Abstract

Purpose

Little is known about the long-term efficacy of virtual leadership training for physicians. This study compares two highly similar groups of Obstetricians-Gynecologists’ (OB-GYN) 6-month post-program changes in competency and skills after experiencing equity-centered leadership training in a virtual or in-person format.

Participants and Methods

Using a retrospective pre- and post-test method, we collected 6-month post-program data on 14 competencies for knowledge gains and skills use, comparing the virtual cohort (2021, n = 22) to the in-person cohort (2022, n = 33) in 55 total participants. Qualitative data from open-ended feedback questions informed on skills relevancy and professional impact since program participation.

Results

Data indicate strong, statistically significant knowledge and skills retention in both cohorts, with 63% of the virtual and 85% of the in-person participants responding. Data indicate participants report the course having a positive impact on their healthcare provision and nearly all report they made changes to their communication and leadership approaches in the 6-months after the program. 59% of the virtual and 55% of the in-person cohorts report new leadership opportunities since their participation and that the course helped prepare them for those roles. Qualitative data support the need for the training, specific elements of the training these physicians found particularly helpful, and that the learning was “sticky”, in that it stayed with them in the months post-program. There was a clear stated preference for in-person experiences.

Conclusion

Either virtual or in-person leadership training can result in long-term (6-month) significant retention and application of knowledge and skills in physicians. While limited in size, this study suggests that in-person experiences seem to foster more effective bonds and also greater willingness to participate in post-program follow-up. Physicians find equity-centered leadership training to impact their subsequent communication and leadership practices and they report career benefits even in 6-month follow-up.

Plain Language Summary

While physicians serve in many leadership roles in healthcare, leadership training is generally not part of their medical training. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Robert C. Cefalo Leadership Institute has provided an annual leadership training for obstetrician and gynecologist leaders since 2006. Our previous research has repeatedly shown the program is effective, with participants experiencing significant and impressive gains in leadership learning and skills development. The COVID-19 pandemic led to the 2021 program being held virtually with a return to an in-person format possible with the 2022 program. As such, the opportunity arose to compare the 6-month post-program learning and impact of these two formats, virtual versus in-person training, in two highly similar groups experiencing nearly identical program content. Both virtual and in-person participants rated their six-month post-program skill level/ability and skills use/implementation as significantly higher than pre-program and both groups noted the learning helped them be better physicians, communicators, and leaders. Additionally, many experienced new leadership opportunities in the 6-months post-program and most of those agreed that the program prepared them to take on those new roles. This study shows that our approach to physician leadership development is highly effective and that the learning demonstrated “stickiness” in that it persisted over time. While both virtual and in-person programs were highly effective, overwhelmingly the participants prefer in-person training to virtual training.

Introduction

While Physicians commonly function as leaders in healthcare, leadership training itself is not a standard component of medical training.Citation1–4 For physicians, leadership training is an additional skill they need to seek out and is thus more likely to take place in a post-graduate, mid-to-senior-career setting.Citation2,Citation4–6 A wealth of research and reviews attest to the crucial role leadership training plays as an important post-graduate development experience for physicians interested in improving how their teams function, enhancing outcomes of their clinical services, and/or extending their influence on policy issues.Citation1–8 Thus, leadership development initiatives for physicians typically focus on such topics as self-awareness, communication, diversity consciousness, change management, motivation, and improved participatory decision-making.Citation1–5,Citation9–11 Other topics shown to be useful to physician and other clinical leaders include negotiation, innovation, resilience, managing difficult conversations, crisis communications, emotional intelligence and tools for creating psychological safety.Citation2–4,Citation8,Citation9,Citation12–17 Additionally, some organization-based trainings highlight financial management as an institution-specific concern.Citation2,Citation4 Indeed, in Angood and Falcone’s white paper on Preparing Physician Leaders for the Future, they state, “formal leadership development is essential for physicians who are, or who aspire to be, leaders in their organizations”Citation2 while van Diggele et al note that

as a learned skill, the topic of leadership is gathering momentum as a key curriculum area…. Leadership consists of a learnable set of practices and skills that can be developed by reading literature and attending leadership courses.Citation3

Yet gaps persist in the literature about program efficacy, longer-term impact, and adaptability to alternative formats as well as a depth of understanding of the wide variety of leadership skills important across a physician’s career.Citation1,Citation2,Citation4

Given the constraints of physician time, resources and the implications of events like the COVID-19 pandemic, understanding how to meet the leadership development needs of physicians despite the inability to convene in-person experiences also rises in importance. However, relatively little is known about the efficacy of virtual leadership training in healthcare professions, and more specifically for physicians, and in particular with respect to women’s healthcare doctors. In our exploration of the literature, we found no other papers examining the long-term impact and efficacy of virtual versus in-person leadership training for women’s health physicians beyond our own work.Citation11

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Robert C. Cefalo Leadership Institute has been training women’s health physician leaders since 2006, with nearly 700 alumni from the program to date. We have previously reported on our work, showing clear impact on in-person learning and reported career growth opportunities in both the immediate short-term and longer term (6-month) follow-up on many of the key physician leadership competencies noted in the literature above.Citation8 Data reported here support the efficacy and effectiveness of the ACOG-Cefalo program approachCitation8 at the 6-month post-program timepoint, suggesting that the learning was “sticky”, with skills and tools imparted remaining effective and relevant to the physician leaders months after completing the program. In 2019, a systematic review of physician leadership programs by Geerts et alCitation6 identified the Cefalo program as one with strong learning outcomes as compared to other similar programs reported in the literature.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused workforce development and continuing education programs to pause and subsequently reformat to virtual delivery. Leadership development programs were no exception to that experience.Citation11,Citation12 The 2020 Cefalo program paused, given that it was to be held just weeks into the national stay-at-home recommendations. While we had some experience with similar virtual adaptation through our work with the Clinical Scholars leadership development program (focused on small interprofessional teams working to close the gaps in health disparities in their local communities,Citation14), we had not previously faced the need to adapt our training for our work with ACOG Cefalo program, which focused solely on OB-GYNs. We recently reported on the success of virtual adaptation of our leadership training, by comparing the short-term immediate program outcomes on knowledge and skills development with practicing OB-GYN’s engaging in the program either virtually or in-person.Citation11 Subsequently, we were able to study the long-term (6-month) impact on learning in this same group and explore the career impacts of that training, which we report here, comparing the 2021 Cefalo program, which was held virtually, to the 2022 program, which returned to an in-person format.

The demands of the pandemic were particularly notable for healthcare providers and brought into focus the need to address and nurture psychological safety on the teamCitation17 as well as physician resilience.Citation18–20 The effects of the pandemic also highlighted the need to support physician leaders with sophisticated communications skillsCitation21 during “VUCA” (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, Ambiguous) crises.Citation22 The pandemic heightened the focus on physician leaders to address equity concerns magnified by the crisisCitation9,Citation23,Citation24 and subsequent policy actions that impact the practice of obstetrics and gynecology.Citation25 Given the rapidly evolving context in which physicians work and the immense and multifaceted burdens they shoulder,Citation2 leadership training focused on healthcare providers needs to support the development of a sophisticated and broad array of practical skills. In multiple ways these contextual changes serve to reinforce the call for building physician leadership capacity that was so clearly sounded early in the millennium.Citation26 In addition, given the investment required to deliver such sophisticated development experiences, it is crucial to understand how leadership training is impactful and meaningful.

