Abstract

Since the implementation of effective combination antiretroviral therapy, HIV infection has been transformed from a life-threatening condition into a chronic disease. As people with HIV are living longer, aging and its associated manifestations have become key priorities as part of HIV care. For women with HIV, menopause is an important part of aging to consider. Women currently represent more than one half of HIV-positive individuals worldwide. Given the vast proportion of women living with HIV who are, and will be, transitioning through age-related life events, the interaction between HIV infection and menopause must be addressed by clinicians and researchers. Menopause is a major clinical event that is universally experienced by women, but affects each individual woman uniquely. This transitional time in women’s lives has various clinical implications including physical and psychological symptoms, and accelerated development and progression of other age-related comorbidities, particularly cardiovascular disease, neurocognitive dysfunction, and bone mineral disease; all of which are potentially heightened by HIV or its treatment. Furthermore, within the context of HIV, there are the additional considerations of HIV acquisition and transmission risk, progression of infection, changes in antiretroviral pharmacokinetics, response, and toxicities. These menopausal manifestations and complications must be managed concurrently with HIV, while keeping in mind the potential influence of menopause on the prognosis of HIV infection itself. This results in additional complexity for clinicians caring for women living with HIV, and highlights the shifting paradigm in HIV care that must accompany this aging and evolving population.

Introduction

The nature of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) pandemic has changed dramatically since discovered over 33 years ago. Extraordinary progress has been achieved in the management of HIV with the advent of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), which can effectively control viral replication, and has resulted in remarkable reductions in HIV-associated morbidity and mortality.Citation1–Citation4 In today’s landscape, the reported life expectancy for a person newly diagnosed with HIV, in the context of access to cART, can approach that of the general population.Citation5 One of the greatest medical victories of this generation has been the transformation of HIV from an acute, life-limiting infection to a chronic disease with incredibly effective treatment.Citation2

In addition to the marked changes in morbidity and life expectancy, the evolving epidemiology of HIV infection has seen an escalating impact on women. Current data suggest that of the 35 million people living with HIV worldwide, 52% are women. The proportion of infected women varies geographically:Citation6 in Sub-Saharan Africa, women represent approximately 57% of those with HIV,Citation6 while in developed countries such as Canada and the USA, this proportion is markedly lower at 22% to 23%.Citation7,Citation8 The vulnerability that women experience related to HIV, with respect to both the causes and consequences of infection, is a complex phenomenon resulting from biological and sociopolitical inequities.Citation6,Citation7

In earlier stages of the pandemic, the principal concerns surrounding HIV infection in women centered on sexual and reproductive health, largely due to the high rates of HIV infection among women of reproductive age and the risks of vertical transmission. However, in the current era of increasingly accessible and efficacious cART, and longer life expectancies, HIV in the context of increased age becomes a key clinical consideration.Citation9,Citation10 In 2011, 26% of individuals living with HIV in the USA were greater than 55 years of age.Citation11 It is anticipated that by 2020, up to 70% of HIV infection will be in patients over the age of 70 years.Citation12 Five percent of new infections in the USA are estimated to occur in those greater than 55 years of age, and older Americans are more likely to present in later stages of the disease.Citation11 Consequently, issues pertaining to age-related comorbidities and other life events, including menopause, represent an emerging aspect of HIV care.Citation9,Citation13

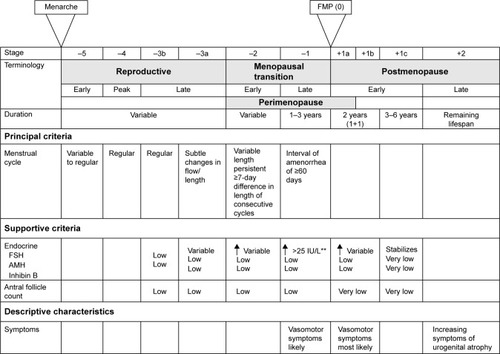

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines natural menopause as the permanent cessation of menses. Specifically, this refers to a period of amenorrhea of at least 12 months that is due to the loss of ovarian follicular activity, and occurs in the absence of any other physiologic or pathologic process.Citation14,Citation15 This is in contrast to other forms of menopause, in which an alternative etiology can be identified ().Citation15 Natural menopause typically occurs between the ages of 50 and 52 years in developed nations, but there is considerable geographic variation with respect to age of onset throughout the world.Citation16–Citation20 As hormone production in the ovaries declines with age, and eventually ceases entirely, the menopausal transition occurs in three stages ().Citation21 Menopause is a complex clinical process that is uniquely experienced by each woman, and is associated with various biological and psychosocial changes including alterations in bone health, cognition, risk of other age-related comorbidities, and an array of physical and psychological symptoms.Citation13,Citation22–Citation27 Women around the world from various cultural groups, races, and religions have been found to report diverse biological, sociocultural, and psychological factors that influence their experiences and perceptions related to menopause.Citation23,Citation28,Citation29 In women living with HIV, an intricate relationship between HIV and menopause appears to exist in that HIV may influence the natural history, experience, and complications of menopause, while menopause itself could potentially influence the course of HIV infection.Citation28 This bidirectional relationship between HIV infection and menopause confers an additional layer of complexity to the ongoing management of HIV-infected women as they age, and presents new and vaguely understood challenges for clinicians.

Figure 1 The stages of the menopausal transition in women.

Abbreviations: FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; FMP, final menstrual period; AMH, anti-Mullerian hormone.

Table 1 Classification of menopausal statesCitation14,Citation15,Citation22

Impact of menopause on HIV infection

Aging, menopause, and transmission of HIV

As individuals age, they continue to represent an important, but often overlooked, population at risk of acquiring HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).Citation11,Citation30 This has implications both from an individual and public health perspective. In 2010, approximately 5% of new HIV diagnoses in the USA occurred in adults greater than 55 years of age.Citation11 Furthermore, older adults diagnosed with HIV tend to be diagnosed later on in the course of their disease, which can affect severity of immune dysfunction, response to treatment, and survival.Citation11,Citation31–Citation34 In the USA in 2013, 27% of AIDS diagnoses, the most advanced stage of HIV infection,Citation35 occurred in patients greater than 50 years of age.Citation11 Additionally, while 98% of patients diagnosed with HIV between the ages of 20–29 years in the USA will survive beyond 12 months, the prognosis for new diagnoses in older adults is substantially lower. The proportion of those who survive for more than 1 year after diagnosis declines with increasing age, from 86% among those diagnosed at ages 50–59 years, to 82% among those aged 60–64 years, and 73% in those diagnosed at age 65 years and older.Citation11

The primary mode of HIV transmission and acquisition in people over the age of 50 years is through sexual contact.Citation11 While sexual activity does decline with age, many older individuals will continue to remain sexually active after the age of 50 years.Citation11,Citation30,Citation36–Citation38 In an assessment of sexual behavior in adults in the USA, 59% of women aged 55–59 years had engaged in sexual activity in the past year.Citation30,Citation39 A similar study of adults over the age of 60 years in the USA found that 71% of men and 51% of women remained sexually active.Citation30,Citation40 Furthermore, 30% of women in their 70s and 20% of those in their 80s engaged in some measure of sexual activity.Citation30,Citation40 Older adults will report sexual activity regardless of marital status, and may continue to engage in diverse sexual activities including vaginal-penile intercourse, oral sex, and receptive and insertive anal intercourse.Citation30,Citation39–Citation42 These individuals, therefore, retain traditional risk factors for HIV acquisition. Condom use is an effective measure to prevent sexual transmission of HIV. However, with reduced fertility in the later years, condom use has been found to decline.Citation43–Citation46 The lack of condom use in older adults may be further explained by the misperception that they are at minimal risk of contracting HIV and other STIs.Citation37,Citation47 In fact, in an analysis of responses from 12,366 adults aged 50 years and older in the 2009 National Health Interview Survey in the USA, 84.1% believed they had zero chance of becoming infected with HIV.Citation47 This underestimation of HIV-acquisition risk in older patients also extends to their physicians.Citation11,Citation37,Citation48–Citation50 For example, one study demonstrated that among individuals aged 58–93 years, of whom 57% were sexually active after the age of 60 years, 11% had received STI/HIV counselling from their physicians, and only 4% had ever been offered an HIV test.Citation37 For postmenopausal women specifically, physiologic changes such as vaginal dryness, vaginal atrophy, and decreased libido likely contribute to reduced sexual activity. However, these changes in vaginal tissue may also increase biologic predisposition to acquiring HIV infection, even with reduced sexual contact.Citation6,Citation9,Citation11,Citation51,Citation52 Therefore, it is important that physicians and other health care providers continue to discuss sexual behaviors with their aging patients, and counsel them on strategies to prevent HIV and other STIs. It is equally critical that HIV testing be offered to older adults who remain sexually active.

