Abstract

Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is caused due to intake of gluten, a protein component in wheat, barley, and rye. The only treatment currently available for CD is strict lifetime adherence to a gluten-free diet (GFD) which is a diet that excludes wheat, barley, and rye. There is limited information on barriers to following a GFD. The present study aimed to investigate the compliance with a GFD, barriers to compliance, and the impact of compliance on the quality of life (QOL) in Iranian children and adolescents suffering from CD.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, a total of 65 known cases of CD (both males and females), diagnosed in Namazi Hospital, a large referral center in south of Iran, selected by census were studied in 2014. Dietary compliance was assessed using a questionnaire. A disease-specific QOL questionnaire for children with CD (the celiac disease DUX [CDDUX]) was used. Comparisons between categorical variables were performed using chi-square test.

Results

Sixty-five patients, 38 females (58.5%) and 27 (41.5%) males, were surveyed. Mean (± standard deviation [SD]) age of the respondents was 11.3 (±3.8) years. Dietary compliance was reported by 35 (53.8%) patients. The mean (± SD) CDDUX score was higher in dietary-compliant patients (33.5 [±19.4] vs 26.7 [±13.6], respectively, P=0.23). The score of CDDUX in parents of patients in dietary-compliant group was more than the noncompliant patients (28.1 [±13.5] vs 22.1 [±14], respectively, P=0.1). Barriers to noncompliance were poor or unavailability (100%), high cost (96.9%), insufficient labeling (84.6%), poor palatability (76.9%), and no information (69.23%).

Conclusion

Approximately half of the patients with CD reported dietary compliance. Poor or unavailability was found to be the most important barrier contributing to noncompliance. The QOL was better in compliant patients. Proposed strategies to improve compliance are greater availability of gluten-free products, better food labeling, and better education about the diet and condition.

Introduction

Celiac disease (CD) is a condition of sensitivity to gluten, a protein component in wheat, barley, and rye.Citation1 Glutenin and gliadin are the main fractions of gluten which contribute to viscosity and elasticity properties of products.Citation2 The prevalence rate of CD is 1%–2%.Citation3 The minimum prevalence of gluten sensitivity among the Iranian population is from one out of 104 to one out of 166.Citation4,Citation5 CD can manifest with a range of clinical presentations, including chronic diarrhea, weight loss, and abdominal distention.Citation6 Because CD is often clinically silent, many patients remain undiagnosed and are at risk of complications, such as osteoporosis, infertility, or malignancy.Citation6 The burden caused by CD is high, and there is growing interest in the social dimensions of this condition.Citation6 The only treatment for CD is strict lifetime adherence to a gluten-free diet (GFD). In GFD, wheat, rye, and barley are eliminated, and therefore, many daily foods are avoided.Citation7 Treatment with a GFD results in improvement of many clinical and serological parameters,Citation8 decreasing the risk of malignancies,Citation9 and also prevents the development of autoimmune diseases such as diabetes mellitus (DM) type 1.Citation10 The limitations of the GFD compliance may also affect the quality of life (QOL) in children.Citation11 Only few studies have been published with regard to ability of children and adolescents to cope with GFD.Citation12 Some studies have reported that CD considerably affects lifestyle of children and their families.Citation13 There is limited information on barriers to following a GFD. Knowing factors that affect compliance would help to improve patient’s ability to maintain a strict GFD. The aim of this study was to investigate compliance with GFD, barriers to compliance, and the impact of compliance on the QOL in Iranian children and adolescents suffering from CD.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted with the approval of the ethics committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. Written informed consent was obtained from parents of all the participants. A total of 110 known cases of CD, diagnosed in Namazi Hospital, a large referral center in south of Iran, affiliated to Shiraz University of Medical Sciences in Shiraz, selected by census were studied in 2014. All of the patients were subjected to screening for CD using anti-tissue transglutaminase (anti-tTG) antibodies. Those positive for anti-tTG antibodies were subjected to endoscopy where mucosal details in the descending part of the duodenum were recorded, and biopsy was conducted. CD was diagnosed by compatible serologic tests (using serum endomysial [EMA] and anti-tTG antibodies), small bowel biopsy, and response to a GFD according to the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition criteria. Children with biopsy-confirmed CD diagnosed before the initiation of the study were included, whereas those aged <2 and >18 years, with incomplete medical record, and who were not interested in participating in the study were excluded. Finally, 65 patients (both males and females) were included in the study. Dietary compliance was assessed using a questionnaire and by the evaluation of the EMA and anti-tTG antibodies. Questions were addressed to parents and also their children. Compliance with the GFD was defined as subjects might have been unaware of eating any gluten. The compliance rate was evaluated in relation to sex, family history of CD, comorbidities, parental education, occupational status of parents, duration of disease, number of siblings, type of family (nuclear and joint), and QOL.

