Abstract

Background

The objective was to perform a systematic review in order to describe the relationship between asthma and sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) in children, especially regarding the impact of treatment and management.

Methods

We performed an electronic search in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and LILACS database. Study inclusion criteria were the following: 1) studies that examined the relationship between asthma/wheezing and SDB/obstructive sleep apnea (OSA); and 2) studies conducted in children <18 years of age. Primary outcomes were the prevalence of asthma and SDB, the tests used for diagnosis, and the influence of their treatment and management.

Results

One thousand and twenty studies were identified, among which 32 were selected (n=143,343 children; 51% males; age [mean ± standard deviation] 8.4±2.5 years). Most studies (n=26) diagnosed SDB using questionnaires or clinical history. Nine studies performed a sleep study for diagnosing OSA. The diagnosis of asthma was based on clinical history (n=16), previous medical diagnosis (n=4), questionnaires (n=12), and spirometry (n=5). Children with asthma were more likely to develop habitual snoring and OSA, and children with SDB were more likely to develop asthma. Moreover, asthma was associated with more severe OSA, and the presence of SDB was associated with severe asthma. Treatment of SDB with adenotonsillectomy was associated with significant asthma improvement.

Conclusion

The relationship between asthma and SDB appears to be bidirectional, and adenotonsillectomy appears to improve asthma control. Future trials on how asthma treatment could impact on SDB are needed.

Introduction

Asthma is known to be one of the most common chronic diseases in childhood.Citation1 Asthma most frequently starts early in life and has a variable clinical evolution and different phenotypes which may progress or remit over time.Citation2 Around half of preschool wheezers become asymptomatic by school age irrespective of treatment.Citation3 However, asthma symptoms (eg, sleep disturbance and cough at night) may persist, often lifelong, especially among atopic children and in more severe cases. The impact of asthma on the quality of life and health cost of patients is very high.Citation4,Citation5 Therefore, appropriate asthma management may have a major impact on the quality of life of patients and their families, as well as on public health outcomes.Citation3

On the other hand, sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) is also a prevalent disease in children.Citation6 Similar to asthma, SDB has a broad clinical presentation, ranging from primary snoring to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).Citation7 The cardinal symptom of SDB is habitual snoring (ie, snoring in more than three nights weekly). Similar to asthma, symptoms of SDB may remain unrecognized for a long time.Citation8 Treatment of SDB, for example, adenotonsillectomy (AT), often resolves snoring and concomitant symptoms. However, a large multicenter study in asthmatic childrenCitation9 showed that SDB may persist even after AT.

Furthermore, asthma and SDB may coexist, as they are both inflammatory diseases of the lower and upper airway tract, respectively.Citation10 Similar symptoms during the night may also lead to confusion in clinical history. The similarities and parallel rise of prevalence of both diseases in the last decades arise the question that if there is a relationship between asthma and SDB.Citation11

Therefore, we launched the present systematic review, in order to describe the relationship between asthma and SDB, especially regarding the impact of treatment and management of these diseases.

Methods

Search and selection criteria

We identified all published studies in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and LILACS (up to November 2015) database, using following keywords: “(asthma OR wheezing) AND (sleep) AND (obstructive sleep apnea OR sleep disordered breathing) AND (children OR child OR adolescent)”. Studies published solely in abstract form were excluded because methods and results could not be fully analyzed. To be included, studies had to meet all the following criteria: case–control, cohort, or intervention studies that examined the relationship between asthma/wheezing and SDB/OSA in subjects aged <18 years of age; and all kinds of treatments were accepted (especially AT, considered the first-line treatment for SDB). No language restriction for the studies was applied. We excluded studies in which participants had any other chronic underlying disease such as craniofacial abnormalities, neurological disorders, dysmorphic genetic disorders or metabolic disorders, or other chronic respiratory illness different from asthma/wheezing. All references were managed by reference manager software (Mendeley® 1.14; Elsevier Inc, Philadelphia, PA, USA).

Target conditions

Childhood asthma was accepted as a clinical diagnosis (ie, “chronic inflammatory disease of the lower respiratory tract with recurrent or persistent wheezing”).Citation3 Most of the studies usually diagnosed asthma by questionnaire. On the other hand, SDB was defined according to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-third editionCitation12 (ie, habitual snoring, upper airway resistance syndrome, and OSA). It was accepted that SDB diagnosis was made clinically or through questionnaire or polysomnography (PSG).

