Abstract

Because the pathophysiology of asthma has diverse characteristics, to manage the disease effectively, it is important for clinicians to distinguish among the clinical phenotypes. Among them, adult-onset asthma, that is, late-onset asthma (LOA), is increasing because of the aging of the population. The phenotype of LOA is largely divided into two types according to the presence or absence of eosinophilic inflammation, T-helper (Th)2- and non–Th2-associated LOA. Especially in Th2 LOA related to rhinosinusitis, as pulmonary function at onset is poor and asthma exacerbations occur frequently, it is important to detect this phenotype in the early phase by using a biomarker of Th2-type inflammation such as fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FENO). As non–Th2-LOA is often resistant to corticosteroids, this phenotype often requires another treatment strategy such as macrolide, diet, or smoking cessation. We often struggle with the management of LOA patients due to a lack of evidence; therefore, the elucidation of the mechanism of LOA contributes to increased efficiency of diagnosis and treatment of LOA. Age-related immune system and structural changes are thought to be associated with the pathophysiology of LOA. In the former case, changes in inflammatory cell function such as variations in the innate immune response and acquisition of autoimmunity or upregulation of oxidative stress are thought to be involved in the mechanism. Meanwhile, the latter can also become triggers or exacerbating factors of LOA via enhancement of airway hyperresponsiveness, decline in lung function, increased air trapping, and reduction in chest wall compliance. Therefore, appropriate individualized management in LOA may be possible through precisely assessing the pathophysiology based on age-related functional changes, including the immune and structural system.

Introduction

Many patients develop asthma during childhood; however, asthma symptoms can occur at any time in life. Several factors may make a person more likely to develop late-onset asthma (LOA). Citation1–Citation3 For example, women are more likely to develop asthma after the age of 20, and obesity also appears to increase the risk of developing asthma as an adult.Citation4 Moreover, individuals who had asthma as a child may see asthma recur later in life.Citation5 In any case, because of the worldwide population trend toward enhanced longevity, clinical concerns about LOA are developing and have been increasingly recognized by clinicians. However, the mechanisms that underlie the relationship between aging and asthma are still unclear and the condition is frequently underdiagnosed in older age groups.Citation6 In this review, we discuss these issues with a focus on the pathophysiology and treatment of LOA.

Clinical feature

Usually, asthma symptoms appear early in life. However, some people develop asthma symptoms for the first time in adulthood; their clinical status is called LOA, defined as: “asthma with onset of symptoms in adult life in a patient with no pre-existing, persistent respiratory symptoms,” but the definition of age has not been clarified.Citation7 It is reported that the age- and sex-adjusted incidence of newly diagnosed asthma in people older than 65 years was estimated by 0.1% per year.Citation8

Aging itself, however, has a significant effect on the methacholine response and has an impact on airway hyperreactivity.Citation9 Therefore, higher annual declines in FEV1 are observed in LOA,Citation10–Citation12 especially among elderly peopleCitation13 or smokers of over 10 pack-years.Citation14,Citation15 Obesity-associated LOA is characterized by lack of atopy, female predominance, and it is suggested that obesity may cause LOA through changes in the structure of the lung or in the function of the immune system.Citation16–Citation26 The above risk factors are characterized by chronic inflammation and oxidative stress, with an increase in the mediators of innate immunity. Women are more likely to be affected by LOA than men.Citation27 Possible explanations for gender differences in the rate of incidence of LOA may include endogenous and exogenous hormonal factors.Citation28 In addition, LOA is associated with worse lung function and lower atopic status.Citation10 Furthermore, among some patients with LOA, being elderly, having multi-comorbidities, polypharmacy, and poor inhaler technique, being inactive and home alone, as well as psychological status (depression, dementia, etc.)Citation29,Citation30 are beginning to be recognized as major issues. Actually, LOA is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease events.Citation31

At least 9%–15% of LOA can be attributed to occupational exposures, and one of the mechanisms may be related to work-related stress.Citation32 Mood disorders such as comorbid anxiety and depression are also associated with LOA.Citation33

Phenotype and endotype

Some studies proposed clinical sub-phenotypes of LOA based on cluster analyses.Citation34,Citation35 At first, LOA was split down the middle and phenotypes were classified into Th2-LOA or non–Th2-LOA.Citation36,Citation37 Th2-LOA is associated with sinusitis, nasal polyps, and, sometimes, aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD), but appears to be equally common in males and females.Citation38 This type is often severe from the onset and has been recently defined as uncontrolled asthma.Citation39 Non–Th2-LOA is associated with gender, obesity, smoking, and aging. However, because these analyses have been done using a cross-sectional study, the asthma variability has still not been fully examined. Therefore, a longitudinal-study is needed to clarify these complex phenotypes. Then, such analyses will become useful to predict the prognosis of LOA patients and to develop appropriate treatment strategies.Citation40 Ilmarinen et al identified five sub-phenotypes of LOA by using long-term follow-up (12-year) data.Citation40 This study suggested that identifying clusters with different disease prognoses is important for clinicians to determine the most effective treatment. In addition, fluctuations in lung function are a characteristic of asthma and represent a marker of brittle asthma.Citation41,Citation42 In this regard, detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA) has shown that intrinsic fluctuations in pulmonary function over time show a complex fractal-type behavior.Citation43 Kaminsky et al reported that identifying patients with similar fluctuation patterns and disease stability by using DFA could be helpful for personalized treatment.Citation44 Some patients with Th2-LOA have been reported to exhibit a distinct profile such as chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), air trapping, and male sex.Citation45 Air trapping is associated with high computed tomography sinus scores, and this phenotype is frequently associated with severe exacerbations, as mentioned earlier.Citation46 It is suggested that inflammation of the distal airways and that of paranasal sinuses are important predisposing factors for the development of exacerbations.Citation46 In such cases, systemic inflammation-targeted management, such as with monoclonal antibodies against anti-IL-5, might be an ideal treatment to prevent future exacerbations and lung function decline.Citation47 In this manner, by using biological markers in cluster analyses, we are able to explore disease pathogenesis by analyzing endotypes based on molecular characteristics and obtain novel guidelines for treatment of severe asthma. Furthermore, as we discuss later, it is assumed that age-related changes in immune function have an impact on the airway inflammation of LOA. This change exists in both innate and adaptive immunity cells. Especially, type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) are intimately related to LOA nasal polyps of patients with chronic nasal sinusitis.Citation48 Moreover, this endotype is related to interleukin (IL)-4,Citation49 IL-5, and IL-13.Citation50

