Abstract

Combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma (CC) is a rare and aggressive primary hepatic malignancy with significant histological and biological heterogeneity. It presents with more aggressive behavior and worse survival outcomes than either hepatocellular carcinoma or CC and remains a diagnostic challenge. An accurate diagnosis is crucial for its optimal management. Major hepatectomy with hilar node resection remains the mainstay of treatment in operable cases. Advances in the genetic and molecular characterization of this tumor will contribute to the better understanding of its pathogenesis and shape its future management.

Introduction

Combined or mixed hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma (cHCC-CC) is a distinct type of primary liver cancer sharing unequivocal phenotypical characteristics of both hepa-tocellular carcinoma (HCC) and cholangiocarcinoma (CC).Citation1,Citation2 It is a rare entity with a variably reported incidence between 0.4% and 14.2% across a number of studies.Citation1,Citation3–Citation6 This is considered to be an underestimation not only due to the diagnostic challenges associated with this malignancy but also due to a previous lack of consensus on the nomenclature.Citation7

The histogenesis and natural history of this rare malignancy remain elusive;Citation8 however, the widely accepted origin of cHCC-CC is a common hepatic stem cell.Citation9,Citation10 There is conflicting evidence in the existing literature with regard to the epidemiological and clinical features of cHCC-CC. Several studies have suggested similarities to HCC,Citation11–Citation13 whereas others related it to CC.Citation1,Citation6 There is also growing evidence suggesting that cHCC-CC has intermediate clinical features between HCC and CC,Citation14 which is also reflected in patient survival outcomes. cHCC-CC displays a rather aggressive behavior and is associated with poorer prognosis compared to HCC and more favorable than CC in patients undergoing liver resection.Citation12,Citation15–Citation18 An accurate perioperative diagnosis is of paramount importance and directs the consequent surgical management of this tumor, with major hepatectomy being the best therapeutic approach.Citation17,Citation18 The management of this tumor is hindered by the lack of international guidelines, while the role and indications of liver transplantation (LT) remain equivocal.Citation18,Citation19

Here we present a review on this challenging primary hepatic tumor with a particular focus on its genetics, molecular biology, and therapeutic interventions.

Classification

The initial description of cHCC-CC dates back to 1903, but was more comprehensively studied later in 1949 when Allen and Lisa classified it in three different histological types (type A, B, and C) depending on the presence of HCC and CC: at different sites in the same liver, at adjacent sites, or in the same tumor, respectively.Citation4 Subsequently, Goodman et al reclassified these tumors into type I (collision) characterized by the coincidental existence of both HCC and CC in the same liver, type II (transitional) characterized by the presence of areas of transition between HCC and CC, and type III (fibrolamellar), which resemble the fibrolamellar variant of HCC with the additional presence of pseudo-glands producing mucin.Citation1 WHO recognized cHCC-CC as a distinct entity and further classified it into two main types: the classical type, which is characterized by intermixed areas of typical HCC and CC and the presence of transition zones with intermediate morphology of both types, and the type with stem cell features, which is less common and further subdivided into typical, intermediate, and cholangiocellular (CLC) subtype ().Citation2

Table 1 The 2010 WHO classification of cHCC-CC. Adapted with permission from Bosman, FT, Carneiro,F, Hruban, RH, Theise, ND. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. IARC, Lyon, 2010.Citation2

Certain histopathological criteria have been established for the definitive diagnosis of cHCC-CC, which require the presence of fully differentiated components of hepatocellular and CC intimately mixed with concurrent evidence of transition zones comprising cells with intermediate morphology.Citation2 This distinguishes it from HCC and CCs found in the same liver lobe, which represent collision tumors.

Epidemiology and clinical profile

The demographic and clinical profile of combined HCC is not yet fully characterized. Due to the rarity of this malignancy, the majority of data are generated from single-center retrospective studies with relatively small cohort sizes and significant variations in the studied populations. Although risk factors for HCC and CC have been established, this is not the case for cHCC-CC, and this yet remains an elusive matter.Citation6,Citation20 The most common risk factors for HCC include liver cirrhosis, infection with hepatotropic viruses such as Hepatitis B Virus (HBV), Hepatitis C virus (HBC) and Hepatitis D virus (HDV), alcoholic liver disease, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.Citation21,Citation22 Risk factors associated with CC involve primary sclerotic cholangitis, liver fluke infestation, hepatolithiasis, and exposure to Thorotrast.Citation23 A number of studies conducted in Asian patients have demonstrated similarities between cHCC-CC and HCC, which involve strong male predominance, underlying liver cirrhosis, and serologically confirmed hepatitis.Citation3,Citation24–Citation28 On the contrary, several studies originating from Western countries supported a resemblance between cHCC-CC and CC with no gender predisposition and absence of hepatitis.Citation1,Citation6,Citation29,Citation30 To add to the existing ambiguity, other studies have suggested that cHCC-CC has a distinct clinical profile with intermediate characteristics to those of HCC and CC.Citation3,Citation14 This inconsistency is further compounded by the previous absence of accurate histological diagnostic criteria for cHCC-CC.

