Abstract

Purpose

The validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP-J) have already been confirmed in a population with premenstrual symptoms. This study aimed to assess the validity and reliability of the DRSP-J in the general population.

Patients and Methods

We analyzed data from 113 Japanese women with regular menstrual cycles who applied to participate in an ongoing study. Participants were recruited regardless of the severity of premenstrual symptoms, and their menstrual cycles were monitored using the DRSP-J for two cycles. Reliability was examined using Cronbach’s α, a measure of internal consistency, and test-retest reliability. Structural validity was assessed using a principal component analysis (PCA). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and EuroQol-5 Dimensions-5 Levels (EQ-5D-5L) were used to examine concurrent validity. The agreement between the clinical diagnoses based on the diagnostic criteria for premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder and that based on the DRSP-J score was examined using the kappa coefficient.

Results

Cronbach’s α for DRSP-J total score was 0.96. The DRSP-J total score showed high test-retest reliability. The PCA showed a two-factor model describing “Mood” and “Behavior/Physical” symptoms. The DRSP-J total score was highly correlated with the HADS total and EQ-5D-5L scores. The classification of “moderate to severe premenstrual syndrome” and “premenstrual dysphoric disorder” by clinical methods and the criteria based on the DRSP-J were in good agreement (kappa values = 0.78).

Conclusion

The DRSP-J is a reliable and valid measure of premenstrual symptoms in the general Japanese population, including those with few or no symptoms.

Introduction

Premenstrual symptoms are characterized by a wide range of mood, behavioral, and physical symptoms limited to the luteal PhaseCitation1,Citation2 and affect the social, familial, and school lives of most women. Epidemiological studies have revealed that 80% to 90% of menstruating women exhibit premenstrual symptoms.Citation3 Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is a pathological state of premenstrual symptoms, and a severe form of PMS is diagnosed as premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), primarily owing to its severe psychiatric symptoms.Citation4 Both the PMS diagnostic criteria of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the PMDD diagnostic criteria of the American Psychiatric and Neurological Association require evaluation using a prospective symptom diary.Citation5 Both PMS and PMDD are viewed as premenstrual disorders (PMDs), a series of consecutive disorders.Citation6

The Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP) was originally developed by Endicott to aid in the diagnosis of PMDD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) criteria.Citation7 The DRSP is a prospective daily charting tool used worldwide for the strict evaluation of PMDs.Citation8–10 The DRSP score has been used as the primary endpoint in clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of serotonin reuptake inhibitors and drospirenone-containing oral contraceptives, which are globally recognized as the standard treatments for PMDs.Citation11–14 The DRSP was translated into Japanese after linguistic validation according to a general cross-cultural adaptation process for clinical trials, and a Japanese version of the DRSP (DRSP-J) was developed.Citation15–17 The DRSP-J has been systematically evaluated for its reliability and validity among participants in clinical trials of treatment for PMDs.Citation18

The psychometric characteristics of a survey instrument vary depending on the characteristics of the surveyed population. The reliability and validity of the original version of the DRSP were examined for both clinical trial participants and participants with a wide range of symptom severity, including those with few or no premenstrual symptoms.Citation7 The DRSP-J was considered insufficient compared to the original DRSP, as only clinical trial participants had been examined. Therefore, examining the psychological characteristics of the DRSP-J among the general female population is necessary. This study aimed to assess the validity and reliability of the DRSP-J among the general population.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

This study was performed according to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Kindai University Ethics Committee (approval number: R02-081). All participants provided informed consent before participating in the study.

Settings and Participants

The study was conducted between December 2020 and October 2021. Of the 150 participants in another menstruation-related study, 113 Japanese women with regular menstrual cycles who had completed the study were used in the analysis. Generally, for a questionnaire to be considered reliable and valid, the number of respondents should be 5 to 10 times the number of items (or more than 100 in this case);Citation19 since the DRSP-J total score consists of 21 items, this number of respondents was considered sufficient. Participants were recruited through advertisements placed in local free newspapers, posters displayed in Kindai University Hospital, and our institute’s website. Participants were recruited regardless of the severity of premenstrual symptoms, and their menstrual cycles were monitored using the DRSP-J for two cycles.

