Abstract

Djenkolism is an uncommon but important cause of acute kidney injury. It sporadically occurs after an ingestion of the djenkol bean (Archidendron pauciflorum), which is native to Southeast Asia. The clinical features defining djenkolism include: spasmodic suprapubic and/or flank pain; urinary obstruction; and acute kidney injury. The precise pathogenesis of acute kidney injury following djenkol ingestion remains unknown. However, it is proposed that an interaction between the characteristics of the ingested beans and the host factors causes hypersaturation of djenkolic acid crystals within the urinary system, resulting in subsequent obstructive nephropathy with sludge, stones, or possible spasms. We report a case of djenkolism from our rural clinic in Borneo, Indonesia. Our systematic literature review identified 96 reported cases of djenkolism. The majority of patients recovered with hydration, bicarbonate therapy, and pain medication. Three patients required surgical intervention; one patient required ureteral stenting for the obstructing djenkolic acid stones. Four of the 96 reported patients died from acute kidney failure. We stress the importance of awareness of djenkolism to guide medical practitioners in the treatment of this rare disease in resource-poor areas in Southeast Asia.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

Djenkolism is considered an uncommon but important cause of acute kidney injury in tropical Asia. Djenkolism sporadically results from the ingestion of the djenkol bean (Archidendron pauciflorum) (), native to Southeast Asia. Despite its strong smell, the beans are regarded as a delicacy in some areas, including Indonesia. They are consumed raw or prepared in a variety of ways. Djenkolism has a varied clinical presentation ranging from acute kidney injury, urinary obstruction, and spasmodic suprapubic and/or flank pain that occurs within hours of the bean’s ingestion. In this report, we describe a case of djenkolism in a remote clinical setting. We also conduct a systematic review of pertinent literature. We stress the importance of clinical findings and supportive care in remote areas where laboratory support is limited.

Case presentation

A 32-year-old man presented to our rural clinic in Borneo, Indonesia, with 10 hours of severe bilateral flank pain. Two hours after eating ten djenkol beans, the patient experienced acute, bilateral, severe (rated as 10/10), and spasmodic flank pain which radiated to the groin and was accompanied by vomiting. He also experienced difficulty with urination, hematuria, and decreased urine output (2 mL over the course of 12 hours).

The patient was healthy with no known medical problems. Medical history noted that the patient had experienced a similar episode as a teenager; he did not seek medical attention at that time and recovered after 14 days. The patient had consumed djenkol beans during the interval period between the two episodes without symptoms. He did not have any recent illnesses and had not taken medications prior to or since the onset of pain.

The patient was fully alert and in moderate distress. Vital signs were recorded at the time of treatment: blood pressure at 120/80; heart rate at 77 beats per minute; respiratory rate at 16 breaths per minute; and temperature at 36.5°C. The patient experienced approximately 2 minutes of severe spasmodic pain every 10 minutes with concurrent vomiting or syncope. Physical examination was notable for the odor of djenkol on his breath, abdominal hyperperistalsis, suprapubic tenderness, and bilateral costovertebral tenderness. Intravenous (IV) access was obtained and an indwelling urinary catheter was placed. The patient was given tramadol 50 mg IV for pain and urged to drink carbonated beverages as tolerated.

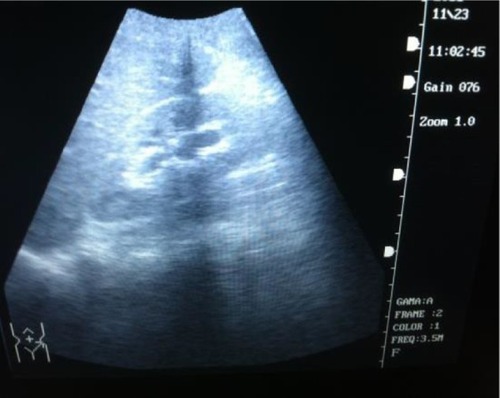

An ultrasound of the kidneys revealed bilateral hydronephrosis () with no stones noted. Anuria persisted and was treated with a 2.5 L normal saline bolus and furosemide 20 mg IV. The patient subsequently urinated 200 mL of bloody urine with resolution of pain. Upon microscopic exam, the initial urine sample had a specific gravity of 1.020 and 3+ blood, microscopic exam revealed many red blood cells and sediment but no crystals. The patient continued to receive pain medications and IV fluids as needed with resolution of oliguria.

