Abstract

Hemophilia is a bleeding disorder caused by a congenital abnormality of blood coagulation. Until the mid-1970s, patients with hemophilia (PWH) were advised to refrain from physical activity (PA) because of a perceived increased risk of bleeding. Since then, PA, which is recognized as being essential for health maintenance, is now recommended by the World Federation of Hemophilia. Moreover, a number of studies reported that PA can improve treatment efficacy and prevent bleeding in PWH. Physical assessment and intervention in PA are currently used in clinical practice. However, the necessity of PA is not emphasized, and many PWH generally have low- to- no PA. Therefore, a behavior change approach to encourage patient motivation is becoming ever more important. In this article, we review articles addressing PA in PWH and discuss strategies to encourage PA through a behavior change approach by focusing on factors relevant to hemophilia, such as benefits and bleeding risk of PA, risk management of bleeding, PA characteristics, and difficulty with exercise adherence. The trust relationship between clinicians and patients, a transtheoretical model of behavior change, and motivation theory as approaches to promote PA are introduced. Finally, we review a case report of the clinical success of a behavior change approach to promote PA. Many PWH find it difficult to continue PA because of aging, fear of bleeding, insufficient recognition of PA benefits, and psychological problems. Therefore, it is essential and important to perform prophylaxis with PWH and to heighten their understanding of the benefits and risks of PA, before initiating the exercise regimen. For those patients who find it difficult to participate in PA, it is necessary to plan individual-based behavior change approach and encourage self-efficacy.

Introduction

Hemophilia

Hemophilia is an inherited X-linked recessive bleeding disorder, which is caused by a deficiency of coagulation factor VIII (hemophilia A) or factor IX (hemophilia B) related to mutations of the clotting factor gene; it mainly affects males and is subcategorized as severe, moderate, or mild. A definitive diagnosis depends on a factor assay to demonstrate the deficiency of FVIII or FIX. Severity classification of hemophilia is based on the factor activity, which is as follows: severe (<1 IU/dL [<0.01 IU/mL] or <1% of normal), moderate (1–5 IU/dL [0.01–0.05 IU/mL] or 1%–5% of normal), and mild (5–40 IU/dL [0.05–0.40 IU/mL] or 5% to <40% of normal).Citation1 People with severe hemophilia usually bleed frequently into their muscles or joints. Bleeding is often spontaneous, which means it happens for no obvious reason. People with moderate hemophilia bleed less frequently. They may bleed for a long time after a surgery, bad injury, or dental work. A person with moderate hemophilia will rarely experience spontaneous bleeding. People with mild hemophilia usually bleed only as a result of surgery or major injury.Citation1

Particular joints that have recurrent bleeding are usually referred to as “target joints.” A target joint can progress to synovitis and arthropathy if bleeding is not controlled. Clotting factor replacement therapy is the first-choice treatment for hemophilia. A major complication in hemophilia is hemophilic arthropathy caused by repeated intra-articular bleeding, which accounts for 65%–80% of all bleeding episodes with ~80% predominantly localized to the elbows, ankles, and knees.Citation2

Factor replacement therapy is mainly classified into prophylaxis therapy and episodic “on-demand” therapy. Prophylaxis is the treatment by intravenous injection of a factor concentrate a few times per week to prevent anticipated bleeding. The purpose is to maintain normal musculoskeletal functions by preventing bleeding and joint destruction. The effects have been reported particularly in patients with severe and moderate hemophilia.Citation1 The prophylaxis protocol is 15–40 IU/kg per dose administered three times a week for those with hemophilia A, and twice a week for those with hemophilia B.Citation1 Prophylaxis is recommended to prevent complications of joint dysfunction. It was reported that the frequency of intra-articular bleeding and dysfunction of bone and cartilage in boys who underwent prophylaxis were significantly lower than those in boys who underwent on-demand therapy.Citation3 However, some patients have a factor VIII or IX alloantibody inhibitor, which should be considered if there is less than expected factor VIII or IX activity after clotting factor replacement therapy.Citation4 A low-responding inhibitor is defined as an inhibitor level that is persistently <5 BU/mL, whereas a high-responding inhibitor is defined by a level ≥5 BU/mL.Citation1 Patients with a history of a high-responding inhibitor may have joint dysfunction.Citation5 Therefore, an assessment of past inhibitor titer is important. Hemostatic treatment for such patients is more difficult and requires a greater dose of coagulation factor or bypassing agents because of inhibition due to neutralization of clotting factors.Citation1 Patients with a low-responding inhibitor may be treated with specific factor replacement at a much higher dose, if possible, to neutralize the inhibitor with excess factor activity and stop bleeding.Citation1 On the other hand, bypass therapy using activated prothrombin complex concentrate or recombinant activated factor VII is performed for patients with a high-responding inhibitor.Citation1

Prophylaxis is advisable prior to engaging in activities with a higher risk of injury. Therefore, prophylaxis or preliminary replacement therapy is essential before physical activity (PA). Preliminary replacement therapy and prophylaxis are sometimes used together depending on the bleeding risk. Prior to PA, prophylaxis is performed based on the coagulation factor activity levels. Adequate levels of clotting factors are required; a level of >5% is standard for a normal level of daily activity, whereas a factor level of >15% is recommended prior to sports activities.Citation6 In addition, a factor level of 20%–40% is recommended prior to physiotherapy (PT).Citation7 It is recommended to perform PT on the day prophylaxis is performed. The recommended dose prior to PA and PT has not been reported for patients with inhibitors. However, it is recommended to perform PA on the day bypass therapy or neutralization is performed. Therefore, close cooperation with pediatricians and physicians and a check on the coagulation system test values are essential.

