Abstract

Background

Chronic illness is a risk factor for low self-esteem, and the research literature needs to include more studies of self-esteem and its development in chronic illness groups using longitudinal and comparative designs. The aim of this study was to explore the trajectories of self-esteem and of positive and negative affect in persons with morbid obesity and in persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Methods

Patient education course attendants in Norway having morbid obesity (n=139) or COPD (n=97) participated in the study. Data concerning self-esteem, positive and negative affect, and sociodemographic background were collected at the start and at the end of the patient education, with subsequent follow-ups at 3, 6, and 12 months. Data were analyzed using linear mixed models for repeated measures.

Results

Taking all measurements into account, our data revealed a statistically significant increase in self-esteem for participants with morbid obesity but not for those with COPD. There were no significant differences in levels of negative and positive affect between the two groups, and the time-trajectories were also similar. However, participants in both groups achieved lower levels of negative affect for all the successive measurement points.

Conclusion

An increase in self-esteem during the first year after the patient education course was observed for persons with morbid obesity, but not for persons with COPD. Initial higher levels of self-esteem in the participants with COPD may indicate that they are less troubled with low self-esteem than people with morbid obesity are. The pattern of reduced negative affect for both groups during follow-up is promising.

Introduction

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, introduced in 2001, conceptualizes health as resulting from the interaction between the illness, the environment, and the person.Citation1 In relation to states of chronic or long-standing illness, self-esteem and affect are relevant personal factors to consider. Affect relates to the person’s mood state: positive affect reflects the extent to which a person is enthusiastic, active, and alert, whereas negative affect reflects distress and aversive mood, like anger, disgust, or fear.Citation2 Self-esteem, on the other hand, refers to a global feeling of self-worth that stems from the positive and negative evaluations we hold about ourselves.Citation3 Chronic illness may negatively affect self-esteem, as the person may experience burdensome consequences of the illness, decreased coping with everyday life, or negative reactions from the environment.Citation4–Citation7 Moreover, self-esteem may decrease with increasing severity of illness, as previously suggested.Citation8 However, the relationship may be dynamic, as low self-esteem may also contribute to lifestyle behaviors that eventually cause illness.

Research has shown that higher self-esteem is associated with more positive affect in persons with chronic illnessCitation9 and that higher self-esteem may buffer against additional problems like depression, stress, and negative emotions.Citation9–Citation11 Given that low self-esteem is also a symptom of depression, some overlap between the constructs measured in these studies should be noted. Such conceptual overlaps indicate that the associations between self-esteem and other outcomes may potentially be confounded by depression. Higher self-esteem has been associated with higher participation levels in persons with spinal cord injury.Citation12 Conversely, lower self-esteem for persons with type 1 diabetes has been associated with long-term problems related to feelings about the illness, food, treatment, and social support.Citation13

Research results have also been relatively consistent in support of the idea that affects in general, both positive and negative, can play a role in the well-being of persons living with chronic illness. In a study of rheumatoid arthritis patients, Strand et alCitation14 found that positive affect reduced the extent of negative emotions in weeks with more pain. In a study using a sample of patients with different chronic illnesses, Juth et alCitation9 reported relationships between low self-esteem and more negative affect, less positive affect, and greater severity of stress and symptoms. Similarly, Simpson et alCitation11 reported relationships between self-esteem, positive affect, and emotional well-being in persons with Parkinson’s disease. In a study of persons with morbid obesity, Lerdal et alCitation15 found a relationship between higher self-esteem and higher health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in the physical health domain, but an inverse association between lower self-esteem and higher HRQoL in the mental health domain.

Importantly, morbid obesity and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) share the characteristic of being associated with unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, most notably physical inactivity and overeating (morbid obesity), and smoking (COPD). However, persons in the two illness groups are markedly dissimilar in terms of expected illness progression. Morbid obesity is considered a chronic illness but can be countered by various means. By increasing physical activity and by improving the diet, the person can reduce weight and promote his or her own health. In addition, medication and surgery are also commonly used. In contrast, persons with COPD have a progressive disease with poor prospects of being cured. Self-management strategies, including regular physical activity, improved diet, and cessation of smoking, are equally important for persons with COPD to learn and adopt so as to improve symptom management and reduce or delay exacerbations of illness.