Pathophysiology

Immune system

An increase in fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FENO), which can provide noninvasive assessment of airway inflammation, was found to be associated with advancing age.Citation51 The increase of the values may reflect the altered distribution of inflammatory cells or altered activity of inflammatory cells in the airway. Such altered activity may account for differences in clinical phenotypes between younger and older asthma subjects.Citation52 Th2-LOA with sinusitis is reported to be associated with ILC2.Citation48,Citation53,Citation54 One of the reasons could be that these cells represent a key factor in the mucoid innate immune response that boosts allergic inflammation.Citation55 Furthermore, these cells can be activated in an allergen-independent manner by IL-25, IL-33, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin, all of which are released from bronchial epithelial cells upon stimulation with air pollutants.Citation56 Actually, it is reported that they have a greater effect on LOA than on early-onset asthma (EOA).Citation57 Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin (SE) sensitization is known to be an independent risk factor in asthma,Citation58 and it is reported that SE-immunoglobulin (Ig) E sensitization with LOA in the elderly is associated with particularly severe eosinophilic asthma with CRS.Citation58–Citation63 Thus, it is suggested that SE–IgE sensitization could represent a clue to the pathogenesis of severe late-onset eosinophilic asthma in the elderly.Citation58,Citation64,Citation65 Matsumoto et al reported that, in women with asthma, the cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 gene (CysLTR1) variant might be associated with sensitization to SE and age at asthma onset.Citation66

Age-related declines in immune function, known as immunosenescence, also play a key role in the development of LOA. The immunosenescence process is boosted by oxidative stress through the increased rate of telomere shortening as a consequence of DNA damage. The coexistence of immunosenescence and viral infection promotes persistent inflammation.Citation67 The mechanism is suggested to represent diminished B-cell function.Citation68 In this condition, antigen persistence is enhanced, especially in the elderly, and pulmonary age-related inflammation is increased via cytokine or toll-like receptor without infection.Citation69 In addition, autoimmunity may increase the affinity of T cells to self-antigens or latent viruses, thereby promoting an autoimmune process.Citation70 In general, with age, naïve T lymphocytes in the thymic compartment as well as in the periphery are thought to decrease through thymic atrophy or loss of bone marrow function, including telomere shortening and impaired enzymes.Citation71 By contrast, with age, the numbers of memory T lymphocyte are reported to increase.Citation72,Citation73 These phenomena diminish the efficiency of T-cell activation.Citation72 However, when autoantibodies are increased in elderly individuals because of increased tissue damage and apoptosis, thymic T-regulatory cells (Tregs) become enhanced to regulate this autoimmunity.Citation74 As a result, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses are reduced, and susceptibility to infection increases. Recurrent infection stimulates proinflammatory cytokines, and this leads to activation of Tregs. Consequentially, the production of Th17 is enhanced, leading to persistent chronic inflammation. With increased age, total serum IgE is known to decrease because of impaired B–cell-mediated antibody production and specificity.Citation75 However, it is reported that the rate of allergen sensitization in older asthmatics is higher than that of age-matched controls.Citation76 The difference in B-cell activation which has caused such a status may play a potential role in autoimmunity. The risk of EOA and LOA is differently influenced by the interaction between childhood farming exposure and genetic variations.Citation77 A genetic variation, such as on chromosome 17q21, or the C–C chemokine regulated on activation, and normal T-cell expressed and secreted (RANTES) could play a part in the LOA.Citation78,Citation79 Age differences in the leukotriene (LT) and wingless/integrase (Wnt) pathways during airway inflammation underlie the differential development of airway remodeling.Citation80 Thirty-eight percent of asthmatics are reported to have paucigranulocytic type disease.Citation81 The mechanism is speculated to be derived from abnormalities or dysfunction of structural cells, such as airway smooth muscles and nerve. Therefore, increased bronchomotor tone from muscarinic and adrenergic pathways can cause symptoms, and a long-acting muscarinic antagonist might be effective therapy.Citation82 Bronchial thermoplasty (BT) is an endoscopic procedure that targets primarily airway remodeling and improves quality of life or exacerbation with asthmatics although pulmonary function is not improved.Citation83–Citation85 One of the mechanisms underlying the clinical improvement is related to alterations in different bronchial structures, such as airway smooth muscles and neuroendocrine cells, without any impact on eosinophilic inflammation.Citation86 Therefore, BT may be an option for paucigranulocytic type of severe LOA. Furthermore, murine mesenchymal stromal cells from the bone marrow are reported to have an impact on pulmonary inflammation; bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) following organ transplantation, stem/progenitor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (s/p HSCT), and immune dysregulation can contribute to the pathogenesis of LOA.Citation87,Citation88

