Abstract

First described 60 years ago, Castleman disease comprises a rare and heterogeneous cluster of disorders, characterized by lymphadenopathy with unique histological features and associated with cytokine-driven constitutional symptoms and biochemical disturbances. Although unicentric Castleman disease is curable with complete surgical excision, its multicentric counterpart is a considerable therapeutic challenge. The recent development of biological agents, particularly monoclonal antibodies to interleukin-6 and its receptor, allow for more targeted disease-specific intervention that promises improved response rates and more durable disease control; however, further work is required to fill knowledge gaps in terms of underlying pathophysiology and to facilitate alternative treatment options for refractory cases.

Video abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Introduction

Castleman disease (CD), otherwise known as angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia, was first reported in 1954 by Benjamin Castleman, who described a 40-year-old male with a mediastinal mass characterized histologically by lymph node hyperplasia and follicles with small, hyalinized foci.Citation1 Subsequent contributions to the literature have delineated CD as a heterogeneous cluster of disorders, with distinct unicentric CD (UCD) and multicentric CD (MCD) subtypes, and identified the fundamental roles of human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in a significant proportion of cases. These advances have paved the way for the introduction of novel targeted therapies into the CD armamentarium, particularly monoclonal antibodies directed against IL-6 and its receptor. In this paper, we review the current understanding of CD classification and pathophysiology, summarize current and emerging therapeutic strategies, and outline potential avenues for future research.

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of CD is difficult to characterize accurately due to its rarity and clinical heterogeneity. Based on analysis of insurance claims from two American databases, the incidence of CD is estimated at 21–25 cases per million person-years, with 23% of those cases potentially representing MCD.Citation2 The incidence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/HHV-8-associated MCD also appears to be increasing, from 2.3/10,000 patient-years prior to highly active antiretroviral therapy (1983–1996) to 8.3/10,000 patient-years after widespread implementation of highly active antiretroviral therapy (2002–2007).Citation3

Extrapolating from larger case series,Citation4–Citation11 the median age at presentation for UCD is much lower (30–34 years) than for HIV-negative MCD (49–66 years), with HIV-positive MCD falling in between (36–40 years). The sex distribution is approximately equal, though some series have reported a male predominance, generally in the HIV-positive population. Limited data exist regarding geographic variations, though there is a predominance of HIV- and HHV-8-negative MCD in the Polynesian population, with more favorable disease outcome.Citation12 Although other geographic variations likely exist, it is unclear whether these relate mainly to epidemiological characteristics or if patterns of clinical presentation also differ according to location.

Etiology and pathogenesis

Despite notable advances over the past 20 years, the overall understanding of the etiology and pathogenesis of CD remains limited. MCD may be subdivided by HHV-8 status, because all cases of HHV-8-related MCD appear to be a unified clinicopathological entity with consistent clinical features and outcomes, irrespective of HIV status.Citation10 As all HIV-positive MCD cases are strongly associated with HHV-8 infection,Citation6,Citation11,Citation13 the distinct phenomenon of HIV- and HHV-8-negative MCD has been termed “idiopathic MCD”, reflecting the paucity of knowledge regarding its pathophysiology.Citation14 UCD is not typically associated with HIV or HHV-8 infection. Nevertheless, the discovery of the link to HHV-8 and the causal role of IL-6 have provided valuable insights into CD pathophysiology and formed a foundation for development of new treatment strategies and ongoing research.

HHV-8 in MCD and other associated disorders

HHV-8, or Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, is a gamma herpesvirus that was first identified in 1994 from biopsy samples of cutaneous Kaposi’s sarcoma.Citation15 Since that time, it has also been strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related primary effusion lymphoma,Citation16,Citation17 as well as a subset of MCD cases. HHV-8 has the capacity to infect many different cell types, including B-lymphocytes, macrophages, and endothelial cells;Citation18 given that Kaposi’s sarcoma is of endothelial originCitation19 while primary effusion lymphoma and MCD are B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, it is probable that the type of HHV-8-infected cell (as well as the presence or absence of other potential contributory factors, such as HIV coinfection) determines the spectrum of disease that manifests. In MCD, it appears that HHV-8 appears to preferentially infect IgM-positive memory B-cells, inducing their proliferation and differentiation into the characteristic plasmablast phenotype observed.Citation20 To date, it remains uncertain what exactly influences this process in MCD compared to other HHV-8-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, where varying extents of lymphoplasmacytic differentiation are seen.

Akin to other gamma herpesviruses, HHV-8 undergoes latent and lytic phases in its replication cycle – in the latent phase, gene expression is highly restricted, whereas in the lytic phase, gene expression is upregulated and viral replication is enabled.Citation21 In both latent and lytic phases, a recurring theme is the distinctive ability of HHV-8 to produce viral homologs of endogenous human regulatory proteins, facilitating a variety of functions, including viral persistence, inhibition of apoptosis, and cytokine generation.Citation18

The pathogenic contribution of IL-6

One of the earliest links between IL-6 and CD was the demonstration that the site of excess IL-6 production in CD patients was within the germinal centers of involved lymph nodes.Citation22 Following lymph node resection in a patient with UCD, there was a correlation between the reduction in patient symptoms and the fall in serum IL-6, acute phase reactants such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and hypergammaglobulinemia.

Further data supporting this association came from separate experiments involving transgenic mice constitutively expressing murine IL-6Citation23 and viral IL-6 (vIL-6),Citation24 both of which developed an MCD-like syndrome comprising splenomegaly, multifocal lymphadenopathy, hypergammaglobulinemia, and plasmacytosis. However, when the experiment involving vIL-6 was replicated in a murine IL-6 knockout model, the features of MCD did not develop, implying that endogenous IL-6 plays a vital role in the pathogenesis of HHV-8-associated MCD.