Research suggests that self-esteem and affect may change over time in persons with morbid obesity and persons with COPD. Increased self-esteem and reduced negative affect have been found in persons with morbid obesity 6 months after receiving gastric bypass surgery.Citation16 Similarly, a study of persons with COPD showed increased self-esteem in the participants during the 4 week intervention, and self-esteem continued to increase during the first month after discharge.Citation5 The current state of knowledge, thus, indicates possible interrelationships between trajectories of self-esteem, affect, and well-being in persons with chronic illness. Such interrelationships may also be different for illness groups with different prospects of being cured, but no studies appear to have explored this question in detail.

There are limitations to the knowledge provided by previous studies of change in self-esteem and affect among persons with chronic illness. Follow-up periods have been relatively short, and thus, the robustness of change across a longer timeline is unknown. Moreover, previous research has not yet explored the patterns of change in self-esteem and affect. Lastly, comparative views on change in different illness groups are rare. In the current study, we address these shortcomings. Using a sample consisting of two different illness groups, we assess self-esteem and affect at five time points during the first year after a patient education course, allowing for a fine-grained analysis of the change patterns.

Purpose

The present study aimed to describe 1-year trajectories of self-esteem and of positive and negative affect in persons with morbid obesity and in persons with COPD.

Research questions

What are the trajectories of self-esteem and positive and negative affect in persons with morbid obesity and in persons with COPD?

Are sociodemographic variables (ie, age, sex, and work status) associated with changes in self-esteem and positive and negative affect in persons with morbid obesity and in persons with COPD?

Method

Study design

In this observational study, data related to self-esteem, positive and negative affect, and sociodemographic variables were included in a longitudinal investigation of persons with morbid obesity and persons with COPD who participated in patient education. The study is part of a prospective longitudinal study designed to explore changes in HRQoL in persons participating in patient education courses in Norway and to test 12 instruments regarding perception of illness and coping strategies with regard to their ability to detect change over time.

Sample and data collection

In Norway, morbid obesity and COPD are two chronic illness groups for which patient education courses are frequently provided. During 2009–2010, a convenience sample of participants was recruited among morbidly obese and COPD patients about to begin a patient education course. All patients were referred to the course by a physician. There were no exclusion criteria, and all course participants were invited to participate in the study. The inclusion of morbidly obese participants required the person to have a body mass index of 40 kg/m2 or greater,Citation17 as this was the target group for the patient education course. The inclusion of participants with COPD required the person to be classified with moderate-to-severe limitation of airflow, representing Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stages 2 and 3, respectively.Citation18 After receiving verbal and written information about the study, course attendants were invited to participate. Data were collected at five time points: before the course started, 2 weeks after the course, and at 3, 6, and 12 months after the course (ie, follow-up).

Those who consented completed the first set of questionnaires (baseline assessment) in a secluded room on-site on the first day of the course and returned it in a sealed envelope. For the following assessments, participants completed the questionnaires at home and returned them to the researchers by mail.

Patient education courses

For both illness groups, the patient education courses were comparable in their theoretical orientation, but their content, duration, and organization were chosen with a specific view to the health and lifestyle problems in each of the specific groups. For the participants with morbid obesity, the patient education courses lasted between 9 and 15 weeks, consisting of approximately 40 hours of education, small group discussions, and work with individualized action plans. Health care professionals in cooperation with previous course participants developed the content of the course. The approach was grounded in social cognitive behavior theory. It emphasized the participants’ work in uncovering hidden resources, strengthening self-concept and social skills, and raising consciousness of lifestyle choices. It covered major subjects including available treatments and their intended and unintended consequences, necessary lifestyle changes, and subsequent changes in mind and body.Citation15

The patient education courses for participants with COPD were based on the same principles as those already discussed, and the duration of educational sessions varied between 20 and 48 hours. However, these courses had a shorter duration of 3–5 weeks and had fewer group sessions. The combined educational course and subsequent treatment were assumed to help the participants with COPD improve their understanding of and coping with illness, promote a healthier lifestyle, and thereby improve their HRQoL.Citation19

