Abstract

Unintended pregnancy is a significant global problem. In 2008, there were over 100 million unplanned pregnancies worldwide, representing approximately 41% of global conceptions. Family planning strategies in many countries are shifting from increasing the uptake of contraception among nonusers to increasing the uptake of the most effective methods among users of less effective methods. One of the most effective and acceptable methods of contraception is the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG IUS); however, its uptake varies widely by country. This article reviews the currently available LNG IUSs, the rationale for increasing uptake of these methods, and evidence regarding safety, and discusses counseling strategies to best inform women about this option for contraception.

Introduction

Unintended pregnancy is a significant global phenomenon. In a multinational study of over 80 countries, it is estimated that 41% of conceptions worldwide, over 100 million annually, are unplanned.Citation1 Rates vary by jurisdiction: 37% are unintended in Oceania, 38% in Asia, 44% in Europe, 48% in North America, and 63% in South America.Citation1 Rates of unintended pregnancy are declining in all jurisdictions except for North America.

One of the most effective options for pregnancy prevention is the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG IUS). Precise estimates of use of LNG IUS are difficult to obtain, as many countries report the use of any intrauterine contraception (IUC), a definition that includes both LNG IUS and copper intrauterine device (CuIUD). Worldwide, approximately 20% of women use IUC, but use varies widely; in Canada, about 1%–2% of women use IUC, whereas in China, 41% use IUC.Citation2 In most jurisdictions, use of IUC and LNG IUS is low, given their effectiveness, and increased uptake shows promise in making further reductions in unintended pregnancy rates.

This article reviews LNG IUSs with respect to their role in contraception, risk–benefit profile, and features that should be discussed with women considering this method.

The need for long-acting contraception: the Canadian experience

In Canada, precise estimates of unintended pregnancy are difficult to obtain, but a recent economic evaluation suggests that 39% of pregnancies are unintended, translating to over 180,000 unintended pregnancies and 65,000 unintended births annually.Citation3,Citation4 The direct medical cost of unintended pregnancy in Canada alone is approximately CAD 320 million, whereas raising unintended offspring costs Canadian families between CAD 4 and 15 billion.Citation3

Unintended pregnancy occurs in one of two settings: conception occurs among couples not using contraception or conception occurs as a result of contraceptive failure. In North America, 50% of unintended pregnancies occur as a result of contraceptive failure (due to either imperfect adherence or inherent method failure).Citation5

While it is important to inform women and couples about contraception, simply increasing contraceptive uptake is insufficient to make ongoing reductions in unplanned pregnancy in many jurisdictions. For instance, contraceptive use in Canada is high; among women who do not wish to conceive, 15% are not using contraception, whereas 20% are using a method inconsistently or incorrectly.Citation6 Contraceptive nonuse is more common among women at decreased risk of unintended pregnancy; they are more likely to be ambivalent about a pregnancy, older, less fertile, and have lower coital frequency.Citation7

Conversely, the most commonly used methods of contraception in Canada are condoms, combined oral contraception, and withdrawal.Citation6 These methods carry a typical-use failure rate of 18%, 9%, and 22%, respectively.Citation7,Citation8 IUC is uncommonly used in Canada relative to other countries.Citation6 Therefore, significant reductions in unintended pregnancy and its associated costs could be made if women switched from these less effective methods to the most effective methods.Citation4

A changing reproductive lifecycle

The needs of women with respect to family planning continue to change. Women born in the 1950s could expect to delay childbearing by 4 to 5 years from the onset of first intercourse.Citation9,Citation10 Since then, age at first intercourse has decreased slightly, but the age of first marriage and first childbirth has increased significantly. The median age of first childbirth in 2011 was 28.5 years, and the proportion of first births occurring in women over 30 years is increasing.Citation10 This means that young women can expect to delay childbearing by nearly 12 years from first intercourse. With such expectations for contraception, there is an increased need for the most effective options.

Furthermore, not all first marriages last forever. With decreasing rates of marriage, high rates of separation and divorce, and increasing subsequent marriages and long-term relationships, some, but not all, women may wish to preserve fertility rather than consider permanent contraception in the form of tubal sterilization.Citation11 Poststerilization regret is the most common complication following permanent contraception.Citation12 Thus, long-acting contraception (LAC; also called long-acting reversible contraception) shows potential at both ends of the reproductive lifecycle.