The need for endogenous IL-6 may be explained by the greater relative potency of human IL-6 (hIL-6) compared to vIL-6.Citation25 Overproduction of hIL-6 may occur via activation of the nuclear factor kappa B pathway,Citation26 as well as HHV-8 latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA)-mediated upregulation of IL-6 transcription.Citation27 vIL-6 has also been shown to induce hIL-6 production in a variety of cell lines, including those from MCD patients,Citation28 and promotes the secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), resulting in angiogenesis.Citation29 This may contribute to the prominent capillary proliferation that is a histological characteristic of the hyaline vascular subtype of CD. Nevertheless, despite the greater potency of hIL-6, Polizzotto et alCitation30 demonstrated that hIL-6 and vIL-6 can independently or jointly lead to clinical flares of HHV-8-associated MCD. Furthermore, flares were more severe when levels of hIL-6 and vIL-6 were concurrently elevated, suggesting that both human and viral cytokines contribute to disease severity.

The anemia that is commonly seen in MCD appears to be mediated by IL-6-driven hepcidin overproduction, based on a report of anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibody administration to two CD patients with anemia and elevated serum hepcidin levels, which resulted in a rapid decline in hepcidin levels and correction of anemia.Citation31 Anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibody therapy also effectively abolishes CRP production in vivo, establishing it as a convenient marker of IL-6 bioactivity and facilitating monitoring of pharmacodynamic effects.Citation32

Clinical manifestations

The majority of patients with UCD present with isolated lymphadenopathy and may therefore be asymptomatic or have symptoms relating to mass effects on surrounding structures. From a systematic case review including 278 patients with UCD, the mean size of involved lymph nodes at baseline was 5.5 cm, compared to 3.8 cm for MCD cases.Citation33 In this series, the main sites of disease were the chest (29%), neck (23%), abdomen (21%), and retroperitoneum (17%), though other lymph node groups (axillary, inguinal) and the pelvis were also potential sites of involvement.

Systemic symptoms are a common feature of MCD, in keeping with the elevated cytokine levels that are a key driver in its pathogenesis. These include traditional “B” symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and weight loss, as well as generalized lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly. More severe disease phenotypes include a severe, inflammatory vascular leak syndrome where patients may develop ascites, pericardial effusions, pleural effusions, and/or peripheral edema.Citation5 Hematological associations include anemia driven by IL-6 or secondary to autoimmune hemolysis, immune thrombocytopenia,Citation34 and acquired factor VIII deficiency.Citation35 Bronchiolitis obliterans,Citation5 glomerulonephritis,Citation9 and pemphigus have also been reported, with the presence of pemphigus associated with an unfavorable prognosis.Citation9

MCD may be seen in association with the POEMS syndrome, which comprises polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal protein, and skin changes.Citation36 A clinicopathological variant of CD has also recently been reported in Japan, characterized by low-volume lymphadenopathy with CD histology (usually mixed-type or, less commonly, the hyaline vascular variant) in association with thrombocytopenia, ascites, myelofibrosis, renal dysfunction, and organomegaly, termed the TAFRO syndrome.Citation37

Diagnosis

Given the rarity of CD and the typically nonspecific nature of symptoms, a high index of suspicion is required in patients presenting with a compatible clinical picture, such as unifocal or generalized lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and/or unexplained constitutional symptoms. Common laboratory findings include anemia, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia, polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, and elevation of acute phase reactants, such as CRP. Elevations in circulating cytokines such as IL-6 and VEGF may also be detected – although not essential for diagnosis, plasma VEGF levels can be useful in distinguishing and monitoring cases of CD associated with POEMS syndrome.Citation38

Imaging findings are nonspecific and may demonstrate lymphadenopathy and organomegaly, as well as other features of disease, such as sclerotic bony lesions or pulmonary infiltrates. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scanning may have clinical utility in terms of identifying suitable biopsy targets, tracking disease activity, and monitoring response to treatment.Citation39–Citation41

The diagnosis of CD is made on analysis of involved lymph node tissue, showing classic histological features as described. Excisional lymph node biopsy is preferred for diagnosis, particularly if the patient appears to have UCD. Immunohistochemical staining for LANA or polymerase chain reaction testing can be used to detect the presence of HHV-8 within lymph node sections. Detection of plasma HHV-8 viral DNA is not helpful because the test is not specificCitation18 and will be negative in idiopathic cases. Histological confirmation therefore remains essential.

Pathological subtypes

CD is principally distinguished by the presence of localized or generalized lymphadenopathy, designated UCD and MCD, respectively. CD may also be classified according to specific histological features, as well as the presence or absence of viral coinfection.

Histological variants

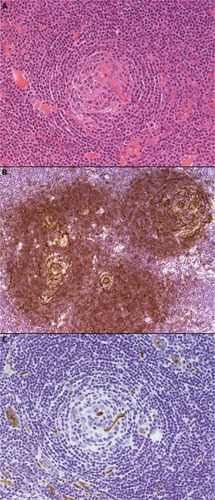

The hyaline vascular variant, which was described in Castleman’s original reports,Citation1,Citation42 usually presents as a unicentric lesion, often thoracic, involving a single lymph node or group of nodes. The histological pattern is usually diagnostic. Typically, there are multiple tight aggregates of follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) or atrophic follicles, often with radially penetrating vessels, contained within expanded circumscribed clusters of mantle zone lymphocytes. The lymphocytes often form concentric “onion skin” layers around the dendritic cells. The vascular pattern between the small lymphoid nodules is also typically prominent, and perivascular hyalinization may be a feature (). FDC atypia or “dysplasia” is not uncommon. There is an association between this form of the disease, various vascular tumors, and dendritic cell proliferations, such as dendritic cell sarcomas.

Figure 1 The hyaline vascular variant of CD.

Notes: Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections (panel A, 200× magnification) demonstrate a vascular, atrophic germinal center with surrounding concentric “onion skin” layers of lymphocytes. Immunohistochemical staining for CD23 (panel B, 200× magnification) highlights several follicular dendritic cell clusters within an expanded mantle zone of CD23-positive cells. CD34 (panel C, 200× magnification) identifies a positively staining blood vessel within an atrophic follicle.