Need for PA in patients with hemophilia

Until the mid-1970s, patients with hemophilia (PWH) were advised to refrain from PA because of a perceived increased risk of bleeding.Citation2,Citation8,Citation9 However, such recommendations may lead to physical dysfunction and obesity among PWH.Citation10–Citation12 Since then, PA, which is recognized as being essential for health maintenance,Citation2,Citation8,Citation13 is now recommended by the World Federation of Hemophilia.Citation1 Many studies reported that PA can improve treatment efficacy and prevent bleeding in PWH.Citation2,Citation8,Citation14 Young PWH are now able to enjoy PA in daily life without restriction.Citation2 Furthermore, PWH often survive to an advanced age.Citation15–Citation17 For elderly PWH, physical inactivity may increase the risk of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and osteoporosis and related fractures, in addition to hemophilia-related complications.

Need for behavior change approach

It is reported that 50% of the general population discontinued participation in PA regimens based on the traditional scientific approaches to achieve fitness after 3–6 months.Citation18 Therefore, the effectiveness of behavior change approaches to continue and encourage PA has been investigated. The behavior change approach is an interventional method to identify factors related to PA based on behavior science theory with the aim to realize a physically active lifestyle. Therefore, we conducted a literature review of articles addressing PA in PWH and discuss strategies to encourage PA through a behavior change approach by focusing on factors relevant to hemophilia, such as benefits and bleeding risk of PA, risk management of bleeding, PA characteristics, and difficulty with exercise adherence.

PA and hemophilia

General benefits of PA

According to the “Global Recommendations on PA for Health” by the World Health Organization (WHO), physical inactivity is the fourth leading risk factor for mortality, accounting for 6% of deaths globally, following hypertension (13%), smoking (9%), and high blood glucose (6%).Citation19 Health problems associated with physical inactivity are more severe for PWH than the general population. Furthermore, obesity is linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and chronic arthropathy, which promotes intra-articular bleeding and the risk of fracture.Citation12,Citation14,Citation15,Citation20 In addition, musculoskeletal disorders caused by hemophilic arthropathy and aging are risk factors for falling injuries.Citation15 Thus, promotion of PA is especially important for PWH to reduce the risk of falling injuries and lifestyle-related diseases.

PA in PWH

Bleeding risk of PA in PWH

PA level has been positively correlated with bleeding risk among patients with severe and moderate hemophilia.Citation17,Citation21 In addition, significant differences were found in the prevalence of bleeding events, as those who exercised strenuously were more likely to incur bleeds due to trauma,Citation22 and 55% of PWH actively engaged in sports reported bleeding episodes associated with PA.Citation23 On the other hand, there was no significant correlation between PA level and bleeding frequency of target joints or joint function,Citation9,Citation22,Citation24 suggesting that the risk of bleeding is dependent on bleeding history, hemostatic control, and sport participation.Citation14 Therefore, administration of coagulation factor as a prophylactic or replacement therapy is essential for PWH before PA to prevent an increased risk from the level of PA.

Features of PA in PWH

The WHO recommends moderate PA of at least 60 minutes per day for children and adolescents aged 5–17 years, and moderate aerobic PA for at least 150 minutes per week or intensive aerobic PA for at least 75 minutes per week for adults aged 18–64 years.Citation19 These recommendations can also be applied to people with disabilities. However, health care providers should consider the level of disability, exercise ability, specific complication risk, and limitations associated with disease; accordingly adjust the type, load, and total duration of PA; and supervise patients individually.Citation19

As shown in ,Citation10,Citation11,Citation17,Citation21–Citation31 many previous studies have reported that PWH have the same or a lower degree of PA in comparison to healthy controls.Citation10,Citation11,Citation20,Citation22,Citation23,Citation25,Citation28,Citation32 One study states that more than half of patients with severe and moderate hemophilia do not perform recommended levels of PA.Citation21 It is also reported that PWH spent more time in sedentary behaviorCitation21,Citation23,Citation30,Citation31; even subjects with no arthropathy had muscle weakness,Citation2 and 60% managed hemophilia by avoiding PA.Citation33 In addition, in developing countries where prophylaxis is not performed, the sports participation remains poor.Citation25,Citation34 On the other hand, some studies found a higher level of PA in PWH than in healthy individuals.Citation17,Citation24,Citation28 PA can be measured in two ways – self-reporting and activity monitoring.Citation35 The former is widely used because it is simple and low cost, whereas the latter has possibilities for goal setting and quantified monitoringCitation30,Citation35 ().

