Abstract

Mother and baby units (MBUs) provide inpatient psychiatric care for mothers and their infants up to a year after childbirth. They are commissioned to support the mother–infant relationship as well as stabilize maternal mental health. As their efficacy at meeting these aims had not previously been systematically assessed, this paper reviewed the international literature relating to psychological outcomes following MBU admission. A systematic search of five databases identified 23 papers eligible for inclusion, reporting on a range of outcomes indicating positive effects on maternal mental health and the mother–infant relationship and an absence of adverse effects on child development. The review also highlighted specific groups responding less favorably to MBU admission, eg, mothers with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Although the included studies were of variable methodological quality, the research findings consistently indicated positive effects. Implications for research and clinical practice are outlined in the discussion.

Introduction

Recent figures indicate approximately 20% of women experience postpartum mental health difficulties,Citation1 and four in every 1,000 women require inpatient admission postnatally.Citation2 Specialist mother and baby units (MBUs) provide joint admissions of mothers and babies for inpatient treatment and monitoring of the mother–infant relationship. MBU provision varies internationally. Currently, there are MBUs in the UK (n=17), France, Belgium, Germany, and Australia.Citation1 The US and India have MBUs, but they are fewer in number.Citation3 Some units are mother–baby facilities (MBFs), which are general psychiatric units with capacity for joint admissions, not dedicated MBUs. “MBU” is used to refer to both MBUs and MBFs throughout this review.

MainCitation4 observed that separating the mother and infant during the 1st year could impact negatively on the developing attachment relationship. Joint admission, hypothesized to be beneficial for both parties, allows for the observation of the mother caring for her infant and for a thorough risk assessment. Consequently, MBUs have been recommended in clinical guidelines internationally. The National Institute for Health and Care ExcellenceCitation5 outlined the role of MBUs in managing mental health problems during pregnancy, assessing mental illness, risks, and parenting skills, and providing expert care for the mother and infant. Similarly, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines NetworkCitation6 recommended mothers have the option of joint MBU admission. However, over the 50 years since Main’sCitation4 initial observations, little has been published regarding the effect of MBU treatment. To date, no reviews have evaluated its psychological outcomes, despite the important clinical treatment these units provide for mothers in crisis.

Aims

The aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the psychological outcomes of MBU admission: 1) by addressing how admission impacted on maternal mental health, mother–infant relationships, and child health and development, and 2) by evaluating the methodological robustness of the research. Further aims included identifying the commonly used outcome measures and exploring the efficacy of particular MBU treatments.

Literature search

Strategy and findings

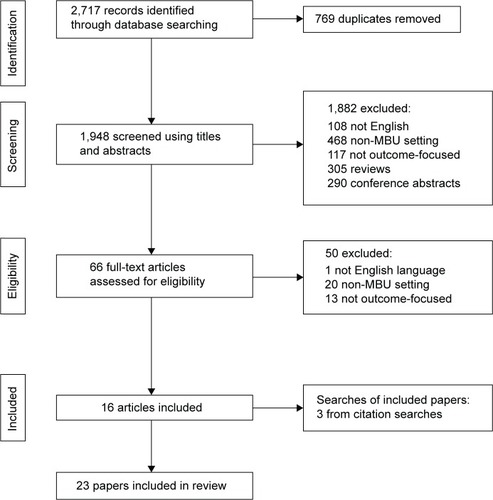

A systematic search used Ovid to review five databases from inception to January 2, 2015: PsycInfo, Medline, Embase, Health Management Information Consortium, and Maternity and Infant Care. Furthermore, reference lists of included papers were hand-searched for relevant articles, and citation searches were completed on included papers.

Search terms included “mother and baby unit$” OR “mother-baby unit$” OR “postnatal mental health$” OR “mother-baby psychiat$” OR “mother-infant unit$” OR “postpartum depressi$” OR “postpartum psychos$” OR “perinatal psychia$” OR “postnatal psychia$” OR “postpartum psychia$” AND “outcome$” OR “maternal clinical outcome$” OR “parenting outcome$” OR “attachment$” OR “bond$” OR “mother-infant interaction$”. , based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-AnalysesCitation7 guidelines, outlines the search process.

