Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this study was to assess respiratory health and airway and systemic inflammation in professional forest firefighters post firefighting.

Methods

A total of 60 firefighters who participated in forest firefighting operations in Greece during 2008 were included in the study. A questionnaire consisting of symptoms and exposure, pulmonary function, atopy, bronchial hyperresponsiveness, and markers of inflammation in induced sputum, serum, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was assessed.

Results

A measurable eosinophilic and neutrophilic inflammation was shown to be induced in the bronchial airways after acute exposure during forest firefighting. This was associated with increased respiratory symptoms from the upper and lower respiratory tract and pulmonary function impairment. Additionally, a measurable systemic inflammatory response was demonstrated. This study showed that acute exposure during forest firefighting significantly augments the intensity of airway and systemic inflammation in relation to the baseline inflammatory background due to chronic exposure.

Conclusion

The repeated acute exposures during firefighting augment the burden of chronic airway and systemic inflammation and may eventually lead to allergic sensitization of the airways and increased incidence of rhinitis and asthma after prolonged exposure.

Introduction

Professional firefighters have prolonged exposure to smoke and to a complex mixture of particulate matter and irritant gases that are directly inhaled.Citation1,Citation2 It is well established that the use of self-contained breathing apparatuses (SCBAs) during firefighting reduces occupational exposure to fire smoke.Citation3 However, these devices are often not used, letting exposure be a major concern. Firefighting has been associated with increased respiratory symptoms,Citation4,Citation5 acute respiratory obstruction,Citation6–Citation8 and, in some occasions, increased bronchial hyperresponsiveness.Citation9,Citation11 Furthermore, some studies suggest that smoke inhalation leads to allergic sensitization and airway inflammation.Citation12,Citation13 Noteworthy, apart from the local inflammatory responses in the airways, a measurable systemic inflammatory response is also induced.Citation13–Citation16 Data from firefighters who participated in the World Trade Center incident clearly revealed an association between the intensity of the exposure and the effect on pulmonary function parametersCitation17 and persisting airway hyperresponsiveness.Citation9,Citation18 Our group has shown an association between the occupational years and the intensity of airway and systemic inflammation.Citation13 Furthermore, a positive association has been shown between the number of fires fought in the previous year and the presence of bronchial hyperresponsiveness and the risk of irritant-induced asthma.Citation4

Few studies have examined the pre- and postexposure airway and systemic inflammation in forest firefighters. The aim of this study was to assess postexposure respiratory health and inflammation in professional firefighters with acute exposure to forest fire smoke.

Methods

Study population

We assessed the effect of intensive exposure to fire smoke on airway and systemic inflammation in a group of 60 firefighters who participated in forest firefighting operations for several days continuously.

Firefighters were administered a standardized questionnaire assessing lifetime chronic respiratory conditions, history of tobacco use, history of symptoms during firefighting and during the interval periods, volunteer firefighter status, and lifetime occupational history. Symptom records included cough, wheezing, sputum production, shortness of breath or chest tightness, and shortness of breath while walking, as well as various eye, nose, and throat symptoms.

Each subject attended the laboratory on two separate visits within a week. On visit one (24–48 hours post exposure), blood sampling, reversibility test, and sputum induction were performed. On visit two (at least 48 hours apart visit one), patients underwent methacholine provocation challenge and skin-prick tests. Bronchoscopy was performed in a subgroup of 12 firefighters who volunteered after signing an informed consent.

The same group of firefighters was reassessed off-season, with an interval time between postexposure and off-season measurements of 3 months. All subjects gave informed consent for the participation in the study, which was approved by the ethics committee of “Sotiria” Hospital for Diseases of the Chest.

Reversibility test

Lung function (forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1]/forced vital capacity [FVC]) was measured with a dry wedge spirometer (MasterScreen; Jaeger, Hoechberg, Germany) according to standardized guidelines.Citation19 Measurements were always performed by the same technician using the same spirometer. The reversibility test was performed 20 minutes after inhalation of 200 μg salbutamol via a metered dose inhaler. Subjects were instructed not to use short-acting bronchodilators for 12 hours and long-acting bronchodilators for 48 hours prior to pulmonary function testing.

