Abstract

Background

Health care organizations are utilizing quality and safety (QS) teams as a mechanism to optimize care. However, there is a lack of evidence-informed best practices for creating and sustaining successful QS teams. This study aimed to understand what health care leaders viewed as barriers and facilitators to establishing/implementing and measuring the impact of Canadian acute care QS teams.

Methods

Organizational senior leaders (SLs) and QS team leaders (TLs) participated. A mixed-methods sequential explanatory design included surveys (n=249) and interviews (n=89). Chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare categorical variables for region, organization size, and leader position. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed for constant comparison analysis.

Results

Five qualitative themes overlapped with quantitative data: (1) resources, time, and capacity; (2) data availability and information technology; (3) leadership; (4) organizational plan and culture; and (5) team composition and processes. Leaders from larger organizations more often reported that clear objectives and physician champions facilitated QS teams (p<0.01). Fewer Eastern respondents viewed board/senior leadership as a facilitator (p<0.001), and fewer Ontario respondents viewed geography as a barrier to measurement (p<0.001). TLs and SLs differed on several factors, including time to meet with the team, data availability, leadership, and culture.

Conclusion

QS teams need strong, committed leaders who align initiatives to strategic directions of the organization, foster a quality culture, and provide tools teams require for their work. There are excellent opportunities to create synergy across the country to address each organization’s quality agenda.

Introduction

Quality improvement initiatives are extensively used across health care; however, disappointing outcomes from these initiatives remain troublesome for health care professionals and researchers alike.Citation1 In light of this quality chasm, quality and safety (QS) teams have been offered as a collaborative strategy to achieve better alignment between care offered and population needs.Citation2–Citation5 Also termed project or quality improvement teams,Citation6 QS teams are groups of individuals brought together in efforts to improve the quality of care (ie, efficiency, effectiveness, accessibility, patient-centeredness, safety, timeliness).Citation7–Citation9 Members include health professionals and support staff who identify factors impeding safe health care delivery, and subsequently develop and implement actions to address concerns in their clinical area.

While QS teams are being widely applied, reviews of the literature show little evidence for their efficacy or evidence-based recommendations for creating or sustaining highly effective QS teams.Citation6,Citation7,Citation10,Citation11 Compared to interdisciplinary care delivery and management teams largely discussed within health care teams and teamwork literature,Citation6,Citation12,Citation13 QS teams implement more complex initiatives requiring organizational change. QS teams are not equally effective even when working on the same initiative and using the same quality improvement methodology, as in the case of teams within quality improvement collaboratives.Citation14–Citation16 This suggests that research should focus on detailing the strategies used to facilitate uptake of practices (ie, educational workshops, academic detailing, audit and feedback),Citation17,Citation18 as well as understanding contextual barriers and factors that encourage well-functioning and innovative teams.Citation11,Citation12,Citation19

Within the Canadian context, there are few studies about QS teams and fewer that detail the influence of broader contextual factors. To better understand QS teams across Canada, we conducted a large descriptive study of organizational senior leaders (SLs) and QS team leaders (TLs) to understand how leaders viewed and stewarded quality and QS teams in their organizations. The purpose of this paper is to present key findings about the contextual factors that act as barriers and facilitators to establishing/implementing and measuring the impact of QS teams, and explore potential differences in perspectives across the country. Specifically, we were interested in differences as a result of leadership position (SL, leader of QS team), region, and organization size. The implications of this paper extend beyond Canada, providing decision makers with factors in most immediate need of intervention to improve QS in their organizations.

Methods

Design

This multiphase study used a mixed-methods sequential explanatory designCitation20 and included national online surveys followed by semi-structured interviews with SLs and QS TLs in Canadian hospitals. A mixed-methods design was selected for significance enhancement,Citation21 that is, to achieve an in-depth understanding of study findings through augmenting quantitative findings with the richness of qualitative data.Citation22