After four days, the patient’s other symptoms, including hematuria, resolved. A repeat ultrasound demonstrated mild right-sided hydronephrosis and a normal left kidney. The patient was discharged on tramadol as needed, encouraged to drink at least 2 L of fluid per day, and advised to avoid djenkol beans. The patient returned approximately 2 weeks later completely asymptomatic; residual right-sided hydronephrosis had also completely resolved.

Literature review

A systematic literature review was conducted by searching Ovid MEDLINE, Index Medicus for Southeast Asia Region (IMSEAR), and Ovid Embase. IMSEAR is a database of articles published in selected journals within the World Health Organization Southeast Asian Region. Embase is an online database of biomedical literature published worldwide. The search strategy included medical subject headings (MeSH) terms: (dogfruit) OR (jenko*) OR (djenko*) OR (jering*) OR (jiringa*) OR (archidendron) OR (pauciflorum) OR (neang) OR (niang) OR (dog fruit) OR (Fabaceae).

Search results

The search on Ovid Medline and Embase resulted in 100 and 164 citations, respectively. The IMSEAR search yielded 16 citations, including ten unique citations. After removing duplicate citations, there were 172 unique articles. Five additional citations were found on reviewing bibliographies of the 172 articles, for a total of 177 references.Citation1–Citation6

Upon independent review of 177 articles by two authors (NEW and KPW) a total of 25 references were agreed upon as pertinent either in describing the cases or the clinical entity of djenkolism in terms of clinical presentation, differential diagnosis, pathophysiology, management, or outcome. References involving solely the biochemical study of djenkolic acid were excluded. Although we conducted the initial search in all languages, after identifying pertinent references, all but three (which were written before 1945) were available in English. Thus, we decided to limit our review to articles in the English language.

Many articles were reviews.Citation2–Citation7 We identified nine articles reporting a total of 96 cases in the Indonesian, Malaysian, Thai, and Singaporean literature.Citation3,Citation6,Citation8–Citation14 Some of the cases were cited by more than one article. We were able to obtain all but two of the original articles and only cited the original case report.

Details of available clinical, imaging, and laboratory data varied greatly ( and ). Three articles included 88 patients (with one study of 50 children), while other articles include only one to two cases each.Citation3,Citation6,Citation9 Demographics, physical examination, and findings were generally consistent with those found in the review literature, as well as in our patient case. Patient age ranged from 1.5–57 years with a male predominance (70%). The average number of beans consumed was ten; symptom onset occurred between 2 hours–4 days after ingestion. Major presenting signs and symptoms were: abdominal/loin/colicky pain, 70%; dysuria, 66%; oligouria, 59%; hematuria, 55%; and hypertension, 36%.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of reported cases of djenkolism

Table 2 Laboratory and imaging characteristics, treatment, and outcome of reported cases of djenkolism

While there was inconsistent reporting of needle-shaped crystals in the urine, hematuria was consistently reported in the literature. Some cases reported milky/turbid urine. When renal function was documented, creatinine was elevated, ranging from 1.7–14.1 mg/dL (normal, 0.6–1.3 mg/dL). When the blood count was completed, other electrolytes and inflammatory parameters were documented; these measures were normal. There was only one report of human renal biopsy in the English literature.Citation11 The majority of patients were treated with hydration and bicarbonate to alkalinize the urine. Cases in which conservative treatment failed were treated with: dialysis (one); surgery (one); urethral and bladder irrigation (one); or ureteral stenting (one). The mortality rate was (four out of 96) or about 4%. Three of the four deaths occurred in children; these deaths were attributed to renal failure with no availability of dialysis.Citation6

Discussion

Djenkol beans are a local delicacy in Indonesia, Malaysia, Southern Thailand, and Myanmar.Citation15 The djenkol tree grows up to 25 m in height. Djenkol pods are dark purple and contain three to eight round and flat beans per pod; they resemble flattened horse chestnuts.Citation3 The djenkol bean contains a large amount of the djenkolic acid in the range of 0.3–1.3 g/100 g wet weight; 93% of the acid exists in a free state.Citation16 The beans are eaten raw, fried, boiled, or roasted; sometimes, they are served as a dessert.Citation8 Regardless of the method of preparation, the ingestion of even one bean causes the breath and urine to have a sulfurous odor.Citation3