Bronchial responsiveness to methacholine

The subjects were asked to refrain from consuming caffeine-containing beverages and from using bronchodilator and anti-inflammatory drugs for a minimum of 48 hours before testing. The subjects were seated wearing a nose clip and were instructed to take a slow vital capacity inhalation through the mouthpiece attached to the spirometer. The nebulizer (Pulmo-Aide; DeVilbiss Heathcare Inc., Somerset, PA, USA) was powered by an electric compressor.

Normal saline solution was inhaled first, followed by doubling concentrations of methacholine (0.625–25 mg/mL) at 5-minute intervals. The FEV1 was measured before and 30, 90, and 180 seconds after each inhalation. The inhalation was discontinued when the FEV1 fell 20% below the lowest postsaline solution value or when a dose of 25 mg/mL was reached. The results were expressed as the provocative concentration of methacholine resulting in a 20% fall in FEV1 (PC20) obtained from the log dose–response curve by linear interpolation. Subjects with a PC20 <25 mg/mL were considered to have airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR).Citation20

Skin-prick tests

Atopic status was measured by skin-prick tests using 13 common aeroallergens applied to the forearm. The allergens tested (HAL Allergen Lab B.V., Haarlem, the Netherlands) were house dust mites (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Dermatophagoides farinae), household pets (cat and dog), pollens (mixed grass, olive, mixed weed, and Parietaria judaica) and molds (Alternaria and Aspergillus fumigatus). Histamine and glycerinated saline solution were used as positive and negative controls. A skin-prick test result was considered positive if the mean wheal diameter was at least 3 mm.

Sputum induction and processing

Sputum was induced by inhalation of hypertonic saline aerosol and processed as described previously.Citation21 Briefly, 15 minutes after salbutamol inhalation (200 μg), normal saline 0.9% and then hypertonic saline (3%, 4%, and 5%) nebulized by an ultrasonic nebulizer (UltraNeb 2000; DeVilbiss Heathcare Inc.) were inhaled for each concentration over a period of 7 minutes. Subjects were encouraged to cough deeply after the 7-minute intervals. All subjects produced an adequate aliquot of sputum that was processed within 2 hours after termination of the induction.

For differential cell counting, we counted 400–500 non-squamous cells and reported the percentage of eosinophils, neutrophils, macrophages, lymphocytes, and bronchial epithelial cells present in the total nonsquamous cell count. Sputum samples containing >20% of squamous cells and with cell viability <70% were excluded from analysis as indication of poor quality.

Sputum supernatants were stored at −80°C for subsequent assay for interleukin (IL)-4, IL-8, IL-13, TNF-α, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) concentration.Citation22

Bronchoscopy

After local anesthesia of the throat, larynx, and bronchi, which was achieved with 2% lidocaine, a flexible bronchoscope (BF-1T200; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was introduced into the bronchial tree and gently wedged into the segmental bronchi of the right middle lobe. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was obtained by instillation and withdrawal of a total amount of 100 mL normal saline through the working channel. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was considered technically acceptable if >40% of the total normal saline instilled was recovered, and the lavage fluid (except for the first sample) contained few epithelial cells. To optimize cell viability, BALF was kept at 4°C until analyzed. The number of cells per milliliter in the recovered BALF was counted with a cytometer on whole BALF specimens stained with trypan blue and also with May–Grünwald for the evaluation of differential cell counts.Citation23

Measurement of inflammation biomarkers

IL-8, IL-4, IL-13, TNF-α, VEGF, and ECP concentrations were measured in both serum and sputum supernatants.

The concentrations of TNF-α, IL-8, IL-13, and IL-4 were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using kits purchased from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, USA). The sensitivities of the assays used were 1.6, 3.5, 32, 9, and 10 pg/mL, respectively. ECP was measured using UniCAP ECP kit (Pharmacia Diagnostics, Uppsala, Sweden) with a detection limit of 0.5 ng/mL.