Continuation of sexual activity into older age has also been demonstrated in the HIV-positive population.Citation32,Citation36,Citation53 In an assessment of women aged 40–57 years in the Women’s Interagency Health Study (WIHS), a prospective cohort study of HIV-positive and -negative women in the USA, 73%–74% of HIV-positive women remained sexually active.Citation36 This included women with detectable and undetectable viral loads.Citation36 With increasing age, there were similar patterns of reduced sexual activity between sero-positive and sero-negative women in the cohort.Citation36 Similarly, a study of 123 HIV-positive women over the age of 50 years in the UK found that 60% remained sexually active.Citation32 Unfortunately, up to one-third of older, HIV-infected patients report having unprotected intercourse, including with serodiscordant partners.Citation36,Citation53 While limited reproductive potential and underestimation of STI acquisition risk have been postulated as the reasons for low condom use in older adults, additional factors among people with HIV, including fear of HIV-related stigma and forced disclosure of HIV status, may also contribute to suboptimal condom use.Citation11,Citation43,Citation44,Citation54–Citation56 Studies exploring condom use among postmenopausal women with HIV have suggested that approximately 70% use condoms.Citation54,Citation55,Citation57 In the WIHS, menopausal status itself was not found to impact condom use in HIV-positive women; however, overall condom use was reported in only 74% of premenopausal and 70% of postmenopausal women.Citation54 When adjustments for sero-status were performed in a multivariable model, no significant difference in condom use was found between the HIV-positive and HIV-negative women.Citation54

In addition to the aforementioned need for improved condom use in older adults, prevention strategies specific to HIV-positive individuals also include “treatment as prevention”. This strategy is garnering increased attention in light of the evidence showing that there is minimal risk of HIV transmission from people on cART with fully suppressed viral loads.Citation58,Citation59 Treatment as prevention can be an important HIV prevention strategy among older adults. However, clinicians should promote safer sex practices in all of their adult patients for the prevention of other STIs.

Studies have also attempted to determine if menopausal status affects cervical shedding of the HIV virus, thereby increasing the risk of sexual transmission. However, these results have been inconsistent. An in vitro study of ectocervical tissues from pre- (<45 years) and postmenopausal (>55 years of age) women, in which tissue samples were ex vivo infected with HIV-1 virus after hysterectomy, found higher levels of viral transcription in postmenopausal vs premenopausal samples.Citation60 This could potentially have clinical implications if recently infected postmenopausal women, in the setting of already reduced condom use, are more likely to transmit the virus to others because of higher cervical viral shedding. However, this finding has not been replicated in any in vivo studies. Melo et alCitation61 performed a cross-sectional study of pre- and postmenopausal, HIV-positive women in Brazil. They found no association between menopausal status and in vivo cervico-vaginal viral shedding; rather, degree of shedding was, as expected, associated with plasma viral load and vaginal pH.Citation61 Once again, this emphasizes the importance of antiretroviral treatment and virologic suppression in the HIV prevention armamentarium.

Menopause and progression of HIV

As women with HIV transition through menopause, the progression of their infection and response to treatment in the setting of altered reproductive hormones is a key consideration. Older patients with HIV who are not on cART have lower baseline CD4 counts than younger patients.Citation31 A component of this is likely related to age, as lymphocyte subsets, including CD4 counts, have been found to decrease with increasing age in non-HIV-infected adults.Citation62 In those with HIV, timing of diagnosis is also a potential contributor. Older individuals are less likely to be tested for HIV and are more likely to be diagnosed with HIV later on in the course of the disease.Citation11,Citation31 This can result in lower CD4 set points at the time of antiretroviral initiation and a blunted response to treatment.Citation11,Citation28,Citation31,Citation63–Citation65 However, menopausal status itself may also contribute to lower CD4 counts.Citation28 With age and menopause, quantity of thymic tissue is reduced, which has implications for immunologic status.Citation28 In a study of 382 HIV-positive women not on cART, with a known period of sero-conversion, a regression analysis modeling CD4 decline found a trend for postmenopausal women having lower CD4 counts 3 years after sero-conversion compared to premenopausal women (333 cells/μL vs 399 cells/μL, P=0.09).Citation66 However, this result did not achieve statistical significance and furthermore, there was no difference in the rate of CD4 decline.Citation66

More recent studies have generally yielded promising results, finding that menopausal status itself does not influence response to antiretroviral treatment.Citation67,Citation68 In 267 treatment-naïve women living with HIV, 47 of whom were postmenopausal, CD4 and viral load response to antiretroviral initiation did not differ between those who were pre- and postmenopausal.Citation67 Postmenopausal women were able to maintain viral suppression through a 96-week follow-up period.Citation67 Similarly, in a prospective cohort study of 383 antiretroviral-naïve, HIV-infected women in Brazil (85% premenopausal and 15% postmenopausal), menopausal status had no effect on treatment response at 24 months post-initiation of therapy.Citation68 Pre- and postmenopausal women, with similar baseline CD4 counts (231 cells/mm3 compared to 208 cells/mm3, P=0.14), were equally likely to achieve virologic suppression. Interestingly, postmenopausal women had a lower median CD4 response than premenopausal women at the 24-month postantiretroviral therapy (ART) time point (184 cells/mm3 vs 273 cells/mm3, P=0.02); however, when this analysis was restricted to the women who achieved a viral load <400 copies/mL, there was no longer a difference in CD4 response (P=0.27).Citation68

With increased age and menopause, alterations in drug pharmacokinetics may result from changes in volume of distribution and renal and hepatic clearance, which may further have implications for treatment responses and toxicities in elderly patients.Citation69 Gervasoni et al attempted to determine if antiretroviral levels were affected by menopause. They found that between 28 pre- and 22 postmenopausal women, there was no difference in plasma levels of tenofovir (TDF), a commonly used nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI).Citation70 Similarly, Cottrell et al found no difference in steady-state area under the curve plasma levels of the integrase inhibitor, raltegravir, between HIV-positive pre- vs postmenopausal women.Citation71 Nevertheless, increased plasma drug concentrations are known to occur in elderly patients,Citation72 and clearly need to be considered in the management of menopausal HIV-positive women as they could be at higher risk of drug toxicities than their younger, premenopausal counterparts.Citation73 However, an independent effect of menopausal status on antiretroviral pharmacokinetics has not been established.

Impact of HIV infection on menopause

Age of menopause

Natural menopause typically occurs between the ages of 50 and 52 years.Citation16,Citation17 However, average age of menopause displays significant country-to-country variation and therefore, an examination of the age of onset of menopause in any subpopulation requires comparison to the national average.Citation18,Citation20 Most studies operationalize the term “early menopause” as menopause occurring between the ages of 40 and 45 years,Citation13–Citation15,Citation19,Citation22,Citation74 and premature menopause (sometimes referred to as premature ovarian failure) as menopause occurring before the age of 40 years ().Citation14,Citation15,Citation22 Early and premature menopause have important clinical implications. They are linked to alterations in mood and sexual function, declines in quality of life, development of comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and fragility fractures, and have been associated with earlier mortality.Citation22,Citation75–Citation79 Therefore, an understanding of which populations are at increased risk of early and premature menopause is important for the counseling and management of female patients, as well as for the assessment of hormone therapy (HT) initiation if clinically indicated.Citation9

