Abstract

Purpose

To develop healthcare professionals as clinical leaders in academic medicine and learning health system; and uncover organizational barriers, as well as pathways and practices to facilitate career growth and professional fulfillment.

Methods

The Department of Medicine strategic plan efforts prompted the development of a business of medicine program informed by a needs assessment and realignment between academic departments and the healthcare system. The business of medicine leadership program launched in 2017. This descriptive case study presents its 5th year evaluation. Competencies were included from the Physician MBA program and from specific departmental needs and goals.

Results

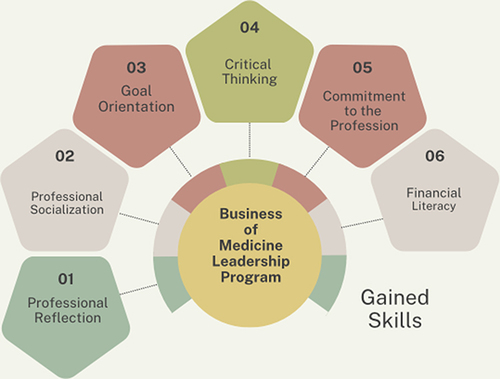

The program hosted a total of 102 clinical faculty. We had a 37% response rate of those retained at Indiana University School of Medicine. Overall, responses conveyed a positive experience in the course. Over 80% of participants felt that they gained skills in professional reflection, professional socialization, goal orientation, critical thinking, and commitment to profession. Financial literacy was overwhelmingly the skill that was reported to be the most valuable. Finance and accounting were mentioned as the most difficult concepts to understand. Familiar concepts included communication, LEAN, and wellness related topics. One hundred percent of participants said they are utilizing the skills gained in this program in their current role and that they would recommend the course to others.

Conclusion

Business of medicine courses are more common now with programs describing elements informed by health system operations. However, few programs incorporate aspects of wellness, equity, diversity, inclusion, and health equity. Our program makes the case for multiple ways to develop inclusive leaders through a focused five-month program. It also recognizes that to really impact the learning health system, health professionals need leadership development and leaders suited to work alongside career administrators, all aiming towards a common goal of equitable patient-centered care.

Introduction

The US healthcare system is complex. Its fundamental strengths and flaws have created complex integrated health care systems that operate under significant financial imperatives and have created convoluted operational areas.Citation1 When combined with academic medical centers, focused on the education, research, service missions in addition to clinical care, the organizational structures become highly matrixed. While academic health centers contribute greatly to health through these combined roles and missions, today, they present a very different set of skills, knowledge and demands from the physician workforce.Citation2

Patients treated at major academic health centers have up to 20% higher odds of survival than those treated at non-teaching hospitals. Academic health centers provide access to highly specialized services and advanced technologies for diagnostics and treatments.Citation3 As these centers continue to transform into learning healthcare systems, they will require the identification of specific areas where system complexities slow or inhibit progress and the development of solutions geared toward overcoming impediments and failures.Citation4 In order to achieve this we need a new type of leader.

These changes require professional development programs to prepare faculty physicians and other health professionals that can take on these roles. Systematic reviews have described the nature of leadership development programs.Citation5 Recently, a systematic review looked at 45 studies of physician leadership programs and only 8 of those programs targeted faculty physicians.Citation5 Current programs appear to share the following characteristics: 51% of programs in their review reported given protected time for the program, cohort sizes vary from 5 to 75, time commitments of 4 hours or less per week with asynchronous learning with reading assignments and projects.Citation5 Moreover, about a quarter of existing programs used a leadership competency model, but no single leadership competency was used by more than one organization. The common topics were leadership concepts, leading change, working, and developing others, communication skills, team building, and emotional intelligence.Citation5 Gaps in the literature indicate that few programs have published their work and longitudinal success, making it difficult to compare programs and assess the range of offerings.

Moreover, there has been a great need to expand leadership development opportunities in learning health systems, especially as health care is increasingly driven by complex priorities, impacted by persistent health disparities, and fast technology growth.Citation6 As we operate within a multiorganizational learning health system, the Business of Medicine program aligns with this goal while also covering general concepts associated with physician MBA programs in Indiana and across the nation.