Pulmonary structure and function

Additional data suggest that advanced age, irrespective of any concomitant pulmonary disease, is associated with increased bronchial hyperresponsiveness.Citation9,Citation89 In a study of 148 subjects, ranging from age 5 to 76 years, age had an independent association with bronchial hyperresponsiveness as measured by a methacholine challenge.Citation9 In another study, bronchial hyperresponsiveness to histamine challenge was associated with increased eosinophil count and allergic sensitization; however, older age maintained an independent association with bronchial hyperresponsiveness, which was more prominent in subjects with respiratory symptoms.Citation42 In addition to age, it is recognized that smoking and the baseline forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) have strong effects on bronchial hyperresponsiveness.Citation90,Citation91 Furthermore, aging is associated with a progressive decline in lung function.Citation92 Coupled with these findings, breathing is exaggerated through increased air trapping and a reduction in chest wall compliance with increased age.Citation93 Actually, it is reported that bronchodilators, such as long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA), have an add-on effect to inhaled corticosteroid (ICS).Citation94

Obesity

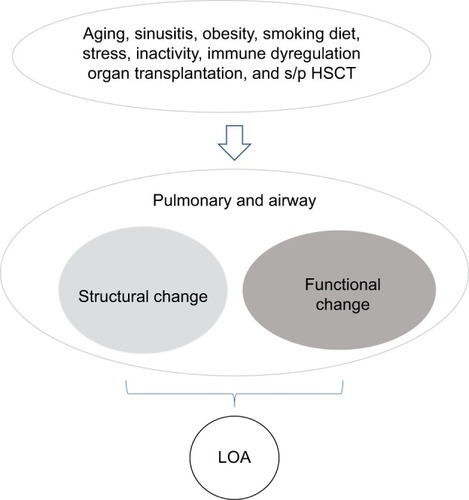

Obesity is characterized by chronic inflammation and oxidative stress, with an increase in the mediators of innate immunity.Citation95,Citation96 Obesity with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) is associated with an increase in the expression of IL-4 – homologous to lymphotoxins, exhibits inducible expression, competes with HSV glycoprotein D for herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM), which is a receptor expressed by T lymphocytes (LIGHT; homologous to lymphotoxins, exhibits inducible expression, competes with HSV glycoprotein D for HVEM, a receptor expressed by T lymphocytes), matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9, and CC chemokine receptor (CCR)-2. Following gastric bypass surgery and weight loss, the expression of these factors falls significantly.Citation97 In addition, obesity may lead to abnormal nitric oxide (NO) metabolism, with the imbalance of l-arginine and one of its methylated products known as asymmetric dimethyl arginine (ADMA) in obese subjects who acquire asthma after childhood. Therefore, in LOA, the plasma ratios of l-arginine to ADMA may explain the inverse relationship between body mass index (BMI) and FENO (reduced FENO bioavailability in obesity). This is thought to occur because ADMA can be an endogenous inhibitor of NO synthase (NOS) isoforms.Citation98 Actually, these lower l-arginine/ADMA ratios are associated with reduced lung function and increased respiratory symptoms, and may have a role in the pathobiology of LOA.Citation19 As another mechanism in the reduced value of FENO in obesity and asthma, it is thought that since excessive airway oxidative stress in obesity reacts with FENO, the valueof FENO is apparently low in such status.Citation99 It has been reported that, although similar cases have occurred among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), excessive nitrosative stress, such as NO, is generated in the peripheral airways.Citation100 The same can be said of the pathophysiology of LOA, and it has been suggested that the persistent elevation of exhaled NO in the distal airway of the asthma patient can be a therapeutic target.Citation101 However, in the actual clinical setting, ICS therapy cannot perfectly suppress the residual nitrosative stress elevation in the distal airways of asthmatics.Citation101 In short, it is speculated that nitrosative stress in the airways may be associated with actual steroid-resistance mechanisms in some asthmatic phenotypes, such as LOA. Therefore, it can be an option to select some drugs other than ICS, such as low-dose theophylline, which might be useful to reduce nitrosative stress.Citation102 Dietary change, such as a highly saturated meal poor in vitamin D, may contribute to the pathogenesis of asthma in obesity.Citation103,Citation104 High consumption of fish was reported to be protective, especially in the elderly.Citation105 A possible mechanism for the effect of fish consumption may be derived from long-chain ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), which inhibit arachidonic acid (AA) metabolism competitively via enzymatic pathways and suppress the production of active inflammatory eicosanoid mediators from AA.Citation106,Citation107 A schematic view of the pathophysiology in LOA is shown in .

Diagnosis and treatment

It is often difficult to distinguish between LOA and COPD, especially in the elderly, because both diseases have similar underlying mechanisms characterized by chronic airway inflammation and obstruction, which show analogous patterns of simple spirometric parameters. It should be taken into account that the reversibility of airway obstruction in elderly asthmatics is often reduced because of irreversible structural changes resulting from airway remodeling.Citation108 Therefore, precise pulmonary function tests such as total lung capacity or the carbon monoxide diffusing capacity of the lungs (DLCO) can help distinguish between these diseases.Citation109 Alternatively, it may be better to use chest imaging. Choi et al reported that, by using chest imaging biomarkers, LOA can be identified as an imaging-based phenotype.Citation110 It has been suggested that the imaging characteristics of LOA show airway luminal narrowing, reduced lung deformation, and increased air-trapping.