Within the HIV-positive community, several reports have demonstrated that the average age of menopause is lower than the general population, and that women with HIV are at higher risk of developing early and premature menopause ().Citation13,Citation19,Citation32,Citation80–Citation84 In a study of 268 women living with HIV in Thailand, the average age of menopause was 2.2 years earlier than the national average.Citation82 In this study, the earlier age of menopause occurred independent of immunologic (CD4 count and viral load) and socio-demographic variables (age of menarche, marital status, parity, education, or income). Calvet et alCitation19 assessed 667 HIV-positive women in Brazil, and found that median age of menopause was 48 years (interquartile range: 45–50 years), which is lower than the average age of menopause in the general population. Additionally, 27% of women in this study experienced menopause before 45 years of age.Citation19 In the USA, age of menopause onset in women living with HIV has ranged from 46 to 50 years across various studies.Citation13,Citation80,Citation81,Citation83,Citation84 Fantry et al demonstrated that in 120 HIV-positive women, 35% reported early menopause,Citation13 while Schoenbaum et al found that 26% of HIV-positive women in New York experienced premature menopause, significantly higher than the 10% reported in the HIV-negative counterparts.Citation81 Conversely, other studies have failed to demonstrate an earlier age of menopause when comparing HIV-positive and HIV-negative women.Citation74,Citation83,Citation85 In a prospective cohort study of women living with HIV in France, the median age of onset of menopause was 49 years (interquartile range: 40–50 years), which was comparable to the general population in France.Citation74,Citation86 However, it is important to note that in this study, 22% of women reported early menopause and 12% experienced premature menopause.Citation74 Cejtin et al performed a study of 1,335 women in the WIHS, and found no difference in the mean age of menopause between sero-positive (47.7 years) and sero-negative women (48 years).Citation83,Citation87 However, in a follow-up study of 1,431 women in the same cohort, the median age of menopause onset in the entire sample was 47 years, which is lower than the national average in the USA.Citation85 This raises the possibility that the entire patient population was at risk of early menopause, thereby impairing the ability to demonstrate a difference between those with and without HIV infection. Alternatively, this study has been the only one to examine the age of menopause with a biochemical confirmation of ovarian failure, which may result in a more accurate assessment of menopause than self-report. Fantry et al also failed to show an earlier age of menopause in HIV-positive women in Baltimore.Citation13 In this study, median age of menopause was 50 years (95% confidence interval 49–53); however, 55% of menopausal women reported early menopause (<45 years), and 35% reported premature ovarian failure (<40 years), which is substantially higher than the 5% and 1% of early menopause and premature ovarian failure reported in the general population, respectively.Citation13,Citation22 Unfortunately, this study did not enroll an HIV-negative control group for comparison, and the small sample size limits the interpretation of these proportions.

Table 2 Summary of studies assessing age of menopause in women with HIV

The association between HIV-positivity and early menopause is likely multifactorial and subject to confounding by other factors, which contributes to variation in patient populations, and limits the ability to compare studies. It has been consistently shown that several risk factors for early menopause, including African–American ethnicity,Citation74,Citation81,Citation85,Citation88–Citation90 smoking,Citation19,Citation81,Citation84 and substance use,Citation74,Citation81 are more prevalent in HIV-positive patients and can affect the age of menopause.Citation28 Additionally, the assessment of age of menopause is complicated by the subjective nature of the diagnosis. The WHO defines menopause based on a self-report of cessation of menstruation, but does not require an evaluation of any biochemical parameters, such as reproductive hormone levels.Citation14,Citation15 While this may be appropriate for the general population, it is potentially problematic in women living with HIV. In this population, the higher risk of menstrual irregularity, anovulation, and amenorrhea confounds the ability to accurately assess onset of menopause.Citation18,Citation85,Citation91–Citation93 Cejtin et al demonstrated this phenomenon in the aforementioned WIHS study. In this cohort, being HIV-positive was associated with a nearly twofold increased risk of having a period of amenorrhea lasting ≥12 months.Citation85 Furthermore, of the 136 women with more than 1 year of amenorrhea, less than half (46.7%) had biochemical evidence of menopause with an elevated follicle-stimulating hormone, compared to 68.8% in the HIV-negative group. This indicated an independently higher risk for women with HIV to have amenorrhea in the absence of menopause, with an odds ratio of 3.16.Citation85 Amenorrhea without menopause was more common in those with lower albumin, history of AIDS-defining illness, reduced income, and non-Hispanic ethnicity, highlighting a potential contribution of more severe illness and poorer nutritional status.Citation85 Similarly, in a study of stored serum samples from HIV-positive women aged 20–42 years, 48% demonstrated evidence of anovulation, which was associated with lower CD4 counts.Citation91 Therefore, in women with HIV, biochemical confirmation of menopause may be warranted, as this may have implications for contraception counselling, as well as screening for and management of menopause-associated comorbidities.Citation85

The influence of immunologic status and virologic control on risk and age of menopause among women with HIV has been inconsistent. While some studies have demonstrated a correlation between lower CD4 count and higher risk of early menopause,Citation19,Citation74,Citation81,Citation83 other studies have failed to confirm this relationship.Citation13,Citation85

Symptoms of menopause

The exact role and impact of HIV infection on the experience of menopause is far from certain. Women living with HIV may report a different experience of and attitude toward menopause. Menopausal symptoms are contextually dependent, subject to influence by an array of biological, psychosocial and cultural factors, and are uniquely experienced by each individual woman.Citation25–Citation29,Citation80,Citation94 HIV-positive women may be more likely to experience menopausal symptoms than those without HIV infection; however, a consistent association has not been found. Furthermore, defining the relationship between HIV and menopausal symptoms is complicated by the difficulty in reliably distinguishing between symptomatology due to aging and menopause vs that due to HIV infection itself and the effects of ART.Citation85,Citation95,Citation96

There has been some indication that women with HIV may be more likely to experience vasomotor symptoms when transitioning through menopause ().Citation80,Citation82,Citation94,Citation97 In their study of HIV-positive Thai women, Boonyanurak et al found that postmenopausal status was, not unexpectedly, associated with more vasomotor night sweats and change in sexual desire when compared to premenopausal women with HIV.Citation82 However, all women in this study were HIV-positive. Therefore, the study findings indicate that women with HIV still experience the typical symptoms of menopause, but does not allow for a differentiation of symptom experience between those with and without infection. On the other hand, Ferreira et al did find that HIV infection was independently associated with a 65% higher risk of reporting menopausal symptoms.Citation80 Similarly, in 66 women living in the USA, those with HIV reported a greater severity of hot flashes when compared to women without HIV.Citation97 However, these findings have not been consistently reported in the literature, and there have been several studies that have not demonstrated a relationship between HIV-positivity and vasomotor symptoms.Citation27,Citation94,Citation98–Citation101 Lui-Filho et al found that vasomotor symptoms were associated with menopausal status, as expected, but were no different between sero-positive and sero-negative women in Brazil.Citation27 Additionally, a comparison between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women living in New York City found no difference in the prevalence of hot flashes or vaginal dryness between the two groups.Citation98 These contradictory findings also extend to the relationship between immunologic status and experience of symptoms. While one study has found that lower CD4 counts are associated with increased vasomotor symptoms,Citation94 others have found no associationCitation80,Citation82 or even the opposite in that symptoms were more prevalent in women with higher CD4 counts.Citation84 Therefore, a clear association has not been established.

Table 3 Summary of studies assessing menopausal symptoms in women with HIV

Mental health considerations in the postmenopausal period are also of particular importance. However, the relationship between mental health, HIV infection, and other socio-demographic confounders presents a multifaceted and complex picture. The menopausal transition itself, and the accompanying symptoms, regardless of HIV sero-status, can be associated with sleep disturbances, depression, and changes in cognition.Citation94,Citation102 Several studies have reported worsened mental health outcomes among women with HIV in the postmenopausal period, including panic attacks, depressive symptoms, and sleep disturbances.Citation80,Citation97,Citation99,Citation102–Citation105 However, other studies have failed to replicate this finding.Citation27,Citation82,Citation99,Citation102,Citation106,Citation107 Depressive symptoms are also more likely to occur in women who are experiencing menopausal symptomsCitation94,Citation102,Citation108–Citation110 and have been associated with reduced quality of life,Citation25,Citation111 a negative attitude towards menopause,Citation28,Citation112 and decreased adherence to therapy.Citation113,Citation114

The impact of menopause and depressive symptoms on cognition is also an important consideration in HIV, as the virus is found in central nervous system tissue and is associated with the HIV-associated neurological disorders.Citation115,Citation116 Studies have suggested that compared to men, women with HIV are more likely to have lower education levels and increased difficulty accessing ART, which may result in their being more vulnerable to the development of HIV-associated neurological disorders and dementia.Citation107,Citation116,Citation117 In a study of 41 women (20 HIV-positive and 21 HIV-negative) in Italy aged 65 years and older, women with HIV had worse performance on tests of executive function, processing speed, and verbal learning than age-matched, HIV-negative controls.Citation107 Depression and anxiety can exacerbate these cognitive changes.Citation99,Citation115,Citation116 In a study of 708 HIV-positive and 278 HIV-negative women living in the USA, women with HIV had a poorer performance on tests of verbal learning than those without HIV. While this study did not find an independent association between menopausal status and cognitive performance, verbal learning was negatively influenced by symptoms of anxiety, and was likely also influenced by poorer socioeconomic status.Citation99 Therefore, if women with HIV are truly more likely to experience depression and anxiety, either independently or due to the menopausal transition and its myriad of symptoms and complications, cognitive function may also be affected.