Measures

Self-esteem

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) was used to assess participants’ global self-esteem.Citation20 Rosenberg proposes the attributes of a person with high self-esteem: “self-respect, considers himself a person of worth”. The original RSES consists of ten statements with responses ranked from 1 “strongly agree” to 4 “strongly disagree.” Our study used a Norwegian abbreviated four-item version (RSES-4). The four items were selected by linear regression analysis, and the resulting scale showed high correlation (r=0.95) with the full ten-item version.Citation21 The sum-score on the RSES-4 ranges between 4 and 16, with higher scores representing higher self-esteem. Cronbach’s α was 0.80 for this study, resembling that of another Norwegian study.Citation22

Affect

The Positive and Negative Affects Schedule (PANAS) was used to assess the participants’ affects.Citation2 The PANAS consists of 20 listed affects. Ten items are considered positive and ten are considered negative, thus resulting in two 10-item scales for positive and negative affect, respectively. The positive affects scale consisted of the following items: interested, strong, inspired, attentive, enthusiastic, proud, alert, lively, active, and determined. The negative affect items were: distressed, upset, nervous, scared, hostile, irritable, ashamed, jittery, afraid, and guilty. Respondents were asked to indicate to what degree they had experienced each of the listed affects during the last week, replicating the procedure from a recent Norwegian study.Citation14 Item scores range between 1 (“very slightly or not at all”) and 5 (“extremely”). The scores on positive and negative affect were calculated as the sum score of the ten items belonging to the respective scale, both scales ranging from 1–5. Cronbach’s α was 0.88 and 0.87 for the positive and the negative affect scales, respectively. At baseline, there was a weak, however statistically significant, negative correlation between the two scales (r=−0.33, P<0.01), and the correlation was even weaker and not statistically significant at the end of the follow-up (r=−0.16, ns).

Sociodemographic background

Data for age, sex, education, and employment status were collected. Participants’ formal level of education was dichotomized as 12 years of education or less (secondary school) versus more than 12 years education (university/college education).

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS for Windows version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).Citation23 Differences between illness groups at baseline were assessed by chi-square (χ2) test for categorical variables or by independent t-test for continuous variables. Linear mixed model (LMM) regression analyses were used to produce estimates of both random and fixed effects. To be included in the analysis, participants needed to have valid scores on the outcome variables on more than one time of measurement, but not necessarily all. LMM provides estimates using all of the available data, and no imputation of missing data is necessary. Thus, the LMM represents an improved method for handling missing data points. The models included age, sex, work status, time, illness group, and time × illness group (interaction term), as fixed effects. Individual differences at baseline were accounted for by a random intercept parameter. Due to unequal time intervals between the times of measurement, covariance was modeled as unstructured. Restricted maximum likelihood estimation was used to produce unbiased estimates of the model parameters. Overall effects were analyzed using F-tests. The results are presented as estimated means with 95% confidence intervals. Cohen’s d was employed as effect size (ES) related to group comparisons, and a similar method (dividing the LMM estimates with their respective standard errors) was used to produce ESs related to the outcome trajectories. Due to the exploratory nature of our study, we did not employ any correction for multiple testing. The level of significance was set at P<0.05, and all tests were two-sided.

Ethics

The Norwegian Research Ethics Committee and the Ombudsman of Oslo University Hospital approved of the study (REK S-08662c 2008/17575; NCT 01336725). Informed written consent was received from all participants.

Results

Sample characteristics

Out of a total number of 312 course attendants, 242 (77.6%) consented to participate. Following the LMM statistical analysis procedure, six of the participants (three in each of the illness groups) were excluded due to not having valid scores on more than one time of measurement. The sample characteristics at baseline are described in . The participants with morbid obesity were younger, had a larger proportion of females, and were more often in paid work than their counterparts with COPD. The participants with COPD had a higher level of self-esteem, and a lower level of negative affect, compared to the participants with morbid obesity. There were no statistically significant group differences regarding positive affect.