Participants and recruitment

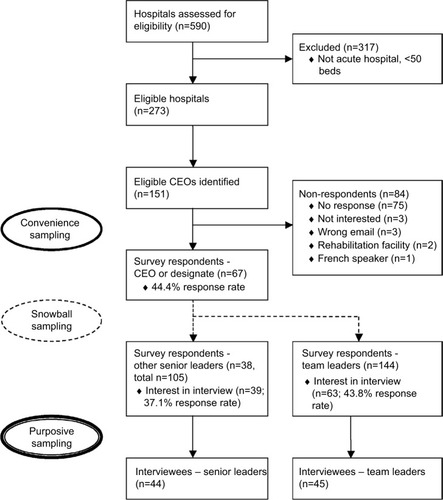

The study was advertised through the Canadian Patient Safety Institute newsletter 8 weeks prior to the first phase of recruitment. We identified all Canadian chief executive officers (CEOs) of organizations/regions that included an acute care hospital with >50 beds.Citation23,Citation24 From publicly available information provided by the hospital or health region, 151 CEOs were invited to participate in the study through a personal email from the research team describing the study; they were asked to forward the email and attachments to other appropriate SLs and TLs, from within their organization, who were involved in QS teams (ie, snowball sampling; presents flow diagram). Email reminders were sent to nonresponders at 2-week and 4-week intervals to optimize response rate.Citation25 At the end of the survey, all participants were asked to provide their contact information if interested in an interview. From the 102 participants who offered to be interviewed, purposive sampling was then used to assure that key informants were selected from hospitals of different sizes (<500 beds, >500 beds), academic status (teaching, non-teaching, both), and from different geographic regions. These regions were categorized according to the Accreditation Canada formatCitation26 (West – British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Northwest Territories; East – New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island; Ontario). It is important to note that SLs responded on behalf of their organization, while TLs responded from a single-team perspective.

Data collection

Data were collected between March and July 2010. The online survey items and semi-structured interview questions were generated through a scoping review,Citation7 expert review by health service researchers and decision makers, and a pilot study. In the pilot study, the online survey was given to SLs and TLs to assess face validity, optimize completeness of survey items, and test the study website. These same individuals participated in pilot interviews, and the results of these were used to refine the interview guide and develop a provisional qualitative coding framework.

Online survey

Thirty-three items assessed facilitators and barriers to (1) establishing and implementing QS team initiatives, and (2) measuring the impact of initiatives. Responses were measured using a checkbox to indicate the presence of the facilitator or barrier. Two additional open-ended items asked participants to describe other facilitators and barriers that were not identified in the survey. The survey also included questions regarding demographic and organizational characteristics, such as position, professional designation, location, setting, and academic status.

Interviews

Telephone interviews were conducted by the principal investigator (DW), an experienced qualitative researcher. Interviews were digitally recorded and lasted 60 minutes. Interviewees were asked in-depth questions about the challenges and facilitators in implementing their teams and measuring the impact of the teams. Each participant’s survey data was reviewed by the interviewer prior to each interview and was used to probe for a richer understanding about his/her survey responses. Interviewer notes were also documented. Sampling continued to data saturation across regions, organizational size, and leader type.

Data analysis

The data generated from this study were analyzed using a mixed-methods data analysis process.Citation21 Data reduction, display, and transformation were conducted independently for survey and interview data. Data comparison and integration were achieved by combining both qualitative and quantitative data.

Data from the online survey were downloaded into an Excel database, and subsequently analyzed using the statistical package SAS 9.2. Survey results were summarized via descriptive statistics. Frequency distributions were used to identify and correct data entry errors, and to explore the array of answers to each question. Univariate statistics including chi-squared and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare categorical variables for region, organization size, and type of leader (SL, TL). A significance level of .05 was used; however, a conservative significance level of <.01 was used to account for post hoc multiple comparisons in regions.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, and imported into NVivo 8 for qualitative data storage, indexing, and theorizing.Citation27,Citation28 From our pilot interviews, the authors (DW, KJ, JN) and a research assistant developed a provisional coding framework to facilitate thematic analysis.Citation29 Starting after the first interview, the team independently coded all interviews by examining and assigning text to codes. Biweekly meetings during data analysis facilitated a negotiated and refined coding framework for constant comparsionCitation30 between themes within a single interview (open coding) and across interviews (axial coding), and discrepant and negative information. To establish an audit trail, coding team discussions, coding definitions, and rationale for changes to the coding framework were documented. Matrices of the themes were created to understand theme interrelationships and cross-validation of the data. To assure reliability, 20% of the interviews were coded by two coders, and a coding comparison indicated 85–90% agreement. Memos were also used to record researcher’s comments and insights, contributing to analysis.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was secured from the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board, the University of Saskatchewan Biomedical Research Ethics Board, and the Atlantic Health Sciences Corporation Research Services. Consent was implied through submission of the online survey, and all interview participants provided written informed consent.

Results

Sample

Two hundred and forty-nine surveys and 89 interviews were completed (). The survey response rate for the CEO or a designate from his/her organization was 44.4%. Snowball sampling did not permit further response rate calculations for other SLs and TLs who were not the first point of contact. CEO/designate survey respondents and nonrespondents did not differ significantly by their organization’s overall or acute care bed size, hospital teaching status, or provincial/regional grouping. In total, 67 CEOs/designates, 38 other SLs, and 144 TLs responded to the survey.

