Abstract

Background

The significant health development achieved in Palestine last decades has been lost, in Gaza particularly. This requires fundamental health system reform and rebuilding, including health workforces. Strengthening health workforces involves essential elements: leadership, finance, policy, education, partnership, and management. The current unprecedented catastrophe in Gaza and overall instability in Palestine show the utmost necessity for rethinking and reforming all pillars of the already collapsed health system, including the workforce. Health Workforce Accreditation and Regulation (HWAR) standardizes healthcare evaluations, representing a critical research area in Palestine due to limited existing knowledge.

Objective

This study aims to enhance understanding of the HWAR in Palestine, and identify gaps and weaknesses, thereby enhancing the HWAR’s development and optimization.

Methods

This qualitative study used an inductive approach to explore the landscape of HWAR. Data were collected from October to November 2019, when 22 semi-structured in-depth interviews - were conducted with experts, academics, leaders, and policymakers purposely selected from government, academia, and non-governmental organization sectors. Data analysis, namely, thematic and ground theory, was performed using Excel and MS programs.

Findings

The study revealed an absence of transparent governance and ineffective communication within HWAR systems. National policies and guidelines are problematic, with HWAR mechanisms fractured and needing reform. Licensing for healthcare workers hinges on local education, while monitoring and evaluation of HWAR are deficient. Some institutions adhere to HWAR standards, yet widespread updates and applications are necessary. Coordination among educational, accreditation, and practice sectors is non-systematic. Adequate human resources exist, but we need to improve HWAR management. Operational and political challenges limit HWAR, leading to a focus on immediate responses over sustainable system integration.

Conclusion

Boosting HWAR is critical for Palestine, especially after the ongoing conflict and humanitarian crisis that led to the dysfunction of the entire health system facilities. A collaborative strategy across sectors is needed to improve governance and outcomes. It is essential to foster strategic dialogue among academia, regulatory entities, and healthcare providers to enhance the HWAR system. Further study on HWAR’s effectiveness is recommended.

Introduction

Healthcare workforces (HCWs) play a vital role in the efficiency and effectiveness of health systems (HSs). They are recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a critical player in achieving better Universal Health Coverage (UHC), taking into consideration the quality, accessibility, availability and acceptability of these workforces.Citation1,Citation2 Health Workforce Accreditation and Regulation (HWAR) systems and programs assess the performances of HCWs against national and international standards as a way to enhance the quality of care in the era where under-resourced HSs are becoming a universal threat to humans and finances.Citation3,Citation4 Regulatory mechanisms control HCWs through governance, policies, and procedures through several activities, such as licensing, accreditation, and regulation.Citation5,Citation6 Several needs drive the establishment of HWAR, but primarily the need to improve and maintain quality care.Citation7,Citation8 HWAR programs are believed to enhance the sustainability of HCWs by improving providers’ satisfaction, productivity and retention rates and addressing workforce shortages.Citation9 Regulating HCWs has also become a global need. WHO has announced that a shortage of 10 million health workers is anticipated, with low- and lower-middle-income countries being mostly affected by 2030.Citation10 HWAR programs are also crucial in crisis management, which was recently proven during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Adaptive methods were rapidly created in response to the pandemic in areas where supply shortages and healthcare providers were of utmost importance.Citation11 Despite the established benefits of HWAR systems, many countries still need governance systems or have systems with limited transparency and accountability.Citation12 Furthermore, several nations still need more healthcare workers. For example, it is projected that by 2030, Africa will require the regulation and training of an extra 3 million health workers to meet anticipated demand. This highlights the significance of regulating the HCW and developing innovative strategies for accreditation.Citation13

Among the barriers are skepticism of healthcare providers regarding the impact of such activities, lack of knowledge about how regulatory mechanisms work, their impact and in what context they must be used, implementation cost, and inconsistent results demonstrating the impact of accreditation programs despite the tremendous financial investment.Citation3,Citation9,Citation14,Citation15 Additionally, there is disagreement over who and what needs to be regulated.Citation16 A practical and sustainable regulatory system depends on a clear, well-designed governance framework. This requires the cooperation of many levels of government, regulators, and regulated bodies in an organized manner.Citation16 Regulatory bodies vary according to the country’s policies, with a growing tendency toward shaping the regulatory landscape instead of having a single regulatory body controlling all aspects of the field.Citation6,Citation17 For instance, in some countries, the regulation of health practitioners is directly assigned to the Ministry of Health (MoH). In contrast, in other countries, it is managed by a subdivided board or council that works with the MoH.Citation16

