Abstract

Purpose

This study aims to examine the mediating effect of life stress and the moderated mediating effect of job satisfaction on work–family conflict and depression among working mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A secondary analysis was conducted using raw data from Wave 8 of the Korean Longitudinal Survey of Women and Families, collected during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021. Among the 9175 respondents, study included 1315 women aged between 26 and 55, who have children cohabiting with them. Data analysis involved descriptive statistics; T-test, ANOVA, and Pearson’s correlation. The analysis was conducted using the SPSS/WIN 26.0 program and the SPSS PROCESS macro (version 4.0).

Results

Life stress was observed to have a significant mediating effect (indirect effect) on work–family conflict and depression. Within this indirect effect, job satisfaction was found to play a moderated mediating role.

Conclusion

Drawing from these findings, various interventional strategies can be devised to alleviate work–family conflict and life stress, and enhance job satisfaction, thereby improving the mental health of working mothers. Additionally, these results offer valuable insights for developing mental health promotion programs aimed at preventing and preparing for crises such as infectious diseases and can contribute to inform health policy-making.

Introduction

Background

The participation rate of married women in economic activities has been steadily increasing. Over the past decade, the employment rate of women aged 15–64 in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries has steadily risen from 50.7% in 2011 to 62.2% in 2022. In Korea, the employment rate of women in this age group increased from 53.1% to 60.0% during the same period.Citation1 In 2022, the number of married employed women aged 15–54 with children under 18 increased by 16,000 year-on- year.Citation2

In the wake of increasing social participation by women, married employed women, who manage dual roles at work and home, often face chronic stress, making them particularly susceptible to mental stress and depression.Citation3 Work–family conflict refers to the tension that arises from managing responsibilities both at work and family domains.Citation4 This form of role conflict is driven by the distinct demands of their roles at work and home.Citation5 Given that individuals are often overwhelmed and stressed by roles that exceed their capacity, there is a compelling need to minimize work–family conflict.Citation4 Married employed women with children in the household (hereinafter referred to as “working mothers”) are constantly exposed to the triple stressors of parenting, household duties, and job responsibilities, making them prone to chronic stress.Citation6,Citation7 They frequently experience chronic fatigue and depression while playing multiple roles, with work–family conflict being the primary and ongoing factor affecting their mental health.Citation8

COVID-19 significantly increased the burden of childcare at home as schools and daycare centers remained closed, and social relationships diminished, posing exceptionally heightened difficulties to working mothers.Citation9 The pandemic had a significant negative impact on women, a socio-economically vulnerable group.Citation9 Data from the Korea Labor Institute (2020) indicate that women’s household labor time and associated stress have escalated following the pandemic, leading to financial strains.Citation10

Korean working mothers, who are often expected to uphold traditional female roles in a patriarchal culture, frequently encounter work–family conflict as they attempt to balance their professional and family life.Citation11 In addition to handling traditional household and parenting responsibilities, they also face various forms of stress, further compounded by job-related pressure. During the day, they navigate stress from diverse work tasks and interpersonal relationships, and seamlessly transition to managing household chores and providing childcare after work.Citation6 Contrary to major life events like divorce or childbirth, it is the accumulation of minor daily stresses that can profoundly impact mental health.Citation12 Consequently, the day-to-day stress experienced by working mothers becomes increasingly ubiquitous and intense.Citation3 When family demands, such as childcare and household responsibilities, surpass a certain threshold, it detrimentally affects women’s mental health, intensifying stress and potentially leading to depression.Citation7 Therefore, psychological factors, such as depression and continuous stress exposure faced by working mothers, should not be trivialized as mere individual issues, but need to be sensitively regarded as mental health concerns closely tied to the stress and depression inherent in achieving a work–family balance.

Job satisfaction is closely associated with attitudes toward assigned tasks, rewards, costs, and interpersonal relationships as members of an organization.Citation13 It has been reported that occupational variables of married employed women significantly impact both their physical and mental health,Citation14 with higher job satisfaction and lower job stress being positively correlated with better mental health. Research has demonstrated that work–family conflict adversely affects mental health, leading to depression. Workers experiencing greater work–family conflict tend to have higher levels of depression compared to others.Citation15–17 Stress is related by work–family conflict and job satisfaction. Role conflicts for women both in work and family settings act as stressors, leading to job dissatisfaction, tension, and health issues.Citation18 There is a positive correlation between work–family conflict and job stress, which adversely affects married employed women.Citation19 Therefore, from a national perspective, it is essential to understand the job satisfaction of working mothers and explore how it impacts mental health. This understanding is key to ensuring their continuous participation in economic activities from a quantitative perspective and efficient contribution from a qualitative perspective.