In all cases, the assays were carried out according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD, and categorical variables are expressed as relative frequencies and percentages. Differences in markers of inflammation between time points in the studied group were initially assessed by the Kruskal–Wallis test and if significant by the Mann–Whitney rank test. Correlations between inflammatory cells and cytokines in sputum, smoking characteristics, or lung function parameters were calculated with Spearman’s rank correlation test. Statistical analysis was not influenced by values at the lower limits of detection since the nonparametric tests used were based on ranks of values. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 60 firefighters of mean age 32.4±5.7 (mean ± SD) were included in the study. In all, 52 (87%) of them were current smokers with a smoking history of 9±5 pack-years (mean ± SD). The mean duration of occupation was 8±6 years (mean ± SD). None of these firefighters was previously diagnosed with asthma, and 1 (2%) had a previous diagnosis of allergic rhinitis. In all, 23 among 60 (38%) firefighters were atopic (had at least one skin-prick test positive to one of the tested antigens). None of the participants were diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchiectasis, or any other chronic condition of the lung.

Respiratory symptoms such as wheezing, cough, chest tightness, sneezing, and expectoration were statistically significantly higher after firefighting as compared to off-season status (p=0.028, p=0.03, p=0.02, p<0.001, and p=0.006, respectively; ).

Table 1 Respiratory symptoms off-season and post exposure

Pulmonary function tests and bronchial hyperresponsiveness

Pulmonary function and bronchial hyperreactivity off-season and after firefighting are shown in . Post exposure, there were no significant differences in FEV1% predicted and FVC% predicted as compared to off-season. However, FEF25–75% predicted and FEV1/FVC were statistically significantly reduced post exposure compared to off-season values (103±32 vs 111±15 [mean ± standard error {SE}], p=0.026, and 84±4 vs 88±8 [mean ± SE], p=0.024, respectively; ). Moreover, a statistically significant increase in total lung capacity (TLC% predicted; 90±11 vs 97±11 [mean ± SE], p=0,029), along with statistically significant reduced diffusing lung capacity (KCO% predicted; 107±14 vs 99±13 [mean ± SE], p=0,039), was observed post exposure ().

Table 2 Pulmonary function test and bronchial hyperresponsiveness off-season and post exposure

No significant difference was observed between the rate of positive bronchial provocation tests off-season and post exposure (6 [13%] vs 8 [18%], p=0.568, respectively), as well as the provocative dose of methacholine producing a 20% fall in FEV1 ().

Markers of inflammation

The analysis of the sputum samples revealed a significant increase in neutrophils and eosinophils post exposure as compared to off-season (48±5% vs 16±4% [mean ± SE], p=0.035, and 3±0.8% vs 1.8±0.7% [mean ± SE], p=0.05, respectively; ). BAL analysis showed a significantly higher percentage of neutrophils post exposure as compared to off-season (4±1.2% vs 2±0.3% [mean ± SE], p=0.043; ). There were no significant differences in the rest of the cell types assessed off-season and post exposure ().

Table 3 Total and differential cell counts in sputum and BALF

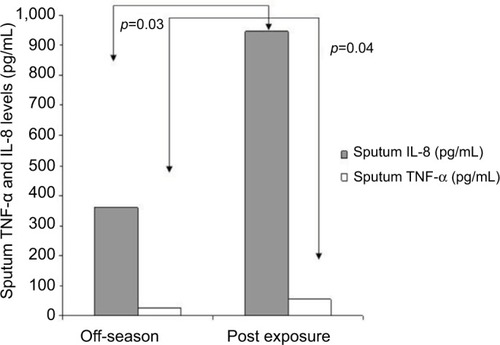

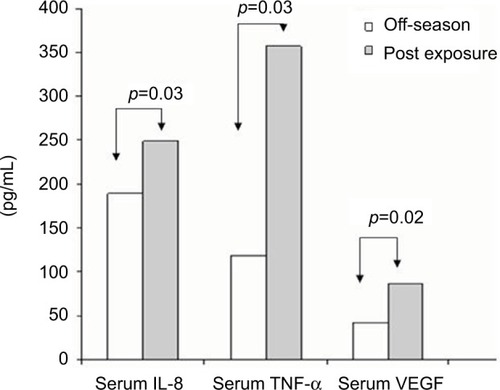

IL-8 and TNF-α levels were found to be statistically significantly higher in the sputum supernatants post exposure as compared to the off-season (p=0.03 and p=0.04, respectively; ). Furthermore, serum IL-8, VEGF, and TNF-α levels were statistically significantly higher post exposure as compared to off-season (p=0.03, p=0.02, and p=0.03, respectively; ). There were no differences in the degree of inflammation induced post exposure or off-season between smoking and nonsmoking firefighters (). We postulate that the reason for these results, especially for off-season, may be explained by the small number of smokers (eight people) and the rather low number of smoking pack-years.

