Abstract

There are few reports of blowout fractures of the orbital floor in children younger than 5 years of age; in a search of the literature, we found only six reported cases which revealed the exact age, correct diagnosis, and treatment. We herein report the case of a 3-year-old boy with a blowout fracture of the orbital floor. Computed tomography showed a pure blowout fracture of the left orbital floor with a slight dislocation of the orbital contents. The patient was treated conservatively due to the absence of abnormal limitation of eye movement or enophthalmos. The patient did not develop any complications that necessitated later surgical intervention. Computed tomography at 6 months after the injury showed the regeneration of the orbital floor in the area of the fracture and no abnormalities in the left maxillary sinus. We herein present our case and the details of six other cases reported in the literature, and discuss their etiology, diagnosis, and treatment methods.

Introduction

Blowout fractures of the orbital floor are a frequent occurrence in adults, and the mechanisms of injuries, clinical presentations, and indications for treatment have been well described by numerous authors. However, there are few reports relating to blowout fractures of the orbital floor in children younger than 5 years of age. A search of the PubMed database using the term, “pediatric blowout fractures or blowout fractures in children”, revealed only six reports, in which the exact age, correct diagnosis, and treatment were noted.Citation1–Citation5 We experienced the case of a 3-year-old boy with a blowout fracture of the orbital floor. We herein present our case, along with the detailed information of six other cases that were reported in the literature, and discuss their etiology, diagnosis, and treatment methods.

Case report

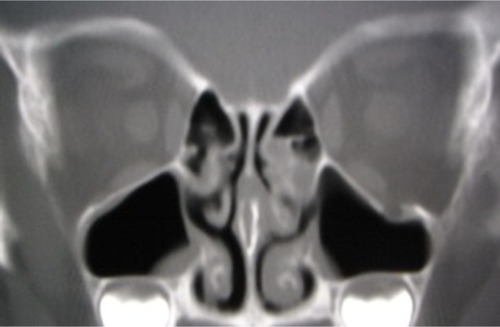

A boy of 3 years and 3 months of age was reported to have fallen from the front child seat of a bicycle. The boy’s mother reported no history of loss of consciousness or vomiting. The boy was taken to the neurosurgery section of a local hospital. A computed tomography (CT) scan was performed at the local hospital and showed a pure blowout fracture of the left orbital floor with a slight dislocation of the orbital contents. No brain abnormalities were observed. He was referred by the local hospital with an indication for surgery to repair his blowout fracture on the same day. A facial examination revealed no abnormalities with the exception of a small subcutaneous ecchymosis in the left lower eyelid. A medical examination revealed that there was no abnormal limitation of eye movement or enophthalmos (). A fundoscopy also revealed no abnormal findings in the vitreous body or the retina. Due to the lack of clinical symptoms, we selected the conservative option of observation without surgery. The patient did not develop any complications that necessitated later surgical intervention.

Figure 1 Computed tomography of a boy of 3 years and 3 months of age showing a pure blowout fracture of the left orbital floor with a slight dislocation of orbital contents.

CT at 6 months after the injury showed the regeneration of the orbital floor in the area of the fracture and no abnormal findings in the left maxillary sinus ().

Discussion

Blowout fractures of the orbital floor in early childhood have usually been reported either with other pediatric maxillofacial injuries, or in a series of injuries which include adults.Citation6–Citation10 In our search of the literature, the youngest reported patient that we could find was 11 months of age.Citation6 However, there have been few detailed case reports of blowout fractures of the orbital floor in children younger than 5 years of age. In this age period, the upper third of the developing face is more prominent and is more frequently exposed to injuries than the malar bone. Consequently, orbital roof fractures are more frequently encountered than orbital floor fractures.Citation11,Citation12 In our search of the literature, we could only find six case reports of blowout fractures of the orbital floor that mentioned the diagnosis, treatment, and results ().Citation1–Citation5

Table 1 The patient characteristics of young pediatric patients with blowout fractures of the orbital floor (n=7)

Three principal mechanisms have been proposed to explain the etiology of blowout fractures: globe-to-wall contact, hydraulic, and the buckling mechanism.Citation13 Pediatric patients, especially in early childhood, are most susceptible to the buckling mechanism due to a direct strike to the orbital rim.Citation14 The bones of children tend to bend, crack, and then snap back into place, resulting in linear or trapdoor fractures of the orbit. This transient buckling of the orbital walls tends to allow orbital soft tissue and extraocular muscle to herniate into the paranasal sinuses and become entrapped in the fracture region.Citation15 In this series, which includes our own patient, five linear and two trapdoor fractures were diagnosed from the CT images.

Five of the seven patients were male. A male predominance in this age group is apparent and is a reflection of the aggressive risk-taking behavior of young boys. Injuries by falling are the most common cause of isolated orbital fractures in children younger than 5 years of age. In this series, six of the seven fractures were caused by falling. In young children, falling is an indicator for the diagnosis of a blowout fracture. However, because of the uncooperative attitudes of children of this age and the relative paucity of clinical signs (such as orbital hematoma and sub conjunctival hemorrhage), a physical examination performed in the emergency room setting is of limited value in the diagnosis of suspected blowout fractures. In cases where patients present symptoms including post-traumatic diplopia, periorbital swelling and/or nausea, vomiting, which may be caused by extraocular muscle entrapment,Citation8 a CT examination of the orbit should be ordered.