Figure 1 Flowchart demonstrating literature-review procedure.

The Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs (QATSDD) was chosen because the methodologies used in these studies were expected to be diverse.Citation8 Each of the 14 QATSDD items related to quantitative studies was rated on a 4-point scale from “not at all” (0) to “complete” (3). Consistent with other uses of this measure, percentage scores were reported, calculated using the actual score and the maximum total score of 42. Papers scoring over 75% were considered “high” quality, those between 50% and 75% “good”, 25%–50% “moderate”, and below 25% “poor”. The first author and a peer, independent to the study team, independently rated all papers and resolved any discrepancies through discussion. Interrater reliability was very good (κ =0.91). The relevant information is summarized in and .

Table 1 Settings of studies included in review and reported demographic characteristics (in chronological order)

Table 2 Designs and outcomes of included studies

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were: 1) English language, 2) published in a peer-reviewed journal, 3) reporting outcomes relating to women admitted to a psychiatric MBU, 4) assessing maternal well-being, the mother–infant relationship, child development, or another psychological outcome, and 5) including assessment of change over time or functioning at discharge. Reviews were excluded. Studies on child-care arrangementsCitation9 and relapse ratesCitation10 were also excluded, as were studies in “mothercraft” units.Citation11

Search results

Selection of studies

A total of 23 papers were identified for inclusion in this review.

MBU/MBF characteristics

The units ranged from four to 13 beds, and had multidisciplinary staff teams (). As information about treatments offered was sparse, collating comparable findings was difficult. Only eight papers described psychological treatments that focused on the mother or the mother–infant relationship.

Characteristics of participants

This review is based on 5,023 participants, including 215 control participants (4.3%). Primary diagnoses included depressive disorders (50% of the sample), schizophrenia (25%), and bipolar disorder (10%). The remaining 15% had diagnoses of anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and intellectual disabilities. The studies varied in their participant descriptions; most included maternal and child age and marital status; few provided further details ().

Characteristics of studies

Of the 23 papers, nine assessed mother–infant and maternal clinical outcomes, eight mother–infant outcomes, and six maternal clinical outcomes (). Five included a follow-up period, ranging from 1 to 6 years. Most used cohort designs, without control or comparison groups, although one presented a case series of two mothers.Citation12 Five studies used a controlled design; four compared mothers admitted to an MBU with various groups, including healthy and depressed mothers in the community. One study compared different treatment programs.Citation13

Quality ratings

QATSDD scores ranged from 29% to 83%, with a mean of 62% (). Baker et alCitation14 obtained the lowest rating, due to a lack of clarity of aims, justification of methodology, and description of procedure. In total, five papers scored as moderate quality, 12 as good, and six as high (). No relationship was observed between quality and design or year of publication. As this is the first review of MBU-related psychological outcomes, all studies were retained to present a comprehensive picture of the available research.

Study findings

Findings were grouped by outcome and methodology (see for a summary).

Maternal mental health outcomes

Fifteen studies assessed maternal outcomes. Four used the Marcé checklist, an international scale using categories of “symptom-free”, “considerably improved”, “slightly improved”, and “no change or decline”. Ten used standardized tools, such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)-II,Citation15 but oneCitation16 was unclear about the method, appearing to use clinical judgment.

The Marcé checklist

The Marcé checklist is an international checklist to be completed with all joint admissions, with 53 items regarding diagnosis, the presence or absence of specific symptoms, treatment and outcome, and information on obstetric history and ethnicity. Two papersCitation17,Citation18 detailed Marcé audits in the UK, covering 1996–2002 and 1994–2000, respectively. A further two reported audits of French MBUs over 2001–2007Citation19 and 1999–2000.Citation20 To compare data categories, “symptom-free” and “considerably improved” were combined, as were the “no change” and “worse” categories. The results were comparable across audits, with around 70% “symptom-free or considerably improved”. Similar research assessed women admitted from 1959 to 1965; 44.6% were symptom-free at discharge, although 14.8% had poor adjustment at follow-up.Citation16 Unfortunately, a mixture of methods were used to assess follow-up outcomes, making assessments imprecise, with small samples prohibiting valid conclusions.Citation16 Furthermore, given the timeframe of this study, it is questionable how comparable these figures are to more recent research.