The eligibility criteria included: Age 20–45 years; regular menstrual cycles (25–38 days); no oral contraceptive pill use for four weeks before beginning the study; avoiding changes in regularly used foods, supplements, and medications as much as possible after beginning study; and providing written informed consent. No participants were withdrawn from the study after entry for violating these exclusion criteria.

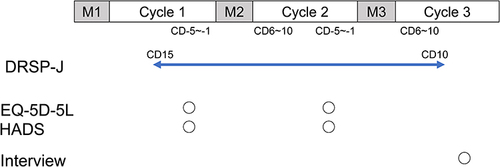

The study participants completed the DRSP-J on the website daily from day 15 of the first menstrual cycle to day 10 of the third menstrual cycle. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and EuroQol-5 Dimensions-5 Levels (EQ-5D-5L) were also recorded simultaneously between day −5 and −1 before menstruation in the first and second cycles. Participants were interviewed by telephone after completion of the DRSP-J and before the start of the next menstrual period. The study schedule is outlined in , and the details of the interviews are presented in the following “Interview” section.

Figure 1 Time course of the study design.

Questionnaire

Japanese Version of the Daily Record of Severity of Problems (DRSP-J)

The DRSP-J consists of 21 items related to emotional and physical premenstrual symptoms (listed in the note of and three items related to impairment of social and life activities due to these symptoms (whether the premenstrual symptoms experienced interfere with (a) work efficiency or productivity, or home responsibilities; (b) social activities; or (c) relationships with coworkers or family). The severity of each symptom is rated on a 6-point scale (1, not at all; 2, extremely mild; 3, mild; 4, moderate; 5, severe; 6, extremely severe). The total DRSP-J score was calculated by summing the 21 premenstrual symptoms (21 to 126 points). The DRSP-J negative mood score was obtained by summing scores on eight core premenstrual mood symptoms (depressed/sad/blue, hopeless, worthless/guilt, anxiety/tense/on edge, mood swings, sensitivity to rejection, anger/irritability, and conflict/problems)(8 to 48 points).Citation20 The luteal phase scores were obtained by averaging the ratings of −5 to −1 day cycles. Follicular phase scores were obtained by averaging the ratings of 6 to 10 day cycles. Participants who answered the questionnaire for at least 4 days during both the follicular and luteal phases were selected.

Table 1 Factor Coefficients of the DRSP-J After Promax Rotation (N=113)

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

A 14-item brief tool was used to assess participants’ risk for anxiety and depression.Citation21 The Japanese version was used, which has been thoroughly reviewed for validity and reliability.Citation22 Since anxiety and depression are central symptoms of premenstrual symptoms, this measure was used to assess concurrent validity. The HADS consists of two parts, each with seven items: HADS-A (anxiety) and HADS-D (depression). Each item is rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3, with anxiety and depression rated according to the total score of HADS-A and HADS-D, respectively. The total of both scores was used for the overall evaluation (HADS-T) (0 to 42 points).

EuroQol-5 Dimensions-5 Levels (EQ-5D-5L)

The EQ-5D-5L measures five dimensions of health-related quality of life (HRQOL): Mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression.Citation23 Each is answered on a 5-point scale, and index values are calculated using an algorithm. The Japanese version was used, which has been thoroughly reviewed for validity and reliability.Citation24,Citation25 The EQ-5D-5L is a reliable and valid general measure of health status, applicable to a wide range of populations and settings, and has been used to assess HRQOL for many conditions, including depression and anxiety.Citation26 Thus, it was used to assess concurrent validity.

