Abstract

Objective

The goal of this scoping review was to summarize the current literature identifying barriers and opportunities that facilitate adoption of e-health technology by physicians.

Design

Scoping review.

Setting

MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO databases as provided by Ovid were searched from their inception to July 2015. Studies captured by the search strategy were screened by two reviewers and included if the focus was on barriers and facilitators of e-health technology adoption by physicians.

Results

Full-text screening yielded 74 studies to be included in the scoping review. Within those studies, eleven themes were identified, including cost and liability issues, unwillingness to use e-health technology, and training and support.

Conclusion

Cost and liability issues, unwillingness to use e-health technology, and training and support were the most frequently mentioned barriers and facilitators to the adoption of e-health technology. Government-level payment incentives and privacy laws to protect health information may be the key to overcome cost and liability issues. The adoption of e-health technology may be facilitated by tailoring to the individual physician’s knowledge of the e-health technology and the use of follow-up sessions for physicians and on-site experts to support their use of the e-health technology. To ensure the effective uptake of e-health technologies, physician perspectives need to be considered in creating an environment that enables the adoption of e-health strategies.

Background

Health care systems face challenges delivering care across the continuum, specifically for the aging population with complex chronic conditions. Health information technology, particularly information and communication technology, presents a solution to address these challengesCitation1,Citation2 by providing ways to increase health service effectiveness and improve patient outcomes and health care delivery.Citation1,Citation2 For instance, electronic medical records (EMRs) have been shown to significantly reduce the occurrence of medication errors;Citation3 prescription errors and compliance by patients to medication regimes have been shown to improve with electronic prescribing.Citation4 In addition, point-of-care decision support tools enable health care providers to receive alerts for contraindicated medications instantaneously.Citation5 Furthermore, there is evidence that e-health systems have resulted in fewer hospital visits and cost savings to the health care system.Citation6 In particular, this communication tool was used by elderly people at home to receive advice from nurses, saving visits to the clinics (emergency and elective).

This positive evidence has supported the implementation of e-health technology across the globe, ensuring the commitment of governments such as the US and a number of countries in Europe to allocate a significant amount of resources to promote e-health technology. Examples include the implementation of EMR by 29% and 17% of primary care physicians in the European Union and the US, respectivelyCitation7 and $19 billion committed to the promotion of health care information technology by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act 2009.Citation8

However, despite the high investment on e-health technology by health care systems, the evidence of the effects of e-health benefits is still very poor. In some instances, the lack of systems structures (eg, integration of e-health systems) presents a barrier to the adoption of the new technology, while in other cases it can be harmful. For instance, recent studies developed and implemented an e-health communication tool to transfer patient summary of stay in hospital from acute to community-based physicians, assessing the experiences of both group of physicians.Citation9,Citation10 This study revealed that although the e-health communication tool was well received, the adoption of the new technology was very slow.Citation10

Furthermore, an example of the latter is the study conducted by Lupianez-Villanueva et alCitation11 who argue that there can be a disconnect between the proposed benefits and the actual outcomes of e-health technology. The Web 2.0 described in their study has been suggested as a way to improve social interaction in health care; however, it did not foster communication between patients and doctors.Citation11 This study indicates that the effects of e-health technology are not always positive and the benefits of their use are not always straightforward.

Clearly, there are differences in the effects of e-health technologies that depend on the type and situation of the technology; however, implementation of such technologies continues, sometimes with support from government in both deployment and promotion.

Nowadays, despite studies indicating the benefits from certain kinds of e-health technology and the interest from policy makers to implement the innovative technology, the uptake and adoption of e-health technologies has not always been consistent within health care practice, and adoption of these technologies has lagged behind.Citation12 Physicians’ acceptance of e-health technology is critical, and thus it is important to identify influences that lag the uptake in order to overcome it.

The objective of this scoping review is to identify and summarize the current literature identifying barriers and opportunities that facilitate and hinder the adoption and implementation processes of e-health technology by physicians.

Methods

To identify relevant references the following databases were searched electronically since their inception to July 24, 2015: Ovid MEDLINE, including in-process and other nonindexed citations; Ovid EMBASE; and Ovid PsycINFO. In an attempt to track gray literature, Google Scholar was used. The search strategy used for searching MEDLINE is provided as an example (Supplementary materials). It was modified according to the indexing systems of other databases. As shown in the supplementary materials, selected subject headings and keywords were searched on physicians, e-health technology, and physicians’ attitudes. No language restrictions or publication date range limits were applied. In addition, we also scanned reference lists from retrieved articles and journals to identify additional studies for this review. The scoping review methodology will be guided by recommendations published in Arskey and O’Malley’s methodological framework.Citation13

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion

Studies that focus on barriers and opportunities of e-health technology adoption and implementation by physicians were included in this scoping review.

