Abstract

Food allergy is an immune-mediated disease that can result in considerable morbidity and even mortality, with a significant negative impact on patients’ quality of life. It is characterized by allergic symptoms that can occur shortly after a relevant food allergen ingestion, or can be delayed or chronic, which make it more difficult for diagnosis. The symptoms of this disease can range from mild to severe, and rarely can cause anaphylaxis, a life-threatening allergic reaction. The prevalence of non-immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated food allergy is poorly established outside of cow’s milk allergy, with an adjusted incidence ranging between 0.13% and 0.72%. Several disorders are classified as non-immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated food allergies that predominantly affect the gastrointestinal tract including food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES), food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis (FPIAP), food protein-induced allergic enteropathy (FPE), and food protein-induced dysmotility disorders (GORD and constipation). Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is listed in this group, even though it considered by some authorities to be mixed reaction with both IgE and cell-mediated immune response to be involved in the reaction. The most common types of non-IgE-mediated food allergy are food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES) and food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis (FPIAP). These disorders typically present in infancy and are often triggered by cow's milk protein. Patients with FPIES present with profuse emesis and dehydration, while FPIAP patients present with hematochezia in otherwise healthy infants. Since there are no specific confirmatory non-invasive diagnostic laboratory tests, the diagnosis is usually made clinically when typical symptoms improve upon the removal of the culprit food. Food reintroduction should be attempted, when possible, with documentation of symptoms of relapse to confirm the diagnosis. The management includes dietary avoidance, supportive treatment in the case of accidental exposure, and nutritional counseling. This review focuses on the clinical manifestations, epidemiology, management, and recent guidelines of the most common non-IgE-mediated food hypersensitivity disorders (FPIES, FPIAP, and FPE).

Introduction

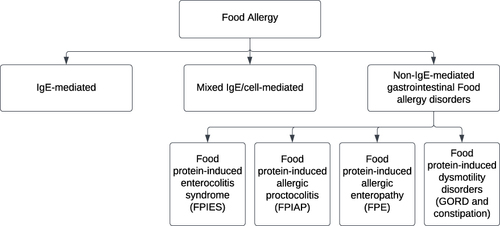

Food allergy (FA) is characterized by an immune reaction to a particular food that can be triggered repeatedly. It can be categorized by pathophysiology into immunoglobulin E-mediated, non-IgE- mediated, or mixed IgE disorders (). IgE-mediated reactions are the majority when it comes to food allergies; however, newborns and young children can suffer from non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergies. Presentation is often in infants with non-specific symptoms and signs, and because of lack of non-invasive reliable tests, diagnosis and treatment can be challenging.Citation1,Citation2

Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergic disorders (non-IgE-GI-FA) are thought to be cell-mediated since they typically manifest many hours after eating the offending food and are accompanied by negative skin prick tests and absence of serum-specific IgE against the offending food.Citation1,Citation3 These diseases are thought to be mediated by T helper cells and other activated lymphocyte populations, including cytotoxic CD8 T cells, unlike the classical pathogenesis of IgE-mediated food allergy.Citation4–6 Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergic disorders include food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES), food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis (FPIAP), and food protein-induced enteropathy (FPE).Citation4,Citation7

The diagnosis of non-IgE-mediated food allergy is typically based on the history of reproducible symptoms and signs following exposure to the offending food, due to the lack of specific biomarkers and non-invasive diagnostic tests. The mainstay of treatment is food avoidance and symptomatic treatment depending on the associated symptoms including vomiting and diarrhea that could lead to dehydration, lethargy, and hypotension.Citation3,Citation8 In addition to the disease symptoms, parents of children with non-IgE FA disease often report lower quality of life and more challenges with feeding compared to those of children with IgE-mediated food allergy.Citation9,Citation10

Epidemiology

The prevalence and epidemiological features of non-IgE-mediated food allergies have not been well studied. However, available prevalence data suggest that these conditions are less common than IgE-mediated food allergies.Citation11

There has been a recent interest in non-IgE-GI-FA knowledge and awareness around the world with FPIAP being the most frequent. A recent prospective study of 903 healthy infants found that, FPIAP incidence was 17% over 3 years, with the diagnosis being made by pediatrician caring for the infant; however, the diagnosis was not confirmed by re-introducing suspected food shortly after symptom resolution, as recommended.Citation12 During the first 2 months of life, infants who were fed a combination of breast milk and cow’s milk-based formula or only breast milk had a lower risk of developing FPIAP compared to infants who were fed only formula, 61% and 53%, respectively.Citation12

The cumulative incidence of FPIES in infants is predicted to be between 0.015% and 0.7%, although the population prevalence in infants in the United States is 0.51%.Citation13 The incidence of FPIES was reported to be 0.015% in Australian newborns, with rice being the most common food trigger.Citation14 However, a higher incidence 0.34% over a follow-up period of 2 years and 0.7% with an at least 18 months’ follow-up has been reported.Citation15,Citation16 According to a review of the epidemiology of FPIES, at the time of diagnosis, eczema and a family history of atopy are common, and with a slight male predominance.Citation17 FPIES is commonly diagnosed in infants. However, new-onset adult FPIES has been reported.Citation18 Nowak-Wegrzyn et al reported the first estimated prevalence of adult FPIES in the USA which was 0.22%.Citation19 Furthermore, González-Delgado et al reported the clinical characteristics of adult patients with FPIES where abdominal pain was the most common manifestation followed by diarrhea.Citation20

FPE is relatively uncommon, affecting approximately a fifth of celiac patients, and it appears to be decreasing over time.Citation21 Over the past few decades, FPE incidence has generally decreased after its peak in Finland, in the 1960s, and instances brought on by cow’s milk gradually disappeared after that.Citation21

Food allergy has been reported to be higher in children with Down syndrome than seen in children without mental retardation.Citation22 Moreover, non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergy have been reported in children diagnosed with Down syndrome which is characterized by a severe long-lasting course.Citation23–25