These differential and contradictory findings with respect to HIV and menopausal symptoms may be related to differences in the study populations, which makes a direct comparison between study results difficult. Differences in socioeconomic status and ethnicity have been shown to influence symptoms and attitudes toward menopause and are likely contributing to the variation in findings.Citation80,Citation94,Citation109,Citation118 Women of African–American ethnicity have been found to report more symptoms of menopause when compared to Caucasian and Hispanic women.Citation101 Additionally, lower education, poverty, and receipt of social assistance are associated with more menopausal symptoms and may be more prevalent in the HIV-positive community.Citation27,Citation80,Citation94,Citation109,Citation118 Method of menopausal symptom assessment is also a key consideration. It has been found that women with HIV may be unable to distinguish between symptoms related to menopause vs those related to HIV itself and ART.Citation95,Citation98 They are also less likely than HIV-negative women to have knowledge of what to expect when going through the menopausal transition, which could potentially influence their expectations of aging and have a negative impact on mood if they do not understand why certain symptoms are occurring.Citation95,Citation98 These findings may be related to the earlier age of menopause in HIV-infection, in which case symptoms might be misattributed to HIV itself because menopause would be unexpected.Citation98 Lower education and socioeconomic status in certain study populations may also partially explain these misperceptions.Citation95 Therefore, it is important for clinicians to discuss aging and menopause with their HIV-positive patients, so that they can be better prepared for any changes or symptoms they might develop.

Hormone therapy has been shown to have beneficial effects in certain women with menopause, particularly with respect to vasomotor symptoms and bone health.Citation84,Citation119 However, practitioners may be reluctant to provide HT to women with HIV for fear of worsening HIV status, or due to concerns regarding toxicity, increased pill burden, and/or drug–drug interactions with ART.Citation84 Consequently, rates of HT use in HIV-positive women are typically very low at approximately 10% or less.Citation13,Citation32,Citation84,Citation120 There have been no published studies examining the utility and/or safety of HT in women with HIV, and there is limited data on use of HT in women on cART. Though there may be drug–drug interactions between HT and some protease inhibitors (PIs) and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), including fosamprenavir (PI) and efavirenz (NNRTI), newer antiretroviral agents likely do not possess the same pharmacologic concerns.Citation9 Prolonged HT has been associated with other medical complications such as breast cancer, thromboembolic disease, and cardiovascular disease. Therefore, current HIV primary care guidelines are similar to those for the general population and suggest that HT, if used, should be provided at the lowest effective dose and for a limited time only.Citation121 However, HT is likely being underutilized in women with HIV and should be considered for those who might otherwise benefit due to severe menopausal symptoms, as long as there are no contraindications to therapy.Citation32

Bone mineral density (BMD)

The higher prevalence of amenorrhea and earlier age of menopause that accompany HIV infection in women predisposes them to earlier and more severe bone loss when compared to those without HIV. Osteoporosis, a disorder characterized by decreases in bone density and quality and increased susceptibility to fracture, represents a significant global health burden, particularly for postmenopausal women.Citation120,Citation122 The WHO operationally defines osteoporosis as having a BMD score of 2.5 or more standard deviations below the mean for young, healthy women (ie, a T-score ≤2.5).Citation122–Citation124 Osteoporosis affects more than 75 million people in developed countries; globally, it is responsible for more than 8.9 million fractures per year,Citation124 and leads to reductions in quality of life, and a higher risk of morbidity and mortality.Citation120,Citation125,Citation126 While increased age and postmenopausal status are the two most important factors predisposing to low BMD and osteoporosis, a variety of additional factors, including lifestyle behaviors, chronic medical conditions and medications, also contribute to bone loss.Citation122,Citation127,Citation128 HIV is an important risk factor for impaired bone health.Citation120,Citation122,Citation129–Citation134 The prevalence of low BMD among those with HIV ranges from 30% to 70%,Citation131,Citation134 while up to 15% of patients with HIV have osteoporosis.Citation135–Citation137 However, the development of bone disease in HIV is likely a multifactorial process that includes the effects of HIV infection itself, higher prevalence of other osteoporosis risk factors, as well as the impact of ART.Citation9,Citation23,Citation120,Citation122,Citation132–Citation134,Citation138–Citation142

Several studies have demonstrated that patients with HIV are more likely to experience additional osteoporosis risk factors including cigarette smoking and alcohol use, African–American or Hispanic ethnicity, decreased body mass index, vitamin D deficiency, chronic steroid use, amenorrhea, and hypogonadism.Citation9,Citation23,Citation122,Citation127,Citation128,Citation131,Citation134,Citation143–Citation154 However, there is evidence that HIV infection itself, independent of its association with these other factors, contributes to bone loss ().Citation120,Citation122,Citation129,Citation132,Citation133,Citation141,Citation142,Citation144,Citation147,Citation148,Citation155,Citation156 A meta-analysis has shown that HIV is associated with a 6.4-fold increased risk of osteopenia/low BMD and a threefold increased risk of osteoporosis.Citation129 In a cross-sectional study of 120 women over the age of 40 years, those with HIV who were postmenopausal had a lower mental index and antegonial depth on panoramic jaw X-ray examination when compared to those without HIV, while premenopausal HIV-positive women only had lower antegonial depth than HIV-negative women.Citation156 Yin et al have performed several studies demonstrating lower BMD in women with HIV (). In a cross-sectional study of HIV-positive, postmenopausal women, mean BMD in the lumbar spine and total hip were significantly lower when compared to historical matched controls.Citation144 Additionally, those with HIV were more likely to have documented osteoporosis based on T-scores at the lumbar spine (43% vs 23%) and hip (10% vs 1%) when compared to the HIV-negative controls.Citation144 In a longitudinal cohort of women in New York, adjusted analyses demonstrated that HIV-positivity was associated with lower BMD at the lumbar spine and total hip, and that women with HIV were also more likely to have higher levels of markers of bone turnover.Citation132 However, this did not translate to a higher risk of fragility fracture in this population.Citation132 In a subsequent study of HIV-positive and HIV-negative women, HIV status was not associated with an increased risk of fracture, nor was CD4 count or use of ART.Citation149 While some studies have corroborated Yin et al’s findingsCitation132,Citation149 that fracture incidence does not increase with HIV,Citation142 other studies have found evidence to the contrary.Citation146,Citation157–Citation162 In a Canadian study of 137 HIV-positive patients and 402 HIV-negative controls, those with HIV had a 1.7-fold higher lifetime risk of fragility fracture.Citation146 Similarly, association between bone loss and CD4 count among women with HIV has also been inconsistent.Citation120,Citation122,Citation129,Citation132,Citation135,Citation144,Citation145,Citation147,Citation163–Citation165

Table 4 Summary of studies assessing bone mineral density (BMD) and osteoporosis in women with HIV and menopause

Antiretroviral therapy has been associated with a decline in BMD within the first 1–2 years of therapy.Citation122,Citation129,Citation134,Citation138,Citation139,Citation166–Citation168 However, the relationship between long-term ART and bone health is not as clear, and bone loss may stabilize with ongoing therapy.Citation120,Citation128,Citation138,Citation147 In vitro studies have shown several antiretrovirals cause changes in bone metabolism; zidovudine (AZT), an NRTI,Citation169 and ritonavir, a PI,Citation140 are associated with increased osteoclast activity, while TDF causes renal phosphate wasting and predisposes to osteoporosis.Citation137,Citation167,Citation168,Citation170,Citation171 However, while TDF use has consistently been shown to cause bone loss,Citation137,Citation141,Citation167,Citation168,Citation171 clinical studies examining other antiretrovirals have not necessarily confirmed the in vitro findings.Citation141,Citation147,Citation167,Citation172 For example, in a study of 300 HIV-positive women, ART use overall was not associated with a decrease in BMD, and AZT was found to be protective against bone loss.Citation141 Another study found that NRTI use was associated with BMD decline.Citation173 Similarly, the relationship between PIs and BMD is inconsist ent,Citation120,Citation128,Citation134,Citation145,Citation155,Citation167,Citation174–Citation177 while NNRTIs and integrase inhibitors, particularly raltegravir, appear to have less of an impact on bone health.Citation122,Citation137,Citation149,Citation178,Citation179

Given that HIV is associated with changes in BMD, some experts suggest that HIV should be included in the list of medical conditions that cause secondary osteoporosis.Citation131 However, regional osteoporosis guidelines vary in their recommendations regarding screening ().Citation121,Citation131,Citation180,Citation181 Most guidelines suggest that osteoporosis risk be estimated based on a comprehensive clinical tool (such as the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool [FRAX])Citation182 to calculate a 10-year fracture risk ().Citation123,Citation131,Citation183 HIV is not included in this clinical tool. In 2015, specific guidelines were published for management of bone disease in individuals with HIV ( and ).Citation131 These guidelines suggest that all HIV-positive individuals should be assessed for their fracture risk, based on the clinical tool suggested in their appropriate regional guideline. HIV-positive individuals with one major risk factor for osteoporosis (such as men ≥50 years and postmenopausal women) should undergo screening with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry ().Citation131,Citation134 If no major risk factor exists, patients should be assessed according to age-specific recommendations: for men and premenopausal women ≥40 years of age, fracture riskshould be calculated and those at intermediate-to-high risk should undergo dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry screening.Citation131