Histogenesis

The histogenesis of cHCC-CC remains elusive and has been a subject of debate. The most prominent hypothesis is that it derives from bipotent hepatic progenitor cells, which are intermediate stem cells capable of undergoing bidirectional differentiation into hepatocytes and bile duct epithelial cells.Citation31–Citation33 However, Moeini et al suggested that cHCC-CCs may be derived from more than one cell of origin. They performed gene expression profiling showing a biliary committed precursor for CLC type and a biphenotypic progenitor-like precursor for the classical and other stem cell subtypes.Citation34

The monoclonal origin of cHCC-CC was supported by Fujii et alCitation35 who used microdissection and DNA extraction showing that both hepatocellular and CLC components of these tumors share identical allelic loses.Citation35 On a similar note, another study demonstrated that a primary cell line derived from resected cHCC-CC could differentiate into either HCC or CC by changing the different growth conditions.Citation36

Diagnosis

Histopathology and IHC

A definitive diagnosis of cHCC-CC can only be made after histopathological assessment of a representative biopsy. In clinical practice, this may mean that a single pass biopsy results in an incorrect diagnosis due to sampling a nonrepresentative area. Therefore, when a diagnosis of cHCC-CC is suspected, extensive biopsies should be considered to increase diagnostic accuracy. Despite this, diagnosis may not be established until histopathological examination of the resected specimen.

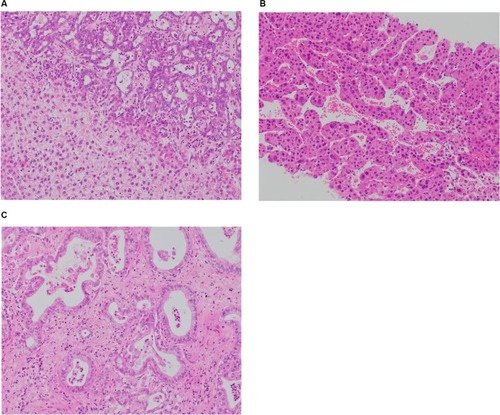

To meet the diagnostic criteria, the sample must show clear evidence of hepatocellular and biliary differentiation with the two types of tumor cells intermingling and transition zones where the cells demonstrate intermediate morphology ().Citation2 Patients may have a collision tumor with both HCC and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), but if there are separate foci of disease with no integration of tumor cells and no transition zones then this does not constitute a true cHCC-CC. Tumors may have a preponderance of either tumor type, which will in turn influence the features of the disease.

Figure 1 (A) Combined hepatocellular and cholangiocellular carcinoma. A single tumor nodule shows two different histological components, one with glandular differentiation and biliary immunoprofile consistent with cholangiocarcinoma (upper area of the picture) and one with a well-to-moderately differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (lower part of the picture); H&E staining. (B) Moderately differentiated HCC, trabecular pattern. Cellular variability with scattered large hyperchromatic nuclei; H&E staining, 100×. (C) Moderately differentiated intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Glandular structures are variable in size and shape, in a sclerosed stroma; H&E staining, 100×.

HCC differentiation is determined by the presence of bile-producing cells, Mallory-Denk bodies, bile canaliculi, and a pseudoglandular/trabecular growth pattern. CC differentiation is characterized by mucin-producing biliary epithelium forming true glandular structures and surrounding desmoplastic stroma.Citation37 cHCC-CC demonstrates independent biphenotypic differentiation; each component can be well to poorly differentiated.

cHCC-CCs also demonstrate an immunohistochemistry (IHC) profile consistent with both hepatic and biliary phenotypes. For the HCC component, this would include positive staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), HepPar1, CD-10, CAM5.2, and glypican-3. For the CC component, this includes positive staining for mucin, which is essential to demonstrate the biliary component, CK7, CK19, and AE1.Citation38 Transition zones typically stain for CC cytokeratins CK7, CK19, and the hepatocellular marker HepPar-1. The presence of albumin mRNA detected by in situ hybridization is an additional hepatocellular marker seen in the transition zone that may differentiate the tumor from ICC.Citation30 The cHCC-CC with stem cell features subtype will also characteristically stain positive for CK7, CK10, CD56, c-KIT, NCAM, DLK-1, and EpCAM.Citation39 However, IHC does not differentiate between HCC with inflammation of the biliary tree vs cHCC-CC. Examination of the biopsy should assess for the presence of desmoplastic stroma rather than the inflammatory cells of ductal reactivity, in order to confirm that the diagnosis is cHCC-CC.Citation31

Raised alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is associated with HCC and raised Ca19–9 associated with CC. In patients with a radiological diagnosis of either HCC or CC, a discordant pattern of tumor markers or a pattern of synchronously raised tumor markers should be a warning to consider the diagnosis of cHCC-CC.Citation2,Citation38 Patients with cHCC-CC tend to have a more modestly raised AFP than patients with HCC.

Imaging

A radiological diagnosis of cHCC-CC can be difficult to make as this tumor presents with heterogeneous imaging characteristics. The presence of overlapping radiological features of HCC and CC mandates a biopsy for definitive diagnosis. The predominant histologic component within the tumor will determine the predominant radiological features.

On ultrasound, the appearances of cHCC-CC are nonspecific. Lesions may be visualized as a round hypoechoic mass with a central hyperechoic focus or a heterogeneous hypoechoic mass.Citation40 While ultrasound is unlikely to be sufficient to diagnose cHCC-CC, it can be of use to guide biopsy toward appropriate lesions and thus play a role in the evaluation of such patients.