Exclusion

Studies were excluded if they met the following criteria:

Studies in which barriers or opportunities for the adoptions of e-health technology were not described

Barriers or opportunities for adoption of e-health technology were described for nonphysician health care providers

Overview of the literature for the purpose of theory building

An overview of the literature for the purpose of an editorial

Editorials

This scoping review focused on nonrandomized studies due to the nature of the objectives of the study. Nonrandomized studies include nonrandomized controlled trials, controlled before-and-after studies, prospective cohort studies, retrospective cohort studies, case–control studies, and cross-sectional studies.

Study selection

Two investigators independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all applicable studies from the initial search and identified those that met the inclusion criteria. Studies that were not relevant and nonprimary data were excluded in the screening of titles and abstracts. Discrepancy was resolved through discussion and consensus. Kappa statistics were used to assess the level of agreement between the two reviewers.

Data extraction and analysis

Textual descriptions and data tables were used to organize information concerning extracted data by the two reviewers (authors CD and AR). The results were synthesized through a detailed description of characteristics and findings of the included studies. Tables were used to present counts and percentages, details regarding study design, intervention, duration of intervention, outcome of interest, results, and study quality. A narrative synthesis was conducted to provide an overall picture of the available information. Within this narrative synthesis, patterns or “themes” were identified and aggregated together. This process involved the authors familiarizing themselves with the data, generating codes, identifying themes within the codes, and naming the themes.

Results

Identification and inclusion of studies

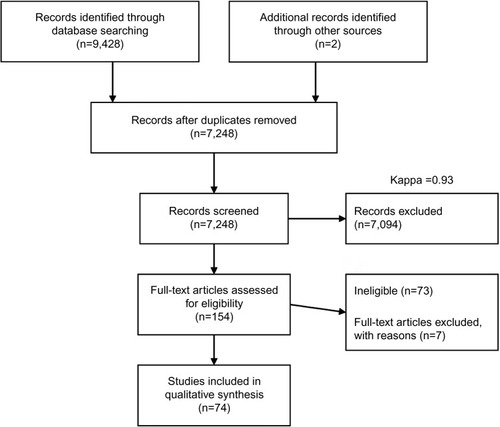

The search strategy yielded a total of 9,428 articles as shown in .Citation14 With the screening of titles and abstracts, a kappa score of 0.93 was obtained and 154 articles remained to be reviewed in full detail. Following full-text review, 80 articles were excluded mainly for including barriers or opportunities to adoption of e-health technology for nonphysician health care providers and lacked barriers or opportunities for implementation of e-health technology as a main objective in the study. Seventy-four studies were included in this scoping review.

More than half of the studies (62.2%) included originated from North America (). The included studies used quantitative methods (54.1%) to determine barriers and facilitators contributing to the adoption of e-health technology ( and supplementary materials). Qualitative studies (32.4%) that were included provided structured and in-depth information regarding barriers and facilitators contributing to the adoption of e-health technology ( and supplementary materials). These studies utilized a number of designs including semi-structured interviews with physicians either in person or by phone and focus groups. The remainders of the studies were systematic reviews, mixed methods, and literature reviews. EMRs or electronic health records and telemedicine were studied in 47.3% and 13.5% of the included studies, respectively, and they were the most common types of e-health technologies assessed ( and supplementary materials).

Table 1 General characteristics of studies included in the review (n=74)

Outcomes assessed

The outcomes we examined from studies included in the review were the satisfaction level of physicians, impact of the new e-health technology on the relationship between professionals and respective patients, impact of the new e-health technology on the relationship between health care professionals, the level of skill required for the implementation of the new e-health technology, and the level of complexity of the new e-health technology.

Barriers and perceived facilitators

Barriers and facilitators to the adoption and implementation of e-health technologies from the 74 studies were sorted into common theme groups identified in the review.

Barriers

Design and technical concerns

Two subthemes were identified:

Lack of harmonization of e-health systems: A notable barrier to the adoption of e-health technology is the development of a system that is not compatible with existing systems, although system integration was considered to be very important to physicians.Citation15–Citation27

Usability issues: Physicians expressed the importance of developing e-health technology that is simple to use, with physicians using terms such as “user friendly” and “intuitive”.Citation15,Citation17,Citation20,Citation22,Citation23,Citation25,Citation28–Citation37 As one physician stated, “lots of features were available in the system, but it was always very difficult for me to find the features at the time when I needed them”.Citation27

Privacy and security concerns

ConfidentialityCitation15,Citation32,Citation38–Citation40 and privacyCitation19,Citation27,Citation32,Citation39,Citation41,Citation42 were reported as important concerns for physicians. As one physician pointed out, “some patients do not want to share their medical records because of the sensitive health data such as HIV test information”.Citation27 Physicians were concerned that the integration of e-health technology into current systems may compromise the confidentiality of health data.Citation15,Citation28 Existence of health care professional codes of conduct and informed consent from patients were listed as protective factors against confidentiality concerns.Citation15 Privacy concerns were centered on the fear that e-health technology may attract “hackers”.Citation32 Furthermore, physicians feared that e-health technology would be implemented imperfectly, allowing for security vulnerabilities.Citation32