Table 5 Guidelines for assessment of BMD in patients with HIV

Table 6 Interpretation of fracture risk assessment and DEXA scores in assessment of bone disease

Table 7 2015 Guidelines for management of bone disease in patients with HIV

With respect to management, those with HIV should be managed as per the general population, including both lifestyle modifications and pharmacologic therapy where appropriate (). Secondary causes of bone loss should be excluded. Many patients with HIV will have risk factors for vitamin D deficiency, and should be assessed for supplementation if insufficiency or deficiency exists.Citation122,Citation131,Citation184 Bisphosphonates do not have significant interactions with ART and are considered safe for use in those with HIV.Citation122 Alendronate and zoledronic acid are the preferred agents in HIV as they have been evaluated and found to be effective in this population.Citation122,Citation131,Citation185–Citation190 If bisphosphonates cannot be used, teriparatide is the suggested second-line agent, though it has not been specifically studied in patients with HIV.Citation122,Citation134 For the most part, the benefits of ART with respect to virologic control are considered to outweigh the risks of potentially exacerbating bone loss. However, in those patients who are at high risk of fracture based on a comprehensive clinical assessment, clinicians may consider avoiding TDF or PIs if reasonable alternatives are available.Citation131,Citation134

Future directions

While the body of evidence continues to grow, further research regarding the complex interaction between HIV and menopause is needed. Larger studies are required to determine if menopause affects antiretroviral pharmacokinetics and response to therapy. The influence of menopause on cervico-vaginal shedding of the HIV virus may have implications for risk of transmission and should be further evaluated. It will also be important to determine if earlier self-report of menopause is truly due to an earlier age of onset in women with HIV, or is confounded by a higher risk of amenorrhea without menopause. Therefore, future studies should consider including biochemical confirmation of menopause in order to better define this relationship. There are currently no studies specifically examining the efficacy and safety of HT in women with HIV, which likely contributes to underuse in this population. Finally, ongoing monitoring of bone health in the context of newer antiretrovirals, particularly with the introduction of tenofovir alafenamide fumarate, will be important to ensure that women are on safe and optimal anti-retroviral regimens as they transition through menopause.

Conclusion

Menopause is a pivotal life event for women, but each individual woman will have her own unique experience of the process. HIV infection is potentially associated with an increased risk of earlier menopause, more prevalent and pronounced menopausal symptoms, and likely exacerbates the changes in bone health that accompany the menopausal transition. Increasing age and menopause do not result in a cessation of sexual activity, but can affect the degree to which individuals perceive themselves to be at risk of transmitting and acquiring HIV infection, and can influence their engagement in safe sexual practices. Therefore, as patients with HIV live longer in the era of effective cART, the management of HIV infection will continue to increase in complexity. This management must occur in conjunction with the screening and management guidelines for age-related comorbidities, and must include an evaluation of the potential interactions between HIV, sexual behaviors, and other pivotal life events, including menopause.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose in this work.

References

- PalellaFJJrDelaneyKMMoormanACDeclining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study InvestigatorsN Engl J Med1998338138538609516219

- Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort CollaborationLife expectance of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studiesLancet2008372963529329918657708

- HarrisonKMSongRZhangXLife expectancy after HIV diagnosis based on national HIV surveillance data from 25 states, United StatesJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr201053112413019730109

- LimaVDHoggRSHarriganPRContinued improvement in survival among HIV-infected individuals with newer forms of highly active antiretroviral therapyAIDS200721668569217413689

- SamjiHCesconAHoggRSClosing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and CanadaPLoS One2013812e8135524367482

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)2013 Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdfAccessed November 16, 2015

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [homepage on the Internet]HIV Among Women. Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, Sexually Transmitted Diseases and Tuberculosis Prevention: US Department of Health and Human Services Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/index.html#refa. Updated June 23, 2015Accessed November 16, 2015

- Public Health Agency of CanadaHIV and AIDS in Canada: Surveillance Report to December 31, 2013Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada2014Public Health Agency of Canada2014 Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/aids-sida/publication/survreport/2013/dec/assets/pdf/hiv-aids-surveillence-eng.pdfAccessed November 16, 2015

- CejtinHECare of the Human immunodeficiency virus-infected menopausal womanAm J Obstet Gynecol20122072879322284959

- KanapathipillaiRHickeyMGilesMHuman immunodeficiency virus and menopauseMenopause201320998399023531684

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [homepage on the Internet]HIV Among People Aged 50 and Over. Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, Sexually Transmitted Diseases and Tuberculosis Prevention: US Department of Health and Human Services Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/olderamericans/index.html. Updated May 12, 2015Accessed November 16, 2015

- American Psychological Association [homepage on the Internet]KarpiakSAdherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in older adults living with HIV/AIDSAmerican Psychological Association2014 Available from: http://www.apa.org/pi/aids/resources/exchange/2014/01/anti-retroviral-therapy.aspxAccessed November 16, 2015

- FantryLEZhanMTaylorGHSillAMFlawsJAAge of menopause and menopausal symptoms in HIV-infected womenAIDS Patient Care STDS2005191170371116283830

- World Health OrganizationWHO Scientific Group on Research on the Menopause in the 1990’sWHO Technical Report Series 866Geneva, Switzerland1996 Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/41841/1/WHO_TRS_866.pdfAccessed November 16, 2015

- International Menopause Society [homepage on the Internet]Menopause Terminology. International Menopause Society Available from: http://www.imsociety.org/menopause_terminology.phpAccessed November 16, 2015

- BrambillaDJMcKinlaySMA prospective study of factors affecting age at menopauseJ Clin Epidemiol19894211103110392809660

- McKinlaySMBifanoNLMcKinlayJBSmoking and age at menopause in womenAnn Intern Med198510333503564026083

- CondeDMPinto-NetoAMCosta-PaivaLAge at menopause of HIV-infected women: a reviewGynecol Endocrinol2008242848618210331

- CalvetGAGrinsztejnBGQuintanaMSPredictors of early menopause in HIV-infected women: a prospective cohort studyAm J Obstet Gynecol20152126765.e1e1325557206

- ThomasFRenaudFBeneficeEde MeeusTGueganJFInternational variability of ages at menarche and menopause: patterns and main determinantsHum Biol200173227129011446429

- HarlowSDGassMHallJEExecutive summary of the stages of reproductive aging workshop +10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive agingMenopause201219438739522343510

- ShusterLTRhodesDJGostoutBSGrossardtBRRoccaWAPremature menopause or early menopause: long-term health consequencesMaturitas201065216116619733988

- FanMDMaslowBSSantoroNSchoenbaumEHIV and menopauseMenopause Int200814416316819037065

- BlumelJECastelo-BrancoCBinfaLQuality of life after the menopause: a population studyMaturitas2000341172310687878

- CondeDMPinto-NetoAMSantos-SaDCosta-PaivaLMartinezEZFactors associated with quality of life in a cohort of postmenopausal womenGynecol Endocrinol200622844144617012106

- UtianWHPsychosocial and socioeconomic burden of vasomotor symptoms in menopause: a comprehensive reviewHealth Qual Life Outcomes200534716083502

- Lui-FilhoJFValadaresALRGomesDCAmaralEPinto-NetoAMCosta-PaivaLMenopausal symptoms and associated factors in HIV-positive womenMaturitas201376217217823993758

- KojicEMWangCCCu-UvinSHIV and menopause: a reviewJ Womens Health (Larchmt)200716101402141118062755

- ZapantisGSantoroNThe menopausal transition: characteristics and managementBest Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab2003171335212763511

- ZablotskyDKennedyMRisk factors and HIV transmission to midlife and older women: knowledge, options, and the initiation of safer sexual practicesJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200333Suppl 2S122S13012853861

- AlthoffKNGeboKAGangeSJCD4 count at presentation for HIV care in the United States and Canada: are those over 50 years more likely to have a delayed presentation?AIDS Res Ther201074521159161

- SamuelMIWelchJTenant-FlowersMPoultonMCampbellLTaylorCCare of HIV-positive women aged 50 and over – can we do better?Int J STD AIDS201425430330524047886

- DuffusWAKettingerLStephensTMissed opportunities for earlier diagnosis of HIV infection – South Carolina, 1997–2005MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep200655471269127217136020