LNG IUS: an overview

An elegant and concise history of IUC is provided by Speroff and Darney in their clinical handbook for contraception.Citation13 In 1979, the first paper describing an LNG-releasing device in rhesus monkeys was published,Citation14 with the first human studies involving an LNG-releasing intrauterine device (IUD) published in 1980.Citation15 In the early 1980s, the first LNG IUS studies were published, which characterized the effectiveness and bleeding patterns of such devices.Citation16 A 1-year LNG IUS was produced with limited uptake. Thereafter, a 52 mg device with a daily release rate of 20 µg/day was approved in Finland in 1993 for conception control (LNG IUS 20, total content 52 mg; Mirena; Bayer AG, Leverkusen, Germany).Citation17

Currently available LNG IUS

There are several LNG IUSs available worldwide. The technical specifications are summarized in , with additional clinical information as follows.

Table 1 Key features of the commercially available LNG IUS

LNG IUS 20

The LNG IUS 20 (20 µg/day release rate, total content 52 mg/day; Mirena; Bayer AG) was first approved in 1993 in Finland, with approvals worldwide at different times. It is placed using a one-handed inserter with a 4.4 mm insertion tube.Citation18 LNG IUS 20 is considered the gold standard LNG IUS, with over 2,000 studies published on its many uses in gynecology and family planning. LNG IUS 20 is approved in most countries worldwide for contraception, in many countries for heavy menstrual bleeding, and in some countries for endometrial protection during hormone replacement therapy.

LNG IUS 8

In 2013, a smaller-framed device was approved for conception control for 3 years (LNG IUS 8 µg daily release rate, total content 13.5 mg; Jaydess/Skyla; Bayer Healthcare, Whippany, NJ, USA). It contains a small silver ring (to allow for differentiation between LNG IUS 20) and is placed with a one-handed inserter with an insertion tube of 3.8 mm diameter. It is approved only for conception control.Citation19

LNG20

In 2012, a new 52 mg LNG IUS was approved in the UK (LNG20, total content 52 mg; Levosert/Liletta; Allergan PLC, Irvine, CA, USA). The LNG20 has an initial daily release rate of 18.6 µg/day, and is placed with a two-handed inserter with an insertion tube of 4.8 mm diameter.Citation20 The device is currently undergoing phase III studies. The current duration of use is 3 years, but it will increase as phase III data show effectiveness. In countries where LNG20 is approved, it is less expensive than LNG IUS 20. It is approved for both conception control and heavy menstrual bleeding.

LNG IUS 9

In 2015, Bayer Healthcare submitted a New Drug Application to the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for LNG IUS 9 (total content 19.5 mg). This device has been approved by the FDA in September 2016.Citation21 As approval was obtained by the FDA at the time of final copyediting of this article, this device will not be discussed in detail. Published clinical data for LNG IUS 9 is available via phase II and III trials for both the 13.5 mg (LNG IUS 8) and 19.5 mg (LNG IUS 9) devices.Citation22,Citation23

Mechanism of action

The primary mechanism of contraceptive effect of all LNG IUSs is thickening of cervical mucus, which results in the impairment or inability of sperm to fertilize an oocyte.Citation18–Citation20 As such, LNG IUSs are not abortifacients.Citation24 Thickened cervical mucus may confer additional benefits to women, such as potentially reduced upper genital tract infection/pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).

The secondary mechanisms of action are clinically important but, in vivo, are not thought to play a significant role in preventing conception. Firstly and most notably, progestins cause endometrial decidualization and quiescence, leading to reduced and/or absent menstrual blood flow. While this also impairs endometrial receptivity of a blastocyst; this has not been demonstrated in vivo. Secondly, in some women, the progestin secretion of an LNG IUS is sufficient to prevent ovulation. Thirdly, progestins may impair tubal motility, reducing the potential fertile window of an oocyte. Fourthly, the presence of an intrauterine foreign body may accelerate apoptosis of spermatozoa, oocytes, and blastocysts through a sterile inflammatory response; this is more clearly understood with copper-containing devices as opposed to inert plastic devices. Furthermore, because progestins decrease prostaglandin production (a proposed mechanism by which dysmenorrhea is reduced), this mechanism of action may not exist for LNG IUS.Citation24

Key features

LNG IUSs share a set of common characteristics. LNG IUSs are highly effective LACs, with typical-use failure rates less than 0.5% of users.Citation8,Citation22,Citation24 Satisfaction is high among women who are accepting of reduced or absent menstrual flow.Citation25 They are also referred to as “forgettable” contraception, as they require almost no effort on the part of women to maintain adherence. Once removed, fertility is rapidly restored.Citation26,Citation27

Indications

The shared indication of all LNG IUSs is conception control, and is the focus of this review. Additional indications vary by country.Citation18–Citation20 The LNG IUS 8 (total content 13.5 mg) is approved for conception control in nulliparous and parous women for 3 years.Citation19 There are no other approved indications for this device, but it does reduce dysmenorrhea and may have additional clinical benefits which will evolve with time.Citation23 LNG20 (total content 52 mg) is currently approved for conception control and management of idiopathic heavy menstrual bleeding for 3 years.Citation20 As pivotal trials are ongoing, the duration of indication will change with time.