The work–family conflict experienced by working mothers affects life stress and depression, with the degree of depression varying according to job satisfaction.Citation3,Citation8,Citation14,Citation15,Citation17,Citation20 Accordingly, it can be inferred that the intensity of life stress in the relationship between work–family conflict and depression may vary depending on the level of job satisfaction. However, previous studies have only verified causal relationships or simple mediation. There is a lack integrated studies the moderated mediating role of job satisfaction in influencing the degree of depression under different conditions and situations for working mothers. Moreover, previous research relied on small sample size surveys. Therefore, using panel databases during the COVID-19 pandemic, we aimed to comprehensively examine the mediation effect of life stress and the moderated mediation effect of job satisfaction in the effect of work–family conflict on depression among working mothers.

To address this research gap, this study aims to verify the mediating effect of life stress on work–family conflict and depression among working mothers during COVID-19. Additionally, it seeks to comprehensively examine the moderated mediating effect of job satisfaction in the pathway by which work–family conflict affects depression through the mediation of life stress. The study provides practical data for developing mental health promotion programs aimed at preventing and preparing for crises such as pandemics, and it can contribute to inform health policy-making.

Conceptual Model and Research Objectives

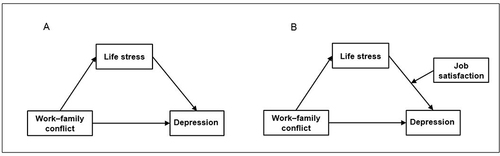

This study aims to construct and test a model that explains the mediating effect of life stress and the moderated mediating effect of job satisfaction on work–family conflict and depression among working mothers. It is a descriptive research study conducted as a secondary analysis using raw data from Wave 8 of the Korean Longitudinal Survey of Women and Families conducted in 2021. Previous studies have demonstrated the impact of work–family conflict on life stress and depression.Citation3,Citation8 Life stress also affects depression,Citation7,Citation21 and its mediating effect was confirmed in the relationship between work–family conflict and depression.Citation7,Citation18 Job satisfaction is a key variable that reduces work–family conflict and depression,Citation14 and the level of depression among working mothers was found to vary depending on their job satisfaction.Citation3,Citation20 Drawing on these previous studies, a conceptual model was formulated as follows ().

| 1) | Examine the subjects’ work–family conflict, life stress, depression, and job satisfaction. | ||||

| 2) | Examine the subjects’ work–family conflict, life stress, depression, and job satisfaction based on their general characteristics. | ||||

| 3) | Examine the mediating effect of life stress in the relationship between the subjects’ work–family conflict and depression. | ||||

| 4) | Examine the moderated mediating effect of job satisfaction that moderates the mediation effect of life stress in the relationship between the subjects’ work–family conflict and depression. | ||||

Figure 1 Mediation effect model of Life Stress and moderated mediation effect model of Job Satisfaction. Conceptual framework of mediation model (A). Conceptual framework of moderated mediation model(B).

Based on the above literature review, this study proposed two hypotheses ().

Hypothesis 1. Life stress mediates the relationship between the work–family conflict and depression.

Hypothesis 2. Job satisfaction moderates the indirect association between the work–family conflict and depression via life stress.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study involves a descriptive survey conducted as a secondary analysis using raw data from Wave 8 of the Korean Longitudinal Survey of Women and Families (2021).

Research Data and Participants

The analysis is based on data from the Korean Longitudinal Survey of Women and Families conducted by the Korean Women’s Development Institute in 2021, which provides valuable information on various aspects of Korean women’s lives, families, economic activities, and values. It also includes diverse data related to family behavior, such as childbirth and child-rearing. The target population of the survey consists of 9997 women living in 9068 households across the country, with women aged 19–64 as household members sampled across South Korea. The survey was conducted at one-year intervals between Wave 1 (2007) and Wave 2 (2008). Starting from Wave 3, the survey was conducted every other year, with the most recent survey completed in 2021.

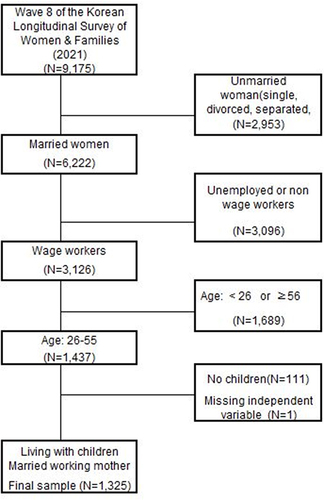

The survey was conducted using computer-assisted personal interviewing, where interviewers contacted selected panel members, asked them questions based on a structured questionnaire using computers, and immediately transmitted the collected data.Citation22 For this study, data from Wave 8 conducted in 2021 were utilized. Initially, 9175 respondents were included, from whom 6222 married women were extracted. Among them, 3126 were wage workers. From this group, 1326 were identified as mothers aged between 26 and 55, with children living in the household. After excluding one case with missing independent variable data, a total of 1325 participants were included as subjects in the study ().