Cost and liability issues

Physicians were also less willing to use e-health technology if rules surrounding reimbursement15,Citation23–Citation25,Citation27,Citation38–Citation41,Citation43–Citation55–Citation57 and liability were not determined in advance.Citation38,Citation43,Citation48 Physicians wondered how the expenses associated with maintaining e-health devices would be covered.Citation20,Citation40,Citation43,Citation44,Citation49,Citation50,Citation53,Citation54,Citation58 It was expressed that financial incentives would encourage physicians to adopt e-health systems and take on additional workload.Citation15 Some physicians, on the other hand, were very concerned with medical malpractice suits that may arise from deferring tests based on health information obtained from telemedicine.Citation16,Citation47,Citation53

Productivity

Physicians expressed concern over loss of productivity during the implementation process of e-health technology.Citation41,Citation45,Citation46 Post implementation, physicians were also concerned that productivity would be decreased with increased work of documentation and difficulties associated with using systems or devices that may not be user-friendly.Citation46,Citation49,Citation50,Citation54,Citation59,Citation60

Patient and physician interaction

Physicians stated concerns regarding the loss of contact between patient and the physician with the utilization of telemedicine device.Citation19,Citation23,Citation26,Citation27,Citation30,Citation43,Citation53,Citation57,Citation58 As one physician summarized, “I found it (e-health technology) quite fiddly and complicated and spent too much time in the consult with the computer rather than talking to the family”. However, if it was perceived that patients liked their physicians utilizing e-health technology, physicians were more likely to use e-health technology.Citation61 Other studies found that e-health technologies are likely to integrate delivery of health care allowing for self-management and mutual respect between the patient and physician.Citation15

Lack of time and workload

Studies have cited lack of time and workload experienced by physicians as other key barriers to the implementation of e-health technology.Citation19,Citation24,Citation32,Citation33,Citation38,Citation41,Citation42,Citation48,Citation51,Citation55,Citation58,Citation62–Citation64 More specifically, there were concerns expressed about the time required to implement and acquire the necessary skills to learn e-health technology. Some believed that e-health technology would demand time away from their clinical tasks. Therefore, some physicians attributed successful use of e-health technology to personal initiative.Citation31 Others found that smaller practices were less likely to adopt e-health technology due to the lack of support.Citation58 Another common concern was the volume of information generated by e-health technology. Physicians were concerned that they would not be able to effectively synthesize and address the large volumes of data.Citation15,Citation43 Other physicians were concerned that e-health technology might shift workload onto them.Citation18,Citation32,Citation60

Threatened clinical autonomy

Some physicians expressed thoughts that certain physicians would not be willing to change their practice patterns and use telemedicine devices.Citation16,Citation28,Citation38–Citation41,Citation43,Citation47,Citation65–Citation68 This may be due to the physicians’ desire to form their own clinical decisions without the “bias” that may be introduced by e-health technology.Citation16 Or, in some cases, some physicians simply feared change.Citation66 Other studies have shown that older physicians are less likely to adopt and utilize EMR systems.Citation58,Citation68 Other physicians were concerned that the information generated by e-health technology, specifically health information exchange, may “flaw the logical process of their decision making” by formulating a diagnosis prior to assessing the patient.Citation16 Unwillingness to adopt e-health technology was the major reason behind the perceived threatened clinical autonomy.Citation21,Citation23,Citation38,Citation65,Citation66,Citation69 Other physicians stated that learning required time and effort, which could not be avoided through design.Citation31 These physicians believed that one needs to adjust their behavior accordingly to fit the design of the e-health technology.Citation31

Facilitators

Pre-analysis of data

Given the potential for e-health technology to generate large volumes of data, physicians would like a “pre-analysis” of the generated information.Citation15,Citation38,Citation43,Citation56 Pre-analysis of data would include screening and processing of raw data either electronically or by hand.Citation15,Citation38,Citation43 Physicians expressed that they would like to see an analysis of data rather than raw data.Citation43 They would like to receive an alert after a certain number of reports are generated on the patient instead of continuously receiving alerts following every report of patient symptoms or treatment outcomes from pre-analysis in order to reduce alert fatigue.Citation15,Citation43 The generated data should also assist physicians in detecting adverse events, where possible.Citation43