Table 1 Characteristics of the sample at baseline (N=236)

Self-esteem

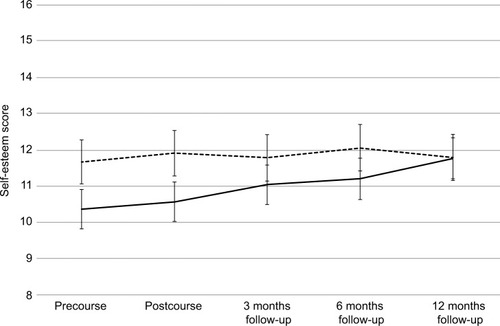

presents the predictors of self-esteem, positive affect, and negative affect for the whole sample. In the whole sample, being employed was associated with an increasing self-esteem trajectory. Overall, participants with COPD had higher scores on self-esteem than participants with morbid obesity. The statistically significant interaction effect between illness group and time indicated different self-esteem trajectories in the two illness groups. For the participants with morbid obesity, self-esteem increased linearly, and with a very large EF, across time (F=8.34, ES =5.71, P<0.01), whereas participants with COPD showed no change pattern ( and ).

Figure 1 Trajectories of self-esteem in persons with morbid obesity (n=139) and in persons with COPD (n=97).

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CI, confidence interval.

Table 2 Predictors of self-esteem, positive affect, and negative affect (n=236)

Positive and negative affect

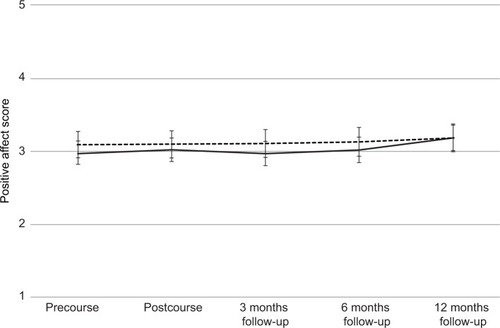

Over time, there were no statistically significant differences between the illness groups regarding positive affect. Similarly, there was no effect of time, and none of the sociodemographic variables showed any influence on the trajectory of positive affect ( and ).

Figure 2 Trajectories of positive affect in persons with morbid obesity (n=139) and in persons with COPD (n=97).

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CI, confidence interval.

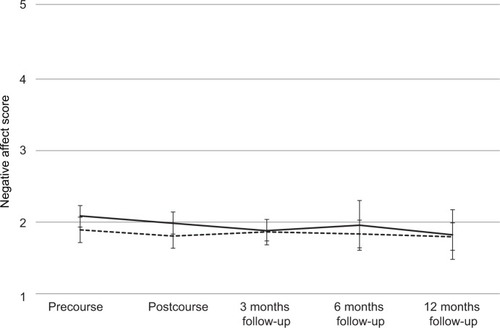

Concerning negative affect, there was no overall difference between the illness groups. Being employed was associated with a large ES (ES =3.02, P<0.01) and with a trajectory of reduced negative affect, as was higher age (ES =2.20, P<0.05). In both illness groups, negative affect was significantly reduced during the follow-up period (F=2.49, ES =1.09, P<0.05), with no difference in change pattern between the illness groups ( and ).

Figure 3 Trajectories of negative affect in persons with morbid obesity (n=139) and in persons with COPD (n=97).

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

The self-esteem trajectories were different for the participants in the two illness groups: for participants with morbid obesity, self-esteem increased across the 1-year follow-up period, whereas participants with COPD did not demonstrate change across time. For the total sample, the trajectory for positive affect was flat, but both groups showed a decrease in negative affect. Being employed was associated with increasing self-esteem in the total sample, and being employed and being of higher age was associated with decreasing negative affect.

Trajectories of self-esteem and positive and negative affect

Stigma is common in various groups with chronic illness.Citation24 In today’s Western culture, persons with morbid obesity are particularly prone to experience stigmatization, and experiences with stigma can decrease self-esteem.Citation25,Citation26 Thus, more stigma, and potentially more self-blame among persons with morbid obesity compared to persons with COPD, may contribute to explain differences regarding their initial self-esteem levels.Citation27

Previous studies have shown that persons with morbid obesity and persons with COPD had increased self-esteem and obtained positive changes in affect during relatively short follow-up periods.Citation5,Citation16 This study had a longer follow-up period than the cited studies, and it is promising to see that self-esteem in the participants with morbid obesity had a continuous increase during the 1-year follow-up. Research has argued the value of group work, particularly the sharing of experience and the social support inherent in such groups, for persons with morbid obesity who attend patient education courses.Citation28,Citation29 Thus, the longer lasting and largely group-based patient education programs may have initiated a positive course of self-esteem among these participants. The outcomes of changes in diet and activity during follow-up – ie, change in health, weight and body figure – may also be important contributors to the increased self-esteem in these participants.