Research Tools

Independent Variable: Work–Family Conflict

Work–family conflict was assessed by measuring conflict in the context of working mothers with adolescent children facing the dual demands and responsibilities of work and family. Respondents were asked to rate how their work experience was affecting their family life, with response options being “very much”, “somewhat”, “not really”, and “not at all”. Detailed items included: (1) Working gives me a sense of fulfillment and energy in life; (2) I believe that working allows me to gain recognition from family members; (3) Working makes family life more satisfying; (4) Working has a positive impact on my children; (5) Working long hours interferes with family life; and (6) Irregular working hours interfere with family life. Reverse-coded items 5 and 6 were analyzed after recoding. A higher total score of the six items indicates a greater level of work–family conflict experienced in the workplace. The reliability of the work–family conflict scale used in this study was measured as 0.730.

Mediating Variable: Life Stress

Life stress was assessed using an 8-item scale designed to measure the level of stress the respondents experienced in their daily lives in light of their thoughts and emotions. Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = very much, 2 = somewhat, 3 = not really, 4 = not at all). The items included: (1) I experience stress at work, home, or school; (2) I sometimes drink alone when I feel depressed; (3) I believe watching TV or using the internet alone is more enjoyable than meeting people; (4) I often get angry at others without a specific reason; (5) I have no one to talk to over serious concerns; (6) I can easily relieve stress during stressful situations; (7) I experience stress due to economic reasons; and (8) I experience stress due to interpersonal relationships. Seven items, except for item 6, were used after recoding. A higher total score indicates a higher level of daily life stress. The reliability of this scale was measured as 0.710.

Dependent Variable: Depression

Depression was assessed using the 10-item CES-D-10 (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). The scale assesses the extent to which respondents experienced certain emotions and behaviors during the past week. They include: (1) I was bothered by things that usually do not bother me; (2) I had trouble focusing on what I was doing; (3) I felt depressed; (4) I felt like everything was laborious; (5) I felt hopeful about the future; (6) I felt fearful; (7) My sleep was disturbed; (8) I was happy; (9) I felt lonely; and (10) I could not keep myself going. Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale: 0 = rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day), 1 = some or little of the time (1–2 days), 2 = occasionally or a moderate amount of time (3–5 days), and 3 = most or all of the time (5–7 days). Items 5 and 8 are reverse-scored. A higher total score indicates a greater level of depression. The reliability of the CES-D-10 in this study was measured as 0.750.

Moderating Variable: Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction was assessed on the 10-item job satisfaction scale used in the Korean Longitudinal Survey of Women and Families, which measured the extent to which respondents were satisfied with their current job. The items focused on (1) income, (2) job stability, (3) job content, (4) work environment, (5) growth potential, (6) development potential, (7) interpersonal relationships at work, (8) fringe benefits, (9) recognition of performance, and (10) overall job satisfaction. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very satisfied, 2 = somewhat satisfied, 3 = neutral, 4 = somewhat dissatisfied, 5 = very dissatisfied). The total scale score, obtained after recoding all items, represented the level of job satisfaction, with a higher total score indicating greater job satisfaction. The reliability of the job satisfaction scale in this study was measured as 0.910.

Ethical Considerations

This study was granted an exemption from review by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of U1 University (Project No.: U1IRB2023-15), as it utilized publicly available secondary data from the website of the Korean Women’s Development Institute. The study qualified for an exemption under Article 13(1)3 of the Enforcement Decree of the Bioethics and Safety Act.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using the SPSS/WIN 26.0 program and SPSS PROCESS macro (version 4.0).Citation23 The reliability of the psychometric tools was determined using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the general characteristics of the subjects and the scores of the variables. Differences in depression based on the subjects’ characteristics were analyzed using independent t-tests and one-way ANOVA. For post hoc analysis, Scheffe’s test was utilized.

The relationship between work–family conflict, life stress, depression, and job satisfaction were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation. The mediating effect of life stress on the impact of work–family conflict on depression was analyzed using PROCESS Macro Model 4, followed by testing the statistical significance of the mediating effect (indirect effect), ie the causal relationship between the independent variable (X) on the dependent variable (Y) via mediating variable (M).Citation23

Using PROCESS Macro Model 14, we analyzed the moderated mediating effect of job satisfaction on the impact of work–family conflict and depression through life stress, and examined the statistical significance of the conditional indirect effect and the moderated mediation index.Citation23,Citation24 The moderated mediating effect signifies that the strength of the mediating effect is moderated by the moderator variable (W) in the causal pathway from the independent variable (X) to the dependent variable (Y) via the mediating variable (M). Essentially, the presence of a moderated mediating effect is established when the moderated mediation index is statistically significant.Citation23,Citation24 To assess the significance of the indirect effect, conditional indirect effect, and moderated mediation index, bootstrapping was employed with 5000 resampled samples, based on the lower and upper limits of the estimated by analyzing the 95% bootstrapping confidence interval.Citation23,Citation24 The significance of the moderated mediating effect of job satisfaction was determined using the Johnson-Neyman technique within the PROCESS macro (p<0.05).Citation23,Citation24

Results

Differences in Depression According to Subjects’ General Characteristics

Among the respondents, 4.0% were aged below 35, while 54.7% were between 35 and 45. Regarding educational level, 1.9% had completed middle school or lower, 41.5% were high school graduates, 23.5% had associate degrees, 29.1% had bachelor’s degrees, and 4.1% had master’s degrees or higher. In terms of subjective health status, 69.4% reported to be in good health, 27.4% average, and 3.1% poor. Household income over the past year was categorized into the upper (25%), median (50%), and lower quartiles (25%). The majority of respondents had two children living at home (62.3%), followed by those with one child (21.6%), and three or more children (16.1%). In the variable of living together preschool children, 85.8% had no preschool children and 14.2% had preschool children.