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

FPIAP, FPIES, FPE

Diagnosing the cause of a child’s gastrointestinal symptoms can be challenging due to the wide variety of symptoms and overlapping of the clinical features.Citation1 In addition, due to the lack of widely available, noninvasive confirmatory tests for most of non-IgE-mediated food hypersensitivity syndromes, accurate diagnosis of these disorders can be challenging.Citation2

The diagnosis of non-IgE-GI-FA is based on the recognition of the symptoms pattern; therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to the history of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms that vary with respect to their temporal relationship to food ingestion, severity, and natural history in order to differentiate between various causes. GI symptoms are usually subacute or chronic symptoms and delayed after exposure to foods with age of onset at 2–8 weeks of age and as early as first week.Citation26,Citation27 Non-IgE-mediated food allergies typically manifest in the digestive tract, but can also manifest in other organ systems like the skin including contact dermatitis to foods and dermatitis herpetiformis and lungs including pulmonary hemosiderosis.Citation2,Citation28 Symptoms could range from intermittent but progressive emesis that could lead to dehydration, diarrhea with or without blood, to failure to thrive (FTT) and nutritional deficiencies in severe cases.Citation2,Citation27,Citation28

FPIAP represents the milder end of the spectrum; it is one of the most frequent causes of colitis in infants under 1 year of age and has a benign, transitory course.Citation4,Citation29 It is characterized by intermittent moderate bloody stools that present as streaks of blood mixed with mucus in generally healthy infants with no effect on the growth and resolves by age 12 months in most of the cases.Citation4,Citation27,Citation30 The immune response occurs in most of the times in breastfed infants due to reaction to cow’s milk allergy, soy, egg or wheat in maternal diet. Infant formulas containing cow’s milk or soy can cause similar reaction.Citation31–33 Symptoms usually improve within few days after removal of the offending protein from maternal diet. However, complete resolution may be achieved after 2 weeks.Citation31 Although FPIAP has been thought to be a disease of infancy, it has been reported among older children; Ravelli et al in their case series, they described 16 patients aged 2–14 years who presented with a rectal bleeding that resolved with cow's milk protein elimination.Citation34 Furthermore, histologic findings of their endoscopic biopsies were consistent with FPIAP.Citation34 Odze et al reported that having 60 eosinophils/10 high-power fields in the lamina propria is enough to make the diagnosis in the vast majority of cases, even though the histopathological findings are not pathognomonic of the disease.Citation26

FPIES is a severe form of non-IgE-mediated disorder that typically affects young infants and manifests as chronic emesis, diarrhea and failure to thrive with recurrent vomiting and dehydration upon re-exposure to the offending food.Citation4,Citation27 Chronic FPIES develops if the food antigen is regularly taken, and it has been reported in infants with cow's milk and soya-based formula.Citation28 On the other hand, FPIES can has an acute manifestation as copious, repeated, projectile vomiting that begins 1–4 hours after eating the food and may accompany watery diarrhea that develops 5–8 hours later and may cause pallor, lethargy, dehydration, and/or hypovolemic shock.Citation28,Citation35 The acute presentation of FPIES can mimic gastroenteritis, intussusception, sepsis, metabolic crisis, or even necrotizing enterocolitis.Citation36 The delayed diagnosis of FPIES due, perhaps, to little-to-lack of knowledge of pediatricians as shown in a survey done by Schultz and Westcott-ChavezCitation37 may lead to unnecessary medical investigations and frequent prescriptions of antibiotics compared to allergy-free infants.Citation38 Natural history of FPIES varies greatly depending on the study population, causal foods, and associated atopic disorders; nonetheless, the majority of children will outgrow FPIES by the age of 3 or 4.Citation39 Food triggers vary depending on the geographical origin, for example, the most frequent food triggers for infants in the US are cow’s milk and soy, and as infants are introduced to solid foods, reactions to grains (rice, oat) become increasingly common.Citation35 However, in a recently published report from the east Mediterranean region, hen’s egg (36.6%) was the most prevalent culprit food followed by fish (26.9%) and then cow's milk (21.5%).Citation40 An oral food challenge is the gold standard for diagnosis in cases of chronic FPIES and for which there is no clear history and no clear temporal link between symptoms and specific food intake.Citation41 However, it is not necessary for diagnosis in infants with typical characteristic signs and symptoms that improvement after elimination of the suspected trigger food. Although FPIES has been thought of as a disease that affects children, recent studies suggest that FPIES might develop in older individuals.Citation11 Tan and Smith have reported 31 cases of acute onset of vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain triggered by a specific food in patients older than 18 years.Citation42 Symptoms appeared 1–2 hours after food ingestion, lasted 1–3 hours and experienced on a median of two occasions with the suspected food.Citation42

Patients with FPE or cow’s milk-sensitive enteropathy usually depend on age of exposure to antigen. They usually complain of chronic diarrhea and malabsorption with steatorrhea, weight loss and failure to thrive that emerge soon after infants are exposed to cow’s milk in the diet and improve when cow’s milk is discontinued from the diet.Citation2,Citation11,Citation21,Citation28,Citation43 A close resemblance can be seen between these signs and those of celiac disease and post-enteritis syndrome.Citation2,Citation43,Citation44 A major difference between FPIAP patients and FPIES patients with acute symptoms, who usually do not need a biopsy, histologic confirmation of FPE necessitates a biopsy.Citation28 Eliminating the offending food causes symptoms to subside within 1–4 weeks, while the patchy villous atrophy continues months after there is apparent clinical improvement.Citation21

Apart from the GI symptoms, non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergy is at risk of vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency.Citation45 In addition, it has been reported that it causes psychological distress not only to the child but also the parent QOL and family functioning was also observed to be worse in those families who had a child on an elimination diet for non-IgE-mediated allergies ().Citation46

Investigations and Biomarkers ()