While some authors understandably highlight the lack of published efficacy results for leadership training,Citation1,Citation5,Citation10 the ACOG-Cefalo program has previously published impressive immediate training outcomes in a sophisticated and diverse-set of leadership skillsCitation11 as well as 6-month follow-up of competency-based learning outcomes from in-person programs that show enduring statistically significant gains in core competencies coupled with expanded leadership opportunities, for which the vast majority of participants indicated the skills they learned in the program prepared them to be successful in these new roles.Citation8 Yet given that we had never previously delivered the Cefalo training virtually, we became curious about the impact on both short-term and long-term learning when the program needed to modify to meet the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to pivoting our content to suit virtual engagement, it became clear that the Cefalo experience would need to directly address issues around physician burnout and resiliency,Citation19,Citation20 as well as equity, diversity, and inclusion concernsCitation2,Citation9,Citation15 in particular, which made a virtually delivered program more ambitious and complex. The 2021 virtual program was centered on 14 overarching leadership competencies (), with an additional emphasis on resilience and wellness. These competencies align well with the typical focus areas for physician leadership development noted above and were initially based on validated competencies for the Food Systems Leadership Institute, an academic leadership program sponsored by the Association of Public and Land Grant Universities throughout the US and CanadaCitation8,Citation27 and a US-based leadership program to train the maternal and child health public health workforce.Citation28 These competencies were recently re-evaluated and validated with interprofessional healthcare teams through the Clinical Scholars program.Citation13,Citation29 With a return to an in-person format in 2022, we maintained those curricular changes and wanted to investigate how the delivery format might have impacted longer-term (6-month) retention of participant skills and self-efficacy, given the inherent differences between a virtual and an in-person experience and our findings of no previous research reported in the literature providing such a long-term comparison.

Table 1 14 Plain Language Leadership Competencies of the ACOG-Cefalo Program

The objective of this analysis was to compare 6-month competency-based learning retention outcomes for the ACOG-Cefalo Leadership Institute 2021 (virtual) and 2022 (in-person) cohorts as relates to both physicians’ leadership skill development and leadership self-efficacy.

Methods

Program Description

The ACOG-Cefalo program in 2021 was hosted virtually over a four-day period, convening between 11:00AM through 6:00PM, Eastern Standard Time (EST). The program was hosted using the ZoomCitation30 platform and supported by the WhovaCitation31 Meeting App. The Whova App stored recordings of virtual sessions. The ACOG-Cefalo program in 2022 was hosted in-person over 3.5 days from 8:00 AM through 6:00 PM EST. provides a comparison of the two programs. The Zoom platform was not used. Consistent with the 2021 program, the Whova Meeting App was offered as a general meeting facilitation tool which allowed both cohorts to have access to identical opportunities for participants to meet and connect in electronic, self-directed ways, both during and post-program. Of note, sessions were not recorded in 2022 during the in-person session. In both the virtual 2021 program and the onsite 2022 program, the App was used only nominally by participants, and thus was not a focus of this study.

Table 2 Comparison of 2021 and 2022 ACOG Robert C. Cefalo National Leadership Institutes

Most of the synchronous curriculum topics were provided by the same speakers both years, regardless of whether the curriculum was virtual or in-person. A comparison between the session formats, including sessions offered, training hours provided, and number of attendees was performed and the immediate post-program learning outcomes between these delivery formats has been previously published.Citation11

In the six months following the intensive, synchronous program for both cohorts, four follow-on webinars addressed the topics of Imposter Syndrome, Sources of Power in Negotiation, Creating Effective Accountability Structures, and Making Cultural Change Real, with speakers and the formats for the follow-on webinars being identical in both years. Additionally, each Fellow was provided with unlimited and self-directed access to an online library of short (~30-minute) modules addressing leadership skills on a wide variety of topics, utilizing FastTrack LeadershipCitation32 online at WeTrainLeaders.com. The FastTrack Leadership Library topics are closely aligned with the program curricula and previous research has found them to be useful, relevant, practical, and enjoyable by participants.Citation28 An identical selection of leadership books and other written materials were included in the program materials for both years. Fellows were encouraged to use those resources post-program.

Participants and Data Collection

Study participants are OB-GYNs enrolled in the ACOG-Cefalo Leadership Program and represent a purposive sample made up of the 2021 cohort (32 attending virtually with 22 completing 6-month post-program survey) and the 2022 cohort (39 attending in-person with 33 completing 6-month post-program survey) (). Program Fellows are nominated to participate based on their elected leadership roles and service to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, a multinational entity representing 62,000 practicing OB-GYNs. All participants in each cohort were asked to electronically provide feedback through a survey in QualtricsXMCitation33 approximately six months after completion of the leadership institute. Invitations to complete the voluntary six-month survey were sent by Email to all participants with periodic reminder emails and an incentive of a YETI mug for participants who completed the survey. The 2021 follow-up survey was open from March 1, 2022, through June 10, 2022, while the 2022 follow-up survey was open from November 1, 2022, through December 14, 2022. Institutional Review Board protocols and ethical procedures at the University of North Carolina were followed (IRB protocol #18-2037). Informed consent was given on the electronic evaluation document prior to completing the evaluation form. Demographics were collected through self-reported survey questions.

Table 3 Demographics of ACOG Robert C. Cefalo National Leadership Institute Participants Who Completed a 6-Month Follow-Up Survey in 2021 or 2022

Participants were asked to rate their skill level (as a measure of ability) and skill use (as a measure of implementation) of the competency for each of 14 leadership competencies using the retrospective pre-and post-test method.Citation34–38 Plain language definitions of the competencies were provided on the evaluation form. For skill level “six months ago” (before the training) and “now”, ratings were collected with a 5-point Likert scale,Citation36 where 1 = unskilled, 2 = low skills, 3 = moderate skills, 4 = good skills, and 5 = excellent skills. Similarly, for skill use (implementation) before the training and present day, participants rated their use of each competency on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = not at all, 2 = to a small degree, 3 = moderately, 4 = to a large extent, and 5 = extensively. Other survey questions included “How have the skills you acquired from the course impacted the healthcare you provide to your patients?” with responses given on a 5-point rating scale (1 = Negative impact, 2 = No impact; 3 = Little impact, 4 = Moderate impact, 5 = Strong impact); and “Have you made any changes in your communication and leadership approaches as a result of participating in this course?” with responses given on a 5-point rating scale (1 = No impact, 2 = I do not know; 3 = Yes, one or two, 4 = Yes, some, 5 = Yes, many). Participants were also asked whether they would recommend the course to their colleagues and whether they had received a promotion, had a change of job or taken on new leadership opportunities since the course (responses Yes/No); and: “and if so, to what extent did the course prepare you for the new leadership opportunities?”, (with ratings of 1 = Not at all; 2 = A little; 3 = Somewhat; 4 = Very much).