Our primary outcomes were 1) prevalence of asthma and SDB (using different tests for their diagnoses), 2) asthma as a risk factor for SDB and vice versa, and 3) the influence of their management.

Data extraction and assessment of risk of bias

Titles, abstracts, and citations were independently analyzed by two authors (TS and PEB). Based on the full-text form, all studies were evaluated for inclusion/exclusion criteria, type of intervention, population included, study design, and outcomes. After obtaining full reports about potentially relevant trials, eligibility was assessed. Disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus.

Results

Studies description

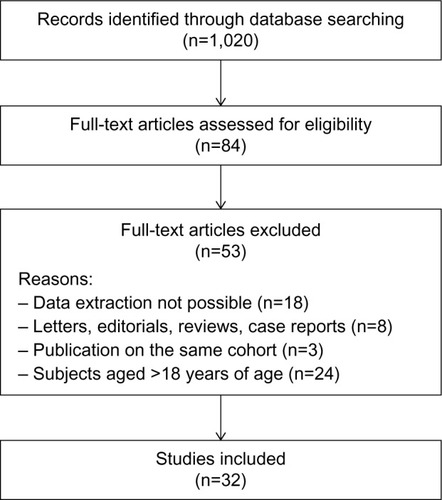

In total, 1,020 (n) studies were identified. Among those, 32 (N) studiesCitation9,Citation10,Citation13–Citation42 met the inclusion criteria (). The studies included a total of 143,343 children (51.3% were males) of age (mean ± standard deviation) 8.4±2.5 years. Fourteen studies came from USA,Citation9,Citation22,Citation24,Citation25,Citation29,Citation31,Citation34–Citation36,Citation38–Citation42 nine from Asia,Citation13,Citation14,Citation18,Citation20,Citation28,Citation30,Citation32,Citation33,Citation37 seven from Europe,Citation10,Citation15–Citation17,Citation19,Citation23,Citation26 and two from Oceania.Citation21,Citation27 Almost all studies diagnosed SDB using questionnaires (ie, the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire [PSQ]),Citation18,Citation29,Citation32,Citation33 clinical history,Citation10,Citation13–Citation17,Citation19–Citation23,Citation26–Citation28,Citation35 or previous medical diagnosis.Citation36,Citation38,Citation39,Citation42 Eight studies performed PSG,Citation9,Citation24,Citation30,Citation31,Citation34,Citation37,Citation40,Citation41 and only one, a home cardiorespiratory polygraphy.Citation25 On the other hand, the diagnosis of asthma was based on clinical history exclusively in 16 studies,Citation9,Citation10,Citation15,Citation17,Citation19,Citation23–Citation26,Citation30–Citation32,Citation35,Citation39,Citation40,Citation42 previous medical asthma diagnosis in four studies,Citation20,Citation29,Citation36,Citation38 general questionnaires in six studies,Citation14,Citation15,Citation17,Citation18,Citation21,Citation33 and the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in ChildhoodCitation43 questionnaire in six studies.Citation13,Citation16,Citation22,Citation27,Citation28,Citation34 Only five studies performed spirometry for assessing asthma.Citation16,Citation22,Citation25,Citation34,Citation41

Studies on association and/or risk of SDB in asthmatics

shows the studies that investigated the association between asthma and SDB.Citation9,Citation10,Citation16,Citation21,Citation24,Citation25,Citation27–Citation32,Citation34,Citation35,Citation37 The aim of eleven studies was to describe the prevalence and risk factors of SDB, among which we were able to find data on asthma.Citation13–Citation15,Citation17,Citation18,Citation20,Citation22,Citation26,Citation33,Citation40,Citation41 gives the result of them.