Other explanations are similarly viable. For example, since the persons with morbid obesity had relatively low scores on self-esteem before they started the educational course, they may find it easier to increase their self-esteem (due to regression toward the mean) than participants with COPD, who had higher scores both at baseline and across all assessment points during the follow-up period. Furthermore, self-esteem theory and research suggests a relationship between high level of self-esteem and high stability of this self-evaluationCitation30 and between high self-esteem and high emotional stability as personality trait.Citation31 The participants with morbid obesity had lower levels of self-esteem, perhaps indicating that their self-esteem is less stable than for the participants with COPD, and thus, also more changeable for them. Among persons with morbid obesity, high interpersonal sensitivity and a tendency to overeat as a response to emotional difficulties may also be viewed as expressions of low emotional stability, as previously noted.Citation32 These aspects of the psychological profile associated with morbid obesity may all contribute to explain the different trajectories of self-esteem between the two illness groups.

For the participants with COPD, the trajectory of self-esteem was unchanged during the 1-year follow-up period. This result resembles this group’s trajectory of general self-efficacy as well as their trajectories of physical and mental health.Citation33,Citation34 Previous studies have also indicated relatively poor outcomes for persons with COPD, and particularly in a longer-term perspective.Citation35–Citation37 Compared to the participants with morbid obesity in the present study, the participants with COPD received patient education courses of shorter duration, consisting of fewer group sessions of discussion and sharing of experiences. Group discussion and feedback on personal experience are important aspects of patient education – thus, differences in course content and organization may contribute to explaining the results.Citation38 The prospects of health improvements because of treatment and/or lifestyle change are also worse for persons with COPD, compared to those with morbid obesity.

The two illnesses are markedly dissimilar in terms of their progression across time. Participants with COPD have to come to terms with a progressive disease for which there is no cure, whereas participants with morbid obesity can actively counter their health problem, not least by initiating and maintaining physical activity and an improved diet. In spite of the more positive self-esteem trajectory for the participants with morbid obesity compared to their COPD counterparts, we note that the two groups had about the same levels of self-esteem at the 1-year follow-up assessment (). This may indicate that those with the greatest need for an increase in self-esteem actually achieved it.

None of our participant groups achieved changes in positive affect across the 1-year period. The level of negative affect, however, decreased in both illness groups. This is in line with previous research, particularly for the participants with morbid obesity, as studies have found changes in affect to correspond with changes in self-esteem. For example, in a study of gastric bypass patients, increased self-esteem across a 6-month period was accompanied by a decrease in negative affect across the same period.Citation16 Similarly, in a mixed sample of persons with asthma and rheumatoid arthritis, Juth et alCitation9 found that lower self-esteem predicted lower positive and higher negative affect. For the COPD participants in our study, on the other hand, it appears that their experience of having less negative affect across time is unrelated to their self-esteem, as the latter did not change. Low negative affect has been described as a state of calmness and serenity,Citation2 and in a previous study with the COPD participants, we found that higher health-related quality of life 1 year after the patient education was associated with perceiving the illness to have a more chronic course.Citation19 If perceiving the illness as more chronic can be interpreted as being more reconciled with having the illness, then this may also contribute to explaining the decrease in negative affect among the participants with COPD. A state of reconciliation may also increase with higher age, a factor found to be associated with less negative affect in the whole sample.

We also note the positive impact from having work – in our study, being employed was related to increased self-esteem as well as to reduced negative affect. Employment provides a person not only with an income, but may also substantially strengthen his or her identity as a person of worth, a person who is capable, and a person needed by others. Previous studies have found paid work to be associated with better physical health in persons with COPD,Citation39,Citation40 suggesting that work might counteract a sedentary lifestyle in these persons, and by that contribute to better health.Citation40 Self-efficacy has been shown to be higher,Citation41 and its trajectories more positive,Citation33 among employed persons compared to persons who were not. However, it is likely that severity of illness may confound such associations – for those who are very ill, employment may be too stressful to be realistic. Nonetheless, our results do speak for the positive influence of work participation on affect and self-esteem, even in such different illness groups as morbid obesity and COPD.