Additional qualitative feedback was collected: 1) Were there any skills or lessons you learned at the ACOG Leadership Institute that have proven to be particularly “sticky”? [“sticky” in that they stuck with you, strongly resonated with you, or moved you?] If so, please describe; 2) Reflecting on your response to the previous question, do you feel like the lessons you listed resonated even more so in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic? If so, why do you think that?; 3) What do you feel was the most valuable lesson or skill learned from the ACOG Leadership Institute?; and 4) Were there any skills you felt you did not learn enough about, or content that was not included in the training that you wish had been? If so, please let us know in the space below. Please feel free to provide any additional comments or suggestions for the program staff to consider.

Data Analysis

Quantitative Data

The survey data was exported from QualtricsXMCitation33 to a secure Microsoft Excel program for descriptive analyses, including counts and percentages of demographic data and means and standard deviations of skill level and skill use scores for each leadership competency. Mean differences between scores six months ago/before the program and scores now for skill level and skill use of each leadership competency were calculated in Microsoft Excel. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank testingCitation39,Citation40 was conducted in StataSE16Citation41 software to assess the statistical significance of the mean differences. This non-parametric testing approach was usedCitation11 due to small sample sizes. Participants with missing responses to survey questions were excluded from analysis on a test-by-test basis.

Qualitative Data

The qualitative feedback from each cohort was analyzed by three graduate-level research assistants to highlight emergent themes. All feedback statements were coded independently to determine the frequency based on the respective year. Individual feedback submissions by participants sometimes covered multiple topics, so multiple qualitative codes may apply to each individual feedback response. It must be noted that survey data were evaluated without any personal identifiers, and thus it is possible that a participant could have left similar feedback to more than one open-ended question.

Results

Descriptive Results

provides a comparison between the session formats, including sessions offered, training hours provided, and number of attendees.

While the program is designed to accommodate up to 40 participants, the 2021 virtual program enrolled 32 participants, and the 2022 in-person program enrolled 39 participants. The 2021 follow-up survey was completed by 22 of 32 (69%) virtual institute participants and the 2022 follow-up survey was completed by 33 of 39 (85%) in-person institute participants. Fellows in both cohorts who participated in the 6-month follow-up study in 2021 and 2022 were highly similar with respect to age and areas of practice, but the virtual 2021 group skewed more female and more diverse ().

Quantitative Results

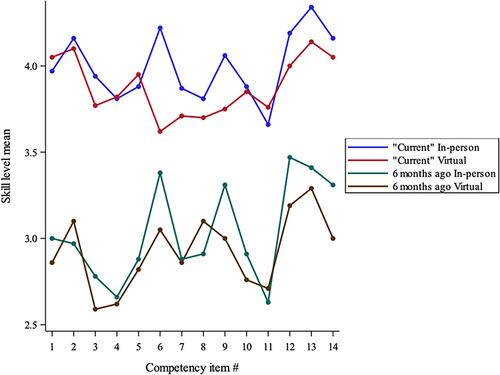

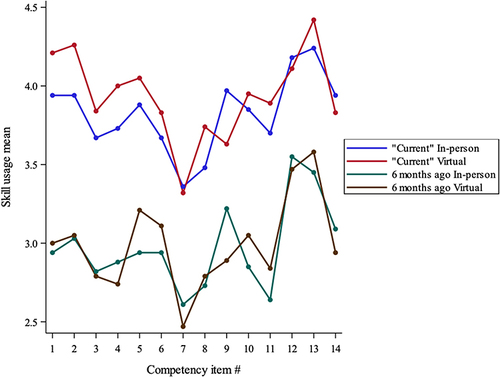

Regardless of whether Fellows attended the program virtually or in-person, they rated their 6-months post-program skill level (ability) and skills use (implementation) on each of the 14 competencies as improved to a degree that met statistical significance at either the p < 0.01 or the p < 0.001 level, indicating strong differences in the scores (). Fellows participating virtually rated the 6-month “stickiness” of their skill ability as greater on nine of the competencies as compared to their in-person colleagues. One competency (Women’s Health Policy and High-Level Leadership) was rated with the same degree of improvement (0.75) in both groups for ability. For the change in skill usage (implementation), the virtually attending group rated their shift in scores as higher on eight of the competencies, as compared to their in-person attending counterparts. In-person attendees rated their skills usage as improving to a greater degree on six of the competencies, however three of those were only a 0.1 difference in scores and thus truly non-remarkable.

Table 4 Skill Level (L) and Usage (U) After 6 Months Across Virtual (2021, n = 22, 66.7%) and in-Person (2022, n = 33, 84.6%) ACOG Robert C. Cefalo National Leadership Institutes

For the 2021 virtually attending group, the pre-program (“six months ago”) scores for skill level (ability) ranged from a low of 2.59 ± 0.85 (“Selling a Change Message”) to a high of 3.29±0.78 (“Diversity and Inclusion”) and for pre-program skills use (implementation) scores ranged from a low of 2.47±1.02 (“Managing Media Communications”) to a high of 3.58±1.02 (“Diversity and Inclusion”). For the same virtual group, the post-program (“now”) scores for skill level (ability) ranged from a low of 3.62±0.86 (“Applying Advocacy Skills”) to a high of 4.19±0.59 (“Practice of Multiculturalism”) and for post-program skills use (implementation) scores ranged from a low of 3.32±1.29 (“Managing Media Communications”) to a high of 4.42±0.69 (“Diversity and Inclusion”) ( and ).

Figure 1 Comparison of skill level means among virtual and in-person groups in competency items #1-14.

Figure 2 Comparison of skill use means levels among virtual and in-person groups in competency items #1-14.

For the 2022 in-person attending group, the pre-program (“six months ago”) scores for skill level (ability) ranged from a low of 2.63±0.83 (“Negotiation Skills”) to a high of 3.47±0.92 (“Practice of Multiculturalism”) and for pre-program skills use (implementation) scores ranged from a low of 2.61±1.27 (“Managing Media Communications”) to a high of 3.55±0.87 (“Practice of Multiculturalism”). Their post-program (“now”) scores for skill level (ability) ranged from a low of 3.66±0.70 (“Negotiation Skills”) to a high of 4.34±0.65 (“Diversity and Inclusion”) and for post-program skills use (implementation) scores ranged from a low of 3.36±1.45 (“Managing Media Communications”) to a high of 4.24±0.83 (“Diversity and Inclusion”) ( and ).

Greater variance exists in the retrospective pre-training scores for competencies between the virtual and in-person groups. In the post training (“now”) scores, the only delta between the virtual and in-person cohorts that exceeds 0.5 is for the Applying Advocacy Skills Using a Science-Based Approach, where the 2022 in-person group’s ratings were 0.58 greater than the virtual cohort’s 6-month post-program rating.

