, 56% of patients who were originally classified as having a PPC were found to have STIC in the fallopian tubes.Citation42 In another retrospective review, six out of 76 patients with BRCA1 mutation undergoing RRSO were found to have microscopic cancers. Four of these six patients had a tumor in the fallopian tube, one in the ovary, and the other was in the peritoneal washings.Citation43 In the same study, 78% of patients with BRCA mutations who had stage I to II cancers were found to have a dominant ovarian mass. These data suggest that although HGSC initiation may occur in the fallopian tube, tumor growth and progression may be favored in the ovary, which could be due to a more favorable microenvironment in the ovary.Citation43

In a prospective study of 360 high-risk patients who underwent RRSO, the pathology review included SEE-FIM of the fallopian tube to identify the primary site of disease. In this study, there were two tubal, two ovarian, and four noninvasive STICs, supporting the fallopian tube as a likely site of origin of many pelvic HGSCs.Citation27 In patients who had HGSCs involving the ovary without evidence of a concurrent fallopian tube lesion, it is possible that the fallopian tube was not the only site of tumor initiation.

Treatment of FTC

Due to the presumed rarity of FTC and PPC, there are no large, prospective, randomized clinical trials exclusively evaluating treatment for FTC or PPC. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend similar management, and the same regimens be used for EOC, FTC, and PPC.Citation44 In fact, compared with the older clinical trials in ovarian cancer, most current and more recent ovarian cancer clinical trials have included patients with FTC and PPC, although they are considered distinct clinical entities.Citation45–Citation55 Since the current evidence points toward a common pathogenesis for ovarian cancer, FTC, and PPC, similar treatment of these cancers is likely to be the most appropriate management of all these tumors.

First-line treatment

The first-line treatment of ovarian cancer, FTC, and PPC is a combination of a platinum agent and a taxane.Citation7,Citation56 The combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel was compared with the combination of cisplatin and paclitaxel in the Gynecologic Oncology Group (COG) 158 trial. There was no statistical difference in progression-free survival (PFS) or overall survival (OS) between carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with cisplatin and paclitaxel; however, the carboplatin arm was better tolerated, with fewer nonhematologic side effects.Citation56

The combination of dose-dense weekly paclitaxel and carboplatin every 3 weeks was compared with the standard regimen of both paclitaxel and carboplatin every 3 weeks, in a study done by the Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group. The median PFS was longer in the dose-dense arm (28.0 months versus [vs] 17.2 months) (hazard ratio [HR] 0.71) (P=0.0015). The OS at 3 years was also higher in the dose-dense regimen group (72.1%) than in the conventional treatment group (65.1%) (HR 0.75) (P=0.03) However, there were more hematologic toxicities and treatment discontinuations with the dose-dense paclitaxel, although other toxicities were similar in both arms.Citation57 The recently reported update to this trial, with over 6 years of follow-up, showed a median overall survival greater than 100 months in the dose-dense arm.Citation58

In a Phase III trial (GOG 172) evaluating intraperitoneal therapy, patients with optimally debulked, newly diagnosed ovarian cancer or PPC received intravenous paclitaxel over 24 hours and were randomized to receive either intravenous cisplatin or intraperitoneal cisplatin and intraperitoneal paclitaxel. Although the median PFS (23.8 vs 18.3 months) and OS (65.6 vs 49.7 months) were longer in the intraperitoneal arm when compared with the intravenous arm, there were significantly more grade 3 and 4 toxicities, including pain, fatigue, and gastrointestinal (GI), hematologic, and neurologic toxicities, with only 42% of patients receiving all six cycles of the assigned intraperitoneal therapy.Citation46 Therefore, intraperitoneal therapy should only be considered in patients with very good performance status who are willing to accept the increased toxicity of the regimen. The recently completed GOG 252 trial is evaluating a modified GOG 172 intraperitoneal regimen (which can be given in an outpatient setting) including intraperitoneal carboplatin compared with intravenous carboplatin and paclitaxel, and the results are pending (arm 1: IV paclitaxel, IV carboplatin and IV bevacizumab, arm 2: IV paclitaxel, IP carboplatin and IV bevacizumab, arm 3: IV placlitaxel, IP cisplatin, IP paclitaxel and IV bevacizumab).