The established LNG IUS 20 (total content 52 mg) is approved for conception control for 5 years.Citation18 In many countries, it is also approved for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding, and in fewer countries, for endometrial protection during hormone replacement therapy.Citation18,Citation28 With the recent publication of a 7-year randomized controlled trial of the World Health Organization (WHO) showing effectiveness at 7 years, it is unclear if the duration of indication will change.Citation29 Additional unapproved uses of the LNG IUS 20 are too numerous to list in this paper.

In the original pivotal trials involving LNG IUS 20, only parous women were included,Citation14,Citation16 and as a result, in some product monographs, clinicians are advised that it is “not a first-line method” for nulliparous women. This is not an evidence-informed statement.Citation3,Citation24 While parity may be considered as part of patient counseling and device selection, it should not preclude a nulliparous woman of reproductive age from using an LNG IUS.

Contraindications

Contraindications, based on the WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria for contraceptive use (WHO-MEC), are listed in . The WHO-MEC assigns a rating out of 4 based on risk–benefit profile. A category 4 is a contraindication (previously considered absolute contraindication), whereas category 3 condition indicates that risk outweighs benefit (relative contraindication). Either the low-frequency providers should generally avoid prescribing a method to a woman with an MEC-3 or MEC-4 condition, or the woman should be referred for expert consultation.Citation29,Citation30

Table 2 Contraindications to use of an LNG IUS, based on the WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria

Safety

Addressing patient concerns

Despite the many positive features of IUC, and in particular, LNG IUS, uptake is low in many countries.Citation2,Citation3,Citation6 There are numerous barriers to uptake of IUC: systemic, clinician-driven, and patient-driven. A common barrier is related to the safety of such devices.Citation3 Addressing myths (held beliefs for which there are no data to support, or where data refute such beliefs) and misperceptions (where the risk is anticipated to be much higher or severe than evidence supports) can allay fears and improve adherence. Women who express dissatisfaction with counseling are more likely to discontinue their method.Citation7

When counseling regarding IUC use, I suggest responding to patient concerns clearly, using objective data and accurate estimates of risk, usually presented as numerical data, rather than being dismissive (“that’s not a problem at all”, “I’ve never had a patient experience that complication”) or alarmist (“it is a serious risk, but if you still want an IUD I will refer you”). Be mindful of agreeing with patients in a way that reinforces a misperception or myth (eg, Patient: “I hear IUDs cause infections” Clinician: “Yes, many patients share that concern”).

This section reviews the specific risks associated with LNG IUS use.

Failure

No method of contraception is 100% effective; however, the failure rates of intrauterine systems (IUSs) are among the lowest of all methods. The failure rate of LNG IUS 20 and LNG20 is effectively the same as female tubal sterilization.Citation8,Citation24 The failure rate of LNG IUS 8 (13.5 mg device) is 0.33 per 100 woman-years over the 3 years, and 0.31 for LNG IUS 16 (19.5 mg device), which is only slightly higher than the failure rate of sterilization, and is in stark contrast to the 9% failure rate of combined hormonal pills, patches, and rings.Citation8

In Canada, we recommend that typical-use failure rate be used when discussing any method of contraception, as this represents the “real-world” use of a method, and factors discontinuation and adherence.Citation12 While patients may offer an anecdote of a “friend” who experienced a failure of an IUD or IUS, I remind them that the rarity of such an event is what makes it memorable.

There are increasing data that show LNG IUSs continue to provide conception control beyond the approved indication.Citation29–Citation31 When insurance coverage and patient means permit, the device should be replaced at the end of its approved indication. However, if a woman has an IUS in situ beyond the approved duration and cannot afford another method, it may be reasonable to leave the device in situ for an additional duration of 1 year (LNG IUS 8) or 2 years (LNG IUS 20/LNG20) with informed discussion about a possibly increased risk of unintended pregnancy.

Pregnancy with an IUS in situ

When a pregnancy occurs with an IUS in situ, pregnancy options counseling should take place first. If the desire is for the pregnancy to continue, and the strings are visible, the IUS should be removed as soon as possible. If the desire is for abortion, the IUS should be removed (if possible) prior to medical abortion, or at the time of surgical abortion.Citation32 If strings are not seen, expulsion or perforation should also be considered as possible mechanisms for failure.