In terms of the impact of the leadership course on the healthcare these physicians provide to their patients, 16 (73% of respondents) of the 2021 virtual cohort participants responded “moderate impact” and 5 (23%) responded with “strong impact” while in the 2022 in-person cohort 6 (18%) responded with “strong impact”, 18 (55%) with “moderate impact”, and 6 (18%) reported little impact and 2 (6%) reported no impact (not all participants responded to the question). All 100% of the virtual cohort and 97% of the in-person cohort answered that they had made changes in their communication and leadership approaches with the vast majority answering “yes, many” or “yes, some”. In response to the question: “Since the completion of the course, have you received a promotion, had a change of job, or taken on new leadership opportunities?”, 62% of virtual cohort participants and 55% of in-person cohort participants responded affirmatively with all of those respondents agreeing that the course helped prepare them for those roles, with the vast majority answering “very much” ().

Table 5 Survey of Reported Impact of Course Participation on 6-Mo Behaviors and Leadership Opportunities: A Comparison Between Virtual and in-Person Program Formats

Qualitative Results: Four (4) Open-Ended Questions

Open-ended responses were manually counted and thematically analyzed for each question posed in the 6-month survey (). Eighty-two percent of comments from the virtual 2021 cohort expressed gratitude for the experience or noted positive comments. A representative quote states:

I want to thank all the individuals who have invested countless hours to create such a well-developed program. It astonishes me how much I still have to learn about myself and others. All those involved deserve awards for the energy and tenacity that they bring!

There were no open-ended comments that expressed negativity about the virtual experience, however many stated their strong desire for the course to be held in-person. For the in-person cohort in 2022, 36% of all the comments shared were positive or expressing gratitude and no comments provided constructive criticism. A representative quote states:

Thank you for all that you do. I appreciate the time and topics discussed. I enjoy the [post-program follow–on] zoom lectures when I am available to make it. This conference poured a lot into me and I am grateful for that.

Comments shared about both the 2021 virtual experience and the 2022 in-person experience were similar in that there were no negative comments shared about either leadership training experience.

For open-ended question 1, participants were asked:

Were there any skills or lessons you learned at the ACOG Leadership Institute that have proven to be particularly ‘sticky’? [‘sticky’ in that they stuck with you, strongly resonated with you, or moved you?] If so, please describe.

A prominent theme emerging from the 2021 virtual cohort’s responses indicated that they found the negotiation and inclusivity competencies were sticky as the sessions required individuals to have difficult conversations with one another. Participants noted appreciation for being able to step out of their comfort zone and discuss topics that could benefit the greater good (ex: health equity and being able to recognize one’s value). A representative quote from a participant states:

Negotiation and advocacy skills were the most foreign/unfamiliar to me - but were highly desirable skills. These sessions in particular, really grabbed my attention and provided me a knowledge and skills acquisition platform to grow from.

A prominent theme emerging from the 2022 in-person cohort’s responses was that communication was a “sticky” topic, given the fact that physicians often have to navigate working with different personalities amongst their teams and their patients. The ability to deliver good or bad news, while considering the personality of the individual being spoken with, is a skill for which participants described they desired more experience. In addition, a second theme emerged that the “upstander” and “bystander” concepts were experienced as “sticky”.

For open-ended question #2, participants were also asked:

Reflecting on your response to the previous question, do you feel like the lessons you listed resonated even more so in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic? If so, why do you think that?

A prominent theme emerging from the 2021 virtual cohort’s responses indicated that participants found that the COVID-19 pandemic opened a new door for physician leadership, as leading an interdisciplinary team was critically important at the time. They noted that “old ways of leadership” were not applicable during the pandemic, which required successful physicians to make changes to the way they practice. Participants noted that collaborative efforts needed to occur so that care was still streamlined given the pandemic. A prominent theme emerging from the 2022 in-person cohort’s responses indicated that the skills learned resonated as they went from in-person to telehealth throughout the pandemic and then had to re-learn how to facilitate in-person interactions with their team. An additional theme emerged regarding participants’ heightened awareness of others’ views and looking out for areas where marginalization can be avoided in team dynamics.

For open-ended question #3, participants were asked, “What do you feel was the most valuable lesson or skill learned from the ACOG Leadership Institute?” The themes emerging from the 2021 virtual cohort indicated that the opportunity to complete the personal assessments was an “eye-opener” for many individuals, as they were able to reflect on their current styles and on what they could identify to improve. Another theme was participants’ identification of their ability to “hear” (register, understand, comprehend, and reflect that to the speaker) other physicians’ experiences as empowering, being attributed to helping the individual participants recognize they are not alone in their leadership journey. As one participant stated:

There is no one way to lead. We have to constantly evolve as leaders and change how the common message is presented based on the audience. It is important to really get to know your team and how they communicate and what motivates them.

In response to the same question, the themes emerging from the 2022 in-person cohort indicated that communication was a vital skill they learned, with notations as important because they encounter different personalities on a daily basis within their work. Many stated that improved communication contributes to their ongoing work of team building, leading to better patient outcomes. As a representative quote, one participant stated,

Leadership skills are impactful even on an individual level as a physician leader not only with the organizations I work with, but with the patients I care for individually each day.

Lastly, for open-ended question #4, participants were asked:

Were there any skills you felt you did not learn enough about, or content that wasn’t included in the training that you wish had been? If so, please let us know in the space below. Please feel free to provide any additional comments or suggestions for the program staff to consider.

The majority of participants in 2021 virtual cohort expressed that they wanted more time with the executive coach (80 minutes was provided), to better understand how they can improve their leadership qualities. An additional theme emerged noting the challenges of Zoom sessions rather than in-person learning, describing that being in-person would have been more conducive to their learning.

In response to the same question, themes that emerged from the 2022 in-person cohort included their appreciation and enjoyment at having the opportunity to attend the program, with notations that the in-person instruction was beneficial to their learning as they were able to digest the information, ask follow-up questions and receive real time answers, having the ability to foster wholesome discussions and allowing for networking opportunities.

With regard to post-program self-directed use of the supplemental learning materials (modules, books), roughly half of the participants affirmed that they made use of at least some of the reading or other supplemental materials given at the course for post-program self-guided study with about one-third of participants reporting use of two or more of the materials (generally the online modules and one or two of the leadership books).