Maternal education, occupation, employment status, relationship status, and substance use during pregnancy were identified as predicting being “symptom-free or considerably improved”.Citation19 Women with personality disorders or nonaffective psychotic disorders improved less than women with mood or acute transient psychotic disorders.Citation18,Citation20

Standardized psychometrics

Several studies used psychometric self-report tools to measure change during follow-up periods. OneCitation21 showed significant decreases in depression (BDI-II),Citation15 state and trait anxiety (State Trait Anxiety Inventory)Citation22 and state anger (State Trait Anger Expression Inventory).Citation23 Furthermore, participants reported less negative and more positive affect (Leuven Emotions Scale).Citation24 Therefore, the majority had good mental health at follow-up, although 39% were clinically depressed. Further analysisCitation25 noted participants remained depressed if they were more severely depressed and more self-critical (Depressive Experiences Questionnaire)Citation26 at admission. Another studyCitation27 assessed depression (BDI)Citation28 over a 4- to 6-year-follow-up period, with comparable findings: 21% of participants were clinically depressed at follow-up, and 60% reported current mental health needs.

In research reporting slightly better outcomes,Citation29 16% of MBU participants reported some depressive symptoms at 12 months postpartum, although none met diagnostic criteria (BDI).Citation28 In contrast, 44% of a community ill group reported symptoms and 19% met diagnostic criteria. This may indicate the superiority of inpatient treatment or reflect intergroup differences. The community ill group had diagnoses of depression, whereas the MBU group had other diagnoses, including schizophrenia. Therefore, outcome differences could be due to variations in the chronicity or treatability of each disorder. Additionally, follow-up was conducted at 12 months postpartum rather than a specified time since MBU discharge. Therefore, it is questionable whether this could be viewed as MBU outcome data.

These results are consistent with research using psychometric tools to assess change over admission. One studyCitation30 found depression and anxiety significantly reduced (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale [EPDS], Patient Health Questionnaire 9, Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale 7),Citation31–Citation33 and participants reported an increase in overall functioning (Work and Social Adjustment Scale).Citation34 Similar researchCitation35 with participants with schizophrenia recorded significant improvements in psychotic symptoms (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, PANSS).Citation36 Focusing on postpartum psychosis, a further studyCitation37 showed 92.2% of participants were symptom-free at discharge (EPDS, Clinical Global Impression scale [CGI], Young Mania Rating Scale),Citation31,Citation38,Citation39 although those with depressive features had a longer recovery period than those with manic features.

One studyCitation13 used the EPDSCitation31 to assess video-feedback interventions during admission, comparing this to verbal feedback and standard care. EPDS scores significantly improved across groups, and no intervention was significantly superior to any other.

Two studies reported changes in illness severity over admission, although neither statistically assessed these for significance. Firstly, a decrease in CGICitation38 scores was noted for those with both postpartum depression and postpartum psychosis.Citation40 Secondly, lower Wittenborn Psychiatric Rating ScaleCitation41 scores were found for participants admitted with their child than those without.Citation14 Without statistical assessment, it is hard to draw conclusions from these differences.

Therefore various psychometric tools have demonstrated improvements in maternal mental health symptoms over admission and into follow-up periods, with slower recovery for those with depressive featuresCitation37 and self-criticism.Citation25 While some superiority has been demonstrated to community-based treatment, the research also shows symptoms persisting at follow-up.

Summary of maternal mental health outcomes

Numerous data-collection methods, follow-up periods, and inclusion criteria were used, yet the results indicate improvement in maternal mental state from admission to discharge or to follow-up. These findings are promising, as are the results of the studies using control groups. However, the methodological concerns, including design issues, such as small sample sizes and diagnostic group differences, limit the implications of these results. Diagnostically, it appears that psychotic disorders, personality disorders, and high levels of self-criticism are related to poorer outcomes, but there is not enough research to draw firm conclusions.

Mother–infant outcomes

Seventeen papers assessed child or mother–infant outcomes (), using the Marcé checklist (n=4) or other standardized tools (n=13).