Recent research highlighted essential gaps that exist in HWAR systems, including but not limited to fragmented and inefficient regulatory frameworks, rigorous educational programs, limited practice areas and occupation-specific reimbursement strategies. Furthermore, it was discovered that for HWAR systems to function effectively, national needs and adequate resources to match the intended environment should be considered.Citation18 According to recent evidence, continuous and rigorous evaluation of the utilized HWAR processes was also highly encouraged. Leslie et al discussed establishing strategic monitoring parameters for HWAR systems to assess how innovations and regulatory actions affect accomplishing health workforce and health systems objectives.Citation19

In the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMRO), including Palestine, the HCW status is similar to the global situation, with additional challenges. According to the EMRO, the main challenges that face the region are inadequate employment capacities, geographic differences, low retention rates in rural areas, performance and motivation of HCWs, skill imbalances, and inadequate management of health workers’ emigration.Citation20 The Palestinian Ministry of Health is actively working on implementing effective strategies by assessing the needs of individuals and organizations and evaluating new policy benefits. However, there is limited knowledge about national policies and structures for the health system accreditation in Palestine.Citation21 The situation is still more challenging in Palestine due to additional obstacles facing the regulatory authorities and HCWs. Despite global efforts to address HWAR, the suggested solutions and recommendations cannot always be extrapolated to the HS in Palestine, as the challenges are not experienced elsewhere. For example, the policies of the Israeli Occupation, including over 500 checkpoints and the separation wall in the West Bank, hinder the delivery of medical supplies and healthcare, advance HS infrastructure, and even prevent practitioners from entering the country.Citation22 Moreover, the ongoing armed conflict and humanitarian crisis coupled by strict blockage on Gaza have yielded an enormous gap between supply and demand, where medical teams with significant staff shortages were forced to respond to large numbers of casualties with minimal supplies available.Citation22,Citation23 According to a WHO 2016 report, each month, the Israeli Occupation refuses travel permits for almost a third of Gazan patients who apply to seek medical treatment.Citation24 These troubling facts necessitate understanding the current HWAR systems in Palestine since clear, well-defined standards and frameworks of HWAR systems are urgently needed to overcome these challenges. Part of the extended research project, the first paper explored the level of understanding among health policy-makers, academics and experts regarding the definition and conceptualization of the HWAR concept, assessed the perceptions of stakeholders about the factors affecting the HWAR system in Palestine, and proposed actionable recommendations that strengthen the national HWAR in Palestine. This current study describes the policy landscape and structure of HWAR systems in Palestine, a topic that has not been addressed previously.

Methods

Study Design and Sampling

A qualitative research approach was adopted in this study. An inductive approach based on semi-structured interviews with key informants was used to explore and describe the conceptual perceptions, governance policy, technical practices, resources and capacity, gaps, and solutions for HWAR in Palestine. This paper presents the findings related to the policy landscape and structure of the HCW accreditation and regulation system. Two papers presenting other aspects of the results were previously published, and this current study is part of this extended national HWAR assessment.Citation21,Citation25 This paper presents the findings related to the policy landscape and structure of the health workforce accreditation and regulation system. The design and methods of the two previous studies and this study were similar.Citation21,Citation25 The study methods are described here in brief. This research adopted a purposive sampling method to select key informants across governmental, academic, and non-governmental sectors in the Gaza Strip and West Bank, focusing on those involved in Health Workforce Accreditation and Regulation (HWAR) operations within Palestine. Selection criteria required informants to possess over five years of field experience and to provide informed consent. The participant informed consent was taken from each expert and accepted the interview invitation that was sent via email. Additionally, there was a question asked to all experts that assured their participation prior to the conduction of the interview. Ethical clearance was granted by the Helsinki Committee (IRB no PHRC/HC/656/19), after which 22 individuals were invited to participate via email. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with an equal number of informants from both the West Bank and Gaza Strip, with each session lasting between 45 and 90 minutes and occurring from early October to mid-November 2022. The participants’ responses were treated, managed, and analyzed anonymously by giving each participant a particular clarification that refers to her/his responses.

The sample comprised 22 participants representing a blend of perspectives from the primary sectors responsible for managing HWAR, ensuring a comprehensive assessment of policies and practices. The qualitative interviews were structured around the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) and facilitated by two seasoned researchers. The process included initial phone communication for study explanation, consent, and sharing of interview guidelines, followed by face-to-face interactions.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using MAXQDA 12 software complemented by Excel, adhering to a thematic analysis framework. This involved a six-stage analytical process: coding, searching, reviewing, defining themes, selecting representative quotes, and integrating findings with relevant literature. The analysis aimed to discern patterns and develop a theoretical understanding of the HWAR monitoring and evaluation system’s effectiveness within Palestinian healthcare governance. The study’s rigorous analytical methodology was fortified by dual-researcher involvement, ensuring the integrity and thoroughness of the interpretive process. Participants’ rights were upheld through informed verbal and written consent.