The computed tomography (CT) appearances vary according to the proportion and distribution of HCC and CC components and also according to the subtype of CC. Features suggestive of an HCC on CT imaging include arterial phase diffuse enhancement, portal venous washout, and enhanced pseudocapsule on delayed imaging. On the other hand, features suggestive of a CC on CT imaging are arterial peripheral ring enhancement, progressive fibrous stroma central enhancement, dilation of the biliary tree, and retraction of the capsule.Citation41 cHCC-CC may show any of these features to a mixed degree.

Multiple studies have examined MRI appearances of cHCC-CC with mixed results. Some report that the tumor more closely resembles HCC,Citation42 while others suggest that MRI appearances are more similar to ICC or metastases.Citation43,Citation44 This likely reflects the heterogeneous nature of the disease and different cohorts studied. Important MRI features that may indicate a diagnosis of cHCC-CC include the presence of washout, washout and progression in the same lesion, intralesional fat, and hemorrhage.Citation42 On T1w imaging, cHCC-CC appears hypointense, while on T2w imaging, lesions demonstrate an intermediate to high signal intensity with or without a central hypointense focus.Citation42

The MRI contrast agent gadoxetic acid has both perfusion-selective and hepatocyte-selective features to help distinguish between cHCC-CC and ICC or metastases. The features of cHCC-CC with contrast-enhanced MRI are still diverse due to the heterogeneous histological features; therefore, the use of contrast cannot always differentiate between HCC and cHCC-CC.Citation45

summarizes two proposed classification systems of cHCC-CC based on CT patterns of enhancement. Aoki’s type A and Sanada’s type 3 pattern are the most suggestive of cHCC-CC on imaging and tumors displaying that these characteristics should undergo further evaluation.Citation27,Citation46

Table 2 Proposed radiological classifications based on enhancement patterns

More widely adopted is the Liver Imaging-Reporting and Data System (Li-RADS) providing a standardized approach to reporting all liver lesions on the basis of MRI and CT imaging.Citation47 This system was developed in an attempt to standardize radiological criteria for diagnosing HCC. Lesions are labeled with increasing numbers representing increasing likelihood that a lesion is HCC – from LR-1 at 0% probability to LR-5 at 100% probability. Intrahepatic malignancy that is not HCC is labeled as LR-M. Subsequent analysis supports that this system differentiates between HCC and cHCC-CC. The majority of cHCC-CC cases reviewed against the Li-RADS criteria demonstrated ancillary features favoring non-HCC malignancy, sufficient for them to be recorded as LR-M.Citation47 In their study, Potretzke et al reviewed 61 cases of biphenotypic primary liver carcinomas using Li-RADS, version 2014, demonstrating that the addition of ancillary features to major features had superior diagnostic accuracy over the sole use of major features.Citation48

Studies suggest that radiological features can be used to provide prognostic information about cHCC-CC. Tumors, which are radiologically HCC predominant, have a better prognosis from ICC-predominant subtypes.Citation49

Genetic characterization of cHCC-CC demonstrates a diverse range of mutations, which overlap with mutations seen in HCC and CC. Understanding the genetic signature specific to cHCC-CC could help differentiate between these diagnoses. Genetic profiling could help define subtypes with cHCC-CC and identify therapeutic targets. It could also provide information on etiology, histogenesis, and prognosis. Genetic and epigenetic evaluation of tumors has been carried out in HCC and CC, but only small studies have currently been undertaken in cHCC-CC.

In cHCC-CC, the genetic landscape is similar across both HCC and CC components, proving that this is a distinct tumor type rather than a collision of two separate cancers. Whole-genome analysis of copy number variations comparing the HCC and CC components of the same tumor found a concordant trend between copy number gain or loss in both components.Citation50

In order to identify potential therapeutic targets, mutations within particular signaling pathways involved in carcinogenesis have been evaluated. This demonstrates cHCC-CC has features in common with both HCC and ICC. Pathways identified in patients with cHCC-CC that may provide therapeutic targets include MAPK, P53, pI3K–AKT–mTOR, and the Notch–Hedgehog pathway.Citation51

While some mutations are common to all primary liver cancers, other mutations are more specific and, if identified, may aid diagnosis. For example, mutations in tumor-suppressor gene TP53 are seen in all tumor types, although it is more prevalent in cHCC-CC (27%–100%) and HCC (26%) in comparison with CC (0%–11%).Citation50,Citation51 These are summarized in .

Table 3 Common genetic alterations seen in HCC, CC, and cHCC-CCCitation41,Citation50,Citation85

Gene profiling by microarray confirms that cHCC-CC displays a combination of the upregulated and downregulated genes seen in HCC and ICC. There are a significant number of differently expressed genes between ICC and HCC, and there is a less marked yet still significant difference between ICC and cHCC-CC supporting that these tumors are distinct entities.Citation52 The pattern of differentially expressed genes as assessed by microarray could allow for more accurate diagnosis in cases of diagnostic uncertainty.