Rating scales of the mother–infant relationship

Several studies used scales to assess the mother–infant relationship, including either self-report or staff-rated scales. The Emotional Availability – Self-Report scale identified significant increases in the child’s capacity to involve their parent and the affect quality of the interaction over a 3.5-year follow-up period.Citation21 Participants who were depressed at follow-up had significantly lower levels of mutual attunement than nondepressed participants.

Similar progress was recorded over admission with both a staff-completed scale (Bethlem Mother–Infant Interaction Scale [BMIS])Citation42 and self-report scale (Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire).Citation40,Citation43 At admission, participants with postpartum depression rated their bonding as more problematic than participants with postpartum psychosis. In contrast, staff ratings recorded more difficulties for participants with postpartum psychosis. At discharge, all self-report scores were below clinical thresholds and staff ratings were reduced. A further study also showed BMIS scores improved significantly over MBU admission, and differed by diagnosis; scores at discharge were better for those with unipolar depression or bipolar disorder than those with schizophrenia.Citation44 In a sample of mothers with schizophrenia,Citation35 scores increased on most BMIS subscales over admission. The Infant/Caregiver Behavior Scale recorded significant improvements on dyadic and maternal responses, but only on three of eight infant-response scales.Citation35 However, validity or reliability Infant/Caregiver Behavior Scale data were unavailable, so these findings must be viewed cautiously.

In a comparison of three groups of participants receiving video feedback, verbal feedback, or standard care, improved parenting confidence (Parenting Sense of Competence Scale)Citation45 was noted for the verbal feedback and standard-care groups, but perceptions of infant behavior remained unchanged for all three groups (Neonatal Perception Index).Citation13,Citation46 Although data were not presented, the authorsCitation13 reported no superiority of either intervention over standard care, nor any significant difference between the interventions.

In summary, rating scales indicated improvements in the mother–infant relationship through admission and into follow-up. They suggested that mothers with depression perceive more difficulties in their relationship than are recorded by nursing staff. There is some indication that participants with schizophrenia have more difficulties in the mother–infant relationship at discharge than those with other diagnoses. Improvements in the relationship were not shown to differ according to the offered intervention.

Observational measures of the mother–infant relationship

A range of observational measures was used to assess the mother–infant relationship at either discharge or follow-up. At 12 months postpartum, 58% of children of MBU-admitted participants were securely attached, as were 38% of children of community participants, neither differing significantly from their matched controls.Citation29 This is markedly similar to rates of secure attachment at 4–6 years after discharge from an MBU.Citation27 Higher rates of insecure attachments were noted for MBU participants with affective disorders compared to those with bipolar disorders,Citation29 consistent with the literature on the different psychopathologies.Citation47 The depressed MBU participants engaged in significantly less affectionate talk with their children than the depressed community group (Play Observation Scheme and Emotion Rating).Citation29,Citation48

In contrast, when compared with community-ill participants, the CARE-IndexCitation49 showed MBU participants had significantly better mother–infant relationships.Citation50 However, all community ill participants had comorbid personality disorders, compared with only one MBU participant. Previous research related personality disorders to poorer treatment outcomes,Citation19 suggesting improvements in the MBU participants could be due to diagnostic differences. This could also explain the contradiction with the previous research,Citation29 which was limited to participants with depression.Citation29 Furthermore, postpartum assessment times varied greatlyCitation50 (8.9 weeks for the community ill group, 22.3 weeks for the healthy group, and 20.6 weeks for the MBU group), meaning the community-ill group had less time to adjust to motherhood.

Two studiesCitation51,Citation59 used the Global Rating Scales of Mother–Infant InteractionCitation52 to assess participants at MBU discharge. Again, results differed by diagnosis: participants with schizophrenia had the lowest interaction scores, being significantly less accepting and warm than participants with affective disorders. Ratings of video interactions of MBU participants and healthy mothers were used to focus on mind-mindedness or the caregivers’ ability to understand their child’s internal state.Citation53,Citation54 MBU participants with schizophrenia talked to their infants significantly more, and infants of participants with mania looked at their mothers more at discharge than admission. However, the research failed to reveal the hypothesized intergroup difficulties in mind-mindedness; the authors related this finding to the assessment schedule, which was designed for healthy mothers and did not appear to capture observed instances of nonattunement.