Abbreviation: CD, Castleman disease.

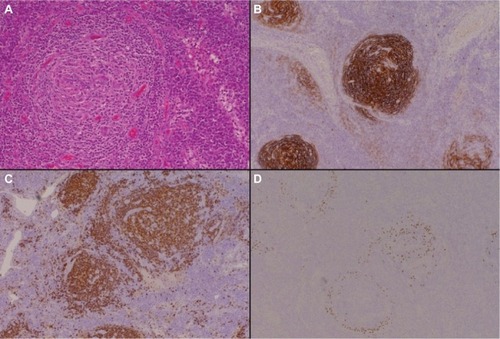

The plasma cell variants of CD (PCCD) are less well-defined histologically, and often the diagnosis is one of exclusion. It is more commonly multicentric than unicentric and is often associated with constitutional symptoms, cytopenias, hypergammaglobulinemia, splenomegaly, and increased IL-6 levels. The lymph nodes usually show preserved architecture, variable follicular hyperplasia, and marked paracortical plasmacytosisCitation43 (). The FDC meshworks are usually preserved, and FDC atypia is not a feature. The vascular pattern is often unremarkable, although a subset of patients may show some hyaline vascular changes (the so-called “mixed” pattern). Unfortunately, the histological features of PCCD may be replicated in a variety of reactive, inflammatory, and infective conditions, including HIV-associated lymphadenopathy and other immunodeficiencies, autoimmune diseases (in particular, rheumatoid arthritis), and IgG4-related lymphadenopathy. Some B-cell lymphomas and plasmacytic tumors may also cause confusion.

Figure 2 The plasma cell variant of CD.

Notes: Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections (panel A, 200× magnification) demonstrate preservation of the lymph node germinal center, with associated paracortical plasmacytosis. Immunohistochemical staining for CD21 (panel B, 100× magnification) highlights the follicular dendritic cells within the germinal centers, while CD20 (panel C, 100× magnification) identifies the normal background B-cell population. Immunoperoxidase staining for HHV-8 (panel D, 100× magnification) reveals HHV-8-positive plasma cells within the expanded mantle zones, which play a key role in the pathogenesis of this CD variant.

Abbreviations: CD, Castleman disease; HHV-8, human herpesvirus-8.

A proportion of the multicentric PCCD cases are associated with HIV infection, and virtually all of these are HHV-8-positive. HHV-8 has also been demonstrated in a significant number of the HIV-negative multicentric PCCD cases. The latter group of patients are often from areas with endemic HHV-8 infection. The term “plasmablastic variant” has been used for these HHV-8-associated cases, identifying the distinctive IgM-positive “plasmablasts” present in the expanded mantle zones in involved lymph nodes. However, the immunophenotype of these cells is not truly plasmablastic, as they may be positive for CD20, and CD138 is often negative. They are usually lambda light chain restricted and positive for HHV-8 antigen, but polyclonal on molecular testing. There is a significant risk of progression of these HHV-8-associated cases to an unusual form of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (WHO designation – large B-cell lymphoma arising in HHV-8-associated MCD). These tumors are also IgM and lambda light chain positive.Citation44,Citation45

Due to the inherent complexities, diagnosing CD (and excluding potential alternative processes) requires careful assessment of clinical, biochemical, radiographic, and histological features. summarizes the different subtypes of CD discussed earlier, as well as notable disease associations and important differential diagnoses that need to be considered, particularly if patients do not respond as anticipated to treatment.

Table 1 Summary of CD subtypes and important differential diagnoses

Overview of current therapeutic strategies and outcomes Unicentric Castleman disease

Complete surgical resection is curative for UCD, leading to excellent long-term outcomes with 10-year overall survival rates in excess of 95%.Citation33 If this is not feasible, the optimal treatment strategy is not well-defined. Debulking surgery should be considered, particularly if there are local symptoms at presentation or if there is a risk of compressing nearby critical structures. Systemic options (as used for MCD, detailed in the “Chemotherapy” section) may also be utilized, potentially facilitating a reduction in lymph node size to an extent, where subsequent resection is possible.Citation46

Although the available literature is confined to a small number of cases,Citation47–Citation58 as summarized in , radiotherapy appears to be a reasonable alternative treatment option in unresectable cases of UCD. Of the 17 identified patients that were treated with radiotherapy alone, the majority received 40–45 Gy (range 27–60), with six patients achieving complete response (CR, 35%) and seven achieving partial response (PR, 41%). After median follow-up of 20 months (range 5–175), three patients (18%) had died, though only one death was disease-related.

Table 2 Summary of radiotherapy outcomes in unresectable UCD

Multicentric Castleman disease

A range of systemic therapies have been utilized in MCD, including cytotoxic chemotherapy, antibodies directed against CD20 as well as IL-6 and its receptor, immunomodulators, bortezomib, and antiviral agents. While they all appear to have disease activity, the literature documenting their use is mainly confined to case reports or small series of patients, limiting overall assessment of efficacy and direct comparisons between regimens.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapeutic options include the following:

Low-dose single-agent chemotherapy, such as daily oral etoposideCitation59 or intermittent etoposide or vinblastineCitation13 – these may facilitate symptom relief, but disease control tends to be lost rapidly after treatment cessation.

Single-agent cladribine is efficaciousCitation60,Citation61 and, from a report of two cases (one idiopathic, one HHV-8-related), can result in complete remission lasting up to 24 months. However, both patients in this report subsequently developed non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which was refractory to salvage chemotherapy.Citation61

Combination chemotherapy, such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) or equivalent,Citation54,Citation62,Citation63 as summarized in . From limited patient numbers (22), these regimens have shown a reasonable rate of CR (eight patients, 36%), with the majority of patients alive (19, 86%) at an overall median follow-up of 38 months. Of note, in the study by Zhu et al,Citation63 all patients were HIV-negative, whereas the other two studies did not report HIV or HHV-8 status.