A targeted gene panel revealed that mutations in genes KRAS, ARID1A, TERT promoter, and TP53 are associated with different clinical phenotypes of cHCC-CC ().Citation53 For example, patients with ARID1A gene mutations were more likely to report a history of alcohol excess. Similar correlations with mutations in ARID1A are seen in HCC and ICC. Studies suggest that ARID1A mutations occur in response to oxidative stress, which may be induced by alcoholic liver disease. Recently, mutations to IDH1/H2 have been identified in HCC tumors.Citation54 These tumors had a histopathological picture of HCC but clinical and genetic features of CC and HCC. This generated the hypothesis that IDH1/H2 mutations could shift primary liver tumors toward a biliary phenotype.

Table 4 Mutational landscape of cHCC-CC with clinical–pathological phenotype correlatesCitation53

Patients with mutations in the TERT (telomerase reverse transcriptase) promoter gene were more likely to have a history of underlying hepatitis B. TERT promoter mutations are also commonly seen as an early mutation in patients with HCC on a background of chronic hepatitis.Citation53 Specific mutations in TP53 are associated with a shorter prognosis in patients with HCC. The same mutations have been identified in patients with cHCC-CC. The data do not currently confirm whether these mutations are prognostic markers in cHCC-CC also.Citation51

Recognition of these mutations may give clues on the etiology of the tumor. However, confounding factors and causal links have not been established from current cHCC-CC studies. Although our knowledge of the genetics of cHCC-CC is increasing, much of the data are from small case series, bringing into question their reliability and how easily they can be generalized to different populations. Conflicting results on which mutations are diagnostic of cHCC-CC need to be clarified. Further studies to evaluate the significance of genetic and signaling pathway mutations may lead to a better understanding of pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets.

Molecular biology

The molecular profile of cHCC-CCs remains incompletely characterized. Woo et al performed gene expression profiling on HCC, CC, and cHCC-CC human samples identifying a subtype of HCC with CC traits, which was associated with worse survival outcomes and suggesting a phenotypical overlap between HCC, CC, and cHCC-CC.Citation55 Coulouarn et al profiled 20 tissue samples of histologically confirmed cHCC-CC showing that it has stem cell progenitor features and is characterized by a downregulation of an HNF4-driven hepatocyte differentiation program and a commitment to the biliary lineage. Activation of TGFβ and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways was also observed.Citation56 TGFβ pathway is known to be involved in biliary differentiation and in epithelial-mesenchymal transition, whereas Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays a key role in regulating the fate of hepatoblasts toward a biliary ductal morphogenesis.Citation57,Citation58 Furthermore, integrative genomic analysis in the same study demonstrated that cHCC-CC shares common characteristics with a subset of HCC with stem cell traits.Citation56

However, genome-wide allelotyping of classical cHCC-CC, by Cazals-Hatem et al, showed that these tumors exhibit high level of chromosomal instability and are genetically closer to CC than to HCC.Citation14 A more recent comprehensive molecular characterization of cHCC-CCs was performed on 18 human tissue samples suggesting that they represent a heterogeneous group of tumors, which can be categorized into two main subclasses: 1) the classical subclass, which shares components of both HCC and CC arising from a common clonal origin, and 2) the stem cell subclass, which is associated with a progenitor-like phenotype and a more aggressive behavior. The latter is characterized by upregulation of proliferative signaling pathways (MYC, mTORC, and NOTCH). Interestingly, in this study, the CLC carcinoma was found to be a distinct entity with a biliary molecular profile and no HCC traits. It is characterized by chromosomal stability and active TGFβ signaling.Citation34

Therapeutic interventions

Surgery

Surgical resection is the only curative option for patients with cHCC-CC. The feasibility of surgery is dictated by several factors including patient’s overall physical condition, the extent of the tumor, and anatomical characteristics. The aim is to completely excise the lesion with clear margins and the least possible impact on the liver function, as significant liver impairment is associated with poor survival outcomes.Citation25

cHCC-CCs demonstrate characteristics of both tumors, showing hepatic and portal venous infiltration similar to HCC and also metastasizing to the lymph nodes on a similar pattern to CC. Therefore, major hepatic resection with hilar node dissection remains the recommended treatment in noncirrhotic patients with no distant metastases.Citation59 In cases of liver cirrhosis, limited resection may be considered to maintain adequate residual liver function.Citation25 The additional benefit of lymphadenectomy in the overall survival (OS) remains a controversial issue.Citation60–Citation62 Despite the risks and the complexity of major liver resection, fit patients with noncirrhotic liver have been found to tolerate it well.Citation63 A recent study suggested that in patients with similar tumor characteristics, age should not be considered a limiting factor for aggressive liver surgery as both investigated age groups had similar survival outcomes.Citation64 However, it should be taken into account that an age cut-off of 60 years was used for patient stratification in this study with the elderly patients having a mean age of 67.5 years and the younger 47 years. In patients with multiple comorbidities or liver cirrhosis, aggressive liver surgery could be detrimental; therefore, careful selection of the optimal surgical candidates is of paramount importance. The Child-Turgotte-Pugh and the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease scores have been used as predictors of postoperative mortality post liver resection. The latter is calculated from serum bilirubin, creatinine, and the international normalized ratio and has been preferable due to its more objective variables.Citation65,Citation66

Despite the curative aim of liver resection, cHCC-CC shows an aggressive behavior with high recurrence rates and an average 5-year survival rate of 30%.Citation16,Citation17,Citation30 The majority of studies so far have demonstrated worse postsurgical survival outcomes for patients with cHCC-CC compared to those with HCC but better than CC;Citation3,Citation11,Citation16,Citation17 however, in some cases, surgical outcomes were even worse than those for CC.Citation12,Citation15 This behavior could be underpinned by the distinct biological features of cHCC-CC, which need to be further elucidated.