Results

HWAR Governance and Stewardship

The study participants were asked about the presence of an HWAR system and associated governance mechanisms; the majority responded that there is an existing system. However, there needed to be a consensus on the governance mechanisms and the interaction among different HWAR governance stakeholders. Most participants stated that HWAR was primarily governed by the MoH and complemented by the work of the professional unions/syndicates.

Yes, there is a strict and clear system which is composed of Ministry of Higher Education (MoHE) for giving accreditation, MoH the gives licence, The Palestinian Medical Council (PMC) works only with specialist doctors and those that pursued postgraduate certifications Academic Expert 3.

Several participants mentioned the contribution of the MoHE, PMC, and two MoH departments: the General Administrations of Hospitals and Primary Health Care. However, the complementarity mechanism between these entities and their overlap with the MoH in HWAR governance remained to be determined. Some participants highlighted that HWAR governance was more structured in the licensing and accreditation of newly graduated/alum HCWs but was vague across other parts of the HWAR governance cycle.

The structure is clear at first but disappears upon entering the labour market NGO Expert 2.

It is worth noting that only one participant highlighted the legal governance framework of HWAR, mentioning the Legislative Council Act of 2004. The Legislative Council Act was amended and published in 2004. In that act, public health law No. 20 also came up to detail the legislations and regulations related to health in Palestine, including the health workforce. Several participants expressed that there is either no or an unclear fragmented system. The participants mentioned that many structures and procedures must be fully operational and functional. Additionally, the coordination issue between HWAR governance stakeholders was raised multiple times.

Of course, there is no governance, no administrative organization, and no coordination between unions United Nations Expert 1.

The geographic context in Palestine influenced the participants’ views on HWAR. Many participants from Gaza highlighted that emergency and urgent needs-driven decision-making on HWAR was implemented more than sustainable evidence-based HWAR decision-making. The instability of the governance system, the need to enforce existing laws and regulations, and the need to establish a governance entity were also raised.

Yes, in a system, but not the system it should be. There is no complementarity between education and the practice of health professions” Government Expert 10.

Policy

Concerning national HWAR policies, guidelines, or manuals in Palestine, there was a similar range of responses echoed by study participants. Half of the participants acknowledged the existence of strategy or guidance for HWAR but that it needs further review, enforced implementation, or complementation by other practical procedures.

There are strategies, and there is a National Observatory for cadres, but to the best of my knowledge, there are no guidelines for managing accreditation and legalizing to licence health personnel Government Expert 11

Approximately one-third of the participants stated that there is a need for a national strategy or guidelines on HWAR.

I think there is no national or institutional guide or guidelines for managing the HCW because of political instability, lack of strategic vision, and focus on crisis management NGO Expert 1

One participant pointed to the plan to develop the first integrated strategy for managing health personnel in 2020, which aims to address the gaps and pitfalls endemic to the current policies and structures.

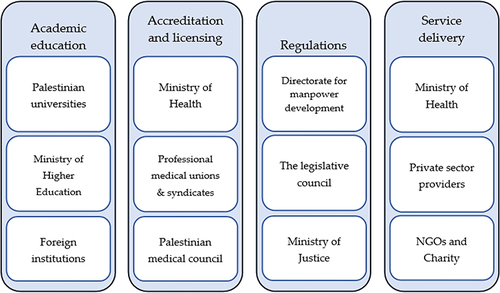

Mapping of HWAR Stakeholders

Participants responded to questions on HWAR governance stakeholders and their roles, affirming the centrality of the MoH to HWAR governance. Some participants highlighted the complementarity in HWAR governance between various departments and institutions, including professional unions, the Unit for Accreditation and Licensing in the MoH, the General Administrations of Hospitals and Primary Health Care, the General Administration for Administrative and Financial Affairs, PMC, MoHE, and the General Directorate for Human Resources Development. In , HWAR stakeholders are underlined according to their functions.

Some participants suggested that there should be more engagement with other institutions that are key to HWAR governance, such as the Legislative Council and the Ministry of Justice.

The need for a specialized body or institution to coordinate, standardize and monitor HWAR and its governance was highlighted by some participants.

In theory, the MoH, but in reality, there is none. Unions, the PMC, the MoHE, educational and academic institutions, and the MoH all play important roles and depend on each other. There is no single entity managing the issue Government Expert 10.

Some participants also highlighted the governance gap in accreditation compared to licensing. Participants illustrated that the MoH takes the lead on HWAR governance in licensing, but no entity or institution is expressly responsible for accreditation.