Table 4 Markers of inflammation in induced sputum and serum

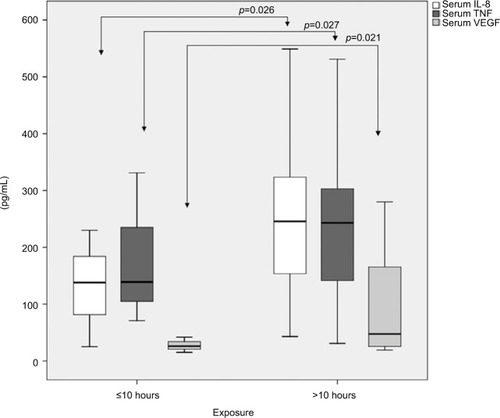

In firefighters who participated in the operations of forest firefighting continuously for >10 hours (38±22 hours [mean ± SD]), the exposure induced a more intense systemic inflammation compared to an exposure of <10 hours (6±3 hours [mean ± SD]; ).

Discussion

In the current study on forest firefighters, a measurable eosinophilic and neutrophilic inflammation was shown to be induced in the bronchial airways after acute exposure in forest firefighting. This was associated with respiratory symptoms from the upper and lower respiratory tract and pulmonary function impairment. Additionally, a measurable systemic inflammatory response was demonstrated.

After the World Trade Center incident, a number of studies assessed the effects of occupational exposure on respiratory symptoms and pulmonary function in professional firefighters.Citation3,Citation9,Citation17,Citation18,Citation24 However, most of these studies examined the long-term consequences of inhalation of particulate matter and irritant gases on pulmonary function and airway and systemic inflammation.

The most striking finding of our study is the significantly higher percentage of eosinophils post exposure compared to off-season in the sputum and BAL of firefighters. Firefighters are exposed to numerous irritants during the operations, and such an exposure alters lung permeability easing the penetration and accessibility of inhaled allergens, leading eventually to an allergic immune response.Citation25,Citation26 Allergic airway sensitization has been previously reported among firefighters on the basis of the presence of atopy and symptoms from the upper and lower respiratory systems.Citation4,Citation5,Citation9,Citation13 We recently documented allergic sensitization in professional firefighters after chronic occupational exposure.Citation13 Furthermore, eosinophilia has been shown in the induced sputum of sensitized asthmatics and in asbestos workersCitation27 after chronic occupational exposure. In the current study, we demonstrated an induction of the allergic immune response in the airways after firefighting. Combined with our and others’ previous findings on the effects of chronic exposure on the airways, we would be justified to suggest that repetitive exposure to combustion products in combination with allergens may lead to the allergic sensitization seen in professional firefighters after long-term exposure.Citation4,Citation12,Citation13,Citation28 Indeed, a high risk for asthma and allergic rhinosinusitis is reported among professional firefighters in numerous studiesCitation29–Citation32 A significantly higher allergen-specific IgE induction compared to the challenge with the allergen alone has been previously demonstrated in the work of Dong et alCitation33 who demonstrated that exposure to diesel exhaust particles prior to ovalbumin sensitization in rats exacerbates the allergic responses to the subsequent challenge with OVA in OVA-sensitized rats. Furthermore, increased sensitization to outdoor allergensCitation34,Citation35 has been documented in people living in areas with high traffic.