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory tests can be helpful in supporting the diagnosis of non-IgE-GI-FA. In FPIES, blood testing may reveal anemia, thrombocytosis, high white blood cell count with left shift and hypoalbuminemia.Citation41 Patients with severe disease might develop metabolic acidosis and high levels of methemoglobin protein.Citation47 A promising diagnostic marker called thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC) has been recently used.Citation48,Citation49 It is a Th2 chemokine that is produced by fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and keratinocytes.Citation49,Citation50 Although TARC is used to assess patients with atopic dermatitis, patients with symptoms of FPIES found to have an elevated level.Citation49,Citation50 Makita et al have performed a longitudinal evaluation of TARC levels on FPIES patients which revealed a high level at 6 hours following the ingestion, and even higher level after 24 hours of the ingestion.Citation50 Therefore, they recommended TARC measurement after 24 hours for diagnosing FPIES.Citation50 In FPE, patients often develop iron deficiency anemia and hypoproteinemia,Citation51 which present in less than 15% of the patients with FPIAP.Citation32,Citation52 Peripheral eosinophilia is a prominent feature in FPE and FPIAP and can be found in patients with FPIES.Citation52,Citation53

Table 1 Non-IgE-Mediated Allergic Disorders, Symptoms, and Differential Diagnoses (Taken from the European Academy for Allergy and Clinical Immunology Position Paper on the Management of Non-IgE-Mediated Allergies in Breastfed Infants)

Table 2 Key Investigation Findings of FPIAP, FPIES, and FPE

Stool Studies

Stool studies results including eosinophils, neutrophils, reducing substances, and Charcot–Leyden crystals can be nonspecific in patients with FPIES.Citation41 Other stool testing such as occult blood was used to help in diagnosing FPIES but found to be non-specific as it can present in other diseases such as FPIAP.Citation12 Fecal calprotectin which indicates inflammation of the gut mucosa can be elevated in patients with FPIAP and FPIES.Citation54,Citation55 However, data are scarce, and unavailability of validated normal ranges for infants makes its utility in diagnosing these conditions limited.Citation56 Therefore, the routine use of stool tests is not recommended.Citation56

Endoscopic Evaluation and Biopsy

This test is used to support the diagnosis of FPE. Histology findings include jejunal villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia and inflammation. These findings tend to be less severe than those seen in celiac disease.Citation57,Citation58 Biopsy is not indicated in FPIES and FPIAP unless there is uncertainty in the diagnosis. However, biopsies were taken from patients with FPIAP shown eosinophilic infiltration in the lamina propria and epithelium.Citation2 Furthermore, multiple biopsies might be necessary because FPIAP is often a patchy disease.Citation59

Allergy Testing

This includes skin prick testing and the detection of serum food-specific IgE, which are usually negative. These tests are not requested for patients with non-IgE-mediated food allergy, unless there are associated severe atopic dermatitis or immediate allergic reaction to ingested food.Citation3,Citation43 However, approximately 25–30% of the patients with FPIES can have atypical FPIES and might develop IgE to the food trigger.Citation2,Citation43,Citation60 Hence, these patients are under risk of developing significant allergic reaction to the culprit food; therefore, allergy testing may be considered prior to OFC to exclude atypical FPIES.Citation43,Citation61 Recent studies suggest higher rate of atypical FPIES than previously reported rates; in the USA, it has been found to be 24% of 160 patientsCitation27 and 33% of 52 patients in the UK.Citation62

Oral Food Challenge Tests (OFC)

The OFC is considered the gold standard to diagnose FPIES, FPIAP, and FPE after symptoms resolution under dietary elimination. In addition, it is performed to assess the development of tolerance to the culprit food.Citation2,Citation27 In FPIES, OFC should be supervised by a physician in an appropriately monitored situation because of potential severe reactions occurrence and need for intervention. While in FPIAP and FPE, reintroduction of trigger food 4–8 weeks after elimination can safely be performed at home.Citation2

Management

Elimination Diet

The mainstay of the management of non-IgE-mediated food allergy is the removal of offending foods from the diet. Identification of triggers relies on clinical history. Cow’s milk is the most common trigger for FPIES, FPIAP, and FPE.Citation43 An oral food challenge is recommended when an infant’s history is unclear, such as the absence of a clear trigger, atypical symptoms, or lack of resolution with trigger food elimination.Citation63 The most common approach is to avoid causal foods without broad restrictions. Avoiding a wider variety of foods may be considered in severe cases of FPIES, when failure to thrive, and dehydration are present. For such cases, it is recommended to begin with an elemental diet, then be sequentially introduced to new foods while being closely monitored for the recurrence of symptoms.Citation43 It is usually unnecessary to avoid products with precautionary labeling (eg, “can contain traces of”).Citation41 While most children with IgE-mediated allergies tolerate baked products, there is limited data to support tolerance to baked food in patients with FPIES.Citation28 In a multicenter, retrospective research included 61 children with egg FPIES, the average time to achieve tolerance to cooked egg was reported to be 30.2 months, and 43.9 months for raw eggs.Citation64 While guidelines suggest strict avoidance of triggers, some patients have tolerated baked products. Tolerance is preferably established under a physician’s supervision.Citation28 Breastfeeding is recommended in FPIES and routine maternal dietary elimination of triggers is not recommended; unless if an allergic reaction occurs after breastfeeding, or/and exclusively breastfed infants are failing to thrive.Citation65 In cow’s milk/soy-induced FPIES, extensively hydrolyzed (eHF) or amino acid-based formulas (AAF) have been recommended.Citation65,Citation66 As cross-reactivity between cow’s milk and soy-based formulas is low, such that soy-based formula can be considered as an alternative for feeding infants with cow’s milk allergy and FPIES who are over 6 months of age.Citation15 As more infants with non-IgE-mediated than IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy react to eHF, which is likely due to residual cow’s milk protein; it was suggested by many experts that hydrolyzed rice formulas can be recommended as a first-line alternative to cow’s milk-based eHF or AAF, where available, in the dietary management of infants with cow’s milk allergy.Citation67 When a diagnostic elimination diet is indicated, hydrolyzed rice formula can be used.Citation67