Liver transplantation

The role of LT as a potential treatment option for cHCC-CC has been investigated in a number of studies limited by their retrospective nature, their small patient numbers, and also by the fact that, in the majority of cases, final diagnosis of cHCC-CC was only established postoperatively. Groeschl et al performed a retrospective analysis of the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database identifying 1,147 patients with HCC and 19 with cHCC-CC and compared survival outcomes after LT. They observed that patients with cHCC-CC had inferior 5-year OS rates compared to those with HCC (48% vs 78%, P=0.01).Citation67 Similarly, Garancini et al interrogated the SEER database identifying 465 patients with cHCC-CC who had undergone minor or major hepatectomy, or LT. Survival outcomes post LT were again less favorable than for patients with HCC (41.1% vs 67%, P<0.001). LT did not offer a survival benefit compared to major hepatectomy (MJH) and minor hepatectomy (MNH) in the multivariate analysis (HR: 0.28, 0.25, 0.29, respectively); therefore, they questioned the efficacy of LT and supported MJH as the optimal treatment approach for cHCC-CC.Citation18 The inferiority of LT in cHCC-CC patients was further supported by Vilchez et al, in their analysis of the united network for organ sharing (UNOS) database. They found a 5-year OS of 40% in cHCC-CC patients compared to 62% in HCC patients (P=0.002).Citation68 Park et al, in their retrospective analysis of 15 patients who underwent LT with a pretransplant diagnosis of HCC, reported that cHCC-CC was associated with high relapse rates within the first year.Citation69

Several smaller case studies have also been published with none conferring a clear benefit of LT to hepatic resection in this patient population.Citation19,Citation70–Citation73 Magistri et al performed a systematic review of the literature to address the same question, concluding that LT should not be considered for the management of cHCC-CC.Citation74 Considering all published evidence to date, major hepatic resection remains the best treatment option for resectable cHCC-CC. The role of LT in this tumor type is yet to be defined with more studies and better patient selection.

Nonsurgical treatment options

In cases of inoperable or recurrent cHCC-CCs, there are nonsurgical treatment options, which include transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), radioembolization, hepatic arterial infusional chemotherapy, ablative therapies, and systemic chemotherapy.Citation25

Limited data exist on the efficacy and benefits of liver-directed therapies. A small retrospective study evaluated survival outcomes in 18 patients with inoperable cHCC-CC who received liver-directed therapy (TACE, radioembolization, or hepatic arterial infusional chemotherapy) from a total cohort of 79 patients.Citation75 Those receiving liver-directed treatment had larger tumors than those undergoing surgical treatment (mean tumor size 8.9 vs 5.8 cm), more frequent satellite lesions (83% vs 32%), and higher incidence of lymph node metastases (33% vs 8%). Liver-directed therapy resulted in an overall partial response rate of 47% (50% with radioembolization, 20% with TACE, and 66% with hepatic arterial infusional chemotherapy) with median progression-free survival and OS of 8.3 and 16.0 months, respectively. Despite being limited by its retrospective nature and the small number of patients, this study demonstrates that liver-directed treatments could offer a survival benefit and potentially downstage patients for surgical treatment.Citation75 However, more research is needed to further support the validity of these outcomes.

TACE has been the mainstay for palliative management of HCC, and its efficacy is highly dependent on tumor vascularity due to the intravascular delivery of the embolic and chemotherapeutic agents. However, due to the histological heterogeneity of cHCC-CCsCitation76 and the fact that they are usually more fibrotic and less vascular than HCCs, the benefit of TACE is debatable. The efficacy of TACE on primary nonresectable and recurrent cHCC-CCs was investigated in two small retrospective studies, concluding that response and consequently prognosis are highly related to tumor vascularity. Survival outcomes were poorer than those seen for patients with HCC.Citation26,Citation77

Systemic chemotherapy

A standard treatment has not yet been established for advanced nonresectable cHCC-CCs, and the role of systemic chemotherapy remains unclear and associated with unfavorable outcomes.Citation75,Citation78,Citation79 Due to the rarity of this tumor, current evidence is limited and relies on case reports and small retrospective studies, while treatment decisions are extrapolated from HCC and CC.Citation80,Citation81 A recent multicenter retrospective analysis involving 36 patients evaluated several first-line treatments including gemcitabine/cisplatin, fluorouracil/cisplatin, and sorafenib and showed poorer OS upon treatment with sorafenib mono-therapy than for treatment with platinum-containing regimens (HR: 15.83 [95% CI 2.25–111.43], P=0.006). In this study, patients had an OS of 8.9 months across all treatments.Citation78 In their retrospective analysis of seven patients, Rogers et al showed similar survival outcomes (median OS: 8.3 months) and supported the lack of efficacy of sorafenib in this tumor type. Disease control was achieved in three patients who received gemcitabine plus platinum with or without bevacizumab as first or second line of treatment.Citation79

It is of interest that cHCC-CCs do not seem to respond to systemic treatments that are effective in the two separate malignancies, which underlines the discrete entity of these tumors. Platinum-containing regimens such as gemcitabine and cisplatin seem to be more promising among other available treatments; however, prospective trials are needed to identify a standard of care for unresectable cHCC-CCs.