It is well established that occupational exposure in firefighters leads to chronic airway and systemic inflammation, and we have recently demonstrated that this is evident even from the first year in occupation, becoming more intense as the exposure years increase.Citation7,Citation13–Citation16 In this study, it was further shown that acute exposure during forest firefighting significantly augments the intensity of airway and systemic inflammation compared to the baseline inflammatory background. A markedly higher degree of airway inflammation was documented post exposure compared to off-season as reflected by the higher number of total cells and the elevated counts of neutrophils in sputum and BAL. This is in line with the results of studies examining the acute effect of inhalation of particulate matter or diesel exhaust showing increased neutrophil counts in BAL and induced sputum following exposure.Citation15,Citation36–Citation38 Specifically, Greven et alCitation15 showed that acute exposure to fire smoke induces acute neutrophilic airway and long-lasting systemic inflammation in healthy firefighters, and this was also shown in our recent work on professional firefighters.Citation13 Additionally, significantly higher levels of IL-8 and TNF-α were found in induced sputum post exposure. Holgate et alCitation39 demonstrated that modest concentrations of diesel exhaust have clear-cut inflammatory effects on the airways of non-asthmatic subjects, suggesting a direct effect of diesel exhaust on IL-8 production, leading to upregulation of endothelial adhesion molecules and neutrophil recruitment. In this study, we documented that acute exposure further enhances that long-lasting systemic inflammation, and this effect is time dependent. There were no differences in the degree of inflammation induced post exposure or off-season between smoking and nonsmoking firefighters. We postulate that the reason for these results, especially for off-season, may be explained by the small number of smokers (eight people) and the rather low number of smoking pack-years.

Serum IL-8, VEGF, and TNF-α concentrations were found to be significantly higher post exposure compared to off-season. The elevated levels of circulating cytokines following smoke exposure are consistent with the findings of previous studies indicating the stimulation of the bone marrowCitation40–Citation42 and the initiation of a systemic inflammatory response as a result of smoke inhalation. IL-8 is a potent stimulator of bone marrow promoting the sequestration of neutrophils in the lung.Citation43 This possibly enhances or perpetuates the neutrophilic inflammation seen in the bronchi and initiates the systemic inflammatory response as a result of smoke inhalation.

Exposure to products of pyrolysis has been shown to increase airway responsiveness in some subjects.Citation4,Citation10,Citation11,Citation18,Citation44 Although we observed no increase in bronchial hyperreactivity, this may not be odd since bronchial hyperreactivity is defined by and dependent on multiple factors. In most studies, bronchial hyperreactivity after smoke inhalation seems to be related to a prior long history of firefighting activity, the number of fires fought in 12 months, the atopic condition, and the respiratory protection devices used.Citation3 In the relatively small sample studied here, the diversities between the subjects may justify the lack of bronchial hyperreactivity seen post exposure.

Our results are in agreement with previous studies showing deterioration in pulmonary function after exposure.Citation6–Citation8,Citation44 We specifically found a larger decrease in FEF25–75, a measure of smaller airway dysfunction, suggesting that acute exposure to smoke during firefighting mainly affects peripheral lung. This finding agrees with the early findings of Large et alCitation7 who showed a significant decrease in spirometric values right after exposure, Greven et alCitation44 who showed a significant decrease in spirometric values right after exposure and 24 hours later, Slaughter et alCitation6 who showed a greater decrease in FEF25–75 post shift compared to pre shift, and Liu et alCitation45 who compared cross-season effects of forest fire smoke on lung function. Symptoms from both the upper and the lower respiratory tract included chest tightness, wheezing, cough, increased sputum production, and sneezing, and they were more pronounced after exposure to smoke compared to off-season. Previous studies observed a significant increase in eye irritation, nose irritation, cough, phlegm, and wheezing from preseason to late season, with strong associations noted for recent firefighting activity.Citation5,Citation30