This descriptive case study fills this gap in literature by describing a business-centered health professional leadership program while emphasizing crucial competencies and content, and reporting outcomes that demonstrate career growth for participants.

Program Description

In 2016, the Department of Medicine at Indiana University School of Medicine launched a strategic plan, prompted by realignment between academic departments and its associated healthcare system. A professional and leadership development needs assessment was conducted by leaders, which resulted in a list of business and leadership competencies needed at several administrative levels. The program was developed in partnership with Indiana University’s Kelley School of Business to provide expert instructors and content. The Business of Medicine Leadership Program officially launched in 2017. Initial financial support for the program was provided by the Department of Medicine.

Future iterations for individuals participating from the school of medicine were supported by the office of faculty affairs and professional development, individual clinical departments, or specific departmental arrangements with their own faculty members (2018–2021).

Furthermore, our institution and faculty operate within the Indiana Learning Health System Initiative (ILHSI) developed in partnership with six organizations, the Regenstrief Institute, two health systems, Indiana University Health (IUH) and Eskenazi Health (EH); Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM) and IU Fairbanks School of Public Health, and the Indiana Health Information Exchange (IHIE). The ILHSI represents a potential model for consolidating the academic health tripartite mission and moving beyond a single organization context to a joint mission of improving health and health care through advancing, applying, and disseminating knowledge.Citation7

Individuals joining the program from the health systems and school were supported by their own continuing medical education/professional development funds or by departmental/service line leads. The program is designed to provide clinical faculty and emerging leaders with a professional development opportunity that increases business acumen, leadership skills, and expertise. Initially, the program was aimed at academic physician leaders, and it has expanded to advanced practice providers with leadership roles or aspirations. The program’s premise was to develop and secure skills that match system, departmental, and school alignment needs:

Develop a toolkit of skills to enhance business acumen and leadership.

Leverage knowledge in order to position ideas more persuasively, increase team productivity, and lead others more effectively.

Strengthen overall business acumen and gain a better understanding of financial acumen, including the key frameworks, models and levers that drive organizational success.

Increase innovation capability via the development of an “intrapreneur” mindset, system, and roadmap.

Incorporate Lean/Six Sigma in the academic and practice arena.

The educational delivery model was hybrid through a learning management system (Canvas) and in person sessions. It consisted of 4–6 monthly sessions for 3.5–4 hours for highly interactive in-depth faculty-led sessions that allow for application and integration of the tools and knowledge (). Prior to each in-person session, participants engaged in asynchronous online, faculty facilitated sessions, utilizing videos, readings, assignments and discussion boards with peers and faculty to learn fundamentals and implement team action learning projects to apply concepts. The 2017 curriculum included the following content areas: Financial Acumen, Intrapreneurship and Innovation, Work-Life Integration, and LEAN training. Today’s curriculum has expanded to include Leading with wellness in mind and Strategic Equity.Citation8,Citation9

Table 1 Curriculum Overview

Curriculum changes were informed by program evaluations in addition to the need to develop inclusive leaders to advance equity patient-centered care.Citation9 Equity patient centered-care takes into consideration the specific needs of the patient and does not vary in quality based on personal identity, gender, geographic location, religion, sexuality, and socioeconomic status. The term reflects the need of the physician to demonstrate structural competency and inclusive leadership.

Methods and Program Evaluation

To date a total of 102 clinician faculty have participated in the program which expanded beyond the department of medicine to the school of medicine in 2018. Program evaluations were done yearly covering similar concepts as this 5th year evaluation. The program followed standard evaluations for faculty development programming developed by the Department of Medicine. The evaluation is based on two overall indicators: participant self-report (survey) and outcomes data (leadership roles). The evaluation assessed skills or attributes attained, difficulty or ease of concepts, time and effort commitment, program satisfaction and improvement suggestions, and demographic information. In addition, we collected information on current leadership roles and perspectives of the link of this program to career growth.