The combination of docetaxel plus carboplatinCitation59 is another reasonable first-line option. Due to ease of administration, favorable side-effect profile, long track record, and convenience to patients, the combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel has emerged as the worldwide standard of care in the first-line treatment of advanced ovarian cancer, FTC, and PPC.Citation7,Citation45

The GOG 218 and International Collaboration on Ovarian Neoplasms (ICON) 7 trials evaluated the addition of bevacizumab to front-line chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel. There was improvement in PFS in both trials but no OS benefit.Citation48,Citation49 There were more GI perforations in the patients receiving bevacizumab; however, this was not statistically different. The improved PFS was only observed among patients receiving bevacizumab with chemotherapy and as extended-maintenance treatment and in high-risk patients (36.6 months vs 28.8 months).Citation49

Second-line treatment

Second-line treatment is determined in part by the time since the prior regimen. The platinum-free interval is an important predictor of the response to second-line treatment.Citation60 Patients whose cancer was controlled for greater than 6 months from the last therapy are considered to be platinum sensitive.Citation61 These patients are retreated with a platinum doublet, depending on their comorbidities, prior toxicities, and performance status. Carboplatin, in combination with paclitaxel (ICON4/Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie-Ovarian [AGO-OVAR]-2.2), gemcitabine (Intergroup trial), or PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD) (Caelyx in Platinum Sensitive Ovarian [CALYPSO]) have all been shown to be reasonable options.Citation62–Citation65 In the CALYPSO trial, the combination of carboplatin and PLD was compared with the combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel. Although the OS was not different in the two arms, patients in the PLD arm had a statistically significant improvement in PFS, the primary endpoint of the trial.Citation64,Citation65 The side effect profile also favored the PLD arm.Citation65 Although combinations, in general, have shown an improvement in response rate (RR), PFS, and OS, there is also a higher incidence of side effects. Therefore, in patients with multiple comorbidities or poor performance status, single-agent chemotherapy is appropriate.

Patients who have a recurrence within 6 months of platinum treatment are considered to be platinum resistant.Citation60,Citation61 Patients whose cancers progress while on treatment with platinum are considered to be platinum refractory, and their prognosis is very poor. Platinum agents are not recommended for these patients, and further treatment is based on underlying renal function, hepatic function, and other comorbidities. Patients usually receive sequential therapy with single agents rather than combination therapy. A Phase III trial of weekly paclitaxel was found to be as effective as a combination therapy of paclitaxel with carboplatin or topotecan, in resistant ovarian cancer.Citation66 In a retrospective study, PLD was shown to prolong the platinum-free interval so that patients could be resensitized to a platinum agent.Citation67 However, this study was small, uncontrolled, and retrospective in nature, and in the absence of prospective trials, no firm conclusions can be drawn regarding the prolongation of the platinum-free interval with PLD. Most single-agent regimens produce a RR of 10%–30%. The RRs of commonly used single-agent cytotoxic chemotherapies are reported in . Patients whose disease progresses after two or more consecutive lines of therapy should be considered refractory to platinum and are candidates for early phase clinical trials.Citation68

Table 1 Response rates of single agent chemotherapies in platinum resistant and refractory setting

Targeted agents

Like most other cancers, there has been an increased interest in using targeted therapies in ovarian cancer. The Gynecologic Oncology Group conducted multiple Phase II trials (GOG 170 series) evaluating targeted therapies in patients with refractory ovarian cancer, FTC, or PPC. Most of the targeted therapies tested had minimal activity in these unselected patients. Bevacizumab, aflibercept, and olaparib have been tested in ovarian cancer patients and had some antitumor activity. Other targeted agents examined in this disease, and, their RRs and PFS are shown in .