Usually, pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions (e.g., education) are prescribed based on the phenotype. Non-pharmacological interventions, such as encouraging smoking cessation and reducing body weight, should always be pursued whenever necessary.Citation111–Citation114 As for pharmacological treatments, ICS is absolutely essential for Th2-LOA.Citation115–Citation117 Th2-type biomarkers such as blood eosinophils, FENO, and periostin are used extensively to differentiate between Th2-LOA and non–Th2-LOA.Citation118,Citation119 Especially, for asthma and COPD overlapping, these biomarkers are useful for predicting the responsiveness to corticosteroids.Citation120–Citation124 However, when corticosteroid treatment is ineffective, the clinician should consider the possibility of poor inhaler technique because elderly patients with Th2-LOA often have functional disorders.Citation112,Citation125–Citation128 In such cases, assisted inhalation therapy by a caregiver might be a more useful strategy than self-administered ICS therapy.Citation128 This strategy dovetails with the result that, even when patients with LOA are elderly, their response to treatment is similar to that in patients with EOA.Citation118 Therefore, an upgrading strategy for poor adherence should be encouraged.Citation129,Citation130 If ICS treatment is truly ineffective, endotype target therapy should be taken into consideration.Citation131 Compared with placebo, reslizumab which is a monoclonal antibody against IL-5 produces greater reductions in asthma exacerbations and larger improvements in lung function in patients with LOA versus EOA.Citation132 Omalizumab improves all asthma outcomes independently of age, although the magnitude of the effects observed in the elderly seems to be lower than in other age groups.Citation133 Post hoc analyses of the anti-IgE agent omalizumab indicate similar efficacy in both younger and older adults. Anti-IL-5 and anti-IL-13 therapy appear to show even more pronounced effects as targeted treatments in late-onset disease and in asthmatic patients 65 years or older, but evidence is lacking.Citation45,Citation47,Citation134–Citation138 As yet, for non-eosinophilic asthma in the elderly, there is a lack of high-level evidence for targeted therapy, but macrolides may offer a viable option.Citation139

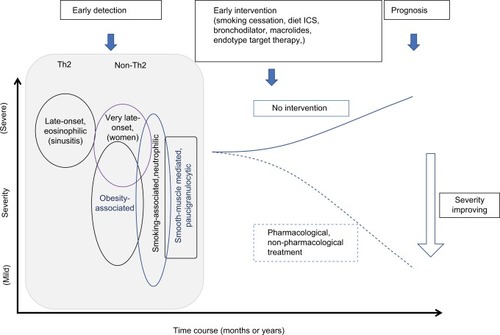

In , we show the time courses of LOA with or without intervention.

Figure 2 Time-course of LOA. The prognosis of LOA can be improved by early detection and precise intervention. Dotted and solid lines mean the time course of asthma severity by each intervention. Early intervention, such as pharmacological or non-pharmacological treatment, improve severity of asthma.

Conclusion

Today, advances in the understanding of the phenotypes and endotypes of asthma syndrome have helped us in managing these diverse subtypes of the disease. Because the community continues to age, LOA is beginning to play a larger role in asthma. As LOA shows different phenotypes with heterogenous backgrounds, appropriate individual management through estimating precisely the pathophysiology is required.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- SongWJKimSHLimSAssociation between obesity and asthma in the elderly population: potential roles of abdominal subcutaneous adiposity and sarcopeniaAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2012109424324823010229

- KimYKKimSHTakYJHigh prevalence of current asthma and active smoking effect among the elderlyClin Exp Allergy200232121706171212653160

- AmelinkMde GrootJCde NijsSBSevere adult-onset asthma: a distinct phenotypeJ Allergy Clin Immunol2013132233634123806634

- LvNXiaoLCamargoCAJrAbdominal and general adiposity and level of asthma control in adults with uncontrolled asthmaAnn Am Thorac Soc20141181218122425343191

- HerscherMLWisniveskyJPBussePJCharacteristics and outcomes of older adults with long-standing versus late-onset asthmaJ Asthma201754322322927459257

- EnrightPLMcClellandRLNewmanABGottliebDJLebowitzMDUnderdiagnosis and undertreatment of asthma in the elderly. Cardiovascular Health Study Research GroupChest1999116360361310492260

- AyresJGLate onset asthmaBMJ19903006740160216032196959

- BauerBAReedCEYungingerJWWollanPCSilversteinMDIncidence and outcomes of asthma in the elderly. A population-based study in Rochester, MinnesotaChest199711123033109041973

- HoppRJBewtraANairNMTownleyRGThe effect of age on methacholine responseJ Allergy Clin Immunol19857646096133902938

- MirandaCBusackerABalzarSTrudeauJWenzelSEDistinguishing severe asthma phenotypes: role of age at onset and eosinophilic inflammationJ Allergy Clin Immunol2004113110110814713914

- SorinoCBattagliaSScichiloneNDiagnosis of airway obstruction in the elderly: contribution of the SARA studyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012738939522848152