Table 1 Distribution of survey and interview participants by region, N (%)

Academic status (teaching, n=30; nonteaching, n=31; both, n=40) and number of acute care beds in the organization (<100, n=39; 100–299, n=14; 300–499, n=22; 500–999, n=4; >1000, n=20) were distributed evenly across CEO/designate respondents’ organizations (). Ninety-two SLs reported having a quality and/or safety portfolio/department in their organization. SLs who completed the survey primarily included CEOs and vice presidents. TLs also included senior executives and directors, in addition to other positions. TL professional designations included a large proportion of registered nurses and allied health professionals (eg, physiotherapists, psychologists), and several physicians and pharmacists. Almost half of SLs were responsible for one hospital, and roughly one-third of TLs participated on a single team.

Table 2 Characteristics of senior leader and team leader survey respondents, N (%)

Interviewees included CEOs (n=13), other senior executives (n=31), directors, managers, or coordinators (n=19), medical staff (n=3), quality and/or safety personnel (n=21), and other staff positions (n=11). TL interviewees included nurses (n=20), physicians (n=5), allied health professionals (n=10), and others (n=9).

Facilitators and barriers of QS teams

Regional differences in facilitators and barriers are reported in and . Some factors were highlighted simultaneously as a barrier and facilitator. Five themes from the qualitative analysis overlapped with quantitative data, and are integrated below: (1) resources, time, and capacity; (2) data availability and information technology (IT); (3) leading across the organization; (4) organizational plan and culture; and (5) team composition and processes. A purposeful selection of quotes that augment the quantitative findings are presented as follows.

Table 3 Facilitators and barriers to establishing/implementing QS teams, N (%)

Table 4 Facilitators and barriers to measuring the impact of QS teams, N (%)

Resources, time, and capacity

Survey respondents expressed that insufficient financial (48.6%) and human resources (49.8%) were barriers to establishing/implementing QS teams, while a lack of financial resources hindered evaluating their work (45.0%). In an interview, one SL expressed, “We are not resourced to continue to measure for every quality improvement project.” Financial resources were linked to insufficient infrastructure, data system, and human resources.

So if people want these things measured, then they need to provide the resources to actually measure […] but there aren’t enough people and resources to be able to actually do all these things. [TL West 2.1.14]

Participants identified the importance of access to expertise, “time to do the work,” and “to be able to support getting people away from their daily work to focus on quality.” In particular, 60.2% of survey respondents voiced a lack of time to meet with team, although this was less often reported by TLs than SLs (54.2% vs. 68.6%, p<.001). When discussed as a facilitator, time to meet with the team was identified more so by TLs (45.8%) than SLs (25.7%, p<.001).

I think that it is important that we have dedicated resources. People on the frontlines with whites of the patients’ eyes demanding time need to have somebody with the skills and capacity to support them in this work. They want to do it but they can’t fit it into their workload. [TL West 1.4.1]

Participants extended their description of resources to include organizational investment in building capacity across the whole organization, within teams, and “inside the programs right at the unit level.” While staff are expected to “be doing [quality work],” they need to have “the tools and the templates and ad hoc advice” as well as “a basket of skills that allows them to analyze their work” so that they can “make some decisions about how they can improve.” Participants emphasized that all people within the organization need to be held accountable for QS. For example, one SL stated:

We trained the staff and while it was being rolled out on the unit, these were the people who supported the staff in their practice. We want patient safety champions on each unit. We want to build capacity through the organization […] and then give people the data to look at on a regular basis so they can actually respond to it themselves. [Ontario 71.0]

Expertise in evaluation and expertise in statistics were viewed as facilitators (55.8%, 44.6%), while the lack thereof acted as barriers to measurement (35.3%, 40.2%). Fewer TLs (45.1%) than SLs (70.5%, p<.001) reported evaluation expertise as a facilitator. It was further acknowledged that expertise was required at the unit (microsystem) and organization (macrosystem) level.

You need people that can understand that [statistics] and can articulate it. Not like statisticians, but unit managers and clinical leaders. [TL West 2.1.22]

Data availability and IT

Meaningful data were seen as helpful to engage stakeholders and “help them realize that their work is making a difference” by visibly tracking and communicating outcomes from QS team projects. Participants highlighted how having accessible real-time data and data systems (ie, data availability=66.7%) with appropriate IT (46.2%) was crucial to support planning and evaluation, without which “teams cannot be successful.”