Most exclusively breastfed infants with FPIAP respond to the maternal elimination of milk products. Cow’s milk elimination does not typically resolve FPIAP caused by other triggers, such as eggs, which can be removed from the maternal diet.Citation63 The European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) recommends 2–4 weeks of maternal elimination diet, followed by an attempt to re-introduce food to confirm the diagnosis.Citation68 Clinical bleeding typically resolves within 1–2 weeks with the elimination of the offending item from the mother’s diet. Most cases resolve within 72–96 hours; however, if symptoms prolong for at least 2 weeks, it is necessary to check the mother’s adherence and, if necessary, eliminate soy and egg from the diet.Citation69 Occasional recurrence of bleeding is common in breastfed infants, most likely due to small intakes of triggering protein. If bleeding is infrequent, small in amount, and self-limited, then no further intervention is needed, and the mother can maintain the current level of dietary restriction.Citation69 Some have suggested a “watch-and-wait” approach for a month before starting an elimination diet.Citation70,Citation71 The infant and mother can continue a regular diet without elimination if asymptomatic. Twenty percent of the patients with FPIAP are thought to resolve without maternal dietary elimination spontaneously.Citation70,Citation71 In those with symptoms for over a month, hemoglobin levels should be assessed.Citation43 Some infants, about 12%, continue to have persistent bleeding with changes in the maternal diet.Citation69 Moreover, Lozinsky et al found that the majority of children with non-IgE-mediated allergy had improvement of symptoms within 4 weeks; however, data were mainly based on non-breastfed children.Citation72

When exclusive breastfeeding is not possible or failure of symptom resolution when dairy (±soy) is eliminated from the maternal diet, guidelines recommend extensively hydrolyzed formula (EHF) for mild cases and amino-acid-based formula (AAF) for severe cases. AAFs are recommended when symptoms do not resolve with EHF, failure to thrive, multiple food allergies, and eosinophilic esophagitis.Citation73,Citation74 The European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended avoiding soy-based formulas due to a high risk of co-reactivity with cow’s milk. In addition, there are concerns based on animal data regarding the phytoestrogen content in soy-based formula and the potential risk for infants, especially premature and infants with congenital hypothyroidism (CH).Citation75 Therefore, soy-based formula is not recommended before the age of 6 months in infants with cow's milk-induced FPIES who are premature or diagnosed with CH.Citation65 Soy formula can be used in infants older than 6 months if EHF is not tolerated, is too expensive, or guardian preferences (vegan diet).Citation76 It is recommended to re-introduce the offending food to the mother or infant’s diet after 6 months of elimination or at 12 months of age.Citation69 In cases of failure, the trigger should be removed, and new attempts can be made after 6 months.Citation43 There is currently insufficient evidence to recommend the routine use of formulas enriched with pre/pro/postbiotics and synbiotics in managing children with cow’s milk allergy.Citation77,Citation78

Most infants outgrow FPIAP by 1 year and can ingest food without restriction.Citation79 Infants with uncomplicated FPIAP may not require an allergy referral. However, further evaluation may be warranted if the trigger cannot be identified, or symptoms do not resolve with trigger elimination. Sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy with biopsies may be necessary for patients that require further evaluation. They are recommended for patients with atypical symptoms, severe rectal bleeding, or anemia despite a cow’s milk elimination diet trial.Citation69 FPIAP is a benign transient medical condition; however, in small percentage of patients, resolution of the allergy can be delayed up to age of 3 years.Citation52,Citation70 Therefore, an evaluation of late tolerance risk factors can help reduce the stress of long-term maternal dietary elimination.Citation52 Cetinkaya et al in their prospective study that included 185 infants with FPIAP, non-IgE-mediated multiple-food allergies, using cow's milk formula before the symptoms emerged, concomitant IgE-related food allergy, and delay in timing of complementary feeding were reported as predictors for late tolerance development.Citation18

Acute Management

FPIES

Management of acute FPIES reactions is based on the severity of symptoms. Oral rehydration and close monitoring for 4–6 hours at home are suggested for mild symptoms. For moderate-to-severe symptoms, emergency care or hospitalization may be required.Citation41 Acute FPIES can cause dehydration, leading to hemodynamic instability and a medical emergency. Aggressive isotonic fluid resuscitation may be required (10–20 mL/kg boluses of normal saline). In severe reactions, patients may require supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation for respiratory failure, vasopressors for hypotension, bicarbonate for acidemia, and methylene blue for methemoglobinemia.Citation41 Epinephrine autoinjectors are not recommended for FPIES unless the patient has an IgE-mediated allergy and is at risk for food-induced anaphylaxis. IV corticosteroids (methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg; maximum 60–80 mg) can be considered for severe reactions, although efficacy has not been established.Citation63 Ondansetron, a 5HT3 receptor antagonist with an anti-serotoninergic effect, can be considered. Ondansetron can reduce or prevent nausea and vomiting and the development of diarrhea.Citation80 It is recommended to administer 0.1–0.15 mg/kg IV or intramuscularly.Citation80 There is a lack of studies comparing ondansetron parenteral vs enteral route for FPIES-induced emesis. Although current data suggest that intravenous and intramuscular ondansetron forms have better efficacy, it is impractical in the home setting.Citation81 The International FPIES Association suggested in 2020, during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19 pandemic), to consider prescribing oral ondansetron to be used at home in case of an acute reaction.Citation81 After an acute episode, an emergency treatment plan that includes diagnosis and management should be provided to patients and parents that can be shown to physicians in emergencies. Educating caregivers is vital to avoid misdiagnosis of future episodes. Discussions should include the elimination of offending food protein, breastfeeding, formula choice, and time of reintroduction of the offending food.Citation80

FPIAP

Generally, patients with FPIAP have normal physical examination and blood testing. No acute intervention is usually required.Citation63

Long-Term Management

FPIES

Primary management consists of eliminating the trigger food from the infant’s diet (). Clinical history often helps identification of the trigger food. In contrast to FPIAP, FPIES is rare in breastfed infants. Most infants with FPIES tolerate allergens through breastfeeding without needing a maternal elimination diet.Citation82 Breastfeeding is encouraged, and maternal avoidance of the allergen is not recommended. Extensively hydrolyzed formulas are recommended for FPIES patients who can no longer breastfeed, have mild-to-moderate symptoms, and in the absence of faltering growth.Citation76 It is recommended to initiate with EHF, and if failing to resolve symptoms within 2 weeks, to switch to AAF.Citation80 For patients with severe symptoms, such as failure to thrive, AAF is the optimal initial choice.Citation80