Ectopic pregnancy

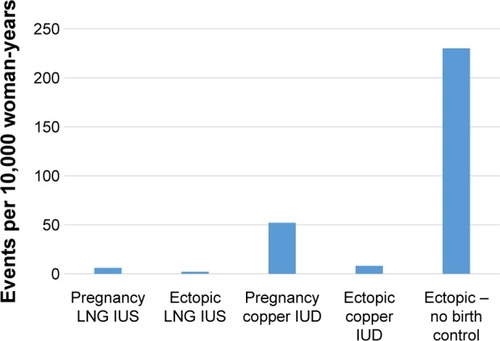

The ectopic pregnancy rate (number of ectopic pregnancies per year) is reduced among IUS users.Citation13 This is owing to the high effectiveness of IUSs. Like for CuIUDs and tubal sterilization, pregnancies that occur in the setting of a placed IUS are more likely to be ectopic than with a spontaneous conception. In the EURAS IUD study, a postmarketing surveillance study of IUD and IUS users, the proportion of ectopic pregnancies among conceptions in IUS users was 27%, versus 15% for CuIUD users.Citation33 As such, if a woman becomes pregnant with an IUS in situ, ectopic pregnancy must rapidly be ruled out. Because it can be confusing to compare absolute and conditional risks, a graphical representation of the incidence may be useful ().

Figure 1 Relative frequencies of intrauterine pregnancy and ectopic pregnancy in IUC users and in the general population.Citation33,Citation55

Pain

Fear of a painful placement is a common concern among women. In most cases, women experience little or no pain with placement. In a phase II study of two low-dose LNG IUSs, 57.9% experienced no or mild pain in the LNG IUS 20 cohort, and 72.3% experienced no or mild pain in LNG IUS 8/9 group.Citation23 In a study of over 2,000 women undergoing a first-time LNG IUS placement, the median level of pain on a 10 cm visual analog scale (10 cm = worst imaginable pain) was 1. Nulliparous women experienced more pain (mean 2.7 cm) than parous women (mean 1.9 cm), but, clinically, both are low.Citation34 We have seen similar results in our center.

Risk factors for pain during placement include a history of dysmenorrhea, history of cervical instrumentation, and a previous difficult insertion.Citation23,Citation24,Citation34 For all women, verbal reassurance (“vocal local”) and guidance throughout the placement can be extremely helpful. Distraction techniques (eg, coughing at the time of tenaculum placement) can also be useful.Citation24

The use of additional interventions to reduce pain with insertion shows minimal benefit.Citation35 Paracervical and intracervical blocks show limited benefit when performed routinely; these are best reserved for difficult placements. Misoprostol increases pain with insertion and should not be used routinely.Citation35

Perforation

Uterine perforation with IUC placement most often occurs at the time of insertion. However, migration is reported remote from a confirmed correct placement (likely due to perforation from a sound or device inserter prior to correct intrauterine placement).Citation36 While perforation is a common concern of women and clinicians, it is a rare complication. Reported rates of perforation vary in the literature; however, the largest cohort study that examined this complication was a postmarketing surveillance study in Europe of 61,000 women who received an IUS.Citation37 Among IUS users, the rate of perforation was 1.4 per 1,000 women (one in 714 placements). Risk factors for perforation include postpartum state and breastfeeding. Reassuringly, among 61,000 women, no woman experienced a life-threatening complication related to perforation. In this study, only LNG IUS 20 was studied. A subsequent study involving LNG IUS 8 is currently underway.

Infection

No review on IUC safety is complete without a nod to the Dalkon Shield, an inert plastic IUD that was associated with an increased incidence of PID, related to the multifilament string.Citation13 Since then, fears about PID related to IUC use have been difficult to alleviate.

Infections related to IUC placement are related to ascension of lower genital tract flora into the upper genital tract, and occur within the first 1 to 3 months following placement.Citation24 Conversely, in women with preexisting chlamydial infection, the presence of an IUC was not associated with an increased risk of PID when compared to those women without an IUC.Citation38

Infections following IUC placement are uncommon, affecting approximately 0.54% of insertions.Citation39 Rates of PID were similar among women who were unscreened, pre-screened, and screened at the time of IUC placement. Because it is more cost-effective, and potentially avoids the barrier of unnecessary pelvic examinations, same-day, risk factor-based screening (under 26 years, history of sexually transmitted infection [STI], or non-monogamy) is preferable.Citation39

Because the risk of PID is independent of the use of IUC, women with a history of STI and women who are at increased risk of STI can safely use an IUS. However, if a woman has mucopurulent cervical discharge, insertion should be delayed.Citation24

Infection with an IUS in situ

While uncommon, pelvic infections can occur with an IUS in situ. Asymptomatic infections can be treated while leaving the IUS in place.Citation24 One notable exception is when actinomyces or actinomyces-like effects are seen on a cervical cytology smear; in such cases, no treatment is warranted.