Table 1 Summary of previous research about PA in PWH

Among the 14 studies listed in , ten were surveys of responses to questionnaires with three using the Modifiable Activity Questionnaire. Four of the surveys used activity monitoring with two using the Active Style Pro HJA-350IT. Those studies showed that PA in PWH was inversely correlated with age and positively correlated with muscle strength.Citation8,Citation10,Citation22,Citation23 In addition, PWH with the following characteristics were considered to have a low activity: those who started prophylaxis at the age of ≥3 years,Citation29 had impairment,Citation9 had a poor bone mineral density of lumbar spine,Citation25 and were obese or overweight.Citation36

Risk management for safe PA

There is a possibility that PA may increase the risk of bleeding. Therefore, risk management for trauma and bleeding is necessary for PWH to participate in PA. PWH should receive appropriate prophylactic administration of coagulation factors to reduce the risk of bleeding while participating in sports,Citation23 achieve good physical condition to undertake PA, have knowledge about first aid and PA, and choose the appropriate type of sports.Citation37 Therefore, besides the administration of coagulation factors, other factors are necessary for ensuring safety of PWH during PA.

Prophylactic treatment should be tailored to the bleeding pattern and lifestyle of individual patientsCitation6 and to ensure adequate levels of clotting factors before participating in PA.Citation23,Citation37,Citation38 Vigilant physical and orthopedic examinations in addition to making adjustments for various physical factors (eg, muscle strength, flexibility, durability, balance, coordination, and body fat content) are particularly important to avoid injury to target joints.Citation6,Citation14,Citation32,Citation37,Citation39 Selection of appropriate sports must be reached based on the individual’s physical ability and past history by consultation with a hemophilia care physician, orthopedic surgeon, rehabilitation doctor, physiotherapist, patients, and parents.Citation2,Citation8 In particular, physiotherapists play an important role in the selection of appropriate PA.

After a bleeding event, PWH should resume activities gradually to minimize the chance of a re-bleed.Citation14,Citation40 Therefore, physiotherapists should encourage the recovery of physical function after bleeding by individualized assessment and appropriate rehabilitation.Citation14 In addition, it is necessary to recognize the risk of bleeding and participation in certain sports. Low-risk sports include noncontact sports, such as swimming, walking, and bicycling, while high-risk sports include those involving contact or collision, such as martial arts.Citation1

When participating in sports, PWH should learn the rules and be familiar with current technologies, perform warm-up exercises, wear appropriate equipment, and notify coaches and fellow participants of their conditions.Citation14,Citation32,Citation39 Evidently, no sport is 100% safe.Citation2,Citation23 Immediately after a bleeding event, adequate replacement therapy and RICE (rest, ice, compression, elevation) are necessary.Citation14,Citation32 For PWH receiving inhibitor therapy, it is necessary to determine appropriate exercises for individuals and to monitor response to exercise based on careful assessment by the physiotherapist.Citation39,Citation41 In particular, it is necessary to carefully choose an exercise program for patients with high-titer inhibitors (>5 BU/mL) as the hemostatic response to bypass agents is less reliable.Citation9

Benefits to PWH from PA

PA confers several musculoskeletal benefits to PWH, such as improved muscle strength and joint stability,Citation8,Citation38,Citation39,Citation42 reduced joint pain,Citation8,Citation38 increased bone density and protection of joints,Citation8,Citation19,Citation32,Citation40 prevention from falling,Citation40 lower bleeding risk,Citation8,Citation39 and improved joint flexibility.Citation10–Citation12,Citation42 Other physical benefits include prevention of obesity,Citation16 heart disease,Citation13 hypertension,Citation13,Citation32 and diabetesCitation13,Citation32 and promotion of neuromuscular development.Citation1 PA also confers several benefits to mental health, such as improvement in depression,Citation32 self-steem,Citation1,Citation6,Citation8 social interactions,Citation2,Citation6,Citation8 self-efficacy,Citation26 happiness,Citation13 emotional status,Citation2,Citation8 social acceptance perception,Citation8 positive self-assessment,Citation8 and reduction of anxiety.Citation6,Citation8,Citation13,Citation26,Citation38 Continuous PA, rather than the type of exercise, is an important determinant of health-related quality of life, even for PWH.Citation8,Citation9,Citation40,Citation43 In particular, children achieve the greatest improvements in health-related quality of life by sports participation.Citation9

It has also been reported that PA increased endogenous factor VIII activity (10 minutes after the maximal exercise test) in patients with mild-to-moderate hemophilia.Citation44 Therefore, PA can confer many benefits to PWH in developing countries with limited access to pharmacologic treatments.Citation26,Citation34

Difficulty of exercise adherence

A German study reported that 79% of adolescents and 81.5% of adults with hemophilia considered daily exercise to be important.Citation45 However, many patients report limited PA, primarily because of fear of increased bleeding frequency, overprotection by parents, and the belief that joint disease cannot be prevented (reported by 36% of adolescent respondents).Citation14,Citation33,Citation34,Citation38,Citation46 On the other hand, only 31% of the respondents reported seeking treatment within 1 hour of a bleeding episode.Citation33 We believe that education of patients and their families is important for hemostatic therapy and essential for first aid.

Mental aspects of PWH are reported as follows: overprotection by familyCitation38; anxietyCitation38; and decrease in self-esteem, self-efficacy, self-acceptance,Citation26,Citation30,Citation38 exercise adherence,Citation47 and treatment compliance.Citation6 In addition, some boys with hemophilia in one study regretted the fact that their doctors or parents did not allow them to participate in sports of their choosing.Citation46 Therefore, many patients must be motivated to engage in PA,Citation48 suggesting the need for a behavior change approach.

Behavior change theory and techniques

For this section, it was assumed that PA was carried out under the suitable management of hemostasis. Therefore, education regarding hemostasis is very important.