Table 1 Association of asthma and SDB

Table 2 Prevalence of SDB and asthma as a risk factor

Overall, the studies showed that children with asthma/wheeze were more likely to have a higher risk for habitual snoring and OSA than those without asthma. For example, a study in Belgian childrenCitation28 reported that wheezing was related to an increased risk of snoring (odds ratio [OR] =2.8, 95% CI 1.1–2.6). A study on Austrian childrenCitation27 showed a strong and significant association between SDB symptoms and wheeze/asthma, especially between snoring (OR =5.4, 95% CI 3.6–8.1) and snorting (OR =5.3, 95% CI 2.6–10.8) with wheezing in the last 12 months. In another study, children with wheezing had a significantly higher prevalence of snoring, and more nocturnal awakenings than non-wheezing children (46% vs 26% and 30% vs 20%, respectively); after multiple logistic regression analysis, wheeze remained as a risk factor for difficulties falling asleep (OR =2.0, 95% CI 1.0–4.0), restless sleep (OR =5.0, 95% CI 2.2–11.1), daytime sleepiness (OR =3.8, 95% CI 1.8–8.0), and tiredness (OR =5.1, 95% CI 2.2–12.1).Citation16 Asthma was also associated with tonsillar hypertrophy. In a prospective cohort of 442 Greek children who consulted the emergency department (ED) and pulmonology clinic, history of wheezing was significantly associated with the presence of tonsillar hypertrophy and snoring (OR =2.36, 95% CI 1.46–3.79 and OR =1.88, 95% CI 1.24–2.86, respectively).Citation10 When questionnaires (eg, PSQ) were used,Citation29 the prevalence of a positive test (>0.33) was significantly higher in asthmatic children than in non- asthmatic children (25.9% vs 10.6%, P<0.001, respectively; OR =2.94, 95% CI 1.82–4.75). Interestingly, the effect of asthma was “dose dependent”, as children with more severe asthma had increased OR for snoring and a positive PSQ.

Studies using PSG to determine SDB showed similar results. A study in 50 African-American childrenCitation34 concluded that poorly controlled asthma was associated with more severe OSA; a history of lifetime asthma increased the apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) by 8.8 (P<0.005) in the PSG. A studyCitation24 that investigated parameters of sleep fragmentation by PSG concluded that asthmatic snorer’s children had worse sleep quality as judged by indices of sleep fragmentation than those without asthma. Moreover, a study of OSA diagnosed by PSG in a sleep center in the USACitation31 reported that maximal %SpO2 rapid-eye-movement (REM) desaturation, REM–obstructive AHI, and prevalence of REM-related OSA were significantly increased in asthmatic children with OSA compared to subjects with only OSA, showing that asthma is associated with REM-related breathing abnormalities in children with moderate–severe OSA. A cross-sectional studyCitation37 that investigated sleep quality by PSG in children aged 6–12 years found that asthmatics had significantly longer sleep latency and less slow-wave sleep compared with non-asthmatics; also, asthmatics (either with or without OSA) had significantly more leg movement than non-asthmatics. This study supports the hypothesis that nonobese asthmatic children, with or without OSA, may exhibit poor sleep quality as compared with nonobese non-asthmatic children. There is a known seasonal variability described in SDB.Citation44 In our studies, asthma and atopy did not explain this variation. Greenfeld et alCitation30 in a review on 2,178 PSG of children and adolescents referred for suspected SDB, with a prevalence of asthma of 18%, found that the mean obstructive AHI in the winter was significantly higher compared to the summer (9.1±9.6 vs 7.5±7.0, P=0.01; Cohen d=0.19), particularly in children younger than the age of 5 years (10.2±10.5 vs 7.9±7.3, P=0.008; Cohen d=0.25), and asthma/atopy had no significant effect on seasonal variability.

In contrast to the studies described, only one study showed that a history of asthma decreased the likelihood of OSA.Citation24 That was a retrospective review of patients referred to a sleep laboratory for an overnight PSG, and it compared the definition of OSA as an AHI >2 or >5. No significant differences in OSA prevalence or severity for asthmatics compared to non-asthmatics were found. The authors of that study explained these findings due to a possible referral bias; since parents of asthmatics would be more vigilant regarding night-time symptoms, they may have mistaken night noises (asthma symptoms and noisy breathing) for snoring, having an “over”-report of night symptoms.

