Abstract

Pneumolabyrinth following temporal bone fracture is an extremely rare condition. It results from air entering the inner ear when a communication between the air-filled middle ear spaces and inner ear is established. The imaging modality of choice for pneumolabyrinth is high-resolution computed tomography of the temporal bone. Treatment options include conservative management (bed rest, antibiotics, corticosteroids) or surgery (exploratory tympanotomy). We present the case of a 31-year-old female who had pneumolabyrinth secondary to a temporal bone fracture. The patient was treated surgically and made a full clinical recovery.

Introduction

Pneumolabyrinth is a rare condition defined as the presence of air within the cochlea, vestibule, or semicircular canals, and represents radiological proof of a perilymphatic fistula.Citation1 A perilymphatic fistula is an abnormal communication between the air-filled middle ear spaces and the inner ear that allows escape of perilymph fluid.Citation1,Citation2

Pneumolabyrinth secondary to temporal bone fracture is exceedingly rare, and to our knowledge, only 14 previous cases have been reported.Citation1,Citation3–Citation11 The first radiological description of pneumolabyrinth was in 1984 by Mafee et al.Citation12 Four years later, Nurre et alCitation5 first described pneumolabyrinth occurring as a result of a temporal bone fracture.

Accepted causes of pneumolabyrinth are temporal bone fractures, barotraumatic pressure changes, and prior otological surgery. A pneumolabyrinth can be classified as follows: vestibular pneumolabyrinth, when the air bubbles are limited to the vestibule and/or the semicircular canals; cochlear pneumolabyrinth, when the air bubbles are limited to the cochlea; and combined pneumolabyrinth, when the air bubbles are found in both the vestibular organs and the cochlea. Patients may present with hearing loss, tinnitus, aural fullness and disabling vestibular symptoms. The imaging modality of choice for pneumolabyrinth is high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan of the temporal bones. Management of pneumolabyrinth is still controversial, and could be conservative or surgical. We report the case of a 31-year-old female with a radiologically confirmed pneumolabyrinth secondary to head trauma following a car accident. We also present a further review of the literature.