- Vaz FragosoCAGillTMRespiratory impairment and the aging lung: a novel paradigm for assessing pulmonary functionJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci201267326427522138206

- PorsbjergCLangePUlrikCSLung function impairment increases with age of diagnosis in adult onset asthmaRespir Med2015109782182725962648

- TommolaMIlmarinenPTuomistoLEThe effect of smoking on lung function: a clinical study of adult-onset asthmaEur Respir J20164851298130627660515

- ParkHWSongWJKimSHClassification and implementation of asthma phenotypes in elderly patientsAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol20151141182225455518

- WilliamsASMathewsJAKasaharaDIAugmented pulmonary responses to acute ozone exposure in obese mice: roles of TNFR2 and IL-13Environ Health Perspect2013121555155723434795

- MahadevSSalomeCMBerendNKingGGThe effect of low lung volume on airway function in obesityRespir Physiol Neurobiol2013188219219923770312

- LugogoNLHollingsworthJWHowellDLAlveolar macrophages from overweight/obese subjects with asthma demonstrate a proinflammatory phenotypeAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012186540441122773729

- HolguinFComhairSAHazenSLAn association between L-arginine/asymmetric dimethyl arginine balance, obesity, and the age of asthma onset phenotypeAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013187215315923204252

- BuskMBuskNPuntenneyPUse of continuous positive airway pressure reduces airway reactivity in adults with asthmaEur Respir J201341231732222835615

- Al-AlwanABatesJHChapmanDGThe nonallergic asthma of obesity. A matter of distal lung complianceAm J Respir Crit Care Med2014189121494150224821412

- ScottHAGibsonPGGargMLWoodLGAirway inflammation is augmented by obesity and fatty acids in asthmaEur Respir J201138359460221310876

- SidelevaOSurattBTBlackKEObesity and asthma: an inflammatory disease of adipose tissue not the airwayAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012186759860522837379

- PetersMCMcGrathKWHawkinsGANational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Severe Asthma Research ProgramPlasma interleukin-6 concentrations, metabolic dysfunction, and asthma severity: a cross-sectional analysis of two cohortsLancet Respir Med20164757458427283230

- DixonAEPoynterMEMechanisms of asthma in obesity. Pleiotropic aspects of obesity produce distinct asthma phenotypesAm J Respir Cell Mol Biol201654560160826886277

- BennettWDIvinsSAlexisNEEffect of obesity on acute ozone-induced changes in airway function, reactivity, and inflammation in adult femalesPLoS One2016118e016003027513854

- LeynaertBSunyerJGarcia-EstebanRGender differences in prevalence, diagnosis and incidence of allergic and non-allergic asthma: a population-based cohortThorax201267762563122334535

- de NijsSBVenekampLNBelEHAdult-onset asthma: is it really different?Eur Respir Rev201322127445223457164

- IlmarinenPTuomistoLENiemeläOComorbidities and elevated IL-6 associate with negative outcome in adult-onset asthmaEur Respir J20164841052106227540019

- MayorSAdult onset asthma may increase risk of heart disease and strokeBMJ2016354i4685

- TattersallMCBarnetJHKorcarzCEHagenEWPeppardPESteinJHLate-onset asthma predicts cardiovascular disease events: the Wisconsin sleep cohortJ Am Heart Assoc201659pii: e003448

- EngAMannetjeA’PearceNDouwesJWork-related stress and asthma: results from a workforce survey in New ZealandJ Asthma201148878378921864097

- LaborMLaborSJurićIFijačkoVGrleSPPlavecDMood disorders in adult asthma phenotypesJ Asthma201719

- WenzelSEAsthma phenotypes: the evolution from clinical to molecular approachesNat Med201218571672522561835

- MooreWCThe natural history of asthma phenotypes identified by cluster analysis. Looking for chutes and laddersAm J Respir Crit Care Med2013188552152223992583

- MooreWCMeyersDAWenzelSENational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research ProgramIdentification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research ProgramAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010181431532319892860

- BaptistAPRossJAClarkNMOlder adults with asthma: does age of asthma onset make a difference?J Asthma201350883684123782329

- WuWBleeckerEMooreWUnsupervised phenotyping of Severe Asthma Research Program participants using expanded lung dataJ Allergy Clin Immunol201413351280128824589344

- McDonaldVMGibsonPGExacerbations of severe asthmaClin Exp Allergy201242567067722515389

- IlmarinenPTuomistoLENiemeläOTommolaMHaanpääJKankaanrantaHCluster analysis on longitudinal data of patients with adult-onset asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol Pract201754967978e328389304

- AyresJGMilesJFBarnesPJBrittle asthmaThorax19985343153219741378

- HayataAMatsunagaKHiranoTStratifying a risk for an increased variation of airway caliber among the clinically stable asthmaAllergol Int201362334334923880616

- FreyUBrodbeckTMajumdarARisk of severe asthma episodes predicted from fluctuation analysis of airway functionNature2005438706866767016319891

- KaminskyDAWangLLBatesJHFluctuation analysis of peak expiratory flow and its association with treatment failure in asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2017195899399927814453

- de GrootJCStormHAmelinkMClinical profile of patients with adult-onset eosinophilic asthmaERJ Open Res201622pii: 00100-2015 eCollection 2016

- de GrootJCAmelinkMde NijsSBRisk factors for frequent severe exacerbations in late-onset eosinophilic asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2015192789990226426787

- PavordIDKornSHowarthPMepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialLancet2012380984265165922901886

- MjösbergJMTrifariSCrellinNKHuman IL-25- and IL-33-responsive type 2 innate lymphoid cells are defined by expression of CRTH2 and CD161Nat Immunol201112111055106221909091

- MjöosbergJBerninkJGolebskiKThe transcription factor GATA3 is essential for the function of human type 2 innate lymphoid cellsImmunity201237464965923063330

- MiljkovicDBassiouniACooksleyCAssociation between group 2 innate lymphoid cells enrichment, nasal polyps and allergy in chronic rhinosinusitisAllergy20146991154116124924975

- OlinACRosengrenAThelleDSLissnerLBakeBTorénKHeight, age, and atopy are associated with fraction of exhaled nitric oxide in a large adult general population sampleChest200613051319132517099006

- MathurSKAllergy and asthma in the elderlySemin Respir Crit Care Med201031558759520941659

- HongJYBentleyJKChungYNeonatal rhinovirus induces mucous metaplasia and airways hyperresponsiveness through IL-25 and type 2 innate lymphoid cellsJ Allergy Clin Immunol2014134242943924910174

- ShinHWKimDKParkMHIL-25 as a novel therapeutic target in nasal polyps of patients with chronic rhinosinusitisJ Allergy Clin Immunol2015135614761485e725725991

- DhariwalJCameronATrujillo-TorralboMBMRC-GSK Strategic Alliance ConsortiumMucosal type 2 innate lymphoid cells are a key component of the allergic response to aeroallergensAm J Respir Crit Care Med2017195121586159628085492

- WalkerJABarlowJLMcKenzieANInnate lymphoid cells--how did we miss them?Nat Rev Immunol2013132758723292121

- WuTJWuCFChenBYLeeYLGuoYLAge of asthma onset and vulnerability to ambient air pollution: an observational population-based study of adults from Southern TaiwanBMC Pulm Med20161615427094099

- BachertCvan SteenKZhangNSpecific IgE against Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins: an independent risk factor for asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol20121302376381e822738677

- SongWJSintobinISohnKHStaphylococcal enterotoxin IgE sensitization in late-onset severe eosinophilic asthma in the elderlyClin Exp Allergy201646341142126436720

- SchmidtFMeyerTSundaramoorthyNCharacterization of human and Staphylococcus aureus proteins in respiratory mucosa by in vivo- and immunoproteomicsJ Proteomics2017155313928099884

- KowalskiMLCieślakMPérez-NovoCAMakowskaJSBachertCClinical and immunological determinants of severe/refractory asthma (SRA): association with Staphylococcal superantigen-specific IgE antibodiesAllergy2011661323820973803

- HuvenneWCallebautIPlantingaMStaphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B facilitates allergic sensitization in experimental asthmaClin Exp Allergy20104071079109020214664

- BachertCZhangNHoltappelsGPresence of IL-5 protein and IgE antibodies to staphylococcal enterotoxins in nasal polyps is associated with comorbid asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol20101265962968968.e1e620810157

- KotzinBLLeungDYKapplerJMarrackPSuperantigens and their potential role in human diseaseAdv Immunol199354991668397479

- PatouJGevaertPVan ZeleTHoltappelsGvan CauwenbergePBachertCStaphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B, protein A, and lipoteichoic acid stimulations in nasal polypsJ Allergy Clin Immunol2008121111011517980412

- MatsumotoHKanemitsuYNagasakiTStaphylococcus aureus enterotoxin sensitization involvement and its association with the CysLTR1 variant in different asthma phenotypesAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol2017118219720328034578

- Al-AlawiMHassanTChotirmallSHAdvances in the diagnosis and management of asthma in older adultsAm J Med2014127537037824380710

- JohnsonSARozzoSJCambierJCAging-dependent exclusion of antigen-inexperienced cells from the peripheral B cell repertoireJ Immunol2002168105014502311994453

- van DuinDMohantySThomasVAge-associated defect in human TLR-1/2 functionJ Immunol2007178297097517202359

- VadaszZHajTKesselAToubiEAge-related autoimmunityBMC Med2013119423556986

- LintonPJDorshkindKAge-related changes in lymphocyte development and functionNat Immunol20045213313914749784

- HaynesLSwainSLWhy aging T cells fail: implications for vaccinationImmunity200624666366616782020

- PonnappanSPonnappanUAging and immune function: molecular mechanisms to interventionsAntioxid Redox Signal20111481551158520812785

- CandoreGDi LorenzoGMansuetoPPrevalence of organ-specific and non organ-specific autoantibodies in healthy centenariansMech Ageing Dev1997941–31831909147370

- MeyerKCThe role of immunity and inflammation in lung senescence and susceptibility to infection in the elderlySemin Respir Crit Care Med201031556157420941657

- KingMJBukantzSCPhillipsSMohapatraSSTamulisTLockeyRFSerum total IgE and specific IgE to Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, but not eosinophil cationic protein, are more likely to be elevated in elderly asthmatic patientsAllergy Asthma Proc200425532132515603205

- LauMYDharmageSCBurgessJAThe interaction between farming/rural environment and TLR2, TLR4, TLR6 and CD14 genetic polymorphisms in relation to early- and late-onset asthmaSci Rep201774368128262750

- MoffattMFGutIGDemenaisFGABRIEL ConsortiumA large-scale, consortium-based genomewide association study of asthmaN Engl J Med2010363131211122120860503