The evaluation included 28 questions, multiple choice, and open text. The evaluation was emailed to 90 participants within Indiana University School of Medicine and IU Health. Out of the total 102 participants of the program, there was a 11% employee attrition. The survey was opened for a period of 3-weeks with 1 Email reminder. The program evaluation does not meet the definition of research with human participants, does not involve experimental intervention, is anonymous and does not include identifiable information, and it is conducted as part of the standard practice in an educational setting. This is deemed exempt by IRB regulations and Indiana University School of Medicine (#22654).

Results

A total of 39 individuals participated in the evaluation for a 37% response rate of those retained at Indiana University School of Medicine ().

Table 2 Business of Medicine Leadership Program

Overall, responses conveyed a positive experience in the course. Over 80% of participants felt that they gained skills in professional reflection (94%), professional socialization (89%), goal orientation (83%), critical thinking, (89%) and commitment to profession (83%) (see ). Financial literacy was overwhelmingly the skill that was reported to be the most valuable, and most comments included references to the value of finance language and budgeting tools and skills. However, finance and accounting were also mentioned as the most difficult concepts to understand and required the longest preparation time prior to their in-person session. Familiar concepts included communication, LEAN, and wellness related topics. One hundred percent (100%) of participants said they will utilize/are utilizing the skills gained in this program in their current role and that they would recommend the course to others.

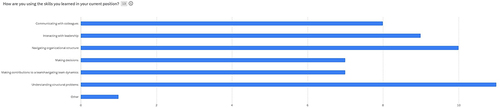

In addition, participants were asked if they were currently in a leadership role (8). Those individuals felt that the program helped them obtain their current role and were also asked how they were using the skills learned? (). Most individuals highlighted a new understanding of the structural problems within a complex LHS and how these skills help them navigate these structures.

Moreover, summarizes participant comments when asked if they felt that the program helped them obtain their current leadership roles? Responses were positive and suggest not only knowledge and skills gained, but also confidence.

Table 3 Do You Feel the Program Helped You Obtain Your Current Position?

When asked if the course should be part of medical education or residency and fellowship training, 67% agreed that it would be a valuable addition. Opportunities for the course were noted in relation to leadership mentoring opportunities (over half stated that they had not reached out to a potential mentor-leader in the health system), continued professional development in diversity, equity and inclusion-inclusive of health equity, and additional discussions towards career planning within the health system.

Departmental and school reports indicate that 59 participants were from the department of medicine (63% of total program participants). Thirty-three percent of all Department of Medicine participants have attained a leadership role of director and above within the school of medicine and health care systems affiliated with the institution. Another 13.3% from other departments across the school has also attained leadership role.

Discussion

The Business of Medicine Leadership program was launched out of a strategic initiative targeting the professional development of current and emerging leaders in the department of medicine, along with the recognition of the importance of realignment between the academic department and the health system. Findings overwhelmingly point to high satisfaction with content, delivery, and expertise. Moreover, the ongoing program evaluations provided an opportunity to continuously improve content, lesson plans and learning outcomes for each of the sessions.

In addition, program evaluations provided opportunities to expand learning modules to areas of interest and of current concern to department leaders and faculty in general, such as wellness and diversity, equity, and inclusion. More specifically, these additional topics reaffirm the department’s executive leadership model exemplifying Leading with wellness and equity in mind, meaning that along with inclusive excellence, every decision we make within the department shall consider the impact on wellness of our faculty, trainees, and staff; and we shall consider the inequitable impact these decisions may have on gender and racially-minoritized groups. Based on the current literature, we acknowledge that our program offers similar competencies. However, it also offered innovation in the addition of wellbeing, equity, and inclusion, and even healthcare lean.