Case report

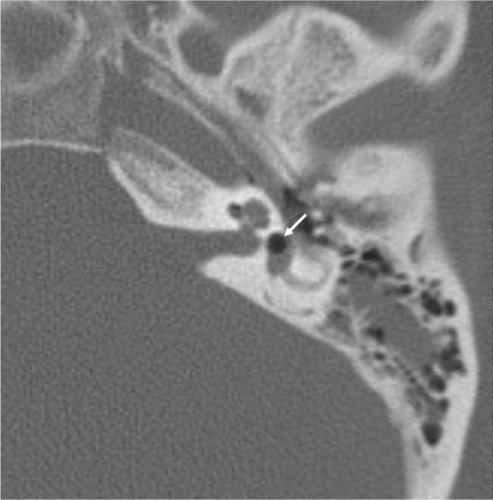

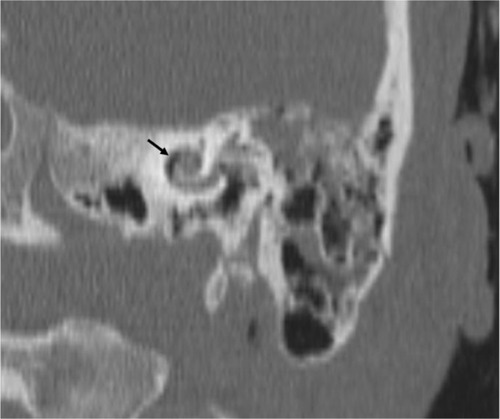

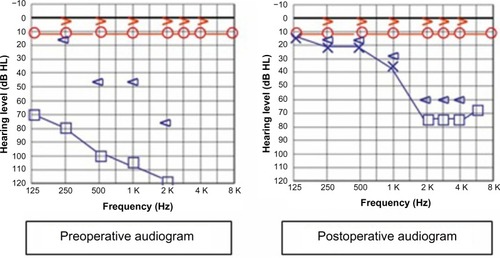

Informed consent from the patient and ethical approval was obtained for this study. A 31-year-old female who was sitting in the front passenger seat of a car without fastening her safety belt was admitted to the emergency room having been involved in a road traffic accident. Clinical and neurosurgical evaluation showed no evidence of intracranial injuries or systemic complications. CT scanning showed no evidence of intracranial complications. The patient was then referred to our department. On admission, the patient complained of left-sided hearing loss, bleeding from the ear, and severe vertigo. Otoscopic examination revealed lacerations in the anterior wall of the left external auditory canal and hemotympanum. A spontaneous nystagmus was also observed on the affected side. Pure-tone audiometry revealed a left-sided moderate to profound mixed hearing loss (). Auditory brainstem responses, electrocochleography, and vestibular tests were not performed. A high-resolution CT scan of the temporal bones demonstrated the presence of a left-sided longitudinal temporal bone fracture without involvement of the otic capsule, with mild opacification of the middle ear cavity and mastoid air cells. No abnormalities of the ossicular chain were noted. Axial CT scan and reformatted two-dimensional images obtained along the long axis of the petrous bone (Poschl plane) detected small foci of air density within the left vestibule and the basal turn of the cochlea ( and ). These findings were consistent with pneumolabyrinth. The patient was placed on bed rest with intravenous corticosteroids and antibiotics. The patient continued to have severe vertigo with vomiting despite 3 days of conservative treatment and hence a transcanal exploratory tympanotomy was performed. The ossicular chain was intact and the stapes was in its normal position without evidence of subluxation into the vestibule. However, a small fracture placed anteriorly to the anterior crus of stapes was seen at the footplate. Perilymph was seen escaping from the oval window area through the fracture. Fluid leakage was not observed at the round window. The oval window was sealed with fat taken from the ear lobule. The vestibular symptoms disappeared immediately after the surgery, but hearing recovery was slow. At her last follow-up visit, 12 months after surgery, audiometry showed improvement in both air and bone conduction thresholds, especially at frequencies between 250 and 1,000 Hz ().

Figure 1 Preoperative pure tone audiogram showing a left-sided mixed hearing loss. Postoperative pure tone audiogram showing marked improvement, especially in the lower frequencies.

Discussion

Pneumolabyrinth after temporal bone fracture is a rare phenomenon, and to date only 14 cases have been reported in the international literature.Citation1,Citation3–Citation11 According to the compiled literature (), pneumolabyrinth secondary to temporal bone fracture occurs more frequently in men, with a male to female ratio of 14:1. The mean age at the time of trauma was 25 (2–85) years. A transverse fracture of the temporal bone was detected in ten cases (66.7%), a longitudinal fracture in three cases (20%), and a mixed fracture in two cases (13.3%). A vestibular pneumolabyrinth was found in ten cases (71.4%) and a combined vestibular-cochlear pneumolabyrinth in the remaining four cases (28.6%). There were no cases of isolated cochlear pneumolabyrinth, and details were unavailable in one case. The most common reported symptoms include hearing loss (100%) followed by vertigo (73%) and tinnitus (33%).

Table 1 Review of the literature

High-resolution CT scan of the temporal bones with bone window in the axial and coronal planes is an extremely important tool for the diagnosis. The typical appearance of air inside the labyrinth is that of small black areas which can move within the inner ear space in response to changes in head position. Magnetic resonance imaging is not considered the technique of choice since neither air nor bone produce signals using this modality.

Due to the rarity of pneumolabyrinth, there has been no consensus regarding the management of the condition, which can be either conservative or surgical. In the literature, 50% of patients were treated surgically and 50% were treated conservatively. Conservative management includes bed rest, antibiotics, corticosteroids, and observation with serial CT scans. The aim of surgery is to close the connection between the inner ear and the air-filled middle ear spaces using fat, muscle, or fascia. In accordance with others, we believe that surgical exploration should be recommended for patients who show a progressive worsening of hearing function and/or persistent vestibular symptoms.Citation1,Citation8,Citation10 Patients with perilymphatic fistulas persisting for >7 days are significantly more likely to develop meningitis and this should be another reason to intervene surgically. In the present case, we undertook surgical exploration because of the persistent and disabling vestibular symptoms and a suspected perilymphatic fistula.