When mild-to-moderate PID occurs in a woman using an IUS, it should be left in situ while treatment is initiated. If a woman does not respond clinically within 48 hours, it should then be removed. In cases of severe PID (eg, tubo-ovarian abscess or sepsis), or if a woman requests removal at the time of diagnosis, it may be preferable to remove the IUS once IV antibiotic therapy has been established, to reduce the risk of seeding infection.

Expulsion

Expulsion occurs when the device is partially or completely extruded through the cervical os. It occurs most often in the first 1 to 3 months following placement, and is rare beyond this interval. The reported rates of expulsion are variable; most estimates are between 3 and 5%.Citation24 In a large US study of contraceptive users, IUD expulsions were more common in adolescents, but parity did not affect expulsion risk.Citation40 Post-placement ultrasonography should be reserved for difficult placements and when side effects or complications arise.Citation24

Low placement

In our center, we frequently receive consultations from clinicians who order routine scans, only to find that an IUS is “low”, either in the lower segment or in the cervix. If the woman is asymptomatic, it can be left in situ, and she should be instructed to perform string checks periodically. If a follow-up ultrasound is ordered, it should be repeated in 3 months, when many IUSs will migrate to the fundal position.Citation41 Because the mechanism of action of an IUS is cervical mucus thickening, it will function in a “low” position; this differs from CuIUDs, where sufficient intrauterine copper ion concentrations must be maintained to exert a contraceptive effect.Citation42

Infertility

A concern among many clinicians and younger women is that IUC use is associated with infertility.Citation43 Many studies examining IUC use and infertility examined the CuIUDs, and evidence for LNG IUS is more limited, though reassuring. Fertility is rapidly restored following removal of an IUS, with 80%–92% of women conceiving within a year of LNG IUS removal.Citation26 In a follow-up study of 69 IUC (50 LNG IUS) users and 42 nonusers, 12-month fertility rates were similar (81% former IUC user, 70% nonusers), and were actually higher among nulliparous IUC users than nonusers (92% versus 61%, P=0.02).Citation27 Women should be informed that fertility declines with age, and at the end of a 5-year device, older women may have experienced a decrease in ovarian reserve during that time.Citation12

Improving the patient experience

One barrier to IUC uptake is the perception that counseling regarding IUC/IUS is too lengthy for clinicians with limited time.Citation3 The US Contraceptive CHOICE study, which demonstrated high uptake of IUS and a resultant significant reduction in unintended pregnancy, provided structured counseling sessions for its participants, with a mean time of 12.9 minutes (range 4–32).Citation44 With some advanced preparation, repetition, and confidence, complete counseling regarding LNG IUS need not be lengthy.

Narrowing the options

Women who require contraception may benefit from access to general contraception counseling tools, such as videos or websites, prior to their appointment. In our clinic, women have the option of watching a short, non-branded video which outlines the currently available options, starting with the most effective options.

Various approaches and strategies for contraception counseling have been reported. A simple six-question approach (TIC-TAC, ) can be helpful to narrow the options down to one or two. A shared decision-making approach is preferred: one where the clinician and woman work together to find an optimal method.Citation45 In addition to effectiveness, side effects and adherence should be discussed. Once the method selection has been narrowed down, the woman should make the final choice.

Table 3 TIC-TAC approach to brief contraception method selection

Some women have previous experience with CuIUDs. Delineating the differences between the two devices may be helpful, and is summarized in .

Table 4 Differences between LNG IUS and copper IUDs

Patient selection

Most women can safely use LNG IUS. A list of contraindications is provided in . There are certain populations that warrant additional discussion, as they tend to be overlooked as IUS candidates.

Adolescents

Adolescents can expect to delay conception for 10 years or more from the onset of sexual activity.Citation9,Citation10 As such, they are excellent candidates for LAC. The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Society of Family Planning, and the American Academy of Paediatrics support the use of IUC in women of any age, including adolescent women.Citation24,Citation46–Citation48

Both the LNG IUS 20 and LNG IUS 8 have been studied in adolescents. In the Contraceptive CHOICE project, 31% of women under 20 years chose LNG IUS 20 (24.6% 14- to 17-year olds; 35.4% 18- to 19-year olds).Citation49 Continuation rate at 1 year was 81% among nulliparous women under 20 years.Citation50 A phase III LNG IUS 8 profiling study involving 303 adolescents (12- to 17-years old) was recently published. In this study, no pregnancies occurred at 1 year, and there were no cases of PID (there was a single case of endometritis, treated without complication).Citation51