Interview

After completing the DRSP-J, participants were interviewed to examine whether the severity of their premenstrual symptoms fulfilled the ACOG criteria for “moderate to severe PMS” or DSM criteria for “PMDD.”Citation4,Citation5 This decision involved a consensus of two expert obstetricians and gynecologists (T.T. and S.K.) with reference to the DRSP-J data for two menstrual cycles. The DRSP-J data showed daily symptom data and menstrual periods. The evaluator visually assessed the relationship between the intensity and increase/decrease of symptoms and the menstrual cycle. In addition to the above, the classification of “moderate to severe PMS” and “PMDD” was made based on the following criteria regarding DRSP-J scores.

Criteria for “moderate to severe PMS” include the following:Citation15

A follicular phase score (days 6–10) daily average ≤ 3.0 for each symptom.

A luteal phase score (days −5 to −1 before menstruation) daily average ≥ 3.0 for three distinct items.

A luteal phase daily average improvement by at least 30% compared with the corresponding follicular phase daily average for three distinct items.

A score ≥ 3 (mild) on functional impairment items for at least 1 day during the premenstrual phase.

“PMDD” criteria include the following:Citation7

A follicular phase score (days 6–10) daily average ≤ 3.0 for each symptom.

A luteal phase (premenstrual days −5 to −1) score of ≥ 4.0 for more than 2 days on five distinct items.

A luteal phase daily average improvement of at least 43% compared with the corresponding follicular phase daily average for five distinct items.

A score of ≥ 4 (moderate) on functional impairment items for at least 2 days during the premenstrual phase.

Both criteria must be met in two consecutive menstrual cycles.

The agreement between classification based on diagnostic criteria and mechanical classification using the DRSP-J score was examined based on kappa values.

Statistical Analysis

Means and standard deviations (SD) were calculated for the age, weight, and height of the participants. The distribution of the DRSP-J total and negative mood scores were shown using the median and interquartile range (IQR).

Cronbach’s α coefficient was used to assess the internal consistency reliabilities of the DRSP-J.

Day-to-day test-retest reliability was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) and a two-way random-effects model. Adjacent days within the follicular and luteal phase (mid-follicular phase day 9 vs day 10 in Cycle 3 and late luteal phase day −2 vs day −1 in Cycle 2) were selected. The reliability was evaluated with a 95% confidence interval (CI), with less than 0.5 rated as poor, 0.5 to 0.75 as moderate, 0.75 to 0.9 as good, and 0.9 or greater as excellent.Citation27

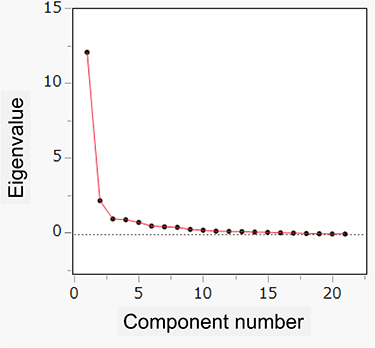

The factor structure of the DRSP-J was examined using principal component analysis (PCA) with promax rotation of the luteal phase scores. The eigenvalue > 1.0 and scree plot criteria were used to determine the number of factors to be extracted.

Correlations were analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients. Correlation coefficients were classified as low (< 0.3), moderate (0.3–0.6), and high (> 0.6).Citation28

Kappa values were categorized as poor (< 0.2), fair (0.21–0.40), moderate (0.41–0.60), good (0.61–0.80), and very good (0.81–1.00).Citation29

For the Student’s t-test, effect size was measured using r. r was calculated using the following formula . The effect sizes were judged as small (0.10), medium (0.30), or large (0.50).Citation30

Except for ICC, statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro 16.0.2 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA). The ICC was calculated using the Excel add-in software BellCurve for Excel 4.0.5 (Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

The basic characteristics of the participants are presented in . Based on the median and IQR of the DRSP-J scores, it can be assumed that most had mild premenstrual symptoms.

Table 2 Characteristics of Study Participants (N=113)

Cronbach’s α for the DRSP-J total score showed very good internal consistency of 0.96 in the luteal phase and 0.95 in the follicular phase (). The Cronbach’s α for the DRSP-J negative mood score also exhibited good internal consistency in the luteal and follicular phases, as in the DRSP-J total score.