Discussion

Certainly, it is important to know that workforce development programs are impactful in the short term, providing participants with frameworks and practical tools relevant to the day-to-day challenges they face. Other programs have shown that pivoting from in-person based training to virtual training does not sacrifice learning gains in the immediate sense.Citation14 This work echoes the recent work of Nilaad, et al,Citation42 who found no negative impacts on learning when a pharmacy curriculum was given as either live-virtual or in-person to medical and pharmacy students. Similarly, Reddy, et al,Citation43 examined the acceptability of virtual vs in-person grand rounds and found that each delivery format could be effective despite some personal preferences for one format over another. Similarly, we recently published that these same cohorts of physicians found the immediate learning experience of synchronous, intensive, equity-centered leadership training to be highly impactful to their knowledge acquisition and their self-efficacy, regardless of whether they participated in a virtual or an in-person cohort.Citation11

This study compares the 6-month follow-on evaluation of the “stickiness” of leadership skills learning and usage in two highly similar groups of physicians participating in a nearly identical, equity-centered leadership program, which was delivered either virtually (in 2021) or in-person (in 2022). Similar to our previous short-term focused work in evaluating this model of leadership training in interdisciplinary healthcare providersCitation12 and in groups of physician leaders,Citation8,Citation11 these new data indicate that, regardless of the format of program delivery, equity-centered leadership training can strongly impact knowledge of such leadership skills, as well as reported subsequent implementation of those leadership skills, over longer periods of time in OB-GYN physicians. Our data here comparing competency-based learning between the two delivery formats indicates that while positive shifts in learning are sustained at six-months post-program in both formats, there is very little notable difference (delta of ≥0.5) between the virtual or in-person instruction. The data here indicate statistically significant—and similar—shifts in each of the 14 competencies under study in this investigation for both virtual and in-person equity-centered leadership training.

Some variance between cohorts is seen with respect to retrospective pre-training ratings for both skill level (ability) and for skill use (implementation), while ratings for “current” (“now”) level of ability and implementation were far more similar, suggesting that the training itself helped to level out differences that existed amongst the groups, as would be expected.

Similar to our previous findings,Citation11,Citation14 Abarghouie, et al,Citation44 found that when 40 surgical technology students were randomly assigned to virtual or traditional (lecture-based, in-person) teaching formats, the short-term learning outcomes were nearly identical for both formats. However, in contrast to our findings here, their longer-term examination scores illustrated significant differences in content retention and recall performance, favoring virtual instruction.

In examining the impact on the scores for knowledge/learning and skills/usage gains in our two cohorts of physicians, the data show strong shifts. While positive shifts in immediate knowledge and skills gain would and should be expected in any professional development training provided by an experienced and qualified faculty, our team was particularly pleased to discover how strongly the participants felt their skill level had grown, even so many months after the training. The shifts in skills use at the follow-up timepoint were also strong and help support the theory that these trainees did indeed “move the needle” of their knowledge and ability through participating in the program. The strong shifts in skills usage is of particular import, since that indicates that the competencies of focus were directly relevant to the actual, practical needs of the learners back in their medical offices and healthcare systems. One of the goals we talk about in the Cefalo program is the curricular focus on “WISDOM: What I Shall Do On Monday”, meaning that we want the content to be directly practical rather than merely theoretical. We believe that the program’s skills-and-practice-focus, as opposed to a concept- or theory-focus, is a likely explanation for the long-term strong shifts in both skills level and skills use seen in this analysis of learning.

It was interesting that the scores are relatively similar for both virtual and in-person instruction and thus from these data we cannot imply that one method was more effective than the other. Regardless of whether the program was provided in-person or virtually, we have some hypotheses for why the six-month follow-up data showed such dramatic learning. First, this program has been provided by the same core team for nearly two decades—a team which has always deeply included the stakeholders served in both planning and implementation and which has consistently applied the leadership concepts taught to its own functioning. Two decades provides considerable time for honing teamwork, content, and delivery. The same core team has been involved in several other leadership development programs with similar demonstrated impact for academic leaders,Citation27,Citation45 interprofessional healthcare teams,Citation12–16 and public health workforce groups.Citation28 Prior to the 2021 virtual program reported on here, the team had experience with adapting multiple other nationally prominent leadership programs to the virtual environment, and those lessons learnedCitation14,Citation46 contributed to the extremely smooth transition of the Cefalo program to virtual in 2021 after the pause during the COVID year. Given the qualitative feedback from that virtual program, we were not surprised at the strength the immediate post-program learning reportedCitation11 nor by the shift in skill levels and usage levels of the program competencies reported here more than six months later for either group.

For the virtual group, the largest shift for both learning and skills use was for the competency Leading Change Successfully, with score shifts of 1.20 and 1.26 respectively, which indicate very strong shifts in both understanding and the confidence to implement the skills. The qualitative comments from this group acknowledged the need to adapt to changes imposed by the pandemic (eg the “old ways of leadership” were not applicable during the pandemic), thus triangulating the quantitative data. For the in-person cohort of 2022, the largest shift for knowledge gain (learning) was 1.19 for Leading Others and Empowering Their Success, which echoes the qualitative theme of having to “re-learn how to facilitate in-person interactions with their team” and avoiding marginalization in team dynamics. For the in-person cohort, the largest shift for skills use was 1.03 for Negotiation Skills, which are commonly considered an important topic in physician and other healthcare-oriented leadership development programs.Citation1–3,Citation8,Citation10–14 These scores are corroborated in the separate answers to the open-ended questions, in which 100% of the 2021 cohort and 97% of the 2022 cohort agreed that they “made changes in my communication or leadership approach” based on their learning in the program. Furthermore, more than half of participants noted that they had new leadership opportunities since their training (62% for the virtual cohort and 55% for the in-person cohort), for which 100% of the responding participants in both cohorts agreed that the course prepared them for those opportunities. All (100%) of the responding virtual cohort and 100% of the responding in-person cohort responded affirmatively to the question “this course was beneficial to my practice as a physician leader”.

Clearly both groups entered the program interested in and engaged with issues around equity, diversity, and inclusion,Citation2 as their pre-program scores for knowledge (learning) and skills (usage) were highest for the competencies of Diversity and Inclusion and the Practice of Multiculturalism. The shifts in knowledge and skills in these areas remained impressive, between 0.63 and 0.94 (and statistically significant at the p < 0.01 to the 0.001 levels), indicating that even these audiences, who were previously invested and engaged in the practice of multiculturalism and diversity and inclusion, found the materials enhanced their already rather advanced knowledge and ability. Indeed, their post-program 6-month scores were highest in the Diversity and Inclusion (virtual group: 6-month post skills, in-person group: 6-month post knowledge and skills) and for The Practice of Multiculturalism (virtual group: 6-month post knowledge) competencies. Our offices have been asked by external training groups and academicians

whether it could be appropriate for those who are more advanced in diversity, equity, and inclusion skills to be excused from such material as they enter a leadership development program?

We do not agree with this sentiment, as we view a) the understanding of self and others; b) the appreciation of the differences between people; and c) developing the skills to create a culture fostering belonging for everyone on the team, as a never-ending journey of enlightenment. The data from these highly equity-engaged participants entering the ACOG-Cefalo program in both cohorts visibly illustrates that significant learning and skills development continue to occur, even in those with broad previous exposure and passion for the content. Like leadership development in general, one should never stop growing one’s leadership skill set nor turn one’s back on opportunities to learn, engage, and grow. Leadership learning is intended to be a life-long endeavor, as it is a journey with no end.