Table 3 Summary of combination chemotherapy in MCD

Rituximab

Rituximab, a humanized monoclonal antibody to CD20 (which is typically found on CD plasmablasts), has shown significant activity in HIV-positive and idiopathic MCD patients, when used either as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy. The strongest evidence to support its use is in the HIV-positive population, with single-agent rituximab achieving sustained remissions in the majority of patients (treated with four infusions of 375 mg/m2 at weekly intervals) from two Phase II studies. In the first study of 24 patients by Gérard et al,Citation64 the overall survival rate was 92% at 1 year, with 71% in ongoing remission. In the second study of 21 patients by Bower et al,Citation65 the overall survival rate was 95% at 2 years, with 79% in ongoing remission. Toxicity was mild in both groups, with reactivation of Kaposi’s sarcoma being the major adverse effect. A small study of three patients also demonstrated the efficacy of rituximab monotherapy in the idiopathic MCD cohort, with two patients achieving durable PR (with 16 and 40 months of follow-up) and the last patient having a significant decrease in inflammatory markers, maintained for over 10 months with subsequent chemotherapy.Citation66

Rituximab has also been combined with chemotherapy in the HIV-positive population, with the largest patient numbers receiving rituximab with intravenous etoposide or liposomal doxorubicin. In the first study of 14 patients by Bower et alCitation6 (rituximab and etoposide), the overall survival rate was 86% at 2 years, compared to 97% in their rituximab monotherapy cohort. In the second study of 17 patients by Uldrick et alCitation67 (rituximab and liposomal doxorubicin), the overall survival rate was 81% at 3 years, with 69% in ongoing remission.

From retrospective analyses, patients who received rituximab-containing regimens achieved superior CR rates and overall survival compared to patients who received nonrituximab-containing regimens,Citation68,Citation69 as well as a reduced risk of developing subsequent non-Hodgkin lymphoma.Citation69 Rituximab also had significant efficacy in the retreatment of relapsed HIV-associated MCD,Citation68 though the patient numbers in this subgroup were small. These data support the use of rituximab in MCD cases where anti-IL-6 therapy is not available; however, larger patient numbers and more mature follow-up data are required to ascertain if addition of chemotherapy improves outcomes compared to rituximab monotherapy.

Antiviral agents

Limited trials of antiviral agents in HIV- and HHV-8-associated MCD have been undertaken. One study by Uldrick et alCitation70 utilized high-dose zidovudine and valganciclovir in 14 patients, with 86% achieving major clinical response (defined as 50% or greater reduction in signs and symptoms) and 50% achieving major biochemical response (50% or greater improvement in disease-associated laboratory abnormalities). The median progression-free survival was 6 months, and the major toxicities were hematological, with five patients developing Grade 4 anemia and four patients developing Grade 4 neutropenia.

Ganciclovir has also been shown to induce clinical and virologic improvement in three patients, though one patient died from overwhelming fungal infection shortly after commencement and another patient had only short-term benefit.Citation71 Cidofovir, another antiviral agent active against HHV-8, did not have meaningful effect in MCD.Citation72

Based on these studies, it remains unclear how best to incorporate antiviral agents into MCD therapy. While hematological toxicity may prohibit the combination of high-dose zidovudine and valganciclovir, valganciclovir or ganciclovir could be combined with rituximab and/or chemotherapy, or used as maintenance therapy after more effective upfront regimens.

Other

Corticosteroids may offer effective symptom relief but, as the duration of response is typically limited, their main role is in combination with chemotherapy (such as CHOP) or other MCD treatments. Case reports and small series of interferon α,Citation73–Citation75 thalidomide,Citation76–Citation79 lenalidomide,Citation80 bortezomib,Citation81–Citation85 and autologous stem cell transplantationCitation86–Citation88 have also been published (), providing grounds for larger trials of these therapies as well as supporting their potential use as salvage options in relapsed, refractory disease.

Table 4 Summary of immunomodulatory drugs and autologous stem cell transplantation in MCD

Emerging use of biologics

Anti-IL-6 therapy

The advent of monoclonal antibody therapy targeting the IL-6 pathway has significantly impacted the treatment of patients with idiopathic MCD. Agents that have been studied include siltuximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody to IL-6, and tocilizumab, a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks the IL-6 receptor (). Siltuximab has regulatory approval in the USA and Europe for the treatment of HIV-negative and HHV-8-negative MCD, while tocilizumab has approval for use in Japan. Access to these therapies is currently obtained through clinical use agreements in their respective countries.

Table 5 Summary of clinical trials and case series for siltuximab and tocilizumab in MCD

Siltuximab

Siltuximab is a chimeric (human/murine) IgG1 monoclonal antibody that complexes with IL-6 and prevents it from binding to both soluble and membrane-bound IL-6 receptors. In the initial Phase I study by Kurzrock et al,Citation89 siltuximab was trialed in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and idiopathic MCD, with escalating dose cohorts ranging from 3 to 12 mg/kg every 2 weeks. A total of 37 MCD patients were enrolled, with 32 patients (86%) deriving clinical benefit response, defined as improvement (and no worsening of the remaining categories) in anemia, fatigue, fever or night sweats, increase in weight, and reduction of lymphadenopathy. Overall survival was 92% during a median follow-up period of 2.4 years.

In the follow-up Phase II randomized multicenter study by van Rhee et al,Citation90 79 idiopathic MCD patients were randomized in a 2:1 fashion to siltuximab (11 mg/kg every 3 weeks) or placebo. The primary endpoint was durable tumor and symptomatic response, defined as a complete or partial nodal response, as well as stabilization of disease-related symptoms for at least 18 weeks. A total of 18 patients (34% – 1 CR, 17 PR) in the siltuximab arm achieved the primary endpoint, compared to 0% receiving placebo. Furthermore, 30 patients (57%) had a durable symptomatic response, compared to five patients (19%) in the placebo arm. The 1-year survival rate was 100% in the siltuximab group and 92% in the placebo group. In the extension study,Citation91 all 19 patients continued to receive siltuximab for up to 7 years, without evidence of cumulative toxicity or treatment discontinuation.