Regarding satisfaction with the husband’s contribution to household chores, 3.6% were very satisfied, 40.7% generally satisfied, 34.0% were average, 14.9% were not very satisfied, and 6.8% were not at all satisfied. Only 9.6% had domestic help, with the majority (90.4%) managing the household without external assistance. In terms of employment status, 58.0% held regular positions while 42% were in irregular positions. Relative to the period before COVID-19, household income mostly remained the same (73.7%), with 22.8% reporting a decrease, and 3.5% an increase.

Among the general characteristics of the respondents, statistically significant differences in the level of depression were found in subjective health status (p<0.001), annual household income (p=0.001), and satisfaction with the husband’s contribution to household chores (p<0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed that a lower subjective health status was associated with a higher level of depression, while a higher annual household income was associated with a lower level of depression. Furthermore, the level of depression was higher among those who were not at all satisfied with the husband’s contribution to household chores ().

Table 1 Differences in Depression According to Subjects’ General Characteristics

Correlation Between Work–Family Conflict, Life Stress, Depression, and Job Satisfaction

In a correlation analysis between work–family conflict, life stress, depression, and job satisfaction, there was a significant positive correlation with life stress (r = 0.27, p < 0.001) and depression (r = 0.19, p < 0.001) and a significant negative correlation with job satisfaction (r = −0.32, p < 0.001). Life stress was found to have a significant positive correlation with depression (r = 0.38, p < 0.001) and a significant negative correlation with job satisfaction (r = −0.23, p < 0.001). Depression exhibited a significant negative correlation with job satisfaction (r = −0.14, p < 0.001). ().

Table 2 Correlation Between Work–Family Conflict, Life Stress, Depression, and Job Satisfaction

The Mediating Effect of Life Stress on the Impact of Work–Family Conflict on Depression Among Married Employed Women

After controlling for subjective health status, annual household income, and satisfaction with the husband’s contribution to household chores, which significantly influenced depression levels, the mediating effect of life stress on the relationship between work–family conflict and depression was examined using PROCESS macro 4. Bootstrapping was utilized to determine the statistical significance of the indirect effect. In Step 1, work–family conflict (independent variable, X) had a significant impact on depression (dependent variable, Y) (B = 0.16, p < 0.001). In Step 2, the impact of work–family conflict (X) on life stress (mediator, M) was also significant (B = 0.21, p < 0.001). In Step 3, within the model including work–family conflict (X), the direct effect of life stress (M) on depression (Y) was significant (B = 0.36, p < 0.001), as well as the mediating effect (indirect effect) of work–family conflict (X) on depression (Y) through life stress (M) (B = 0.09, p < 0.001). The mediating effect of life stress in the causal relationship between work–family conflict and depression was determined to be 0.07, a significant value within the 95% confidence interval, not including 0 ().

Table 3 the Mediating Effect of Life Stress on the Impact of Work–Family Conflict on Depression Among Married Employed Women

The Moderated Mediating Effect of Job Satisfaction on Work–Family Conflict and Depression Through Life Stress Among Married Employed Women

After controlling for subjective health status, annual household income, and satisfaction with the husband’s contribution to household chores, which significantly influenced depression levels, the mediating effect of life stress on the relationship between work–family conflict and depression was examined using the PROCESS macro 4. Bootstrapping was employed to assess the statistical significance of the indirect effect.

Step 1 demonstrated that the impact of work–family conflict (X) on life stress (M) was significant (B = 0.20, p< 0.001). In Step 2, both the direct effect of work–family conflict (X) on depression (Y) (B = 0.07, p=0.02) and the effect of life stress (M) on depression (Y) (B = 0.79, p< 0.001) were significant. The effect of job satisfaction (W) on depression (Y) was also found significant (B = 0.28, p< 0.001). Likewise, the interaction term of life stress (M) and job satisfaction (moderator variable, W) (M × W) on depression (Y) was significant (B = −0.13, p = 0.04) ().