Outcomes from video feedback were reported in a case series of two symptom-free participants with schizophrenia admitted to the same MBU in India,Citation12 and both showed improvements on the Pediatric Infant Parent Exam;Citation55 however, the sample was too small to draw meaningful conclusions.

Therefore, the observational measures recorded similar findings to the rating scales, revealing improvements in mother–infant interactions over admission and into follow-up. Regarding diagnosis, the research is mixed. More difficulties appeared to be experienced at discharge by participants with schizophrenia or personality disorders, although attachment styles at follow-up were less positive for participants with affective disorders.

Parenting skills

Three studies used the Marcé checklist to report on parenting skills.Citation17,Citation20,Citation56 The French auditCitation20 recorded more parenting difficulties than either UK audit.Citation17,Citation56 When viewed by diagnosis, outcomes were significantly worse for those with schizophrenia; however, schizophrenia rates in the French auditCitation20 were nearly double those in either UK audit,Citation17,Citation56 potentially explaining this discrepancy.

The Mothering Skills Rating Scale was used to assess aspects of parenting skills, including practical management, daily routine, and interactional tasks, which were rated “incompetent”, “passable” or “competent”.Citation57 Data were missing for 14 of the 36 participants, and no analysis contrasting those with complete data and those with missing data was reported. Potentially, staff made more effort to complete ratings for specific mothers, introducing bias. A trend for improvement in parenting competence over admission was observed, as “incompetent” ratings decreased and “passable” ratings increased. Unfortunately, it is difficult to differentiate this from the natural increase in parenting skills that might be expected for all mothers.

Child development

Only two studies considered the development of children whose mothers were admitted to an MBU. OneCitation20 included the Marcé checklist data of child’s health at discharge: 76% of children were rated as having good health or no problems, and recorded difficulties were often transitory. A further studyCitation27 used a range of standardized tools with children whose mothers had been discharged 4–6 years previously. No concerns with behavioral, emotional, or cognitive functioning were revealed. However, only 28% of eligible mothers participated, limiting the power of this study.

Summary of mother–infant outcomes

The quality of mother–infant interactions generally improved, regardless of assessment method. Although mothers with schizophrenia had the poorest outcomes, attachment studies suggest higher levels of insecure attachment in children of mothers with affective disorders.

Discussion

This review systematically examined 23 identified studies reporting on outcomes following MBU admission. In summary, the research indicated improvements in maternal mental health, mother–infant relationship, and child development. However, studies also indicated poorer outcomes for specific groups of mothers, particularly those with a personality or psychotic disorder, severe depression, or high self-criticism. Furthermore, outcomes were influenced by variables indicating socioeconomic status, including education and employment. However, without further research, it remains possible that the diagnostic differences were related to the higher rates of stigma attached to specific diagnoses.Citation58

The second aim of this review concerned the methodologies used: given the urgent care MBUs provide, it was not surprising that no randomized control trials were identified. Although only four studies included a control group, these were not always optimal, eg, differing substantially from the MBU participants in diagnosis. Therefore, sample sizes, outcome measures, and designs varied greatly, making it difficult to draw overarching conclusions, yet reflecting the reality of clinical services. Most studies appropriately assessed participants at admission and discharge only, but without follow-ups to assess lasting change.

With regard to the measures commonly used, there was little consistency across the studies. Maternal mental health was assessed using self-report or staff-rating scales, mostly the BDI (n=4) for symptom change and the Marcé checklist (n=4) for improvement indicators. Specific symptoms or difficulties, such as psychosis, were assessed with specific measures, such as the PANSS. The mother–infant relationship was assessed using staff rating, video-observation rating, and self-report scales. Child development was assessed using self-report, observational measures, and the Marcé checklist. Overall, no single outcome measure or methodology dominated across the 23 studies.

This review also aimed to report on the efficacy of MBU-based interventions; however, no intervention appeared to be consistently offered, nor was any superior when compared with other interventions. For example, video feedback was used, but was not found to be superior to verbal feedback or standard care.Citation13 An important observation was that most studies provided limited descriptions of the staffing, theoretical underpinnings, and psychosocial interventions provided in each unit. Therefore, it was not possible to explore relationships between these interventions and outcomes.