I think until now there are no specialized bodies related to accreditation, but there is a licensing unit in the MoH Academic Expert 2.

The specific relationship between the MoH and the professional unions/syndicates was highlighted by many participants, particularly the need to strengthen communication and coordination between professional unions and the MoH in a sustained, regular, and frequent manner. The complex interaction between the MoH and professional unions varies and depends on the form of regulation or accreditation needed. For example, the authentication of educational certificates is governed by the MoH, while professional unions or syndicates govern the authentication of professional experience. Additionally, the fact that there are professional union members who are HCWs working outside the MoH showed a gap in the organization of the structure.

Who governs is the MoH in terms of the public and of laws, but in practice, it is governed by the unions and the requirements for obtaining a licence. The MoH is concerned with the authentication and documentation of certificates. The unions are responsible for the documentation of practical experiences. There is coordination, but coordination is not full and continuous. There needs to be more union membership outside and inside the ministry. This thing is more of financial gains than organization and regulation of the process NGO Expert 2.

HWAR Process and Mechanisms

Participants recognized the HWAR processes and mechanisms of action, including accreditation, the licensing process, the system’s functionality, and regulations.

demonstrates the licensing process where many participants stated that workforce licences depend on whether the HCWs received their education in Palestine. Students or graduates who received their education in Palestine go directly to the licensing process, whereas those who received their education abroad must take a practical assessment. Many participants also highlighted that the licence cycle starts with the healthcare facility where the individual is applying to work, provided that this healthcare worker has professional union membership. The application is then referred to the MoH, which goes under review and is granted or denied approval by the Deputy Minister of Health. Finally, the application is referred back to the healthcare unit where it was first made. However, various participants also highlighted the gaps in licensing for rare and new specializations and flagged the need for transparent processes to issue licences to those specialists. One participant suggested that the absence of transparent licensing processes for such specializations may lead to challenges in introducing them to the HCW, pushing those health professionals to work abroad where regulations are more straightforward.

The mechanism is clear, so it starts from primary health care settings to clearance and licensing, then the deputy ministry for approval. However, rare specialities do not have a clear path; they can be given an exception Government Expert5.

However, one participant suggested that the process for HWAR of new specializations starts with an application to the MoHE. Many participants affirmed the gap between academic education and practice. In addition, the absence of a recertification process was flagged. Several participants also raised the issue of the lax legal system in enforcing regulation implementation.

Every profession is subject to its professional union or syndicate. There are no universal or similar regulations processes, and we need to build an established subsystem for each profession to be integrated into a unified, all-inclusive system United Nations Expert 1.

Quality Assurance and Check of HWAR

Most participants responded that there is either no monitoring, evaluation, and verification plan, or they are unaware if there is one. Only a few participants knew of existing plans and mechanisms that should have been implemented by the Department for Quality and Control at the MoH, yet these plans still need to be fully functional.

There is monitoring, but these indicators are not usually updated Government Expert 8.

Among the participants who stated there was no monitoring, evaluation, or verification plan for HWAR, some highlighted the need for a system and a clear policy that accommodates university graduates with market needs regarding quantity, quality, and specializations. Another frequently raised reason was the political divide contributing to legal and accountability gaps. The main repercussions of the political divide led to administrative, systems, and policy disintegration, fragmented regulatory systems, and a lack of collective unity and ideal political participation. In addition, participants pointed out that the distribution of services across primary, secondary, tertiary, and emergency care is randomly inconsistent and not planned based on evidence. Participants from Gaza highlighted the consequences of repeated crises on the fragile system and the influence of the siege and border restrictions on the movement of HCWs, especially those educated abroad. In more specific terms, some participants suggested that the absence of monitoring and evaluation is due to limited resources, the focus on emergency response, and the increased number of HCWs who cannot quickly be followed manually. Participants needed to be more confident in the presence of a human resources system with the capacity to perform such roles and responsibilities.

At the MoH, we cannot find monitoring, verification, and evaluation for the HWAR processes and practices because of issues like external dictations, the huge number of graduates that staff cannot monitor and follow, lack of resources, and that senior MoH staff focus on emergency response, including a shortage of drugs, then other issues” Government Expert 4.

A Framework for Standardizing Accreditation and Regulations

Participants needed a cohesive idea of the presence of accreditation and regulation frameworks and standards, how widely they are applied, and why. One-quarter of the study participants stated that there are clear standards for accreditation and regulation of HCWs.

There is a clear standard for every profession in the health sector Academic Expert 4.