Table 4 The Moderated Mediating Effect of Job Satisfaction on Work–Family Conflict and Depression Through Life Stress Among Married Employed Women

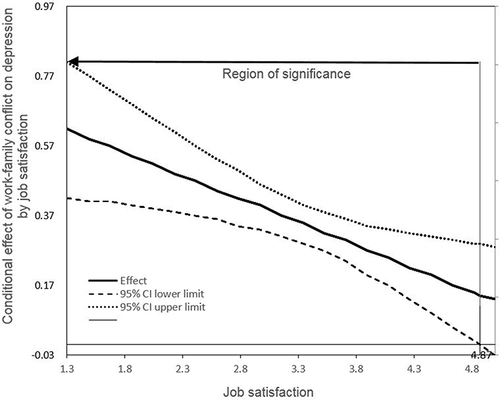

The conditional indirect effect of job satisfaction was statistically significant across all three groups: below-average (mean-1SD; effect = 0.41, 95% CI = 0.34–0.48), average (mean; effect = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.28–0.39), and above-average (mean+1SD; effect = 0.26, 95% CI = 0.19–0.34). The impact of work–family conflict on depression through the mediation of life stress was found to be more pronounced in groups with lower job satisfaction, with satisfaction scores inversely correlated with the strength of its moderated mediating effect. Specifically, the lower the job satisfaction scores, the greater the strength of the mediating (indirect) effect of work–family conflict on depression through life stress. According to the Johnson-Neyman analysis, the moderated mediating effect of job satisfaction was significant when job satisfaction scores were below 4.87 (within a possible range of 1–5) (). This suggests that job satisfaction scores had an inverse relationship with the mediating effect of life stress on the relationship between work–family conflict and depression, with lower job satisfaction scores indicating a stronger moderating effect ().

Discussion

This study examined the mediating effect of life stress and the moderated mediating effect of job satisfaction on work–family conflict and depression among working mothers during COVID-19. Based on the analysis results, this section aims to discuss how work–family conflict, life stress, and job satisfaction are related to depression in working mothers.

First, it was found that the level of depression varied significantly according to the levels of subjective health status, annual household income, and satisfaction with the husband’s contribution to household chores. This correlation between depression and subjective health status aligns with the findings of two studies, one that investigated the prevalence of depressive symptoms among Korean women and another suggesting that subjective health status is a key factor for depression among married employed women, with those perceiving their health as poor experiencing greater levels of depression.Citation25,Citation26 Subjective health perception involves a comprehensive assessment of one’s own health, taking into account medical, behavioral, and psychosocial factors.Citation27 It represents not only a complex judgment of one’s current health status but also includes an overall evaluation spanning from the past to the present.Citation27 This encompasses not just passive observations about one’s health but also expectations of active self-management.Citation27 Particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, the subjective health status of married employed women was likely influenced by pandemic-related fears, changes in daily routine, and increased childcare responsibilities at home. These factors could have impacted physical and psychosocial health, as well as approach to health management. Such shifts in health perception and management may have also contributed to a worsening of mental health, leading to increased levels of depression.

When categorizing annual household income into upper, median, and lower quartiles, the lower 25% income bracket was found to exhibit higher levels of depression compared to the upper 25%. This finding aligns with previous studies that have shown parents in poverty to experience higher levels of depression,Citation28 and that lower income is associated with an increased risk of COVID-19 mortality.Citation29 In essence, lower socio-economic status can lead to health disparities, suggesting that it contributes to mental health disparities and psychological inequality. Therefore, it is imperative to recognize and address these preventable mental health inequalities, and provide policy and institutional support aimed at achieving mental health equity.

In this study, the level of depression was also found to vary significantly according to the level of satisfaction with the husband’s contribution to household chores. In this regard, the World Health Organization (2002) reported that structural determinants, such as the societal roles of men and women, significantly impact women’s health.Citation30 Particularly in a patriarchal society like Korea, where traditional gender roles are prevalent, women often bear the primary responsibility for domestic chores, childcare, and family life, even when working outside the home, while men are more focused on their external roles.Citation31 Depression in working mothers can thus be influenced by the extent of the difficulties arising from their dual burden of work and family responsibilities, encompassing roles as a mother, housewife, and employee, as well as gender-related expectations at home. Therefore, depression in working mothers is intricately connected to the roles and interrelationships of other family members, extending beyond the individual level. The husband’s contribution to household chores is a crucial factor for women balancing professional and domestic roles. Consequently, satisfaction with the husband’s household labor contribution, rather than just the time spent, is considered an important factor in the mental health of working mothers, as it can reduce the burden of role performance at home. Therefore, addressing depression in working mothers requires a social structural perspective, focusing on reducing discriminatory perceptions of gender roles and enhancing societal responsibility and efforts.

Next, the study found that depression among Korean working mothers exhibited a positive correlation with work–family conflict and overall life stress, and a negative correlation with job satisfaction. This positive correlation between work–family conflict and depression is in line with previous research,Citation32,Citation33 suggesting that Korean working mothers, in their pursuit of perfection in both their work and home roles, face a significant dual burden, more markedly than men.Citation34 This conflict often results in heightened negative emotions, particularly when their aspirations to excel in both domains remain unfulfilled. Therefore, considering the cultural characteristics of Korea, it is imperative to launch efforts at familial and societal levels to achieve a balance in the roles played at work and home. This study specifically focused on the impact of work–family conflict in terms of fulfillment and recognition at work, satisfaction with family life, and the time spent with family. Future research should expand to consider various aspects of work–family conflict, such as “tension-based conflict arising from work-induced fatigue that hampers the performance of domestic roles” and “behavior-based conflict stemming from discrepancies in behaviors and attitudes required at work and home”.