Study limitations

The patient education courses for the obesity and COPD groups were largely equal in theoretical orientation, but the use of action plans and group sessions was more frequent in the obesity courses than in the COPD courses. The longer lasting courses for the obesity participants may have contributed to a more favorable trajectory of self-esteem in this group. The sample was one of convenience and relatively small. The lack of a control group and the inability to establish cause–effect relationships are limitations of the observational study design. A large number of statistical tests were performed, and due to the exploratory nature of the study, we retained the most common level of statistical significance. However, this may have caused us to report effects that were due to chance rather than to systematic differences (Type I error).

Conclusion and implications

Given the general risk of low self-esteem in persons with chronic illness,Citation8,Citation32,Citation42 health professionals should pay specific attention to this aspect when planning interventions. Our study indicates that increased self-esteem is achievable for persons with morbid obesity, and the patient education course received by the participants in this study appears to be promising. Given the stable, and generally higher, self-esteem among the participants with COPD, it is possible that low self-esteem is less of a problem in this illness group. Moreover, our study indicates that positive affect may be quite stable, but that negative affect may be reduced, in persons with these chronic illnesses. Higher age, and in particular being employed, were associated with the changes in the chosen outcomes. Future research may examine the role of personality, but also that of participation in important activities, for self-esteem and affect development in different illness groups.

Author contributions

The first author drafted the initial manuscript and contributed to the statistical analyses. The second author participated in designing the study. The third author performed the main statistical analysis. The fourth author was the principal investigator, was responsible for designing the study and for collecting the data. All authors participated in interpreting the data and drafting the final version of the manuscript, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the Norwegian Centre for Patient Education, Research and Service Development, Oslo, Norway. The contributions from the following Norwegian institutions are acknowledged: The Patient Education Centers at Oslo University Hospital – Aker, Oslo; Deacon’s Hospital, Oslo; Lovisenberg Diakonale Hospital, Oslo; Asker and Bærum Hospital, Sandvika; Østfold Hospital, Sarpsborg; and Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger. In addition, we acknowledge the contributions of the Pulmonary Rehabilitation Centers at Oslo University Hospital – Ullevål, Oslo; Krokeide Center, Nærland; and Glittreklinikken, Nittedal.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- World Health OrganizationInternational Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)Geneva, SwitzerlandWHO2001

- WatsonDClarkLATellegenADevelopment and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scalesJ Pers Soc Psychol1988546106310703397865

- RosenbergMConceiving the SelfNew York, NYBasic Books1979

- PinquartMSelf-esteem of children and adolescents with chronic illness: a meta-analysisChild Care Health Dev201239215316122712715

- NinotGMoullecGDesplanJPrefautCVarrayADaily functioning of dyspnea, self-esteem and physical self in patients with moderate COPD before, during and after a first inpatient rehabilitation programDisabil Rehabil200729221671167817852227

- AbilesVRodriguez-RuizSAbilesJPsychological characteristics of morbidly obese candidates for bariatric surgeryObes Surg201020216116718958537

- DavinSATaylorNMComprehensive review of obesity and psychological considerations for treatmentPsychol Health Med200914671672520183544

- HesselinkAEPenninxBWSchlosserMAThe role of coping resources and coping style in quality of life of patients with asthma or COPDQual Life Res200413250951815085923

- JuthVSmythJMSantuzziAMHow do you feel? Self-esteem predicts affect, stress, social interaction, and symptom severity during daily life in patients with chronic illnessJ Health Psychol200813788489418809639

- BisschopMIKriegsmanDMBeekmanATDeegDJChronic diseases and depression: the modifying role of psychosocial resourcesSoc Sci Med200459472173315177830

- SimpsonJLekwuwaGCrawfordTIllness beliefs and psychological outcome in people with Parkinson’s diseaseChronic Illn20139216517623585631

- GeyhSNickEStirnimannDSelf-efficacy and self-esteem as predictors of participation in spinal cord injury – an ICF-based studySpinal Cord201250969970622450885

- LuyckxKRassartJAujoulatIGoubertLWeetsISelf-esteem and illness self-concept in emerging adults with Type 1 diabetes: long-term associations with problem areas in diabetesJ Health Psychol201621454054924776688

- StrandEBZautraAJThoresenMØdegårdSUhligTFinsetAPositive affect as a factor of resilience in the pain – negative affect relationship in patients with rheumatoid arthritisJ Psychosom Res200660547748416650588