The clinical syndrome of djenkolism has a substantial male-to-female predominance (7:1) with an increased incidence from September–January, the rainy season, when the djenkol tree is in bloom.Citation10 Clinical djenkolism occurs sporadically. Individuals who have had djenkolism in the past do not necessarily have symptoms with subsequent ingestions, as was true in the case of our patient. Symptoms, if they do occur, occur within 2–12 hours of bean ingestion and consist of flank and bladder spasms, dysuria, colic, flatulence, vomiting, and diarrhea or constipation.Citation8 Affected persons can first develop a milky urine, which then consistently becomes bloody. Urine analysis demonstrates albumin, epithelial cells, casts, erythrocytes, and sometimes needle-shaped crystals.Citation8 Crystal formation is at least partially dependent on pH, as solubility of the djenkolic acid increases significantly in alkaline pH.Citation17

Djenkolism seems to have two presentations: 1) a mild presentation with pain and hematuria corresponding with transient ureteral obstruction with djenkolic acid crystals; and 2) a severe presentation in which hypertension, oliguria, and azotemia can occur. Anuria and death occur rarely.Citation11

In areas where laboratory tests are available, anuria corresponds with laboratory markers of acute kidney injury.Citation10 The clinical presentation of flank pain, nausea, vomiting, and gross hematuria is most compatible with ureteral and urethral obstruction by djenkolic acid crystals. Crystals may lacerate renal tissue and cause bleeding, or – in some cases – obstruction with sludge necessitates passage of a urethral catheter or stent.Citation13,Citation17

The pathogenesis of acute kidney injury following djenkol ingestion is not well understood. It is proposed to result from a combination of host factors, as well as characteristics of the specific beans ingested.Citation7 Hypersensitivity to a component of the bean has also been suggested to play an etiologic role in djenkolism, given the variability in the dose required for the development of nephrotoxicity.Citation3 While experiments in animals have been inconclusive, experiments in rats and mice resulted in clinicopathological findings compatible with acute tubular necrosis (ATN).

Obstruction of the renal tubules by crystals of djenkol acid has been suggested as a mechanism of ATN. Validation of this theory has been confounded by histological challenges: 1) acid crystals are not visible in all animal models (histologic preparation may dissolve the crystals);Citation17 and 2) renal biopsies are rarely performed on patients with acute djenkolism (one case report of human renal biopsy demonstrated findings of ATN).Citation11

In animal experiments, djenkolic acid crystals were detected in only a few animals, leading some to suggest that renal toxicity could be due to a direct toxic effect of the amino acid or a metabolite.Citation11 In conclusion, proposed major mechanisms of renal injury by the djenkol bean include hypersensitivity to or a direct toxic effect of a djenkol bean metabolite, resulting in acute kidney injury and/or urinary tract obstruction by djenkolic acid crystals, sludge, and/or possible ureteral spasms. In extreme cases, this can cause postobstructive failure. It is reasonable to also consider that the severe nausea and vomiting could contribute to dehydration, adding a prerenal element to the kidney injury.

There is a paucity of data on the long-term effects of hematuria secondary to chronic djenkol bean consumption. However, one study of children – those with microscopic asymptomatic hematuria – demonstrated that these children had four times the increased odds of djenkol bean exposure.Citation18

The patient seen in our clinic presented with classical findings associated with djenkol bean toxicity. Although we were unable to measure renal function due to lack of diagnostic tests in our rural Indonesian clinic, diagnosis of acute kidney injury in this patient was based on persistent oligouria/anuria following an ingestion of the bean. This scenario is not unusual in the remote areas where djenkol bean ingestion is common, and the diagnosis is made based on clinical presentation and limited laboratory data.