Proof of utility

Physicians stated that they would be more likely to utilize e-health technology if research supports its utility,Citation17,Citation20,Citation27,Citation30,Citation42,Citation54,Citation55,Citation57 mainly in reducing adverse events such as medication errors and drug interactions.Citation43,Citation47 One physician stated that the ability to trial the software prior to purchasing it influenced their decision to adopt the EMR system.Citation36 As another physician stated “it will be useful if the EMR system allows my assistants to print medication labels directly off the machine and attach them to the drug bags and bottles as this can help reduce clerical and labeling errors caused by handwriting”.Citation27 Also physicians with previous experience in using e-health technology had more of a positive attitude toward e-health technology and were more positive about integrating telehealth into their practice.Citation15,Citation21,Citation27,Citation28,Citation50,Citation61,Citation70,Citation71

Training and support

Training and support was an important facilitator to the adoption of e-health technology.Citation15–Citation18,Citation21,Citation27,Citation31,Citation38,Citation42,Citation46,Citation49,Citation50,Citation52–Citation54,Citation62,Citation64,Citation65,Citation70,Citation72,Citation73 As one physician stated, “training in technical skills should be provided to my assistants in order for them to become capable of using the system, but it will be extra work for me if I need to do the training myself ”.Citation27 Training would need to be tailored to the individual physician’s knowledge of the e-health technology with “on-site experts” who are able to provide first-line support.Citation15,Citation24,Citation31,Citation62 In addition, follow-up training sessions were also considered important to the adoption of telemedicine.Citation15,Citation16,Citation24,Citation31,Citation65,Citation70 Some physicians mentioned that having organizational leadership or a champion encouraged the adoption of e-health technology.Citation73 Other physicians preferred one-on-one, on-demand support during real-life situations.Citation31 In addition, lack of information technology (IT) skills can be seen as a barrier to the utilization of e-health technology.Citation24,Citation30,Citation31,Citation34,Citation41,Citation51,Citation52,Citation62,Citation65,Citation67,Citation71 As one physician said, “… I cannot type and talk and listen to patients at the same time … so I may not use the system”. Furthermore, those with innovative office staff were more likely to adopt e-health technology in their respective practices.Citation74,Citation75,Citation76

Ownership and size of practice

Physicians who were partial or full owners of their practice were less likely to adopt e-health technology.Citation50,Citation73,Citation75 This may be due to ownership being associated with higher levels of responsibility for day-to-day operations.Citation75 Furthermore, with increasing size of practice, physicians were less likely to adopt e-health technology.Citation77 Smaller and lower income practices were found to be less likely to use EMRs.Citation78 Another study found that independent practices are less likely to adopt e-health technology when compared to group practices.Citation40,Citation49,Citation51,Citation71,Citation73,Citation76 The literature presents an interesting contradiction where ownership and size of practice can be either a facilitator or a barrier to adoption of e-health technology. Ownership and size of practice as a barrier or facilitator seemed to depend on the type of e-health technology; EMRs, in particular, were more likely to be used in a larger practice than solo, whereas other types of e-health technology such as email communication with patients were the opposite.Citation51,Citation71,Citation74,Citation78

Discussion and conclusion

This scoping review identifies a number of barriers and facilitators to the adoption of e-health technology by physicians. Among these themes, threatened clinical autonomy, cost and liability issues, and training and support were the most cited. Boonstra and Broekhuis,Citation79 Castillo et al,Citation80 Gagnon et al,Citation81 and Goldstein et alCitation82 support these findings. They found that the most cited barriers to EMR adoption as financial, lack of time, and technical barriers.

Boonstra and BroekhuisCitation79 identified these most cited barriers as “primary” barriers, given that such barriers are first to arise with the adoption process of EMR. We also found other factors that need to be addressed such as motivation to adopt e-health technology, patient–physician interaction, training and support, system factors, and threatened autonomy.

One of the main themes that became apparent was the threatened clinical autonomy. This may be due to multiple factors such as the physicians’ desire to autonomously form their own clinical decisions without information provided by e-health technology,Citation16 fear of change,Citation66 age,Citation58,Citation68 unwillingness to adopt,Citation21,Citation23,Citation38,Citation65,Citation66,Citation69 and limitation in time and effort.Citation31 Walter and LopezCitation69 defined professional autonomy as “professionals” having control over the conditions, processes, procedures, or content of their work according to their own collective and, ultimately, individual judgment in the application of their profession’s body of knowledge and expertise professional privacy. They found that threatened professional autonomy negatively affected perceived usefulness and the intention to use e-health technology.Citation69

The second main theme that arose was cost and liability issues associated with the adoption of e-health technology by physicians. Concerns regarding reimbursement were the most cited within this theme. Physicians were less willing to utilize e-health technology with no reimbursement initiatives present. In order to facilitate the adoption of EMR systems with “meaningful use”, The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 allocated ~$19 billion toward incentive payments through Medicare and Medicaid. It is estimated that by 2015, there would have been acceleration in the adoption of EMRs due to the financial incentive payments as well as Medicare penalty associated with the failure to implement EMR.