To assess the QOL, celiac disease DUX (CDDUX) questionnaire was used. The CDDUX consists of 12 items divided into three domains: diet (6), communication (3), and having CD (3). A five-point Likert scale based on a diagram with faces expressing different emotional states is used for the answers. There is also a version of questionnaire with the same questions for parents, about their children.Citation14 To assess the reliability of the questionnaires, a test–retest assessment (n=15) was made within 2-week interval.Citation15 Kappa statistic and percent agreement between responses (the proportion of participants grouped within the same response category for test and retest) were used to determine the repeatability of the categorical variables. All items assessed showed good agreement between test and retest (>80%). The data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables are presented as mean (± SD) or median (interquartile range), and discrete variables are presented as relative frequencies (%). Discrete variables were compared using chi-square test, and continuous variables were compared using t-test (and when the variables were not normally distributed, they were compared using Mann–Whitney test). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Sixty-five children, 38 females (58.5%) and 27 (41.5%) males, were surveyed. Mean (± SD) age of the respondents was 11.3 (±3.8) years. The mean (± SD) age at diagnosis was 8.11 (±4.2) years. The duration of their follow-up was in the range of 1–144 months. Patients were classified into two groups according to age: group A, <10 years (21 patients) and group B, 10–18 years (44 patients).

Twenty-seven (41.5%) patients before the diagnosis of CD presented with two or more symptoms, while 38 patients (58.5%) showed only one symptom. Ten (15.4%) children had a first-degree relative with biopsy-confirmed CD. Overall, growth failure and abdominal pain were commonly presented (70.8% and 63%, respectively). The most frequent comorbidity was DM type 1 (five patients). Other comorbidities, such as autoimmune thyroiditis, allergy, and anemia, were also seen. Most of the patients referred to the clinic due to growth failure and abdominal pain (24.6% and 15.4%, respectively). Eighty percent of patients reported weight gain following GFD. Fourteen (21.5%) patients were living in joint families. Approximately 17% of the mothers were working outside home.

Mean (± SD) total scores of CDDUX were calculated as 30 (±17) and 25 (±14) for children and their parents, respectively. Mean (± SD) total scores of CDDUX were higher in male patients in comparison to female patients (33.5 [±18.7] vs 27.9 [±15.7], P=0.25). Furthermore, mean (± SD) total scores of CDDUX in parents of male patients were significantly higher in comparison to parents of female patients (32.2 [±12.6] vs 20.1 [±13.6], P<0.001). The score of CDDUX in parents of patients was less than the patients (25.2 [±14.4] vs 30.2 [±15], respectively, P=0.009).

Among the 65 patients, 35 (53.8%) stated that they were not aware of taking any food containing gluten (compliant), and 46.2% said that they sometimes ate gluten-containing food (noncompliant). Of those eating food containing gluten, 30% stated that they did so more than twice a week, and the remainder, once or less than once a week. Almost 94% of children on a strict GFD were asymptomatic, although five (16.7%) of the complaints had positive EMA or anti-tTG antibodies. Among the 30 noncompliant children, 18 (60%) patients were symptomatic, and eight (29.6%) of them had positive EMA or anti-tTG antibodies. In total, seven (18.9%) out of the 37 asymptomatic children had positive EMA/tTG antibodies.

Although nonsignificant, there were higher noncompliance rates among female patients than males (52.6% vs 37%, P=0.2). The patients with a positive family history were more compliant (60%, P=0.3). Noncompliance was higher in joint than in nuclear families (57.1% vs 43.1%, P=0.4). Dietary compliance was better in patients with comorbidity (57.1%, P=0.7).

Compliance was better in patients belonging to families with less number of siblings (58.3% of the dietary-compliant patients had one or no sibling). None of the factors described were significantly correlated with compliance ().

Table 1 Demographic profile of patients with celiac disease

Mean (± SD) duration of disease of the patients in compliant and noncompliant groups was calculated as 3.7 (±3.4) and 2.6 (±3.1) years, respectively (P=0.2).