Studies on association and/or risk of asthma in children with SDB

Children with SDB were more likely to develop asthma/wheeze than those without asthma/wheeze. Lu et alCitation21 reported that 42.2% of children who snored had asthma (OR =2.03, 95% CI 1.34–3.10). There was also a highly significant association between snoring and nocturnal cough (OR =3.68, 95% CI 2.41–5.63). In that study, nocturnal cough was strongly associated with asthma; in the asthmatic group, the prevalence of nocturnal cough was significantly higher among children who snored vs children who did not snore (86.1% vs 52.6%, respectively, P=0.001; OR =5.56, 95% CI 2.26–13.67). Sulit et alCitation25 in a US community-based cohort study of 788 participants (aged 8–11 years) found that children with SDB had nearly twice the odds of wheeze compared with those without SDB (OR =1.89, 95% CI 1.26–2.85). Recently, a large Chinese epidemiological studyCitation32 (n=20,672 children, mean age 9.0±1.61 years) concluded that habitual snoring and OSA remained a statistically significant predictor of asthma (OR =1.28, 95% CI 1.01–1.62 and OR =1.92, 95% CI 1.34–2.76, respectively). In a prospective study on 108 asthmatic patients (mean age 9.1±3.4 years), children with SDB had more than three times the risk for having severe asthma at follow-up (OR =3.62, 95% CI 1.26–10.4).Citation35

Only three studies that analyzed risk factors for asthma development investigated SDB.Citation19,Citation23,Citation36 Those results are given in the following. In the study of Hoskyns et al,Citation19 the relationship between night cough and other indices of asthma severity was studied in 21 children with clinically stable asthma and persistent night cough; there was an association of SDB with asthma. A study aimed to develop an asthma prediction tool for preschoolers with wheeze or cough; snoring resulted as a predictive factor for asthma 5 years later (77.4% vs 69.6%, asthma vs no asthma, P=0.006).Citation23 Finally, a retrospective cohort studyCitation36 of asthmatic children (n=25,900) who required hospitalization showed a higher risk of hospital length of stay >2 days (OR =2.3, 95% CI 1.8–2.9) for those with previous diagnosis of OSA (1.4% of the group) than those without OSA. The authors of that study suggested that children with OSA and asthma experience a higher severity of nocturnal hypoxemia and hypoventilation; therefore, it may possibly take longer time to return to an acceptable respiratory status after an asthma crisis.

Studies on therapy

shows the results from the studies analyzing treatment’s impact. No studies of asthma treatment that influence SDB were found. On the other hand, five studies investigated the effect of AT in asthma control.Citation9,Citation38–Citation40,Citation42 Bhattacharjee et alCitation38 conducted a large study of asthmatic children (n=13,506) who underwent AT, and the surgical procedure was associated with significant reductions in acute asthmatic exacerbations (30.2%, 95% CI 25.6%-34.3%; P<0.0001), acute status asthmaticus (37.9%, 95% CI 29.2%–45.6%; P<0.0001), asthma-related ED visits (25.6%, 95% CI 16.9%–33.3%; P <0.0001), and asthma-related hospitalizations (35.8%, 95% CI 19.6%–48.7%; P=0.02). Moreover, AT was associated with significant reductions in most asthma prescription refills, including bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids, leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs), and systemic corticosteroids. Kheirandish-Gozal et alCitation40 conducted a prospective study on 92 poorly controlled asthma children (aged 3–10 years) with a mean frequency of acute asthmatic exacerbations of 3.4±0.4/year. Overnight PSG revealed the presence of OSA (AHI >5/hour of total sleep time) in 63.0% of patients (OR =40.9, 95% CI 12.9–144.1) compared to the maximal estimated prevalence of OSA in a non-asthmatic population. From this group, information at 1-year follow-up was available for 35 asthmatics with OSA after AT, and for 24 without OSA. The annual frequency of acute asthmatic exacerbations in the post-AT subgroup significantly decreased (from 4.1±1.3 to 1.8±1.4/year, P< 0.0001), with no changes in the non-OSA group. Similar favorable improvement occurred after AT in the frequency of β-agonist rescue use or in asthma symptom scores. Busino et alCitation39 reviewed retrospectively 560 children who underwent AT; 16,6% were asthmatics, 97.8% of this group underwent AT for OSA. AT was associated with significant reductions in asthma therapies, including corticosteroids, and with improvements in asthma control test scores.