The significant relationship between overall life stress, including job stress, and depression has been well-documented in numerous studies.Citation35–37 This aligns with the findings of the current study, where life stress was examined from various perspectives, extending beyond the dual stress of job performance and household maintenance, to include interpersonal and financial stress as well as stress coping mechanisms. The findings are particularly relevant as the survey was conducted in 2021 during COVID-19. The prolonged period of social distancing led to heightened parenting and household responsibilities,Citation38 stemming from anxiety related to childcare gaps and reliance on emergency care services. These factors likely exacerbated the various types of life stress experienced by working mothers in the context of COVID-19-related emergencies, in addition to the usual work–family conflict. Consequently, this may have led to altered stress patterns, increasing the vulnerability of working mothers to depression. Therefore, further research is necessary to explore changes in depression patterns considering the pre- and post-COVID-19 stress patterns, as well as follow-up studies to examine the impact of different types of stress on depression.

In this study, a negative correlation was observed between job satisfaction among working mothers and depression. This is consistent with previous research, which found that satisfaction with given tasks reduced negative emotional responses and the level of depression.Citation39,Citation40 Job satisfaction is defined as a positive emotional state resulting from one’s job experience and is influenced by a variety of factors.Citation41 In our analysis, we considered several related factors, including income, job security, content of work, working environment, prospects for advancement, workplace relationships, fringe benefits, and recognition of performance. Therefore, it is important to address not only personal factors but also interpersonal and environmental factors to enhance job satisfaction, as this may play a crucial role in mitigating depression.

The analysis in this study revealed the mediating effect of life stresses on the relationship between work–family conflict and depression among working mothers. It was found that a higher level of work–family conflict is associated with an increased level of depression, mediated by life stress, which is exacerbated by work-family conflict, further escalating depression. This result aligns with previous research,Citation42,Citation43 which indicated that factors such as excessive workload, poor working conditions, communication issues, and conflicts between home and work responsibilities can induce stress, subsequently affecting mental health, including depression. In this study, the level of life stress among working mothers varied based on subjective health status, satisfaction with the husband’s contribution to household chores, economic status, and type of employment. This variation suggests that these factors may influence the depression experienced by working mothers. Consequently, addressing maternal depression necessitates a comprehensive approach that considers various factors at the individual, interpersonal, and community levels.

This study also verified the moderated mediating effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between work–family conflict and depression among working mothers, with life stress acting as a mediator variable. Specifically, it was found that the strength of life stress’s mediating effect on depression driven by work–family conflict increases as job satisfaction scores decrease. Although finding comparable previous studies on the moderated mediating effect of job satisfaction was challenging, existing research has shown that job satisfaction negatively impacts life stress and depression,Citation3 and that variations in job satisfaction scores partially mediate the level of depression.Citation3,Citation14,Citation20 These results suggest that job satisfaction can be understood in the context of the existence of moderated mediating effect. Work–family conflict in working mothers leads to increased life stress and subsequent depression. Higher job satisfaction, however, can mitigate the severity of this depression. The discussion on women’s multiple roles, encompassing responsibilities in both work and family domains, is grounded in two main theoretical frameworks. Firstly, the resource drain model posits that individuals have limited mental, material, and temporal resources available for role performance.Citation44 Alternatively, the work-family enrichment model views the simultaneous performance of multiple roles as leading to psychological and physical satisfaction, thereby expanding individuals’ resources.Citation45 Therefore, to alleviate depression among working mothers, it is crucial to implement early interventions, such as screening, to prevent the exacerbation of life stress stemming from work–family conflict. Additionally, campaigns and policy measures are needed to redistribute and support the role burdens that Korean working mothers face both at work and home. Work–family conflict, characterized by role conflicts originating in the workplace, hampers the performance of home roles and is moderated by job satisfaction. Essentially, higher job satisfaction enables working mothers to overcome numerous workplace challenges. This is particularly evident among the 70% of female healthcare workers during COVID-19, who faced increased risks of infection and unemployment due to layoffs, recommended resignations, and forced leaves.Citation9 In such dynamic job situations, job satisfaction, including employment stability, income, work environment, and job content, likely served as a buffer in reducing depression. Therefore, in response to disaster situations, national policies focusing on employment stability and income are essential to address the depression experienced by married employed women.

This study utilized secondary data from Wave 8 of the Korean Longitudinal Survey of Women and Families (2021). While the results offer valuable insights, they are subject to several limitations. First, considering that the survey was conducted during COVID-19, the causal relationships between the primary variables remain ambiguous. This uncertainty underscores the need for comparative research to examine work modes and household labor patterns before and after the pandemic’s onset. Second, the focus on working mothers may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research should encompass various employment types to comprehensively assess depression levels. Third, this study’s sole reliance on depression as a mental health measure may overlook other pertinent indicators, such as anxiety and life satisfaction. Despite these limitations, the study’s significance lies in providing foundational data that contributes to the development of systems for prevention, preparedness, and response to mental health challenges in disaster scenarios, like the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly focusing on the depression experiences of working mothers and identification of related factors.