Conclusion

This study showed that each exposure to smoke and allergens during forest firefighting significantly augments the intensity of airway and systemic inflammation in relation to the baseline inflammatory background due to chronic exposure. Interestingly, an eosinophilic immune response is induced in the airways, which is suggested to eventually lead to allergic airway sensitization and increased incidence of rhinitis and asthma after prolonged exposure. It seems that at every single exposure, an airway and systemic inflammatory spike is induced, eventually leading to the establishment of pathology. These findings underline the need for the SCBA use during firefighting.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the firefighters of the Hellenic Fireforce Department for their participation in this study and the nurses L. Stoubi and F. Zikopoulou for their valuable assistance and support in the endoscopic laboratory. The study was supported by “Thorax” Foundation and funded by Chiesi Hellas.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ReinhardtTEOttmarRDBaseline measurements of smoke exposure among wildland firefightersJ Occup Environ Hyg20041959360615559331

- BaxterCSHoffmanJDKnippMJReponenTHaynesENExposure of firefighters to particulates and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbonsJ Occup Environ Hyg2014117D85D9124512044

- FeldmanDMBaronSLBernardBPSymptoms, respirator use, and pulmonary function changes among New York City firefighters responding to the World Trade Center disasterChest200412541256126415078732

- MiedingerDChhajedPNStolzDRespiratory symptoms, atopy and bronchial hyperreactivity in professional firefightersEur Respir J200730353854417537776

- GaughanDMCox-GanserJMEnrightPLAcute upper and lower respiratory effects in wildland firefightersJ Occup Environ Med20085091019102818784550

- SlaughterJCKoenigJQReinhardtTEAssociation between lung function and exposure to smoke among firefighters at prescribed burnsJ Occup Environ Hyg200411454915202156

- LargeAAOwensGRHoffmanLAThe short-term effects of smoke exposure on the pulmonary function of firefightersChest19909748068092323250

- JacquinLMicheletPBrocqFXShort-term spirometric changes in wildland firefightersAm J Ind Med2011541181982522006591

- PrezantDJWeidenMBanauchGICough and bronchial responsiveness in firefighters at the World Trade Center siteN Engl J Med20023471180681512226151

- ChiaKSJeyaratnamJChanTBLimTKAirway responsiveness of firefighters after smoke exposureBr J Ind Med19904785245272393631

- ShermanCBBarnhartSMillerMFFirefighting acutely increases airway responsivenessAm Rev Respir Dis198914011851902665585

- WylerCBraun-FahrländerCKünzliNExposure to motor vehicle traffic and allergic sensitization. The Swiss Study on Air Pollution and Lung Diseases in Adults (SAPALDIA) TeamEpidemiology200011445045610874554

- GianniouNKatsaounouPDimaEProlonged occupational exposure leads to allergic airway sensitization and chronic airway and systemic inflammation in professional firefightersRespir Med201611871427578465

- SwistonJRDavidsonWAttridgeSLiGTBrauerMvan EedenSFWood smoke exposure induces a pulmonary and systemic inflammatory response in firefightersEur Respir J200832112913818256060

- GrevenFEKropEJSpithovenJJAcute respiratory effects in firefightersAm J Ind Med2012551546221959832

- HejlAMAdetonaODiaz-SanchezDInflammatory effects of woodsmoke exposure among wildland firefighters working at prescribed burns at the Savannah River Site, SCJ Occup Environ Hyg201310417318023363434

- BanauchGIHallCWeidenMPulmonary function after exposure to the World Trade Center collapse in the New York City Fire DepartmentAm J Respir Crit Care Med2006174331231916645172

- BanauchGIAlleyneDSanchezRPersistent hyperreactivity and reactive airway dysfunction in firefighters at the World Trade CenterAm J Respir Crit Care Med20031681546212615613

- American Thoracic SocietyStandardization of spirometry, 1994 updateAm J Respir Crit Care Med19951521107e367663792

- CrapoROCasaburiRCoatesALGuidelines for methacholine and exercise challenge testing-1999. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999Am J Respir Crit Care Med2000161130932910619836

- RovinaNDimaEGerassimouCKollintzaAGratziouCRoussosCIL-18 in induced sputum and airway hyperresponsiveness in mild asthmatics: effect of smokingRespir Med2009103121919192519539457

- KipsJCFahyJVHargreaveFEMethods for sputum induction and analysis of induced sputum: a method for assessing airway inflammation in asthmaEur Respir J Suppl1998269e12S

- BaughmanRPTechnical aspects of bronchoalveolar lavage: recommendations for a standard procedureSemin Respir Crit Care Med200728547548517975775