- LerdalAAndenaesRBjornsborgEPersonal factors associated with health-related quality of life in persons with morbid obesity on treatment waiting lists in NorwayQual Life Res20112081187119621336658

- MashebRMGriloCMBurke-MartindaleCHRothschildBSEvaluating oneself by shape and weight is not the same as being dissatisfied about shape and weight: a longitudinal examination in severely obese gastric bypass patientsInt J Eat Disord200639871672016868997

- World Health OrganizationGlobal Database on Body Mass Index Available from: http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jspAccessed March 18, 2010

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung DiseaseGlobal Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseGlobal Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease2011

- BonsaksenTHaukeland-ParkerSLerdalAFagermoenMSA 1-year follow-up study exploring the associations between perception of illness and health-related quality of life in persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis20149415024379660

- RosenbergMSociety and the Adolescent Self-imagePrinceton, NJPrinceton University Press1965

- YstgaardMVulnerable Adolescents and Social Support [Sårbar ungdom og sosial støtte]Rapport nr. 1/93Oslo, NorwayCentre for social networks and health1993

- TambsKModerate effects of hearing loss on mental health and subjective well-being: results from the Nord-Trondelag Hearing Loss StudyPsychosom Med200466577678215385706

- SPSS for Windows, version 220 [computer program]Armonk, NYIBM Corp2013

- EarnshawVAQuinnDMParkCLAnticipated stigma and quality of life among people living with chronic illnessesChronic Illn201182798822080524

- PuhlRBrownellKDBias, discrimination, and obesityObes Res200191278880511743063

- PuhlRMHeuerCAThe stigma of obesity: a review and updateObesity200917594196419165161

- BonsaksenTFagermoenMSLerdalAFactors associated with self-esteem in persons with morbid obesity and in persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cross-sectional studyPsychol Health Med201520443144225220791

- FagermoenMSBevanKBergACPersons with morbid obesity had increased self-efficacy and self-esteem after patient educationSykepleien Forskning201493216223

- BorgeLChristiansenBFagermoenMSMotivation for lifestyle changes among morbidly obese peopleSykepleien Forskning2012711422

- OwensTJStrykerSGoodmanNExtending Self-esteem Theory and ResearchCambridge, UKCambridge University Press2001

- RobinsRWTracyJLTrzesniewskiKPotterJGoslingSDPersonality correlates of self-esteemJ Res Pers2001354463482

- van HoutGCvan OudheusdenIvan HeckGLPsychological profile of the morbidly obeseObes Surg200414557958815186623

- BonsaksenTFagermoenMSLerdalATrajectories of self-efficacy in persons with chronic illness: an explorative longitudinal studyPsychol Health201429335036424219510

- BonsaksenTFagermoenMSLerdalATrajectories of physical and mental health among persons with morbid obesity and persons with COPD: a longitudinal comparative studyJ Multidiscip Healthc2016919120027175082

- HeppnerPSMorganCKaplanRMRiesALRegular walking and long-term maintenance of outcomes after pulmonary rehabilitationJ Cardiopulm Rehabil2006261445316617228

- RiesALKaplanRMMyersRPrewittLMMaintenance after pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic lung disease: a randomized trialAm J Respir Crit Care Med2003167688088812505859

- MoullecGLaurinCLavoieJMNinotGEffects of pulmonary rehabilitation on quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patientsCurr Opin Pulm Med2011172627121206273

- NossumRRiseMBSteinsbekkAPatient education – Which parts of the content predict impact on coping skills?Scand J Public Health201341442943523474954

- OrbonKHSchermerTRvan der GuldenJWEmployment status and quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseInt Arch Occup Environ Health200578646747415895242

- AndenæsRBentsenSBHvindenKFagermoenMSLerdalAThe relationships of self-efficacy, physical activity, and paidd work to health-related quality of life among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)J Multidiscip Healthc2014723924724944515

- LabriolaMLundTChristensenKBDoes self-efficacy predict return-to-work after sickness absence? A prospective study among 930 employees with sickness absence for three weeks or moreWork200729323323817942994

- DobbieMMellorDChronic illness and its impact: considerations for psychologistsPsychol Health Med200813558359018942011