Limitations

A major limitation is the variable quality of the available studies. While randomized controlled trials were not expected, even the studies with control groups had weaknesses, limiting the strength of the conclusions that can be drawn. Furthermore, descriptions of each MBU and their participants were sparse. Although the use of the QATSDD quality measure allowed for the diverse designs used in these 23 papers to be compared, there were methodological weaknesses that it did not capture, including the suitability of control-group participants and differing assessment time points. Additionally, scores were categorized by the authors into groups to assist with interpretation, so must be viewed with some caution. However, rather than using opportunistic control groups, researchers should seek more appropriate comparators and include follow-ups, as patients may access additional services after MBU discharge.

Recommendations for future research

This review highlighted the limited quality of existing research. Future studies should at the very least include detailed descriptions of the studied unit, including size, staffing, and intervention approaches, allowing units to be contrasted and outcomes compared. Socioeconomic details should also be reported, given their possible association with outcome. Greater use of control groups would provide a comparative base for identified outcomes; ideally, these would be matched in terms of child age and socioeconomic or educational background. However, outside the research context, the use of control groups as comparators may not be practicable, which is why greater priority should be given to the systematic reporting of routinely collected admission and discharge data. Currently, the range of measures being used makes it difficult to compare outcomes reported by MBUs. Although the Marcé checklist was used in some studies, it is not a validated assessment tool sensitive to change. The BMIS was used to assess the mother–infant relationship in three studies. However, many observational measures (including the CARE-Index) can only be used if staff are trained in their use, are reliable raters, and receive regular supervision to ensure interrater reliability remains high, which can be costly undertakings for services. Similarly, assessing maternal mental health can be complex; measures may be more or less relevant depending on the diagnostic group. At the very least, these outcomes should be assessed at admission and discharge, and where possible with an appropriate follow-up.

Recommendations for clinical practice

In clinical practice, measures need to be quick, easy, and require minimal training. For maternal mental health, staff-rated CGICitation38 scales of illness severity, improvement, and intervention effect may be appropriate, and could be completed during ward round. Quality will depend on the expertise and experience of staff completing the rating; however, this very quick measure is freely available, requires no training, and is transdiagnostic. Additionally, the BMIS, developed in MBUs for nurses to rate the mother–infant relationship, is freely available and requires no training. At admission, some patients may lack the capacity to complete measures; therefore, staff-rated measures may be more appropriate. However, it could be informative to collect self-report measures when possible, given the differences revealed by research comparing these methods.Citation40 If similar measures are used, this would allow for comparisons with other MBUs and their clinical service contexts. Furthermore, the data relating to specific diagnostic groups and socioeconomic characteristics suggest staff may be able to identify mothers requiring more support, allowing for the planning of longer admissions or longer outpatient follow-up.

Conclusion

Joint admissions were recommended by MainCitation4 in 1958, and specialist MBUs followed shortly thereafter. Despite this history, this is the first review to collate systematically all studies reporting on outcomes following MBU admission. While the evidence base is neither large nor methodologically robust, this review finds encouraging evidence that MBUs positively impact on maternal mental health, the mother–infant relationship, and possibly child development. However, due to the limitations of these studies, these conclusions are preliminary. The recommendations aim to support the growth of this emerging research literature to guide clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Nadine Santos for her assistance as an independent rater.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BauerAParsonageMKnappMIemmiVAdelajaBThe Costs of Perinatal Mental Health ProblemsLondonCentre for Mental Health and London School of Economics2014

- NHSEnglandNHS Standard Contract for Specialised Perinatal Mental Health ServicesLeedsNHS England2013

- Glangeaud-FreudenthalNMHowardLMSutter-DallayALTreatment – mother-infant inpatient unitsBest Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol201428114715724054169

- MainTFMothers with children in a psychiatric hospitalLancet19582705184584713589026

- National Institute for Health and Care ExcellenceAntenatal and Postnatal Mental Health: Clinical Management and Service GuidanceManchesterNICE2014

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines NetworkManagement of Perinatal Mood Disorders: A National Clinical GuidelineEdinburghSIGN2012

- MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJAltmanDGPreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statementAnn Intern Med2009151426426919622511

- SirriyehRLawtonRGardnerPArmitageGReviewing studies with diverse designs: the development and evaluation of a new toolJ Eval Clin Pract201218474675221410846