However, data availability was a challenge as there seemed to be a constant struggle between what should and could be measured: “we know there’s indicators we’d like to collect or report on, but we can’t get the data for it. Our board wants to see the indicator […] to see trends […] and how we compare provincially and nationally” [SL East 1.7.0]. Data availability (48.6%) and IT (45.0%) were top barriers reported for measuring team impact, and together were a barrier to establishing/implementing teams (35.7%). For some, the technology to drive data collection was either not available or inadequate:

[Technology is] always a struggle for us. We do not have an electronic health record. We don’t have a business intelligence tool, but we’re moving towards that. So a lot of the work that we do on the quality front is still manually driven, so it’s pretty labour intensive. [SL East 1.3.1]

Several participants described that they were “really at [their] infancy” in terms of measurement capacity, but were beginning to “expand [their] quality initiatives around measurement.” Fewer TLs (40.3%) than SLs (60.0%, p=.002) reported data availability as a barrier.

Leading across the organization

Participants emphasized various forms of leadership in facilitating QS team establishment/implementation (management/supervisory=80.3%; board/senior=71.9%) and measuring team impact (64.3%). Participants in Eastern provinces viewed board/senior leadership (51.7%) as less of a facilitator than participants in the West (76.9%, p=.001) or Ontario (79.0%, p<.001). While fewer TLs than SLs reported that leadership enables establishment/implementation (management/supervisory; 72.2% vs. 91.4%, p<.001) and measurement (54.2% vs. 78.1%, p<.001), respectively, this differentiation was not apparent across the interviews. Interviewees spoke to multiple levels of leadership (ie, governance/board, senior executive, manager, team/frontline), and that leaders “don’t just lead from the top. [They] lead from all directions and all layers in an organization” [SL Ontario 34.0]. Interviewees also discussed the roles of leaders, including the importance of setting the “vision,” establishing a “strategic approach” to the quality agenda, enabling and engaging staff in QS team initiatives, and creating and providing access to resources.

A number of interview participants identified the need for co-executive sponsors of teams as well as physician co-leads: “We know that where we’ve had some of our best results is where we’ve had strong physician involvement, and ideally, physician leadership. We’ve got a dyad leadership model here” [SL West 3.7.1]. These leadership positions were seen to support engagement of other important champions in QS teams: “It doesn’t matter how it happens; it’s useful to have champions within all corners of the organization and physicians especially because they are the gatekeepers” [TL West 1.4.1]. A lack of a physician champion (36.9%) was one of the top barriers to establishing/implementing QS teams, and emerged as a facilitator more often for larger (64.3%) than smaller organizations (36.8%, p=.007).

Organizational plan and culture

Participants discussed the importance of organizational goals and strategic plans (78.7%) to establishing/implementing QS teams. Several participants noted that their organizations were “requiring the teams to link their activity to the strategic plan of the organization […] identify how it’s tied to one of the strategic directions” [TL West 2.1.1]. Some participants felt that by aligning QS team initiatives with corporate priorities, resource allocation could be improved, and leaders’ responsibilities and accountabilities better clarified. How the vision was communicated and operationalized in the strategic plan influenced the culture of QS. As one TL noted, “I see where my project fits in into whole organizational identity. And I know how my work now contributes and I feel valued” [TL Ontario 34.1]. Culture was seen as interconnected to improvement efforts and the organization’s strategic direction. “The biggest barrier [can be] culture. Without a positive culture it’s very difficult to push the [quality agenda] forward” [SL West 1.1]. Overall, culture of the organization (63.9%) was identified as one of the top facilitators to establishing/implementing QS teams; however, more TLs than SLs reported the culture of the organization as a barrier (35.4% vs. 19.1%, p<.001).

Team composition and processes

Survey respondents saw team composition, specifically a multidisciplinary team (66.7%), as facilitating QS team establishment/implementation. Several interviewees emphasized multidisciplinary QS teams as being more successful than those with representation from a single discipline. Others expanded to include members “[who] have the knowledge and skills” and frontline professionals “closest to the activity […] to have some skin in the game to be able to come up with the solutions” [SL West 4.1.0].

While not apparent in the interviews, survey results revealed that more TLs than SLs reported communication between team members (54.2% vs. 31.4%, p<.001) as a facilitator to establishing/implementing QI teams. “There has to be […] open lines of communication and they have to have that ability to communicate” [SL East 1.3.3]. Having clear and defined objectives for initiatives emerged as a facilitator more often for larger organizations (69.0%) than smaller organizations (40.4%, p=.005).

Discussion

Health systems face unparalleled pressure to improve the quality and performance of their organizations. QS teams are being used as a mechanism to assist organizations in meeting the goals of their quality agenda. In this study, our aim was to understand the barriers and facilitators that SLs and TLs faced in establishing/implementing and measuring the impact of QS team initiatives, and explore differences across the country. Themes that emerged in our data reflect the important contextual factors identified in the Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ).Citation31 Across Canada, there were several significant differences by region, organization size, and leader position.