The third main theme that arose in this study was the barriers surrounding training and support. Poor services from the vendor such as poor training and support for problems associated with the e-health technology and poor follow-up are barriers to the adoption of such devices. This is further complicated given that physicians are not technical experts and the systems are inherently complicated. In order to further facilitate the adoption of e-health technology, physicians need the technology to be tailored to the individuals’ knowledge of the e-health technology. Furthermore, “on-site experts” who are able to provide first-line support were highly encouraged. Lastly, follow-up sessions were considered an important factor contributing to the adoption of e-health technology.

Addressing barriers to the implementation of e-health technology is a complex process that requires support from health services authority, insurance companies, vendors, patients, and physicians. The findings of this scoping review suggest that not all barriers are present in all practices. It is important for policy makers and hospital or practice managers to understand the specific barriers that challenge the practicing physicians and design appropriate interventions to address barriers and promote facilitating factors. This may be achieved through running in-depth interviews with the users, in this case physicians, to learn what specific barriers challenge the particular practice. The acquisition of this knowledge will allow for the development of a customized implementation plan.

It is important to note that some barriers to the adoption of e-health technology are not within the control of implementers. Such barriers include high cost associated with the adoption and maintenance of e-health technology. In order to overcome this barrier, government incentives may be required.Citation83 Privacy and security concerns are also barriers that are beyond the control of implementers. In order to overcome this barrier, government action may be required to establish and implement national privacy laws.Citation83 Many countries have developed new laws and regulations to address privacy and security concerns. For instance, in the US, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule protects personal health information.

It is worthy to note that some countries have implemented national initiatives to overcome barriers associated with EMRs. In Canada, the Canada Health Infoway is an initiative that exists to facilitate the adoption of EMRs across the country by addressing technical and financial barriers. In the US, the Hitech Act provides incentive payments for the adoption and use of EMRs in order to address financial barriers. In Australia, HealthConnect is a national initiative to ensure that health information is securely exchanged.

This study identified current barriers and facilitators to the adoption of e-health technology by physicians and adds to the body of literature surrounding barriers and facilitators to the adoption of e-health technology. As e-health technology becomes a priority in health care and more technologies and studies evaluating the use of these technologies emerge, it is important to update the current barriers and facilitators to their adoption and implementation. The systematic reviews included in this scoping review illustrate the need for updated information and a broader focus as most focused on EMRs and all were done in or before 2014. This scoping review also discusses implications of broad- and fine-scale barriers and facilitators, such as organizational factors, and physician characteristics, such as productivity. The identification of such barriers and facilitators is important because it allows for the implementation of a targeted strategy. Implementers need to consider physician perspectives and gain their support by addressing barriers in order to create an environment where e-health technology is adopted.

This scoping review had some limitations. Although it was attempted to develop a comprehensive search strategy, electronic health technology is a very broad topic, and it is possible some relevant studies were missed. Second, other health care professionals and the patient’s perspectives were not considered although both are stakeholders in the adoption of e-health technology. Thus, articles that address technologies that are more appropriate to physicians and their patients may be emphasized here, as factors specific to other health care providers perspectives were not included. Alternately, there may be barriers that are exclusive to other health care professionals or patients that significantly hinder the adoption of such technology that were missed. Other studies have been conducted that capture the perspectives of these stakeholders that were not included in this study.

Future implications

The findings of this scoping review indicate that physicians are a diverse group of individuals faced with differing barriers and facilitators that exist within different subspecialties. Therefore, it is crucial to consider specific concerns of these subspecialties within the health care providers’ umbrella when implementing new e-health technologies and encouraging use of existing e-health technologies.

Future projects should consider the tensions around the adoption and develop programs to address physician-limited resources and system barriers. For instance, providing financial payback for achieving quality improvement though IT use may increase the adoption of e-health technology. Reimbursements may be provided for publishing performance reports and the use of specific IT applications. For instance, in 2003, California initiated the “pay-for-performance” program where health plans measure and reward performance, patient satisfaction, and IT use in ambulatory care. Performance incentive programs may reward performance based on multiple clinical indices and encourage users to globally use e-health technology to achieve such gains. Alternatively, performance incentive programs may selectively promote specific IT indices.

Micromanaging clinical change should be avoided. Mandating “pop-up” reminder may be complementary for some practices and intrusive in others. Indiscriminate deadlines for full EMR use should also be avoided. Full EMR use should be achieved via stepwise approach. Basic EMR use such as prescription ordering may be expected initially. Only when basic EMR use is achieved, should incentive requirement for more advanced EMR capabilities such as decision support be required. Questions remain about the design of performance incentive programs; however, the adoption of pay-for-performance programs could positively impact the uptake of e-health technology in clinical practice.