Table 3 Studies on impact of treatment of SDB and asthma

Discussion

In this systematic review of 32 studies, we found a mean prevalence of asthma of 33.2%, and of SDB 41.8%. Asthma is estimated to affect 7.1 million US children under the age of 18 years.Citation1 The prevalence of asthma in children varies through different countries. In the studies we reviewed, the asthma prevalence ranged from 8.8% in BelgiumCitation16 to 28% in Australia.Citation21

On the other hand, the prevalence of snoring is estimated to be 3.2%–12.1%, and the prevalence of OSA ranges from 0.7% to 10.3%.Citation45 When parents were asked about habitual snoring (usually three or four times per week), the prevalence reported in the studies of this systematic review was 6% in a group of Singapore children,Citation14 7% in Turkey,Citation17 10.1% in Germany,Citation26 12% in the People’s Republic of China,Citation20,Citation21,Citation32,Citation33 14.6% in Australia,Citation22 and 28% in Belgium.Citation16 When standardized questionnaires were used (eg, the PSQ), the prevalence of SDB symptoms was 14.9% in Malaysia.Citation18 However, PSG is known to be the gold standard for SDB but has important limitations due to availability and cost. This may explain the reason why only a few studies in our systematic review used it for SDB and OSA diagnosis. Redline et alCitation41 reported the prevalence of SDB in a general population of children in the USA to be 1.6% and 10.3% by using a PSG diagnostic criteria of AHI >10 and 5, respectively.

In order to discuss the current evidence of an association between SDB/OSA and asthma, it is important to mention the definitions of sleep-related breathing disorders. Childhood SDB is a spectrum of abnormal breathing patterns during sleep that ranges from primary snoring to OSA. OSA in children is an SDB characterized by prolonged partial upper airway obstruction and/or intermittent complete obstruction that affects normal ventilation during sleep.Citation46 OSA is considered the most severe disease within the spectrum of SDB. It is associated with symptoms including habitual snoring, sleep difficulties, and daytime neurobehavioral problems and has the potential to result in serious long-term consequences, such as cognitive deficits, academic failure, cardiovascular complications, and metabolic syndrome.

There is a growing body of evidence of an association between SDB and asthma, supported by most of the studies described in our review. Our previous systematic review on prevalence of asthma and SDB including 17 studies involving 45,155 children found that children with asthma had a significantly higher risk of SDB (OR =1.9, 95% CI 1.2–2.2).Citation47 However, the relationship between asthma and SDB appears bidirectional. SDB, especially OSA, may exacerbate asthma by altering oropharyngeal reflexes and increasing negative intrathoracic pressure, increasing cholinergic tone, and promoting bronchoconstriction.Citation14 Studies like the one by Pescatore et al reinforce that SDB may even predict asthma development.Citation23 In addition, a large retrospective cohort showed that SDB may even prolong the recovery of children after hospitalization due to asthma.Citation36

On the other hand, we found many studies showing that asthma may exacerbate SDB disrupting sleep, resulting in sleep deprivation and increasing the frequency of apneas in snorers.Citation14 Also, poorly controlled asthma might accentuate the hypoxemia in SDB and vice versa; intermittent nocturnal hypoxemia in children with OSA could initiate and maintain upper and lower airway inflammation.Citation48,Citation49

Therefore, this bidirectional association may be explained due to common risk factors that promote airway inflammation, sharing a common pathogenetic pathway. This is referred as the “one-airway” hypothesis, suggesting that upper airway inflammation and intermittent hypoxia from obstruction may influence the expression and severity of disease of the lower respiratory tract.Citation50,Citation51 Lower and upper airway inflammation is related to atopy and incremented cysteinyl leukotriene activity, and can lead to decreased lower airway caliber and increased nasal resistance and pharyngeal collapsibility,Citation52–Citation54 predisposing to wheeze and snore during sleep. Also, adenotonsillar hypertrophy increases upper airway resistance and is the first cause of SDB in children. It seems that asthma is associated with tonsillar hypertrophy,Citation10 and children with history of wheezing have larger tonsils than subjects without wheezing. Hypertrophic tonsils could mediate at least in part the known association between asthma and obstructive SDB in childhood. This is reinforced by two studies,Citation55,Citation56 demonstrating that increased cysteinyl leukotrienes activity is present in tonsils excised from children with OSA, seeming to promote tonsillar cell proliferation.

In addition to what we already knew concerning the possible relationship of asthma and SDB,Citation49 we aimed to analyze in the present systematic review how treatment impacts on both diseases. We found several studies addressing how SDB treatment impacts on asthma. However, no studies were found so far that compared how asthma treatment impacts on SDB.