Table 2 Response rates and progression-free survival of selected targeted agents

Bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody against the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor, in combination with chemotherapy, is useful in both the recurrent platinum-sensitive and in the platinum-resistant setting. The addition of bevacizumab to carboplatin and gemcitabine in platinum-sensitive, recurrent pelvic serous cancers has shown an improvement in RR and PFS but a slightly higher incidence of side effects, including hypertension and arterial thrombosis;Citation50 however, no difference in the OS has been noted, which may be partly due to the subsequent therapy with bevacizumab in the patients who progressed on the placebo arm. In a Phase III trial of patients with platinum resistant disease (AURELIA), patients were randomized to receive investigator-selected chemotherapy (weekly paclitaxel, topotecan, or PLD) with or without bevacizumab.Citation69 The primary end point was Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST)-defined PFS. Patients in the bevacizumab plus chemotherapy arm had a PFS of 5.7 months compared with 4 months in the chemotherapy-only arm (HR 0.48, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.38–0.60) (P<0.001). There were also higher RRs and complete responses in the bevacizumab arm. No OS data are available yet. There were more grade 2 or higher adverse events in the bevacizumab arm, including hypertension, proteinuria, GI perforation, and fistula formation. There were also more grade 3 or higher arterial thromboembolic events.Citation69 Bevacizumab has been tested in Phase II trials as a single agent and been found to have an RR of 21% to 26% and a median PFS of 4.4 months to 4.7 months and is a reasonable option.Citation70,Citation71

Aflibercept, a VEGF trap, was found to be effective in controlling malignant ascites in a double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase II trial in patients who had received a median of four prior therapies.Citation72 The mean time to repeat paracentesis was significantly longer after aflibercept, 55 days vs 23 days. However, there were more grade 3 and 4 side effects, including dyspnea, fatigue, and dehydration. There were also three intestinal perforations with aflibercept.

Olaparib, a poly–adenosine diphosphate (ADP) ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor has shown activity in BRCA-mutant ovarian cancer – patients with BRCA mutations have a defect in the DNA homologous recombination repair mechanism, and PARP inhibitors prevent base excision repair.Citation73–Citation75 Together, these mechanisms achieve tumor cell death by preventing DNA repair via two different pathways, a process referred to as synthetic lethality. A Phase I/II trial in BRCA mutation-positive patients showed an RR of 40%, with a response duration of 28 weeks.Citation76 Other studies have shown RRs from 13% to 33%.Citation77,Citation78 Even in patients with HGSC without BRCA mutation, the RR was 24%.Citation79 Olaparib has been used as maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer and found to prolong the PFS but did not add an OS benefit.Citation80 A Phase I study of olaparib with cediranib, a VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, showed an RR of 44% in recurrent ovarian cancer.Citation81

Future directions

Radical fimbriectomy followed by surveillance has been suggested as an alternative to surveillance alone in high-risk BRCA-positive patients reluctant to undergo bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) for risk reduction of pelvic serous carcinomas, due to concerns of prolonged menopause and other complications (like osteoporosis, vaginal atrophy, and decreased quality of life associated with menopause).Citation21 This approach would preserve the ovaries and consequently delay menopausal symptoms until natural menopause occurs. However, a microscopic spread of the tumor, from the fallopian tube to the ovary, may occur very early; thus, salpingectomy alone may be insufficient to protect against the development of ovarian cancer and may create a false sense of protection.Citation43 Therefore further evaluation of this procedure, with long-term follow-up, is necessary. The early detection of an STIC can help in the prevention of invasive ovarian cancers; however, no screening techniques are currently available to detect STIC. Endometrial cytological testing may detect early-stage ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal HGSCs and may be useful for ovarian cancer screening, but this study needs further validation.Citation82 The inclusion of patients with FTC, PPC, and HGSC of the ovary in clinical trials is recommended as they have similar molecular abnormalities and likely the same cell of origin. The better understanding of FTC biology will lead to improved treatment and, ultimately, improved outcomes in FTC, PPC, and HGSC.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Mahmoud Gaballa, MD, Resident in Internal Medicine at Thomas Jefferson University, for the excellent artwork he provided for this article.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- StewartSLWikeJMFosterSLMichaudFThe incidence of primary fallopian tube cancer in the United StatesGynecol Oncol2007107339239717961642