Future perspectives

The failure of standard surgical and systemic treatments to tackle these phenotypically heterogeneous tumors requires new approaches for their optimal management. With the advent of omics and their integration in translational research, dissecting the mutational landscape of cHCC-CCs in view of developing molecularly targeted treatments should be a tangible goal. A great step toward this goal has been the successful development of primary liver cancer-derived organoids, which retain the histological characteristics and the genomic landscape of the original tumor.Citation82 These can be utilized not only for the identification of novel biomarkers but also for the screening of potential molecular targeted treatments. Of note is the identification of ERK inhibition as a potential target in a subset of HCC and CC patients. The use of organoids could revolutionize the biomarker discovery and drug testing for cHCC-CCs leading to novel treatments in the near future.

Furthermore, promising data stemming from ongoing clinical trials on HCC investigating several combinations of immunotherapy agents and the combination of immunotherapy with liver ablation indicate that this could be a potential therapeutic avenue to be explored also for cHCC-CCs.Citation83,Citation84

Conclusion

cHCC-CC is a rare, aggressive primary liver malignancy with poorer prognosis than HCC and CC. An accurate preoperative diagnosis is of key importance for its optimal management. However, this aspect remains a significant challenge due to the heterogeneity of its clinical and demographic features, indistinct imaging characteristics as well as the inconsistent application of histopathological criteria. The combination of imaging along with serum levels of tumor markers raise the suspicion of cHCC-CC, but tumor biopsies are required for a definite diagnosis. The final diagnosis of cHCC-CC is based on immunohistopathology and can be facilitated by genetic analyses. There is ongoing progress in the identification of the mutational landscape of cHCC-CC, which can further characterize these tumors and result in the development of new targeted treatment. Continued research is required to define the roles of both advanced imaging and molecular analysis in the diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms of cHCC-CC. Major hepatec-tomy and hilar lymph node resection remain the standard of care in operable disease. LT has not been found to be of benefit in cHCC-CC; however, more clinical data are required to obtain a conclusive outcome. Similarly, the role of liver-directed therapies and systemic treatment remains limited and needs to be further investigated in the context of prospective clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

Pictures kindly provided by Dr Rosa Miquel, consultant histopathologist, Liver Histopathology Laboratory, King’s College Hospital.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- GoodmanZDIshakKGLanglossJMSesterhennIARabinLCombined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. A histologic and immunohistochemical studyCancer19855511241352578078

- BosmanFTCarneiroFHrubanRTheiseNDWHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive SystemIARC PressLyon2010

- KohKCLeeHChoiMSClinicopathologic features and prognosis of combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinomaAm J Surg2005189112012515701504

- AllenRALisaJRCombined liver cell and bile duct carcinomaAm J Pathol194925464765518152860

- WachtelMSZhangYXuTChiriva-InternatiMFrezzaEECombined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinomas; analysis of a large databaseClin Med Pathol20081S500S547

- JarnaginWRWeberSTickooSKCombined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: demographic, clinical, and prognostic factorsCancer20029472040204611932907

- BruntEAishimaSClavienPAcHCC-CCA: consensus terminology for primary liver carcinomas with both hepatocytic and cholangiocytic differentiationHepatology201868111312629360137

- WangAQZhengYCDuJCombined hepatocellular cholan-giocarcinoma: controversies to be addressedWorld J Gastroenterol201622184459446527182157

- KimHParkCHanKHPrimary liver carcinoma of intermediate (hepatocyte–cholangiocyte) phenotypeJ Hepatol200440229830414739102

- ZhangFChenXPZhangWCombined hepatocellular chol-angiocarcinoma originating from hepatic progenitor cells: immuno-histochemical and double-fluorescence immunostaining evidenceHistopathology200852222423218184271

- LeeWSLeeKWHeoJSComparison of combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma with hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomaSurg Today2006361089289716998683

- ZuoHQYanLNZengYClinicopathological characteristics of 15 patients with combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocar-cinomaHepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int20076216116517374575

- LeeCHHsiehSYChangCJLinYJComparison of clinical characteristics of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma and other primary liver cancersJ Gastroenterol Hepatol201328112212723034166

- Cazals-HatemDRebouissouSBioulac-SagePClinical and molecular analysis of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinomasJ Hepatol200441229229815288479

- LeeJHChungGEYuSJLong-term prognosis of combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma after curative resection comparison with hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinomaJ Clin Gastroenterol2011451697520142755

- YoonYIHwangSLeeYJPostresection outcomes of combined hepatocellular carcinoma-cholangiocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomaJ Gastrointest Surg201620241142026628072

- YinXZhangBHQiuSJCombined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma: clinical features, treatment modalities, and prognosisAnn Surg Oncol20121992869287622451237

- GaranciniMGoffredoPPagniFCombined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: a population-level analysis of an uncommon primary liver tumorLiver Transpl201420895295924777610

- JungDHHwangSSongGWLongterm prognosis of combined hepatocellular carcinoma-cholangiocarcinoma following liver transplantation and resectionLiver Transpl201723333034128027599