Table 3 Food Triggers for FPIES, from Most to Least Common

For exclusively symptomatic FPIES occurring in breastfed infants, a maternal elimination diet of suspected trigger food should be implemented if reactions occur after breastfeeding or if an infant has failure to thrive.Citation41 The mother should consult with an allergy specialist and dietician. A hypoallergenic formula should be considered if a maternal elimination diet does not resolve symptoms.Citation41

There is no diagnostic testing for FPIES other than an oral food challenging test (OFCs), which would be recommended if the history is uncertain for a clear trigger food, or no symptom resolution with trigger food avoidance.Citation41 OFCs for FPIES are recommended every 12–18 months after the latest reaction to determine if the allergy has resolved.Citation43 OFCs should be done periodically to evaluate if the patient has developed tolerance to offending foods. For patients with FPE or FPIAP, foods can be gradually re-introduced at home. In FPIES, foods should be re-introduced under medical supervision due to the risk of hemodynamic instability.Citation2

For complementary feeding in FPIES, guidelines suggest introducing low-risk foods such as fruits and vegetables.Citation41 Foods of different colors, textures, and flavors should be continuously offered to avoid aversive feeding behaviors. It is recommended that caregivers introduce a new food as a single ingredient and wait at least 4 days before introducing another food to observe for development of a reaction.Citation41 Iron-rich foods should also be encouraged as FPIES patients are vulnerable to anemia.Citation83 The success of an elimination diet will depend on working with a dietitian, parental resources, number of allergens to avoid. Patients can benefit from nutritional guidance to avoid nutritional deficiencies like calcium, iron, and vitamin D.Citation80 A multidisciplinary approach in management that includes an allergist, dietician, nutritionist, and psychologist is the most successful way to ensure the growth and health of patients.Citation84

FPE

Management of FPE is the elimination of the offending food(s), which results in disease resolution within a few weeks.Citation28 EHF is the most appropriate formula choice with proved efficacy and cost-effectiveness.Citation85 However, if there is a severe reaction, failure to thrive or multiple allergies, then AAF should be considered.Citation28,Citation86 Infants should be rechallenged at 12 months of age, and most cases resolve within 1–3 years of age.Citation28

Tolerance Induction Strategies in Food Allergies

Oral tolerance induction has been explored in the contexts of prevention and treatment of food allergy. Early introduction of allergenic foods (ie, egg and peanut) in the diet of infants, before allergic sensitization occurs, has shown to be beneficial. Guidelines have changed to recommend the introduction of these allergenic foods by 6 months of age.Citation87

Although some guidelines suggest delaying introduction of additional common allergens empirically to prevent FPIES, this approach is not recommended.Citation88 Because IgE-mediated food allergy is more prevalent and generally more difficult to outgrow, the risk of developing an IgE-mediated allergy to foods such as peanut or egg outweighs the benefit of delayed introduction to manage or prevent FPIES. Rather, introducing commonly allergenic solids at around 6 months of age (and not before 4 months), especially if the child is at risk for IgE-mediated allergy, is recommended.Citation88

Tolerance induction strategies in food allergies through immunomodulatory treatments (like food oral immunotherapy (OIT), sublingual or epicutaneous immunotherapy) have been studied, but mainly in the context of Ig-mediated food allergy. So far, the efficacy of immunomodulatory treatments has been variable, with actual oral tolerance induction achieved in only a small proportion of allergic patients and side effects hampering further development or patients’ adherence to existing options. It remains to be proven whether immunotherapy can lead to long-term oral tolerance, where individuals may consume the food at any frequency in any amount without developing any allergic symptoms. A greater understanding of the immune mechanisms involved in food allergy and oral tolerance may lead us to a better efficacy and safety profile for future disease-modifying therapeutic approaches.Citation87,Citation89

Prognosis

The prognosis of FPIES, FPIAP, and FPE is generally good, with most of patients achieving tolerance during early childhood.Citation2 Patients with acute FPIES usually resolve within a few hours of rehydration. Patients with chronic FPIES improve within a few days to 2 weeks. The overall remission rate of FPIES ranges between 50% and 90% by the age of 6 years.Citation11 Atypical FPIES patients are at a considerable risk of developing IgE-mediated food reaction and can have a more protracted course.Citation90 Symptoms related to FPIAP, generally improve within 3 days of food elimination, but stool may completely normalized after 2 weeks.Citation31

On the other hand, FPE-related symptoms, in comparison to FPIES and FPIAP, take longer time to completely resolve. Malabsorption resulted from villous injury can serious and can take weeks to completely resolve following the offending protein elimination.Citation11 Long-term prognosis, however, is good: tolerance to the offending protein was achieved in the majority of infants by 2–3 years.Citation25

Conclusion

Although non-IgE-mediated food allergies are less common than IgE-mediated food allergies, these disorders are being increasingly recognized in children. FPIES, FPIAP, and FPE are the most common non-IgE-mediated food allergies seen in children. Generally, these disorders have a favorable prognosis; however, severe presentation such as shock as in acute form of FPIES or failure to thrive as in a chronic form of FPIES and FPE can be experienced. These disorders can cause significant healthcare burden and allergists should provide an accurate diagnosis with a clear therapy plan, and reassurance regarding the prognosis which is for most of the non-IgE-mediated conditions is excellent. A multidisciplinary team involving general pediatricians, dieticians, speech pathologists, and allergists/gastroenterologists is recommended when managing complex cases.

Abbreviations

FA, food allergy; IgE, immunoglobulin E; non-IgE-GI-FA, non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergic disorders; FPIES, food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; FPIAP, food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis; FPE, food protein-induced allergic enteropathy; OFC, oral food challenge; EHF, extensively hydrolyzed formula; AAF, amino acid-based-formula.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Nomura I, Morita H, Hosokawa S, et al. Four distinct subtypes of non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergies in neonates and infants, distinguished by their initial symptoms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(3):685–688.e1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.019

- Connors L, O’Keefe A, Rosenfield L, Kim H. Non-IgE-mediated food hypersensitivity. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2018;14(Suppl 2):56. doi:10.1186/s13223-018-0285-2

- Sampson HA, Aceves S, Bock SA, et al. Food allergy: a practice parameter update-2014. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(5):1016–1025.e43. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.013

- Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel - PubMed. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21134576/. Accessed August 30, 2022.