Conclusion

As participation in economic activities among married women increases in OECD countries, including South Korea, interest in maternal mental health, particularly regarding depression proportionally increased. Consequently, this study aimed to comprehensively examine the moderated mediating effect of job satisfaction on the pathway through which work–family conflict affects depression via life stress, with a focus on working mothers in South Korea, where a patriarchal culture continues to prevail. To achieve this, a three-phase analysis was conducted on data extracted from Wave 8 of the Korean Longitudinal Survey of Women and Families conducted in 2021. Initially, 1325 married employed women aged 26–55 with cohabiting children (referred to as “working mothers”) were selected as subjects. The study then examined the mediating effect of life stress in the causal relationship between work–family conflict and depression. Lastly, it examined the moderated mediating effect of job satisfaction in moderating the mediation effect of life stress in the causal relationship between work–family conflict and depression The analysis revealed a significant mediating effect of life stress on the impact of work–family conflict on depression, as well as a significant interaction between life stress and job satisfaction, thereby confirming the moderated mediating effect of job satisfaction. Based on these findings, the study proposes various intervention strategies at individual, interpersonal, organizational, and community levels to enhance the mental health of married employed women by reducing work–family conflict and life stress, and increase job satisfaction.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Acknowledgments

Hyo Sung Cha and Jin Pyo Lee are co-first authors for this study. The authors would like to express their gratitude to the working mothers who participated in the data collection.

References

- OECD. Employment: labour force participation rate, by sex v age group; 2023. Available from: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=STLABOUR#. Accessed August 4, 2023.

- Statistics Korea. Supplementary Results of the Local Area Labour Force Survey in the First Half of 2022 (Married Women’s Employment Status); 2022. Abailable from: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a20105050000&bid=11735&act=view&list_no=422060. Accessed August 4, 2023.

- Choi EJ, Kim CK. Mediating effects of job satisfaction in daily stress on depression: difference of married working women’s academic background. Women’s Studies. 2017;3:85–111.

- Frone MR, Russell M, Cooper ML. Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: testing a model of the work-family interface. J Appl Psychol. 1992;77(1):65–78. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.77.1.65

- Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad Manage Rev. 1985;10(1):76–88. doi:10.5465/amr.1985.4277352

- Yang SN, Shin CS. Work-family conflicts: challenges of working mothers with young children. Health Soc Welfare Rev. 2011;31(3):70–103. doi:10.15709/hswr.2011.31.3.70

- Park JM, Kim YJ, Chin MJ. Changes of work-parenting conflict among employed mothers with elementary school students using the multi-level growth model. J Fam Better Life. 2022;40(4):119–131. doi:10.7466/JFBL.2022.40.4.11

- Sung JH, Kim CK. 2019 The mediation effects of work-family reconciliation conflicts on the influence of family value orientations to depression of working women: longitudinal mediation analysis using multivariate Latent growth curve modeling and autoregressive cross-lagged modeling. Women’s Studies. 2019;101(2):111–133. doi:10.33949/tws.2019.101.2.004

- Ko EJ. A Study on the system reinforcement plan to complement the vulnerability of women’s employment due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Legislation. 2021;695:41–66. doi:10.23028/moleg.2021.695.002

- Eun GS. COVID-19 pandemic and changes in child care. Labor Rev. 2020;11:35–49.

- Kim JY, Jung GH, Kim JH. Work–family conflict and depressive symptoms of married working women in Korea: the role of marriage satisfaction and organizational gender discrimination climate. SAGE Open Nurs. 2023;9:23779608231196841. PMID: 37675149. doi:10.1177/23779608231196841

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer publishing company; 1984.

- Cordner G, Scarborough K. Information sharing: exploring the intersection of policing with national and military intelligence. Homeland Security Affairs. 2010;6(1):1–19.

- Park SM, Han SH. Influences of work and family on the married female workers’ health. J Popul Assoc Korea. 2004;27:2.

- Chandola T, Martikainen P, Bartley M, et al. Does conflict between home and work explain the effect of multiple roles on mental health? A comparative study of Finland, Japan, and the UK. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33(4):884–893. doi:10.1093/ije/dyh155

- Greenhaus JH, Allen TD, Spector PE. Health-consequences of work–family conflict: the dark side of the work–family interface. In: Research in Occupational Stress and Well Being. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. E book; 2006:61–98. doi:10.1016/S1479-3555(05)05002-X

- Kalliath P, Hughes M, Newcombe P. When work and family are in conflict: impact on psychological strain experienced by social workers in Australia. Australian Social Work. 2012;65(3):355–371. doi:10.1080/0312407X.2011.625035

- Zhou S, Da S, Guo H, Zhang X. Work-family conflict and mental health among female employees: a sequential mediation model via negative affect and perceived stress. Front Psychol. 2018;17(9):544. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00544