Siltuximab appears to be well-tolerated, with no dose-limiting toxicities observed in its Phase I study. In the Phase II study, pruritus was the most common adverse event (42%), followed by upper respiratory tract infection (36%), fatigue (34%), maculopapular rash (34%), and peripheral edema (32%). Infusion reactions occurred in 8% of patients, with one being Grade 3 in severity (anaphylactic). Only one episode of sepsis was reported, which is notable given that patients on anti-IL-6 therapy may have delayed presentation with infection due to suppression of typical clinical features mediated by IL-6, such as fever or elevated inflammatory markers like CRP.Citation32 No treatment-related deaths occurred.

Tocilizumab

Unlike siltuximab, tocilizumab is a recombinant humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that attaches to soluble and membrane-bound IL-6 receptors, blocking IL-6 binding and downstream intracellular signaling. The major multicenter, open-label study of tocilizumab enrolled 28 patients, of whom 26 had idiopathic MCD and two were HIV-negative but positive for HHV-8.Citation92 All patients received 8 mg/kg of tocilizumab for 16 weeks, after which doses varied according to investigator discretion as part of a study extension. Tocilizumab therapy resulted in significant reduction in lymphadenopathy (30% reduction in the mean short axis of involved lymph nodes) for 52% of patients after 1 year of treatment. Marked improvement was also seen in biochemical measures such as CRP and fibrinogen in 64% and 71% of patients, respectively. Most patients (27, 96%) received tocilizumab for over 3 years, without evidence of disease progression.

Major reported adverse effects of tocilizumab from the previous study included upper respiratory tract infections (57%), pruritus (21%), malaise (21%), pharyngitis (18%), and diarrhea (18%). Fourteen patients (50%) experienced infusion reactions, though all were transient and mild. Two patients required admission for cellulitis, but no other serious infections were noted.

Two small case series of tocilizumab in MCD have also been published, with a total of five patients achieving 100% response rates in follow-up ranging up to 3 years.Citation93,Citation94 Single case reports have also suggested efficacy of tocilizumab on potential associated manifestations of MCD, including cardiomyopathy,Citation95 autoimmune hemolytic anemia,Citation96 uveitis,Citation97 and cardiac amyloidosis,Citation98 though these findings require confirmation. However, when used in two patients with HIV-and HHV-8-associated MCD, the response to tocilizumab was very short-lived, implying that IL-6 receptor blockade alone may be inadequate in this subpopulation, and that further studies in this subpopulation are clearly required.Citation99

Anakinra

Anakinra, a recombinant interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor antagonist, has theoretical benefit in MCD based on the ability of IL-1 to stimulate IL-6 production and the use of both IL-1 and IL-6 antagonists in the treatment of inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis. Use of anakinra in MCD remains anecdotal and confined to two case reports, though both patients did achieve dramatic clinical and biochemical responses.Citation100,Citation101

Long-term outcome

The prognosis of CD is variable and depends predominantly on disease subtype. As previously mentioned, patients with UCD enjoy excellent long-term outcomes if complete resection can be achieved, with 10-year overall survival rates greater than 95%.Citation33 Even in unresectable UCD cases, radiotherapy may offer good long-term response rates (82% overall survival at 20 months), though supporting data is limited. The HIV- and HHV-8-associated subtype of MCD has the worst prognosis, with the majority of patients in early studies dying within 2 years of diagnosis.Citation7,Citation44,Citation102 Introduction of rituximab appears to have ameliorated these outcomes somewhat, with 2-year overall survival in rituximab-treated cases improving to 94% in a larger case series.Citation6 Finally, although there is a paucity of survival data for the idiopathic MCD cohort prior to anti-IL-6 therapy, a systematic literature review identified a 3-year disease-free survival rate of 45.7% in HIV-negative patients (though HHV-8 status is unknown).Citation4 The high rates of durable response seen in the early siltuximab and tocilizumab studies provide considerable promise for idiopathic MCD patients, though larger studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Conclusion and future directions

In the 60 years since Castleman’s initial report, substantial advances have been made in terms of characterizing the pathophysiology of CD, defining distinct clinicopathological subtypes and developing more effective, targeted treatment strategies. However, in some respects, these revelations raise more questions than answers – particularly in MCD, where much is known about the pathophysiology of HIV- and HHV-8-associated cases, but treatment options remain limited. Conversely, the emerging use of biologic therapies (including monoclonal antibodies targeting the IL-6 pathway) has great potential in treating HIV- and HHV-8-negative cases, but the underlying disease mechanisms in this subgroup are still poorly understood.

Given the rarity and heterogeneity of CD, a high index of clinical suspicion, consistent case definition, and international collaboration – through organizations like the Castleman Disease Collaborative NetworkCitation103 – will be integral factors in facilitating ongoing discoveries for this fascinating disease, hopefully translating into continued improvements in patient care and more favorable survival outcomes.