Half the study participants indicated that existing accreditation and regulatory standards are well applied, except for rare specializations. They added that most of these standards must be updated, reviewed, and enforced to be applied on a larger scale. Participants added that these limitations are due to the need for more financial resources, evidence-based planning, and/or strategy and vision. It is also important to highlight that participants stated that not all HCWs have professional unions, especially those in new specializations. Several participants pointed out that regulations are applied more in medical professions and, to a lesser extent, in pharmaceutical professions.

Each profession has specific accreditation frameworks based on the needs of the MoH. However, they are not fully implemented because of insufficient financial resources NGO Expert 1.

Approximately a quarter of the study participants needed to be made aware of the presence of standards for accreditation and regulations, or they stated that there were no standards that they were aware of that.

HWAR Practices and Procedures

Responding to questions on the path from education to practice, most participants expressed that they needed to be made aware of procedures aimed at coordinating the transition from education to practice or were not satisfied with the current status of such procedures. Many reports need more systematic, structured communication and coordination between educational, regulating, and workplace-based stakeholders. The need for continuing education and a closer review of educational programs and curricula were flagged. Some participants suggested that any dialogue between the MoH and the education sector is based on personal initiative and needs to be carried out in a structured, effective way. Participants reported that after accreditation, there has yet to be a follow-up or examination to investigate the quality of the practice of the health service providers.

I have not heard of this role. Higher education has a role in academic programs, but after granting the licence to the programs, there is no interference Academic Expert 6.

However, several participants expressed their satisfaction with the application of accreditation and regulation in the transition from education to practice.

I think it is applied strictly and well Government Expert 7.

When addressing the quality of the HWAR practices performed, half of the study participants stated that current HWAR practices are acceptable on a fundamental level but are low quality and need improvement, including better communication between stakeholders. Many participants highlighted that HWAR practices are strong at the start of the accreditation process and become weaker and more fragmented once HCWs enter the labour market.

Practices are strong in the beginning but lessen after entering into practice Government Expert 11.

Several participants responded that the current HWAR practices must be more appropriate because of the missing framework for the transition between education and employment. However, some participants also stated the opposite, asserting that the current HWAR practices are appropriate. One participant highlighted the importance of HWAR and its application to decision-making.

I think the application of the practice performed in high quality and appropriately because he thinks it is a critical issue to the policymaker. Government Expert 4.

Human and Financial Resources and HWAR

In response to questions concerning the adequacy of staff and financial resources devoted to the HWAR process, more than half of the study participants stated that staff and personnel are somewhat qualified. Nevertheless, more development and improvement in capacity and skill are deeply needed. Along with capacity issues, there is a need for more staff managing HWAR in crucial governance institutions.

Based on existing employment standards, they are qualified but need to be developed because they are still below the required level NGO Expert 1.

Most participants focused on human resources rather than financial or operational resources. However, several participants highlighted the impact of limited financial resources on developing HWAR capacities. Others also mentioned that we need to improve operational, political, and logistic resources and that we should be able to carry out an overall strategic plan rather than only responding to emergencies.

There are no competencies and no sufficient preparation for development. There is a material problem, no doubt. Logistical capacity needs to be rearranged and reorganized. Academic Expert 1.

Discussion

Overall, Palestinians need to improve the HWAR in Palestine now more than ever. The health system in Palestine is one of the most fragile worldwide since it is largely constrained in the West Bank and has completely collapsed in Gaza due to the current wide-ranging armed conflict and humanitarian crisis that caused so far more than 200 health workforces killed. The previous and ongoing Israeli occupation practices make the health system and its pillars weak and dysfunctional, and this imposes the importance of essentially considering the HWAR in the national efforts of rebuilding and reforming the health system, especially the health system in Gaza. The governing system for HWAR was controversial and described as fractured, improperly applied, not inclusive, and requiring essential reform. National HWAR policy and guidelines exist in the national health strategy developed by the Palestinian MoH, but they need to be implemented more and require substantial updates. Moreover, HAWR mechanisms need to be more widely understood due to the need for a unified legal and procedural framework. Within the study, multiple governing bodies that have weak, uncoordinated, and independent roles were mentioned. These factors have resulted in accreditation and regulation being performed at the lowest level of quality. HWAR resources and capacity face a severe deficit except for the availability of qualified personnel capable of governing.