- GoodmanMTShvetsovYBIncidence of ovarian, peritoneal, and fallopian tube carcinomas in the United States, 1995–2004Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev200918113213919124490

- BerekJSCrumCFriedlanderMCancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneumInt J Gynaecol Obstet2012119Suppl 2S118S12922999503

- CrumCPDrapkinRKindelbergerDMedeirosFMironALeeYLessons from BRCA: the tubal fimbria emerges as an origin for pelvic serous cancerClin Med Res200751354417456833

- CrumCPDrapkinRMironAThe distal fallopian tube: a new model for pelvic serous carcinogenesisCurr Opin Obstet Gynecol20071913917218844

- KatabuchiHOkamuraHCell biology of human ovarian surface epithelial cells and ovarian carcinogenesisMed Electron Microsc2003362748612886939

- HennessyBTColemanRLMarkmanMOvarian cancerLancet200937496981371138219793610

- CheneGDauplatJRadosevic-RobinNCayreAPenault-LlorcaFTu-be or not tu-be: that is the question … about serous ovarian carcinogenesisCrit Rev Oncol Hematol201388113414323523591

- FathallaMFIncessant ovulation – a factor in ovarian neoplasia?Lancet1971277161634104488

- CaseyMJBewtraCHoehneLLTatpatiADLynchHTWatsonPHistology of prophylactically removed ovaries from BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers compared with noncarriers in hereditary breast ovarian cancer syndrome kindredsGynecol Oncol2000783 Pt 127828710985881

- BarakatRRFedericiMGSaigoPERobsonMEOffitKBoydJAbsence of premalignant histologic, molecular, or cell biologic alterations in prophylactic oophorectomy specimens from BRCA1 heterozygotesCancer200089238339010918170

- KesslerMFotopoulouCMeyerTThe molecular fingerprint of high grade serous ovarian cancer reflects its fallopian tube originInt J Mol Sci20131446571659623528888

- CallahanMJCrumCPMedeirosFPrimary fallopian tube malignancies in BRCA-positive women undergoing surgery for ovarian cancer risk reductionJ Clin Oncol200725253985399017761984

- KindelbergerDWLeeYMironAIntraepithelial carcinoma of the fimbria and pelvic serous carcinoma: Evidence for a causal relationshipAm J Surg Pathol200731216116917255760

- FolkinsAKJarboeEASaleemuddinAA candidate precursor to pelvic serous cancer (p53 signature) and its prevalence in ovaries and fallopian tubes from women with BRCA mutationsGynecol Oncol2008109216817318342932

- JarboeEAFolkinsAKDrapkinRInceTAAgostonESCrumCPTubal and ovarian pathways to pelvic epithelial cancer: a pathological perspectiveHistopathology200853212713818298580

- CrumCPIntercepting pelvic cancer in the distal fallopian tube: theories and realitiesMol Oncol20093216517019383378

- FolkinsAKJarboeEARohMHCrumCPPrecursors to pelvic serous carcinoma and their clinical implicationsGynecol Oncol2009113339139619237187

- ChenEYMehraKMehradMSecretory cell outgrowth, PAX2 and serous carcinogenesis in the Fallopian tubeJ Pathol2010222111011620597068

- KurmanRJShihIMMolecular pathogenesis and extraovarian origin of epithelial ovarian cancer – shifting the paradigmHum Pathol201142791893121683865

- LeblancENarducciFFarreIRadical fimbriectomy: a reasonable temporary risk-reducing surgery for selected women with a germ line mutation of BRCA 1 or 2 genes? Rationale and preliminary developmentGynecol Oncol2011121347247621411127