Adolescents may benefit from additional counseling regarding menstrual changes with IUS and the safety of amenorrhea. Women worried about pain may benefit from the use of a smaller-framed device.Citation23

Nulliparous women

The initial trials for LNG IUS 20 included only parous women.Citation14,Citation16 In many jurisdictions, most notably Europe, the product labeling for IUS states that it is not a first-line contraceptive for nulliparous women.Citation52 However, this is not evidence-based. The Society of Family Planning and the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada state that IUC can be used as first-line therapy in nulliparous women.Citation24,Citation47

Perimenopausal women

The LNG IUS is a very good option for midlife women who require contraception. A common clinical question arises as to when the IUS should be removed if the woman is amenorrheic. Follicle-stimulating hormone will not be suppressed by progestin-only methods. If elevated above 35 IU/L over two readings, the woman should be considered menopausal, and the IUS can be removed. If the woman experiences vasomotor symptoms, estrogen replacement therapy (ET) can be initiated with an LNG IUS 20 or LNG20 in situ. Neither the LNG IUS 8 nor LNG IUS 9 has been studied for endometrial protection during ET; however, a 10 µg/day LNG menopausal intrauterine system (that was not marketed) demonstrated adequate endometrial protection during use of oral ET.Citation53

Informed consent

The benefits of an LNG IUS should be discussed with the woman, including the high effectiveness, low ease of adherence, and rapid reversibility. Potential beneficial effects on menses should be articulated as well. Clinicians should be sure to inform women of the material risks of an LNG IUS. Precise risk estimates are most useful, as they allow women to judge for themselves if this is a risk worth taking. The key risks are summarized as a rapid reference in .

Table 5 Key risks and risk estimates required for informed counseling regarding LNG IUS

Placement

A pelvic examination is not required until placement is to be attempted. In the product labeling for each of the IUSs, placement should occur within the first 7 days following a normal menstrual period. However, placement can occur anytime it is reasonably certain that a woman is not pregnant. A summary, as described in the WHO Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, is provided in . Urine pregnancy testing is not evidence-informed in most cases, and may miss very early conceptions. In instances where recent sexual activity has taken place, emergency contraception, such as a CuIUD, should be considered.

Table 6 Ruling out pregnancy prior to IUS insertion

The steps of placement should be reviewed with the woman, and any last-minute concerns should also be reviewed. Cleansing the cervix with antiseptic solution is optional.Citation24 We highly recommend the use of a tenaculum, as uterine traction will reduce the axis of a uterus, making insertion easier, and in some cases, possible. I ask patients to cough at the time of tenaculum to provide distraction. Few interventions have demonstrated significant reduction in pain at the time of IUS insertion; therefore, routine use of paracervical blockade is not recommended.Citation35

The uterus should be sounded prior to opening the sterile packaging. The minimum uterine depth should be 6 cm, and the maximum, 10 cm. If the depth is beyond 10 cm, perforation should be considered, and the procedure should be stopped.Citation36 If less than 6 cm, expulsion and malplacement are more likely. Sounding also provides a sense of the discomfort women will experience with IUS placement. I always warn women to expect discomfort at 4 cm on the sound; coaching women through the uncomfortable steps provides reassurance.

Once the arms are released from the IUS, a pause of ten seconds should take place before advancing the device to the fundus. The arms are slow to open in the uterus, and perforation may be reduced by waiting. Having women count, take deep breaths, and wiggle toes all seem to be effective options for distraction in our clinic.

Follow-up

A follow-up visit 6–12 weeks following placement allows the opportunity to review side effects, address concerns, and assess for adverse events. Routine string checks may be performed in some centers, though they only need to be performed if there is a concern.Citation54 Routine ultrasound is not recommended, and should be reserved for difficult insertions, or when clinically indicated.Citation24 Women should be informed of the date after which the IUS should be replaced.

Conclusion

LNG IUSs are highly effective, highly acceptable forms of LAC which can be used across the entire reproductive lifecycle. Increased uptake of LNG IUS has been shown to reduce unintended pregnancy, and has the potential to significantly reduce medical costs as well as societal costs from rising unintended births. Clinicians play an important role in reducing access barriers for women who need highly effective contraception and would consider an LNG IUS to meet this need.