Resources, in particular time and expertise, were fundamental to QS team initiatives. Given that SLs’ perspectives reflect the accountability of multiple teams and other competing organizational priorities, it is not surprising that significantly more SLs than TLs viewed lack of time as a barrier. In their study of Canadian SLs of quality improvement and performance, Price Waterhouse CoopersCitation32 reported that a lack of capacity (ie, resources, skills) was a barrier to the success of quality improvement initiatives. Building QS capacity in QS teams requires targeted knowledge development and mentorship.Citation33 Baker et alCitation34 further highlight that investment in resources is the responsibility of individual organizations, and also a collective responsibility of governments at the local, provincial, and national level. To address resources, organizations need to consider the number of projects and collaborations within and outside the organization.

Similar to the recommendations of Curtis et al,Citation35 data and IT support enabled QS teams. Nearly half of respondents indicated that data availability was a barrier, and many felt that it was difficult for teams to create a sense of urgency and share the impact of the initiative if data were unavailable or translated in a manner not understandable to the end user. As Ferlie and ShortellCitation36 and othersCitation37,Citation38 note, successful quality improvement work requires infrastructure (eg, data systems, communication channels). Creating effective quality improvement collaborative is dependent on development of measurable targets and the feasibility of accomplishing these targets.Citation39 With organizational accountability for evidence of impact (ie, patient, provider, system outcomes), it is not unexpected that more SLs saw data availability as a barrier.

Across the organizational, team effectiveness, and quality improvement literature, leadership is central to creating and implementing changes required to advance the quality agenda of health care organizations.Citation40–Citation43 Taylor et alCitation44 suggest that strengthening primary care and the larger health system requires the commitment of primary care leaders as well as leadership in regulatory bodies and government to provide resources to support development of skills and knowledge. Our participants clearly spoke to the necessity of leadership at various levels. Critical to this transformation are skilled leaders across the organization who can catalyze high performance by engaging and energizing people to strive for this fundamental goal. Fewer participants in the East reported board and senior leadership as a facilitator of QS teams. During the time of the study, major restructuring was occurring in several Eastern provinces, where both regionalization and leadership were shifting and unstable. In comparison, we suggest that Ontario’s Excellent Care for All ActCitation45 guided organizational leaders in Ontario toward a clear commitment to quality in their own organization. This legislation has addressed how health care quality is defined, who is responsible and accountable for quality, how to support organizational capability to deliver quality of care, and how to make performance transparent to the public.

Quality improvement research has primarily focused on the role of physicians and SLs, and less work has included patient care managers at the operational level, who guide initiatives.Citation46 In our research, fewer TLs than SLs saw supervisors or management as enablers of QS teams, which may be the result of the direct influence of microsystem leadership on the work of teams. Supporting this claim, the MUSIQCitation31 hypothesizes a close relationship from microsystem leadership to QS team leadership, representing how the capacity for and support and involvement in improvement efforts by microsystem leaders impacts QS teams. While interprofessional team membership was important, many participants indicated that teams were more successful when physicians were involved and when physicians were leaders. There is an increasing recognition of the need for, and training of, physicians to lead quality initiativesCitation47–Citation51 and emerging evidence that high-performing organizations benefit from physician leadership.Citation37,Citation52 Almost twice as many participants from larger organizations compared with smaller organizations saw the facilitative role of physician champions. Physician involvement could be related to a number of potential factors to be explored in future work: incentives for participation, availability/accessibility of physicians, usage of physician coleaders in hospital structures, and alignment of QS team initiatives with physician practice and interest.Citation47

Advancing the quality agenda and organizational performance requires a vision set by SLs and the hospital board that makes the status quo uncomfortable, yet the future attainable.Citation53 Interviewees spoke of the importance of a vision and strategic plan in creating a learning and QS culture. More TLs viewed culture as a barrier to their work; TLs are faced with the reality of either a positive or negative culture in implementing initiatives at the microsystem level. Mills and WeeksCitation14 have found that QS teams that implement work aligned with organizational strategic priorities are more likely to be successful. Such alignment supports acquisition of resources and attention toward indicators and their measurement. In a study of 29 quality improvement teams, Versteeg et alCitation54 found that those teams that had more favorable organization conditions (ie, executive sponsorship, resources, inspirational and skilled leaders, a local and organizational climate for change) also had more favorable patient outcomes. Similarly, Carter et alCitation55 found that local and organizational context highly influenced success. For effective quality improvement, teams require supportive internal team structures and general organizational structure.Citation17 In this study, the organizational plan was interconnected with culture. Leaders experience a tension between local, organizational, and provincial priorities. Accordingly, focusing and aligning projects with strategic priorities will help with this balance. Clinical managers can play a key role in creating a climate and developing structures such as QS huddle rounds to identify in care processes or organizational practices requiring further improvement.Citation56