Conclusion

Our results illustrate that there is often great uncertainty about the costs, implementation, and consequence of e-health technology. One avenue that could mitigate this uncertainty is the development of comprehensive product comparisons of EMRs. Government funding could fund product comparisons of e-health technology and research identifying full range of financial, time, and quality outcomes of EMR-using practices. Such comparison projects will allow physicians to fully visualize the impact that the adoption of e-health technology may have on their clinical practice.

Author contributions

Chloe de Grood and Aida Raissi screened titles, abstracts, and full-text articles to be included in the review; both drafted and edited the final manuscript. Yoojin Kwon conducted and developed the search strategy and also contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. Maria Jose Santana developed the concept of the project, contributed to the search strategy, supported the article screening process, and also drafted and edited the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Susan Powelson, Librarian, Taylor Family Digital Library, University of Calgary, for her support and the reviewers for their critical feedback. This work was supported by Ward of the 21st Century Research and Innovation Center (www.w21c.org), University of Calgary.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PringleMThe computer-based record for health care: an essential technology for health careBr J Gen Pract1992359262

- BatesDWEbellMGotliebEZappJMullinsHCA proposal for electronic medical records in US primary careJ Am Med Inform Assoc200310111012509352

- BatesDWCohenMLeapeLLOverhageJMShabotMMSheridanTReducing the frequency of errors in medicine using information technologyJ Am Med Inform Assoc20018429930811418536

- PorterfieldAEngelbertKCoustasseAElectronic prescribing: improving the efficiency and accuracy of prescribing in the ambulatory care settingPerspect Health Inf Manag201411Spring1g

- KupermanGJBobbAPayneTHMedication-related clinical support in computerized provider order entry systems: a reviewJ Am Med Inform Assoc2007141294017068355

- AkematsuYTsujiMAn empirical approach to estimating the effect of e-health on medical expenditureJ Telemed Telecare201016416917120511565

- AndersonJGBalasEAComputerization of primary care in the United StatesInt J Med Inform20063123

- American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (2009)US Government Publishing Office Available from: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-111hres168rh/pdf/BILLS-111hres168rhAccessed September 12, 2015

- SantanaMJHolroyd-LeducJFlemonsWWThe seamless transfer of care: a pilot study assessing the usability of an electronic transfer of care toolAm J Med Qual201429647648324052455

- de GroodCEsoKSantanaMSPhysicians’ experience adopting the electronic transfer of care communication tool: barriers and opportunitiesJ Multidiscip Healthc201582125609977

- Lupianez-VillanuevaFMayerMATorrentJOpportunities and challenges of Web 2.0 within the health care systems: an empirical explorationInform Health Soc Care200934311712619670002

- AjamiSKetabiSSaghaeian-NejadSRequirements and areas associated with readiness assessment of electronic health records implementationJ Health Admin2011147178

- ArkseyHO’MalleyLScoping studies: towards a methodological frameworkInt J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract2005811932

- MoherDLiberatiATetzlaffJAltmanDGThe PRISMA GroupPreferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statementPLoS Med200966e100009719621072

- AjamiSBagheri-TadiTBarriers for adopting Electronic Health Records (EHRs) by physiciansActa Inform Med201321212913424058254

- DavidsonESimpsonCRDemirisGSheikhAMcKinstryBIntegrating telehealth care-generated data with the family practice electronic medical record: qualitative exploration of the views of primary care staffJ Med Res201322e29

- ThornSACarterMABaileyJEEmergency physicians’ perspectives on their use of health information exchangeAnnu Emerg Med2014633329337

- PutzerGJParkYAre physicians likely to adopt emerging mobile technologies? Attitudes and innovation factors affecting smartphone use in the Southeastern United StatesPerspect Health Inf Manag20129Spring1b

- StrausSGChenAHYeeHJrKushelMBBellDSImplementation of an electronic referral system for outpatient specialty careAMIA Annu Symp Proc201120111337134622195195

- YauGLWilliamsASBrownJBFamily physicians’ perspectives on personal health records: qualitative studyCan Fam Physician201155e178e18421642732

- SteinschadenTPeterssonGAstrandBPhysicians’ attitudes towards eprescribing: a comparative web survey in Austria and SwedenInform Prim Care200917424124820359402

- MortonEWiedenbeckSA framework for predicting EHR adoption attitudes: a physician surveyPerspect Health Inf Manag20096Fall1a19169377

- PizziLTSuhDCBaroneJNashDBFactors related to physicians’ adoption of electronic prescribing: results from a national surveyAm J Med Qual2005201223215782752

- VishwanathAScamurraSBarriers to the adoption of electronic health records: using concept mapping to develop a comprehensive empirical modelHealth Informatics J200713211913417510224

- GreiverMBarnsleyJGlazierRHMoineddinRHarveyBJImplementation of electronic medical records: theory-informed qualitative studyCan Fam Physician20115710e390e39721998247