Clear and unified healthcare workforce processes and mechanisms are crucial for all specializations. However, gaps in the licensure process have led practitioners to seek jobs abroad. Uncoordinated licensing procedures may hinder skilled practitioners’ and HCWs’ entry into healthcare labour markets. This issue is consistent with previous reports on regulatory mechanisms in Palestine, indicating little progress and the need for more interventions.Citation26 Additionally, the need for recertification and the gap between education and practice were reported, which is, in fact, a global problem.Citation16 A coherent system that aligns educational institutions with practical needs is needed in Palestine. Gaps in the interaction between higher education institutions and MoH are also problematic. Universities’ educational curricula are generally developed by the college following MoHE requirements, with little to no involvement of MoH.Citation27 After graduation, only a few practical and accredited postgraduate specialization programs are available, mostly for physicians, as specialties and subspecialties. Not all have clear and comprehensive curricula.

Current decision-making related to the workforce is based on emergency needs, needing a well-planned, evidence-based approach. A specialized governance body is needed to coordinate, standardize, and monitor HWAR while coordinating stakeholders, ministries, syndicates, and academic institutions to build an integrated national accreditation and regulatory body. This body should have a shared vision, well-established guidelines, and a clear accreditation and regulation policy for best practices and effective mechanisms.Citation16

The operational procedures and processes for overseeing, auditing, and assessing -HWAR programs in Palestine are lacking, similar to most developing countries.Citation28,Citation29 The lack of a policy framework guiding academic institutions and graduates in employment based on labour market demands is a significant issue, as seen in low- and middle-income countries.Citation28 The political divide contributes to legal and accountability gaps, hindering unifying quality assurance plans. The random and inconsistent distribution of resources is another cause that is consistent with the EMRO report 2017.Citation15 Political crises contribute to the system’s fragility, particularly in the Gaza Strip. Due to these frequent and intense crises decisions related to healthcare services and HCWs are usually urgent needs-driven, leaving no room for a coherent governance system and consistent HWAR improvement. In 2015, 13% of global attacks on healthcare facilities/workers occurred in Palestine, ranking second only to the Syrian Arab Republic.Citation20 In 2023 alone, tens of healthcare facilities were attacked in Gaza, and hundreds of HCWs were killed. Several universities were severely affected, and tens of academics were also lost.Citation30,Citation31 This high number of attacks poses risks to healthcare workers’ well-being, mass casualties, resource needs, and a deviation from long-term health development goals.

A quarter of study participants stated that there are clear standards for HWAR, but the remaining responses needed more knowledge or closer monitoring and follow-up. Palestine’s accreditation and regulation process is well organized initially but weakens after a few steps. Not all professions have unions, a global issue.Citation32,Citation33 To address this, regulatory bodies in Palestine need to revise the current system, allowing for improvement and innovation. Standardizing the framework of accreditation and regulations relies on cooperation between regulatory bodies to create clear guidelines.Citation16

Most participants stated that there needed to be more in the areas of practices and procedures. This result is inconsistent with the recent reports of growing efforts by the Palestinian MoH in this field. For example, the Accreditation and Quality Assurance Commission (AQAC) is the governmental semiautonomous body responsible for higher education accreditation in Palestine and is a member of an international quality assurance network.Citation34 For entry into the medical field, the MoHE determines the requirements for entry for local or foreign graduates.Citation34 The PMC, on the other hand, 1) puts in place qualification standards for the accreditation of health centres and hospitals that host training for physicians and 2) issues specialization certifications to qualified physicians who pass PMC’s assessments.Citation35 Additionally, one of the leading general directorates at the MoH, the General Directorate of Education in Health (GDEH), focuses on training, educating, and developing health workers’ abilities in Palestine. Since 2010, GDEH has been following the Continuing Professional Development (CPD) framework, which targets programs and training accreditation and continuous development of health workers. The MoH has even declared that participation in CPD is mandatory to renew a license to practice.Citation36 However, policy makers need to improve or better implement these efforts, considering that the majority of the experts in the field stated that there needs to be an adequate HWAR process from education to practice or continuing education. In fact, up until now, continuous education for HCWs has been optional to maintain the license, as evidenced by the lack of clearly enforced rules. It is generally provided by a few bodies, such as Juzoor and IMET2000, and only on a minimal spectrum of general topics. Thus, further awareness and implementation reinforcement are needed in this area. More than half of the experts stated that further development and improvement in healthcare workers’ capacities are needed. Additionally, the shortage of staff managing HWAR was raised by many participants, an issue that makes the implementation of HWAR in Palestine even more challenging.

This study is the first to examine Palestine’s HWAR landscape and structure, providing a comprehensive view of both the West Bank and Gaza. It offers opportunities for future research on the effectiveness of existing mechanisms, particularly the Ministry of Education process and syndicates. Future research should examine HWAR mechanisms across decentralized administrative units and involve more policy, managerial, and clinical participants.

Limitations

The limited literature needs to improve the robustness of the literature and desk review on HWAR within Palestine. The limited quantitative data in this area restricted the triangulation of analysis. Finally, key stakeholders’ possible biases and affiliations may have overrepresented vital barriers.