Independent of delivery format, it is important to pursue understanding of the longer-term contribution of physician leadership development approaches to skills acquisition and use, particularly when it comes to the more nuanced skills involved in equity-centered leadership.Citation2 While there are several research publications providing evidence of efficacy,Citation2 such as the systemic reviews of leadership programs by Frich et alCitation5 in 2015 and later by GertsCitation6 et al, in 2020, there is relatively less understanding of the continuing impact on knowledge and skills many monthsCitation8 or even yearsCitation27–45 after the training. While the findings of Abarghouie, et al,Citation44 reported that virtually delivered instruction had a stronger impact on longer-term content retention and recall performance, our own findings showed very similar outcomes between the two modalities. Admittedly, career leadership development approaches differ greatly from technical course instruction, as do the methods of evaluating impact on learning and subsequent behaviors.

Our previous work in small interprofessional teams engaging in equity-centered leadership training demonstrated statistically significant changes in immediate learning gains as measured by topic, rather than by over-arching competency, regardless of whether the delivery method was virtual or in-person. Our “lessons learned” working with these physician audiences echo and confirm those found with the Clinical Scholars program,Citation12,Citation14 namely that virtual content delivery imposes time restraints (time zones, screen-time fatigue) and is far less efficient in terms of content delivery than traditional face-to-face formats, resulting in a slightly reduced content in order to fit the constraints. While the data reported here support the hypothesis that this virtual adaptation of the ACOG-Cefalo program was highly successful, translation of in-person programs to virtual ones can be challenging to program directors and faculty and require a great deal of careful thought and planning. In short, success is not guaranteed simply because the in-person format might have proved to be impactful and successful previously.

Given the value of physician time and the investment required for mounting a leadership development program, part of the “return on investment” consideration is the assurance that the endeavor offers “sticky” learning that will continue to benefit the participant long after the training has passed. This long-term impact is an important consideration regardless of whether that program is deployed virtually or in-person. These data support the efficacy of either delivery model, as demonstrated by the statistically significant differences in scores for both skills learning and skills implementation in the six months post-program, which gives us confidence that achieving this “stickiness of learning” is not only a realizable goal but should be an expected one. Other published research has found leadership learning to be “sticky” over time, both with previous cohorts of these physician leadersCitation8 and with academic leaders.Citation27–46 While those studies support the subsequent career impact on the participants, neither of those investigations compared the learning in virtual vs in-person contexts.

Interestingly, in this work we did notice a difference in willingness to participate in a virtual leadership development program both overall and across cohorts. Several participants who initially signed up for the 2021 program, with the hopes that it would be offered in-person, later deferred their participation to 2022 (data not shown). There was an overwhelming interest for the in-person format, which may partially account for the lower number of enrolled virtual participants in 2021. In the literature, the Clinical Scholars programCitation14 conducted a similar study, comparing similar leadership development programs implemented either virtually or in-person, however that program was much longer in duration (3 years) and provided project-based funding contingent upon participation. Not surprisingly, we did not observe similar hesitancy to participate virtually in the ongoing CS program as we found in our newly-enrolled physician participants in this single-meeting course.

Additionally, a greater percentage of females made up the virtual cohort of 2021, with 84% of attendees identifying as female, compared to 71% of the 2022 onsite program (data not shown). With respect to participation in this 6-month follow-up survey, 90% of those responding from the 2021 (virtual) program reported identifying as female, as compared to 70% of the 2022 onsite participants. There were no notable gender differences for the 2022 in-person cohort between those who attended or responded to the 6-month follow-up survey. It was also interesting to note that there was slightly greater participation of individuals from communities of color in the virtual session, with 48% of those participating in 2021 identifying as such, and 50% of the 2021 6-month follow-up respondents representing communities of color. For the 2022 in-person program, 38% of attending participants identified as representing various communities of color, as did 36% of the 6-month follow-up participants. This information is merely observational, and represents individuals voluntarily identifying as Asian, Black, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or Other. We did not collect data for the present study as to why individuals selected a virtual or an onsite experience and whether that choice relates to preference, opportunity, or other reasons. It is important to note that despite several emails requesting participation in the 6-month follow-up survey, only 69% of those virtually attending responded, while 85% of their in-person counterparts responded. Our data collection window was also longer for our virtual participants as compared to that for our in-person ones. Our data fail to provide insight into explanations for this difference in survey response.

As reported elsewhere,Citation11 we also observed a difference in the degree of post-program connections between the virtual program participants and those who were convened in-person. The 2022 group connected dozens of times weekly for several months after the event while the virtual group rarely used any of the same systems provided to them to connect through group Email and the Whova meeting app platform. Given that topics of conversation focused on policy issues in healthcare, we hypothesize that issues-of-the-day could have driven this connection. However, we cannot discount the potential influence of cohort differences or differences in how group identity was formed in the in-person context. The qualitative data in this study shed some light on the benefits of having an in-person training program. Individuals who attended the in-person retreat reported increased connection between themselves and their executive coach as well as feeling more “fulfilled” after attending. Those who attended the virtual group reported that an in-person format would be more conducive to their learning and would help the material resonate with individuals more.

There were curricular sacrifices made in the virtual deployment of the program as compared to its in-person counterpart, including shorter days (to accommodate a variety of time zones), more time devoted to ensuring that the virtual format was conducted smoothly, and greater time devoted to creating interpersonal connections in the virtual space—which resulted in a more streamlined and less expansive/more focused curriculum. In the 2022 in-person format, the time not devoted to facilitating the program flow was spent on participants networking informally with colleagues and developing meaningful relationships. Despite the curricular adaptations, the outcome scores for both skill level and skill use were strikingly similar. In fact, there was only one post-training score—for Applying Advocacy Skills Using a Science-Based Approach—that rose above the 0.5 threshold, in which the in-person attendees reported a delta for skill level that was 0.6 greater than the virtually-attending ones. One hypothesis for this striking difference is the emergence of legislative threats to women’s healthcare which were more prevalent during the in-person (2022) program year.Citation25