Vestibular symptoms are usually relieved after treatment (either conservative or surgical). This is presumably because of vestibular compensation or elimination of the irritant air bubble secondary to absorption of air. In contrast, hearing outcomes are more varied. In fact, hearing may improve, deteriorate, or remain stable.

Presence of air within the cochlea has been reported to result in a more severe and irrecoverable sensorineural hearing loss.Citation1 Kobayashi et alCitation13,Citation14 induced sensorineural hearing loss in animal models by introducing air bubbles into the labyrinth. They demonstrated that bubbles disturbed the propagation of the travelling wave of the basilar membrane. Further, the authors demonstrated that decreased cochlear function represented by cochlear potentials occurred after intrusion of air into the scala tympani, but was reversible when the air was expelled from the perilymph. In contrast, profound and irreversible hearing loss resulted after intrusion of air into the scala vestibule. They concluded that “it is possible that the prognosis is worse in cases with fistula of the oval window compared to that of the round window area, if the pneumolabyrinth is involved in the pathophysiology of perilymphatic fistula”. In our patient, surgical repair resulted in immediate improvement of vestibular symptoms and a slow but progressive recovery of hearing. This is in contrast with the observation of Prisman et alCitation1 who reported that surgical exploration and repair of perilymphatic fistula has been inconsistent in improving sensorineural hearing loss.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PrismanERamsdenJDBlaserSPapsinBTraumatic perilymphatic fistula with pneumolabyrinth: diagnosis and managementLaryngoscope2011121485685921305555

- LuYDZhangMMcCabeBFTube-perilymph fistula. An experimental studyChin Med J (Engl)199210543023051618012

- LipkinAFBryanRNJenkinsHAPneumolabyrinth after temporal bone fracture: documentation by high-resolution CTAJNR Am J Neuroradiol1985622942953920886

- YanagiharaNNishiokaIPneumolabyrinth in perilymphatic fistula: report of three casesAm J Otol1987843133183631238

- NurreJWMillerGWBallJBJrPneumolabyrinth as a late sequela of temporal bone fractureAm J Otol1988964894933232721

- WeissmanJLCurtinHDPneumolabyrinth: a computed tomographic sign of temporal bone fractureAm J Otolaryngol19921321131141642327

- LyosATMarshMAJenkinsHACokerNJProgressive hearing loss after transverse temporal bone fractureArch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg199512177957997598860

- GrossMBen-YaakovAGoldfarbAEliasharRPneumolabyrinth: an unusual finding in a temporal bone fractureInt J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol200367555355512697360

- WoodsonEASmithRJHBilateral pneumolabyrinth diagnostic for otic capsule fractures without high resolution imagingOtolaryngol Head Neck Surg2007137696997118036434

- de NegreirosJJrSampaioALSesanaWEOliveiraCAImaging case study of the month: traumatic pneumolabyrinthAnn Otol Rhinol Laryngol2008117970871018834076

- AdilEAChoudharyAKMoserKWGhossainiSNVestibular pneumolabyrinth: why assessment with temporal bone computed tomography utilizing dynamic focal spot mode is important for the diagnosisEmerg Radiol2011181434520827498

- MafeeMFValvassoriGEKumarAYanniasDAMarcusREPneumolabyrinth: a new radiologic sign for fracture of the stapes footplateAm J Otol1984553743756476089

- KobayashiTItohZSakuradaTShigaNTakasakaTEffect of perilymphatic air perfusion on cochlear potentialsActa Otolaryngol (Stockh)19901103–42092162239209

- KobayashiTSakuradaTOhyamaKTakasakaMInner ear injury caused by air intrusion to the scala vestibuli of the cochleaActa Otolaryngol (Stockh)199311367257308291430