Disclosure

Dustin Costescu did not receive any compensation (direct or in-kind) for the completion of this manuscript. He has served on national and international advisory boards for Bayer AG and Allergan PLC, both of whom manufacture LNG-containing intrauterine systems. The author reports no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SedghGSinghSHussainRIntended and unintended pregnancies worldwide in 2012 and recent trendsStud Fam Plann201445330131425207494

- World Health OrganizationWorld contraceptive use 2015 Available from: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/dataset/contraception/wcu2015.shtmlAccessed June 30, 2016

- HauckBCostescuDBarriers and misperceptions limiting widespread use of intrauterine contraception among Canadian womenJ Obstet Gynaecol Can201537760661626366817

- BlackAYGuilbertEHassanFThe cost of unintended pregnancy in Canada: estimating direct cost, role of imperfect adherence, and the potential impact of increased use of long acting reversible contraceptivesJ Obstet Gynaecol Can201537121086109726637081

- FinerLBHenshawSKDisparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001Perspect Sex Reprod Health2006382909616772190

- BlackAWangQWu WenSLalondeABGuilbertEFisherWContraceptive use among Canadian women of reproductive age: results of a national surveyJ Obstet Gynaecol Can200931762764019761636

- PazolKWhitemanMKFolgerSGKourtisAPMarchbanksPAJamiesonDJSporadic contraceptive use and nonuse: age-specific prevalence and associated factorsAm J Obstet Gynecol20152123324.e1324.e825305406

- TrussellJContraceptive failure in the United StatesContraception201183539740421477680

- FinerLBPhilbinJMTrends in ages at key reproductive transitions in the United States, 1951–2010Womens Health Issues2014243e271e27924721149

- Statistics CanadaFertility: fewer children, older moms Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-630-x/11-630-x2014002-eng.htmAccessed June 30, 2016

- Statistics CanadaMarital status: overview, 2011 Catalogue No. 91-201-X2013

- BlackAGuilbertDCostescuDCanadian contraception consensus (Part 2)J Obstet Gynaecol Can201537111033103926629725

- SperoffLDarneyPIntrauterine contraceptionA Clinical Guide for ContraceptionPhiladelphia, PALippincott Williams & Wilkins2011

- NilssonCGLähteenmäkiPLuukkainenTPatterns of ovulation and bleeding with a low levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine deviceContraception19802121551646768490

- WadsworthPFHeywoodRAllenDGSortwellRJWaltonRMTreatment of rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) with intrauterine devices loaded with levonorgestrelContraception1979202177184114355

- NilssonCGLuukkainenTDiazJAllonenHIntrauterine contraception with levonorgestrel: a comparative randomised clinical performance studyLancet1981182205775806110819

- LuukkainenTAllonenHHaukkamaaMLähteenmäkiPNilssonCGToivonenJFive years’ experience with levonorgestrel-releasing IUDsContraception19863321391483084167

- Bayer Healthcare CanadaMirena product monograph2014 Available from: http://omr.bayer.ca/omr/online/mirena-pm-en.pdfAccessed June 30, 2016

- Bayer Healthcare CanadaJaydess product monograph2014 Available from: http://omr.bayer.ca/omr/online/jaydess-pm-en.pdfAccessed June 30, 2016

- Allergan Specialty PharmaceuticalsLiletta prescribing information Available from: www.allergan.com/assets/pdf/liletta_piAccessed June 30, 2016

- Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals Press release Available from: http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/bayer-submits-new-drug-application-for-lcs-16-for-pregnancy-prevention-for-up-to-five-years-300182419.htmlAccessed June 30, 2016

- NelsonAApterDHauckBTwo low-dose levonorgestrel intrauterine contraceptive systems: a randomized controlled trialObstet Gynecol201312261205121324240244

- Gemzell-DanielssonKSchellschmidtIApterDA randomized, phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and MirenaFertil Steril201297361662222222193

- BlackAGuilbertECostescuDCanadian contraception consensus – chapter 7 – intrauterine contraceptionJ Obstet Gynaecol Can201638218222227032746

- PeipertJFZhaoQAllsworthJEContinuation and satisfaction of reversible contraceptionObstet Gynecol201111751105111321508749

- SivinISternJDiazSRates and outcomes of planned pregnancy after use of Norplant capsules, Norplant II rods, or levonorgestrel-releasing or copper TCu 380Ag intrauterine contraceptive devicesAm J Obstet Gynecol19921664120812131566771

- StoddardAMXuHMaddenTAllsworthJEPeipertJFFertility after intrauterine device removal: a pilot studyEur J Contracept Reprod Health Care201520322323025751567

- UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency/eMCMirena – summary of product characteristics (SPC) Available from: www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/1829/spc/mirenaAccessed June 30, 2016

- RowePFarleyTPeregoudovASafety and efficacy in parous women of a 52-mg levonorgestrel-medicated intrauterine device: a 7-year randomized comparative study with the TCu380AContraception201693649850626916172