The first-line treatment for OSA in children is AT (if the patient has demonstrated adenotonsillar hypertrophy and does not have contraindications to surgery).Citation15,Citation46 In the past years, there has been increasing interest in studying the effect of AT, as first-line SDB/OSA treatment, and improvement of childhood asthma.Citation38–Citation40 Kheirandish-Gozal et alCitation40 demonstrated that the annual frequency of acute asthmatic exacerbations in children post-AT decreased significantly compared to those without AT. Based on this interesting study, one may hypothesize that upper airway inflammatory processes may play a role in lower airway inflammation and asthma, and conversely, lower airway inflammatory disease may promote adenotonsillar proliferation, and therefore increase the propensity for OSA.Citation40 Therefore, treatment of OSA may benefit control of asthma. In a study of Bhattacharjee et alCitation38 on 13,506 children with asthma, only 6.2% of those who underwent AT and 0.6% of those who did not undergo the surgical procedure had some form of evaluation for SDB as determined by searching for specific sleep diagnostic testing. This finding shows that most patients are operated without having a sleep diagnosis, even if they are scheduled for a surgical procedure. Considering that asthmatics might have a higher prevalence and severity of OSA, a formal sleep study should be considered case by case, especially before surgical procedures. In another multicenter study by Bhattacharjee et alCitation9 (n=578 children), the presence of asthma was a significant factor for persisting with OSA after AT, and the study underlined the importance of a post-AT PSG in children with asthma undergoing AT. A longitudinal observational studyCitation42 on 130 children (aged 2–18 years), both with and without asthma, undergoing AT showed that asthma control test scores and chitinase activity in the circulation (biomarkers of airway inflammation, such as upper airway and asthmatic disease) measured at time of surgery and at 6-month follow-up had a significant improvement. A significant improvement in asthma control test scores after 6 months and decrease in several asthma-related outcomes (eg, rate of ED visits, oral corticosteroid courses, missed school days due to asthma, and total missed parental work days) and in circulating chitinase activity (median decrease 0.4 nmol/L/mL/h, P<0.01) suggest that AT also may modulate airway inflammation in asthma. These studies support the idea that detection and treatment of adenotonsillar tissue hypertrophy may serve as an important strategy for improving asthma control. However, randomized controlled studies are needed to confirm this.

There are certainly other treatment for OSA (ie, nasal corticosteroids spraysCitation57,Citation58 and LTRAs).Citation59 Dental devices or oral appliance therapy, surgical procedures, and continuous positive airway pressure may be considered as second-line treatment. Most of them have specific indications for patients with specific chronic diseases (eg, neuromuscular disorders). We did not find eligible studies of these treatments in patients with asthma and SDB.

The present study, as usual in this kind of systematic reviews, has limitations that need to be addressed. We made the highest effort in finding most available studies on the topic. However, there are some interesting studies that might have escaped our search strategy. Prevalence of asthma and SDB was originally calculated only in some studies; we recalculated it from the data of several other included studies. Hence, this may have biased this outcome, as some studies were not intended as epidemiologic studies for prevalence estimation. In most included studies, asthma and SDB were among a long list of factors analyzed, but only few studies aimed to analyze specifically the relationship between them. Hence, a data extraction bias is also possible. Future studies specifically designed for demonstrating the bidirectional relationship between both diseases may help to confirm our results. As mentioned earlier, only studies that analyzed AT as treatment for SDB were found. Therefore, we do not know if other therapeutic options for SDB, for example, nasal corticosteroids, LTRAs, or maxillary interventions, may have some influence on asthma.

Conclusion

The present systematic review shows that asthma and SDB are both very frequent conditions in childhood, and may have a bidirectional relationship. Treatment of SDB seems to impact positively on the clinical evolution of asthma in children. It is yet to be proven whether or not optimizing asthma control could prevent consequences of SDB.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- AkinbamiLJMoormanJEBaileyCTrends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 2001–2010.NCHS Data Brief2012941822617340

- Castro-RodriguezJAGarcia-MarcosLWheezing and asthma in childhood: an epidemiology approachAllergol Immunopathol (Madr)200836528029019080801

- PapadopoulosNGArakawaHCarlsenKHInternational consensus on (ICON) pediatric asthmaAllergy201267897699722702533

- JanssensTHarverAEffects of symptom perception interventions on trigger identification and quality of life in children with asthmaPulm Med2015201582513726605084