Disclosure

SJH has received funding from Janssen-Cilag for the conduct of clinical trials and participation in advisory boards in relation to Castleman disease. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Case records of the Massachusetts general hospital weekly clinicopathological exercises: case 40011N Engl J Med19542501263013111435

- MunshiNMehraMvan de VeldeHDesaiAPotluriRVermeulenJUse of a claims database to characterize and estimate the incidence rate for Castleman diseaseLeuk Lymphoma20155651252126025120049

- PowlesTStebbingJBazeosAThe role of immune suppression and HHV-8 in the increasing incidence of HIV-associated multicentric Castleman’s diseaseAnn Oncol200920477577919179554

- TalatNSchulteKMCastleman’s disease: systematic analysis of 416 patients from the literatureOncologist20111691316132421765191

- DispenzieriAArmitageJOLoeMJThe clinical spectrum of Castleman’s diseaseAm J Hematol20128711997100222791417

- BowerMNewsom-DavisTNareshKClinical features and outcome in HIV-associated multicentric Castleman’s diseaseJ Clin Oncol201129182481248621555697

- OksenhendlerEDuarteMSoulierJMulticentric Castleman’s disease in HIV infection: a clinical and pathological study of 20 patientsAIDS199610161678924253

- RobinsonDReynoldsMCasperCClinical epidemiology and treatment patterns of patients with multicentric Castleman disease: results from two US treatment centresBr J Haematol20141651394824387011

- DongYWangMNongLClinical and laboratory characterization of 114 cases of Castleman disease patients from a single centre: paraneoplastic pemphigus is an unfavourable prognostic factorBr J Haematol2015169683484225824806

- DossierAMeigninVFieschiCBoutboulDOksenhendlerEGalicierLHuman herpesvirus 8-related Castleman disease in the absence of HIV infectionClin Infect Dis201356683384223223599

- SoulierJGrolletLOksenhendlerEKaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman’s diseaseBlood1995864127612807632932

- ZhaiSSimpsonDPolynesian variant of idiopathic multicentric Castleman diseaseBlood2013122215127

- OksenhendlerECarcelainGAokiYHigh levels of human herpesvirus 8 viral load, human interleukin-6, interleukin-10, and C reactive protein correlate with exacerbation of multicentric Castleman disease in HIV-infected patientsBlood20009662069207310979949

- FajgenbaumDCvan RheeFNabelCSHHV-8-negative, idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease: novel insights into biology, pathogenesis, and therapyBlood2014123192924293324622327

- ChangYCesarmanEPessinMSIdentification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcomaScience19942665192186518697997879

- CesarmanEChangYMoorePSSaidJWKnowlesDMKaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomasN Engl J Med199533218118611917700311

- NadorRGCesarmanEChadburnAPrimary effusion lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity associated with the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpes virusBlood19968826456568695812

- BhutaniMPolizzottoMNUldrickTSYarchoanRKaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-associated malignancies: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and advances in treatmentSemin Oncol201542222324625843728

- FloreORafiiSElySO’LearyJJHyjekEMCesarmanETransformation of primary human endothelial cells by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirusNature199839466935885929707121

- HassmanLMEllisonTJKedesDHKSHV infects a subset of human tonsillar B cells, driving proliferation and plasmablast differentiationJ Clin Invest2011121275276821245574

- GanemDKSHV infection and the pathogenesis of Kaposi’s sarcomaAnnu Rev Pathol2006127329618039116

- YoshizakiKMatsudaTNishimotoNPathogenic significance of interleukin-6 (IL-6/BSF-2) in Castleman’s diseaseBlood1989744136013672788466

- BrandtSJBodineDMDunbarCENienhuisAWDysregulated interleukin 6 expression produces a syndrome resembling Castleman’s disease in miceJ Clin Invest19908625925992384605

- SuthausJStuhlmann-LaeiszCTompkinsVSHHV-8-encoded viral IL-6 collaborates with mouse IL-6 in the development of multicentric Castleman disease in miceBlood2012119225173518122490805

- BurgerRNeipelFFleckensteinBHuman herpesvirus type 8 interleukin-6 homologue is functionally active on human myeloma cellsBlood1998916185818639490667

- SchwarzMMurphyPMKaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor constitutively activates NF-kappa B and induces proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine production via a C-terminal signaling determinantJ Immunol2001167150551311418689

- AnJLichtensteinAKBrentGRettigMBThe Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) induces cellular interleukin 6 expression: role of the KSHV latency-associated nuclear antigen and the AP1 response elementBlood200299264965411781250

- MoriYNishimotoNOhnoMHuman herpesvirus 8-encoded interleukin-6 homologue (viral IL-6) induces endogenous human IL-6 secretionJ Med Virol200061333233510861641

- AokiYJaffeESChangYAngiogenesis and hematopoiesis induced by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded interleukin-6Blood199993124034404310361100

- PolizzottoMNUldrickTSWangVHuman and viral interleukin-6 and other cytokines in Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-associated multicentric Castleman diseaseBlood2013122264189419824174627

- KawabataHTomosugiNKandaJTanakaYYoshizakiKUchiyamaTAnti-interleukin 6 receptor antibody tocilizumab reduces the level of serum hepcidin in patients with multicentric Castleman’s diseaseHaematologica200792685785817550864

- RossiJFLuZYJourdanMKleinBInterleukin-6 as a therapeutic targetClin Cancer Res20152161248125725589616

- TalatNBelgaumkarAPSchulteKMSurgery in Castleman’s disease: a systematic review of 404 published casesAnn Surg2012255467768422367441

- MarshJHColbournDSDonovanVStaszewskiHSystemic Castleman’s disease in association with Evan’s syndrome and vitiligoMed Pediatr Oncol19901821691722304424

- MariettaMPozziSLuppiMAcquired haemophilia in HIV negative, HHV-8 positive multicentric Castleman’s disease: a case reportEur J Haematol200370318118212605662

- DispenzieriAKyleRALacyMQPOEMS syndrome: definitions and long-term outcomeBlood200310172496250612456500

- KawabataHTakaiKKojimaMCastleman–Kojima disease (TAFRO syndrome): a novel systemic inflammatory disease characterized by a constellation of symptoms, namely, thrombocytopenia, ascites (anasarca), microcytic anemia, myelofibrosis, renal dysfunction, and organomegaly: a status report and summary of Fukushima (6 June, 2012) and Nagoya meetings (22 September, 2012)J Clin Exp Hematop2013531576123801135

- D’SouzaAHaymanSRBuadiFThe utility of plasma vascular endothelial growth factor levels in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with POEMS syndromeBlood2011118174663466521881050