- HowardLMThornicroftGSalmonMApplebyLPredictors of parenting outcome in women with psychotic disorders discharged from mother and baby unitsActa Psychiatr Scand2004110534735515458558

- GarfieldPKentAPaykelESCreightonFJJacobsonRROutcome of postpartum disorders: a 10 year follow-up of hospital admissionsActa Psychiatr Scand2004109643443915117288

- FisherJFeekeryCRoweHTreatment of maternal mood disorder and infant behaviour disturbance in an Australian private mothercraft unit: a follow-up studyArch Womens Ment Health200471899314963738

- ReddyPDDesaiGHamzaAKarthikSAnanthanpillaiSTChandraPSEnhancing mother infant interactions through video feedback enabled interventions in women with schizophrenia: a single subject research design studyIndian J Psychol Med201436437337725336768

- BilsztaJLBuistAEWangFZulkefliNRUse of video feedback intervention in an inpatient perinatal psychiatric setting to improve maternal parentingArch Womens Ment Health201215424925722588508

- BakerAAMorisonMGameJAThorpeJGAdmitting schizophrenic mothers with their babiesLancet19612719623723913686066

- BeckATSteerRABrownGKBeck Depression Inventory. Manual – Swedish versionSandviken, SwedenPsykologiförlaget2005

- BardonDGlaserYIProtheroDWestonDHMother and baby unit: psychiatric survey of 115 casesBr Med J1968256077557585656282

- SalmonMPAbelKWebbRWarburtonALApplebyLA national audit of joint mother and baby admissions to UK psychiatric hospitals: an overview of findingsArch Womens Ment Health200471657014963735

- SalmonMAbelKCordingleyLFriedmanTApplebyLClinical and parenting skills outcomes following joint mother-baby psychiatric admissionAust N Z J Psychiatry200337555656214511083

- Glangeaud-FreudenthalNMSutterALThieulinACInpatient mother-and-child postpartum psychiatric care: factors associated with improvement in maternal mental healthEur Psychiatry201126421522320542413

- Glangeaud-FreudenthalNMMother-baby psychiatric units (MBUs): national data collection in France and in Belgium (1999–2000)Arch Womens Ment Health200471596414963734

- VliegenNCasalinSLuytenPHospitalization-based treatment for postpartum depressed mothers and their babies: rationale, principles, and preliminary follow-up dataPsychiatry201376215016823631545

- SpielbergerCDGorsuchRLLusheneREManual for the State-Trait Anxiety InventoryPalo Alto (CA)Consulting Psychologists1970

- SpielbergerCDState-Trait Anger Expression Inventory: Professional ManualOdessa (FL)Psychological Assessment Resources1996

- FontaineJRJPoortingaYHSetiadiBMarkamSSCognitive structure of emotion terms in Indonesia and the NetherlandsCogn Emot20021616186

- VliegenNLuytenPBesserACasalinSKempkeSTangEStability and change in levels of depression and personality: a follow-up study of postpartum depressed mothers that were hospitalized in a mother-infant unitJ Nerv Ment Dis20101981455120061869

- BlattSJD’AfflittiJPQuinlanDMExperiences of depression in normal young adultsJ Abnorm Psychol1976854383389956505

- WanMWWarburtonALApplebyLAbelKMMother and baby unit admissions: feasibility study examining child outcomes 4–6 years onAust N Z J Psychiatry200741215015617464693

- BeckATWardCHMendelsonMMockJErbaughJKAn inventory for measuring depressionArch Gen Psychiatry19614656157113688369

- HipwellAEGoossensFAMelhuishECKumarRSevere maternal psychopathology and infant-mother attachmentDev Psychopathol200012215717510847622

- Meltzer-BrodySBrandonARPearsonBEvaluating the clinical effectiveness of a specialized perinatal psychiatry inpatient unitArch Womens Ment Health201417210711324201978

- CoxJLHoldenJMSagovskyRDetection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression ScaleBr J Psychiatry198715067827863651732

- KroenkeKSpitzerRLWilliamsJBThe PHQ-9J Gen Intern Med200116960661311556941

- SpitzerRLKroenkeKWilliamsJBLöweBA brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7Arch Intern Med2006166101092109716717171