- HizawaNYamaguchiEKonnoSTaninoYJinushiENishimuraMA functional polymorphism in the RANTES gene promoter is associated with the development of late-onset asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2002166568669012204866

- DietzKde Los Reyes JiménezMGollwitzerESAge dictates a steroid-resistant cascade of Wnt5a, transglutaminase 2, and leukotrienes in inflamed airwaysJ Allergy Clin Immunol2017139413431354e627554815

- DemarcheSSchleichFHenketMPaulusVVan HeesTLouisRDetailed analysis of sputum and systemic inflammation in asthma phenotypes: are paucigranulocytic asthmatics really non-inflammatory?BMC Pulm Med2016164627044366

- PanettieriRAJrNeutrophilic and Pauci-immune phenotypes in severe asthmaImmunol Allergy Clin North Am201636356957927401627

- CoxGThomsonNCRubinASAIR Trial Study GroupAsthma control during the year after bronchial thermoplastyN Engl J Med2007356131327133717392302

- PavordIDCoxGThomsonNCRISA Trial Study GroupSafety and efficacy of bronchial thermoplasty in symptomatic, severe asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2007176121185119117901415

- CastroMRubinASLavioletteMAIR2 Trial Study GroupEffectiveness and safety of bronchial thermoplasty in the treatment of severe asthma: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled clinical trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010181211612419815809

- PretolaniMBergqvistAThabutGEffectiveness of bronchial thermoplasty in patients with severe refractory asthma: clinical and histopathologic correlationsJ Allergy Clin Immunol201713941176118527609656

- AbreuSCAntunesMAXistoDGBone marrow, adipose, and lung tissue-derived murine mesenchymal stromal cells release different mediators and differentially affect airway and lung parenchyma in experimental asthmaStem Cells Transl Med2017661557156728425576

- BergeronAGodetCChevretSBronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic SCT: phenotypes and prognosisBone Marrow Transplant201348681982423208317

- RijckenBSchoutenJPMensingaTTWeissSTDe VriesKVan der LendeRFactors associated with bronchial responsiveness to histamine in a population sample of adultsAm Rev Respir Dis19931476 Pt 1144714538503555

- BurneyPGBrittonJRChinnSDescriptive epidemiology of bronchial reactivity in an adult population: results from a community studyThorax198742138443497466

- PaolettiPCarrozziLViegiGDistribution of bronchial responsiveness in a general population: effect of sex, age, smoking, and level of pulmonary functionAm J Respir Crit Care Med19951516177017777767519

- MatsunagaKIchikawaTOkaAChanges in forced expiratory volume in 1 second over time in patients with controlled asthma at baselineRespir Med2014108797698224856920

- MatsunagaKAkamatsuKMiyatakeAIchinoseMNatural history and risk factors of obstructive changes over a 10-year period in severe asthmaRespir Med2013107335536023228369

- InoueHNiimiAMatsumotoHA 12-week, randomized, parallel-group, proof-of-concept study of tulobuterol patch and salmeterol inhaler as add-on therapy in adult-onset mild-to-moderate asthmaClin Exp Pharmacol Physiol20174412129

- HotamisligilGSShargillNSSpiegelmanBMAdipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistanceScience1993259509187917678183

- GhanimHAljadaAHofmeyerDSyedTMohantyPDandonaPCirculating mononuclear cells in the obese are in a proinflammatory stateCirculation2004110121564157115364812

- DandonaPGhanimHMonteSVIncrease in the mediators of asthma in obesity and obesity with type 2 diabetes: reduction with weight lossObesity (Silver Spring)201422235636223804543

- TranCTLeiperJMVallancePThe DDAH/ADMA/NOS pathwayAtheroscler Suppl200344334014664901

- HolguinFArginine and nitric oxide pathways in obesity-associated asthmaJ Allergy (Cairo)2013201371459523710196

- HiranoTMatsunagaKSugiuraHRelationship between alveolar nitric oxide concentration in exhaled air and small airway function in COPDJ Breath Res20137404600224091810

- HiranoTMatsunagaKSugiuraHPersistent elevation of exhaled nitric oxide and modification of corticosteroid therapy in asthmaRespir Investig20135128491

- HiranoTYamagataTGohdaMInhibition of reactive nitrogen species production in COPD airways: comparison of inhaled corticosteroid and oral theophyllineThorax200661976176616936236

- WoodLGGargMLGibsonPGA high-fat challenge increases airway inflammation and impairs bronchodilator recovery in asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol201112751133114021377715

- PaulGBrehmJMAlcornJFHolguínFAujlaSJCeledónJCVitamin D and asthmaAm J Respir Crit Care Med2012185212413222016447

- UddenfeldtMJansonCLampaEHigh BMI is related to higher incidence of asthma, while a fish and fruit diet is related to a lower- Results from a long-term follow-up study of three age groups in SwedenRespir Med2010104797298020171076

- DavisBCKris-EthertonPMAchieving optimal essential fatty acid status in vegetarians: current knowledge and practical implicationsAm J Clin Nutr2003783 Suppl640S646S12936959

- ChungHNettletonJALemaitreRNFrequency and type of seafood consumed influence plasma (n-3) fatty acid concentrationsJ Nutr2008138122422242719022967

- BousquetJJefferyPKBusseWWJohnsonMVignolaAMAsthma. From bronchoconstriction to airways inflammation and remodelingAm J Respir Crit Care Med200016151720174510806180