It is important to also note the participation of women leaders in the program at nearly 40%. This aligns with the current faculty representation. Women participating have progressed to departmental, system, and academic leadership roles at the same rate as men. The longitudinal examination of leadership and career pathway offers a successful view of the business of medicine leadership program. With success also comes several challenges. First, we are approaching a saturation point for leadership development, therefore we have moved to offer this program every two years to make sure that participation remains steady amongst department of medicine faculty. Second, as cost of the program rises per participant, it challenges the department’s finite resources. More cost and revenue models need to be explored in order to remain a sustainable program. The desire to continue this program is unanimous among the department’s executive leadership and the school of medicine. Third, leadership positions are limited, therefore not accommodating all possible career goals. This also limits potential retention initiatives and efforts if career advancement is not possible. It is imperative that academic health centers consider what is next for these leaders and how to maximize their talents. Lastly, future evaluations and studies may include a comparative look at existing business of medicine programs around the country.

Limitations

Faculty development is recognized as essential in health professions institutions. Yet, program evaluation models do not measure the information educators want in terms of outcomes and impact. This is partly due to the evolving nature of programs, adaptation and reforms.Citation10 However, as is the case with this program, it is generally accepted that the outcomes and impact are situated at different levels, by the individual and the institution. Furthermore, despite efforts to obtain a higher response rate, the rate was 37%. Possible reasons were the timing of the evaluation, as it was done during a holiday period. In addition, the number of individuals that participated offered saturation as the themes of those responses were similar in nature. However, future efforts will be made to increase this response rate for the next longitudinal evaluation.

Conclusion

Business of medicine programs are more common now with programs describing elements informed by health system operations. Moreover, competencies developed tend to focus on clinical operations. However, few programs incorporate aspects of wellness, equity, diversity, inclusion, and health equity. Our program makes the case for multiple ways to develop inclusive leaders through a focused five-month program. It also recognizes that to really impact the learning health system, health professionals need leadership development and leaders suited to work alongside career administrators, all aiming towards a common goal of equitable patient-centered care.

Ethics Statement

The program evaluation does not meet the definition of research with human participants, does not involve experimental intervention, is anonymous and does not include identifiable information, and it is conducted as part of the standard practice in an educational setting. In addition, consent was obtained from the course participants, and guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki were followed. This is deemed exempt by IRB regulations and Indiana University School of Medicine (IRB #22654).

Disclosure

Dr Chemen Neal reports grants from Lupin Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work. The authors report no other conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Keroack MA. System integration: managing complexity to advance health care value. NEJM Catal. 2021;2(10). doi:10.1056/cat.21.0243

- Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on the Roles of Academic Health Centers in the 21st Century. In: Kohn LT, editor. Academic Health Centers: Leading Change in the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2004. Chapter 1, INTRODUCTION. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK221676/#. Accessed June 7, 2024.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. According to a recent study published in JAMA, when it comes to a Tangible Quality Measure That the Public Cares about -Mortality -Patients Fare Better at Teaching Hospitals. Available from: https://www.aamc.org/media/30601/download. Accessed February 5, 2024.

- Institute of Medicine (US) and National Academy of Engineering (US) Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Health Care. Engineering a learning healthcare system: a look at the future: workshop summary. In: Healthcare System Complexities, Impediments, and Failures. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011:3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK61963/. Accessed June 7, 2024.

- Frich JC, Brewster AL, Cherlin EJ, Bradley EH. Leadership development programs for physicians: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):656–674. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-3141-1

- Kilbourne AM, Schmidt J, Edmunds M, Vega R, Bowersox N, Atkins D. How the VA is training the Next-Generation workforce for learning health systems. Learn Health Syst. 2022;6(4):e10333. doi:10.1002/lrh2.10333

- Schleyer T, Williams L, Gottlieb J, et al. The Indiana Learning Health System Initiative: early experience developing a collaborative, regional learning health system. Learn Health Syst. 2021;5(3):e10281. doi:10.1002/lrh2.10281

- Sotto-Santiago S, Ansari-Winn D, Neal C, Ober M. Equity+ wellness: a call for more inclusive physician wellness efforts. MedEdPublish. 2021;10(99):99. doi:10.15694/mep.2021.000099.1

- Sotto-Santiago S, Ober M, Neal C, et al. Leading with wellness in mind: lessons in academic leadership during a pandemic. 2021. Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/1805/28001.

- Fernandez N, Audétat MC. Faculty development program evaluation: a need to embrace complexity. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2019;10:191–199. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S188164