Building trusting relationships

Thom and CampbellCitation49 identified factors influencing the relationship of trust between the patient and clinician, and thoroughly evaluating problems, understanding patient’s individual experience, expressing care, providing appropriate and effective treatment, communicating clearly and completely, building partnership/sharing power, and demonstrating honesty/respect for patient. Therefore, a knowledgeable clinician who focuses only on medical conditions of patients, would not be able to build their sufficient trust.

Motivation theory

Motivation theory involves promotion of PA by increasing self-determination; in the self-determination theory, motivation is classified as 1) amotivation (the absence of motivation itself), 2) extrinsic motivation (means of PA are other objectives), or 3) intrinsic motivation (PA itself has become a goal)Citation50 ().

Table 2 Classification of exercise motivation based on self-determination theory

Intrinsic motivation is considered the highest motivation of self-determination, while extrinsic motivation is classified as 1) external regulation (motivation by external factors, such as rewards and recommendations from others), 2) introjected regulation (motivation from obligation to PA), 3) identified regulation (motivation from the emotional need for PA), and 4) integrated regulation (motivation consistent with its own values).Citation51 In addition, it is assumed that the degree of self-determination is high in the aforementioned order, and it has been confirmed that PA is strongly related to increasing the degree of self-determination by observational studies and interventional studies.Citation51

Intrinsic motivation for promoting PA and exercise 1) emphasizes the individual, 2) promotes perceptions of choice, 3) promotes the intrinsic fun and excitement of exercise, and 4) promotes a sense of purpose by teaching the benefits of PA to health, optimal function, and quality of life, but it does not 1) overemphasize peer comparisons of performance, 2) undermine intrinsic focus by misusing extrinsic rewards, 3) turn exercise into a chore or render it boring, or 4) create amotivation through dissemination of inaccurate fitness information.Citation52

There are many reasons for patients to discontinue PA. Therefore, exercise prescription should encourage self-motivation to perform PA.

Self-efficacy

Improvement of self-efficacy is important to foster behavior changes.Citation53 In PA, self-efficacy is important to build confidence and encourage the individual to perform specific PA in particular environments.Citation53 Self-efficacy is the most interesting concept as specified factors and intervention targets for PA and is one of the most influential psychological factors in promotion of PA.Citation54 In addition, rehabilitation is promoted by improvement of self-efficacy.Citation30,Citation55

Methods to improve self-efficacy are presented in .Citation56 The following factors were found to be important to improve self-efficacy: 1) enactive attainment, 2) vicarious experience, 3) verbal persuasion, and 4) physiological state or emotional arousal.Citation56 Behavior modification can also improve self-efficacyCitation57 ().

Table 3 Source of self-efficacy information

Transtheoretical model

In the early 1980s, transtheoretical model (TTM) was first proposed as an intervention method based on the degree of patient motivation and has since been widely clinically applied to study various health behaviors.Citation57–Citation60 There are five stages in behavior (lifestyle) changes: 1) pre-contemplation, 2) contemplation, 3) preparation, 4) action, and 5) maintenance.Citation58–Citation60

Behavior change approach

The purpose of the promotion theory of PA is to promote independent participation in exercise, as supervised exercise should be limited to the early stages of an exercise regimen.Citation57 It is possible to increase PA levels of sedentary individuals and short-term (3–12 weeks) increases in PA are relatively easy to achieve.Citation57 However, long-term change (6–24 months) is much more difficult to achieve.Citation57 Methods to change behaviors and promote adherence to PA include: 1) TTM, 2) relapse prevention, 3) motivational counseling, and 4) self-monitoring.

In TTM, intervention matched to ability is necessary in order to proceed to the next stage of behavior change.Citation59,Citation61 Intervention in the pre-contemplation stage should focus on communication with the patient to elucidate the patient’s individual interests. There is no effect on persuasion because during this phase, patients do not recognize the associations between PA and their own health problems. Intervention for contemplation should explore the benefits of PA and disadvantages of physical inactivity. For some, this method is not effective, thus the conviction–confidence model should be employed.Citation62 In this model, the clinician assesses the patient’s readiness for behavior change within two dimensions: confidence and conviction. An intervention to increase the patient’s confidence, conviction, or both, can then be applied with the goal of helping the patient ().

Table 4 Information necessary for adaptation to the behavior change stage based on the transtheoretical model

Problems with PA faced by patients can be classified into four groups according to the confidence and conviction model. The easiest way to assess a patient’s conviction and confidence levels is to ask the patient to rate it on a visual analog scale of 1–10. Patients who think that PA is not important and have no confidence in PA should be provided information in the pre-contemplation stage. It can be difficult to achieve behavior change in patients who have confidence in PA, but do not think that it is important. Hence, these patients should receive counseling from the clinician. Building a trusting relationship is important to present the benefits of PA to the patient. Hence, the clinician should explore discrepancies between physical inactivity and important events in the patient’s life (eg, family and health) and should indicate the magnitude of the benefits of PA.

Strong resistance from a patient should be addressed in the long term while maintaining a trusting relationship during the pre-contemplation stage. Providing individualized information to match important events in the patient’s life (eg, a friend’s illness or birth of a grandchild) to stress the importance of PA is necessary for such patients.