- MuslinISVardamanJMCornellPTFostering acceptance of computerized physician order entry: insights from an implementation studyHealth Care Manag2014332165171

- DikomitisLGreenTMacleodUEmbedding electronic decision-support tools for suspected cancer in primary care: a qualitative study of GPs’ experiencesPrim Health Care Res Develop2015166548555

- BrooksETurveyCAugusterferEProvider barriers to telemental health: obstacles overcome, obstacles remainingTelemed J E Health201319643343723590176

- IqbalUHoCHLiYCNguyenPAJianWSWenHCThe relationship between usage intention and adoption of electronic health records at primary care clinicsComput Methods Programs Biomed2013112373173724091088

- ChenRHsiaoJAn investigation on physicians’ acceptance of hospital information systems: a case studyInt J Med Inform2012811281082022652011

- DunnebeilSSunyaevABlohmILeimeisterJMKrcmarHDeterminants of physicians’ technology acceptance for e-health in ambulatory careInt J Med Inform2012811174676022397989

- VedelILapointeLLussierMHealthcare professionals’ adoption and use of a clinical information system (CIS) in primary care: insights from the Da Vinci studyInt J Med Inform2012812738722192460

- HoldenRWhat stands in the way of technology-mediated patient safety improvements?: a study of facilitators and barriers to physicians’ use of electronic health recordsJ Patient Saf20117419320322064624

- HacklWOHoerbstAAmmenwerthEWhy the hell do we need electronic health records? EHR acceptance among physicians in private practice in Austria: a qualitative studyMethods Inf Med2011501536121057716

- HierDRothschileALeMaistreAKeelerJDiffering faculty and housestaff acceptance of an electronic health recordInt J Med Inform2005747–865766216043088

- PernaGSoul road: one solo doc’s extensive EMR journey implementing an EMR is a long process fraught with obstacles, especially for a solo practitionerHealthc Inform2013313363824941605

- RussALZillichAJMcManusMSDoebbelingBNSaleemJJA human factors investigation of medication alerts: barriers to prescriber decision-making and clinical workflowAMIA Annu Symp Proc2009200954855220351915

- OlenikKLehrBCounteracting brain drain of health professionals from rural areas via teleconsultation: analysis of the barriers and success factors of teleconsultationJ Public Health201321357364

- BradfordNKYoungJArmfieldNRHerbertASmithACHome telehealth and paediatric palliative care: clinician perceptions of what is stopping us?BMC Palliat Care2014132924963287

- SimonSKaushalRClearyPPhysicians and electronic health records: a statewide surveyArch Intern Med2007167550751217353500

- ValdesIKibbeDTollesonGKunikMEPetersenLABarriers to proliferation of electronic medical recordsInform Prim Care20041213915140347

- BadranHPluyePGradRAdvantages and disadvantages of educational email alerts for family physicians: viewpointJ Med Internet Res2015172e4925803184

- LevineMRichardsonJGranieriEReidMCNovel telemedicine technologies in geriatric chronic non-cancer pain: primary care providers’ perspectivesPain Med201415220621324341423

- JariwalaKSHolmesERBanahanBF3rdMcCaffreyDJ3rdFactors that physicians find encouraging and discouraging about electronic prescribing: a quantitative studyJ Am Med Inform Assoc201320e1e39e4323355460

- LeuMO’ConnorKMarhsallRPriceDTKleinJDPediatricians’ use of health information technology: a national surveyPediatrics20121306e1441e144623166335

- YanXLiuTGruberLHeMCongdonNAttitudes of physicians, patients, and village health workers toward glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy in rural China: a focus group studyArch Ophthalmol2012130676177022801838

- RogoveHJMcArthurDDemaerschalkBMVespaPMBarriers to telemedicine: survey of current users in acute care unitsTelemed J E Health2012181485322082107

- MoskowtizAChanYBrunsJLevineSREmergency physician and stroke specialist beliefs and expectations regarding telestrokeStroke201041480580920167910

- StreamGTrends in adoption of electronic health records by family physicians in Washington StateInform Prim Care200917314515220074426

- KaushalRBatesDJenterCImminent adopters of electronic health records in ambulatory careInform Prim Care200917171519490768

- MenachemiNBarriers to ambulatory EHR: who are ‘imminent adopters’ and how do they differ from other physicians?Inform Prim Care200614210110817059699

- LeungGMYuPLWongIOJohnstonJMTinKYIncentives and barriers that influence clinical computerization in Hong Kong: a population-based physician surveyJ Am Med Inform Assoc200310220121212595409

- KaneJMorkenJBoulgerJCrouseBBergeronDRural Minnesota family physicians’ attitudes toward telemedicineMinn Med199578319237739473