- DuffusWAWeisKKettingerLStephensTAlbrechtHGibsonJJRisk-based HIV testing in South Carolina health care settings failed to identify the majority of infected individualsAIDS Patient Care STDS200923533934519320598

- World Health OrganizationWHO case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunological classification of HIV-related disease in adults and childrenWHO2007 Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/HIVstaging150307.pdfAccessed November 16, 2015

- TaylorTNWeedonJGolubETLongitudinal trends in sexual behaviors with advancing age and menopause among women with and without HIV-1 infectionAIDS Behav201519593194025245474

- LindauSTSchummLPLaumannEOLevinsonWO’MuircheartaighCAWaiteLJA study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United StatesN Engl J Med2007357876277417715410

- WaiteLJLaumannEODasASchummLPSexuality: measures of partnerships, practices, attitudes, and problems in the national social life, health and aging studyJ Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci200964Suppl 1i56i6619497930

- LaumannEOGagnonJHMichaelRTThe social organization of sexuality: sexual practices in the United StatesChicagoThe University of Chicago Press1994

- DunnMECutlerNSexual issues in older adultsAIDS Patient Care STDS2000142669

- RosenRGTaylorJFGLeiblumSRBachmannGAPrevalence of sexual dysfunction in women: results of a survey study of 329 patients in an outpatient gynecological clinicJ Sex Marital Ther19941931711888246273

- BachmannGAInfluence of menopause on sexualityInt J Fertil Menopausal Stud199540Suppl 116227581585

- DiazTSchableBChuSYRelationship between use of condoms and other forms of contraception among human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. Supplement to HIV and AIDS Surveillance Project GroupObstet Gynecol19958622772827617361

- WilsonTEKoenigLJWalterEDual contraceptive method use for pregnancy and disease prevention among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women: the importance of an event-level focus for promoting safer sexual behaviorsSex Transm Dis2003301180981214603086

- SchickVHerbenickDReeceMSexual behaviors, condom use, and sexual health of Americans over 50: implications for sexual health promotion for older adultsJ Sex Med20107Suppl 531532921029388

- SchableBChuSYDiazTCharacteristics of women 50 years of age or older with heterosexually acquired AIDSAm J Public Health19968611161616188916530

- AdekeyeOAHeimanHJOnyeaborOSHyacinthHIThe new invincibles: HIV screening among older adults in the U.SPLoS One201278e4361822952722

- WigfallLTRichterDLTorresMEHIV testing among midlife women in the deep south: an analysis of the 2008 behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey dataJ Women’s Health (Larchmt)201120693394121671778

- SkiestDJKeiserPHuman immunodeficiency virus infection in patients older than 50 years. A survey of primary care physicians’ beliefs, practices and knowledgeArch Fam Med1997632892949161358

- AkersAYBernsteinLDoyleJCorbie-SmithGOlder women and HIV testing: examining the relationship between HIV testing history, age, and lifetime HIV risk behaviorsSex Transm Dis200835442042318362866

- BachmannGALeiblumSRThe impact of hormones on menopasual sexuality: a literature reviewMenopause200411112012314716193

- SenanyakePWomen and reproductive health in a graying worldInt J Gynecol Obstet20007015967

- GolubSATomassilliJCPantaloneDWBrennanMKarpiakSEParsonsJTPrevalence and correlates of sexual behavior and risk management among HIV-positive adults over 50Sex Transm Dis2010371061562021305717

- MassadLSEvansCTWilsonTEImpact of menopause on condom use by HIV-seropositive and comparison seronegative womenJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200847340140218398976

- PsarosCBarinasJRobbinsGKBedoyaCASafrenSAParkERIntimacy and sexual decision making: exploring the perspective of HIV positive women over 50AIDS Patient Care STDS2012261275576023199193

- EmletCA“You’re awfully old to have this disease”: experiences of stigma and ageism in adults 50 years and older living with HIV/AIDSGerontologist200646678179017169933

- MassadLSEvansCEWilsonTEContraceptive use among U.S. women with HIVJ Women’s Health (Larchmt)200716565766617627401

- World Health OrganizationWorld Health Organization brief on anti-retroviral treatment (ART) in HIV and TB preventionWHO2011 Available from: http://www.princeton.edu/cbli/student-projects-1/WHO-brief-on-ART-and-Community-Viral-Load-jan_2011.pdfAccessed November 16, 2015

- AttiaSEggerMMullerMZwahlenMLowNSexual transmission of HIV according to viral load and antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysisAIDS200923111397140419381076

- RollenhagenCAsinSNEnhanced HIV-1 replication in ex vivo ectocervical tissues from post-menopausal women correlates with increased inflammatory responsesMucosal Immunol20114667168121881573

- MeloKCMeloMRRicciBVSeguradoACCorrelates of human immunodeficiency virus cervicovaginal shedding among postmenopausal and fertile-aged womenMenopause201219215015621983010

- ValdiglesiasVSanchez-FloresMMasedaALymphocyte subsets in a population of nonfrail elderly individualsJ Toxicol Environ Health A20157813–1479080426167746

- BalestreEEholieSPLokossueAEffect of age on immunological response in the first year of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-infected adults in West AfricaAIDS201226895195722382142

- GrabarSKousignianISobelAImmunologic and clinical responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy over 50 years of age. Results from the French Hospital Database on HIVAIDS200418152029203815577624

- ManfrediRChiodoFA case-control study of virological and immunological effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients with advanced ageAIDS200014101475147710930176

- Van BenthemBHVernazzaPCoutinhoRAPrinsMEuropean Study on the Natural History of HIV Infection in Women and the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. The impact of pregnancy and menopause on CD4 lymphocyte counts in HIV-infected women. For the European Study on the Natural History of HIV Infection in Women and the Swiss HIV Cohort StudyAIDS200216691992411919494

- PattersonKBCohnSEUyanikJHughesMSmurzynskiMEronJJTreatment responses in antiretroviral treatment (ART) naïve pre- and post-menopausal HIV-infected women: an analysis from ACTG studiesClin Infect Dis200949347347619555288

- CalvetGAVelasqueLLuzPMAbsence of effect of menopause status at initiation of first-line antiretroviral therapy on immunologic or virologic responses: a cohort study from Rio de Janeiro, BrazilPLoS One201492e8929924586673

- DumondJBAdamsJLPrinceHMPharmacokinetics of two common antiretroviral regimens in older HIV-infected patients: a pilot studyHIV Med201314740140923433482

- GervasoniCMeravigliaPLandonioSTenofovir plasma concentrations in post-menopausal versus pre-menopausal HIV-infected womenJ Antimicrob Chemother20136851206120723299572

- CottrellMLPattersonKBPrinceHMEffect of HIV-infection and menopause status on raltegravir pharmacokinetics in the blood and genital tractAntivir Ther Epub201563

- BaxiSMGreenblattRMBacchettiPCommon clinical conditions – age, low BMI, ritonavir use, mild renal impairment – affect tenofovir pharmacokinetics in a large cohort of HIV-infected womenAIDS2014281596624275255

- OrlandoGMeravigliaPCordierLAntiretroviral treatment and age-related comorbidities in a cohort of older, HIV-infected patientsHIV Med20067854955717105515

- de PommerolMHessamferMLawson-AyayiSMenopause and HIV infection: age at onset and associated factorsInt J STD AIDS2011222677221427426

- CooperGSSandlerDPAge at natural menopause and mortalityAnn Epidemiol1998842292359590601

- JacobsenBKHeuchIKvaleGAge at natural menopause and all-cause mortality: a 37-year follow-up of 19,731 Norwegian womenAm J Epidemiol20031571092392912746245

- GradyDSawayaGFDiscontinuation of postmenopausal hormone therapyAm J Med2005118Suppl 12B16316516414343

- SoaresCNPractical strategies for diagnosing and treating depression in women: menopausal transitionJ Clin Psychiatry20086910e3019192433

- SantoroNFanMMaslowBSchoenbaumEWomen and HIV infection: the makings of a midlife crisisMaturitas200964316016419783389

- FerreiraCEPinto-NetoAMMarques CondeDCosta-PaivaLMoraisSSMagalhaesJMenopause symptoms in women infected with HIV: prevalence and associated factorsGynecol Endocrinol200723419820517505939

- SchoenbaumEEHartelDLoYHIV infection, drug use, and onset of natural menopauseClin Infect Dis200541101517152416231267

- BoonyanurakPBunupuradahTWilawanKAge at menopause and menopause-related symptoms in human immunodeficiency virus-infected Thai womenMenopause201219782082422549170