- MundtJCMarksIMShearMKGreistJMThe Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioningBr J Psychiatry2002180546146411983645

- SnellenMMackKTrauerTSchizophrenia, mental state, and mother-infant interaction: examining the relationshipAust N Z J Psychiatry199933690291110619219

- KaySRPositive and Negative Syndromes in Schizophrenia: Assessment and ResearchNew YorkPsychology1991

- BerginkVLambregtse-van Den BergMPKoorengevelKMKupkaRKushnerSAFirst-onset psychosis occurring in the postpartum period: a prospective cohort studyJ Clin Psychiatry201172111531153721903022

- GuyWEarly Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology RevisedWashingtonDepartment of Health, Education, and Welfare1976

- YoungRCBiggsJTZieglerVEMeyerDAA rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivityBr J Psychiatry19781335429435728692

- NoorlanderYBerginkVvan den BergMPPerceived and observed mother-child interaction at time of hospitalization and release in postpartum depression and psychosisArch Womens Ment Health2008111495618270653

- WittenbornJRPsychiatric Rating Scales: ManualNew YorkPsychological Corporation1955

- KumarRHipwellAEDevelopment of a clinical rating scale to assess mother-infant interaction in a psychiatric mother and baby unitBr J Psychiatry1996169118268818363

- BrockingtonIFOatesJGeorgeSA screening questionnaire for mother-infant bonding disordersArch Womens Ment Health200134133140

- HipwellAEKumarRMaternal psychopathology and prediction of outcome based on mother-infant interaction ratings (BMIS)Br J Psychiatry199616956556618932898

- Gibaud-WallstonJDevelopment and Utility of the Parenting Sense of Competence ScaleNashvilleJohn F Kennedy Center for Research on Education and Human Development1978

- BroussardERHartnerMSFurther considerations regarding maternal perception of the first bornHellmuthJExceptional Infant: Studies in Abnormalities2New YorkBrunner/Mazel1971432449

- WanMGreenJThe impact of maternal psychopathology on child-mother attachmentArch Womens Ment Health200912312313419337701

- WolkeDPlay Observation Scheme and Emotion Rating (POSER) – ManualHatfield, UKUniversity of Hertfordshire1986

- CrittendenPMCARE-Index ManualMiamiFamily Relations Institute2003

- KennyMConroySParianteCMSeneviratneGPawlbySMother-infant interaction in mother and baby unit patients: before and after treatmentJ Psychiatr Res20134791192119823786913

- RiordanDApplebyLFaragherBMother-infant interaction in postpartum women with schizophrenia and affective disordersPsychol Med199929499199510473327

- MurrayLFiori-CowleyAHooperRCooperPThe impact of postnatal depression and associated adversity on early mother-infant interactions and later infant outcomeChild Dev1996675251225269022253

- PawlbySFernyhoughCMeinsEParianteCSeneviratneGBentallRMind-mindedness and maternal responsiveness in infant-mother interactions in mothers with severe mental illnessPsychol Med201040111861186920102664

- MeinsEFernyhoughCMind-Mindedness Coding ManualDurham, UKDurham University2006

- FieseBHPoehlmannJIrwinMGordonMCurry-BleggiEA pediatric screening instrument to detect problematic infant-parent interactions: initial reliability and validity in a sample of high-and low-risk infantsInfant Ment Health J2001224463478

- AbelKMWebbRTSalmonMPWanMWApplebyLPrevalence and predictors of parenting outcomes in a cohort of mothers with schizophrenia admitted for joint mother and baby psychiatric care in EnglandJ Clin Psychiatry2005666781789 quiz 808–78915960575

- MilgromJBurrowsGDSnellenMStamboulakisWBurrowsKPsychiatric illness in women: a review of the function of a specialist mother-baby unitAust N Z J Psychiatry19983256806869805591

- AngermeyerMCDietrichSPublic beliefs about and attitudes towards people with mental illness: a review of population studiesActa Psychiatr Scand2006113316317916466402

- WanMWSalmonMPRiordanDMApplebyLWebbRAbelKMWhat predicts poor mother-infant interaction in schizophrenia?Psychol Med200737453754617076915