- JamoomEWPatelVFurukawaMFKingJEHR adopters vs. non-adopters: impacts of, barriers to, and federal initiatives for EHR adoptionHealthc (Amst)201421333926250087

- Villalba-MoraECasasILupiañez-VillanuevaFMaghirosIAdoption of health information technologies by physicians for clinical practice: the Andalusian caseInt J Med Inform201584747748525823578

- DavisMMCurreyJMHowkSA qualitative study of rural primary care clinician views on remote monitoring technologiesJ Rural Health2013301697824383486

- SinclairCHollowayKRileyGAuretKOnline mental health resources in rural Australia: clinician perceptions of acceptabilityJ Med Internet Res2013159199208

- OrCWongKTongESekAPrivate primary care physicians’ perspectives on factors affecting the adoption of electronic medical records: a qualitative pre-implementation studyWork201448452953824346272

- LarsenFGjerdrumEObstfelderALundvollLImplementing telemedicine services in northern Norway: barriers and facilitatorsJ Telemed Telecare20039suppl 1S17S1812952708

- SinghDSpiersSBeasleyBCharacteristics of CPOE systems and obstacles to implementation that physicians believe will affect adoptionSouth Med J2011104641842121886031

- SchectmanJMSchorlingJBNadkarniMMVossJDDeterminants of physician use of an ambulatory prescription expert systemInt J Med Inform200574971171715985385

- TerryALGilesGBrownJBThindAStewartMAdoption of electronic medical records in family practice: the providers’ perspectiveFam Med200941750851219582637

- MeadeBBuckleyDBolandMWhat factors affect the use of electronic patient records by Irish GPs?Int J Med Inform200978855155819375381

- D’AlessandroDMD’AlessandroMPGalvinJRKashJBWakefieldDSErkonenWEBarriers to rural physician use of a digital health sciences libraryBull Med Libr Assoc19988645835939803304

- HainsIWardRPearsonSImplementing a web-based oncology protocol system in Australia: evaluation of the first 3 years of operationIntern Med J2012421576420546055

- CampbellJHarrisKHodgeRIntroducing telemedicine technology to rural physicians and settingsJ Fam Pract200150541942411350706

- AraújoMTPaivaTJesuinoJCMagalhãesMGeneral practitioners and neurotelemedicineStud Health Technol Inform200078456711151607

- AbdekhodaMAhmadiMGohariMNoruziAThe effects of organizational contextual factors on physicians’ attitude toward adoption of electronic medical recordsJ Biomed Inform20155317417925445481

- WalterZLopezMSPhysician acceptance of information technologies: role of perceived threat to professional autonomyDecis Support Syst200846206215

- DevineEWilliamsEMartinDPrescriber and staff perceptions of an electronic prescribing system in primary care: a qualitative assessmentBMC Med Inform Decis Mak2010107221087524

- MenachemiNBrooksREHR and other IT adoption among physicians: results of a large-scale statewide analysisJ Healthc Inf Manag2006203798716903665

- CheungCSTongELCheungNTFactors associated with adoption of the electronic health record system among primary care physiciansJMIR Med Inform201311e125599989

- BrambleJGaltKSiracuseMThe relationship between physician practice characteristics and physician adoption of electronic health recordsHealth Care Manage Rev2010351556420010013

- AnckerJSSinghMPThomasRPredictors of success for electronic health record implementation in small physician practicesAppl Clin Inform201341122423650484

- FleurantMKellRLoveJMassachusetts E-health project increased physicians’ ability to use registries, and signals progress toward better careHealth Aff (Millwood)20113071256126421734198

- KralewskiJEDowdBECole-AdeniyiTGansDMalakarLElsonBFactors influencing physician use of clinical electronic information technologies after adoption by their medical group practicesHealth Care Manage Rev200833436136718815501

- PevnickJAschSAdamsJAdoption and use of stand-alone electronic prescribing in a health plan-sponsored initiativeAm J Manag Care201016318218920225913

- MazzoliniCEHR holdouts: why some physicians refuse to plug inMed Econ201490224225265806

- BoonstraABroekhuisMBarriers to the acceptance of electronic medical records by physicians from systematic review to taxonomy and interventionsBMC Health Serv Res20101023120691097

- CastilloVMartinez-GarciaAPulidoJA knowledge-based taxonomy of critical factors for adopting electronic health record systems by physicians: a systematic literature reviewBMC Med Inform Decis Mak2010106020950458

- GagnonMDesmartisMLabrecqueMImplementation of an electronic medical record in family practice: a case studyInform Prim Care2010181314020429976

- GoldsteinDHPhelanRWilsonRBrief review: adoption of electronic medical records to enhance acute pain managementCan J Anaesth201461216417924233770

- AndersonJGSocial, ethical and legal barriers to E-healthInt J Med Inform2007765–648048317064955