Table 3 Internal Consistency (Cronbach’s α) for the Summary Scores of the DRSP-J (N=113)

The test-retest reliability of the DRSP-J is presented in . The test-retest value of the DRSP-J total score in the luteal phase was “moderate” to “excellent” and that of the DRSP-J negative mood score was “moderate” to “good.” In the follicular phase, the DRSP-J total score was “moderate” to “good” and the DRSP-J negative mood score was “moderate.”

Table 4 Test-Retest Intraclass Correlation Coefficients of DRSP-J Total Scores and Negative Mood Score (N=113)*

PCA was performed to explore the factor structure of the DRSP-J. Two factors were identified by the eigenvalue > 1.0 criterion and scree plot (). lists the factor coefficients of DRSP-J after promax rotation. The first factor (Factor 1) explained 51.91% of the data variance and the second factor (Factor 2) 40.27%. Factor 1 can be interpreted as a “mood” dimension and Factor 2 as a “behavior/physical” dimension. The Cronbach’s α for Factors 1 and 2 are provided in . All data were higher than 0.80, indicating good internal consistency.

Figure 2 Scree plot for the DRSP-J.

We then analyzed the consistency of the evaluation of premenstrual symptoms between the DRSP-J, HADS, and EQ-5D-5L (). The DRSP-J total score and negative mood score were highly positively correlated with the HADS total score in both Cycles 1 and 2. For the EQ-5D-5L, the DRSP-J total score and the negative mood score were found to have a high negative correlation.

Table 5 Correlation of Luteal Phase DRSP-J Score with HADS and EQ-5D-5L (N=113)

Additionally, we examined the consistency between conventional clinical diagnosis based on the diagnostic criteria and severity classification based on the DRSP-J score (). The kappa scores indicated good agreement.

Table 6 Consistency Between Conventional Clinical Judgement and Severity Classification by DRSP-J Score (N=113)

To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous EQ-5D-5L scoring studies on participants who kept prospective two-cycle diaries according to the diagnostic criteria for PMS and PMDD. Therefore, we compared the EQ-5D-5L scores in the luteal phase according to the severity of premenstrual symptoms. As only one patient had PMDD in this study, it was considered a PMD group along with a moderate-to-severe PMS group (). EQ-5D-5L scores were significantly lower in the PMD group for both Cycles 1 and 2.

Table 7 Comparison of EQ-5D-5L Scores in the Luteal Phase by Severity of Premenstrual Symptoms

Discussion

In a previous study, we examined the validity and reliability of the DRSP-J for assessing PMDs in clinical trial participants with premenstrual symptoms.Citation16 This study was conducted on general participants with milder symptoms, and the results indicated adequate validity and reliability.

In the luteal and follicular phases, Cronbach’s α of the total DRSP-J score showed high internal consistency, which has been similarly reported in clinical trial settings.Citation16 This value was also similar to the original DRSP value in general participants reported previously.Citation7

The test-retest reliability of the total luteal DRSP-J score in this study matched that reported in clinical trial settings.Citation16 Conversely, the results of the follicular phase data were not as good as those of the luteal phase but were still rated “moderate to good” and are considered reliable enough. This indicates that DRSP-J is sufficiently reproducible for evaluating patients with few premenstrual symptoms.

Regarding PCA, as with the clinical trial participants, we were able to categorize the items into two factors: “Mood” and “Behavior/Physical.” Most of the 21 items comprising the DRSP can be classified into these two categories; however, only 10b (out of control) and 11c (headache) differed from their original classifications. Focusing on the values of these two items, we can assume that both categories are likely related, as both “Mood” and “Behavior/Body” have values above 0.3. Among the DRSP, 1a through 4b, which comprise the negative mood score, are core symptoms that are considered particularly important. The fact that all of these items could be perfectly classified into the “Mood” category is satisfactory for the present study, which targeted the general population, the majority of whom have mild premenstrual symptoms.