Mean (± SD) education years of mothers in compliant and noncompliant groups were 8.7 (±3.1) and 10.3 (±3), respectively (P=0.04). Mean (± SD) education years of fathers in compliant and noncompliant groups were 10 (±3.8) and 12.2 (±3.2), respectively (P=0.02).

The mean (± SD) CDDUX score was higher in dietary-compliant patients (33.5 [±19.4] vs 26.7 [±13.6], respectively, P=0.23). The score of CDDUX in parents of patients in dietary-compliant group was more than the noncompliant patients (28.1 [±13.5] vs 22.1 [±14], respectively, P=0.1).

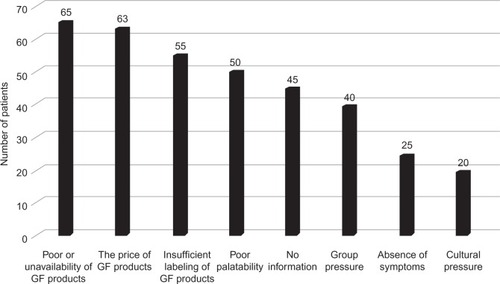

The barriers to dietary compliance reported by patients with CD are listed in . The main barriers to compliance reported by the patients were as follows: poor or unavailability, 65 (100%); high cost, 63 (96.9%); insufficient labeling, 55 (84.6%); poor palatability, 50 (76.9%); and no information, 45 (69.23%).

Figure 1 Barriers to dietary compliance reported by patients with celiac disease.

None of the participants were covered by health insurance for the cost of the gluten-free products (GFPs). After starting the GFD, 86.2% noted a significant improvement in their health.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the evaluation of the compliance of children, adolescents, and their parents with a GFD has not been reported previously in an Iranian population. Although diagnosis of CD is important, focusing on the patient’s ability to comply with a GFD is essential too. Eating is not just a physiological action but also related to socioemotional needs of people. If diet is limited, it affects all aspects of a person’s life.Citation16 Our results showed that the effect of a GFD was dramatic in most patients. Little information is available on the reasons for noncompliance, especially in children.Citation17 One study showed that the main cause of noncompliance was the restrictive nature of the GFD.Citation18

In the present study, dietary compliance rate was 53.8%. This rate in the other populations (including Middle East) has been reported to be 30%–95%.Citation4,Citation19–Citation22 However, because compliance was assessed by self-reporting, some degrees of overestimation is possible. The findings in the present study, in consistence with that of Roma et al,Citation23 showed that poor compliance was seen even when all patients had biopsy-confirmed CD.

Although noncompliance was more common in female patients (ie, 52.6%), similar to previous studies, the relationship between compliance and sex was not statistically significant.Citation24 Higher noncompliance rate in female patients may be explained by family pressure as they approach marriage age,Citation25 which is a social issue in Iranian and some other Asian cultures. Noncompliance was more common in female patients aged 10–18 years (ie, 56%) compared to females <10 years of age (ie, 46.2%).

The present study found a statistically nonsignificant decrease in compliance during 10–18 years of age. These results are similar to other studies.Citation25 Good compliance in young children could be due to parents’ awareness about the disease. However, children often do not comply with GFD during adolescence, and may stop their GFD.Citation25

This study also found parents’ education as a significant factor affecting the compliance. Chauhan et alCitation25 also showed that compliance is affected by maternal education. An explanation is that mothers are responsible for preparation of gluten-free (GF) foods, while fathers usually are responsible for paying for the household expenses and providing food items. So, in families in which father is more educated, there will be a better understanding of CD, and as a result, provision of GFPs may be easier.

In line with a previous study,Citation23 the compliance in children with positive family history of CD was better. Possible explanation could be more familiarity with the GFD in these patients.