Like Santana et al’s study of successful quality improvement teams,Citation11 participants in this study expressed the need for a “diverse(ly) skilled” team to develop and execute improvement projects. Specifically, successful teams were seen as interprofessional (including a diversity of clinical and business representation) with emphasis on the necessary involvement of physicians and frontline staff with content and end-user knowledge. While this study did not explore this in depth, other literature emphasizes additional team dimensions known to effect performance, such as skills that enhance team member interactions (ie, team processes).Citation6,Citation57,Citation58 In their study of a quality improvement learning collaborative program in primary health care, Kotecha et alCitation59 reported improvement in interdisciplinary team functioning, specifically a better understanding and respect of roles, improved communication, and team collaboration. The finding that more TLs viewed communication between members as enabling their QS team is not unexpected given that necessity of communication to complete the tasks of the initiative. More participants from large organizations reported the importance of clear QS team objectives, which may be due to a larger number of projects and additional complexity in their structures and processes.

Canadian health care organizations are striving for excellence and are utilizing QS teams as a means to meeting the goals of their quality agenda. It is apparent from our national study that there are more similarities than differences with respect to the barriers and facilitators faced by QS teams. Tremendous opportunity exists to create synergy across the country through streamlining quality initiatives, pooling expertise and resources, and developing collaboration across organizations and geographical regions. Work such as this could contribute to a structured yet shared approach to the improvement of QS. Furthermore, a physician quality network/consortiumCitation47 should be considered by boards and provincial governments. This type of initiative would support physician leadership in QS by identifying effective improvement strategies and sharing of common challenges, tools, resources, and quality improvement initiatives. We believe there is merit in the continued support and development of such initiatives.

Limitations

We acknowledge that this study was conducted in 2010, which limits the impact and relevance of study findings for leaders and policymakers. Nonetheless, our current work within Alberta’s health system suggests that many of the factors identified in this study remain pertinent today. Several other limitations must be noted in interpreting our descriptive study findings. First, the small, heterogeneous survey sample size limits transferability of results to other Canadian QS teams in hospitals. However, the response rate for CEOs was modest and similar to other online surveys in our population, and respondents and nonrespondents did not differ across several characteristics. The qualitative data from a large number of interviewees suggested divergent experiences with QS; some were just starting their quality journey, while others were further along. Second, the qualitative data analysis and interpretation is subject to researcher bias. However, a rigorous process to ensure credibility of the data was undertaken by the research team. Third, participants from two provinces were not included in the study, one due to refusal and the other due to feasibility of language translation. Finally, each respondent was treated as a separate data point, and we did not account for intra-organization variability.

Conclusion

This article describes contextual factors that act as facilitators and barriers to the work of Canadian QS teams. Further research that seeks to delineate the relationships among factors and QS team effectiveness will permit a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanism by which these contextual factors influence the success or lack of success of QS teams. Key recommendations for organizations include the following: (1) creating a strategic improvement culture that is visible within the local and organization’s structure and processes (ie, QS ambassadors; quality circles and celebrations) and empowers QS teams and microsystems; (2) establishing organizational and regulatory structures and processes supporting physicians as co-executive sponsors or co-leads of QS teams; (3) prioritizing and mapping QS team initiatives to the organization’s strategic directions, accountability framework, and business plan; (4) developing strong committed leaders and clinical champions who can access data and other resources, create a sense of urgency, and demonstrate changes from QS team initiatives; (5) attending to the potential impact of organization size and geographic spread across provinces on the work of QS teams; and (6) monitoring the fidelity of the multiple methods used by quality improvement teams to implement their improvement projects.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge grant funding for the work from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PHE 85201) and Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions (200701285), and in-kind/and or cash contributions from Alberta Health Services, Canadian Patient Safety Institute, Faculty of Nursing (University of Calgary), Saskatoon Health Region, and Winnipeg Regional Health Authority. They would also like to acknowledge Karolina Zjadewicz and Halima Mohammed for assistance with the data analysis, and Drs. Sharon Straus and Jayna Holroyd-Leduc for their careful review of the manuscript. Results expressed in this report are those of the investigators and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of Winnipeg Regional Health, Saskatoon Health Region, Alberta Health Services, or Canadian Patient Safety Institute.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PowellAERushmerRKDaviesHTOA Systematic Narrative Review of Quality Improvement Models in Health CareEdinburghNHS Quality Improvement Scotland2009