Practical Implications

Physicians are leaders of their teams and across their organizations, however conventional medical training does not typically encompass the skills for nurturing diversity and inclusion, as those healthcare leaders create motivated team cultures which support psychological safety. Physicians often need to lead change both persuasively and successfully while they negotiate and innovate to improve services and patient outcomes, particularly given the political intrusion into healthcare and ever-leaner insurance reimbursement realities. Skills for managing media communications can become important as physicians rise in the ranks of leadership, and without effective training can lead to devastating impacts for both their organizations and careers. Through the ACOG-Cefalo program, our team has spent two decades focusing on and refining the leadership competencies most useful to medical leaders in women’s healthcare. The data presented here indicate that the competencies selected are well-suited to this audience. As educators of extremely busy, practicing healthcare professionals, we have a keen interest in developing strategies for efficiently building skills through intensive training sessions and demonstrating the effectiveness of those approaches. The results from our previously published examination of the immediate positive impact of training on physician’s skills and confidence in their competenceCitation11 provides evidence that women’s healthcare physicians can “move the needle” of their learning for specific leadership skills in statistically significant and clinically meaningful ways. The data presented in this follow-up study support the hypothesis that those efforts are not only efficient and effective, but also produce longer-term impacts in broad competency areas, as evinced by the strong changes in competency scores for both knowledge and ability that we report. This study further confirms that the competencies focused on are relevant to the needs of physician leaders, are able to be taught in engaging and meaningful ways with practical applications, and that physicians report they subsequently use these skills frequently in their roles as healthcare providers and as healthcare leaders. Further, moving the needle in these competencies seems to be indicative of participant reports of positive career impacts for them as well. While we also provided robust post-program support that was individually oriented and self-directed, the intensity of a physician’s typical workload seems to hinder their ability to deeply engage in post-program reading or other types of ongoing leadership learning. Thus, an additional implication from our findings is that physician leadership training is best accomplished with structured approaches implemented in protected time, so that the physicians can focus on learning and skills acquisition without the pressing distractions of patient care and other daily duties.

This study demonstrates that all these goals can be achieved whether those training interventions are provided virtually or in-person. However, as we reported here, our experience suggests that stronger networks and connections are created with in-person programs and clearly participants prefer an in-person experience. Our work indicates that women’s healthcare physicians are ideal audiences for this leadership training, regardless of the platform of delivery. These physicians are eager learners, appreciate practical approaches, find relevance in the skills taught, subsequently use those skills, and relate the use of those expanded leadership skills to positive career impacts.

Limitations

Self-report measures do have the consideration of social desirability bias, however self-report measures have been used with a great deal of confidence for decades in situations when objective testing or personal observation is either not possible or practical.Citation6,Citation8,Citation11–14,Citation27,Citation34,Citation36,Citation37 In settings such as post graduate courses focusing on professional leadership development, self-report measures are quite appropriate. Identifying the factors that make virtual training more alluring to potential participants would provide useful insights, however that was not the focus of this study. While as program faculty we have an understanding of how to successfully convert in-person leadership training to virtual, such detailed exploration is beyond the scope of this report and our findings fail to give us insight into why physicians might choose one format over another. It would have been interesting to study the variety of ways the Whova App could have been useful post-program, however these two groups of physician participants engaged only minimally with the App functions both during and after the program. Our data fail to provide insight as to why the App was not engaging to them; however, the 2022 Cohort made extensive use of Email post-program, which seemed to be their method of choice for connecting with one another. In hindsight, we wish we had included physician resilience as a stand-alone competency so that we could now have greater insight into how leadership training can help support physicians in this way, however that data was not collected.

Conclusion

From examining these data, we conclude that physicians can successfully engage in leadership training in both virtual and in-person formats, gaining significant skills which result in implementation of those skills in the ensuing months post-program. The learning appears to be “sticky”, which suggests that the investment in the process offers a return on the effort, resulting in both practice- and career-dividends to the physician. Both the increased attendance in the 2022 cohort and the many qualitative comments from the 2021 group supported the preference of these physicians for in-person training experiences. Although in-person training did not result in widespread significantly greater learning, self-reported retention, or skills use when compared to virtual training, there was a notable difference in networking, benefits for leadership opportunities, and post-program professional connections, and perhaps even a belief in learning effectiveness. Future research could explore how to foster stronger interpersonal connections and improve the desirability of virtual leadership development programs. In addition, future investigations might explore if the virtual environment struggles with work-based distractions, such as inability to focus, inability to take off work, and disruption of learning by co-workers.

Physician leadership training can be effectively deployed in either virtual or in-person formats, although these physicians clearly preferred the in-person experience. Training in either format can continue to expand skills, even when the learner enters the program viewing themselves as having a high degree of knowledge around topics and a high use of related skills. Given the statistically significant shifts in knowledge and skills across all competencies, we conclude that physicians benefitted from this equity-centered leadership development approach and viewed themselves as retaining those skills and continuing to implement those skills even six months later, regardless of whether their participation took place virtually or in-person.

Disclosure

Dr Claudia SP Fernandez reports that Mr. Ruben Fernandez, JD, is the co-author of It-FACTOR Leadership, a text used in the ACOG-Cefalo Leadership Institute and is related to the corresponding author. Mr. Fernandez also serves as an executive coach and faculty in the program. Dr. and Mr. Fernandez are related by marriage. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

Acknowledgments

Emilie Mathura, Suzanne Singer, Caroline Martin, Maya Chevalier, Wendy Rouse Rohin.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sadowski B, Cantrell S, Barelski A, O’Malley P, Hartzell JD. Leadership training in graduate medical education: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(2):134–148. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-17-00194.1

- Angood PB, Falcone CM. Preparing physician leaders for the future. American Association for Physician Leadership/Korn-Ferry White Paper; 2023. doi: 10.55834/wp.3106435376.

- van Diggele C, Burgess A, Roberts C, Mellis C. Leadership in healthcare education. BMC Medl Educ. 2020;20(Suppl 2):456. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02288-x

- Menaker R, Naumann KE, Reeve CE, Mellum KM, Rihal CS. The Importance of Physician Education. Engelwood, CO: Medical Group Management Association; 2022:1–13. Available from: https://www.mgma.com/articles/the-importance-of-physician-leadership-education. Accessed June 12, 2024.

- Frich JC, Brewster AL, Cherlin EJ, Bradley EH. Leadership development programs for physicians: a systematic review. J Gen Int Med. 2015;30(5):656–674. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-3141-1

- Geerts J, Goodall AH, Agius S. Evidence-based leadership development for physicians: a systematic literature review. Soc sci med. 2020;246:112709. 2019. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112709

- Gorrindo P, Powers AR, Tedeschi SK, Niswender K. Fulfilling our leadership responsibility.(leadership skills in physicians). JAMA. 2013;309(2):147. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.165720

- Fernandez CSP, Noble CC, Jensen ET, Chapin J. Improving leadership skills in physicians: a 6-month retrospective study. J Leadersh Stud. 2016;9(4):6–19. doi:10.1002/jls.21420

- Corbie G, Brandert K, Fernandez CSP, Noble CC. Leadership development to advance health equity. Acad Med. 2022a;97(12):1746–1752. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004851

- Hopkins J, Fassiotto M, Ku MC, Mammo D, Valantine H. Designing a physician leadership development program based on effective models of physician education. Health Care Management Rev. 2018;43(4):293–302. doi:10.1097/HMR.0000000000000146

- Fernandez CSP, Hays CN, Adatsi G, Noble CC, Abel-Shoup M, Connolly A. Comparing virtual vs in-person immersive leadership training for physicians. J Healthc Leadersh. 2023;15:139–152. doi:10.2147/JHL.S411091

- Fernandez CSP, Noble CC, Chandler C, et al. Equity-centered Leadership Training found to be both relevant and impactful by interprofessional teams of healthcare clinicians: recommendations for workforce development efforts to update leadership training. Consult Psychol J; 2022. doi:10.1037/cpb0000239.