Although results of the present study showed that compliance was lower in joint families and when numbers of siblings were more, in consistence with other studies, this relationship was not significant.Citation23,Citation25

Our study showed that 16.7% of the complaints had positive antibodies (EMA or anti-tTG). Among the 30 noncom-pliant children, 60% were symptomatic, whereas 29.6% of them had positive antibodies. Like a previous study,Citation26 these facts can indicate that unintentional GFD noncompliance is probable. An explanation is accidental consumption of gluten, when the labels on processed foods are inadequate or when gluten is present in meals prepared outside home.Citation27

Fourteen (21.5%) patients reported having other diseases. In this study, the most frequently related disorders were DM type 1 and autoimmune thyroiditis. Although compliance was more common in patients with comorbidity, as in other studies, there was no significant association between comorbidities and dietary adherence.Citation28

There are many barriers to GFD, which can affect QOL. In line with other studies,Citation17,Citation23,Citation25,Citation29 the main barriers include poor or unavailability, high cost, poor palatability, insufficient labeling, and no information. Availability of GF foods was, by far, the most important barrier to overall adherence, especially outside the home. Results of a cohort studyCitation29 had shown that the unavailability of GFD affects the compliance. GF foods are not freely available in Iran. In some cities, GFPs such as flour and biscuits are limitedly available from small-scale industries. Although most of them are made from GF cereals, cross-contamination of such cereals is a problem. Therefore, there is a serious need for large-scale industrial production of GFPs for CD patients in Iran.

Cost, taste, and labeling were also considerable barriers. The cost of GFPs is much higher than gluten-containing ones.Citation30 GFPs were, on average, 2.5 times more expensive than their gluten-containing counterparts.Citation30 The present study in line with other studies showed that noncompliance is more common when providing GFPs is considered a financial burden.Citation25 Because the GFD should be followed lifelong, the overall economic impact can be significant, especially if several persons in the household are suffering from CD. In Iran most GFPs are imported, and this has led to higher prices and intensified economic problems. Furthermore, the lack of insurance coverage of the cost of GFPs in our country is an obstacle to strict adherence to the GFD.

A problem in detecting food contamination with gluten was also noticed in Iran and other developing countries. Possible explanations may relate to the labeling itself and cross-contamination during the process of production and distribution of non-wheat products. The low compliance rate observed in the present study may be due to the limited participation of health care professionals in educating patients and their parents about GFD and food labeling. Due to the lack of gluten labeling on food items in Iran, it is difficult for a patient to know if a certain food product is GF or not. Patients and their parents require education about the disease, hidden gluten in foods, and adequate nutritional intake.Citation31

The CDDUX questionnaire was used to assess the QOL of patients. There is also a version of questionnaire with the same questions for parents. There is great value in having a parent proxy; this allowed better assessment of QOL, particularly due to a significant difference noted between responses of child and parent. Overall, children reported a better QOL than their parents (parents: 25.2 [±14.4] vs children: 30.2 [±15], P=0.009). This could be explained by the fact that the parents may think that their child has problems with the diet or that the child does not like the GF foods. The results of the present study, in consistence with other studies,Citation32,Citation33 showed that compliance with the GFD will result in a better QOL.

Our study had some limitations, including parental influence, possible selection bias due to the tertiary clinical setting, and a cross-sectional design, so our finding cannot be generalized to the general population of children and adolescents with CD in Iran, but further studies by other researchers in a more representative population of children and adolescents with CD will benefit.

Conclusion

Approximately half of the patients with CD reported dietary compliance. The main barriers include poor or unavailability, high cost, poor palatability, insufficient labeling, and no information. Adequate financial support by government and health insurers is needed. Proposed strategies to improve compliance and QOL are better food labeling, greater availability of GFPs in restaurants and food stores, and better education about the diet.

Acknowledgments

The present manuscript was extracted from a thesis written by Maryam Taghdir and financially supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (grant number 93-6980).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HillIDDirksMHLiptakGSGuideline for the diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease in children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and NutritionJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200540111915625418

- GujralHSRosellCMImprovement of the breadmaking quality of rice flour by glucose oxidaseFood Res Int20043717581

- RodrigoLCeliac diseaseWorld J Gastroenterol2006124165776584

- ShahbazkhaniBMalekzadehRSotoudehMHigh prevalence of coeliac disease in apparently healthy Iranian blood donorsEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200315547547812702902

- AkbariMRMohammadkhaniAFakheriHScreening of the adult population in Iran for coeliac disease: comparison of the tissue-transglutaminase antibody and anti-endomysial antibody testsEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol200618111181118617033439

- FasanoAClinical presentation of celiac disease in the pediatric populationGastroenterology20051284S68S7315825129

- VeenMte MolderHGremmenBvan WoerkumCQuitting is not an option: an analysis of online diet talk between celiac disease patientsHealth2010141234020051428