- AsherIPearceNGlobal burden of asthma among childrenInt J Tuberc Lung Dis201418111269127825299857

- LumengJCChervinRDEpidemiology of pediatric obstructive sleep apneaProc Am Thorac Soc20085224225218250218

- MarcusCLSleep-disordered breathing in childrenAm J Respir Crit Care Med20011641163011435234

- Montgomery-DownsHEO’BrienLMHolbrookCRGozalDSnoring and sleep-disordered breathing in young children: subjective and objective correlatesSleep2004271879414998242

- BhattacharjeeRKheirandish-GozalLSpruytKAdenotonsillectomy outcomes in treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children: a multicenter retrospective studyAm J Respir Crit Care Med2010182567668320448096

- KaditisAGKalampoukaEHatzinikolaouSAssociations of tonsillar hypertrophy and snoring with history of wheezing in childhoodPediatr Pulmonol201045327528020131382

- TeodorescuMPredictors of habitual snoring and obstructive sleep apnea risk in patients with asthmaChest J200913551125

- SateiaMJInternational classification of sleep disorders-third edition: highlights and modificationsChest201414651387139425367475

- BidadKAnariSAghamohamadiAGholamiNZadhushSMoaieriHPrevalence and correlates of snoring in adolescentsIran J Allergy Asthma Immunol20065312713217237564

- ChngSYGohDYTWangXSTanTNOngNBHSnoring and atopic disease: a strong associationPediatr Pulmonol200438321021615274099

- CorboGMForastiereFAgabitiNSnoring in 9- to 15-year-old children: risk factors and clinical relevancePediatrics200110851149115611694695

- DesagerKNNelenVWeylerJJJDe BackerWASleep disturbance and daytime symptoms in wheezing school-aged childrenJ Sleep Res2005141778215743337

- ErsuRArmanARSaveDPrevalence of snoring and symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing in primary school children in ItanbulChest20041261192415249437

- FadzilAJamalludinANorrashidahAPrevalence of sleep disordered breathing symptoms among Malay school children in a primary school in MalaysiaMed J Malaysia201267218118522822640

- HoskynsEWBeardsmoreCSSimpsonHChronic night cough and asthma severity in children with stable asthmaEur J Pediatr199515443203257607286

- LiSJinXYanCWuSJiangFShenXHabitual snoring in school-aged children: environmental and biological predictorsRespir Res201011114420955625

- LuLRPeatJKSullivanCESnoring in preschool children: prevalence and association with nocturnal cough and asthmaChest2003124258759312907547

- MarshallNSAlmqvistCGrunsteinRRMarksGBPredictors for snoring in children with rhinitis at age 5Pediatr Pulmonol200742758459117534968

- PescatoreAMDogaruCMDuembgenLA simple asthma prediction tool for preschool children with wheeze or coughJ Allergy Clin Immunol20141331111.e13118.e1323891353

- RamagopalMScharfSMRobertsDWBlaisdellCJObstructive sleep apnea and history of asthma in snoring childrenSleep Breath200812438139218421491

- SulitLGStorfer-IsserARosenCLKirchnerHLRedlineSAssociations of obesity, sleep-disordered breathing, and wheezing in childrenAm J Respir Crit Care Med2005171665966415591475

- UrschitzMSRisk factors and natural history of habitual snoringChest2004126379015364758

- ValeryPCMastersIBChangABSnoring and its association with asthma in Indigenous children living in the Torres Strait and Northern Peninsula AreaJ Paediatr Child Health200440January46146515265188

- VerhulstSLVekemansKHoEIs wheezing associated with decreased sleep quality in Sri Lankan children? A questionnaire studyPediatr Pulmonol200742757958317526006

- GoldsteinNAAroninCKantrowitzBThe prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in children with asthma and its behavioral effectsPediatr Pulmonol201550111128113625461921

- GreenfeldMSivanYTaumanRThe effect of seasonality on sleep-disordered breathing severity in childrenSleep Med2013141099199423890953

- GutierrezMJZhuJRodriguez-MartinezCENinoCLNinoGNocturnal phenotypical features of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in asthmatic childrenPediatr Pulmonol20134859260023203921

- LiLXuZJinXSleep-disordered breathing and asthma: evidence from a large multicentric epidemiological study in ChinaRespir Res20151615625958333