- HerbertRMolineJSklootGThe World Trade Center disaster and the health of workers: five-year assessment of a unique medical screening programEnviron Health Perspect2006114121853185817185275

- D’AmatoGLiccardiGD’AmatoMHolgateSEnvironmental risk factors and allergic bronchial asthmaClin Exp Allergy2005351113112416164436

- DevaliaJLRusznakCDaviesRJAllergen/irritant interaction – its role in sensitization and allergic diseaseAllergy1998533353459574874

- MaestrelliPCalcagniPGSaettaMSputum eosinophilia after asthmatic responses induced by isocyanates in sensitized subjectsClin Exp Allergy199424129348156442

- Diaz-SanchezDPenichet-GarciaMSaxonADiesel exhaust particles directly induce activated mast cells to degranulate and increase histamine levels and symptom severityJ Allergy Clin Immunol200010661140114611112898

- NilesJKWebberMPLiuXThe upper respiratory pyramid: early factors and later treatment utilization in World Trade Center exposed firefightersAm J Ind Med201457885786524898816

- NilesJKWebberMPCohenHWThe respiratory pyramid: From symptoms to disease in World Trade Center exposed firefightersAm J Ind Med201356887088023788055

- RibeiroMde Paula SantosUBussacosMATerra-FilhoMPrevalence and risk of asthma symptoms among firefighters in São Paulo, Brazil: a population-based studyAm J Ind Med200952326126919117017

- WeakleyJWebberMPGustaveJTrends in respiratory diagnoses and symptoms of firefighters exposed to the World Trade Center disaster: 2005-2010Prev Med201153636436921930151

- DongCCYinXJMaJYEffect of diesel exhaust particles on allergic reactions and airway responsiveness in ovalbumin-sensitized brown Norway ratsToxicol Sci200588120221216107553

- GruzievaOBellanderTEnerothKTraffic-related air pollution and development of allergic sensitization in children during the first 8 years of lifeJ Allergy Clin Immunol2012129124024622104609

- BernsteinDITraffic-related pollutants and wheezing in childrenJ Asthma20124915722211400

- SalviSSNordenhallCBlombergAAcute exposure to diesel exhaust increases IL-8 and GRO-alpha production in healthy human airwaysAm J Respir Crit Care Med20001612 Pt 155055710673199

- FujiiTHayashiSHoggJCVincentRVan EedenSFParticulate matter induces cytokine expression in human bronchial epithelial cellsAm J Respir Cell Mol Biol200125326527111588002

- IshiiHHayashiSHoggJCAlveolar macrophage-epithelial cell interaction following exposure to atmospheric particles induces the release of mediators involved in monocyte mobilization and recruitmentRespir Res200568716053532

- HolgateSTSandströmTFrewAJHealth effects of acute exposure to air pollution. Part I: healthy and asthmatic subjects exposed to diesel exhaustRes Rep Health Eff Inst2003112130 discussion 51–67

- TanWCQiuDLiamBLThe human bone marrow response to acute air pollution caused by forest firesAm J Respir Crit Care Med20001614 pt 11213121710764314

- GotoYIshiiHHoggJCParticulate matter air pollution stimulates monocyte release from the bone marrowAm J Respir Crit Care Med2004170889189715256391

- TerashimaTWiggsBEnglishDHoggJCvan EedenSFPhagocytosis of small carbon particles (PM10) by alveolar macrophages stimulates the release of polymorphonuclear leukocytes from bone marrowAm J Respir Crit Care Med19971554144114479105091

- TerashimaTEnglishDHoggJCvan EedenSFRelease of polymorphonuclear leukocytes from the bone marrow by interleukin-8Blood1998923106210699680376

- GrevenFKropESpithovenJRooyackersJKerstjensHHeederikDLung function, bronchial hyperresponsiveness, and atopy among firefightersScand J Work Environ Health201137432533121340442

- LiuDTagerIBBalmesJRHarrisonRJThe effect of smoke inhalation on lung function and airway responsiveness in wildland fire fightersAm Rev Respir Dis19921466146914731456562