- DenisJLDaviesHTOFerlieEFitzgeraldLMcManusAAssessing Initiatives to Transform Healthcare Systems: Lessons for the Canadian Healthcare SystemOttawa, ONCanadian Health Services Research Foundation2011

- Institute of MedicineTo Err is Human Building a Safer Health SystemWashington, DCNational Academy Press2000

- Institute of MedicineCrossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st CenturyWashington, DCNational Academy of Sciences2001

- DeversKJPhamHHLiuGWhat is driving hospitals’ patient-safety efforts?Health Aff (Millwood)2004232103115

- Lemieux-CharlesLMcGuireWLWhat do we know about health care team effectiveness? A review of the literatureMed Care Res Rev200663326330016651394

- WhiteDEStrausSEStelfoxHTWhat is the value and impact of quality and safety teams? A scoping reviewImplement Sci201169721861911

- AkinsRBA process-centered tool for evaluating patient safety performance and guiding strategic improvementHenriksenKBattlesJBMarksESLewinDIAdvances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation (Volume 4: Programs, Tools, and Products)Rockville, MDAgency for Healthcare Research and Quality2005109125

- KetringSPWhiteJPDeveloping a systemwide approach to patient safety: the first yearJt Comm J Qual Improv200228628729512066620

- StratingMMNieboerAPExplaining variation in perceived team effectiveness: results from eleven quality improvement collaborativesJ Clin Nurs20132211–121692170622612406

- SantanaCCurryLANembhardIMBergDNBradleyEHBehaviors of successful interdisciplinary hospital quality improvement teamsJ Hosp Med20116950150622042750

- OandasanIBakerGRBarkerKTeamwork in Healthcare: Promoting Effective Teamwork in Healthcare in Canada. Policy Synthesis and RecommendationsOttawa, ONCanadian Health Services Research Foundation2006

- SalasERosenMABuilding high reliability teams: progress and some reflections on teamwork trainingBMJ Qual Saf2013225369373

- MillsPDWeeksWBCharacteristics of successful quality improvement teams: lessons from five collaborative projects in the VHAJt Comm J Qual Saf200430315216215032072

- LynnJSchallMWMilneCNolanKMKabcenellAQuality improvements in end of life care: insights from two collaborativesJt Comm J Qual Improv200026525426718350770

- SchoutenLMHulscherMEAkkermansRvan EverdingenJJGrolRPHuijsmanRFactors that influence the stroke care team’s effectiveness in reducing the length of hospital stayStroke20083992515252118617664

- Matthaeus-KraemerCTThomas-RueddelDOSchwarzkopfDBarriers and supportive conditions to improve quality of care for critically ill patients: a team approach to quality improvementJ Crit Care201530468569125891644

- ShawEKOhman-StricklandPAPiaseckiAEffects of facilitated team meetings and learning collaboratives on colorectal cancer screening rates in primary care practices: a cluster randomized trialAnn Fam Med2013113220228S1S823690321

- WestMAHirstGRichterAShiptonHTwelve steps to heaven: successfully managing change through developing innovative teamsEur J Work Organ Psychol2004132269299

- CreswellJWPlano ClarkVLGutmannMLHansonWEAdvanced mixed methods research designsTashakkoriATeddlieCHandbook of Mixed Methods in the Behavioral and Social SciencesThousand Oaks, CASage2003209240

- LeechNLOnwuegbuzieAJGuidelines for conducting and reporting mixed research in the field of counseling and beyondJ Couns Dev2010886169

- BazeleyPIssues in mixing qualitative and quantitative approaches to researchBuberRGadnerJRichardsLApplying Qualitative Methods to Marketing Management ResearchPalgrave: Macmillan200414156

- Canadian Healthcare AssociationGuide to Canadian Healthcare Facilities (2007–2008)15Ottawa, ONCanadian Healthcare Association Press2007

- Canadian Institute for Health InformationCanadian MIS database: hospital beds staffed and in operation, fiscal year 2007–2008 Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2012/icis-cihi/H115-17-1-2009-eng.pdfAccessed October 10, 2009

- DillmanDASmythJDChristianLMInternet, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design MethodHoboken, NJJohn Wiley & Sons2008

- Accreditation CanadaCanadian Health Accreditation Report: Required Organizational Practices: Emerging Risks, Focused ImprovementsOttawa, ONAccreditation Canada2012

- LincolnYGubaENaturalistic InquiryBeverly Hills, CASage1985

- MilesMBHubermanAMQualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook2nd edThousand Oaks, CASage1994

- BraunVClarkeVUsing thematic analysis in psychologyQual Res Psychol20063277101

- BoeijeHA purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviewsQual Quantity2002364391409