Patients who think PA is important, but do not have confidence in performing PA should be encouraged to enhance self-efficacy, while paying attention to past successful experiences after the importance of PA is emphasized. Such patients should receive added support to realize short-term goals. In addition, intervention and preparation should be encouraged to support the decision to begin PA.

The determination of the patients themselves through discussions of both short- and long-term goals is important. Intervention should also consider the possibility of relapse, a phenomenon in which the patient reverts to the stage before the behavior change, despite entering the action and maintenance stage. In these cases, confirmation and praise of the beneficial results brought about by behavior change are important to encourage continued participation in PA.

Interventions for maintenance should be implemented to prevent relapse. It is necessary to consider the influence of personal problems on the patient’s willingness to participate in PA (eg, when the patient does not want to exercise) through discussion. Implementation of viable measures to prevent relapse proposed by the patient is both important and effective. Regarding relapse measures, reversion to the pre-contemplation or contemplation stage indicates that the patient does not fully recognize the importance of exercise. Therefore, before progressing to the next stage, intervention may be necessary to provide further information about the benefits of PA. Reversion to the preparation stage is caused by a lack of self-confidence, which is intended to overcome situations, in which the patient does not want to perform exercise (eg, during vacation or bad weather). In such cases, clarification of these barriers and discussion of future plans are necessary.

Self-monitoring enables self-strengthening and objective self-evaluation by observing and/or recording self-behaviorCitation63 and is an effective method to achieve behavior change for patients with PWH,Citation30 hypertension,Citation64 obesity,Citation63 smoking,Citation65 diabetes,Citation66 and ischemic heart disease.Citation67 Process and outcome assessments are important to promote exercise adherence.Citation35 Feedback on exercise results will contribute to exercise adherence.Citation35 Process assessment focuses on frequency of exercise, improving knowledge, response rate, and submission rate of challenges (reporting rates). In outcome assessment, psychological indicators in addition to physical indicators (number of steps, PA, physical fitness, and body weight, etc) are useful to promote exercise adherence.

Motivational counseling, as proposed by Miller and Roll-nick, is a technique commonly employed to achieve behavior change by inducing patient motivation, rather than clinician direction.Citation68 Honoring patient autonomy can also increase self-confidence for behavior change and also encourage motivation. The method has four guiding principles: 1) to resist the righting reflex, 2) to understand and explore patient motivation, 3) to listen with empathy, and 4) to empower the patient by offering hope and optimism.Citation68

Considerations when introducing a behavior change approach

Behavior change stage and self-monitoring intervention in PWH

As mentioned earlier, many PWH will find it difficult to maintain participation in PA for various reasons, such as fear of bleeding. To address this issue, stages in TTM (ie, pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, and maintenance) were evaluated in 15 (46.9%), five (15.6%), six (18.8%), and three (9.4%) PWH, respectively.Citation30 After diagnostic images and physical function were assessed, individual home exercise was instructed. In addition, we conducted randomized controlled trials of self-monitoring.Citation30 Subjects included 32 male outpatients aged 26–64 years who were randomly allocated to self-monitoring (n=16) and control (n=16) groups. Patients in both groups received home exercise guidance and an activity monitor, and those in the self-monitoring group were given a self-monitoring approach. Patients in the self-monitoring group were equipped with a feedback system via the Internet and mobile phone. The self-monitored items included bleeding history, injection of coagulation factor, PA, and frequency of home exercise. In addition, the patients in the control group were not required to report their home exercise status during the intervention period. Most patients (90.3%) self-reported bleeding episodes and frequency of home exercises/PA. Among all patients examined, no change in pain or bleeding frequency was noted by intervention for 8 weeks. However, exercise adherence, self-efficacy, and strength of knee extension significantly improved in the self-monitoring group compared with the control group.

Self-monitoring in our study was designed so that the subjects had access to a server and received feedback results of exercise (eg, the number of times the patient performed the exercise and PA, blooding frequency, and injection of the coagulation factor) with the passage of time shown in graphs and tables after the input of the monitored items. Self-strengthening and objective self-evaluation were facilitated by self-monitoring.Citation54 Specifically, the patients were instructed to report bleeding events and the quantified PA using an activity monitor to encourage consideration of possible associations. Positive feedback was achieved once the patient realized that bleeding was not necessarily associated with PA. It is considered that self-monitoring enabled the patients to appreciate the benefits of controlling self-behavior through the recognition of motion results, creating self-efficacy, and improving exercise adherence. It is reported that self-efficacy is strengthened by self-monitoring. For these reasons, self-efficacy is considered to contribute to exercise adherence. In this study, 84.4% of patients had severe hemophilia, more than half had severe arthropathy of the knee joints, and the average patient age was 42.8 years. Therefore, these results illustrate the beneficial effects of self-monitoring by patients exhibiting some factors that inhibit PA, in accordance with the results of previous studies. Hence, a randomized controlled trial focusing on the influence of self-monitoring identified in this study is warranted. If intervention was conducted for a greater number of subjects, it will be possible to further examine the influence of SM according to the motivation and stage of TTM.

Case report

We report the case of a 16-year-old boy with severe hemophilia A, severe arthropathy in both knee joints (Arnold–Hilgartner stage V),Citation69 and a history of inhibitor who achieved remarkable improvements in the activities of daily living and PA using PT and self-monitoring intervention. Written informed consent for publication of this case report was obtained from the patient and his family. Therefore, ethical approval was not sought from the committee of research ethics from the Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo. High inhibitor titers were noted shortly after birth. Immune tolerance induction was initiated when he was 2 years old. However, repeated intra-articular bleeding in both knee joints was accompanied with synovitis. Therefore, he lost the ability to walk at the age of 6 years. PT was commenced at the age of 8 years.