- RobinsonHPrinceHMRamdaveSSeymourJFElliottPHicksRPreliminary experience of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in Castleman’s diseaseLeuk Lymphoma200647122664266617169817

- BarkerRKazmiFStebbingJFDG-PET/CT imaging in the management of HIV-associated multicentric Castleman’s diseaseEur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging200936464865219050873

- PolizzottoMNMilloCUldrickTS18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-associated multicentric Castleman disease: correlation with activity, severity, inflammatory and virologic parametersJ Infect Dis201521281250126025828248

- CastlemanBIversonLMenendezVPLocalized mediastinal lymphnode hyperplasia resembling thymomaCancer19569482283013356266

- KellerARHochholzerLCastlemanBHyaline-vascular and plasma-cell types of giant lymph node hyperplasia of the mediastinum and other locationsCancer19722936706834551306

- DupinNDissTLKellamPHHV-8 is associated with a plasmablastic variant of Castleman disease that is linked to HHV-8-positive plasmablastic lymphomaBlood20009541406141210666218

- CroninDMWarnkeRACastleman disease: an update on classification and the spectrum of associated lesionsAdv Anat Pathol200916423624619546611

- BanderaBAinsworthCShikleJRupardERoachMTreatment of unicentric Castleman disease with neoadjuvant rituximabChest201013851239124121051400

- FitzpatrickPJBrownTCAngiofollicular lymph node hyperplasiaCan Med Assoc J19689925125912625700853

- NordstromDGTewfikHHLatouretteHBPlasma cell giant lymph node hyperplasia responding to radiation therapyAJR Am J Roentgenol19781301169171413407

- StokesSHGriffithRCThomasPRAngiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia (Castleman’s disease) associated with vertebral destructionCancer19855648768794016679

- WeisenburgerDDDeGowinRLGibsonPArmitageJORemission of giant lymph node hyperplasia with anemia after radiotherapyCancer1979442457462476562

- MasseyGVKornsteinMJWahlDHuangXLMcCradyCWCarchmanRAAngiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia (Castleman’s disease) in an adolescent female. Clinical and immunologic findingsCancer1991686136513721873789

- VeldhuisGJvan der LeestAHde WolfJTde VriesEGVellengaEA case of localized Castleman’s disease with systemic involvement: treatment and pathogenetic aspectsAnn Hematol199673147508695726

- BowneWBLewisJJFilippaDAThe management of unicentric and multicentric Castleman’s disease: a report of 16 cases and a review of the literatureCancer199985370671710091744

- ChronowskiGMHaCSWilderRBCabanillasFManningJCoxJDTreatment of unicentric and multicentric Castleman disease and the role of radiotherapyCancer200192367067611505414

- NeuhofDDebusJOutcome and late complications of radiotherapy in patients with unicentric Castleman diseaseActa Oncol20064581126113117118850

- LiYMLiuPHZhangYHRadiotherapy of unicentric mediastinal Castleman’s diseaseChin J Cancer201130535135621527068

- MatthiesenCRamgopolRSeaveyJAhmadSHermanTIntensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) for the treatment of unicentric Castlemans disease: a case report and review of the use of radiotherapy in the literatureRadiol Oncol201246326527023077466

- MirandaFAFariaVHArrudaGVSilvaLGRadiation therapy in the treatment of unicentric Castleman’s diseaseJ Bras Pneumol201339111611823503497

- ScottDCabralLHarringtonWJTreatment of HIV-associated multicentric Castleman’s disease with oral etoposideAm J Hematol200166214815011421297

- BordeleauLBredesonCMarkmanS2-Chloro-deoxyadenosine therapy for giant lymph node hyperplasiaBr J Haematol19959136686708555073

- ColleoniGWDuarteLCKerbauyFR2-Chloro-deoxyadenosine induces durable complete remission in Castleman’s disease but may accelerate its transformation to non-Hodgkin’s lymphomaActa Oncol200342778478714690166

- HerradaJCabanillasFRiceLManningJPughWThe clinical behavior of localized and multicentric Castleman diseaseAnn Intern Med199812886576629537940

- ZhuSHYuYHZhangYSunJJHanDLLiJClinical features and outcome of patients with HIV-negative multicentric Castleman’s disease treated with combination chemotherapy: a report on 10 patientsMed Oncol201330149223400962

- GérardLBéreznéAGalicierLProspective study of rituximab in chemotherapy-dependent human immunodeficiency virus associated multicentric Castleman’s disease: ANRS 117 CastlemaB TrialJ Clin Oncol200725223350335617664482

- BowerMPowlesTWilliamsSBrief communication: rituximab in HIV-associated multicentric Castleman diseaseAnn Intern Med20071471283683918087054

- IdeMKawachiYIzumiYKasagiKOginoTLong-term remission in HIV-negative patients with multicentric Castleman’s disease using rituximabEur J Haematol200676211912316405432

- UldrickTSPolizzottoMNAlemanKRituximab plus liposomal doxorubicin in HIV-infected patients with KSHV-associated multicentric Castleman diseaseBlood2014124243544355225331113

- HoffmannCSchmidHMüllerMImproved outcome with rituximab in patients with HIV-associated multicentric Castleman diseaseBlood2011118133499350321778341

- GérardLMichotJMBurcheriSRituximab decreases the risk of lymphoma in patients with HIV-associated multicentric Castleman diseaseBlood2012119102228223322223822

- UldrickTSPolizzottoMNAlemanKHigh-dose zidovudine plus valganciclovir for Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-associated multicentric Castleman disease: a pilot study of virus-activated cytotoxic therapyBlood2011117266977698621487108

- CasperCNicholsWGHuangMLCoreyLWaldARemission of HHV-8 and HIV-associated multicentric Castleman disease with ganciclovir treatmentBlood200410351632163414615380

- BerezneAAgbalikaFOksenhendlerEFailure of cidofovir in HIV-associated multicentric Castleman diseaseBlood20041031143684369 author reply 436915155471