- Fernandez CSP, Corbie-Smith G, Green M, Brandert K, Noble C, Guarav D. Clinical scholars: effective approaches to leadership development. In: Fernandez CSP, Corbie-Smith G, editors. Leading Community Based Changes in the Culture of Health in the US: Experiences in Developing the Team and Impacting the Community. London: InTech Publishers; 2021a:9–28.

- Fernandez CSP, Green M, Noble CC, et al. Training “pivots” from the pandemic: a comparison of the clinical scholars leadership program in-person vs. virtual synchronous training. J Healthc Leadersh. 2021b;13:63–75. Volume 2021(b):13 Pages.doi:10.2147/JHL.S282881

- Corbie G, Brandert K, Noble CC, et al. Advancing health equity through equity-centered leadership development with interprofessional healthcare. J Gen Internal Medicine. 2022b;37(16):4120–4129. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07529-x

- Henry E, Walker MR, Noble CC, Fernandez CSP, Corbie-Smith G, Dave G. Using a most significant change approach to evaluate learner-centric outcomes of clinical scholars leadership training program. Evaluat Prog Plann. 2022;Volume 94:102141. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2022.102141

- Edmondson AC. The Fearless Organization. John Wiley & Sons; 2018.

- Rangachari P, L Woods J. Preserving organizational resilience, patient safety, and staff retention during COVID-19 requires a holistic consideration of the psychological safety of healthcare workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):4267. doi:10.3390/ijerph17124267

- Shanafelt TD, Gorringe G, Menaker R, et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(4):432–440. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.01.012

- Shanafelt TD, Makowski MS, Wang H, et al. Association of burnout, professional fulfillment, and self-care practices of physician leaders with their independently rated leadership effectiveness. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(6):e207961. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.7961

- Kain N, Jardine C. “Keep it short and sweet”: improving risk communication to family physicians during public health crises. Can Fam Physician. 2020;Vol 66:e99. MARCH | MARS 2020 |.

- Nikseresht A, Hajipour B, Pishva N, Mohammadi HA. Using artificial intelligence to make sustainable development decisions considering VUCA: a systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29(28):42509–42538. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-19863-y

- Worley C, Jules C. COVID-19’s uncomfortable revelations about agile and sustainable organizations in a VUCA world. J Appl Behav Sci. 2020;56(3):002188632093626. doi:10.1177/0021886320936263

- Pang EM, Sey R, de Beritto T, Lee HC, Powell CM. Advancing health equity by translating lessons learned from NICU family visitations during the COVID-19 pandemic. NeoReviews. 2021;22(1):e1–e6. doi:10.1542/NEO.22-1-E1

- Coen-Sanchez K, Ebenso B, El-Mowafi IM, Berghs M, Idriss-Wheeler D, Yaya S. Repercussions of overturning Roe v. Wade for women across systems and beyond borders. Reprod Health. 2022;19(1):184. doi:10.1186/s12978-022-01490-y

- D’Cruz JR. Is the graduate education model inappropriate for leadership development? HealthcarePapers. 2003;4(1):69–90. doi:10.12927/hcpap.16899

- Fernandez CSP, Noble CC, Jensen ET, Martin L, Stewart M. A retrospective study of academic leadership skill development, retention and use: the experience of the Food Systems Leadership Institute. J Leadership Education. 2016;15(2 Research):150–171. doi:10.12806/V15/I2/R4

- Fernandez CSP, Noble C, Jensen E. An examination of the self-directed online leadership learning choices of public health professionals: the MCH PHLI experience. 2017. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2017;23(5):454–460. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000463

- Henry E, Chandler C, Laux J, et al. Evaluating leadership development competencies of clinicians to build health equity in America. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2023;44(2):90–96. Spring2024. doi:10.1097/CEH.0000000000000526

- Zoom Video Communications, Inc. Zoom meetings; 2020. Available from: www.zoom.us. Accessed June 12, 2024.

- Whova Event App; 2020. Available from: www.whova.com. Accessed June 12, 2024.

- FastTrack Leadership Library. Fast Track Leadership. Available from: WeTrainLeaders.com. Accessed 12 June 2024.

- QualtricsXM. [software]. Provo, UT; 2020. Available from: www.qualtrics.com. Accessed June 12, 2024.

- Lam TCM, Bengo P. A comparison of three retrospective self-reporting methods of measuring change in instructional practice. Am J Eval. 2003;24(1):65–80. doi:10.1016/S1098-2140(02)00273-4

- Lozano LM, García-Cueto E, Muñiz J. Effect of the number of response categories on the reliability and validity of rating scales. Methodology. 2008;4(2):73–79. doi:10.1027/1614-2241.4.2.73

- Pratt C, McGuigan WM, Katzev AR. Measuring program outcomes: using retrospective pretest methodology. Am J Eval. 2000;21(3):341–349. doi:10.1016/S1098-2140(00)00089-8

- Sprangers M, Hoogstraten J. Pretesting effects in retrospective pretest-posttest designs. J Appl Psychol. 1989;74(2):265–272. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.74.2.265

- Rohs FR. Response shift bias: a problem in evaluating leadership development with self-report pretest-posttest measures. J Agric Educ. 1999;40(4):28–37. doi:10.5032/jae.1999.04028

- Altman DG, Gore SM, Gardner MJ, Pocock SJ. Statistical guidelines for contributors to medical journals. BMJ. 1983;286(6376):1489–1493. doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6376.1489

- Dwivedi A, Mallawaarachchib I, Alvaradob LA. Analysis of small sample size studies using nonparametric bootstrap test with pooled resampling method. Stat Med. 2017;36(14):2187–2205. doi:10.1002/sim.7263

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2019.

- Nilaad SD, Lin E, Bailey J, et al. Learning outcomes in a live virtual versus in-person curriculum for medical and pharmacy students. ATS Sch. 2022;3(3):399–412. PMID: 36312802; PMCID: PMC9585697. doi:10.34197/ats-scholar.2022-0001OC

- Reddy GB, Ortega M, Dodds SD, Brown MD. Virtual versus in-person grand rounds in orthopaedics: a framework for implementation and participant-reported outcomes. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2022;6(1):e21.00308. doi:10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-21-00308.

- Abarghouie MHG, Omid A, Ghadami A. Effects of virtual and lecture-based instruction on learning, content retention, and satisfaction from these instruction methods among surgical technology students: a comparative study. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9(1):296. doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_634_19

- Fernandez CSP, Esbenshade K, Reilly C, Martin LC. Career trajectory in academic leadership: experiences of graduates of the food systems leadership institute. J Leadership Educ. 2021;Vol 20(Issue 3):75–84. doi:10.12806/V20/I3/R4

- Fernandez CSP, Lia Garman L, Noble CC, et al. Developing “Cohortness” in leadership programs operating in the virtual environment. Am J Distance Educ. 2022;36(2):135–149. doi:10.1080/08923647.2022.2057091