- KaplanHCProvostLPFroehleCMMargolisPAThe Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ): building a theory of context in healthcare quality improvementBMJ Qual Saf20122111320

- Price Waterhouse CoopersNational Health Leadership Survey on Performance and Quality ImprovementOttawa, ONCanadian Health Services Research Foundation2011

- MassoudMRNielsenGANolanKSchallMWSevinCA Framework for Spread: From Local Improvements to System-Wide ChangeCambridge, MAInstitute for Healthcare Improvement2006

- BakerGRDenisJLPomeyMPMacIntosh-MurrayAEffective Governance for Quality and Patient Safety in Canadian Healthcare OrganizationsOttawa, ONCanadian Health Services Research Foundation, Canadian Patient Safety Institute2010

- CurtisJRCookDJWallRJIntensive care unit quality improvement: a “how-to” guide for the interdisciplinary teamCrit Care Med200634121128816374176

- FerlieEShortellSMImproving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: a framework for changeMilbank Q200179228131511439467

- BakerGRMacIntosh-MurrayAPorcellatoCDionneLStelmacovichKBornKDelivering Quality by Design: An Examination of Leadership Strategies, Organizational Processes and Investments Made to Create and Sustain Improvement in HealthcareToronto, ONLongwoods2008

- MacIntosh-MurrayAChooCWInformation behavior in the context of improving patient safetyJ Am Soc Inf Sci Technol2005561213321345

- StratingMMHNieboerAPZuiderent-JerakTBalRACreating effective quality-improvement collaboratives: a multiple case studyBMJ Qual Saf2011204344350

- BakerDPDayRSalasETeamwork as an essential component of high-reliability organizationsHealth Serv Res2006414 Pt 21576159816898980

- MohrJJAbelsonHTBarachPCreating effective leadership for improving patient safetyQual Manag Health Care2002111697812455344

- SullivanTDenisJLBuilding Better Health Care Leadership for Canada: Implementing EvidenceMontreal, QCMcGill-Queens University Press2011

- WhiteDEJacksonKNorrisJMLeadership, a central ingredient for a successful quality agenda: a qualitative study of Canadian leaders’ perspectivesHealthc Q2013161626724863310

- TaylorEGenevroJPeikesDGeonnottiKWangWMeyersDBuilding Quality Improvement Capacity in Primary Care: Supports and ResourcesRockville, MDAgency for Healthcare Research and Quality2013

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term CareAbout the Excellent Care for All Act Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ecfa/legislation/act.aspxAccessed May 21, 2014

- BirkenSALeeSYDWeinerBJUncovering middle managers’ role in healthcare innovation implementationImplement Sci201272822472001

- HayesCYousefiVWallingtonTGinzburgACase study of physician leaders in quality and patient safety, and the development of a physician leadership networkHealthc Q2010136873

- ReinertsenJLGosfieldAGRuppWWhittingtonJWEngaging Physicians in a Shared Quality AgendaCambridge, MAInstitute for Healthcare Improvement2007

- ReinertsenJLBisognanoMPughMDSeven Leadership Leverage Points for Organization-Level Improvement in Health CareCambridge, MAInstitute for Healthcare Improvement2005

- PatelNBrennanPJMetlayJBelliniLShannonRPMyersJSBuilding the pipeline: the creation of a residency training pathway for future physician leaders in health care qualityAcad Med201590218519025354070

- GuptaRAroraVMMerging the health system and education silos to better educate future physiciansJAMA2015314222349235026647251

- PronovostPJMillerMRWachterRMMeyerGSPerspective: physician leadership in qualityAcad Med200984121651165619940567

- HeathCHeathDSwitch: How to Change Things When Change Is HardNew York, NYCrown Business2010

- VersteegMHLaurantMGFranxGCJacobsAJWensingMJFactors associated with the impact of quality improvement collaboratives in mental healthcare: an exploratory studyImplement Sci201271

- CarterPOzieranskiPMcNicolSPowerMDixon-WoodsMHow collaborative are quality improvement collaboratives: a qualitative study in stroke careImplement Sci2014913224612637

- PannickSSevdalisNAthanasiouTBeyond clinical engagement: a pragmatic model for quality improvement interventions, aligning clinical and managerial prioritiesBMJ Qual Saf2016259716725

- MathieuJMaynardMTRappTGilsonLTeam effectiveness 1997-2007: a review of recent advancements and glimpse into the futureJ Manag2008343410476

- MarksMAMathieuJEZaccaroSJA temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processesAcad Manage Rev200126335676

- KotechaJBrownJBHanHInfluence of a quality improvement learning collaborative program on team functioning in primary health-careFam Syst Health201533322223025799255