- TamayoMGonzalezCMajadoMJCandelRRamosJLong-term complete remission after interferon treatment in a case of multicentric Castelman’s diseaseAm J Hematol19954943593607639289

- KumariPSchechterGPSainiNBenatorDASuccessful treatment of human immunodeficiency virus-related Castleman’s disease with interferon-alphaClin Infect Dis200031260260410987728

- AndrèsEMaloiselFInterferon-alpha as first-line therapy for treatment of multicentric Castleman’s diseaseAnn Oncol200011121613161411205472

- LeeFCMerchantSHAlleviation of systemic manifestations of multicentric Castleman’s disease by thalidomideAm J Hematol2003731485312701121

- JungCPEmmerichBGoebelFDBognerJRSuccessful treatment of a patient with HIV-associated multicentric Castleman disease (MCD) with thalidomideAm J Hematol200475317617714978701

- StaryGKohrgruberNHernethAMGaigerAStinglGRiegerAComplete regression of HIV-associated multicentric Castleman disease treated with rituximab and thalidomideAIDS200822101232123418525273

- RamasamyKGandhiSTenant-FlowersMRituximab and thalidomide combination therapy for Castleman diseaseBr J Haematol2012158342142322583139

- SzturzPAdamZChovancováJLenalidomide: a new treatment option for Castleman diseaseLeuk Lymphoma201253102089209121902577

- YuanZGDunXYLiYHHouJTreatment of multicentric Castleman’s disease accompanying multiple myeloma with bortezomib: a case reportJ Hematol Oncol200921919400935

- SobasMAAlonso VenceNDiaz AriasJBendaña LopezAFraga RodriguezMBello LopezJLEfficacy of bortezomib in refractory form of multicentric Castleman disease associated to poems syndrome (MCD-POEMS variant)Ann Hematol201089221721919636554

- SbengheMMBesaEMahipalADulau FloreaABrayPCaroJHHV-8-associated multicentric Castleman’s disease in HIV-negative patient: a novel therapy for an orphan diseaseOncologist2012171145146 author reply 147–14822286773

- KhanAASirajFBhargavaMAggarwalSSuccessful treatment of multicentric Castleman’s disease accompanying myeloma with bortezomibBMJ Case Rep20122012 pii:bcr2012007646

- LinQFangBHuangHEfficacy of bortezomib and thalidomide in the recrudescent form of multicentric mixed-type Castleman’s diseaseBlood Cancer J20155e29825794134

- RepettoLJaiprakashMPSelbyPJGustersonBAWilliamsHJMcElwainTJAggressive angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia (Castleman’s disease) treated with high dose melphalan and autologous bone marrow transplantationHematol Oncol1986432132173533746

- GantiAKPipinosICulceaEArmitageJOTarantoloSSuccessful hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in multicentric Castleman disease complicated by POEMS syndromeAm J Hematol200579320621015981232

- TalYHaberGCohenMJAutologous stem cell transplantation in a rare multicentric Castleman disease of the plasma cell variantInt J Hematol201193567768021437636

- KurzrockRVoorheesPMCasperCA phase I, open-label study of siltuximab, an anti-IL-6 monoclonal antibody, in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, or Castleman diseaseClin Cancer Res201319133659367023659971

- van RheeFWongRSMunshiNSiltuximab for multicentric Castleman’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trialLancet Oncol201415996697425042199

- van RheeFCasperCVoorheesPMA Phase 2, open-label, multicenter study of the long-term safety of siltuximab (an anti-interleukin-6 monoclonal antibody) in patients with multicentric Castleman diseaseOncotarget2015630304083041926327301

- NishimotoNKanakuraYAozasaKHumanized anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody treatment of multicentric Castleman diseaseBlood200510682627263215998837

- MatsuyamaMSuzukiTTsuboiHAnti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody (tocilizumab) treatment of multicentric Castleman’s diseaseIntern Med2007461177177417541233

- GaleottiCBoucheronAGuillaumeSKoné-PautISustained remission of multicentric Castleman disease in children treated with tocilizumab, an anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibodyMol Cancer Ther20121181623162622638145

- KandaJKawabataHYamajiYReversible cardiomyopathy associated with Multicentric Castleman disease: successful treatment with tocilizumab, an anti-interleukin 6 receptor antibodyInt J Hematol200785320721117483056

- YuzurihaASaitohTKoisoHSuccessful treatment of autoimmune hemolytic anemia associated with multicentric Castleman disease by anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody (tocilizumab) therapyActa Haematol2011126314715021757886

- OshitariTKajitaFTobeARefractory uveitis in patient with castleman disease successfully treated with tocilizumabCase Rep Ophthalmol Med2012201296818023198204

- ShirakawaKEgashiraTIedaMMultidisciplinary approach to the treatment of cardiac AA amyloidosis and aortic stenosis due to Castleman’s disease: a hybrid therapy with tocilizumab and aortic valve replacementInt J Cardiol20141732e9e1124681024

- NagaoANakazawaSHanabusaHShort-term efficacy of the IL6 receptor antibody tocilizumab in patients with HIV-associated multicentric Castleman disease: report of two casesJ Hematol Oncol201471024438824

- GaleottiCTranTAFranchi-AbellaSFabreMParienteDKoné-PautIIL-1RA agonist (anakinra) in the treatment of multifocal castleman disease: case reportJ Pediatr Hematol Oncol2008301292092419131781

- El-OstaHJankuFKurzrockRSuccessful treatment of Castleman’s disease with interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (Anakinra)Mol Cancer Ther2010961485148820501803

- ZietzCBognerJRGoebelFDLöhrsUAn unusual cluster of cases of Castleman’s disease during highly active antiretroviral therapy for AIDSN Engl J Med1999340241923192410375310

- NewmanSKJayanthanRKMitchellGWTaking control of Castleman disease: leveraging precision medicine technologies to accelerate rare disease researchYale J Biol Med201588438338826604862