The ACOG and DSM diagnostic criteria specify the diagnosis of PMS/PMDD based on a prospective two-cycle symptom diary. There was good consistency between these conventional diagnoses and those defined by the DRSP-J scores. This study was conducted on participants with premenstrual symptoms of various intensities; therefore, the results can be used for actual clinical diagnosis.

The EQ-5D-5L scores for the PMDs group in this study were 0.743 and 0.751 for Cycles 1 and 2, respectively. Considering that the standard value of the EQ-5D-5L for Japanese women aged 30–39 years is 0.944,Citation31 the loss of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) was 0.201 and 0.193 if luteal phase symptoms persisted throughout the menstrual cycle. Considering that these impairments disappeared during the follicular phase, the loss of QALYs due to PMDs would be less than half. An earlier study examining 66 patients with PMDD reported an EQ-5D-3L score 0.795 of the mean value for menstrual cycles.Citation32 Therefore, they concluded that the loss of QALYs from PMDD was approximately 0.14 years. However, it should be noted that in this previous study, PMDD was not diagnosed using a diary of two menstrual cycles of prospective evaluation and was not strictly based on the DSM.

This study has some limitations. The first limitation was the relatively small number of participants (n = 113). These numbers are similar to those reported in previous studies targeting the general population. In the original English version, the number of participants was 27, and 126 in the Chinese version.Citation7,Citation10 Keeping daily records of DRSP is very cumbersome and challenging for participants with few premenstrual symptoms who lack the motivation to describe them. This may be the reason for the difficulty in collecting data from such participants. For exploratory factor analysis, a sample size of at least five times greater than the number of items is required, and the number of people in this study met this requirement. Second, the participants were not sampled from the general population but were participants in a clinical study, which may have overestimated the premenstrual symptoms. However, the purpose of this clinical study was not to study premenstrual symptoms themselves, and there was no advantage for participants to falsely report symptoms and presumably make a correct assessment. As this clinical study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, it had the advantage of covering a wide range of ages in various regions throughout Japan owing to the online enrollment process. Third, there were a small number of cases of moderate to severe PMS and PMDD (ie, PMDs). Owing to the study design involving the general population, the number of PMDs was small (11). Therefore, the results of the QALYs provide limited information. To examine a large number of participants, it is necessary to use clinical trial data of participants treated for PMS/PMDD. Currently, we are collecting EQ-5D-5L data from ongoing clinical trials. The results of this study, which will be reported in the future, will provide more reliable information.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence for the validity and reliability of the DRSP-J as a measure of premenstrual symptoms in the general Japanese female population, including those with symptoms of varying intensity.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of the data; took part in drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit it to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

Prof. Dr. Takashi Takeda reports grants and/or personal fees from Tsumura Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Bayer Pharma Co., Ltd., outside the submitted work. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage for English language editing.

Data Sharing Statement

The data obtained in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Yonkers KA, Simoni MK. Premenstrual disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(1):68–74. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.05.045

- Takeda T. Premenstrual disorders: premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2023;49(2):510–518. doi:10.1111/jog.15484

- Angst J, Sellaro R, Merikangas KR, Endicott J, Endicott J. The epidemiology of perimenstrual psychological symptoms. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104(2):110–116. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00412.x

- American Psychological Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 TR. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

- Hofmeister S, Bodden S. premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(3):236–240.

- O’Brien PMS, Backstrom T, Brown C, et al. Towards a consensus on diagnostic criteria, measurement and trial design of the premenstrual disorders: the ISPMD Montreal consensus. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(1):13–21. doi:10.1007/s00737-010-0201-3

- Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W. Daily record of severity of problems (dRSP): reliability and validity. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9(1):41–49. doi:10.1007/s00737-005-0103-y

- Schmidt K, Weber N, Steiner M, et al. A lecithin phosphatidylserine and phosphatidic acid complex (PAS) reduces symptoms of the premenstrual syndrome (PMS): results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018;24:22–30. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2018.01.067