- Byron K. A meta-analytic review of work–family conflict and its antecedents. J vocat Behav. 2005;67(2):169–198. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2004.08.009

- Kim DH, Song IH. The influence of married women’s work-family conflict and family-work conflict on depression: analysis of the mediating effect of job satisfaction. J Soc Sci. 2021;60(2):357–382. doi:10.22418/JSS.2021.8.60.2.357ISSN

- Ju YJ, Park EC, Ju HJ, et al. (2018) The influence of family stress and conflict on depressive symptoms among working married women: a longitudinal study. Health Care Women Int. 2018;39(3):275–288. doi:10.1080/07399332.2017.1397672

- Joo JJ, Lee DS, Cho SM, et al. Korean Longitudinal Survey of Women & Family: The 2021 Annual Report. Seoul: Korea Women’s Development Institute; 2022.

- Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. 2nd ed. New York (NY): The Guilford Press; 2018:393–468.

- Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. 1st ed. Paju: Shinyoungsa; 2015. 1–486.

- Shin KR. Depression Among Korean Women. J Kor Acad Nurs. 2001;31(3):391–400.

- Kim SK, Park SY, Rhee HS. The effect of work-family conflict on depression in married working women. J Digit Converg. 2017;15(3):267–275. doi:10.14400/JDC.2017.15.3.267

- Nam SI, Choi KH, Yi HJ. Self-perceived health status, depression, and suicidal behavior among people with diabetes. Kor J Soc Welfare Stud. 2014;45(1):231–254.

- Noh HJ. A longitudinal study of changes in depression level in parents of households with children after COVID-19: focusing on poverty. Health Soc Welfare Rev. 2022;42(2):199–219.

- Nam JH, Lee RH. Is the COVID-19’s impact equal to all in south korea? - Focusing on the effects on income and poverty by employment status. Kor J Soc Welfare Studi. 2020;45(1):231–254. doi:10.20970/kasw.2020.72.4.008

- World Health Organization. The world health report 2001: mental health: new understanding, new hope; 2002.

- Lee JM, Song IH. Effects of poverty experience and perceived traditional gender roles on married women’s depression. Soc Sci Rev. 2021;52(2):139–161. doi:10.31502/SSRI.52.2.7

- Fujimoto T, Shinohara SK, Oohira T. Work–family conflict and depression for employed husbands and wives in Japan: moderating roles of self and spousal role involvement. Fam Relation Fam Respon Health Iss. 2014;8:135–162.

- O’Brien KM, Ganginis Del Pino HV, Yoo SK, Cinamon RG, Han YJ. Work, family, support, and depression: employed mothers in Israel, Korea, and the United States. J Couns Psychol. 2014;61(3):461–472. doi:10.1037/a0036339

- Yoo SK, Lim JS, Son EY. Concept mapping of work-family reconciliation in Korean working mothers. Kor J Counsel. 2016;17(6):475–498. doi:10.15703/kjc.17.6.201612.475

- Griffin JM, Fuhrer R, Stansfeld SA, Marmot M. The importance of low control at work and home on depression and anxiety: do these effects vary by gender and social class? Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:783–798. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00109-5

- Iacovides A, Fountoulakis KN, Kaprinis S, Kaprinis G. The relationship between job stress, burnout and clinical depression. J Affect Disord. 2003;75:209–221. doi:10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00101-5

- Lee EY, Lee JY. The relationship between stress and depression of COVID-19 perceived by married women: focusing on the mediating effect of family cohesion and entrapment. J Hum Soc Sci. 2022;13(6):2855–2869. doi:10.22143/HSS21.13.6.196

- Talati AN, Manuck TA. 1023 The evolution of maternal stressors and coping strategies during the COVID19 pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224(2):S633. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.12.1048

- Stansfeld S, Candy B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health--a meta-analytic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(6):443–462. doi:10.5271/sjweh.1050

- Griffin ML, Hogan NL, Lambert EG, Tucker-Gail KA, Baker DN. Job involvement, job stress, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment and the burnout of correctional staff. Criml Justice Behav. 2010;37(2):239–255. doi:10.1177/0093854809351

- Szilagyi AD, Wallace MJ. Intragroup behavior. In: Organizational Behavior and Performance. 4th ed. Glenview, Illinois: Scott, Foresman and Compan; 1987.

- Pikhart H, Bobak M, Pajak A, et al. Psychosocial factors at work and depression in three countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:1475–1482. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00350-2

- Hammer LB, Cullen JC, Neal MB, Sinclair RR, Shafiro MV. The longitudinal effects of work-family conflict and positive spillover on depression symptoms among dual-earner couples. J Occup Health Psychol. 2005;10(2):138–154. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.138

- Edwards JR, Rothbard NP. Mechanisms linking work and family: clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Acad Manage Rev. 2000;25(1):178–199. doi:10.2307/259269

- Greenhaus JH, Powell GN. When work and family are allies: a theory of work-family enrichment. Acad Manage Rev. 2006;31(1):72–92. doi:10.5465/amr.2006.19379625