- LeonhardtKEinenkelJSohrSEngelandKHornLCp53 signature and serous tubal in-situ carcinoma in cases of primary tubal and peritoneal carcinomas and serous borderline tumors of the ovaryInt J Gynecol Pathol201130541742421804388

- CrumCPMcKeonFDXianWThe oviduct and ovarian cancer: causality, clinical implications, and “targeted prevention”Clin Obstet Gynecol2012551243522343226

- MingelsMJRoelofsenTvan der LaakJATubal epithelial lesions in salpingo-oophorectomy specimens of BRCA-mutation carriers and controlsGynecol Oncol20121271889322710074

- GaoFFBhargavaRYangHLiZZhaoCClinicopathologic study of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma with invasive carcinoma: is serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma a reliable feature for determining the organ of origin?Hum Pathol20134481534154323465279

- O’ShannessyDJJacksonSMTwineNCGene expression analyses support fallopian tube epithelium as the cell of origin of epithelial ovarian cancerInt J Mol Sci2013147136871370323880844

- ReitsmaWde BockGHOosterwijkJCBartJHollemaHMouritsMJSupport of the ‘fallopian tube hypothesis’ in a prospective series of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy specimensEur J Cancer201349113214122921157

- RohMHKindelbergerDCrumCPSerous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma and the dominant ovarian mass: clues to serous tumor origin?Am J Surg Pathol200933337638319011565

- MehraKMehradMNingGSTICS, SCOUTs and p53 signatures; a new language for pelvic serous carcinogenesisFront Biosci (Elite Ed)2011362563421196340

- LeeYMironADrapkinRA candidate precursor to serous carcinoma that originates in the distal fallopian tubeJ Pathol20072111263517117391

- GrossALKurmanRJVangRShihIeMVisvanathanKPrecursor lesions of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma: morphological and molecular characteristicsJ Oncol2010201012629520445756

- ShenHFridleyBLSongHPRACTICAL ConsortiumAustralian Ovarian Cancer Study GroupAustralian Cancer StudyEpigenetic analysis leads to identification of HNF1B as a subtype-specific susceptibility gene for ovarian cancerNat Commun20134162823535649

- HutsonRRamsdaleJWellsMp53 protein expression in putative precursor lesions of epithelial ovarian cancerHistopathology19952743673718847068

- MarquezRTBaggerlyKAPattersonAPPatterns of gene expression in different histotypes of epithelial ovarian cancer correlate with those in normal fallopian tube, endometrium, and colonClin Cancer Res200511176116612616144910

- WiegandKCShahSPAl-AghaOMARID1A mutations in endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomasN Engl J Med2010363161532154320942669

- LoweryWJSchildkrautJMAkushevichLLoss of ARID1A-associated protein expression is a frequent event in clear cell and endometrioid ovarian cancersInt J Gynecol Cancer201222191422193641

- AyhanAMaoTLSeckinTLoss of ARID1A expression is an early molecular event in tumor progression from ovarian endometriotic cyst to clear cell and endometrioid carcinomaInt J Gynecol Cancer20122281310131522976498

- LeeperKGarciaRSwisherEGoffBGreerBPaleyPPathologic findings in prophylactic oophorectomy specimens in high-risk womenGynecol Oncol2002871525612468342

- LeeYMedeirosFKindelbergerDCallahanMJMutoMGCrumCPAdvances in the recognition of tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: applications to cancer screening and the pathogenesis of ovarian cancerAdv Anat Pathol20061311716462151

- PowellCBKenleyEChenLMRisk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA mutation carriers: role of serial sectioning in the detection of occult malignancyJ Clin Oncol200523112713215625367

- FinchAShawPRosenBMurphyJNarodSAColganTJClinical and pathologic findings of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomies in 159 BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriersGynecol Oncol20061001586416137750