- Henz A, Ferreira CF, Oderich CL, et al. premenstrual syndrome diagnosis: a comparative study between the daily record of Severity of problems (DRSP) and the premenstrual symptoms screening tool (PSST). Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2018;40(1):20–25. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1608672

- Wu L, He Z, Zhao H, et al. Chinese version of daily record of severity of problems: reliability and validity. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(2):449–456. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06070.x

- Pearlstein TB, Bachmann GA, Zacur HA, Yonkers KA. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with a new drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive formulation. Contraception. 2005;72(6):414–421. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2005.08.021

- Pearlstein TB, Halbreich U, Batzar ED, et al. Psychosocial functioning in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder before and after treatment with sertraline or placebo. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(2):101–109. doi:10.4088/JCP.v61n0205

- Yonkers KA, Halbreich U, Freeman E, et al. Symptomatic improvement of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with sertraline treatment. A randomized controlled trial. sertraline premenstrual dysphoric collaborative study group. JAMA. 1997;278(12):983–988. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03550120043031

- Shehata NA. Calcium versus oral contraceptive pills containing drospirenone for the treatment of mild to moderate premenstrual syndrome: a double blind randomized placebo controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;198:100–104. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.01.015

- Takeda T, Shiina M, Chiba Y. Effectiveness of natural S-equol supplement for premenstrual symptoms: protocol of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e023314. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023314

- Takeda T, Shiina M, Yamada K. Development of the Japanese version of the daily record of severity of problems (DRSP): translation and linguistic validation. Clin Gyneco Obstet. 2019;73(8):807–811.

- Takeda T, Chiba Y. Evaluation of a natural S-equol supplement in treating premenstrual symptoms and the effect of the gut microbiota: an open-label pilot study. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2022;42(2):127–134. doi:10.1002/npr2.12234

- Takeda T, Kai S, Yoshimi K. Psychometric testing of the Japanese version of the daily record of severity of problems among Japanese women. Int J Womens Health. 2021;13(1179–1411 (Print)):361–367. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S301260

- MacCallum RC, Widaman KF, Preacher KJ, Hong S. sample size in factor analysis: the role of model error. Multivar Behav Res. 2001;36(4):611–637. doi:10.1207/S15327906MBR3604_06

- Bixo M, Ekberg K, Poromaa IS, et al. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with the GABA(A) receptor modulating steroid antagonist sepranolone (UC1010)-A randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;80:46–55. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.02.031

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

- Kugaya A, Akechi T, Okuyama T, Okamura H, Uchitomi Y. Screening for psychological distress in Japanese cancer patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1998;28(5):333–338. doi:10.1093/jjco/28.5.333

- Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727–1736. doi:10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x

- Ikeda S, Shiroiwa T, Igarashi A, et al. Developing a Japanese version of the EQ-5D-5L value set. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;64(1):47–55.

- Shiroiwa T, Fukuda T, Ikeda S, et al. Japanese population norms for preference-based measures: EQ-5D-3L, EQ-5D-5L, and SF-6D. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(3):707–719. doi:10.1007/s11136-015-1108-2

- Feng YS, Kohlmann T, Janssen MF, Buchholz I. Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L: a systematic review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(3):647–673. doi:10.1007/s11136-020-02688-y

- Koo TK, Li MY. a guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15(2):155–163. doi:10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

- Andresen EM. Criteria for assessing the tools of disability outcomes research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(12 Suppl 2):S15–20. doi:10.1053/apmr.2000.20619

- Altman DG. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. CRC press; 1990.

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–159. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

- Shiroiwa T, Noto S, Fukuda T. Japanese population norms of eq-5d-5l and health utilities index mark 3: disutility catalog by disease and symptom in community settings. Value Health. 2021;24(8):1193–1202. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2021.03.010

- Yamada K, Kamagata E. Reduction of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) in patients with premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). Qual Life Res. 2017;26(11):3069–3073. doi:10.1007/s11136-017-1642-1