- Sabra A, Bellanti JA, Rais JM, Castro HJ, Mendez de Inocencio J, Sabra S. IgE and non-IgE food allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90(6, Supplement):71–76. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61664-X

- Morita H, Nomura I, Orihara K, et al. Antigen-specific T-cell responses in patients with non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergy are predominantly skewed to T(H)2. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(2):590–592.e1–6. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.09.005

- Muraro A, Werfel T, Hoffmann-Sommergruber K, et al. EAACI food allergy and anaphylaxis guidelines: diagnosis and management of food allergy. Allergy. 2014;69(8):1008–1025. doi:10.1111/all.12429

- Ruffner MA, Spergel JM. Non-IgE-mediated food allergy syndromes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117(5):452–454. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2016.04.014

- Chehade M, Meyer R, Beauregard A. Feeding difficulties in children with non–IgE-mediated food allergic gastrointestinal disorders. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122(6):603–609. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2019.03.020

- Squire JD, Stallings AP. Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome (FPIES) is associated with increased risk of feeding disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;141(2):AB132. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.422

- Feuille E, Nowak-Węgrzyn A. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome, allergic proctocolitis, and enteropathy. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015;15(8):50. doi:10.1007/s11882-015-0546-9

- Martin VM, Virkud YV, Seay H, et al. Prospective assessment of pediatrician-diagnosed food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis by gross or occult blood. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(5):1692–1699.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.12.029

- Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Berin MC, Mehr S. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(1):24–35. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.08.020

- Mehr S, Frith K, Barnes EH, Campbell DE; FPIES Study Group. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome in Australia: a population-based study, 2012–2014. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(5):1323–1330. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.03.027

- Katz Y, Goldberg MR, Rajuan N, Cohen A, Leshno M. The prevalence and natural course of food protein–induced enterocolitis syndrome to cow’s milk: a large-scale, prospective population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2011;127(3):647–653.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1105

- Alonso SB, Ezquiaga JG, Berzal PT, et al. Food protein–induced enterocolitis syndrome: increased prevalence of this great unknown—results of the PREVALE study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;143(1):430–433. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2018.08.045

- Mehr S, Frith K, Campbell DE. Epidemiology of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;14(3):208–216. doi:10.1097/ACI.0000000000000056

- Anvari S, Ruffner MA. adult food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. Front Allergy. 2022;3:889879. doi:10.3389/falgy.2022.889879

- Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Warren CM, Brown-Whitehorn T, Cianferoni A, Schultz-Matney F, Gupta RS. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome in the US population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(4):1128–1130. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2019.06.032

- González-Delgado P, Muriel J, Jiménez T, Cameo JI, Palazón-Bru A, Fernández J. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome in adulthood: clinical characteristics, prognosis, and risk factors. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(9):2397–2403. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2022.05.006

- Savilahti E. Food-Induced Malabsorption Syndromes. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30(1):S61. doi:10.1097/00005176-200001001-00010

- Schieve LA, Boulet SL, Boyle C, Rasmussen SA, Schendel D. Health of children 3 to 17 years of age with down syndrome in the 1997–2005 national health interview survey. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):e253–e260. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-1440

- Wakiguchi H, Hasegawa S, Kaneyasu H, et al. Long-lasting non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal cow’s milk allergy in infants with Down syndrome. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015;26(8):821–823. doi:10.1111/pai.12351

- Pecora V, Mennini M, Valentini D, et al. Food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome and down syndrome: an unexpected association? Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49(4):e268. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2017.09.069

- Verkasalo M, Kuitunen P, Savilahti E, Tiilikainen A. Changing pattern of cow’s milk intolerance. An analysis of the occurrence and clinical course in the 60s and mid-70s. Acta Paediatr. 1981;70(3):289–295. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.1981.tb16554.x

- Odze RD, Bines J, Leichtner AM, Goldman H, Antonioli DA. Allergic proctocolitis in infants: a prospective clinicopathologic biopsy study. Hum Pathol. 1993;24(6):668–674. doi:10.1016/0046-8177(93)90248-f

- Caubet JC, Szajewska H, Shamir R, Nowak-Węgrzyn A. Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergies in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2017;28(1):6–17. doi:10.1111/pai.12659

- Nowak-Węgrzyn A, Katz Y, Mehr SS, Koletzko S. Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(5):1114–1124. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.025

- Goldman H, Proujansky R. Allergic proctitis and gastroenteritis in children. Clinical and mucosal biopsy features in 53 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1986;10(2):75–86. doi:10.1097/00000478-198602000-00001

- Sicherer SH. Clinical aspects of gastrointestinal food allergy in childhood. Pediatrics. 2003;111(6 Pt 3):1609–1616. doi:10.1542/peds.111.S3.1609

- Lake AM. Food-induced eosinophilic proctocolitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;30(Suppl):S58–60. doi:10.1097/00005176-200001001-00009

- Lake AM, Whitington PF, Hamilton SR. Dietary protein-induced colitis in breast-fed infants. J Pediatr. 1982;101(6):906–910. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(82)80008-5

- Arvola T, Ruuska T, Keränen J, Hyöty H, Salminen S, Isolauri E. Rectal bleeding in infancy: clinical, allergological, and microbiological examination. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):e760–768. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1069

- Ravelli A, Villanacci V, Chiappa S, Bolognini S, Manenti S, Fuoti M. Dietary protein-induced proctocolitis in childhood. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(10):2605–2612. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02035.x

- Agyemang A, Nowak-Wegrzyn A. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;57(2):261–271. doi:10.1007/s12016-018-8722-z

- Ruffner MA, Wang KY, Dudley JW, et al. Elevated atopic comorbidity in patients with food protein-induced enterocolitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(3):1039–1046. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.10.047

- Schultz F, Westcott-Chavez A. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome from the parent perspective. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;14(3):263–267. doi:10.1097/ACI.0000000000000059