- SeidmanJDZhaoPYemelyanovaA“Primary peritoneal” high-grade serous carcinoma is very likely metastatic from serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: assessing the new paradigm of ovarian and pelvic serous carcinogenesis and its implications for screening for ovarian cancerGynecol Oncol2011120347047321159368

- YatesMSMeyerLADeaversMTMicroscopic and early-stage ovarian cancers in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers: building a model for early BRCA-associated tumorigenesisCancer Prev Res (Phila)20114346347021278312

- MorganRJAlvarezRDArmstrongDKNational Comprehensive Cancer NetworkOvarian cancer, version 3.2012J Natl Compr Canc Netw201210111339134923138163

- OzolsRFBundyBNGreerBEGynecologic Oncology GroupPhase III trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with optimally resected stage III ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group studyJ Clin Oncol200321173194320012860964

- ArmstrongDKBundyBWenzelLGynecologic Oncology GroupIntraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancerN Engl J Med20063541344316394300

- MarkmanMMoonJWilczynskiSSingle agent carboplatin versus carboplatin plus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in recurrent ovarian cancer: final survival results of a SWOG (S0200) phase 3 randomized trialGynecol Oncol2010116332332520044128

- BurgerRABradyMFBookmanMAGynecologic Oncology GroupIncorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancerN Engl J Med2011365262473248322204724

- PerrenTJSwartAMPfistererJICON7 InvestigatorsA phase 3 trial of bevacizumab in ovarian cancerN Engl J Med2011365262484249622204725

- AghajanianCBlankSVGoffBAOCEANS: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancerJ Clin Oncol201230172039204522529265

- AlbertsDSLiuPYHanniganEVIntraperitoneal cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide versus intravenous cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide for stage III ovarian cancerN Engl J Med199633526195019558960474

- GordonANTondaMSunSRackoffWDoxil Study 30–49 InvestigatorsLong-term survival advantage for women treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin compared with topotecan in a phase 3 randomized study of recurrent and refractory epithelial ovarian cancerGynecol Oncol20049511815385103

- PiccartMJBertelsenKJamesKRandomized intergroup trial of cisplatin-paclitaxel versus cisplatin-cyclophosphamide in women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: three-year resultsJ Natl Cancer Inst200092969970810793106

- SchilderRJBradyWELankesHAPhase II evaluation of dasatinib in the treatment of recurrent or persistent epithelial ovarian or primary peritoneal carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group studyGynecol Oncol20121271707422710075

- SeamonLGRichardsonDLCopelandLJEvolution of the Gynecologic Oncology Group protocols in the treatment of epithelial ovarian cancerClin Obstet Gynecol201255113115522343234

- BookmanMAGreerBEOzolsRFOptimal therapy of advanced ovarian cancer: carboplatin and paclitaxel vs cisplatin and paclitaxel (GOG 158) and an update on GOG0 182-ICON5Int J Gynecol Cancer200313673574014675308

- KatsumataNYasudaMTakahashiFJapanese Gynecologic Oncology GroupDose-dense paclitaxel once a week in combination with carboplatin every 3 weeks for advanced ovarian cancer: a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trialLancet200937496981331133819767092

- KatsumataNYasudaMIsonishiSJapanese Gynecologic Oncology GroupLong-term results of dose-dense paclitaxel and carboplatin versus conventional paclitaxel and carboplatin for treatment of advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer (JGOG 3016): a randomised, controlled, open-label trialLancet Oncol201314101020102623948349

- VaseyPAJaysonGCGordonAScottish Gynaecological Cancer Trials GroupPhase III randomized trial of docetaxel-carboplatin versus paclitaxel-carboplatin as first-line chemotherapy for ovarian carcinomaJ Natl Cancer Inst200496221682169115547181

- MarkmanMRothmanRHakesTSecond-line platinum therapy in patients with ovarian cancer previously treated with cisplatinJ Clin Oncol1991933893931999708