Conclusion

Palestine has achieved significant progress towards the overall care and improvement of the health and well-being of its citizens. But this progress no longer exists, especially in the health system in the Gaza Strip, due to the systematic and direct attack of health workers, destruction of health system facilities, and deficit of needed resources. The comprehensive development that all social systems, including health, gained in Gaza last decades has vanished due to the mass human loss and radical destruction of pillars of society and its infrastructure during the current horrific war. However, to sustain this progress in the West Bank and to restore it in the Gaza Strip, strategic rethinking and wise investment in HWAR, as a key pillar of the health system, should be a national health priority to policymakers, especially in the strategies they build to attain UHC’s goals with more focus on Gaza. The current HWAR system is unclear to many stakeholders, and how different organizations and institutions interact remains vague. Improved communication, an effective information system for HWAR, and the inclusion of critical stakeholders are recommended to ensure that all actors are actively involved. Experts have yet to reach a consensus on the state of HWAR governance, accountability frameworks, and transparency in Palestine. Most HWAR gaps and challenges are treatable, including environmental factors and system inefficiencies. We can achieve this by building a clear strategic framework for HWAR in Palestine and improving the limited capacity for monitoring, evaluating, and overseeing HWAR programs. Effective design, planning, oversight, and reporting mechanisms will yield better HWAR results from both the supply and demand sides. An intersectoral approach is critical to strengthening the current HWAR system in Palestine to address disintegration and coordination. Academic institutions, regulating bodies, and healthcare providers, including patient associations, professional unions, and syndicates, should engage in a strategic dialogue on tackling the significant gaps and advancing the HWAR system.

Finally, it is essential to highlight the scarce evidence, studies, operational research, and anecdotal evidence concerning this topic. Further research is recommended to investigate the efficiency, effectiveness, and impact of the current HWAR practices, mechanisms, and systems. Diverse research methods that utilize economic costing in HWAR, mixed methods, forecasting and innovative methods are encouraged to explore this area further.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of the Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Helsinki Committee at the Palestinian Health Research Council (IRB no PHRC/HC/656/19).

Informed Consent Statement

Each participant received all relevant information regarding the study and was given the choice to participate. Their acceptance was initially verbal and documented by a signed informed consent form. Participant data were anonymized, and protection of their identity was included in the data management plan, analysis, and storage.

Author Contributions

MA contributed to the initiation and ideation of this study, design, and the oversight and management of the study. All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests in this work.

Acknowledgments

We thank all experts and institutions from the health sector in Palestine who participated and provided rich information to meet the study’s objectives.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sonderegger S, Bennett S, Sriram V, Lalani U, Hariyani S, Roberton T. Visualizing the drivers of an effective health workforce: a detailed, interactive logic model. Human Resour Health. 2021;19(1):32. doi:10.1186/s12960-021-00570-7

- Sonoda M, Syhavong B, Vongsamphanh C, et al. The evolution of the national licensing system of health care professionals: a qualitative descriptive case study in Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Human Resour Health. 2017;15(1):51. doi:10.1186/s12960-017-0215-2

- Hinchcliff R, Greenfield D, Westbrook JI, Pawsey M, Mumford V, Braithwaite J. Stakeholder perspectives on implementing accreditation programs: a qualitative study of enabling factors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):437. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-13-437

- World Health Organisation. Working for Health and Growth: Investing in the Health Workforce. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2016.

- WHO. Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: workforce 2030. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2016. Available from: http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/globstrathrh-2030/en/. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- Cometto G, Buchan J, Dussault G. Developing the health workforce for universal health coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;98(2):109–116. doi:10.2471/BLT.19.234138

- Mate KS, Rooney AL, Supachutikul A, Gyani G. Accreditation as a path to achieving universal quality health coverage. Globalization Health. 2014;10(1):68. doi:10.1186/s12992-014-0068-6

- Rooney A. Licensure, Accreditation, and Certification: Approaches to Health Services Quality. USA; 1999.

- Hastings SE, Armitage GD, Mallinson S, Jackson K, Suter E. Exploring the relationship between governance mechanisms in healthcare and health workforce outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):479. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-479

- WHO. Health workforce. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-workforce#tab=tab_1. Accessed December 28, 2023.

- Haldane V, De Foo C, Abdalla SM, et al. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from 28 countries. Nature Med. 2021;27(6):964–980. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01381-y

- WHO. The work of WHO in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: annual report of the Regional Director 2019. World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Licence: CC BY-NCSA 3.0 IGO. World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; 2020.