- ImaiKSuttonMYMdodoRdel RioCHIV and menopause: a systematic review of the effects of HIV infection on age at menopause and the effects of menopause on response to antiretroviral therapyObstet Gynecol Int2013201334030924454386

- ClarkRACohnSEJarekCPerimenopausal symptomatology among HIV-infected women at least 40 years of ageJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr20002319910010708064

- CejtinHEKalinowskiABacchettiPEffects of human immunodeficiency virus on protracted amenorrhea and ovarian dysfunctionObstet Gynecol200610861423143117138776

- RozenbaumHMenopause et regles en 2001. Resultats de l’enquete CLIMATSReprod Hum Hormones2002151122 French

- CejtinSHTaylorRWattsDHAssessment of menopausal status among women in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS)Proceedings of the 57th International AIDS ConferenceJuly 11–16 2004Bangkok, Thailand

- GoldEBBrombergerJCrawfordSFactors associated with age at natural menopause in a multiethnic sample of midlife womenAm J Epidemiol2001153986587411323317

- BrombergerJTMatthewsKAKullerLHWingRRMeilahnENPlatingaPProspective study of the determinants of age at menopauseAm J Epidemiol199714521241339006309

- MacMahonBWorcesterJAge at menopause. United States – 1960–1962Vital Health Stat 111966191205298639

- ClarkRAMulliganKStamenovicEFrequency of anovulation and early menopause among women enrolled in selected AIDS clinical trials group studiesJ Infect Dis2001184101325132711679923

- ShahPNSmithJRWellsCMenstrual symptoms in women infected by the human immunodeficiency virusObstet Gyencol1994833397400

- HarlowSDSchumanPCohenMEffect of HIV infection on menstrual cycle lengthJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr2000241687510877498

- MillerSASantoroNLoYMenopause symptoms in HIV-infected and drug-using womenMenopause200512334835615879925

- EnriquezMLackeyNWittJHealth concerns of mature women living with HIV in the Midwestern United StatesJ Assoc Nurses AIDS Care2008191374618191767

- TuchmanEMenopause symptom attribution among midlife women in methadone treatmentSoc Work Health Care2010491536720077319

- LoobySEShifrenJCorlessIIncreased hot flash severity and related interference in perimenopausal human immunodeficiency virus-infected womenMenopause201421440340923820600

- JohnsonTMCohenHWSantoroNAttribution of menopause symptoms in human immunodeficiency virus-infected or at-risk drug-using womenMenopause200815355155718188138

- RubinLHSundermannEECookJAInvestigation of menopausal stage and symptoms on cognition in human immunodeficiency virus-infected womenMenopause2014219997100624496085

- TuchmanEPenningtonLEKullRMDaneshyarSRelationship between menopause symptoms and HIV risk among midlife women in methadone treatment: a pilot studySubst Use Misuse201348971171823607674

- TuchmanEExploring the prevalence of menopause symptoms in midlife women in methadone maintenance treatmentSoc Work Health Care2007454436217954448

- MakiPMRubinLHCohenMDepressive symptoms are increased in the early perimenopausal stage in ethnically diverse HIV+ and HIV-womenMenopause201219111215122322872013

- MorrisonMFPetittoJMTen HaveTDepressive and anxiety disorders in women with HIV infectionAm J Psychiatry2002159578979611986133

- AtkinsonJHGrantINatural history of neuropsychiatric manifestations of HIV diseasePsychiatr Clin North Am199417117338190664

- LyketsosCGHooverDRGuccioneMChanges in depressive symptoms as AIDS develops. The multi-center AIDS cohort studyAm J Psychiatry199615311143014378890676

- MooreJSchumanPSchoenbaumEBolandBSolomonLSmithDSevere adverse life events and depressive symptoms among women, or at risk for, HIV infection in four cities in the United States of AmericaAIDS199913172459246810597788

- SorliniMLFocaEMottaDElderly women with human immunodeficiency virus infection: is there an effect of the virus on neuropsychological profile?J Am Geriatr Soc201462119419625180386

- BrombergerJTAssmannSFAvisNESchockenMKravitzHMCordalAPersistent mood symptoms in a multi-ethnic community cohort of pre- and perimenopausal womenAm J Epidemiol2003158434735612915500

- BrombergerJTMatthewsKASchottLLDepressive symptoms during the menopausal transition: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN)J Affect Disord20071031–326727217331589

- BrombergerJTKravitzHJChangYFCyranowskiJMBrownCMatthewsKAMajor depression during and after the menopausal transition: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN)Psychol Med20114191879188821306662

- MohyiDTabassiKSimonJDifferential diagnosis of hot flashesMaturitas19972732032149288692

- HartelDLoYBauerCAttitudes toward menopause in HIV-infected and at-risk womenClin Interv Aging20083356156618982926

- CookJACohenMHBurkeJEffects of depressive symptoms and mental health quality of life on use of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-seropositive womenJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200230440140912138346

- CookJAGreyDBurkeJDepressive symptoms and AIDS-related mortality among a multisite cohort of HIV-positive womenAm J Public Health20049471133114015226133

- TedaldiEMMinnitiNLFischerTHIV-associated neurocognitive disorders: the relationship of HIV infection with physical and social comorbiditiesBiomed Res Int2015201564191325815329

- Marques CondeDSilvaETAmaralWNHIV, reproductive aging, and health implications in women: a literature reviewMenopause200916119921318800017

- RichardsonJLMartinEMJimenezNNeuropsychological functioning in a cohort of HIV infected women: importance of anti-retroviral therapyJ Int Neuropsychol Soc20028678179312240742

- FreemanEWSammelMDLinHNelsonDBAssociations of hormones and menopausal status with depressed mood in women with no history of depressionArch Gen Psychiatry200663437538216585466

- LindsayRHartDMAitkenJMMacDonaldEBAndersonJBClarkeACLong-term prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis by oestrogen: evidence for increased bone mass after delayed onset of oestrogen treatmentLancet1976179681038104057448

- GomesDCValadaresALde MoraesMJLagruttaBBPinto-NetoAMCosta-PaivaLLow bone mass in human immunodeficiency virus-infected climacteric women receiving antiretroviral therapy: prevalence and associated factorsMenopause201422222423025003619

- AbergJAGallantJEGhanemKGEmmanuelPZingmanBSHorbergMInfectious Diseases Society of AmericaPrimary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with HIV: 2013 update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of AmericaClin Infect Dis201458111024343580

- HoyJBone disease in HIV: recommendations for screening and management in the older patientDrugs Aging201532754955826123948

- PapaioannouAMorinSCheungA2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summaryCMAJ2010182171864187320940232

- World Health OrganizationWHO Scientific Group on the assessment of osteoporosis as the primary care levelGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2004 Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/topics/Osteoporosis.pdfAccessed November 16, 2015

- World Health OrganizationAdherence to long-term therapies: evidence for actionGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2003 Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42682/1/9241545992.pdfAccessed November 16, 2015

- National Institutes of HealthOsteoporosis prevention, diagnosis and therapyNIH Consensus Statement200017145

- CotterAGSabinCASimelaneSRelative contribution of HIV infection, demographics and body mass index to bone mineral densityAIDS201428142051206025265073

- DolanSEKanterJRGrinspoonSLongitudinal analysis of bone density in human immunodeficiency virus-infected womenJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20069182938294516735489

- BrownTTQaqishRBAntiretroviral therapy and the prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis: a meta-analytic reviewAIDS200620172165217417086056

- Walker HarrisVBrownTTBone loss in HIV-infected patients: evidence, clinical implications, and treatment strategiesJ Infect Dis2012205Suppl 3S391S39822577213

- BrownTTHoyJBorderiMRecommendations for evaluation and management of bone disease in HIVClin Infect Dis20156081242125125609682

- YinMTMcMahonDJFerrisDCLow bone mass and high bone turnover in postmenopausal human immunodeficiency virus-infected womenJ Clin Endocrinol Metab201095262062919965927

- ArnstenJHFreemanRHowardAAFloris-MooreMSantoroNSchoenbaumEEHIV infection and bone mineral density in middle-aged womenClin Infect Dis20064271014102016511769

- McComseyGATebasPShaneEBone disease in HIV infection: a practical review and recommendations for HIV care providersClin Infect Dis201051893794620839968

- CortesYIYinMTReameNKBone density and fractures in HIV-infected postmenopausal women: a systematic reviewJ Assoc Nurses AIDS Care201526438739826066693

- BonjochAFiguerasMEstanyCHigh prevalence of and progression to low bone mineral density in HIV-infected patients: a longitudinal cohort studyAIDS201024182827283321045635