- NgIOShekTWNichollsJMaLTCombined hepatocellular-chol-angiocarcinoma: a clinicopathological studyJ Gastroenterol Hepatol199813134409737569

- GhouriYAMianIRoweJHReview of hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, etiology, and carcinogenesisJ Carcinog2017161128694740

- SanyalAJYoonSKLencioniRThe etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma and consequences for treatmentOncologist201015Suppl 4142221115577

- KhanSAToledanoMBTaylor-RobinsonSDEpidemiology, risk factors, and pathogenesis of cholangiocarcinomaHPB2008102778218773060

- TaguchiJNakashimaOTanakaMHisakaTTakazawaTKojiroMA clinicopathological study on combined hepatocellular and cholan-giocarcinomaJ Gastroenterol Hepatol19961187587648872774

- KassahunWTHaussJManagement of combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinomaInt J Clin Pract20086281271127818284443

- KimJHYoonHKKoGYNonresectable combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of the response and prognostic factors after transcatheter arterial chemoembolizationRadiology2010255127027720308463

- AokiKTakayasuKKawanoTCombined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma: clinical features and computed tomographic findingsHepatology1993185109010957693572

- YanoYYamamotoJKosugeTCombined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 26 resected casesJpn J Clin Oncol200333628328712913082

- BhagatVJavleMYuJCombined hepatocholangiocarcinoma: case-series and review of literatureInt J Gastrointest Cancer2006371273417290078

- TickooSKZeeSYObiekweSCombined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: a histopathologic, immunohistochemical, and in situ hybridization studyAm J Surg Pathol200226898999712170085

- YehMMPathology of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinomaJ Gastroenterol Hepatol20102591485149220796144

- TheiseNDYaoJLHaradaKHepatic “stem cell” malignancies in adults: four casesHistopathology200343326327112940779

- WuPCFangJWLauVKLaiCLLoCKLauJYClassification of hepatocellular carcinoma according to hepatocellular and biliary differentiation markers. Clinical and biological implicationsAm J Pathol19961494116711758863666

- MoeiniASiaDZhangZMixed hepatocellular cholangiocar-cinoma tumors: cholangiolocellular carcinoma is a distinct molecular entityJ Hepatol201766595296128126467

- FujiiHZhuXGMatsumotoTGenetic classification of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinomaHum Pathol20003191011101711014564

- YanoHIemuraAHaramakiMA human combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma cell line (KMCH-2) that shows the features of hepatocellular carcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma under different growth conditionsJ Hepatol19962444134228738727

- MaedaTAdachiEKajiyamaKSugimachiKTsuneyoshiMCombined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: proposed criteria according to cytokeratin expression and analysis of clinicopathologic featuresHum Pathol19952699569647545644

- O’ConnorKWalshJCSchaefferDFCombined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma (cHCC-CC): a distinct entityAnn Hepatol201413331732224756005

- GeraSEttelMAcosta-GonzalezGXuRClinical features, histology, and histogenesis of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinomaWorld J Hepatol20179630030928293379

- ChoiBIHanJKKimYICombined hepatocellular and cholan-giocarcinoma of the liver: sonography, CT, angiography, and iodized-oil CT with pathologic correlationAbdom Imaging199419143468161902

- MaximinSGaneshanDMShanbhogueAKCurrent update on combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinomaEur J Radiol Open20141404826937426

- SammonJFischerSMenezesRMRI features of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma versus mass forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomaCancer Imaging2018181829486800

- FowlerKJSheybaniAParkerRA3rdCombined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma (biphenotypic) tumors: imaging features and diagnostic accuracy of contrast-enhanced CT and MRIAm J Roent-genol20132012332339

- WellsMLVenkateshSKChandanVSBiphenotypic hepatic tumors: imaging findings and review of literatureAbdom Imaging20154072293230525952572

- ParkSHLeeSSYuECombined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI findings correlated with pathologic features and prognosisJ Magn Reson Imaging201746126728027875000

- SanadaYShiozakiSAokiHTakakuraNYoshidaKYamaguchiYA clinical study of 11 cases of combined hepatocellular–cholangiocarcinoma: assessment of enhancement patterns on dynamics computed tomography before resectionHepatol Res200532318519515978872

- JeonSKJooILeeDHCombined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma: LI-RADS v2017 categorisation for differential diagnosis and prognostication on gadoxetic acid-enhanced MR imagingEur Radiol Epub2018628

- PotretzkeTATanBRDoyleMBBruntEMHeikenJPFowlerKJImaging features of biphenotypic primary liver carcinoma (hepatochol-angiocarcinoma) and the potential to mimic hepatocellular carcinoma: LI-RADS analysis of CT and MRI features in 61 casesAm J Roentgenol20162071253126866746

- HeCMaoYWangJThe Predictive value of staging systems and inflammation scores for patients with combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma after surgical resection: a retrospective studyJ Gastrointest Surg20182271239125029667093

- YouHLWengSWLiSHCopy number aberrations in combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinomaExp Mol Pathol201292328128622366251

- LiuZHLianBFDongQZWhole-exome mutational and transcriptional landscapes of combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma reveal molecular diversityBio-chim Biophys Acta186420186 Pt B23602368