- RosePGFuscoNFluellenLRodriguezMSecond-line therapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin for recurrent disease following first-line therapy with paclitaxel and platinum in ovarian or peritoneal carcinomaJ Clin Oncol1998164149414979552057

- ParmarMKLedermannJAColomboNICON and AGO CollaboratorsPaclitaxel plus platinum-based chemotherapy versus conventional platinum-based chemotherapy in women with relapsed ovarian cancer: the ICON4/AGO-OVAR-2.2 trialLancet200336193752099210612826431

- PfistererJPlanteMVergoteIAGO-OVARNCIC CTGEORTC GCGGemcitabine plus carboplatin compared with carboplatin in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer: an intergroup trial of the AGO-OVAR, the NCIC CTG, and the EORTC GCGJ Clin Oncol200624294699470716966687

- WagnerUMarthCLargillierRFinal overall survival results of phase III GCIG CALYPSO trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and carboplatin vs paclitaxel and carboplatin in platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer patientsBr J Cancer2012107458859122836511

- GladieffLFerreroADe RauglaudreGCarboplatin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus carboplatin and paclitaxel in partially platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer patients: results from a subset analysis of the CALYPSO phase III trialAnn Oncol20122351185118921976386

- LortholaryALargillierRWeberBGINECO group FranceWeekly paclitaxel as a single agent or in combination with carboplatin or weekly topotecan in patients with resistant ovarian cancer: the CARTAXHY randomized phase II trial from Groupe d’Investigateurs Nationaux pour l’Etude des Cancers Ovariens (GINECO)Ann Oncol201223234635221562072

- TanguayJSAnsariJBuckleyLFernandoIEpithelial ovarian cancer: role of pegylated liposomal Doxorubicin in prolonging the platinum-free interval and cancer antigen 125 trends during treatmentInt J Gynecol Cancer200919336136619407560

- GriffithsRWZeeYKEvansSOutcomes after multiple lines of chemotherapy for platinum-resistant epithelial cancers of the ovary, peritoneum, and fallopian tubeInt J Gynecol Cancer2011211586521178570

- Pujade-LauraineHilpertFWeberBAURELIA InvestigatorsAURELIA: A randomized phase III trial evaluating bevacizumab (BEV) plus chemotherapy (CT) for platinum (PT)-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer (OC)J Clin Oncol201230Suppl 18 LBA5002. Abstract

- CannistraSAMatulonisUAPensonRTPhase II study of bevacizumab in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer or peritoneal serous cancerJ Clin Oncol200725335180518618024865

- BurgerRASillMWMonkBJGreerBESoroskyJIPhase II trial of bevacizumab in persistent or recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer or primary peritoneal cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group StudyJ Clin Oncol200725335165517118024863

- GotliebWHAmantFAdvaniSIntravenous aflibercept for treatment of recurrent symptomatic malignant ascites in patients with advanced ovarian cancer: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyLancet Oncol201213215416222192729

- UnderhillCToulmondeMBonnefoiHA review of PARP inhibitors: from bench to bedsideAnn Oncol201122226827920643861

- McCabeNTurnerNCLordCJDeficiency in the repair of DNA damage by homologous recombination and sensitivity to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitionCancer Res200666168109811516912188

- BryantHESchultzNThomasHDSpecific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymeraseNature2005434703591391715829966

- FongPCYapTABossDSPoly(ADP)-ribose polymerase inhibition: frequent durable responses in BRCA carrier ovarian cancer correlating with platinum-free intervalJ Clin Oncol201028152512251920406929

- AudehMWCarmichaelJPensonRTOral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancer: a proof-of-concept trialLancet2010376973724525120609468

- KayeSBLubinskiJMatulonisUPhase II, open-label, randomized, multicenter study comparing the efficacy and safety of olaparib, a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancerJ Clin Oncol201230437237922203755