- SinBAAkkocaOSaryalSOnerFMisirligilZDifferences between asthma and COPD in the elderlyJ Investig Allergol Clin Immunol20061614450

- ChoiSHoffmanEAWenzelSENational Heart, Lung and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research ProgramQuantitative computed tomographic imaging-based clustering differentiates asthmatic subgroups with distinctive clinical phenotypesJ Allergy Clin Immunol20171403690700e828143694

- EisnerMDYelinEHKatzPPShiboskiSCHenkeJBlancPDPredictors of cigarette smoking and smoking cessation among adults with asthmaAm J Public Health20009081307131110937016

- GibsonPGMcDonaldVMMarksGBAsthma in older adultsLancet2010376974380381320816547

- ParkHWKimTWSongWJPrediction of asthma exacerbations in elderly adults: results of a 1-year prospective studyJ Am Geriatr Soc20136191631163224028367

- WesterhofGAVollemaEMWeersinkEJReinartzSMde NijsSBBelEHPredictors for the development of progressive severity in new-onset adult asthmaJ Allergy Clin Immunol2014134510511056e224954263

- SinDDTuJVInhaled corticosteroid therapy reduces the risk of rehospitalization and all-cause mortality in elderly asthmaticsEur Respir J200117338038511405515

- SlavinRGHaselkornTLeeJHZhengBDenizYWenzelSETENOR Study GroupAsthma in older adults: observations from the epidemiology and natural history of asthma: outcomes and treatment regimens (TENOR) studyAnn Allergy Asthma Immunol200696340641416597074

- HaughneyJAubierMJørgensenLComparing asthma treatment in elderly versus younger patientsRespir Med2011105683884521435854

- MatsunagaKAkamatsuKHiranoTIchinoseMResponse to treatment in individuals with late-onset asthmaJ Am Geriatr Soc20126081587158822889028

- MatsusakaMKabataHFukunagaKPhenotype of asthma related with high serum periostin levelsAllergol Int201564217518025838094

- AkamatsuKMatsunagaKSugiuraHImprovement of airflow limitation by fluticasone propionate/salmeterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: what is the specific marker?Front Pharmacol201123621811461

- KunisakiKMRiceKLJanoffENRectorTSNiewoehnerDEExhaled nitric oxide, systemic inflammation, and the spirometric response to inhaled fluticasone propionate in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective studyTher Adv Respir Dis200822556419124359

- ZietkowskiZKucharewiczIBodzenta-LukaszykAThe influence of inhaled corticosteroids on exhaled nitric oxide in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseRespir Med200599781682415939243

- FerreiraIMHazariMSGutierrezCZamelNChapmanKRExhaled nitric oxide and hydrogen peroxide in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effects of inhaled beclomethasoneAm J Respir Crit Care Med200116461012101511587988

- KupczykMHaqueSMiddelveldRJDahlénBDahlénSEBIOAIR InvestigatorsPhenotypic predictors of response to oral glucocorticosteroids in severe asthmaRespir Med2013107101521153023993706

- TuranOTuranPAMiriciAParameters affecting inhalation therapy adherence in elderly patients with chronic obstructive lung disease and asthmaGeriatr Gerontol Int2017176999100527426234

- WieshammerSDreyhauptJDry powder inhalers: which factors determine the frequency of handling errors?Respiration2008751182517911976

- MelaniASBonaviaMCilentiVGruppo Educazionale Associazione Italiana Pneumologi OspedalieriInhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease controlRespir Med2011105693093821367593

- MatsunagaKYamagataTMinakataYIchinoseMImportance of assistance by caregivers for inhaled corticosteroid therapy in elderly patients with asthmaJ Am Geriatr Soc200654101626162717038090

- UlrikCSLate-onset asthma: a diagnostic and management challengeDrugs Aging201734315716228164255

- BurdonJAdult-onset asthmaAust Fam Physician201544855455726510141

- SklootGSAsthma phenotypes and endotypes: a personalized approach to treatmentCurr Opin Pulm Med20162213926574717

- BrusselleGGerminaroMWeissSZangrilliJReslizumab in patients with inadequately controlled late-onset asthma and elevated blood eosinophilsPulm Pharmacol Ther201743394528159511

- SposatoBScaleseMLatorreMEffects of omalizumab in severe asthmatics across ages: a real life Italian experienceRespir Med201611914114927692136

- RubinsztajnRChazanRMonoclonal antibodies for the management of severe asthmaAdv Exp Med Biol2016935354227334730

- PiperEBrightlingCNivenRA phase II placebo-controlled study of tralokinumab in moderate-to-severe asthmaEur Respir J201341233033822743678

- OrtegaHGLiuMCPavordIDMENSA InvestigatorsMepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthmaN Engl J Med2014371131198120725199059

- BelEHWenzelSEThompsonPJSIRIUS InvestigatorsOral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of mepolizumab in eosinophilic asthmaN Engl J Med2014371131189119725199060

- GevaertPVan BruaeneNCattaertTMepolizumab, a humanized anti-IL-5 mAb, as a treatment option for severe nasal polyposisJ Allergy Clin Immunol20111285989995e1e821958585

- de RoosEWIn ‘t VeenJCBraunstahlGJLahousseLBrusselleGGTargeted therapy for older patients with uncontrolled severe asthma: current and future prospectsDrugs Aging201633961962827638817