He presented with flexion contractures in both knee joints (−90/−65°) and both hip joints (−30/−30°) and whole-body muscle weakness caused by arthropathy, disability, and physical inactivity. Manual muscle testing of the trunk, hip extensor, hip abductor, knee extensor, knee flexor, ankle extensor, and ankle flexor was evaluated as fair, fair/fair+, fair/fair+, poor−/poor, good/good, good/good, and poor+/poor+, respectively. Stage of TTM was preparation and motivation was amotivation. In addition, because standing and walking were difficult, he was unable to perform most of the home exercises.

Mild load and play exercises were commenced because of a bleeding risk due to inhibitors. Aggressive PA could not be performed. However, when PT became constant, his motivation was improved to external regulation. With increasing age, motivation was changed to identified regulation. Furthermore, intrinsic motivation was also added with the improvement of physical function and inhibitor eradication by the effect of continued immune tolerance induction when he was 12 years old. At that time, he was able to walk with the assistance of two crutches. However, prolonged physical inactivity remained an obstacle to achieving long distances. Therefore, we introduced a self-monitoring method using an activity monitor in addition to home exercise. At that time, the patient was prompted to periodically set specific goals, such as a distance of continuous gait after 1 year.

After introduction of self-monitoring, the attending physician and physiotherapist periodically confirmed the self-monitoring results. In addition, the patient received feedback from physical function assessment results. He and his family received praise, advice, and suggestions based on these results. We regularly reviewed the status of goal achievement and made changes to the home exercise routine and goals as necessary.

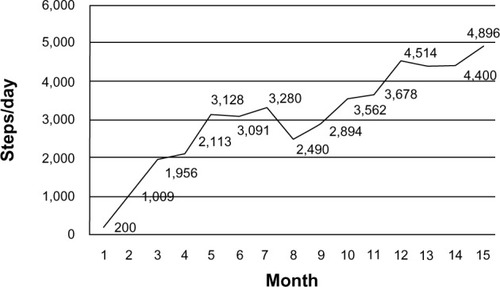

After 15 months of self-monitoring, the number of steps increased from ~200 per day to ~5,000 per day, and self-efficacy also improved. In addition, flexion contractures in both knee joints (−30/−10°) and both hip joints (−10/10°) had improved. The results of the manual muscle testing of the trunk, hip extensor, hip abductor, knee extensor, knee flexor, ankle extensor, and ankle flexor improved to good, good/good, good/good, poor−/poor+, normal/normal, normal/normal, and good/good, respectively. Activities range was expanded to the use of public transportation, and the TTM stage improved to action ().

Figure 1 Step count after 15 months of self-monitoring intervention for PWH.

In this case, self-monitoring was effective by introduction at a time when motivation changed to intrinsic motivation. In future studies, barriers to PA due to the time required for academic and university preparation as a possible cause of relapse should be considered. Thus, even patients with severe hemophilia having a history of inhibitors, severe arthropathy, and physical dysfunction can improve PA.

In conclusion, selection of PT programs based on coagulation laboratory data and physical function assessment, intervention based on TTM and motivational theory, and introduction of self-monitoring upon improved self-efficacy were found to be useful interventions.

Considerations in behavior change approach

The purpose of this review was to discuss changes in exercise behavior, rather than to present exercise programs suitable for PWH; thus, no specific exercise guidelines were included. As a limitation of this theory, comparatively few studies have evaluated the use of this model across behaviors among PWH. Further research in this area is much needed. In addition, one of the criticisms of TTM has been its limited usefulness among diverse ethnic groups and low socioeconomic backgrounds.Citation68 In particular, behavior change approaches for PWH with arthropathy and inhibitors can complement the effects of PT and exercise guidance. Therefore, it is important to prescribe individualized exercise regimens based on the assessment of hemorrhagic tendency, bleeding history, prophylactic treatment, arthropathy, and physical function.

Conclusion

Many PWH find it difficult to continue PA because of aging, fear of bleeding, insufficient recognition of the benefits of PA, and psychological problems. Therefore, it is necessary to administer prophylactic and replacement therapies before the patient participates in an exercise program. In addition, the benefits and risks of participating in sports should be carefully explained. For patients who find it difficult to participate in PA, it is necessary to plan individual behavior change approaches and encourage improvement in self-efficacy.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Treatment Guidelines Working Groupon Behalf of the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) [webpage on the Internet]Guidelines for the Management of Haemophilia2nd edBlackwell Publishing Ltd2012 [Available July 6, 2012; about 7–8, 11, 59–61]. Available from: http://www1.wfh.org/publication/files/pdf-1472.pdfAccessed August 14, 2015

- GomisMQuerolFGallachJEGonzálezLMAznarJAExercise and sport in the treatment of haemophilic patients: a systematic reviewHaemophilia2009151435418721151

- OldenburgJZimmermannRKatsarouOCross-sectional MRI study investigators. Controlled, cross-sectional MRI evaluation of joint status in severe haemophilia A patients treated with prophylaxis vs. on demandHaemophilia201521217117925470205