- World Health OrganizationMedical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use5th edition2015 Available from: www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/family_planning/MEC-5/en/Accessed June 30, 2016

- CreininMDJansenRStarrRMGobburuJGopalakrishnanMOlariuALevonorgestrel release rates over 5 years with the Liletta 52 mg intrauterine systemContraception Epub2016425

- CostescuDGuilbertEBlackASOGC clinical practice guideline: medical abortionJ Obstet Gynaecol Can201638436638927208607

- HeinemannKReedSMoehnerSMinhTDComparative contraceptive effectiveness of levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices: the European Active Surveillance Study for Intrauterine DevicesContraception201591428028325601350

- HubacherDReyesVLilloSZepedaAChenPLCroxattoHPain from copper intrauterine device insertion: randomized trial of prophylactic ibuprofenAm J Obstet Gynecol200619551272127717074548

- LopezLMBernholcAZengYInterventions for pain with intrauterine device insertionCochrane Database Syst Rev20157CD00737326222246

- FergusonCACostescuDJamiesonMAJongLTransmural migration and perforation of a levonorgestrel intrauterine system: a case report and review of the literatureContraception2016931818626386445

- HeinemannKReedSMoehnerSMinhTDRisk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine DevicesContraception201591427427925601352

- JatlaouiTCSimmonsKBCurtisKMThe safety of intrauterine contraception initiation among women with current asymptomatic cervical infections or at increased risk of sexually transmitted infectionsContraception Epub201661

- SufrinCBPostlethwaiteDArmstrongMAMerchantMWendtJMSteinauerJENeisseria gonorrhea and Chlamydia trachomatis screening at intrauterine device insertion and pelvic inflammatory diseaseObstet Gynecol201212061314132123168755

- MaddenTMcNicholasCZhaoQSecuraGMEisenbergDLPeipertJFAssociation of age and parity with intrauterine device expulsionObstet Gynecol2014124471872625198262

- FaundesDPerdigaoAFaundesABahamondesLPettaCAT-shaped IUDs accommodate in their position during the first 3 months after insertionContraception200062416516811137069

- RatsulaKToivonenJLahteenmakiPLuukkainenTPlasma levonorgestrel levels and ovarian function during the use of a levonorgestrel-releasing intracervical contraceptive deviceContraception19893921952042495893

- PayneJBSundstromBDeMariaALA qualitative study of young women’s beliefs about intrauterine devices: fear of infertilityJ Midwifery Womens Health201661448248826971722

- MaddenTMullersmanJLOmvigKJSecuraGMPeipertJFStructured contraceptive counseling provided by the Contraceptive CHOICE ProjectContraception201388224324922959396

- DehlendorfCKrajewskiCBorreroSContraceptive counseling: best practices to ensure quality communication and enable effective contraceptive useClin Obstet Gynecol201457465967325264697

- Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group, The American College of Obstetricians and GynecologistsCommittee opinion no. 539: adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devicesObstet Gynecol2012120498398822996129

- Society of Family PlanningUse of the Mirena IUS and Paragard CuT380A intrauterine devices in nulliparous womenContraception201081:5201036737120399942

- American Academy of PediatricsContraception for adolescentsPediatrics20141344e1244e125625266430

- SecuraGMMaddenTMcNicholasCProvision of no-cost, long-acting contraception and teenage pregnancyN Engl J Med20143711413161323

- AbrahamMZhaoQPeipertJFYoung age, nulliparity, and continuation of long-acting reversible contraceptive methodsObstet Gynecol2015126482382926348177

- Gemzell-DanielssonKBuhlingKJDermoutSMLukkari-LaxEMontegriffoEApterDA Phase III, single-arm study of LNG-IUS 8, a low-dose levonorgestrel intrauterine contraceptive system (total content 13.5 mg) in postmenarcheal adolescentsContraception201693650751226872720

- Bayer Limited (Ireland)Mirena: summary of product characteristics Available from: http://www.medicines.ie/medicine/2707/SPC/Mirena+52mg+Intrauterine+Delivery+System/Accessed June 30, 2016

- RaudaskoskiTTapanainenJTomásEIntrauterine 10 microg and 20 microg levonorgestrel systems in postmenopausal women receiving oral oestrogen replacement therapy: clinical, endometrial and metabolic responseBJOG2002109213614411888095

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionU.S. selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2013: adapted from the World Health Organization selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2nd editionMMWR201362RR05146

- StulbergDBCainLRDahlquistILauderdaleDSEctopic pregnancy rates and racial disparities in the Medicaid population, 2004–2008Fertil Steril201410261671167625439806