- XueTCZhangBHYeSLRenZGDifferentially expressed gene profiles of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma by integrated microarray analysisTumor Biol201536858915899

- SasakiMSatoYNakanumaYMutational landscape of combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma, and its clinico-pathological significanceHistopathology201770342343427634656

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Research NetworkComprehensive and integrative genomic characterization of hepatocellular carcinomaCell2017169713271341.e2328622513

- WooHGLeeJHYoonJHIdentification of a cholangiocarcinoma-like gene expression trait in hepatocellular carcinomaCancer Res20107083034304120395200

- CoulouarnCCavardCRubbia-BrandtLCombined hepa-tocellular-cholangiocarcinomas exhibit progenitor features and activation of Wnt and TGFbeta signaling pathwaysCarcinogenesis20123391791179622696594

- DecaensTGodardCde ReynièsAStabilization of beta-catenin affects mouse embryonic liver growth and hepatoblast fateHepatology200847124725818038450

- TanXYuanYZengGBeta-catenin deletion in hepatoblasts disrupts hepatic morphogenesis and survival during mouse developmentHepatology20084751667167918393386

- KimKHLeeSGParkEHSurgical treatments and prognoses of patients with combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarci-nomaAnn Surg Oncol200916362362919130133

- NakamuraSSuzukiSSakaguchiTSurgical treatment of patients with mixed hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinomaCancer1996788167116768859179

- SasakiAKawanoKAramakiMClinicopathologic study of mixed hepatocellular and cholangiocellular carcinoma: modes of spreading and choice of surgical treatment by reference to macroscopic typeJ Surg Oncol2001761374611223823

- ErcolaniGGraziGLRavaioliMThe role of lymphadenectomy for liver tumors: further considerations on the appropriateness of treatment strategyAnn Surg2004239220220914745328

- BismuthHMajnoPEHepatobiliary surgeryJ Hepatol2000321 Suppl20822410728806

- TaoCYLiuWRJinLSurgical treatment of combined hepato-cellular-cholangiocarcinoma is as effective in elderly patients as it is in younger patients: a propensity score matching analysisJ Cancer2018961106111229581790

- NorthupPGWanamakerRCLeeVDAdamsRBBergCLModel for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) predicts nontransplant surgical mortality in patients with cirrhosisAnn Surg2005242224425116041215

- MalinchocMKamathPSGordonFDPeineCJRankJTer BorgPCA model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shuntsHepatology200031486487110733541

- GroeschlRTTuragaKKGamblinTCTransplantation versus resection for patients with combined hepatocellular carcinoma-cholangiocarci-nomaJ Surg Oncol2013107660861223386397

- VilchezVShahMBDailyMFLong-term outcome of patients undergoing liver transplantation for mixed hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma: an analysis of the UNOS databaseHPB2016181293426776848

- ParkYHHwangSAhnCSLong-term outcome of liver transplantation for combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinomaTranspl Proc201345830383040

- SongSMoonHHLeeSComparison between resection and transplantation in combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinomaTranspl Proc201345830413046

- BergquistJRGroeschlRTIvanicsTMixed hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: a rare tumor with a mix of parent phenotypic characteristicsHPB2016181188689227546172

- MagantyKLeviDMoonJCombined hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: outcome after liver transplantationDig Dis Sci201055123597360120848202

- WuCHYongCCLiewEHCombined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma: diagnosis and prognosis after resection or transplantationTranspl Proc201648411001104

- MagistriPTarantinoGSerraVGuidettiCBallarinRdi BenedettoFLiver transplantation and combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: feasibility and outcomesDig Liver Dis201749546747028258929

- FowlerKSaadNEBruntEBiphenotypic primary liver carcinomas: assessing outcomes of hepatic directed therapyAnn Surg Oncol201522134130413726293835

- de VitoCSarkerDRossPHeatonNQuagliaAHistological heterogeneity in primary and metastatic classic combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: a case seriesVirchows Archiv2017471561962928707055

- NaSKChoiGHLeeHCThe effectiveness of transarterial chemoembolization in recurrent hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma after resectionPLoS One2018136e019813829879137

- KobayashiSTerashimaTShibaSMulticenter retrospective analysis of systemic chemotherapy for unresectable combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinomaCancer Sci201810982549255729856900

- RogersJEBolonesiRMRashidASystemic therapy for unresectable, mixed hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: treatment of a rare malignancyJ Gastrointest Oncol20178234735128480073

- ChiMMikhitarianKShiCGoffLWManagement of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: a case report and literature reviewGastrointest Cancer Res20125619920223293701

- KimGMJeungH-CKimDA case of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma with favorable response to systemic chemotherapyCancer Res Treat201042423523821253326

- BroutierLMastrogiovanniGVerstegenMMHuman primary liver cancer-derived organoid cultures for disease modeling and drug screeningNat Med201723121424143529131160

- SprinzlMFGallePRCurrent progress in immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinomaJ Hepatol201766348248428011330

- DuffyAGUlahannanSVMakorova-RusherOTremelimumab in combination with ablation in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinomaJ Hepatol201766354555127816492

- LiuCLFanSTLoCMHepatic resection for combined hepato-cellular and cholangiocarcinomaArch Surg20031381869012511158