- DiMicheleDMLeeCABerntorpEEHootsWKTextbook of HemophiliaMalden, MABlackwell Publishing2005

- MorfiniMHayaSTagarielloGEuropean study on orthopaedic status of haemophilia patients with inhibitorsHaemophilia200713560661217880451

- PetriniPSeuserAHaemophilia care in adolescents-compliance and lifestyle issuesHaemophilia2009151151919125936

- FujiiTAmanoKAtsumiT2013 revised edition: hemostatic treatment guidelines for hemophilia patients without inhibitorsJap J Thromb Hemostasis2013246619639

- Von MackensenSQuality of life and sports activities in patients with haemophiliaHaemophilia2007132384317685923

- KhairKLittleyAWillAvon MackensenSThe impact of sport on children with haemophiliaHaemophilia201218689890522630612

- FalkBPortalSTiktinskyRWeinsteinYConstantiniNMartinowitzUAnaerobic power and muscle strength in young hemophilia patientsMed Sci Sports Exerc2000321525710647529

- EngelbertRHHPlantingaMVan der NetJAerobic capacity in children with hemophiliaJ Pediatr2008152683383818492527

- HofstedeFGFijnvandraatKPlugIKamphuisenPWRosendaalFRPetersMObesity: a new disaster for haemophilic patients? A nationwide surveyHaemophilia20081451035103818637967

- MulderKCassisFSeuserDRANarayanPDalzellRPoulsenWRisks and benefits of sports and fitness activities for people with haemophiliaHaemophilia200410suppl 416116315479391

- PhilpottJHoughtonKLukeAPhysical activity recommendations for children with specific chronic health conditions: juvenile idiopathic arthritis, hemophilia, asthma and cystic fibrosisPaediatr Child Health201015421322521455465

- SammelsMVandesandeJVlaeyenEPeerlinckKMilisenKFalling and fall risk factors in adults with haemophilia: an exploratory studyHaemophilia201420683684525354771

- WongTEMajumdarSAdamsEHealthy Weight Working GroupOverweight and obesity in hemophilia: a systematic review of the literatureAm J Prev Med2011416 suppl 4S369S37522099360

- GonzálezLMPeiró-VelertCDevís-DevísJComparison of physical activity and sedentary behaviours between young haemophilia A patients and healthy adolescentsHaemophilia201117467668221299746

- DishmanRKExercise Adherence: It’s Impact on Public HealthChampaign, ILHuman Kinetics1988

- World Health Organization [webpage on the Internet]Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health2010 [about 7–11,, 18–33]. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599979_eng.pdfAccessed August 14, 2015

- FearnMHillKWilliamsSItalian Association of Haemophilia Centres (AICE)Health status and quality of life of elderly persons with severe hemophilia born before the advent of modern replacement therapyJ Thromb Haemost20097578078619220727

- BroderickCRHerbertRDLatimerJDoornNPatterns of physical activity in children with haemophiliaHaemophilia2013191596422762509

- TiktinskyRKenetGDvirZPhysical activity participation and bleeding characteristics in young patients with severe haemophiliaHaemophilia200915369570019298376

- SherlockEO’DonnellJSWhiteBBlakeCPhysical activity levels and participation in sport in Irish people with haemophiliaHaemophilia2010161e202e20919878332

- CzepaDVon MackensenSHilbergTHaemophilia and Exercise Project (HEP): subjective and objective physical performance in adult haemophilia patients – results of a cross-sectional studyHaemophilia2012181808521752158

- Tlacuilo-ParraAInactivity is a risk factor for low bone mineral density among haemophilic childrenBr J Haematol2008140556256718275434

- BuxbaumNPPonceMSaidiPMichaelsLAPsychosocial correlates of physical activity in adolescents with haemophiliaHaemophilia2010116 suppl 465666120331760

- FearnMHillKWilliamsSBalance dysfunction in adults with haemophiliaHaemophilia201016460661420331756

- GroenWGTakkenTVan Der NetJHeldersPJMFischerKHabitual physical activity in Dutch children and adolescents with haemophiliaHaemophilia2011175e906e91221539696

- KhawajiMAstermarkJAkessonKBerntorpEPhysical activity and joint function in adults with severe haemophilia on long-term prophylaxisBlood Coagul Fibrinolysis2011221505521119510

- GotoMTakedaniHHagaNSelf-monitoring has potential for home exercise programmes in patients with haemophiliaHaemophilia2014202e121e12724418413

- GotoMTakedaniHKubotaMHagaNNittaOThe effect of a home exercise program for patients with hemophiliaJ Jap Prim Care Assoc20143712226 Japanese

- HeijnenBMauserEPRoosendaalGParticipation in sports by Dutch persons with haemophiliaHaemophilia20006553754611012699

- NazarroAMOwensSHootsKLarsonKLKnowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of youths in the US hemophilia population: results of a national surveyAm J Public Health20069691618162216873741

- BuzzardBMPhysiotherapy, rehabilitation and sports in countries with limited replacement coagulation factor supplyHaemophilia2007132444617685924

- SallisJFOwenNGPhysical Activity and Behavioral MedicineThousand Oaks, CASAGE Publications1998

- Douma-van RietDCEngelbertRHvan GenderenFRTer Horst-De RondeMTde Goede-BolderAHartmanAPhysical fitness in children with haemophilia and the effect of overweightHaemophilia200915251952719347992