It is reported that the majority of cases resolve within 3 days with supportive care.Citation3 Mild djenkolism requires no specific treatment except pain control and hydration.Citation11 Severe djenkolism manifested by anuria and presumed acute kidney injury usually is managed with analgesia, aggressive hydration, and alkalinization of the urine with sodium bicarbonate to increase the solubility of djenkolic acid. Due to the lack of availability of sodium bicarbonate in our clinic, we used carbonated beverages to alkalinize the urine.Citation11,Citation12 Some cases of severe djenkolism with anuria do not respond to conservative therapy and require surgical intervention. There are case reports of the irrigation of the urethra, placement of urinary catheters, as well as stents to bypass or to resolve urinary obstruction caused by djenkolic acid, sludge, and calculi.Citation13,Citation17

Prevention of djenkolism is problematic. Incidence is low. The syndrome is sporadic, and it does not seem to be dependent on the quantity or mode of preparation of the beans. Individuals eating from the same dish do not all become symptomatic. Furthermore, an individual’s susceptibility to djenkolism and acute kidney injury from the bean is not fixed from one exposure to the next.Citation3,Citation8 It has been proposed that boiling the bean in dilute alkali would remove the acid.Citation12 However, the acceptance of this practice is unknown.

Conclusion

There is increasing awareness of the importance of and myriad of causes of acute kidney injury in the tropics. It is well established that djenkolism is an important cause of acute kidney injury in Southeast Asia.Citation2,Citation4,Citation7,Citation19 Awareness of this disease entity and an understanding of the clinical presentation, proposed pathophysiologic mechanisms, and recommended treatments of djenkolism are important to guide practitioners in resource-poor areas in Southeast Asia.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- AdlerSGWeeningJJA case of acute renal failureClin J Am Soc Nephrol20061115816517699203

- MathewAJGeorgeJAcute kidney injury in the tropicsAnn Saudi Med201131545145621911980

- ReimannHASukatonRUDjenkol bean poisoning (djenkolism); a cause of hematuria and anuriaAm J Med Sci1956232217217413339789

- SakujaVSudKAcute renal failure in the tropicsSaudi J Kidney Dis Transpl19989324726018408297

- SuharjonoADjenkol intoxicationPaediatr Indones19677290944885988

- SuharjonoASadatunOE“Djenkol” intoxication in childrenPaediatr Indones19688120295662186

- Eiam-OngSSitprijaVTropical plant-associated nephropathyNephrology199845–6313319

- AreekulSDjenkol bean, djenkolic acid and djenkolismJ Med Assoc Thai19796210530531501259

- Eiam-OngSSitprijaVSaetangPDjenkol bean nephrotoxicity in Southern ThailandGopalakrishnakonePTanCKProgress in Venom and Toxin Research. Proceedings of the First Asia Pacific Congress on Animal, Plant and Microbial ToxinsSingaporeNational University of Singapore Press1987628632

- H’ngPKNayarSKLauWMSegasothyMAcute renal failure following jering ingestionSingapore Med J19913221481492042077

- SegasothyMSwaminathanMKongNCBennettWMDjenkol bean poisoning (djenkolism): an unusual cause of acute renal failureAm J Kidney Dis199525163667810535

- WestCEPerrinDDShawDCHeapGHSoemantoDjenkol bean poisoning (djenkolism): proposals for treatment and preventionSoutheast Asian J Trop Med Public Health1973445645704274568

- WongJSOngTAChuaHHTanCAcute anuric renal failure following jering bean ingestionAsian J Surg2007301808117337378

- YongMCheongIJering-induced acute renal failure with blue urineTrop Doct1995251317886826

- BarcelouxDGDjenkol bean [Archidendron jiringa (Jack) I. C. Nielsen]Dis Mon200955636136419446679

- AreekulSKirdudomPChaovanaprichaKStudies on djenkol bean poisoning (djenkolism) in experimental animalsSoutheast Asian J Trop Med Public Health197674551558828979

- AreekulSMuangmanVBohkerdCSaenghirunCDjenkol bean as a cause of urolithiasisSoutheast Asian J Trop Med Public Health19789342743234890

- VachvanichsanongPLebelLDjenkol beans as a cause of hematuria in childrenNephron199776139429171298

- JhaVChughKSNephropathy associated with animal, plant, and chemical toxins in the tropicsSemin Nephrol2003231496512563601