- Boyer J, Sgambelluri L, Yuan Q. Association of antibiotic usage with food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome development from a Caregiver’s survey. JPGN Rep. 2021;2(4):e132. doi:10.1097/pg9.0000000000000132

- Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Sampson HA, Wood RA, Sicherer SH. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome caused by solid food proteins. Pediatrics. 2003;111(4 Pt 1):829–835. doi:10.1542/peds.111.4.829

- Ocak M, Akarsu A, Sahiner UM, Soyer O, Sekerel BE. Phenotypes and natural history of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome in the east Mediterranean region. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2020;41(6):420–427. doi:10.2500/aap.2020.41.200078

- Nowak-Węgrzyn A, Chehade M, Groetch ME, et al. International consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: executive summary-workgroup report of the adverse reactions to foods committee, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(4):1111–1126.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.12.966

- Tan JA, Smith WB. Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food hypersensitivity syndrome in adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(3):355–357.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2014.02.002

- Labrosse R, Graham F, Caubet JC. Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergies in children: an update. Nutrients. 2020;12(7):2086. doi:10.3390/nu12072086

- Iyngkaran N, Robinson MJ, Sumithran E, Lam SK, Puthucheary SD, Yadav M. Cows’ milk protein-sensitive enteropathy. An important factor in prolonging diarrhoea of acute infective enteritis in early infancy. Arch Dis Child. 1978;53(2):150–153. doi:10.1136/adc.53.2.150

- Foong R-X, Meyer R, Dziubak R, et al. Establishing the prevalence of low vitamin D in non-immunoglobulin-E mediated gastrointestinal food allergic children in a tertiary centre. World Allergy Organ J. 2017;10(1):4. doi:10.1186/s40413-016-0135-y

- Meyer R, Godwin H, Dziubak R, et al. The impact on quality of life on families of children on an elimination diet for Non-immunoglobulin E mediated gastrointestinal food allergies. World Allergy Organ J. 2017;10(1):8. doi:10.1186/s40413-016-0139-7

- Murray KF, Christie DL. Dietary protein intolerance in infants with transient methemoglobinemia and diarrhea. J Pediatr. 1993;122(1):90–92. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83495-x

- Okura Y, Shimomura M, Takahashi Y, Kobayashi I. Usefulness of thymus and activation-regulated chemokine in solid food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2022;33(1):e13677. doi:10.1111/pai.13677

- Mathew M, Leeds S, Nowak-Węgrzyn A. Recent update in food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2022;14(6):587–603. doi:10.4168/aair.2022.14.6.587

- Makita E, Sugawara D, Kuroda S, Itabashi K, Ichihashi K. Usefulness of thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC) for FPIES diagnosis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2022;33(1):e13649. doi:10.1111/pai.13649

- Baudon JJ, Fontaine JL, Mougenot JF, Navarro J, Polonovski C, Laplane R. L'intolerance digestive aux proteines du lait de vache chez le nourrisson. Etude clinique de 42 cas [Digestive intolerance to cow’s milk proteins in infants. Biological and histological study]. Arch Fr Pediatr. 1975;32(9):787–801. French.

- Cetinkaya PG, Kahveci M, Karaatmaca B, et al. Predictors for late tolerance development in food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2020;41(1):e11–e18. doi:10.2500/aap.2020.41.190017

- Kimura M, Shimomura M, Morishita H, Meguro T, Seto S. Eosinophilia in infants with food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome in Japan. Allergol Int. 2017;66(2):310–316. doi:10.1016/j.alit.2016.08.003

- Beşer OF, Sancak S, Erkan T, Kutlu T, Cokuğraş H, Cokuğraş FÇ. Can fecal calprotectin level be used as a markers of inflammation in the diagnosis and follow-up of cow’s milk protein allergy? Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2014;6(1):33–38. doi:10.4168/aair.2014.6.1.33

- Trillo Belizón C, Ortega Páez E, Medina Claros AF, et al. Calprotectina fecal como apoyo al diagnóstico en la alergia a las proteínas de leche de vaca no IgE mediada [Faecal calprotectin as an aid to the diagnosis of non-IgE mediated cow’s milk protein allergy]. An Pediatr. 2016;84(6):318–323. French. doi:10.1016/j.anpedi.2015.07.007

- Calvani M, Anania C, Bianchi A, et al. Update on Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES). Acta Biomed. 2021;92(S7):e2021518. doi:10.23750/abm.v92iS7.12394

- Variend S, Placzek M, Raafat F, Walker-Smith JA. Small intestinal mucosal fat in childhood enteropathies. J Clin Pathol. 1984;37(4):373–377. doi:10.1136/jcp.37.4.373

- Iyngkaran N, Abdin Z, Davis K, et al. Acquired carbohydrate intolerance and cow milk protein-sensitive enteropathy in young infants. J Pediatr. 1979;95(3):373–378. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80509-0

- Calvani M, Anania C, Cuomo B, et al. Non-IgE- or mixed IgE/Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergies in the first years of life: old and new tools for diagnosis. Nutrients. 2021;13(1):226. doi:10.3390/nu13010226

- Su KW, Patil SU, Stockbridge JL, et al. Food aversion and poor weight gain in food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: a retrospective study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(5):1430–1437.e11. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.01.001

- Ruffner MA, Ruymann K, Barni S, Cianferoni A, Brown-Whitehorn T, Spergel JM. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: insights from review of a large referral population. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(4):343–349. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2013.05.011

- Ludman S, Harmon M, Whiting D, du Toit G. Clinical presentation and referral characteristics of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome in the United Kingdom. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113(3):290–294. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2014.06.020

- Abrams EM, Hildebrand KJ, Chan ES. Non-IgE-mediated food allergy: evaluation and management. Paediatr Child Health. 2021;26(3):173–181. doi:10.1093/pch/pxaa131

- Miceli Sopo S, Romano A, Bersani G, et al. Cooking influence in tolerance acquisition in egg-induced acute food protein enterocolitis syndrome. Allergol Immunopathol. 2019;47(3):221–226. doi:10.1016/j.aller.2018.07.006

- Corica D, Aversa T, Caminiti L, Lombardo F, Wasniewska M, Pajno GB. Nutrition and avoidance diets in children with food allergy. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:518. doi:10.3389/fped.2020.00518