When CT findings show a blowout fracture with extraocular muscle entrapment, as shown in case six, the early exploration and release of entrapped muscle is recommended by many authors to avoid ischemic necrosis, fibrosis, and the scarring of entrapped muscles.Citation1,Citation3,Citation8 Surgical intervention within the first day of the injury would seem to be the best treatment timing for the prevention of muscle fibrosis and has shown the best results.Citation5,Citation16,Citation17 In pediatric patients, however, the entrapment of the extraocular muscle may be significantly underestimated by CT examination.Citation18 Even if muscle entrapment is not indicated by CT, persistent diplopia after the resolution of initial edema is a further indication for surgical intervention, as shown in cases one and four.Citation3,Citation4 On the other hand, Pluijmers et alCitation4 reported one patient who required an operation due to late enophthalmos. In this case, a relatively wide trapdoor fracture might have been the cause of the late enophthalmos. In this age group, both the reestablishment of ocular movement and orbital volume are treatment goals.

In pediatric patients, the defects after entrapped orbital tissues are freed are often small; thus the reconstruction of the bone defects is not always necessary.Citation7 Orbital floor reconstruction might, however, be necessary if the bone defects are wide after the freeing of the entrapped orbital tissues. A question remains as to what sort of material can be used for orbital floor reconstruction in early childhood.Citation2,Citation4 Nonresorbable plate and sheet-like materials could disturb the normal growth of the facial bones. Alloplastic materials have been provided in some cases, but have also failed to achieve their purpose due to infection or rejection. Some authors have suggested that thin but strong and resorbable artificial materials would be ideal for orbital floor reconstruction in early childhood (which involves a rapidly growing and changing facial skeleton), and that this could eliminate the need for a second operative site (for the harvesting of an autologous bone graft) and eliminate the risk of complications at the donor site.Citation2,Citation4 In this case series, pericranium, Vicryl® sheet, and Lyoplant® were used in the reconstruction of the orbital floor.Citation1,Citation3,Citation4

While serious ocular or cerebral injuries and complications were not observed in any of the patients, complete ophthalmic and neurologic examinations are recommended in all cases when orbital blowout fractures are identified.Citation19 To determine the gold standard of treatment for blowout fractures in early childhood, the careful long-term follow-up of pediatric patients is also required.

Conclusion

In the present case series, falling was the most common cause of the orbital floor fractures in early childhood. In cases where patients present symptoms including diplopia, periorbital swelling, nausea and/or vomiting after injuries, a CT examination of the orbit should be ordered for appropriate diagnosis and treatment immediately.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- AndersonPJPooleMDOrbital fractures in young childrenJ Craniomaxillofac Surg19952331511547673441

- KlenkGKovacsABlow-out fracture of the orbital floor in early childhoodJ Craniofac Surg200314566667114501326

- EthunandanMEvansBTLinear trapdoor or “white-eye” blowout fracture of the orbit: not restricted to childrenBr J Oral Maxillofac Surg201149214214720466466

- PluijmersBIKoudstaalMJParidaensDvan der WalKGBlowout fracture in a 3-year-oldCraniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr20136213313624436749

- FouldsJSLaverickSMacEwenCJ‘White-eyed’ blowout fracture in childrenEmerg Med J2013301083623417267

- ConverseJMSmithBObearMFWood-SmithAOrbital blowout fractures: a ten-year surveyPlast Reconstr Surg196739120365335192

- LoseeJEAfifiAJiangSPediatric orbital fractures: classification, management, and early follow-upPlast Reconstr Surg2008122388689718766055

- BansagiZCMeyerDRInternal orbital fractures in the pediatric age group: characterization and managementOphthalmology2000107582983610811070

- CarrollSCNgSGOutcomes of orbital blowout fracture surgery in children and adolescentsBr J Ophthalmol201094673673920508048

- PosnickJCWellsMPronGEPediatric facial fractures: evolving patterns of treatmentJ Oral Maxillofac Surg19935188368448336220

- MessingerARadkowskiMAGreenwaldMJPenslerJMOrbital roof fractures in the pediatric populationPlast Reconstr Surg19898422132162748736

- KoltaiPJAmjadIMeyerDFeustelPJOrbital fractures in childrenArch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg199512112137513797488366

- SugamataAEtiology of blowout fracturesThe Journal of Tokyo Medical University20147211924

- LaneKPenneRBBilykJREvaluation and management of pediatric orbital fractures in a primary care settingOrbit200726318319117891646

- FujinoTMakinoKEntrapment mechanism and ocular injury in orbital blowout fracturePlast Reconstr Surg19806555715767367496

- YanoHMinagawaTMasudaKHiranoAUrgent rescue ‘missing rectus’ in blowout fractureJ Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg2009629e301e30418490210

- SugamataAYoshizawaNShimanakaKTiming of operation for blowout fractures with extraocular muscle entrapmentJ Plast Surg Hand Surg201347645445723848420

- ParbhuKCGallerKELiCMawnLAUnderestimation of soft tissue entrapment by computed tomography in orbital floor fractures in pediatric populationOphthalmology200811591620162518440640

- OppenheimerAJMonsonLABuchmanSRPediatric orbital fracturesCraniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr20136192024436730