- SeuserABoehmPKurmeASchumpeGKurnikKOrthopaedic issues in sport for persons with haemophiliaHaemophilia2007132475217685925

- BoadasAOsorioMGibraltarADesafio del Caribe ProjectFavourable impact of regular swimming in young people with haemophilia: experience derived from ‘Desafio del Caribe’ projectHaemophilia2015211e12e1825359594

- HeijnenLThe role of rehabilitation and sports in haemophilia patients with inhibitorsHaemophilia2008146455119134033

- ForsythALQuonDVKonkleBARole of exercise and physical activity on haemophilic arthropathy, fall prevention and osteoporosisHaemophilia2011175e870e87621435116

- Rodriguez-MerchanECHednerUHeijnenLPrevention of haemophilic arthropathy during childhood. May common orthopaedic management be extrapolated from patients without inhibitors to patients with inhibitors?Haemophilia2008146688119134036

- KargarfardMDehghadaniMGhiasRThe effect of aquatic exercise therapy on muscle strength and joint’s range of motion in hemophilia patientsInt J Prev Med201341505623412736

- RejeskiWJBrawleyLRShumakerSAPhysical activity and health-related quality of lifeExerc Sport Sci Rev199624711088744247

- GroenWGden UijlIEvan der NetJGrobbeeDEde GrootPGFischerKProtected by nature? Effects of strenuous physical exercise on FVIII activity in moderate and mild haemophilia A patients: a pilot studyHaemophilia201319451952323510308

- FrommeADreeskampKPollmannHThorwestenLMoorenFCVolkerKParticipation in sports and physical activity of haemophilia patientsHaemophilia200713332332717498083

- SchoenmakersMAGulmansVAHeldersPJvan den BergHMMotor performance and disability in Dutch children with haemophilia: a comparison with their healthy peersHaemophilia20017329329811380634

- GreeneWBStricklerEMA modified isokinetic strengthening program for patients with severe hemophiliaDev Med Child Neurol19832521891966852383

- De la Corte-RodriguezHRodriguez-MerchanECThe role of physical medicine and rehabilitation in haemophiliac patientsBlood Coagul Fibrinolysis20132411923103725

- ThomDHCampbellBPatient-physician trust: an exploratory studyJ Fam Pract19974421691769040520

- RyanRMDeciELSelf-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-beingAm Psychol2000551687811392867

- TeixeiraPJCarraçaEVMarklandDSilvaMNRyanRMExercise, physical activity, and self-determination theory: a systematic reviewInt J Behav Nutr Phys Act201297822726453

- WhiteheadJRserial on the InternetPhysical Activity and Intrinsic MotivationThe PCPFS Research Digest19931218 Available from: https://www.presidentschallenge.org/informed/digest/docs/199305digest.pdfAccessed August 14, 2015

- BanduraASelf-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral changePsychol Rev1977842191215847061

- DishmanRKSallisJFDeterminants and interventions for physical activity and exercisePublic Health Rep198510021581713920714

- KaivantoKKEstlanderAMMonetaGBVanharantaHIsokinetic performance in low back pain patients: the predictive power of the Self-Efficacy ScaleJ Occup Rehabil199552879924234579

- BanduraASocial Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive TheoryNew Jersey, NJEngle wood Cliffs1986

- BiddleSJMutrieNPsychology of Physical Activity: Determinants, Well-Being and InterventionsLondonRoutledge1995

- ProchaskaJODiClementeCCTranstheoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of changePsychotherapy1982193279288

- OkaKRecent trends of research on exercise adherence utilizing the transtheoretical model of behavior changeRes Phys Educ2000454543561 Japanese

- BurbankPMRiebeDPromoting Exercise and Behavior Change in Older Adults: Interventions with the Transtheoretical ModelNew York, NYSpringer Publishing Company2001

- BurbankPMReibeDPadulaCANiggCExercise and older adults: changing behavior with the transtheoretical modelOrthop Nurs2002214516112224187

- KellerVFWhiteMKChoices and changes: a new model for influencing patient health behaviorJ Clin Outcomes Manage1997463336

- WingRRHillJOSuccessful weight loss maintenanceAnnu Rev Nutr20012132334111375440

- CarnahanJENugentCAThe effects of self-monitoring by patients on the control of hypertensionAm J Med Sci1975269169731130437

- IsraelACRaskinPAPravderMDThe effects of self-monitoring of smoking and awareness of accuracy feedback upon a concurrent behaviorAddict Behav197942199203474270

- WorthRHomePDJohnstonDGIntensive attention improves glycaemic control in insulin-dependent diabetes without further advantage from home blood glucose monitoring: results of a controlled trialBr Med J19822856350123312406812820

- IzawaKWatanabeSOmiyaKEffect of the self-monitoring approach on exercise maintenance during cardiac rehabilitation: a randomized, controlled trialAm J Phys Med Rehabil200584531332115829777

- MillerWRRollnickSMotivational Interviewing. Preparing People for Change2nd edNew York, NYGuilford Press2002

- ArnoldWDHilgartnerMWHemophilic arthropathy. Current concepts of pathogenesis and managementJ Bone Joint Surg1977593287305849938

- GilbertMSProphylaxis: musculoskeletal evaluationSemin Hematol1993303 supple2368367740