- GelmonKATischkowitzMMackayHOlaparib in patients with recurrent high-grade serous or poorly differentiated ovarian carcinoma or triple-negative breast cancer: a phase 2, multicentre, open-label, non-randomised studyLancet Oncol201112985286121862407

- LedermannJHarterPGourleyCOlaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancerN Engl J Med2012366151382139222452356

- LiuJFTolaneySMBirrerMA Phase 1 trial of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib (AZD2281) in combination with the anti-angiogenic cediranib (AZD2171) in recurrent epithelial ovarian or triple-negative breast cancerEur J Cancer201349142972297823810467

- OtsukaIKamedaSHoshiKEarly detection of ovarian and fallopian tube cancer by examination of cytological samples from the endometrial cavityBr J Cancer2013109360360923868002

- MarkmanMBlessingJRubinSCConnorJHanjaniPWaggonerSGynecologic Oncology GroupPhase II trial of weekly paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) in platinum and paclitaxel-resistant ovarian and primary peritoneal cancers: a Gynecologic Oncology Group studyGynecol Oncol2006101343644016325893

- FerrandinaGLudovisiMLorussoDPhase III trial of gemcitabine compared with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in progressive or recurrent ovarian cancerJ Clin Oncol200826689089618281662

- MutchDGOrlandoMGossTRandomized phase III trial of gemcitabine compared with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancerJ Clin Oncol200725192811281817602086

- MillerDSBlessingJAKrasnerCNPhase II evaluation of pemetrexed in the treatment of recurrent or persistent platinum-resistant ovarian or primary peritoneal carcinoma: a study of the Gynecologic Oncology GroupJ Clin Oncol200927162686269119332726

- ColemanRLBradyWEMcMeekinDSA phase II evaluation of nanoparticle, albumin-bound (nab) paclitaxel in the treatment of recurrent or persistent platinum-resistant ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group studyGynecol Oncol2011122111111521497382

- RosePGBlessingJABallHGA phase II study of docetaxel in paclitaxel-resistant ovarian and peritoneal carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group studyGynecol Oncol200388213013512586591

- RothenbergMLLiuPYWilczynskiSPhase II trial of vinorelbine for relapsed ovarian cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group studyGynecol Oncol200495350651215581954

- MarkmanMHakesTReichmanBIfosfamide and mesna in previously treated advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: activity in platinum-resistant diseaseJ Clin Oncol19921022432481732425

- AlbertsDSJiangCLiuPYWilczynskiSMarkmanMRothenbergMLLong-term follow-up of a phase II trial of oral altretamine for consolidation of clinical complete remission in women with stage III epithelial ovarian cancer in the Southwest Oncology GroupInt J Gynecol Cancer200414222422815086720

- MatulonisUABerlinSIvyPCediranib, an oral inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor kinases, is an active drug in recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancerJ Clin Oncol200927335601560619826113

- FriedlanderMHancockKCRischinDA Phase II, open-label study evaluating pazopanib in patients with recurrent ovarian cancerGynecol Oncol20101191323720584542

- BehbakhtKSillMWDarcyKMPhase II trial of the mTOR inhibitor, temsirolimus and evaluation of circulating tumor cells and tumor biomarkers in persistent and recurrent epithelial ovarian and primary peritoneal malignancies: a Gynecologic Oncology Group studyGynecol Oncol20111231192621752435

- MatulonisUASharmaSGhamandeSPhase II study of MLN8237 (alisertib), an investigational Aurora A kinase inhibitor, in patients with platinum-resistant or -refractory epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal carcinomaGynecol Oncol20121271636922772063

- ColomboNKutarskaEDimopoulosMRandomized, open-label, phase III study comparing patupilone (EPO906) with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in platinum-refractory or -resistant patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian, primary fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancerJ Clin Oncol201230313841384722987083

- CamposSMPensonRTMatulonisUA phase II trial of Sunitinib malate in recurrent and refractory ovarian, fallopian tube and peritoneal carcinomaGynecol Oncol2013128221522022885865