- ReillyNRAguilarKHassidBGCeliac disease in normal-weight and overweight children: clinical features and growth outcomes following a gluten-free dietJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr201153552853121670710

- SilanoMVoltaUDe VincenziADessìMDe VincenziMEffect of a gluten-free diet on the risk of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma in celiac diseaseDig Dis Sci200853497297617934841

- CosnesJCellierCViolaSIncidence of autoimmune diseases in celiac disease: protective effect of the gluten-free dietClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20086775375818255352

- HallertCGrännöCHultenSLiving with coeliac disease: controlled study of the burden of illnessScand J Gastroenterol2002371394211843033

- JadrešinOMišakZSanjaKSonickiZŽižicVCompliance with gluten-free diet in children with coeliac diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200847334434818728532

- Di FilippoTOrlandoMConcialdiGThe quality of life in developing age children with celiac diseaseMinerva Pediatr201365659960824217629

- van DoornRKWinklerLMZwindermanKHMearinMLKoopmanHMCDDUX: a disease-specific health-related quality-of-life questionnaire for children with celiac diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200847214715218664865

- StreinerDNormanGHealth Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use2nd edOxfordOxford University Press1995

- LeeANewmanJMCeliac diet: its impact on quality of lifeJ Am Diet Assoc2003103111533153514576723

- MacCullochKRashidMFactors affecting adherence to a gluten-free diet in children with celiac diseasePaediatr Child Health201419630530925332660

- GreenPHStavropoulosSNPanagiSGCharacteristics of adult celiac disease in the USA: results of a national surveyAm J Gastroenterol200196112613111197241

- UkkolaAMakiMKurppaKPatients’ experiences and perceptions of living with coeliac disease-implications for optimizing careJ Gastrointestin Liver Dis2012211172222457855

- HögbergLGrodzinskyEStenhammarLBetter dietary compliance in patients with coeliac disease diagnosed in early childhoodScand J Gastroenterol200338775175412889562

- FabianiETaccariLMRätschI-MDi GiuseppeSCoppaGVCatassiCCompliance with gluten-free diet in adolescents with screening-detected celiac disease: a 5-year follow-up studyJ Pediatr2000136684184310839888

- BaradaKBitarAMokademMA-RHashashJGGreenPCeliac disease in Middle Eastern and North African countries: a new burden?World J Gastroenterol201016121449145720333784

- RomaERoubaniAKoliaEPanayiotouJZellosASyriopoulouVDietary compliance and life style of children with coeliac diseaseJ Hum Nutr Diet201023217618220163513

- ErrichielloSEspositoODi MaseRCeliac disease: predictors of compliance with a gluten-free diet in adolescents and young adultsJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr2010501546019644397

- ChauhanJKumarPDuttaABasuSKumarAAssessment of dietary compliance to gluten free diet and psychosocial problems in Indian children with celiac diseaseIndian J Pediatr201077664965420532683

- MachadoJGandolfiLAlmeidaFAlmeidaLMZandonadiRPPratesiRGluten-free dietary compliance in Brazilian celiac patients: questionnaire versus serological testNutr Clin Diet Hosp20133324649

- KarajehMAHurlstoneDPPatelTMSandersDSChefs’ knowledge of coeliac disease (compared to the public): a questionnaire survey from the United KingdomClin Nutr200524220621015784479

- KurppaKLauronenOCollinPFactors associated with dietary adherence in celiac disease: a nationwide studyDigestion201286430931423095439

- ZarkadasMCranneyACaseSThe impact of a gluten-free diet on adults with coeliac disease: results of a national surveyJ Hum Nutr Diet2006191414916448474

- StevensLRashidMGluten-free and regular foods: a cost comparisonCan J Diet Pract Res200869314715018783640

- RajpootPSharmaAHarikrishnanSBaruahBJAhujaVMakhariaGKAdherence to gluten-free diet and barriers to adherence in patients with celiac diseaseIndian J Gastroenterol201534538038626576765

- WagnerGBergerGSinnreichUQuality of life in adolescents with treated coeliac disease: influence of compliance and age at diagnosisJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200847555556118955861

- PicoMSpiritoMRoizenM[Quality of life in children and adolescents with celiac disease: Argentinian version of the specific questionnaire CDDUX] Calidad de vida en niños y adolescentes con enfermedad celíaca: Versión argentina del cuestionario específico CDDUXActa Gastroenterol Latinoam20124211219 Spanish22616492