- Okoroafor SC, Ahmat A, Asamani JA, et al. An overview of health workforce education and accreditation in Africa: implications for scaling-up capacity and quality. Hum Resour Health. 2022;20(37). doi:10.1186/s12960-022-00735-y

- Algunmeeyn A, Alrawashdeh M, Alhabashneh H. Benefits of applying for hospital accreditation: the perspective of staff. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28(6):1233–1240. doi:10.1111/jonm.13066

- Alkhenizan A, Shaw C. Impact of accreditation on the quality of healthcare services: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31(4):407–416. doi:10.4103/0256-4947.83204

- WHO. Strengthening Health Workforce Regulation in the Western Pacific Region. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016.

- World Health Organization. Everybody’s Business – Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes: WHO’s Framework for Action. World Health Organization; 2007. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43918. Accessed August 1, 2024.

- Mahat A, Dhillon IS, Benton DC, Fletcher M, Wafulae F. Health practitioner regulation and national health goals. Bull World Health Organ. 2023;101(09):595–604. doi:10.2471/BLT.21.287728

- Leslie K, Bourgeault IL, Carlton AL, et al. Design, delivery and effectiveness of health practitioner regulation systems: an integrative review. Hum Resour Health. 2023;21(72). doi:10.1186/s12960-023-00848-y

- WHO. Framework for action for health workforce development in the Eastern Mediterranean Region 2017–2030. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; 2018.

- Najjar S, Hafez S, Al Basuoni A, et al. Stakeholders’ Perception of the Palestinian Health Workforce Accreditation and Regulation System: a Focus on Conceptualization, Influencing Factors and Barriers, and the Way Forward. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(13):8131. doi:10.3390/ijerph19138131

- Vitullo AMA, Soboh AD, Oskarsson JMA, Atatrah TMD, Lafi MMPH, Laurance TMA. Barriers to the access to health services in the occupied Palestinian territory: a cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380:S18–S9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60200-7

- Alkhaldi M, Meghari H, Alkaiyat A, et al. A vision to strengthen resources and capacity of the Palestinian health research system: a qualitative assessment. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26(10):1262–1272. doi:10.26719/emhj.19.096

- Keelan E. Medical care in Palestine: working in a conflict zone. Ulster Med J. 2016;85(1):3–7.

- AlKhaldi M, Najjar S, Al Basuoni A, et al. National health workforce accreditation and regulation in Palestine: a qualitative assessment. Lancet. 2022;399(Supplement 1):S23. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01158-8

- Pfeiffer MV. Vulnerability and the International Health Response in the West Bank and Gaza Strip: An Analysis of Health and the Health Sector. Jerusalem, Palestine: World Health Organization; 2001.

- The higher education system in Palestine. National report 2016. RecoNow & The European Commission. Available from: http://www.reconow.eu/files/fileusers/5140_National-Report-Palestine-RecoNOW.pdf. Accessed December 28, 2023.

- Dal Poz MR, Gupta N, Quain E, Soucat ALB. Handbook on Monitoring and Evaluation of Human Resources for Health: With Special Applications for Low- and Middle-Income Countries. World Health Organization; 2009.

- Riley PL, Zuber A, Vindigni SM, et al. Information systems on human resources for health: a global review. Human Resour Health. 2012;10(1):7. doi:10.1186/1478-4491-10-7

- United Nations Human Rights. Gaza, 2023: UN expert condemns ‘unrelenting war’ on health system amid airstrikes on hospitals and health workers. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2023/12/gaza-un-expert-condemns-unrelenting-war-health-system-amid-airstrikes. Accessed December 28, 2023.

- University World News; 2023. Available from: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20231012162739531. Accessed December 28, 2023.

- Nancarrow SA, Borthwick AM. Dynamic professional boundaries in the healthcare workforce. Sociol Health Illness. 2005;27(7):897–919. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2005.00463.x

- Davies J, Hughes R, Margetts B. Towards an international system of professional recognition for public health nutritionists: a feasibility study within the European Union. Public Health Nutrition. 2012;15(11):2005–2011. doi:10.1017/S1368980012000547

- Burdick W, Dhillon I. Ensuring quality of health workforce education and practice: strengthening roles of accreditation and regulatory systems. Human Resour Health. 2020;18(1):71. doi:10.1186/s12960-020-00517-4

- RecoNow. The Higher Education System in Palestine: National Report. Knowledge of recognition procedures in ENPI South Countries; 2016.

- PMC. Palestine Medical Council E-Learning and Accreditation System (PMC-EAS) Ramallah. Palestine: Palestinian Medical Council; 2019 Available from: https://www.pmc.ps/en/category-42/1334.html. Accessed August 1, 2024.