- McComseyGAKitchDDaarESBone mineral density and fractures in antiretroviral-naïve persons randomized to receive abacavir-lamivudine or tenofovir-disoproxil-fumarate-emtricitabine along with efavirenz or atazanvir-ritonavir: AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5224s, a substudy of ACTG A5202J Infect Dis2011203121791180121606537

- BollandMJWangTKGreyAGambleGDReidIRStable bone density in HAART-treated individuals with HIV: a meta-analysisJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20119692721273121715534

- BrownTTMcComseyGAKingMSQaqishRBBernsteinBMda SilvaBALoss of bone mineral density after antiretroviral therapy initiation, independent of antiretroviral regimenJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr200951555456119512937

- YinMTModarresiRShaneEEffects of HIV infection and anti-retroviral therapy with ritonavir on induction of osteoclast-like cells in postmenopausal womenOsteoporos Int20112251459146820683705

- Pinto-NetoLFRagi-EisSVieiraNFLow bone mass prevalence, therapy type, and clinical risk factors in an HIV-infected Brazilian populationJ Clin Densitom201114443443922051092

- ArnstenJHFreemanRHowardAAFloris-MooreMLoYKleinRSDecreased bone mineral density in aging men with or at risk for HIV infectionAIDS200721561762317314524

- SteinEMYinMTMcMahonDJVitamin D deficiency in HIV-infected postmenopausal Hispanic and African-American womenOsteporos Int2011222477487

- YinMTDobkinJBrudneyKBone mass and mineral metabolism in HIV+ postmenopausal womenOsteoporos Int200516111345135215754081

- SharmaACohenHWFreemanRSantoroNSchoenbaumEEProspective evaluation of bone mineral density among middle-aged HIV-infected and unifected women: association between methadone use and bone lossMaturitas201170329530121944566

- PriorJBurdgeDMaanEFragility fractures and bone mineral density in HIV-positive women: a case-control population-based studyOsteporos Int2007181013451353

- DravidAKulkarniMBorkarADhandeSPrevalence of low bone mineral density among HIV patients on long-term suppressive antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited setting of western IndiaJ Int AIDS Soc2014174 Suppl 31956725394074

- SharmaAFlomPLRosenCJSchoenbaumEERacial differences in bone loss and relation to menopause among HIV-infected and uninfected womenBone201577243025896953

- YinMTShiQHooverDRFracture incidence in HIV-infected women: results from the Women’s Interagency HIV StudyAIDS201024172679268620859192

- RodriguezMDanielsBGunawardeneSRobbinsGKHigh frequency of vitamin D deficiency in ambulatory HIV-positive patientsAIDS Res Hum Retroviruses200925191419108690

- DobsASDempseyMALadensonPWPolkBFEndocrine disorders in men infected with human immunodeficiency virusAm J Med1988843 Pt 26116163348269

- HaugCJAukrustPHaugEMorkridLMullerFFrolandSSSevere deficiency of 1,25-dihdyroxyvitamin D3 in human immunodeficiency virus infection: association with immunological hyperactivity and only minor changes in calcium homeostasisJ Clin Endocrinol Metab19988311383238389814454

- HuangJSWilkieSJSullivanMPGrinspoonSReduced bone density in androgen-deficient women with acquired immune deficiency syndrome wastingJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20018683533353911502775

- BollandMJGreyABGambleGDReidIRLow body weight mediates the relationship between HIV infection and low bone mineral density: a meta-analysisJ Clin Endocrinol Metab200792124522452817925333

- AnastosKLuDShiOThe association of bone mineral density with HIV infection and antiretroviral treatment in womenAntivir Ther20071271049105818018763

- CaputoBVTraversa-CaputoGCCostaCGiovaniEMEvaluation of bone alterations in the jaws of HIV-infected menopausal womenBraz Oral Res201327323123723657485

- YinMTShuAZhangCATrabecular and cortical microarchitecture in postmenopausal HIV-infected womenCalcif Tissue Int201392655756523460340

- ShiauSBrounECArpadiSMYinMTIncident fractures in HIV-infected individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysisAIDS201327121949195724126140

- WomackJAGouletJLGibertCIncreased risk of fragility fractures among HIV infected compared to uninfected male veteransPLoS One201162e1721721359191

- TriantVABrownTTLeeHGrinspoonSKFracture prevalence among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected versus non-HIV-infected patients in a large U.S. healthcare systemJ Clin Endocrinol Metab20089393499350418593764

- DaoCYoungBBuchaczKHigher and increasing rates of fracture among HIV-infected persons in the HIV-Outpatient Study (HOPS) compared to the general US population, 1994 to 2008 [abstract 128]Program and abstracts of the 17th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic InfectionsFebruary 18, 2010San Francisco, California

- CollinFDuvalXLe MoingVTen-year incidence and risk factors of bone fractures in a cohort of treated HIV-1 infected adultsAIDS20092381021102419300202

- Guerri-FernandezRVestergaardPCarbonellCHIV infection is strongly associated with hip fracture risk, independent of age, gender, and comorbidities: a population-based cohort studyJ Bone Miner Res20132861259126323362011

- GrantPMKitchDMcComseyGALow baseline CD4+ count is associated with greater bone mineral density loss after antiretroviral therapy initiationClin Infect Dis201357101483148823943825

- CarrAGrundBNeuhausJPrevalence of and risk factors for low bone mineral density in untreated HIV infection: a substudy of the INSIGHT Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment (START) trialHIV Med201516Suppl 113714625711332

- CassettiIMadrugaJVSuleimanJMThe safety and efficacy of tenofovir DF in combination with lamivudine and efavirenz through 6 years in antiretroviral-naïve HIV-1 infected patientsHIV Clin Trials20078316417217621463

- DuvivierCKoltaSAssoumouLGreater decrease in bone mineral density with protease inhibitor regimens compared with non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor regimens in HIV-1-infected naïve patientsAIDS200923781782419363330

- GallantJEStaszewskiSPozniakALEfficacy and safety of tenofovir DF vs. stavudine in combination therapy in antiretroviral-naïve patients: a 3 year randomized trialJAMA2004292219120115249568

- PanGWuXMcKennaMAFengXNagyTRMcDonaldJMAZT enhances osteoclastogenesis and bone lossAIDS Res Hum Retroviruses200420660862015242537

- FuxCARauchASimcockMTenofovir use is associated with an increase in serum alkaline phosphatase in the Swiss HIV Cohort StudyAntivir Ther20081381077108219195333

- StellbrinkHJOrkinCArribasJRComparison of changes in bone density and turnover with abacavir-lamivudine versus tenofovir-emtricitabine in HIV-infected adults: 48-week results from the ASSERT studyClin Infect Dis201051896397220828304

- MallonPWHIV and bone mineral densityCurr Opin Infect Dis20102311820010102

- TsekesGChrysosGDouskasGBody composition changes in protease inhibitor-naïve HIV-infected patients treated with two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitorsHIV Med200232859012010354

- TebasPPowderlyWBClaxtonSAccelerated bone mineral loss in HIV-infected patients receiving potent antiretroviral therapyAIDS2000144F63F6710770534

- Fernandez-RiveraJGarciaRLozanoFRelationship between low bone mineral density and highly active antiretroviral therapy including protease inhibitors in HIV-infected patientsHIV Clin Trials20034533734614583850

- MondyKYarasheskiKPowderlyWGLongitudinal evolution of bone mineral density and bone markers in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individualsClin Infect Dis200336448249012567307

- JonesSRestrepoDKasowitzARisk factors for decreased bone density and effects of HIV on bone in the elderlyOsteporos Int2008197913918

- BlochMTongWWHoyJSwitch from tenofovir to raltegravir increases low bone mineral density and decreases markers of bone turnover 48 weeksHIV Med201415637338024460797

- CotterAGMallonPWThe effects of untreated and treated HIV infection on bone diseaseCurr Opin HIV AIDS201491172624263798

- AsboeDAitkenCBoffitoBritish HIV Association guidelines for the routine investigation and monitoring of adult HIV-1-infected individuals, 2011HIV Med201213114422171742

- European AIDS Clinical SocietyEACS Guidelines Version 7.1EACS2014 Available from: http://www.eacsociety.org/files/guidelines-7.1-english.pdfAccessed November 16, 2015

- World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases, University of Sheffield, UKFRAX – WHO Fracture Risk Assessment Tool Available from: https://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jspAccessed November 16, 2015

- WattsNBBilezikianJPCamachoPMAmerican Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosisEndocrine Practice201016Suppl 313621224201

- AllavenaCDelpierreCCuzinLHigh frequency of vitamin D deficiency in HIV-infected patients: effects of HIV-related factors and antiretroviral drugsJ Antimicrob Chemother20126792222223022589455