- NgDKChanCNgEPNatural history of snoring in Hong Kong adolescentsJ Paediatr Child Health201450859660424943001

- RamagopalMMehtaARobertsDWAsthma as a predictor of obstructive sleep apnea in urban African-American childrenJ Asthma200946989589919905914

- RossKRStorfer-IsserAHartMASleep-disordered breathing is associated with asthma severity in childrenJ Pediatr2012160573674222133422

- ShanleyLLinHFloresGFactors associated with length of stay for pediatric asthma hospitalizationsJ Asthma201552547147725375904

- TengYKChiangLCLueKHPoor sleep quality measured by polysomnography in non-obese asthmatic children with or without moderate to severe obstructive sleep apneaSleep Med20141591062106725018024

- BhattacharjeeRChoiBHGozalDMokhlesiBAssociation of adenotonsillectomy with asthma outcomes in children: a longitudinal database analysisPLoS Med20141111e100175325369282

- BusinoRSQuraishiHAguilaHMontalvoEConnellyPThe impact of adenotonsillectomy on asthma in childrenLaryngoscope2010120Suppl 42007

- Kheirandish-GozalLDayyatEAEidNSMortonRLGozalDObstructive sleep apnea in poorly controlled asthmatic children: effect of adenotonsillectomyPediatr Pulmonol201146991391821465680

- RedlineSTishlerPVSchluchterMAylorJClarkKGrahamGRisk factors for sleep-disordered breathing in children: associations with obesity, race, and respiratory problemsAm J Respir Crit Care Med19991595 Pt 11527153210228121

- LevinJCGagnonLHeXBaumEDKarasDEChuppGLImprovement in asthma control and inflammation in children undergoing adenotonsillectomyPediatr Res201475340340824452590

- AsherMIKeilUAndersonHRInternational study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methodsEur Respir J1995834834917789502

- GozalDShataANakayamaMSpruytKSeasonal variability of sleep-disordered breathing in childrenPediatr Pulmonol201146658158621284096

- MarcusCChapmanDWardSClinical practice guideline: diagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndromePediatrics2002109470471211927718

- MarcusCLBrooksLJDraperKADiagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndromePediatrics2012130357658422926173

- BrockmannPEBertrandPCastro-RodriguezJAInfluence of asthma on sleep disordered breathing in children: a systematic reviewSleep Med Rev201418539339724629825

- GozalDSans CapdevilaOKheirandish-GozalLMetabolic alterations and systemic inflammation in obstructive sleep apnea among nonobese and obese prepubertal childrenAm J Respir Crit Care Med2008177101142114918276939

- MalakasiotiGGourgoulianisKChrousosGKaditisAInteractions of obstructive sleep-disordered breathing with recurrent wheezing or asthma and their effects on sleep qualityPediatr Pulmonol201146111047105421809473

- NayakASA common pathway: asthma and allergic rhinitisAllergy Asthma Proc200223635936512528599

- GozalDPediatric OSA: a case for “united we stand” in the way of a breathPediatr Pulmonol201045121151115220812245

- KalraMLemastersGBernsteinDAtopy as a risk factor for habitual snoring at age 1 yearChest2006129494294616608942

- ArensRMarcusCLPathophysiology of upper airway obstruction: a developmental perspectiveSleep2004275997101915453561

- KaditisAGUrine concentrations of cysteinyl leukotrienes in children with obstructive sleep-disordered breathingChest20091356149619141528

- DayyatESerperoLDKheirandish-GozalLLeukotriene pathways and in vitro adenotonsillar cell proliferation in children with obstructive sleep apneaChest200913551142114919118273

- KaditisAGIoannouMGChaidasKCysteinyl leukotriene receptors are expressed by tonsillar T cells of children with obstructive sleep apneaChest2008134232433118490405

- BrouilletteRTManoukianJJDucharmeFMEfficacy of fluticasone nasal spray for pediatric obstructive sleep apneaJ Pediatr2001138683884411391326

- ZhangLMendoza-SassiRCésarJChadhaNIntranasal corticosteroids for nasal airway obstruction in children with moderate to severe adenoidal hypertrophyCochrane Database Syst Rev2008324

- GoldbartADGoldmanJLVelingMCGozalDLeukotriene modifier therapy for mild sleep-disordered breathing in childrenAm J Respir Crit Care Med2005172336437015879419