- Caubet JC, Ford LS, Sickles L, et al. Clinical features and resolution of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: 10-year experience. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(2):382–389. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2014.04.008

- Fiocchi A, Barrio-Torres J, Dupont C, et al. Hydrolyzed rice formula for dietary management of infants with cow’s milk allergy. World Allergy Organ J. 2022;15(12):100717. doi:10.1016/j.waojou.2022.100717

- Meyer R, Chebar Lozinsky A, Fleischer DM, et al. Diagnosis and management of Non-IgE gastrointestinal allergies in breastfed infants-An EAACI position paper. Allergy. 2020;75(1):14–32. doi:10.1111/all.13947

- Mennini M, Fiocchi AG, Cafarotti A, et al. Food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis in infants: literature review and proposal of a management protocol. World Allergy Organ J. 2020;13(10):100471. doi:10.1016/j.waojou.2020.100471

- Nowak-Węgrzyn A. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome and allergic proctocolitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2015;36(3):172–184. doi:10.2500/aap.2015.36.3811

- Miceli Sopo S, Monaco S, Bersani G, Romano A, Fantacci C. Proposal for management of the infant with suspected food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2018;29(2):215–218. doi:10.1111/pai.12844

- Lozinsky AC, Meyer R, De Koker C, et al. Time to symptom improvement using elimination diets in non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergies. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015;26(5):403–408. doi:10.1111/pai.12404

- Zubeldia-Varela E, Barker-Tejeda TC, Blanco-Pérez F, Infante S, Zubeldia JM, Pérez-Gordo M. Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food protein-induced allergic disorders. clinical perspectives and analytical approaches. Foods. 2021;10(11):2662. doi:10.3390/foods10112662

- Meyer R, Groetch M, Venter C. When should infants with cow’s milk protein allergy use an amino acid formula? A practical guide. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(2):383–399. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.09.003

- Leung A, Otley A; Canadian Paediatric Society. Concerns for the use of soy-based formulas in infant nutrition. Paediatr Child Health. 2009;14(2):109–118. doi:10.1093/pch/14.2.109

- Venter C, Brown T, Shah N, Walsh J, Fox AT. Diagnosis and management of non-IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy in infancy - a UK primary care practical guide. Clin Transl Allergy. 2013;3(1):23. doi:10.1186/2045-7022-3-23

- Espín Jaime B, Díaz Martín JJ, Blesa Baviera LC, et al. Alergia a las proteínas de leche de vaca no mediada por IgE: documento de consenso de la Sociedad Española de Gastroenterología, Hepatología y Nutrición Pediátrica (SEGHNP), la Asociación Española de Pediatría de Atención Primaria (AEPAP), la Sociedad Española de Pediatría Extrahospitalaria y Atención Primaria (SEPEAP) y la Sociedad Española de Inmunología Clínica, Alergología y Asma Pediátrica (SEICAP) [Non-IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy: consensus document of the Spanish Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (SEGHNP), the Spanish Association of Paediatric Primary Care (AEPAP), the Spanish Society of Extra-hospital Paediatrics and Primary Health Care (SEPEAP), and the Spanish Society of Paediatric ClinicaL Immunology, Allergy, and Asthma (SEICAP)]. An Pediatr. 2019;90(3):193.e1–193.e11. Spanish. doi:10.1016/j.anpedi.2018.11.007

- Stróżyk A, Ruszczyński M, Horvath A, et al. World Allergy Organization (WAO) Diagnosis and Rationale for Action against Cow’s Milk Allergy (DRACMA) Guidelines update – IV – a quality appraisal with the AGREE II instrument. World Allergy Organ J. 2022;15:2. doi:10.1016/j.waojou.2021.100613

- Mehr S, Brown-Whitehorn T. What do allergists in practice need to know about non-IgE-mediated food allergies. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;122(6):589–597. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2019.03.025

- Michelet M, Schluckebier D, Petit LM, Caubet JC. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome - a review of the literature with focus on clinical management. J Asthma Allergy. 2017;10:197–207. doi:10.2147/JAA.S100379

- Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Cianferoni A, Bird JA, Fiocchi A, Caubet JC; Medical Advisory Board of the International FPIES Association. Managing food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: expert recommendations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;125(1):14–16. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2020.04.032

- Kaya A, Toyran M, Civelek E, Mısırlıoglu ED, Kırsaçlıoglu CT, Kocabaş CN. Food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome in two exclusively breastfed infants. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27(7):749–750. doi:10.1111/pai.12605

- Baker RD, Greer FR; Committee on Nutrition American Academy of Pediatrics. Diagnosis and prevention of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in infants and young children (0–3 years of age). Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):1040–1050. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-2576

- Staceyrivers. Controversies on special products for managing cow’s milk protein allergy in infants: safety and suitability. EMJ. 2017;2(1):46–51. doi:10.33590/emjallergyimmunol/10313836

- Sackesen C, Altintas DU, Bingol A, et al. Current trends in tolerance induction in cow’s milk allergy: from passive to proactive strategies. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:372. doi:10.3389/fped.2019.00372

- Kansu A, Yüce A, Dalgıç B, Şekerel BE, Çullu-çokuğraş F, Çokuğraş H. Consensus statement on diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of cow’s milk protein allergy among infants and children in Turkey. Turk J Pediatr. 2016;58(1):1–11. doi:10.24953/turkjped.2016.01.001

- Foong RX, Santos AF. Oral tolerance induction-opportunities and mechanisms. Foods. 2022;11(21):3386. doi:10.3390/foods11213386

- Abrams EM, Hildebrand K, Blair B, Chan ES. Timing of introduction of allergenic solids for infants at high risk. Paediatr Child Health. 2019;24(1):56–57. doi:10.1093/pch/pxy195

- Nowak-Węgrzyn A, Chatchatee P. Mechanisms of tolerance induction. Ann Nutr Metab. 2017;70(Suppl 2):7–24. doi:10.1159/000457915

- Sicherer SH, Eigenmann PA, Sampson HA. Clinical features of food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome. J Pediatr. 1998;133(2):214–219. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70222-7